Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina

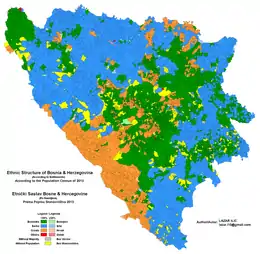

The Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Serbian: Срби у Босни и Херцеговини, romanized: Srbi u Bosni i Hercegovini) are one of the three constitutive nations (State-forming nations) of the country, predominantly residing in the political-territorial entity of Republika Srpska.

Serbian traditional clothing from (clockwise from top):

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,086,733 (2013)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Republika Srpska | 1,001,299 (81.5%) |

| Federation of B&H | 56,550 (2.4%) |

| Brčko District | 28,884 (34.6%) |

| Languages | |

| Serbian | |

| Religion | |

| Serbian Orthodox Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| South Slavs | |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

In the other entity, Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbs form the majority in Drvar, Glamoč, Bosansko Grahovo and Bosanski Petrovac. They are frequently referred to as Serbs (Serbian: Срби, romanized: Srbi) in English, regardless of whether they are from Bosnia or Herzegovina.

They are also known by regional names such as Krajišnici ("frontiersmen" of Bosanska Krajina), Semberci (Semberians), Bosanci (Bosnians), Birčani (Bircians), Romanijci (Romanijans), Posavci (Posavians), Hercegovci (Herzegovinians). Serbs have a long and continuous history of inhabiting the present-day territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and a long history of statehood in this territory.

From the 15th to the 19th century, Orthodox Serbs in modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina were often persecuted under the Ottoman Empire. In the 20th century, persecution by Austria-Hungary, WWII genocide, political turmoil and poor economic conditions caused more to emigrate. In the 1990s, many Serbs moved to Serbia proper and Montenegro.

Having lived throughout much of Bosnia-Herzegovina prior to the Bosnian War, the majority now live in the Republika Srpska. According to the report by the Bosnia and Herzegovina statistics office, on the census of 2013 there were 1,086,733 Serbs living in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[1]

History

Middle Ages

Serbs settled the Balkans in the 7th century, and according to De Administrando Imperio (ca. 960), they settled an area near Thessaloniki and from there they settled part of today's Bosnia and Herzegovina. They inhabited and ruled Serbia, which included "Bosnia" (with two inhabited cities; Kotor and Desnik), and "Rascia", and the maritime principalities of Travunija, Zahumlje and Paganija, the first two having been divided roughly at the Neretva river (including what is today Herzegovina). The population's Serbian ethnic identity remains a matter of dispute and some historians think that it rather indicates political situation at the time.[2][3][4]

Serbia was at the time ruled by the Vlastimirović dynasty. The progenitor, according to Porphyrogenitos, was the prince that led the Serbs to the Balkans during the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641)[5] The author gives the early genealogy: "As the Serb Prince who fled to Emperor Heraclius" in the time "when Bulgaria was under the Rhōmaíōn" (thus, before the establishment of Bulgaria in 680), "by succession, his son and later descendents of the family ruled as princes. After some years, Višeslav is born, and from him Radoslav, and from him Prosigoj, and from him Vlastimir."[5] The time and circumstances of the first three rulers are largely unknown. It is hypothesized that Višeslav ruled around 780, but it is unclear when Radoslav and Prosigoj would have ruled. When the Serbs were mentioned in 822 in the Royal Frankish Annals ("the Serbs, who control the greater part of Dalmatia"; ad Sorabos, quae natio magnam Dalmatiae partem obtinere dicitur) either Radoslav or Prosigoj ruled Serbia.[5] But according to John (Jr.) Fine, it was hard to find Serbs in this area since the Byzantine sources make no suggestion that they had settled here and they were limited to the southern coast, also it is possible that among other tribes exists tribe or group of small tribes of Serbs.[6]

During the rule of Mutimir (r. 851–891), the Serbs were Christianized. The Serbs were important Byzantine allies; the fleets of Zahumlje, Travunia and Konavli (Serbian "Pomorje") were sent to fight the Saracens who attacked the town of Ragusa (Dubrovnik) in 869, on the immediate request of Basil I, who was asked by the Ragusans for help.[7] The territory of Bosnia was ruled by several Serbian dynasties, almost in the entire continuity of the Middle Ages. Bosnia or most of its present-day areas were ruled by Vlastimirovic, Vojislavljevic, Nemanjic, and Kotromanic dynasties. Prince Petar (r. 892–917), defeated Tišemir in Bosnia, annexing the valley of Bosna.[8] Petar took over the Neretva, after which he seems to have come into conflict with Michael, a Bulgarian vassal ruling Zahumlje (with Travunia and Duklja).[9]

Dalmatia, in the antique period, stretched from modern-day Dalmatia far into the hinterland, northwards close to the Sava river, and eastwards to the Ibar river.[5] Višeslav's great-grandson Vlastimir began his rule around 830, and he is the oldest Serbian ruler of which substantial data exists. Vlastimir united the Serbian tribes in the vicinity[10][11] The Serbs were alarmed, and most likely consolidated due to the spreading of the Bulgarian Khanate towards their borders (a rapid conquest of neighbouring Slavs),[12][13] in self-defence,[12][14] and possibly sought to cut off the Bulgar expansion to the south (Macedonia).[11] After the victory over the Bulgars, Vlastimir's status rose,[14] and according to Jr. Fine, he went on to expand to the west, taking Bosnia, and Herzegovina (Zahumlje)[15]

Vlastimir married off his daughter to Krajina, the son of a local župan of Trebinje, Beloje, around 847–48.[16] With this marriage, Vlastimir elevated the title of Krajina to archon.[16] The Belojević family was entitled the rule of Travunija. Krajina had a son with Vlastimir's daughter, named Hvalimir, who would later on succeed as župan of Travunia.

Vlastimir's elevation of Krajina, the practical independence of Travunija, shows, according to Živković, that Vlastimir was a Christian who understood the monarchal ideology that developed in the early Middle Ages.[17]

Prince Časlav Klonimirović takes the throne in 927 (r. 927–960) with the death of the Bulgar Khan, and immediately puts himself under Byzantine overlordship. Eastern Christian (Orthodox) influence greatly increases and the two maintain close ties throughout his reign. He enlarged Serbia, incorporating Travunia and parts of Bosnia[18] while the borders of Caslav's state are unknown.[19] He took over regions previously held by Michael Višević, who disappears from sources in 925. Časlav managed to unite all mentioned Serb territories and established a state that encompassed the shores of the Adriatic Sea, the Sava river and the Morava valley as well as today's northern Albania according to the DAI. Časlav defeated the Magyars on the Drina river banks when protecting Bosnia,[20] however, he was later captured and drowned in the Sava. After his death, Duklja emerged as the most powerful Serb polity, ruled by the Vojislavljević dynasty. Bosnia was under Serbian rule on several occasions, especially in the middle of the 10th and the end of the 11th century, but according to Noel Malcolm it would be wrong to conclude that Bosnia was ever a "part of Serbia" because Serbian kingdoms which also included Bosnia, at that time did not include most of today's Serbia.[21]

Five decades later, Jovan Vladimir emerged as the Prince of Serbs, ruling as a Bulgarian vassal from his seat at Bar. A possible descendant, Stefan Vojislav,[22] led numerous revolts in the 1030s against the Byzantine Emperor (the overlord of the Serbian lands), successfully becoming independent by 1042. His realm included all lands earlier held by Časlav Klonimirović, and he would be eponymous to the second Serbian dynasty, the Vojislavljevići, who were based in Duklja. The latter may possibly be a branch of the Vlastimirović dynasty. A cadet branch of the Vojislavljević dynasty, the Vukanovići, emerged as the third dynasty in the 1090s. It was named for Grand Prince Vukan, who held Rascia (the hinterland) under his cousin, King of Duklja Constantine Bodin (ca. 1080–1090) in the beginning, but denounced any overlordship in 1091 when he had raided much of the Byzantine towns of Kosovo and Macedonia.

The Nemanjić dynasty, the most powerful dynasty of Serbia, is founded with the emergence of Stefan Nemanja,[23] also a descendant of the same line.

Constantin Bodin, who ruled from 1080 to 1101, fought Byzantium and the Normans further to the south, and took the town of Dyrrachium. He established vassal states in Bosnia (under Stefan) and Raška (under Vukan and Marko), which recognized his supremacy. Vukan and Marko, the new princes of Raška were probably sons of the aforementioned Petrislav. Vukan (1083–1115) was the Grand Župan while Marko headed administration of a part of the land. The Byzantine Emperor Alexios later forced Vukan to acknowledge Byzantine suzerainty in 1094.

Nemanjic dynasty "for the most part, ruled mainly Herzegovina, and occasionally all parts of Bosnia, and the regions of Podrinje, Srebrenica, Posavina, Usora and Soli Stefan Dragutin (Serbian: Стефан Драгутин; died 12 March 1316) was the King of Serbia from 1276–82 and King of Syrmia (Srem) from 1282 to 1316. He ruled Serbia which included large parts of present-day Bosnia, until his abdication in 1282, when he became ill. He continued to rule the royal domains of Syrmia as King of Syrmia, and his younger brother succeeded him as ruler of Serbia. Later he became a monk and changed his name to Teokist.

In the list of Serbian saints, Stefan Dragutin is venerated on either 12 November or 30 October (Old Style and New Style dates). The first Serbian Emperor also temporarily conquered most of Bosnia and included it into his Empire.

The Kotromanić (Vuk's Cyrillic: Котроманић, pl. Kotromanići/Котроманићи) were members of late medieval Bosnian noble and later royal dynasties. Rising to power in the middle of the 13th century as bans of Bosnia, with control over little more than the valley of the eponymous river, the Kotromanić rulers expanded their realm through a series of conquests to include nearly all of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, large parts of modern-day Croatia and parts of modern-day Serbia and Montenegro, with Tvrtko Ieventually establishing the Kingdom of Bosnia in 1377. The Kotromanić intermarried with several southeastern and central European royal houses. The last sovereign, Stephen Tomašević, ruled briefly as Despot of Serbia in 1459 and as King of Bosnia between 1461–63, before losing both countries – and his head – to the Ottoman Turks.

Ottoman rule

Bosnian Serbs often rebelled against Ottoman rule. The Serb Uprising of 1596–97 was suppressed at Gacko. It was a part of a broader Serb struggle against the Ottomans, in support of Austria and Venice.

In 1809, Jančić's Revolt broke out in Gradiška. This revolt was a part of the Serbian Revolution, and an attempt of Serb rebels in Bosnia to connect with Serbian rebels in the Sanjak of Smederevo, and an offensive into Bosnia they initiated.

In 1834, Priest Jovica's Revolt broke out in Gradiška. In 1858, Pecija's First Revolt broke out in Knešpolje.

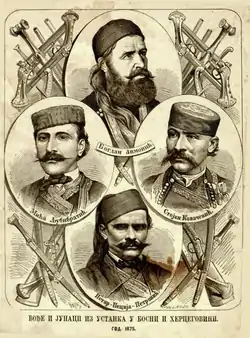

From 1815 to 1878 Ottoman authority in Bosnia and Herzegovina decreased. After the reorganization of the Ottoman army and abolition of the Jannisaries, Bosnian nobility revolted, led by Husein Gradaščević, who wanted to establish autonomy in Bosnia and Herzegovina and to stop any further social reforms. During the 19th Century, various reforms were made in order to increase freedom of religion which sharpened relations between of Catholics and Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Soon, economic decay would happen and nationalist influence from Europe came to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Since the state administration was disorganized and national consciousnesses was strong among the Christian population, the Ottoman Empire lost control over Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Serbian population in Herzegovina revolted, which led to the Herzegovina Uprising. The Ottoman authorities were unable to defeat the rebels, so Serb Principalities Serbia and Montenegro took advantage of this weakness and attacked the Ottoman Empire in 1876, soon after the Russian Empire did the same. The Turks lost the war in 1878. After the Congress of Berlin was held in same year, mandate of Bosnia and Herzegovina was transferred to the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

More specifically, In 1875, the Herzegovina Uprising broke out in the Bosnia Vilayet. On July 2, 1876, Golub Babić and his 71 commanders signed the "Proclamation of the Unification of Bosnia with Serbia". This event is often known, among Serbian historians, as the "Third Serbian Uprising". This rebellion directly led to independence of Serb principalities of Motenegro and Serbia. It lasted from 1875 up to Austro-Hungarian occupation in 1878. In 1876, during this "Third Serbian Uprising" in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1875–1878), Bosnia and Herzegovina, and its Serbian people's leadership proclaimed union and annexation to Serbia("Proclamation of the Unification of Bosnia with Serbia"), under its Kniaz (Prince) Milan IV Obrenovich. The Turks lost the war in 1878. After the Congress of Berlin was held in same year, Bosnia and Herzegovina was transferred to the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[24]

Around one quarter of rebel leaders (voivodes) of the Serbian Revolution were born in modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina or had their roots in the region of Bosnia or Herzegovina.[25] Mateja Nenadović met with local Serb leaders from Sarajevo in 1803 in order to negotiate their part in the rebellion, with the ultimate goal being that the two armies meet in Sarajevo.[25]

During the various Balkan liberation wars (Serbian Revolution 1804–1830, Balkan Wars 1875–1878, or Balkan Wars 1912–1913 etc.) Muslim populace from all over the Balkans gradually settled the last pockets of Ottoman rule in the Balkans, one of which is Bosnia.[26]

Austro-Hungarian rule

In 1878, Bosnia and Herzegovina became a protectorate of Austria-Hungary, which the Serbs strongly opposed, even launching guerrilla operations against Austro-Hungarian forces. Even after the fall of the Ottoman rule, the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina was divided. Serbian politicians in the Kingdom of Serbia and the Principality of Montenegro sought to annex Bosnia & Herzegovina into a unified Serbian state and that aspiration often caused political tension with Austria-Hungary. Another ambition of Serbian politicians was to incorporate the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina into the Kingdom of Serbia. The Habsburg Governor Béni Kállay resorted to co-opt religious institutions. Soon, the Austrian Emperor gained support to name Orthodox metropolitans and Catholic bishops and to choose Muslim hierarchy.

At the time, Bosnia and Herzegovina was facing a Habsburg attempt at modernization. The majority were Serbs, while Muslims and Croats were a minority, and in even smaller percentages Slovenes, Czechs and others. During this period, the most significant event is Bosnian entry to European political life and the shaping of ethnic Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina into a modern nation. At the end of the 19th century, Bosnian Serbs founded various reading, cultural and singing societies, and at the beginning of the 20th century, a new Bosnian Serb intelligentsia played a major role in the political life of Serbs. One of the major Serbian cultural and national organizations was Prosvjeta, Bosanska Vila and Zora, among others. Serbian national organizations were focused on the preservation of Serbian language, history and culture. First Serbian Sokol societies on the present territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina were founded in the late 19th century by intellectuals. Stevan Žakula, is remembered as a prominent worker in opening and maintaining sokol and gymnastic clubs. Žakula was the initiator of the establishment of Serbian gymnastics society "Obilić" in Mostar and Sports and gymnastic society "Serbian soko" in Tuzla. Sokol societies were also established in another cities across the Bosnia and Herzegovina.[27]

In 1908, Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia & Herzegovina, at this time majority Serb-inhabited, going against the directions of the Berlin Congress, which caused an uproar in Montenegro and Serbia. This Annexation crisis, was one of the reasons for later tensions which led to the eruption of WWI.

The first parliamentary elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina were held in 1910, the winner was Serbian National Organization. On June 28, 1914, Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip made international headlines after assassinating Arch Duke Francis Ferdinand in Sarajevo. This sparked World War I leading to Austria-Hungary's defeat and the incorporation of Bosnia and Herzegovina into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

World War I

During WWI, Serbs in Bosnia were often blamed for the outbreak of the war, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and were subjected to persecution by the Austro-Hungarian authorities, including internment and looting of their businesses, by people who were instigated to ethnic violence.[28]

Bosnian and Herzegovinian Serbs served in Montenegrin and Serbian army en masse, as they felt loyalty to the overall pan-Serbian cause. Bosnian Serbs also served in Austrian Army, and were loyal to Austria-Hungary when it came to Italian Front, but they often deserted and switched sides when they were sent to the Russian front, or to Serbian Front. Many Serbs supported the advance of fellow Montenegrin Serb Army, when it entered into Herzegovina, and advanced close to Sarajevo in 1914, as the King of Montenegro, King Nicholas I Petrovich-Njegos was very popular among Bosnian and Herzegovinian Serbs because of his pan-Serbian and Serbian nationalist views and help during Herzegovinian uprisings in the 19th century.

Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

After World War I, Bosnia and Herzegovina became part of the internationally unrecognized State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs which existed between October and December 1918. In December 1918, this state united with the Kingdom of Serbia (in its 1918 borders[29]), as Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes,which was renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. Even with around 45% Serbs living in Bosnia and Herzegovina, far more than any other group within Bosnia, Serbian leadership of the state decided to acknowledge demands of Muslim representative Mehmed Spaho, and respect the pre-war territorial integrity of Bosnia & Herzegovina, therefore not changing internal district borders of Bosnia.[30] Bosnian Serbs constituted around half of the total Bosnian population, but they constituted a vast territorial majority and have unilaterally proclaimed union with Serbia, for the second time in modern history, now in 1918. In total, 42 out of 54 municipalities in Bosnia & Herzegovina proclaimed union(annexation to) Serbia, without the approval of „People's Yugoslav“ government in Sarajevo, without even consulting them, in 1918. The regime of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was characterized by limited parliamentarism, and ethnic tensions, mainly between Croats and Serbs. The state of the Kingdom became dire and King Alexander was forced to declare a dictatorship on 6 January 1929. The Kingdom was renamed into Yugoslavia, divided into new territorial entities called Banovinas. Yugoslavia was preoccupied with political struggles, which led to the collapse of the state after Dušan Simović organized a coup in March 1941 and after which Nazi Germany invaded Yugoslavia.

King Alexander was killed in 1934, which led to the end of dictatorship. In 1939, faced with killings, corruption scandals, violence and the failure of centralized policy, the Serbian leadership agreed a compromise with Croats. Banovinas would later, in 1939, evolve into the final proposal for the partition of the joint state into three parts or three Banovinas, one Slovene Banovina, one Croatian and one Serbian, with each encompassing most of the ethnic space of each ethnic group. Most of the territory of contemporary Bosnia and Herzegovina was to be part of the Banovina Serbia, since most of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina was majority Serb-inhabited, and the Serbs constituted overall relative majority. On 24 August 1939, the president of the Croatian Peasant Party, Vladko Maček and Dragiša Cvetković made an agreement (Cvetković-Maček agreement) according to which Banovina of Croatia was created with many concessions on the Serbian side. Serbs in Dalmatia, Slavonia, Krajina and Posavina found themselves in a Croatian entity within Yugoslavia, while virtually no Croats remained in the Serbian federal entity in 1939.

Most Bosnian Serbs supported federalist policies of Pribicevic during the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

World War II

During World War II, Bosnian Serbs were put under the rule of the fascist Ustashe regime in the Independent State of Croatia. Under Ustashe rule, Serbs along with Jews and Roma people, were subjected to systematic genocide.[31] Serbs in villages in the countryside were hacked to death with various tools, thrown alive into pits and ravines or in some cases locked in churches that were afterwards set on fire.[32] Others were sent to concentration camps.[33] The Kruščica concentration camp, located near the town of Vitez, was one of the concentration camps established by Ustashe; it was founded in April 1941 for Serb and Jewish women and children.[34][35] According to the US Holocaust Museum, 320,000–340,000 Serbs were murdered under Ustasha rule.[36] In an interview on 4 November 2015, Bakir Izetbegović, Bosniak Member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, affirmed the persecutions of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia as genocide.[37]

Serbs suffered a drastic demographic shift during WWII due to their persecution. The official brutal policies of the Independent State of Croatia, involving expulsion, murder and forced conversion to Catholicism of Orthodox Serbs,[38] contributed that Serbs never recover within Bosnia & Herzegovina. The Federal Bureau of Statistics in Belgrade composed a figure of 179,173 persons killed in the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Second World War: 129,114 Serbs (72.1%); 29,539 Muslims (16.5%); 7,850 Croats (4.4%); others (7%). By the plans of Nazi Germany and the Independent State of Croatia 110,000 Serbs were relocated and transported to German-occupied Serbia. Just in the period of May to August 1941 over 100,000 Serbs were expelled to Serbia. In the heat of war Serbia had 200,000–400,000 Serbian refugees from Ustaša-held Bosnia and Herzegovina. By the end of war 137,000 Serbs have permanently left the territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The May 1941 Sanski Most revolt against the Ustashe was suppressed in two days. In June 1941, Serbs in eastern Herzegovina rebelled against the authorities of the Independent State of Croatia, following massacres against the majority Serb population. Serb rebels, under the leadership of both local Serbs Montenegrins, attacked police, gendarmerie, Ustashe and Croatian Home Guard forces in the region. The rebellion was suppressed after two weeks. The Serbs of Bosnia were mainly involved in one of two factions in World War II: the Chetniks or the Yugoslav Partisans.

Most of the anti-fascist combat and battles were fought in mainly Serb-inhabited areas of Bosnia & Herzegovina, such as the Battle of Neretva, Battle of Sutjeska, Drvar Operation and Kozara Battle.

During the entire course of the WWII in Yugoslavia, according to the records of recipients of Partisan pensions, 64.1% of all Bosnian Partisans were Serbs.[39][40][41]

Between 1945 and 1948, following World War II, approximately 70,000 Serbs migrated from the People's Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina to Vojvodina after the Germans had left, which was a part of Communist policy.

Communist Yugoslavia

During the communist era, Bosnia and Herzegovina were populated by three ethnic groups: the Croats, the Serbs and the Muslims (later re-designated as Bosniaks). Many Serbs declared their nationality as Yugoslav and like all ethnic groups at the time, Serbs collaborated and were friends with their fellow citizens, whilst also maintaining their culture, primarily through their following of Serbian Orthodox Church. Many Serb scholars were subjected to persecution and false accusations of irridentism.

Demographics

The 2013 population census registered 1,086,733 Serbs or 30.8% of the total population of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosnian Serbs are the most territorially widespread nation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The vast majority i.e. 1,001,299 live on the territory of the Republika Srpska, where they constitute 81.5% of population. Bosnian Serbs are adherents of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Serbs form a demographic majority in these municipalities: Banja Luka, Bijeljina, Prijedor, Doboj, Zvornik, Gradiška, Teslić, Prnjavor, Laktaši, Trebinje, Derventa, Novi Grad, Modriča, Kozarska Dubica, Pale, Foča, Drvar, Glamoč, Bosansko Grahovo and Bosanski Petrovac. Serbs are also a relative minority in Brčko.

Demographic history

| Ethnic totals and percentages | |||||||||||||

| Year/Population | Serbs | % | Total BiH Population | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1879 | 496,485 | 42.88% | 1,158,440 | ||||||||||

| 1885 | 571,250 | 42.76% | 1,336,091 | ||||||||||

| 1895 | 673,246 | 42.94% | 1,568,092 | ||||||||||

| 1910 | 825,418 | 43.49% | 1,898,044 | ||||||||||

| 1921 | 829,290 | 43.87% | 1,890,440 | ||||||||||

| 1931 | 1,028,139 | 44.25% | 2,323,555 | ||||||||||

| 1948 | 1,136,116 | 44.29% | 2,565,277 | ||||||||||

| 1953 | 1,261,405 | 44.40% | 2,847,459 | ||||||||||

| 1961 | 1,406,057 | 42.89% | 3,277,935 | ||||||||||

| 1971 | 1,393,148 | 37.19% | 3,746,111 | ||||||||||

| 1981 | 1.320.644 | 32,02 % | 4,124.008 | ||||||||||

| 1991 | 1,369,258 | 31.21% | 4,364,649 | ||||||||||

| 2013 | 1,086,733 | 30.78% | 3,551,159 | ||||||||||

| Official Population Census Results - note: some Serbs declared themselves as Yugoslavs in some censuses | |||||||||||||

Medieval Bosnia and Ottoman Empire

There were no reliable population censuses in the Middle Ages, however most of the medieval sources concerning the identity and the demographics of medieval Bosnia state that the area was continuously inhabited mainly by Serbs,[42] who were either Orthodox by faith or followers of an Orthodox sect of Bogomil. Heading 32 of De Administrando Imperio of Constantine Porphyrogenitus, is called "On the Serbs and the lands in which they live". It speaks of the territories inhabited by Serbs in which he mentions Bosnia, specifically two inhabited cities, Kotor and Desnik, both of which are in an unidentified geographic position.[43][42]

Austria-Hungary and Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Kingdom of Yugoslavia)

Austria-Hungary pursued a demographic policy of reducing the Serbian population and trying to erase their identity, converting it to a "Bosnian nationhood", therefore, Austrian population census only had religious affiliation as a main determinism of identity. In the last Austrian census of 1910, there were 825,418 Orthodox Serbs, which constituted 43.49% of the total population. The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1917, states: "According to the census of 22 April 1895, Bosnia has 1,361,868 inhabitants and Herzegovina 229,168, giving a total population of 1,591,036. The number of persons to the square mile is small (about 80), less than that in any of the other Austrian crown provinces excepting Salzburg (about 70). This average does not vary much in the six districts (five in Bosnia, one in Herzegovina). The number of persons to the square mile in these districts is as follows: Doljna Tuzla, 106; Banjaluka, 96; Bihac, 91; Serajevo, 73, Mostar(Herzegovina), 65, Travnik, 62. There are 5,388 settlements, of which only 11 have more than 5,000 inhabitants, while 4,689 contain less 500 persons. Excluding some 30,000 Albanians living in the south-east, the Jews who emigrated in earlier times from Spain, a few Osmanli Turks, the merchants, officials. and Austrian troops, the rest of the population (about 98 per cent) belong to the southern Slavonic people, the Serbs. Although one in race, the people form in religious beliefs three sharply separated divhe Mohammedans, about 550,000 persons (35 per cent), Greek Schismatics, about 674,000 persons (43 per cent), and Catholics, about 334,000 persons (21.3 per cent). The last mentioned are chiefly peasants."[44]

World War II

Serbs suffered large negative (decreasing) demographic shift during WWII. The official policies of the Independent State of Croatia, involving expulsion, murder and forced conversion of Serbs,[38] contributed that Serbs never recover demographically within Bosnia & Herzegovina. The Federal Bureau of Statistics in Belgrade composed a figure of 179,173 persons killed in the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Second World War: 129,114 Serbs (72.1%); 29,539 Muslims (16.5%); 7,850 Croats (4.4%); others (7%). By the plans of Nazi Germany and the Independent State of Croatia 110,000 Serbs were relocated and transported to German-occupied Serbia. Just in the period of May to August 1941 over 100,000 Serbs were expelled to Serbia. In the heat of war Serbia had 200,000-400,000 Serbian refugees from Ustaša-held Bosnia and Herzegovina. By the end of war 137,000 Serbs have permanently left the territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Communist Yugoslavia

Communist authorities implemented a policy of silent "demographic emptying" of Serbs from Bosnia, by dividing Serbs into several republics, causing a "brain drain" of Serbs from Bosnia to Serbia. Also, the communist policies of rapid urbanization and industrialization, devastated the traditional rural life of Serbs, causing drastic halt in natural growth of Serbs. The first Yugoslav census recorded a decreasing number of Serbs; from the first census in 1948 to the last one from 1991, the percentage of Serbs decreased from 44.3% to 31.2%,[45] even though the total number increased. According to the 1953 census, Serbs were in the majority in 74% of the territory of Bosnia & Herzegovina, and according to the census of 2013, Serbs are the majority on over 50% of Bosnia & Herzegovina. Their total number in 1953 was 1,261,405, that is 44.3% of total Bosnian population.[46] According to the 1961 census, Serbs made up 42.9% of total population, and their number was 1,406,057.[46] After that, districts were divided into smaller municipalities.

According to the 1971 census, Serbs were 37.2% of total population, and their number was 1,393,148.[47] According to the 1981 census, Serbs made up 32.02% of total population, and their number was 1,320,644.[47] After 1981, their percentage continued to reduce. From 1971 to 1991, the percentage of Serbs fell due to emigration into Montenegro, Serbia, and Western Europe. According to the 1991 census, Serbs were 31.21% of the total population, and their number was 1,369,258.[47]

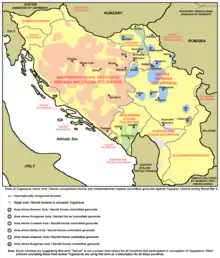

Bosnian War

The total number of Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina continued to reduce, especially after the Bosnian War broke out in 1992. Soon, an exodus of Bosnian Serbs occurred when a large number of Serbs were expelled from central Bosnia, Ozren, Sarajevo, Western Herzegovina and Krajina. According to the 1996 census, made by UNHCR and unrecognized by Sarajevo, there was 3,919,953 inhabitants, of which 1,484,530 (37.9%) were Serbs.[48] In the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the percentage of Serbs slightly changed, although, their total number reduced.

Politics

State level

Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as other two constitutive nations, have their representative in the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Presidency has three members, one Bosniak, one Croat and one Serb. The Bosniak and the Croat are elected in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, while the Serb is elected in the Republika Srpska. The current president of the Republika Srpska is Željka Cvijanović.

The current Serb member of the Presidency is Milorad Dodik of the SNSD.

The Parliamentary Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina has two chambers, House of Representatives and House of Peoples. House of Peoples has 15 members, five Bosniaks, five Croats and five Serbs. Bosniak and Croat members of the House of Peoples are elected in the Parliament of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, while five Serb members are elected in the National Assembly of Republika Srpska. The 42 members of the House of Representatives are elected directly by voters, two-thirds are from the Federation while one-third is from the Republika Srpska.[49]

Federal level

According to its constitution, Republika Srpska has its own president, people's assembly (the 83-member unicameral People's Assembly of Republika Srpska), executive government (with a prime minister and several ministries), its own police force, supreme court and lower courts, customs service (under the state-level customs service), and a postal service. It also has its symbols, including coat of arms, flag (a variant of the Serbian flag without the coat of arms displayed) and entity anthem. The Constitutional Law on Coat of Arms and Anthem of the Republika Srpska was ruled not in concordance with the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina as it states that those symbols "represent statehood of the Republika Srpska" and are used "in accordance with moral norms of the Serb people". According to the Constitutional Court's decision, the Law was to be corrected by September 2006. Republika Srpska later changed its emblem.

Although the constitution names Sarajevo as the capital of Republika Srpska, the northwestern city of Banja Luka is the headquarters of most of the institutions of government, including the parliament, and is therefore the de facto capital. After the war, Republika Srpska retained its army, but in August 2005, the parliament consented to transfer control of Army of Republika Srpska to a state-level ministry and abolish the entity's defense ministry and army by 1 January 2006. These reforms were required by NATO as a precondition of Bosnia and Herzegovina's admission to the Partnership for Peace programme. Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the programme in December 2006.[50]

Political parties

Currently, there are several Serbian political parties in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Republic of Srpska. The Serbian Democratic Party (SDS), the Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD), and Party of Democratic Progress (PDP) are the most popular parties.

SDS was founded in 1990 and is major political parties among Bosnian Serbs, being the most powerful during the Bosnian Civil War (1992–1995). SNSD was founded on pro-European, democratic, federalist, socialist principles, but has later on switched its tendencies into populism and pro-Russian external policies. PDP is Christian democratic, traditionalist, conservative and pro-Europeanist political party.

Culture

Cultural and education society, Prosvjeta was founded in Sarajevo in 1902. It quickly became the most important organization gathering ethnic Serb citizens. In 1903 was founded Gajret, Serbian Muslim Cultural Society. Academy of Sciences and Arts of the Republika Srpska is active since 1996.

Architecture and art

Bosnia and Herzegovina is rich in Serbian architecture, especially when it comes to numerous Serbian churches and monasteries. Modern Serbo-Byzantine architectural style which started in the second half of the 19th century is not only present in the sacral but also in civil architecture. Churches and monasteries are decorated with frescoes and iconostasis. Museum of Old Orthodox Church in Sarajevo is among the five in the world by its rich treasury of icons and other objects dating from different centuries.[51]

Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina have made a significant contribution to modern Serbian painting. Notable painters include Miloš Bajić, Jovan Bijelić, Špiro Bocarić, Vera Božičković Popović, Stojan Ćelić, Vojo Dimitrijević, Lazar Drljača, Oste Erceg, Nedeljko Gvozdenović, Kosta Hakman, Momo Kapor, Ratko Lalić, Đoko Mazalić, Svetislav Mandić, Radenko Mišević, Roman Petrović, Ljubomir Popović, Pero Popović, Branko Radulović, Svetozar Samurović, Branko Šotra, Todor Švrakić, Mica Todorović, Milovan Vidak, Rista Vukanović. In 1907 P. Popović, Radulović and Švrakić exhibited in one of the two exhibitions that year that marked the beginnings of the modern painting tradition in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Among the sculptors prominent is Sreten Stojanović.

Ozren Monastery

Ozren Monastery.jpg.webp) Interior of Old Orthodox Church in Sarajevo

Interior of Old Orthodox Church in Sarajevo Inside of Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, Banja Luka

Inside of Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, Banja Luka

Language and literature

The Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina speak the Eastern Herzegovinian dialect of Serbian language for which is characteristic ijekavian pronunciation.

Traces of Serbian language on this territory are very old which prove old inscriptions such as Grdeša's tombstone, the oldest known stećak. One of the most important Serbian manuscripts Miroslav Gospel, was written for the Serbian Grand Prince Miroslav of Hum. Serbian language is rich with several medieval gospels written in Bosnia and Herzegovina. They are decorated with miniatures.

In the early 16th century Božidar Goraždanin founded Goražde printing house. It was one of the earliest printing houses among the Serbs, and the first in the territory of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. Goražde Psalter printed there is counted among the better accomplishments of early Serb printers.

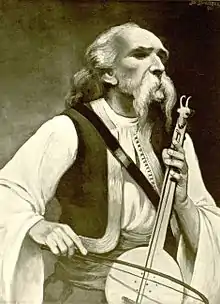

Bosnian Serbs gave significant contribution to the Serbian epic poetry. Famous singers of the epic poetry are Filip Višnjić and Tešan Podrugović.

The works of Serbian writers from Bosnia and Herzegovina are of great importance to the entire Serbian literature. Notable authors include Ivo Andrić, Branko Ćopić, Meša Selimović, Svetozar Ćorović, Petar Kočić, Sima Milutinović Sarajlija, Borivoje Jevtić, Jovan Palavestra, Jovan Kršić, Gavro Vučković Krajišnik, Aleksa Šantić, Jovan Dučić, Jovan Sundečić, Marko Vranješević, Mladen Oljača, Risto Trifković, Risto Tošović, Skender Kulenović, Duško Trifunović, Vojislav Lubarda, Radoslav Bratić, Momo Kapor, Vladimir Kecmanović, Vule Žurić, Vladimir Pištalo ...

Bosanska vila from Sarajevo and Zora from Mostar founded in the 19th century are important literary magazines.

Music

Music of Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina include traditional instruments such as gusle, frula, gajde, tamburica, etc. First Serbian singing societies in Bosnia and Herzegovina were set up in Foča (1885), Tuzla (1886), Prijedor (1887), Mostar and Sarajevo (1888) and other cities across the country.[52] First concert in Bosnia and Herzegovina was held in Banja Luka in 1881.[53]

Serbian music is rich in folk songs of Serbian people in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Many songs are performed in traditional way of singing called ojkanje. Serbian singers and composers such as Rade Jovanović, Jovica Petković, Dragiša Nedović and others gave significant contribution to special type of songs called sevdalinka. Aleksa Šantić's poem Emina became one of the most known sevdalinkas. Notable performers of folk music include Vuka Šeherović, Nada Mamula, Nedeljko Bilkić, Nada Obrić, Marinko Rokvić, etc.

Bosnian and Heregovians Serbs largely participated in Yugoslav pop-rock scene that was active since the end of the World War II until the break up of the country. Serbian musicians are members, and often leaders of popular bands such as Ambasadori, Bijelo Dugme, Bombaj Štampa, Indexi, Plavi orkestar, ProArte, Regina, Vatreni Poljubac, Zabranjeno pušenje. Zdravko Čolić is one of the biggest Yugoslav and Serbian music stars. Among singer-songwriters significant career made Jadranka Stojaković, Srđan Marjanović.

Post Yugoslav popular music singers include Željko Samardžić, Romana, Nedeljko Bajić Baja, Saša and Dejan Matić.

Dušan Šestić composed national anthem of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Theatre and cinema

The first theatre show in Bosnia and Herzegovina was organized by Serb Stevo Petranović in Tešanj in 1865 while the first shows in Sarajevo were organized in the house of Serb Despić family.[54] The first feature film in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Major Bauk was directed by Nikola Popović by the script of Branko Ćopić. Significant directors include Emir Kusturica, double winner of the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, Zdravko Šotra, Nebojša Komadina, Predrag Golubović, Boro Drašković, Gorčin Stojanović, Radivoje Andrić, Ognjenka Milićević, Miroslav Belović, Dejan Mijač, Egon Savin... Among the sreenwriters prominent are Gordan Mihić, Ranko Božić, Srđan Koljević... Actors that achieved success in Yugoslav and Serbian cinematography include Predrag Tasovac, Branko Pleša, Marko Todorović, Tomo Kuruzović, Tamara Miletić, Slobodan Đurić, Slobodan Ćustić, Tihomir Stanić, Nikola Pejaković, Nebojša Glogovac, Davor Dujmović, Nataša Ninković, Danina Jeftić, Brankica Sebastijanović...

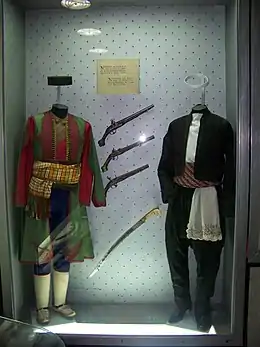

Folklore

Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina gave significant contribution to the folklore of Serbian people, including folk costume, music, traditional singing and instruments, epic poetry, crafts, and dances. The dresses of Bosnia are divided into two groups; the Dinaric and Pannonian styles. In Eastern Herzegovina, the folk costumes are closely related to those of Old Herzegovina. Cultural and artistic societies across the country practice folklore tradition.

Dresses from East Herzegovina (left) and urban Bosnia (right) 1875.

Dresses from East Herzegovina (left) and urban Bosnia (right) 1875. Zmijanje embroidery, UNESCO World Cultural heritage

Zmijanje embroidery, UNESCO World Cultural heritage

Education

The first education institutions of Bosnian Serbs were monasteries, of which the most significant were Dobrun, Klisina, Krupa on Vrbas, Liplje, Mostanica, Ozren, Tavna, Tvrdos, Gracanica of Herzegovina, Stuplje, Donja Bisnja, among many others throughout Bosnia & Herzegovina. The most significant people workingfor the elementary education of Bosnian Serbs in the 19th century were Jovan Ducic, Petar Kocic, and Aleksa Santic, among others, who founded and organized elementary schools throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina. Staka Skenderova established Sarajevo's first school for girls on 19 October 1858. The educational system in Ottoman era and Austro-Hungarian occupation was based on strict negation and suppression of Serbian identity. The educational system of Bosnia and Herzegovina during communism was based on a mixture of nationalities and the suppression of Serb identity. With the foundation of Serb Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, later simply called Serb Republic, Bosnian Serb schools took the educational system from Serbia.

At the same time, University of Sarajevo, split into two, one Muslim in Western Sarajevo, and one Serbian, renamed University of East Sarajevo, with official Serbian language, the latter having most of the pre-war professors and lecturers. There is also Serbian University in Banja Luka, called University of Banja Luka. After signing the Dayton accords, jurisdiction over education in Republika Srpska was given to RS Government, while in Federation, jurisdiction over education was given to the cantons. Municipalities with Serb majority or significant minority, schools with Serbian language as official one also exist. Another education institutes are Agricultural Institute of Republic of Srpska - Banja Luka, Scientific Research Institute of University of Banjaluka, Institute of Genetic Resources in Banja Luka, Serbian Lexicographic Institute of Bosnia and Herzegovina, research Institute for Materials and Constructions of Serb Republic and Institute for Education in Banja Luka.

Religion

Right: Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Banja Luka

The Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina are predominantly Eastern Orthodox Christians, belonging to the Serbian Orthodox Church. Serbian Orthodox Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina is organized in five subdivisions, one metropolitanate (Dabar and Bosnia), and four eparchies (Bihać and Petrovac, Banja Luka, Zvornik and Tuzla, and Zahumlje and Herzegovina). Eparchy of Zahumlje and Herzegovina, earlier The Metropolitanate of Zahumlje was founded in 1219, by Archbishop Sava, the same year the Serbian Orthodox Church acquired its autocephaly status from Constantinople. Thus, it was one of the original Serbian Orthodox bishoprics.

Bosnian Serb Makarije Sokolović was the first patriarch of the restored Serbian Patriarchate, after its lapse in 1463 that resulted from the Ottoman conquest of Serbia. He is celebrated as saint. Several Bosnian Serbs are beatified in Serbian Orthodox church of which one of the most famous is Basil of Ostrog. In the 16th century, altrought Ottoman law prohibited the bilding of new churches several Orthodox monasteries were built (in Tavna, Lomnica, Paprača, Ozren and Gostović), while Rmanj monastery in northwestern Bosnia was first mentioned in 1515. According to Noel Malcolm Orthodox believers were oppressed and humiliated, but it can be concluded that Ottoman regime favored the Orthodox Church.[55]

The first Serbian high school opened in Bosnia and Herzegovina was Sarajevo orthodox seminary in 1882. On the grounds of this seminary was founded the Theological Faculty in Foča, as part of the University of East Sarajevo. Between 1866 and 1878 in Banja Luka worked theological school, while nowadays is active theological school in Foča.

There are many Serbian churches and monasteries across the Bosnia and Herzegovina hailing from different periods. Each subdivision has its cathedral church and bishop's palace.

Sport

Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina have contributed significantly to the Yugoslav and Serbian sport.

First Serbian Sokol societies on the present territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina were founded in the late 19th century by intellectuals. Stevan Žakula, Croatian Serb, is remembered as a prominent worker in opening and maintaining sokol and gymnastic clubs. Žakula was the initiator of the establishment of Serbian gymnastics society "Obilić" in Mostar and Sports and gymnastic society "Serbian soko" in Tuzla. Sokol societies were also established in another cities across the Bosnia and Herzegovina.[27]

Football is the most popular sport among the Bosnian Serbs. The oldest Serb dominated Club in Bosnia and Herzegovina is Slavija Istočno Sarajevo, founded in 1908, while one of the most popular is Borac Banja Luka winner of Mitropa Cup and Yugoslav Cup. Serbian clubs participate in Premier League of Bosnia and Herzegovina and First League of the Republika Srpska which is run by Football Association of Republika Srpska. Notable players that represented Yugoslavia, Serbia and Bosnia include Branko Stanković, Milan Galić, Velimir Sombolac, Dušan Bajević, Boško Antić, Ilija Pantelić, Miloš Šestić, Savo Milošević, Mladen Krstajić, Neven Subotić, Zvjezdan Misimović, Luka Jović, Sergej Milinković-Savić, Ognjen Vranješ, Gojko Cimirot, Srđan Grahovac, Nemanja Bilbija, Dario Đumić, Zoran Kvržić, Mijat Gaćinović, Rade Krunić ... etc. Zvjezdan Misimović served as captain of the Bosnia and Herzegovina national team from 2007 to 2012 while Ljupko Petrović led Red Star Belgrade to the Champions League trophy in 1991. Marko Marin is a German player of Serbian ethnicity. Cican Stanković is an Austrian player of Serbian ethnicity.

The second most popular sport among Bosnian Serbs is basketball. Aleksandar Nikolić, is often referred to as, The Father of Yugoslav Basketball. He was voted two times European Coach of the Year winning three Euroleagues and two times FIBA Intercontinental Cup. Second of four fathers of Yugoslav basketball is Borislav Stanković, former general secretatary of FIBA and IOC member. Some of the players that successfully competed at the biggest world competitions are Ratko Radovanović, Dražen Dalipagić, Zoran Savić, Predrag Danilović, Vladimir Radmanović, Jelica Komnenović, Slađana Golić, Saša Čađo, Ognjen Kuzmić... KK Igokea currently plays in regional ABA League.

Handball club Borac Banja Luka is the most successful Serbian handball club in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It won EHF Champions League in 1976 and was runner up in 1975. Svetlana Kitić was voted the best female handball player ever by the International Handball Federation. Other accomplished players include Dejan Malinović, Milorad Karalić, Nebojša Popović, Zlatan Arnautović, Radmila Drljača, Vesna Radović, Nebojša Golić, Mladen Bojinović, Danijel Šarić...

The most famous Serbian volleyball family, Grbić family, hails from Trebinje in Eastern Herzegovina. Father Miloš was the captain of the team that won first Yugoslav medal at European championship while sons Vanja and Nikola became Olympic champions with Serbian team. Other players that represented Serbia with success are Đorđe Đurić, Brankica Mihajlović, Tijana Bošković, Jelena Blagojević, Sanja and Saša Starović. Mitar Djuric is a Greek male volleyball player of Serbian ethnicity.

Besides team sports, Bosnian Serbs achieved success and in individual sports such as Slobodan and Tadija Kačar in boxing, Radomir Kovačević, Nemanja Majdov and Aleksandar Kukolj in judo, Milenko Zorić in canoeing, Velimir Stjepanović and Mihajlo Čeprkalo in swimming, Andrea Arsović in shooting, etc.

Notable people

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  | .JPG.webp) |  | .jpg.webp) |  | |

|  |  |  | .JPG.webp) |  |  |  |  |  |  |

References

- Sarajevo, juni 2016. CENZUS OF POPULATION, HOUSEHOLDS AND DWELLINGS IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, 2013 FINAL RESULTS (PDF). BHAS. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- Živković, Tibor (2012). De conversione Croatorum et Serborum: A Lost Source. Belgrade: The Institute of History. pp. 161–162, 181–196.

- Budak, Neven (1994). Prva stoljeća Hrvatske (PDF). Zagreb: Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada. pp. 58–61. ISBN 953-169-032-4.

Glavnu poteškoću uočavanju etničke raznolikosti Slavena duž jadranske obale činilo je tumačenje Konstantina Porfirogeneta, po kojemu su Neretvani (Pagani), Zahumljani, Travunjani i Konavljani porijeklom Srbi. Pri tome je car dosljedno izostavljao Dukljane iz ove srpske zajednice naroda. Čini se, međutim, očitim da car ne želi govoriti ο stvarnoj etničkoj povezanosti, već da su mu pred očima politički odnosi u trenutku kada je pisao djelo, odnosno iz vremena kada su za nj prikupljani podaci u Dalmaciji. Opis se svakako odnosi na vrijeme kada je srpski knez Časlav proširio svoju vlast i na susjedne sklavinije, pored navedenih još i na Bosnu. Zajedno sa širenjem političke prevlasti, širilo se i etničko ime, što u potpunosti odgovara našim predodžbama ο podudarnosti etničkog i političkog nazivlja. Upravo zbog toga car ne ubraja Dukljane u Srbe, niti se srpsko ime u Duklji/Zeti udomaćilo prije 12. stoljeća. Povjesničari koji su bez imalo zadrške Dukljane pripisivali Srbima, pozivali su se na Konstantina, mada im on nije za takve teze davao baš nikakve argumente, navodeći Dukljane isključivo pod njihovim vlastitim etnonimom.

- Ćirković, Sima (2008). Srbi među europskim narodima (PDF). Golden marketing-Tehnička knjiga. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-9-53212-338-8.

- Ivić et. al 1987, pg. 21.

- Fine 2005, p. 35.

- "Vladimir Corovic: Istorija srpskog naroda". Rastko.rs. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Fine 1991, p. 148.

- Fine 1991, p. 149.

- Fine 1991, p. 141.

- Runciman 1930, ch. 2, n. 88.

- Bury 2008, pg. 372.

- Fine 1991, pp. 108-110.

- Ćorović 2001, ch. 2, III.

- Fine 1991, p. 110.

- Živković 2006, pg. 17.

- Živković 2006, pg. 18.

- Alexis P. Vlasto; (1970) The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs p. 209; Cambridge University, ISBN 0521074592

- Fine 1991, p. 160.

- Kostelski, Z. (1952). The Yugoslavs: The History of the Yugoslavs and Their States to the Creation of Yugoslavia. Philosophical Library. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-80220-886-6.

Presently the Magyars invaded Bosnia (945). Caslav now helped the Bosnians and they defeated the Magyar leader Kish in the battle at Cvilina on the river Drina..

- Malcolm 1995, p. 10-11.

- Fine 1991, p. 203.

- Casiday, Augustine (2012). The Orthodox Christian World. Routledge. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-13631-484-1.

- Herb & Kaplan 2008, p. 1529.

- Bataković, Dušan T. (2018). Zlatna nit postojanja. Belgrade: Catena Mundi. p. 142.

- İçduygu, Ahmet; Sert, Deniz (2015). Migration in the Southern Balkans. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. pp. 85–104. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-13719-3_5. ISBN 9783319137186.

- Savez Soko Srbije Archived 2016-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Bennett, Christopher (1997). Yugoslavia's Bloody Collapse: Causes, Course and Consequences. New York University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-81471-288-7.

In the aftermath of Franz Ferdinand's assassination, anti-Serb sentiment ran high throughout the Habsburg empire and in Croatia and in Bosnia-Herzegovina, it boiled over into anti-Serb pogroms. Though these pogroms were clearly incited by the Habsburg authorities..

- "Wikimedia Commons". Commons.wikimedia.org. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "Političko predstavljanje BiH u Kraljevini Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca / Kraljevini Jugoslaviji (1918.–1941.)". Parlament.ba. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- Byford, Jovan (2020). Picturing Genocide in the Independent State of Croatia: Atrocity Images and the Contested Memory of the Second World War in the Balkans. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-350-01598-2.

- Yeomans, Rory (2012). Visions of Annihilation: The Ustasha Regime and the Cultural Politics of Fascism, 1941-1945. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0822977933.

- Ross, Jeffrey Ian (2015). Religion and Violence: An Encyclopedia of Faith and Conflict from Antiquity to the Present. Routledge. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-31746-109-8.

- Avramov, Smilja (1992). Genocid u Jugoslaviji u svetlosti međunarodnog prava. Politika. p. 371. ISBN 9788676070664.

- Bauer, Yehuda (1981). American Jewry and the Holocaust: The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, 1939-1945. Wayne State University Press. p. 280. ISBN 0-8143-1672-7.

- US Holocaust Museum, ushmm. "Jasenovac". US Holocaust Museum.

- "Bio sam razočaran što Vučić ne prihvata sudske presude". N1.

- "Independent State of Croatia" (PDF). Yad Vashem World Holocaust and Research Documentation Center.

- Marko Attila Hoare. "The Great Serbian threat, ZAVNOBiH and Muslim Bosniak entry into the People's Liberation Movement" (PDF). anubih.ba. Posebna izdanja ANUBiH. p. 123. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Lenard J Cohen, Paul V Warwick (1983) Political Cohesion In A Fragile Mosaic: The Yugoslav Experience p. 64; Avalon Publishing, the University of Michigan; ISBN 0865319677

- Marko Attila Hoare (2002). "Whose is the partisan movement? Serbs, Croats and the legacy of a shared resistance" p. 4; The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. Informa UK Limited 15 (4);

- "Serbs, Bosnia and national identity". cafehome.tripod.com. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- De Administrando Imperio by Constantine Porphyrogenitus, edited by Gy. Moravcsik and translated by R. J. H. Jenkins, Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Washington D. C., 1993

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Bosnia and Herzegovina". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

- Bougarel, Xavier (2017). Islam and Nationhood in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Surviving Empires. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 76, 82. ISBN 978-1-35000-360-6.

- Bieber, Florian (2005). Post-War Bosnia: Ethnicity, Inequality and Public Sector Governance. Springer. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-23050-137-9.

- Ramet, Sabrina P.; Valenta, Marko (2016). Ethnic Minorities and Politics in Post-Socialist Southeastern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-10715-912-9.

- Robbers 2006, p. 117.

- "NATO - Topic: Signatures of Partnership for Peace Framework Document (country, name & date)". Archived from the original on 2012-03-11.

- "Magacinportal.org". Magacinportal.org. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- "Muzički život Srba u Bosni i Hercegovini (1881—1914)". Riznicasrpska.net. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- "O kulturnom i društvenom životu stare Banje Luke (5)". Glassrpske.com. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "The Legacy of the Despić Family". Sarajevo.travel. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Malcolm 1996, pp. 92-95.

Sources

- Primary sources

- Кунчер, Драгана (2009). Gesta Regum Sclavorum. 1. Београд-Никшић: Историјски институт, Манастир Острог.

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 9780884020219.

- Pertz, Georg Heinrich, ed. (1845). Einhardi Annales. Hanover.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter, ed. (1970). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472061860.

- Шишић, Фердо, ed. (1928). Летопис Попа Дукљанина (Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja). Београд-Загреб: Српска краљевска академија.

- Живковић, Тибор (2009). Gesta Regum Sclavorum. 2. Београд-Никшић: Историјски институт, Манастир Острог.

- Secondary sources

- Bataković, Dušan T. (1996). The Serbs of Bosnia & Herzegovina: History and Politics. Paris: Dialogue. ISBN 9782911527104.

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe. Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Ćorović, Vladimir. Crna knjiga: patnje Srba Bosne i Hercegovine za vreme svetskog rata 1914–1918. Jugoslovenski dosije, 1989.

- Cvijić, Jovan (1908). Анексија Босне и Херцеговине и српски проблем. Државна штампарија.

- Đukanović, Dragan. "Položaj Srba u postjugoslovenskim državama." Nova srpska politička misao 15.3+ 4 (2007): 367–379.

- Fine, John V. A. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-47208-149-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (2005). When Ethnicity did not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- McCormick, Rob (2008). "The United States' Response to Genocide in the Independent State of Croatia, 1941–1945". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 3 (1): 75–98.

- Mileusnić, Slobodan (1997). Spiritual Genocide: A survey of destroyed, damaged and desecrated churches, monasteries and other church buildings during the war 1991-1995 (1997). Belgrade: Museum of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Nilević, Boris (1990). Srpska pravoslavna crkva u Bosni i Hercegovini do obnove Pećke patrijaršije 1557. godine. Veselin Masleša.

- Papić, Mitar (1978). Istorija srpskih škola u Bosni i Hercegovini. Veselin Masleša.

- Pejanović, Mirko (1999). Bosansko pitanje i Srbi u Bosni i Hercegovini. Bosanska knjiga.

- Petranović, Bogoljub, and Novak Kilibarda. Srpske narodne pjesme iz Bosne i Hercegovine: Junačke pjesme starijeg vremena. Svjetlost, 1870.

- Radić, Radmila (1998). "Serbian Orthodox Church and the War in Bosnia and Herzegovina". Religion and the War in Bosnia. Atlanta: Scholars Press. pp. 160–182. ISBN 9780788504280.

- Dikica Stanisavljević (2006). Svedočenja o stradanju Srba iz Bosne i Hrvatske. Vardenik. ISBN 978-86-84487-04-1.

- Malcolm, Noel (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-81475-561-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

Quotations related to Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina at Wikiquote Media related to Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina at Wikimedia Commons

%252C_137v.jpg.webp)