Serbs of Romania

The Serbs of Romania (Romanian: Sârbii din România, Serbian: Срби у Румунији/Srbi u Rumuniji) are a recognized ethnic minority numbering 18,076 people (0.1%) according to the 2011 census. The community is concentrated in western Romania, in the Romanian part of the Banat region (divided with Serbia), where they constitute absolute majority in two communes and relative majority in one other.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 18,076 (2011)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Banat | |

| Languages | |

| Serbian and Romanian | |

| Religion | |

| Serbian Orthodox Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Croats of Romania |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

History

Historical background

Slavic presence is attested in Romania since the Early Middle Ages. The Avar Khaganate was the dominant power of the Carpathian Basin between around 567 and 803.[2] Most historians agree that Slavs and Bulgars, together with the remnants of the Avars, and possibly with Vlachs (or Romanians), inhabited the Banat region after the fall of the khaganate.[3] Place names of Slavic origin recorded already in the Middle Ages show the early presence of a Slavic-speaking population.[4]

Early modern period

From the late 14th- to the beginning of the 16th century a large number of Serbs lived in Wallachia and Moldavia.[5] Following Ottoman expansion in the 15th century, Serb mass migrations ensued into Pannonia.[5] Serbian Orthodox monasteries began to be built in the area from the 15th century, including Kusić and Senđurađ built by despot Jovan Branković, and in the 16th century including Bezdin and Hodoš built by the Jakšić family.[5] In the Ottoman period, some thirty Serbian Orthodox monasteries were built in the territory of Romania.[5]

Ottoman pressure traditionally forced members of several South Slavic communities to seek refuge in Wallachia - although under Ottoman rule as well, the latter was always subject to less requirements than regions to south of the Danube.

The Serbian Uprising in Banat (1594) included territories that are part of modern Romania. There were reprisals, contemporary sources speaking of "the living envied the dead".[6] After the crushing of the uprising in Banat, many Serbs migrated to Transylvania under the leadership of Bishop Teodor; the territory towards Ineu and Teiuș was settled, where Serbs had lived since earlier – the Serbs had their eparchies, opened schools, founded churches and printing houses.[6]

Serbs-proper probably constituted the vast majority of mercenary troops known as seimeni, given that their nucleus is attested to have been formed by "Serb seimeni" (as it was during their revolt in 1655), and that the rule of Prince Matei Basarab had witnessed the arrival of a large group of Serb refugees.

The Great Migrations of the Serbs in 1690 and 1737–39 led to additional settlement of Serbs.

Modern

These groups are, however, hard to distinguish one from another in early Wallachian references, as the term "Serbs" is regularly applied to all Southern Slavs, no matter where they might have originated. This only changed in the 19th century, through a transition made clear by an official statistic of 1830, which reads "census of how many Serbs are resident here in the town of Ploiești, all of them Bulgarians" (Giurescu, p. 269).

The Bărăgan deportations (1951–56) saw minorities (including Serbs) from the Banat region bordering Yugoslavia deported to south-eastern Romania due to the deteriorating Yugoslav–USSR relations and the perceived "elements who present a danger through their presence in the area" to the Romanian Communist regime.[7]

Demographics

According to the 2011 census, there was 18,076 people of the Serb minority,[1] down from 22,561 people in 2002.

In Caraș-Severin County, the Serbs constitute an absolute majority in the commune of Pojejena (52.09%)[8] and a plurality in the commune of Socol (49.54%).[9] Serbs also constitute absolute majority in the municipality of Svinița (87.27%) in the Mehedinți County.[10] The region where these three municipalities are located is known as Clisura Dunării in Romanian or Banatska Klisura (Банатска Клисура) in Serbian.

Localities

The following localities had a Serb population greater than 1% according to the 2011 census. Serbian placenames are included in brackets.

- Arad County

- Caraș-Severin County

- Mehedinți County

- Svinița (Свињица/Svinjica) — 90.27%

- Timiș County

- Beregsaul mic (Serbian: Nemet) — 50%

- Cenei (Serbian: Ченеј) — 16.1%

- Peciu Nou (Serbian: Улбеч) — 13.52%

- Sânpetru Mare (Serbian: Велики Семпетар) — 12.71%

- Variaș (Serbian: Варјаш) — 9.61%

- Saravale (Serbian: Саравола) — 7.38%

- Giulvăz (Serbian: Ђулвез) — 6.44%

- Cenad (Serbian: Чанад) — 6.39%

- Foeni (Фењ/Fenj) — 5.87%

- Topolovățu Mare (Serbian: Велики Тополовац) — 5.43%

- Giera (Serbian: Ђир) — 4.51%

- Recaș (Serbian: Рекаш) — 4.27%

- Denta (Дента/Denta) — 4.25%

- Deta (Дета/Deta) — 3.96%

- Birda — 3.46%

- Sânnicolau Mare (Serbian: Велики Семиклуш) — 2.98%

- Checea (Serbian: Кеча) — 2.82%

- Parța (Serbian: Парац) — 2.02%

- Săcălaz (Секелаз/Sekelaz) — 1.98%

- Becicherecu Mic (Serbian: Мали Бечкерек) — 1.78%

- Brestovăț (Брестовац/Brestovac) — 1.63%

- Timișoara (Serbian: Темишвар) — 1.52%

- Moravița (Моравица/Moravica) — 1.35%

Communes with a Serbian majority in Romania (2002 census)

Communes with a Serbian majority in Romania (2002 census).png.webp) Distribution of Serbs in Romania (2002 census)

Distribution of Serbs in Romania (2002 census)

Culture

Most of the Serbs in Romania are Orthodox Christians; the vast majority belong to Serbian Orthodox Church Eparchy of Timișoara.

List of Serbian Orthodox monasteries in Romania:

- Sveti Đurađ monastery (Манастир светог Ђорђа - Манастир свети Ђурађ / Manastir svetog Đorđa - Manastir sveti Đurađ). According to the legend, it was founded in 1485 by the Serbian despot, Jovan Branković. It was rebuilt in the 18th century.

- Šemljug monastery (Манастир Шемљуг / Manastir Šemljug). It was founded in the 15th century.

- Sveti Simeon monastery (Манастир светог Симеона / Manastir svetog Simeona).

- Bazjaš monastery (Манастир Базјаш / Manastir Bazjaš), built 1225

- Bezdin monastery (Манастир Бездин / Manastir Bezdin).

- Zlatica monastery (Манастир Златица / Manastir Zlatica).

- Kusić monastery (Манастир Кусић / Manastir Kusić).

- The "St. Peter and Paul" Serbian Church, raised in 1698-1702 in Arad, early Baroque architecture

Notable people

- Milica Despina of Wallachia (c. 1485 – d. 1554), Princess consort of Wallachia, regent of Wallachia from 1521 to 1522.

- Jovan Nenad (?–1527), Hungarian general and self-proclaimed "emperor", born in Lipova (northern Banat).

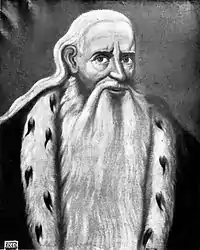

- Đorđe Branković (1645–1711), Transylvanian count, born in Ineu.

- Sava II Branković, Orthodox priest and Saint

- Jovan Tekelija (1660s — 1721 or 1722), nobleman and military officer, born in Arad.

- Peter Tekelija (1720–1792), Russian general-in-chief, born in Arad.

- Dimitrie Eustatievici (1730 - 1796), Imperial Austrian philologist, scholar and pedagogue, born in Grid.

- Dositej Obradović (1742–1811), Serbian writer and translator, born in Ciacova (Čakovo).

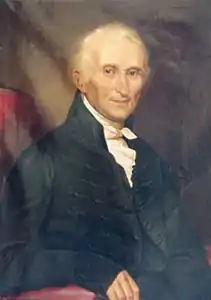

- Sava Tekelija (1761–1842), doctor of law, born in Arad.

- Konstantin Danil (1798-1873), Serbian painter, born in Lugoj.

- Aleksa Janković (1806-1869), Prime Minister of Serbia, born in Timișoara.

- Danilo Stefanović (1815-1886), Prime Minister of Serbia, born in Timișoara.

- Pavel Petrović (1818–1887), painter

- Ion Ivanovici (1845–1902) Romanian military band leader and composer.

- Alexandru Macedonski (1854–1920), Romanian poet, novelist, and literary critic, paternal Serb descent.[11]

- Stevan Aleksic (1876–1923), Serbian painter, born in Arad.

- Jovan Hadži (1884-1972), zoologist, born in Timișoara.

- Ivan Tabaković (1898–1977), Yugoslav painter, born in Arad.

- Emil Petrovici (1899–1968), Romanian linguist, born in Serbia.

- Slavomir Gvozdenovici or Gvozdenović (b. 1953), writer and the founder of the Union of Serbs of Romania.

- Miodrag Belodedici or Belodedić (b. 1964), Romanian footballer, born in Socol (Sokol).[12]

- Slavoliub Adnagi or Adnađ (b. 1965), the current Serbian member of the Chamber of Deputies.

- Andrei Ivanovitch (b. 1968) an international classical pianist and winner of a number of international competitions.

- Lavinia Miloșovici (b. 1976), Romanian gymnast, born in Lugoj.[13]

- Srdjan Luchin (b. 1986) Romanian footballer

- Iasmin Latovlevici (b. 1986) Romanian footballer

- Deian Boldor (b. 1995) Romanian footballer

|  Đоrđe Branković |  |  |  |  |  |  |

See also

References

- "Rezultatele finale ale Recensământului din 2011 - Tab8. Populaţia stabilă după etnie – judeţe, municipii, oraşe, comune" (in Romanian). National Institute of Statistics (Romania). 5 July 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Engel 2001, pp. 2-3.

- Oța 2014, p. 18.

- Györffy 1987b, pp. 306, 470.

- Cerović 1997.

- Cerović 1997, Oslobodilački pokreti u vreme Turaka.

- Dennis Deletant (January 1999). Communist Terror in Romania: Gheorghiu-Dej and the Police State, 1948-1965. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 142–. ISBN 978-1-85065-386-8.

- "Structura Etno-demografică a României". Edrc.ro. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "Structura Etno-demografică a României". Edrc.ro. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "Structura Etno-demografică a României". Edrc.ro. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- George Călinescu; Al Piru (1982). Istoria literaturii române: de la origini pînă în prezent. Editura Vlad & Vlad. p. 517. ISBN 978-973-95572-2-1.

- Olivera Bogavac (28 March 1990). "Tempo magazine #1257, pg. 11" (in Serbo-Croatian). Tempo magazine. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "Romanian Coach Keeps Up the Fight" Jane Perlez, New York Times, July 13, 1995

Sources

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme.

- Cerović, Ljubivoje (1997). "Srbi u Rumuniji od ranog srednjeg veka do današnjeg vremena". Projekat Rastko. Archived from the original on 2013-06-14.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Đurić-Milovanović, Aleksandral (2012). "Serbs in Romania: Relationship between Ethnic and Religious Identity" (PDF). Balcanica. 43: 117–142.

- Isailović, Neven G.; Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2015). "Serbian Language and Cyrillic Script as a Means of Diplomatic Literacy in South Eastern Europe in 15th and 16th Centuries". Literacy Experiences concerning Medieval and Early Modern Transylvania. Cluj-Napoca: George Bariţiu Institute of History. pp. 185–195.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers.

- Mitrović, Andrej (1969). Jugoslavija na Konferenciji mira 1919-1920. Beograd: Zavod za izdavanje udžbenika.

- Mitrović, Andrej (1975). Razgraničenje Jugoslavije sa Mađarskom i Rumunijom 1919-1920: Prilog proučavanju jugoslovenske politike na Konferenciji mira u Parizu. Novi Sad: Institut za izučavanje istorije Vojvodine.

- Pilat, Liviu (2010). "Mitropolitul Maxim Brancovici, Bogdan al III-lea şi legăturile Moldovei cu Biserica sârbă". Analele Putnei (in Romanian). 6 (1): 229–238.

- Sorescu-Marinković, Annemarie (2010). "Serbian Language Acquisition in Communist Romania" (PDF). Balcanica. 41: 7–31.

- Stojkovski, Boris; Ivanić, Ivana; Spăriosu, Laura (2018). "Serbian-Romanian Relations in the Middle Ages until the Ottoman Conquest" (PDF). Transylvanian Review. 27 (2): 217–229.

External links

- (in Romanian) Sârbii din Romania

- (in Serbian) Srbi u Rumuniji od ranog srednjeg veka do današnjeg vremena

- (in Romanian) "Sîrbii", on Divers online