Architecture of Serbia

The architecture of Serbia has a long, rich and diverse history. Some of the major European style from Roman to Postmodern are demonstrated, including renowned examples of Raška, Serbo-Byzantine with its revival, Morava, Baroque, Classical and Modern architecture, with prime examples in Brutalism and Streamline Moderne.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Serbia |

|---|

|

| People |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Sport |

|

Centuries of turbulent history of Serbia caused a great regional diversity and favored vernacular architecture. This made for a heterogeneous and diverse architectural style, with architecture differing from town to town. While this diversity may still be witnessed in small towns, the devastation of architectural heritage in the larger cities during World War II, and subsequent socialist influence on architecture resulted in specific mix of architectural styles.

Prehistory and antiquity

The northernmost Ancient Macedonian town was Kale-Krševica, which still today have the foundations of the Ancient Greek 5th century BC town. The Scordisci built the stone fortress of Singidunum, the Kalemegdan at Belgrade in the 3rd century BC, It has since been built on by Romans, Serbs, Turks, Austrians and show an example of continuing 2,300-year-old architecture, serving as one of the best landmarks in Belgrade.

The Romans left many traces of their six centuries of rule in the Serbian lands, including several fortifications and complexes such as the 3rd century AD Imperial palace of Galerius at Gamzigrad (Felix Romuliana) that was built at his birthplace after the victory against the Persians, the Mediana site in Niš (Naissus) from the 4th century, the ruins of the Moesia Superior capital Viminacium, former Roman capital and birthplace of several Roman Emperors Sirmium, and Byzantine city Justiniana Prima built by Justinian I, which was the seat of the Archbishopric of Justiniana Prima.

Medieval period

Prohor Pčinjski Monastery was founded 1067–1071 by the Byzantine emperor Romanus IV in honor of Saint Prohor of Pčinja.[1]

- Schools of architecture

- Raška architectural school

- Morava architectural school

- Vardar architectural school

Early Church architecture

Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul is one of the few remaining building from early Middle Ages and UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site. Prohor Pčinjski Monastery was founded 1067–1071 by the Byzantine emperor Romanus IV in honor of Saint Prohor of Pčinja.[1] Church architecture mostly developed under the patronage of the Serbian state. The most distinctive piece of medieval Serbian architecture was the Studenica monastery founded by Stefan Nemanja, the founder of medieval Serbia in c. 1190. This monastery also featured significant works of art including its Byzantine style fresco paintings. Its church also features extensive sculptures based on Psalms and the Dormition of the Theotokos. UNESCO added this monastery to its list of World Cultural Heritage sites in 1986. It was the model for other monasteries at Mileševa, Sopoćani and the Visoki Dečani.

The influence of Byzantine art became more influential after the capture of Constantinople in 1204 in the Fourth Crusade when many Greek artists fled to Serbia. Their influence can be seen at the Church of the Ascension at Mileševa as well as in the wall paintings at the Church of the Holy Apostles at Peć and at the Sopoćani Monastery. Icons also formed a significant part of church art.

The influence of Byzantine architecture reached its peak after 1300 including the rebuilding of the Our Lady of Ljeviš (c1306-1307) and Church of St. George at Staro Nagoričane as well as the Gračanica monastery. Church decorative paintings also developed further in the period.

The Visoki Dečani monastery in Metohija was built between 1330 and 1350. Unlike other Serbian monasteries of the period, it was built with Romanesque features by master-builders under the monk Vitus of Kotor. Its frescoes feature 1000 portraits portraying all of the major themes of the New Testament. The cathedral features iconostasis, hegumen's throne and carved royal sarcophagus. In 2004, UNESCO listed the Dečani Monastery on the World Heritage List.

There was a further spate of church building as the Serbian state contracted to the Morava basin in the late 14th century. Prince Stefan Lazarević was a poet and patron of the arts who founded the church at Resava at Morava with the wall paintings having a theme of parables of Christ with the people portrayed wearing feudal Serbian costumes.

- Ecclesiastical monuments

- Petrova church, 800 AD, Stari Ras

- Đurđevi stupovi, 1166, Novi Pazar

- Our Lady of Ljeviš, 12th century, Prizren

- Studenica monastery, 1190, Kraljevo

- Patriarchate of Peć, 13th century, Peć

- Sopoćani monastery, 1265, Stari Ras

- Mileševa monastery, 1236, Prijepolje

- Visoki Dečani, 1327, Dečani

- Gračanica Monastery, 1321, Gračanica is an example of the Serbo-Byzantine Style (UNESCO World Heritage Site)

- Saint Archangels Monastery, 1343, Prizren

Studenica monastery (1196), an example of unique medieval Serbian architecture, UNESCO World Heritage Site

Studenica monastery (1196), an example of unique medieval Serbian architecture, UNESCO World Heritage Site Žiča Monastery (1207-1217), the coronational site of the Serbian kings

Žiča Monastery (1207-1217), the coronational site of the Serbian kings The Patriarchate of Peć is the historical residence of Serbian Archbishops, UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Patriarchate of Peć is the historical residence of Serbian Archbishops, UNESCO World Heritage Site_-_by_Pudelek..jpg.webp) Serbian Orthodox Visoki Dečani monastersy, built in the 14th century, UNESCO World Heritage Site

Serbian Orthodox Visoki Dečani monastersy, built in the 14th century, UNESCO World Heritage Site Serbian Orthodox Gračanica monastery, built in the 14th century, UNESCO World Heritage Site

Serbian Orthodox Gračanica monastery, built in the 14th century, UNESCO World Heritage Site

Serbo-Byzantine style

This is an ecclesiastical architectural style that flourished in the Serbian Late Middle Ages, which was developed through fusing contemporary Byzantine architecture with Raskan influences to form a new style. By the end of 13th and in the first half of 14th century the Serbian state enlarged over Macedonia, Epirus and Thessaly up to the Aegean Sea. On these new territories Serbian art was even more influenced by the Byzantine art tradition.

Gračanica, which was entirely rebuilt by King Milutin in 1321, is the most beautiful monument of Serbian architecture from the 14th century.[2] The church of this monastery is an example of a construction that achieved the highest degree of architecture not only in the Byzantine form but in the creation of an original and freestyle exceeding its models. The wall creation in steps is one of the basic characteristics of this temple. The Kings's Church in Studenica, characterized as an ideal church, was built in the first decades of the 14th century.

By the end of the third decade of the 14th century the Patriarchate of Peć had finally been shaped. The exterior of the Patriarchate is a vision of shapes characteristic of contemporary Serbian architecture. On the major part of the outer walls paint decoration was used instead of stone relief and brick and stone decoration. A typical Serbo-Byzantine church has a rectangular foundation, with a major dome in the center with smaller domes around the center one. The inside of the church is covered with frescos that illustrate various biblical stories and portrays Serbian saints.

Ottoman architecture in Serbia

The territory of what is now the Republic of Serbia was part of the Ottoman Empire throughout the Early Modern period, especially Central Serbia, unlike Vojvodina which has passed to Habsburg rule starting from the end of the 17th century (with several takeovers of Central Serbia as well). Ottoman culture significantly influenced the region, in architecture, cuisine, language, and dress, especially in arts, and Islam.

Altun-Alem Mosque, Novi Pazar, XVI century

Altun-Alem Mosque, Novi Pazar, XVI century.jpg.webp) Mehmed Paša Sokolović's Fountain, Belgrade, 1576/77

Mehmed Paša Sokolović's Fountain, Belgrade, 1576/77 Islam-aga's Mosque, Niš, 1720

Islam-aga's Mosque, Niš, 1720

Modernity

Baroque

During the short-lived Austrian rule over Belgrade, a Baroque quarter was built, with a square and several monumental buildings.[4] After the reconquest of city by Ottoman Turks, all Baroque buildings were demolished.[4][5] Most Serbian Orthodox churches were built with all the characteristics of Baroque churches built in the Austrian administered regions. The churches usually had a bell tower, and a single nave building with the iconostasis inside the church covered with Renaissance-style paintings. These churches can mostly be found in Zemun and Vojvodina province.

Serbo-Byzantine Revival

The XIX century was a time of development of Serbian nationalism, which sought to develop a "national style" in architecture too, in line with national romanticism ideas. Within the broader movement of historicism, in parallel to neoclassical architecture, Serbia saw the development in particular of a Byzantine Revival architecture style. Other types of historicisms have had less of an impact in Serbia, though there are some examples of Gothic Revival architecture such as the Kapetanovo castle from 1904.

Serbia's modern sacral architecture got its main impetus from the dynastic burial church in Oplenac which was commissioned by member of the Karađorđević dynasty in 1909.[6] With the arrival of Russian émigré artist after the October revolution, Belgrade's main governmental edifices were planned by eminent Russian architects trained in Russian Empire.[7][8] It was King Aleksandar I. who was the patron of the neobyzantine movement.[9] Its main proponents were Aleksandar Deroko, Momir Korunović, Branko Krstić, Petar Krstić, Grigorijji Samojlov and Nikolay Krasnov. Their main contribution were Beli dvor, the Church of Saint Sava, St. Mark's Church, Belgrade. After the communist era ended Mihailo Mitrović and Nebojša Popović were proponents of new tendencies in sacral architecture which used classic examples in the Byzantine tradition.[10]

.jpg.webp)

House of Vuk's Foundation in Belgrade by Branko Tanazević, 1879

House of Vuk's Foundation in Belgrade by Branko Tanazević, 1879_1.JPG.webp) Crypt of Oplenac mausoleum by Nikolay Krasnov, 1910

Crypt of Oplenac mausoleum by Nikolay Krasnov, 1910 Old telephone exchange in Belgrade by Branko Tanazević, 1923

Old telephone exchange in Belgrade by Branko Tanazević, 1923 Old Post Office by Momir Korunović, 1929

Old Post Office by Momir Korunović, 1929

Art Nouveau and Secession style

The Art Nouveau and Vienna Secession style flourished in the north of the country at the turn of the XX century, when the Vojvodina region was still part of the Hungarian kingdom under the Habsburgs. Subotica and Zrenjanin host particularly remarkable buildings from the period. Novi Sad[11] and Belgrade were not immune from the architectural novelty either.

- Novi Sad: Bank of Vojvodina (1904), Novi Sad Synagogue (1909), Tomin's Palace (1909)[12]

- Subotica: Synagogue (1901), City Hall, City Library, Raichle Palace

.jpg.webp) Bank of Vojvodina (1904)

Bank of Vojvodina (1904) Novi Sad Synagogue (1909)

Novi Sad Synagogue (1909) Subotica Synagogue (1902)e Interior during renovation

Subotica Synagogue (1902)e Interior during renovation_w_Suboticy.jpg.webp) Raichle Palace, Subotica (1904)

Raichle Palace, Subotica (1904) Subotica City Hall (1910)[13]

Subotica City Hall (1910)[13]

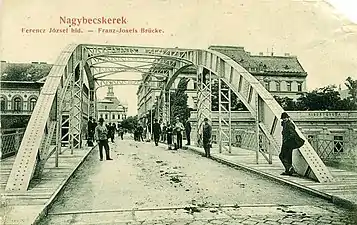

- Zrenjanin: Lipot Goldšmit's House,[14] City Hall, Dunđerski Palace, Bence House, Small Bridge,

Lipot Goldšmit's House, 1870s

Lipot Goldšmit's House, 1870s Zrenjanin City Hall, 1890

Zrenjanin City Hall, 1890 Palace of the wealthy Dunđerski family, 1906

Palace of the wealthy Dunđerski family, 1906 Bence House, Zrenjanin, 1909

Bence House, Zrenjanin, 1909 Small Bridge, Zrenjanin 1910

Small Bridge, Zrenjanin 1910

- Belgrade: Hotel Moskva (1908), Vučo’s House on the Sava River (1908), Uros Predic's Studio (1908), Mika Alas's House (1910),

Belgrade Cooperative, 1882

Belgrade Cooperative, 1882.jpg.webp) Hotel Moskva (1908)

Hotel Moskva (1908)

_02.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Mika Alas's House (1910)

Mika Alas's House (1910)

Royalist Yugoslav period

Yugoslav architecture emerged in the first decades of the 20th century before the establishment of the state; during this period a number of South Slavic creatives, enthused by the possibility of statehood, organized a series of art exhibitions in Serbia in the name of a shared Slavic identity. Following governmental centralization after the 1918 creation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, this initial bottom-up enthusiasm began to fade. Yugoslav architecture became more dictated by an increasingly concentrated state authority which sought to establish a unified state identity.[15]

Beginning the 1920s, Yugoslav architects began to advocate for architectural modernism, viewing the style as the logical extension of progressive national narratives. The Group of Architects of the Modern Movement, an organization founded in 1928 by architects Branislav Kojić, Milan Zloković, Jan Dubovy, and Dušan Babić pushed for the widespread adoption of modern architecture as the "national" style of Yugoslavia to transcended regional differences. Despite these shifts, differing relationships to the west made the adoption of modernism inconsistent in Yugoslavia WWII. Of all Yugoslavian cities, Belgrade has the highest concentration of modernist structures.[16][17] Air Force Command by Dragiša Brašovan is one of the biggest interwar modernist buildings in Belgrade.

- Interwar modernism

Hotel Avala by Viktor Lukomski, modernism combined with traditional architectural elements, 1928

Hotel Avala by Viktor Lukomski, modernism combined with traditional architectural elements, 1928_2012-09-17_17-38-08.jpg.webp) Veterans' Club Building, 1932-1939

Veterans' Club Building, 1932-1939 Palace Albanija, 1939, the first skyscraper in Southeast Europe

Palace Albanija, 1939, the first skyscraper in Southeast Europe

- Art Nouveau and Art Deco

Embassy of France by Roger-Henri Expert and Josif Najman, 1933

Embassy of France by Roger-Henri Expert and Josif Najman, 1933.jpg.webp)

BIGZ building by Dragiša Brašovan, 1940

BIGZ building by Dragiša Brašovan, 1940

- Interwar academic style

Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts building, 1922

Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts building, 1922 Ministries of Forestry and Agriculture, façade by Nikolay Krasnov, 1923

Ministries of Forestry and Agriculture, façade by Nikolay Krasnov, 1923

The Parliament of Serbia, and the headquarters of the Serbian Post, erected in 1938

The Parliament of Serbia, and the headquarters of the Serbian Post, erected in 1938

Socialist Yugoslav period

_t%C3%A9r%252C_szemben_a_Jugoszl%C3%A1v_Szakszervezeti_Sz%C3%A9kh%C3%A1z_(Dom_sindikata_Jugoslavije)._Fortepan_31525.jpg.webp)

The architecture of Yugoslavia was characterized by emerging, unique, and often differing national and regional narratives.[19] As a socialist state remaining free from the Iron Curtain, Yugoslavia adopted a hybrid identity that combined the architectural, cultural, and political leanings of both Western liberal democracy and Soviet communism.[20][21][22]

Socialist realism (1945–48)

Immediately following the Second World War, Yugoslavia's brief association with the Eastern Bloc ushered in a short period of socialist realism. Centralization within the communist model led to the abolishment of private architectural practices and the state control of the profession. During this period, the governing Communist Party condemned modernism as "bourgeois formalism," a move that caused friction among the nation's pre-war modernist architectural elite.[23]

- Dom Sindikata, 1947

Modernism (1948–92)

Socialist realist architecture in Yugoslavia came to an abrupt end with Josip Broz Tito's 1948 split with Stalin. In the following years the nation turned increasingly to the West, returning to the modernism that had characterized pre-war Yugoslav architecture.[17] During this era, modernist architecture came to symbolize the nation's break from the USSR (a notion that later diminished with growing acceptability of modernism in the Eastern Bloc).[23][24] The nation's postwar return to modernism is perhaps best exemplified in Vjenceslav Richter's widely acclaimed 1958 Yugoslavia Pavilion at Expo 58, the open and light nature of which contrasted the much heavier architecture of the Soviet Union.[25] A number of architects from Serbia made important modernistic buildings across Africa and Middle East.[26] Architect Mihajllo Mitrović was one of the several notable authors from the period. He is best known for modernistic buildings inspired by Art-Nouveau and Western City Gate.[27]

Belgrade Fair – Hall 1, Europe's largest dome and the world's largest dome between 1957 and 1965

Belgrade Fair – Hall 1, Europe's largest dome and the world's largest dome between 1957 and 1965 Ušće Towers, 1964 and Museum of Contemporary Art (bottom left), 1958

Ušće Towers, 1964 and Museum of Contemporary Art (bottom left), 1958 Hotel Sloboda in Šabac by Slobodan Janjić, 1977

Hotel Sloboda in Šabac by Slobodan Janjić, 1977 Beograđanka tower by Branko Pešić, 1974

Beograđanka tower by Branko Pešić, 1974 SPC Vojvodina (Hala), 1981

SPC Vojvodina (Hala), 1981

Spomeniks in Serbia

During this period, the Yugoslav break from Soviet socialist realism combined with efforts to commemorate World War II, which together led to the creation of an immense quantity of abstract sculptural war memorials, known today as spomenik[28]

Monument to Kosmaj Partisan Detachment, Belgrade

Monument to Kosmaj Partisan Detachment, Belgrade

Leskovac Memorial Park, by Bogdan Bogdanović, 1971

Leskovac Memorial Park, by Bogdan Bogdanović, 1971

Shrine to the fallen freedom fighters, Vlasotince, by Bogdan Bogdanović, 1975

Shrine to the fallen freedom fighters, Vlasotince, by Bogdan Bogdanović, 1975

Brutalism

In the late 1950s and early 1960s Brutalism began to garner a following within Yugoslavia, particularly among younger architects, a trend possibly influenced by the 1959 disbandment of the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne.[29] Besides numerous brutalist buildings in the capital, other notable examples can be found Požarevac, Arilje, Užice, Sremska Mitrovica and other parts of the country.[30]

- Museum of Yugoslavia (1962) by Mihajlo Janković[31]

- Novi Beograd town hall (1967) by Stojan Maksimovic and Branislav Jovin[31]

- Toblerone building (1963) by Rista Šekerinski

- 25 May Sportcenter (1975) by Ivan Antić[32]

- Belgrade's Eastern City Gate (1976) by Vera Ćirković

- Belgrade's Western City Gate (1977) by Mihajlo Mitrović

- Sava Centar (1979) by Stojan Maksimović

- Blocks 22, 23, 28, 30, 61, 62, 63, New Belgrade[31]

Decentralization

With 1950s decentralization and liberalization policies in SFR Yugoslavia, architecture became increasingly fractured along ethnic lines. Architects increasingly focused on building with reference to the architectural heritage of their individual socialist republics in the form of critical regionalism.[33] Growing distinction of individual ethnic architectural identities within Yugoslavia was exacerbated with the 1972 decentralization of the formerly centralized historical preservation authority, providing individual regions further opportunity to critically analyze their own cultural narratives.[15]

Crowne Plaza Belgrade by Stojan Maksimović, 1979

Crowne Plaza Belgrade by Stojan Maksimović, 1979 Hyatt Regency Belgrade, 1990

Hyatt Regency Belgrade, 1990 Museum of Aviation, by Ivan Štraus 1989

Museum of Aviation, by Ivan Štraus 1989

Contemporary period

The international style, which had arrived in Yugoslavia already in the 1980s, took over the scene in Belgrade after the wars and isolation of the 1990s. Big real estate projects, including Sava City and the redevelopment of the Ušće Towers, led the ground, with little respect for the local architecturale heritage.

Before and also after the Yugoslav wars numerous architects left Serbia and continued their work in a number of European, American and African countries, creating several hundreds of building.[4]

In 2015, an agreement was reached with Eagle Hills (a UAE company) on the Belgrade Waterfront (Beograd na vodi) deal, for the construction of a new part of the city on currently undeveloped wasteland by the riverside. This project, officially started in 2015 and is one of the largest urban development projects in Europe, will cost at least 3.5 billion euros.[34][35] According to Srdjan Garcevic, "Vaguely contemporary but somehow cheap-looking, it is planted illegally in the middle of the city on unstable soil – serving the interests of the anonymous lucky few."[36]

Sava City (Savograd), by Mario Jobst and Miodrag Trpković (2004-2010)

Sava City (Savograd), by Mario Jobst and Miodrag Trpković (2004-2010) Crystal Hall, Zrenjanin (2006)

Crystal Hall, Zrenjanin (2006) Ada Bridge (2008-2011)

Ada Bridge (2008-2011).jpg.webp) Beograd na vodi, 2014-ongoing

Beograd na vodi, 2014-ongoing

References

- "Zapostavljena svetinja". www.novosti.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- Ćurčić 1979.

- "Туристичка организација Града Врања Turistička organizacija Grada Vranja - Пашин конак". 2016-03-04. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- "Projekat Rastko: Istorija srpske kulture". www.rastko.rs. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- Васиљевић, Бранка. "Кавијар, октопод, топла чоколада..." Politika Online. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- Aleksandar Kadijević: Byzantine architecture as inspiration for serbian new age architects. Katalog der SANU anlässlich des Byzantinologischen Weltkongresses 2016 und der Begleitausstellung in der Galerie der Wissenschaften und Technik in der Serbischen Akademie der Wissenschaften und Künste. Serbian Committee for Byzantine Studies, Belgrade 2016, ISBN 978-86-7025-694-1, S. 87.

- "Београд из руског угла". Politika Online. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "Uticaj ruskih arhitekata u Beogradu". www.novosti.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- Aleksandar Kadijević: Byzantine architecture as inspiration for serbian new age architects. Katalog der SANU anlässlich des Byzantinologischen Weltkongresses 2016 und der Begleitausstellung in der Galerie der Wissenschaften und Technik in der Serbischen Akademie der Wissenschaften und Künste. Serbian Committee for Byzantine Studies, Belgrade 2016, ISBN 978-86-7025-694-1, S. 62.

- Aleksandar Kadijević 2016: Between Artistic Nostalgia and Civilisational Utopia: Byzantine Reminiscences in Serbian Architecture of the 20th Century. Lidija Merenik, Vladimir Simić, Igor Borozan (Hrsg.) 2016: IMAGINING THE PAST THE RECEPTION OF THE MIDDLE AGES IN SERBIAN ART FROM THE 18TH TO THE 21ST CENTURY. Ljubomir Maksimovic & Jelena Trivan (Hrsg.) 2016: BYZANTINE HERITAGE AND SERBIAN ART I–III. The Serbian National Committee of Byzantine Studies, P.E. Službeni glasnik, Institute for Byzantine Studies, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Hier S. 177 (Academia:PDF)

- "Art magazin - Secesija u Novom Sadu". www.artmagazin.info.

- ""Palata Tomin" u Novom Sadu – Palmculture". Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "Градска кућа Суботица | Међуопштински завод за заштиту споменика културе Суботица". 2015-09-12. Archived from the original on 2015-09-12. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "Zgrada trgovca Lipota Goldšmita". Zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture Zrenjanin. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- Deane, Darren (2016). Nationalism and Architecture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781351915793.

- Đorđević, Zorana (2016). "Identity of 20th Century Architecture in Yugoslavia: The Contribution of Milan Zloković". Култура/Culture. 6.

- Babic, Maja (2013). "Modernism and Politics in the Architecture of Socialist Yugoslavia, 1945-1965" (PDF). University of Washington.

- "Palace of Serbia". architectuul.com. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- Farago, Jason (2018-07-19). "The Cement Mixer as Muse". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- Glancey, Jonathan (2018-07-17). "Yugoslavia's forgotten brutalist architecture". CNN Style. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- McGuirk, Justin (2018-08-07). "The Unrepeatable Architectural Moment of Yugoslavia's "Concrete Utopia"". ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- Vladimir., Kulić (2012). Modernism in-between : the mediatory architectures of socialist Yugoslavia. Jovis Verlag. ISBN 9783868591477. OCLC 814446048.

- Alfirević, Đorđe; Simonović Alfirević, Sanja (2015). "Urban housing experiments in Yugoslavia 1948-1970" (PDF). Spatium (34): 1–9.

- Kulić, Vladimir (2012). "An Avant-Garde Architecture for an Avant-Garde Socialism: Yugoslavia at EXPO '58". Journal of Contemporary History. 47 (1): 161–184. doi:10.1177/0022009411422367. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 23248986.

- Niebyl, Donald (2020-03-29). "10 Works of Yugoslav Modernist Architecture in Africa & the Middle East". spomenikdatabase. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- Niebyl, Donald (2020-03-03). "Mihajlo Mitrović's singular Art-Nouveau inspired modernism in Vrnjačka Banja". spomenikdatabase. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- Kulić, Vladmir. "Edvard Ravnikar's Liquid Modernism: Architectural Identity in a Network of Shifting References" (PDF). New Constellations New Ecologies.

- di Radmila Simonovic, Ricerca (2014). "New Belgrade, Between Utopia and Pragmatism" (PDF). Sapienza Università di Roma.

- Alfirevic, Djordje; Simonovic Alfirevic, Sanja (2017-12-01). "Brutalism in Serbian Architecture: Style or Necessity? [Brutalizam u srpskoj arhitekturi: stil ili nužnost?]". Facta universitatis - series Architecture and Civil Engineering. 15. doi:10.2298/FUACE160805028A.

- kami (2019-08-29). "Guide to Belgrade brutalist architecture - over 20 concrete masterpieces". Kami and the Rest of the World. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "25 May Sportcenter". architectuul.com. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- Entertainment, The only biannual Magazine for Architectural. "YUGOTOPIA: The Glory Days of Yugoslav Architecture On Display". pinupmagazine.org. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 August 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Siniša Mali: "Beograd na vodi" najveći projekat u Evropi". Telegraf.rs.

- Balkan Insight, Serbia’s History is Carved in Stone in Belgrade

Further reading

- Jasna Bjeladinović-Jergić (1995). "Traditional architecture". The history of Serbian Culture. Rastko.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Ćurčić, Slobodan (1979). Gračanica: King Milutin's Church and Its Place in Late Byzantine Architecture. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Đorđević, Života; Pejić, Svetlana, eds. (1999). Cultural Heritage of Kosovo and Metohija. Belgrade: Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of the Republic of Serbia.

- Đurić, Vojislav J. (1995). "Art in the Middle ages". The history of Serbian Culture. Rastko.

- Gavrilović, Zaga (2001). Studies in Byzantine and Serbian Medieval Art. London: The Pindar Press.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers.

- Janićijević, Jovan, ed. (1990). Serbian Culture Through Centuries: Selected List of Recommended Reading. Belgrade: Yugoslav Authors' Agency.

- Janićijević, Jovan, ed. (1998). The Cultural Treasury of Serbia. Belgrade: Idea, Vojnoizdavački zavod, Markt system.

- Vojislav Korać (1995). "Architecture in medieval Serbia". The history of Serbian Culture. Rastko.

- Krstić, Branislav (2003). Saving the Cultural Heritage of Serbia and Europe in Kosovo and Metohia. Belgrade: Coordination Center of the Federal Government and the Government of the Republic of Serbia for Kosovo and Metohia.

- Ivica Mlađenović (1995). "Modern Serbian architecture". The history of Serbian Culture. Rastko.

- Peić, Sava (1994). Medieval Serbian Culture. London: Alpine Fine Arts Collection.

- Petković, Vesna; Peić, Sava (2013). Serbian Medieval Cultural Heritage. Belgrade: Dereta.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Subotić, Gojko (1998). Art of Kosovo: The Sacred Land. New York: The Monacelli Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of Serbia. |