Slavery in Iran

The History of slavery in Iran (Persia) during various ancient, medieval, and modern periods is sparsely catalogued.

Slavery in Pre-Achaemenid Iran

Slaves are attested[1] in the cuneiform record of the ancient Elamites, a non-Persian people who inhabited modern southwestern Iran, including the ancient cities of Anshan and Susa, and who were eventually incorporated into the Achaemenid Empire. Because of their participation in cuneiform culture, the Elamites are one of the few pre-Achaemenid civilizations of Iran to leave written attestations of slavery, and details of slavery among the Gutians, Kassites, Medes, Mannaeans, and other peoples of Bronze Age Iran are largely unrecorded.

Classical Antiquity

Slavery in the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BC)

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Slavery was an existing institution in Egypt, Media and Babylonia before the rise of the Achaemenid empire.

The most common word used to designate a slave in the Achaemenid was bandaka-, which was also used to express general dependence. In his writing, Darius I uses this word to refer to his satraps and generals. Therefore, Greek writers of the time expressed that all Persian people were slaves to their king. Other terms used to describe slaves within the empire could also have other meanings, such as "kurtaš" and "māniya-", which could mean hired or indentured workers in some contexts.[2]

Herodotus has mentioned enslavement with regards to rebels of the Lydians who revolted against Achaemenid rule and captured Sardis.[3] He has also mentioned slavery after the rebellion of Egypt in the city of Barce[4] during the time of Cambyses and the assassination of Persian Satrap in Egypt. He also mentions the defeat of Ionians, and their allies Eretria who supported the Ionians and subsequent enslavement of the rebels and supporting population.[5]

Under the Achaemenids, Persian nobles in Babylonia and other conquered states became large slave owners. They recruited a substantial number of their domestic slaves from these vanquished peoples. The Babylonians were required to supply an annual tribute of 500 boys. Information on privately owned slaves is scarce, but there are surviving cuniform documents from Babylonia and the Persepolis Administrative Archives which record slave sales and contracts.[2]

On the whole, in the Achaemenid empire, there was only small number of slaves in relation to the number of free persons. Usually, captives were prisoners of war that were recruited from those that rebelled against Achaemenid rule.[2]

According to Dandamayev:[2]

The basis of agriculture was the labor of free farmers and tenants and in handicrafts the labor of free artisans, whose occupation was usually inherited within the family, likewise predominated. In these countries of the empire, slavery had already undergone important changes by the time of the emergence of the Persian state. Debt slavery was no longer common. The practice of pledging one’s person for debt, not to mention self-sale, had totally disappeared by the Persian period. In the case of nonpayment of a debt by the appointed deadline, the creditor could turn the children of the debtor into slaves. A creditor could arrest an insolvent debtor and confine him to debtor’s prison. However, the creditor could not sell a debtor into slavery to a third party. Usually the debtor paid off the loan by free work for the creditor, thereby retaining his freedom.

Slavery in Parthian Iran (c. 238 BC–224 AD)

According to Plutarch, there were many "slaves" in the army of the Parthian general Surena.[6] However, the actual meaning of the term "slaves" (doûloi, servi) mentioned in this context is disputed, as it may be pejorative rather than literal.[7][8] Other than this mention, slave-soldiers are not securely attested in Iran until the Islamic period.

Plutarch also mentions that after the Romans were defeated in the Battle of Carrhae all the surviving Roman legionnaires were enslaved by the Parthians. Though not directly stated, it is implied Roman POWs in Parthia were commonly sold into slavery.

Slavery in Sassanid Iran (c. 224–642 AD)

Under this period Roman prisoners of war were used in farming in Babylonia, Shush and Persis.[9]

Sassanid Laws of Slavery

Some of the laws governing the ownership and treatment of slaves can be found in the legal compilation called the Matigan-i Hazar Datistan, a collection of rulings by Sasanian judges.[10] Principles that can be inferred from the laws include:

- Sources of slaves were both foreign (e.g., non-Zoroastrians captives from warfare or raiding or slaves imported from outside the Empire by traders) or domestic (e.g., hereditary slaves, children sold into slavery by their fathers, or criminals enslaved as punishment). Some cases suggest that a criminal's family might also be condemned to servitude. At the time of the manuscript's composition, Iranian slavery was hereditary on the mother's side (so that a child of a free man and a slave woman would be a slave), although the author reports that in earlier Persian history it may have been the opposite, being inherited from the father's side.

- Slave-owners had the right to the slaves' income.

- While slaves were formally chattel (property) and were liable to the same legal treatment as nonhuman property (for example, they could be sold at will, rented, owned jointly, inherited, given as security for a loan, etc.), Sasanian courts did not treat them completely as objects; for example, slaves were allowed to testify in court in cases concerning them, rather than only permitted to be represented by their owners.

- Slaves were often given to the Zoroastrian Fire Temples as a pious offering, in which case they and their descendants would become temple-slaves.

- Excessive cruelty towards slaves could result in the owners' being brought to court; a court case involving a slave whose owner tried to drown him in the Tigris River is recorded, though without stating the outcome of the case.

- If a non-Zoroastrian slave, such as a Christian slave, converted to Zoroastrianism, he or she could pay his or her price and attain freedom; i.e., as long as the owner was compensated, manumission was required.

- Owners could also voluntarily manumit their slaves, in which case the former slave became a subject of the Sasanian King of Kings and could not lawfully be re-enslaved later. Manumissions were recorded, which suggests that a freedman who was challenged would be able to document their free status.

- Uniquely in comparison to Western slave systems, Sasanian slavery recognized partial manumission (relevant in the case of a jointly owned slave, only some of whose owners were willing to manumit). In case of a slave who was, e.g., one-half manumitted, the slave would serve in alternating years.

To free a slave (irrespective of his or her faith) was considered a good deed.[11] Slaves had some rights including keeping gifts from the owner and at least three days of rest in the month.[12]

Medieval Iran

Early Modern Iran

Slavery under Nader Shah and his successors (c. 1736–1796 AD)

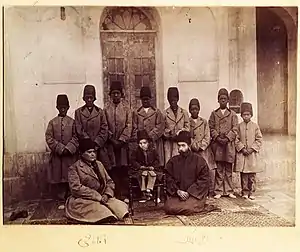

Slavery in Qajar Iran (c. 1796–1925 AD)

At the beginning of the 19th century both white and black slaves were traded in Iran. The 1828 war with Russia put an end to the import of white slaves from the Russian Empire borderlands as it undermined the trade in Circassians and Georgians, which both Iran and neighboring Turkey had been practicing for quite some time. At the same time and under various pressures the British Empire decided to curb the slave trade through the Indian Ocean. Consequently, by 1870 the trade in African slaves to Iran through the Indian Ocean had been significantly diminished. Although the diplomatic efforts of the Russians and the British did result in a decline in the trade, slavery was still common in Iran under the Qajar dynasty and it was not until the first half of twentieth century that slavery would be officially abolished in Iran under Reza Shah Pahlavi.[13]

Modern Period

Abolition of slavery (1929 AD)

What ultimately led to the abolition of the slave trade and the emancipation of slaves in Iran were internal pressures for reform.[14] On February 7, 1929 the Iranian National Parliament ratified an anti-slavery bill that outlawed the slave trade or any other claim of ownership over human beings. The bill also empowered the government to take immediate action for the emancipation of all slaves.[15]

Original text of Iranian Slavery Abolition Act of 1929 is as follows:[16]

“Single Article” – In Iran, no one shall be recognized as slave and every slave will be emancipated upon arrival at Iran`s territorial soil or waters. Every person who purchases or vends a human as slave or treats with a human in another ownership manner or acts as an intermediary in trading or transit of slaves, shall be sentenced to one to three years of correctional imprisonment. Indication – Having been informed about or referring of someone who has been subjected to trading or treatment as a slave, every official is obligated to provide him with means of liberation, immediately, and to inform the district court for guilt’s prosecution.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Slavery after abolition

See also

References

- Zadok, Ran (1994). "Elamites and Other Peoples from Iran and the Persian Gulf Region in Early Mesopotamian Sources". Iran. 32: 39 and 43. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- M. A. Dandamayev, BARDA and BARDADĀRĪ in Encyclopedia Iranica

- Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, 1195 pp., Eisenbrauns Publishers, 2006, ISBN 1-57506-120-1, ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7, p.37

- J. D. Fage, R. A. Oliver, The Cambridge History of Africa: From C.500 BC to AD1050, 858 pp., Cambridge University Press, 1979, ISBN 0-521-21592-7, ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3 (see page 112)

- David Sansone, Ancient Greek Civilization , 226 pp., Blackwell Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-631-23236-2, ISBN 978-0-631-23236-0 (see page 85)

- Ehsan Yar-Shater, W. B. Fisher, The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods , 1488 pp., Cambridge University Press, 1983, ISBN 0-521-24693-8, ISBN 978-0-521-24693-4 (see p.635)

- http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/arsacids-ii

- http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/class-system-iii

- Evgeniĭ Aleksandrovich Beliyayev, Arabs, Islam and the Arab Caliphate in the Early Middle Ages, 264 pp., Praeger Publishers, 1969 (see p.13)

- K. D. Irani, Morris Silver, Social Justice in the Ancient World , 224 pp., Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995, ISBN 0-313-29144-6, ISBN 978-0-313-29144-9 (see p.87)

- K. D. Irani, Morris Silver, Social Justice in the Ancient World , 224 pp., Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995, ISBN 0-313-29144-6, ISBN 978-0-313-29144-9 (see p.87)

- K. D. Irani, Morris Silver, Social Justice in the Ancient World , 224 pp., Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995, ISBN 0-313-29144-6, ISBN 978-0-313-29144-9 (see p.87)

- Mirzai, Behnaz A (2004). Slavery, the abolition of the slave trade, and the emancipation of slaves in Iran (1828-1928) (Ph.D.). York University. OCLC 66890745.

- Mirzai, Behnaz A (2004). Slavery, the abolition of the slave trade, and the emancipation of slaves in Iran (1828-1928) (Ph.D.). York University. OCLC 66890745.

- Law for prohibition of slave trade and liberation of slaves at the point of entry, 1 Iranian National Parliament 7, Page 156 (1929).

- Law for prohibition of slave trade and liberation of slaves at the point of entry, 1 Iranian National Parliament 7, Page 156 (1929).

Further reading

Last number(s) indicate pages:

A. Perikhanian (1983). "Iranian Society and Law". In Ehsan Yar-Shater; William Bayne Fisher; Ilya Gershevitch (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. 5: Institutions. Cambridge University Press. pp. 634–640. ISBN 9780521246934.

Anthony A. Lee, “Enslaved African Women in Nineteenth-Century Iran: The Life of Fezzeh Khanom of Shiraz,” Iranian Studies (May 2012).

Amir H. Mehryar, F. Mostafavi, & Homa Agha (2001-07-05). "Men and Family Planning in Iran" (PDF). The IUSSP XXIVth General Population Conference in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, August 18–24, 2001. p. 4.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)