Slavery in the 21st century

Contemporary slavery, also known as modern slavery or neo-slavery, refers to institutional slavery that continues to occur in present-day society. Estimates of the number of slaves today range from around 38 million[1] to 46 million,[2][3] depending on the method used to form the estimate and the definition of slavery being used.[4] The estimated number of slaves is debated, as there is no universally agreed definition of modern slavery;[5] those in slavery are often difficult to identify, and adequate statistics are often not available. The International Labour Organization[6] estimates that, by their definitions, over 40 million people are in some form of slavery today. 24.9 million people are in forced labor, of whom 16 million people are exploited in the private sector such as domestic work, construction or agriculture; 4.8 million persons in forced sexual exploitation, and 4 million persons in forced labor imposed by state authorities. 15.4 million people are in forced marriage.

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Definition

The Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, an agency of the United States Department of State, says that "'modern slavery', 'trafficking in persons', and 'human trafficking' have been used as umbrella terms for the act of recruiting, harboring, transporting, providing or obtaining a person for compelled labor or commercial sex acts through the use of force, fraud, or coercion". Besides these, a number of different terms are used in the US federal Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 and the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, including "involuntary servitude", "slavery" or "practices similar to slavery", "debt bondage", and "forced labor".[7]

According to American professor Kevin Bales, co-founder and former president of the non-governmental organization and advocacy group Free the Slaves, modern slavery occurs "when a person is under the control of another person who applies violence and force to maintain that control, and the goal of that control is exploitation".[8] The impact of slavery is expanded when targeted at vulnerable groups such as children. According to this definition, research from the Walk Free Foundation based on its Global Slavery Index 2018 estimated that there were about 40.3 million slaves around the world.[8][9] In another estimate that suggests the number is around 45.8 million, it is estimated that around 10 million of these contemporary slaves are children.[3] Bales warned that, because slavery is officially abolished everywhere, the practice is illegal, and thus more hidden from the public and authorities. This makes it impossible to obtain exact figures from primary sources. The best that can be done is to estimate based on secondary sources, such as UN investigations, newspaper articles, government reports, and figures from NGOs.[8] Modern slavery persists for many of the same reasons older variations did: it is an economically beneficial practice despite the ethical concerns. The problem has been able to escalate in recent years due to the disposability of slaves and the fact that the cost of slaves has dropped significantly.[10]

Causes

Since slavery has been officially abolished, enslavement no longer revolves around legal ownership, but around illegal control. Two fundamental changes are the move away from the forward purchase of slave labour, and the existence of slaves as an employment category. While the statistics suggest that the 'market' for exploitative labour is booming, the notion that humans are purposefully sold and bought from an existing pool is outdated. While such basic transactions do still occur, in contemporary cases people become trapped in slavery-like conditions in various ways.[11]

Modern slavery is often seen as a by-product of poverty. In countries that lack education and the rule of law, anarchy and poor societal structure can create an environment that fosters the acceptance and propagation of slavery. Slavery is most prevalent in impoverished countries and those with vulnerable minority communities, though it also exists in developed countries. Tens of thousands toil in slave-like conditions in industries such as mining, farming, and factories, producing goods for domestic consumption or export to more prosperous nations.[12]

In the older form of slavery, slave-owners spent more on getting slaves. It was more difficult for them to be disposed of. The cost of keeping them healthy was considered a better investment than getting another slave to replace them. In modern slavery people are easier to get at a lower price so replacing them when exploiters run into problems becomes easier. Slaves are then used in areas where they could easily be hidden while also creating a profit for the exploiter. Slaves are more attractive for unpleasant work, and less for pleasant work.

Modern slavery can be quite profitable,[13] and corrupt governments tacitly allow it, despite it being outlawed by international treaties such as Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery and local laws. Total annual revenues of traffickers were estimated in 2014 to over $150 billion dollars,[14] though profits are substantially lower. American slaves in 1809 were sold for around the equivalent of US$40,000 in today's money.[15] Today, a slave can be bought for $90.[15]

Bales explains, “This is an economic crime ... People do not enslave people to be mean to them; they do it to make a profit.”[16]

Types

Slavery by Descent and Chattel Slavery

Slavery by descent, also called chattel slavery, is the form most often associated with the word "slavery". In chattel slavery, the enslaved person is considered the personal property (chattel) of someone else, and can usually be bought and sold. It stems historically either from conquest, where a conquered person is enslaved, as in the Roman Empire or Ottoman Empire, or from slave raiding, as in the Atlantic slave trade. In the 21st Century, almost every country has legally abolished chattel slavery, but the number of people currently enslaved around the world is far greater than the number of slaves during the historical Atlantic slave trade.

Since the 2014 Civil War in Libya, and the subsequent breakdown of law and order, there have been reports of enslaved migrants being sold in public, open slave markets in the country.[17]

Mauritania has a long history with slavery. Chattel slavery was formally made illegal in the country but the laws against it have gone largely unenforced. It is estimated that around 90,000 people (over 2% of Mauritania's population) are slaves. In addition, forced marriage and child prostitution are not criminalised.[18]

Debt bondage can also be passed down to descendants, like chattel slavery.

Those trapped in the system of sexual slavery in the modern world are often effectively chattel, especially when they are forced into prostitution.

Government-forced labor and conscription

Government-forced labor, also known as state-sponsored labor, is defined by the International Labor Organization as events "which persons are coerced to work through the use of violence or intimidation, or by more subtle means such as accumulated debt, retention of identity papers or threats of denunciation to immigration authorities."[19] When the threats come from the government the threats can be much different. Many governments that participate in forced labor shut down their connections with the surrounding countries to prevent citizens from leaving.

In North Korea, the government forces many people to work for the state, both inside and outside North Korea itself, sometimes for many years. The 2018 Global Slavery Index estimated that 2.8 million people were slaves in the country.[20] The value of all the labor done by North Koreans for the government is estimated at US$975 million, with dulgyeokdae (youth workers) forced to do dangerous construction work, and inminban (women and girl workers) forced to make clothing in sweatshops. The workers are often unpaid.[21] Additionally, North Korea's army of 1.2 million conscripted soldiers is often made to work on construction projects unrelated to defense, including building private villas for the elite.[21] The government has had as many as 100,000 workers abroad.[22]

In Eritrea, an estimated 300,000 to 400,000 people are in an indefinite military service program which amounts to mass slavery, according to UN investigators. Their report also found sexual slavery and other forced labor.[23]

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection blocked the importation of black diamonds from Zimbabwe in October 2019, according to a report by Bloomberg News. Zimbabwe, in turn, accused the U.S. government of lying about forced labor at a state-owned diamond mine.[24]

About 35–40 countries are currently enforcing military conscription of some sort, even if it is only temporary service.

It is imperative to note that government-forced labor comes in different forms as governments have also been known to participate in forced labor practices that do not include military service. In Uzbekistan, for example, the government coerces students and state workers to harvest cotton, of which the country is a main exporter, every year; forcefully abandoning their other responsibilities in the process.[25] Of course this is not the only type of slavery found in this example as the use of students, including those in primary, secondary, and higher education, means that child labor is also prominent.[26]

Prison labor

In China's system of labor prisons (formerly called laogai), millions of prisoners have been subject to forced, unpaid labor. The laogai system is estimated to currently house between 500,000 and 2 million prisoners,[27] and to have caused tens of millions of deaths.[28] In parallel with laogai, China operated the smaller Re-education through labor system of prisons up until 2013.[29] In addition to both of these, China is also operating forced labor camps in Xinjiang, imprisoning hundreds of thousands (possibly as many as a million) of Muslims, Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities and political dissidents.[30][31]

In 1865, the United States passed the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which banned slavery and involuntary servitude "except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted",[32] providing a legal basis for slavery to continue in the country.[33] As of 2018, many prisoners in the US perform work. In Texas, Georgia, Alabama and Arkansas, prisoners are not paid at all for their work.[34] In other states, as of 2011, prisoners were paid between $0.23 and $1.15 per hour.[35] Federal Prison Industries paid inmates an average of $0.90 per hour in 2017.[33] In many cases the penal work is forced, with prisoners being punished by solitary confinement if they refuse to work.[36][37] From 2010 to 2015[38] and again in 2016[39] and in 2018,[40] some prisoners in the US refused to work, protesting for better pay, better conditions, and for the end of forced labor. Strike leaders are currently punished with indefinite solitary confinement.[41][42] Forced prison labor occurs in both public/government-run prisons and private prisons. The prison labor industry makes over $1 billion USD per year selling products that inmates make, while inmates are paid very little or nothing in return.[33] In California, 2,500 incarcerated workers are fighting wildfires for only $1 per hour through the CDCR's Conservation Camp Program, which saves the state as much as $100 million a year.[43]

In North Korea, tens of thousands of prisoners may be held in forced labor camps. Prisoners suffer harsh conditions and have been forced to dig their own graves[44] and to throw rocks at the dead body of another prisoner.[45] At Yodok Concentration Camp, children and political prisoners were subject to forced labor.[45] Yodok closed in 2014 and its prisoners were transferred to other prisons.[46]

Bonded labor

Bonded labor, also known as debt bondage and peonage, occurs when people give themselves into slavery as a security against a loan or when they inherit a debt from a relative.[47] The cycle begins when people take extreme loans under the condition that they work off the debt. The "loan" is designed so that it can never be paid off, and is often passed down for generations. People become trapped in this system working ostensibly towards repayment though they are often forced to work far past the original amount they owe. They work under the force of threats and abuse. Sometimes the debts last a few years, and sometimes the debts are even passed onto future generations.[48]

Bonded labor is used across a variety of industries in order to produce products for consumption around the world.[47] It is most common in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal.

In India, the majority of bonded laborers are Dalits (Untouchables) and Adivasis (indigenous tribespeople).[48] Puspal, a former brick kiln worker in Punjab, India stated in an interview to antislavery.org; "We do not stop even if we are ill - what if our debt is increasing? So we don't dare to stop."[49] In India, when compared to the price of land, paid labor or oxen, the price of slaves costs 95% less than in the past. While a strong law was enacted, The Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, convictions are almost impossible and the fines are often less than $2.[50]

Forced migrant labor

People may be enticed to migrate with the promise of work, only to have their documents seized and be forced to work under the threat of violence to them or their families.[51] Undocumented immigrants may also be taken advantage of; as without legal residency, they often have no legal recourse. Along with sex slavery, this is the form of slavery most often encountered in wealthy countries such as the United States, in Western Europe, and in the Middle East.

In the United Arab Emirates, some foreign workers are exploited and more or less enslaved. The majority of the UAE resident population are foreign migrant workers rather than local Emirati citizens. The country has a kafala system which ties migrant workers to local Emirati sponsors with very little government oversight. This has often led to forced labor and human trafficking.[52] In 2017, the UAE passed a law to protect the rights of domestic workers.[53]

Vietnamese teenagers are trafficked to the United Kingdom and forced to work in illegal cannabis farms. When police raid the cannabis farms, trafficked victims are typically sent to prison.[54][55]

In the United States, various industries have been known to take advantage of forced migrant labor. During the 2010 New York State Fair, 19 migrants who were in the country legally from Mexico to work in a food truck were essentially enslaved by their employer.[56] The men were paid around ten percent of what they were promised, worked far longer days than they were contracted to, and would be deported if they had quit their job as this would be a violation of their visas.[57]

Sex slavery

Along with migrant slavery, forced prostitution is the form of slavery most often encountered in wealthy regions such as the United States, in Western Europe, and in the Middle East. It is the primary form of slavery in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia, particularly in Moldova and Laos. Many child sex slaves are trafficked from these areas to the West and the Middle East. An estimated 20% of slaves to date are active in the sex industry.[58] Sexual exploitation can also become a form of debt bondage when enslavers insist that victims work in the sex industry to pay for basic needs and transportation.[59]

In 2005, the Gulf Times reported that boys from Nepal had been lured to India and enslaved for sex. Many of these boys had also been subject to male genital mutilation (castration).[60]

Many of those who become victims of sex slavery initially do so willingly under the guise that they will be performing traditional sex work, only to become trapped for extended periods of time, such as those involved in Nigeria's human trafficking circuit.[61]

Forced marriage and child marriage

._Molla_Nasreddin.jpg.webp)

Mainly driven by the culture in certain regions, early or forced marriage is a form of slavery that affects millions of women and girls all over the world. When families cannot support their children, the daughters are often married off to the males of wealthier, more powerful families. These men are often significantly older than the girls. The females are forced into lives whose main purpose is to serve their husbands. This often fosters an environment for physical, verbal and sexual abuse.

Forced marriages also happen in developed nations. In the United Kingdom there were 3,546 reports to the police of forced marriage over three years from 2014 to 2016.[62]

In the United States over 200,000 minors were legally married from 2002 to 2017, with the youngest being only 10 years old. Most were married to adults.[63] Currently 48 US states, as well as D.C. and Puerto Rico, allow marriage of minors as long as there is judicial consent, parental consent or if the minor is pregnant.[64][65] In 2017–2018, several states began passing laws to either restrict child marriage[66][67][68] or ban it altogether.[69]

Bride-buying is the act of purchasing a bride as property, in a similar manner to chattel slavery. It can also be related to human trafficking.

Child labor

Children comprise about 26% of the slaves today.[58] Although children can legally engage in certain forms of work, children can also be found in slavery or slavery-like situations. Forced begging is a common way that children are forced to participate in labor without their consent. Most are domestic workers or work in cocoa, cotton or fishing industries. Many are trafficked and sexually exploited. In war-torn countries, children have been kidnapped and sold to political parties to use as child soldiers. Forced child labor is the dominant form of slavery in Haiti.

Child soldiers are children who may be trafficked from their homes and forced or coerced by armed forces. The armed forces could be government armed forces, paramilitary organizations, or rebel groups. While in these groups the children may be forced to work as cooks, guards, servants or spies.[70] It is common for both boys and girls to be sexually abused while in these groups.

Fishing industry

According to Human Rights Watch, Thailand's billion-dollar fish export industry remains plagued with human rights maltreatment in spite of government vows to stamp out servitude in its angling industry.[71] Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with 248 fishermen, it documented the forced labor of trafficked workers in the Thai fishing industry. Trafficking victims are often tricked by brokers' false promises of "good" factory jobs, then forced onto fishing boats where they are trapped, bought and sold like livestock, and held against their will for months or years at a time, forced to work grueling 22-hour days in dangerous conditions. Those who resist or try to run away are beaten, tortured, and often killed.[72] This is commonplace because of the disposability of unfree laborers.

Despite some improvements, the situation has not changed much[73] since a large-scale survey of almost 500 fishers in 2012, that found almost one in five "reported working against their will with the penalty that would prevent them from leaving".[74]

Occupations

In addition to sex slavery, modern slaves are often forced to work in certain occupations. Common occupations include:

- Small-scale building work, such as laying driveways, and other labor.[75]

- Car washing by hand[75]

- Domestic servitude, sometimes with sexual exploitation.[75]

- Nail salons (cosmetic). Many people are trafficked from Vietnam to the UK for this work.[75]

- Fishing, mainly associated with Thailand's sea food industry.[76][77]

- Manufacturing – Many prisoners in the US are forced to manufacture products as diverse as mattresses, spectacles, underwear, road signs and body armour.[78]

- Agriculture and forestry – Prisoners in the United States and China are often forced to do farming and forestry work. See prison farm.

- In North Korea, dulgyeokdae (youth workers) are often forced to work in construction and inminban (women workers) are forced to work in clothing sweatshops.[21]

Signs that someone may have been forced into slavery include a lack of identity documents, lack of personal possessions, clothing that is unsuitable or has seen much wear, poor living conditions, a reluctance to make eye contact, unwillingness to talk, and unwillingness to seek help. In the UK people are encouraged to report suspicions to a modern-slavery telephone helpline.[75]

Trafficking

The United Nations have defined human trafficking as follows:

The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.[79]

According to United States Department of State data, as of 2013, an "estimated 600,000 to 820,000 men, women, and children [are] trafficked across international borders each year, approximately 70 percent are women and girls and up to 50 percent are minors. The data also illustrates that the majority of transnational victims are trafficked into commercial sexual exploitation."[80] However, "the alarming enslavement of people for purposes of labor exploitation, often in their own countries, is a form of human trafficking that can be hard to track from afar". It is estimated that 50,000 people are trafficked every year in the United States.[81]

In recent years, the internet and popular social networking sites have become tools that traffickers use to find vulnerable people who they can then exploit. A 2017 Reuters report discusses how a woman is suing Facebook for negligence as she speculated that executives were aware of a situation that occurred back in 2012 where was sexually abused and trafficked by someone posing as her "friend".[82] Social media and smartphone apps are also used to sell the slaves.[83]

In 2016, a Washington Post article exposed that the Obama administration placed migrant children with human traffickers.[84] They failed to do proper background checks of adults who claimed the children, allowed sponsors to take custody of multiple unrelated children, and regularly placed children in homes without visiting the locations. Several Guatemalan teens were found being held captive by traffickers and forced to work at a local egg farm in Ohio.

Organizational efforts against slavery

Government actions

In the last two decades, as slavery has become more widely recognized as a formidable global epidemic, multiple governmental organizations have begun taking action to address the problem. The US State Department's annual Trafficking In Persons Report assigns grades to every nation in a tier-system based "not on the size of the country’s problem but on the extent of governments’ efforts to meet the TVPA’s minimum standards for the elimination of human trafficking".[85]

The governments credited with the strongest response to modern slavery are the Netherlands, the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Australia, Portugal, Croatia, Spain, Belgium, Germany and Norway.[86]

In the United Kingdom, the British government passed the Modern Slavery Act 2015, supported by major reforms in the legal system instituted through the Criminal Finances Act 2017, effective from September 30, 2017. Under the latter act, there is transparency in regards to interbank information sharing with law enforcement agencies to help to crack down on money laundering agencies related to contemporary slavery. The Act also aims at reducing the incidence of tax evasion attributed to the modern slave trade conducted under the domain of the law.[87] Despite this, the government has been refusing asylum and deporting children trafficked to the UK as slaves. Several British charities have claimed this puts the deportees at risk of being subject to control by slavery gangs a second time, and deters child victims from coming forward with information.[88]

The British government has taken specific steps to ensure that modern slavery risks are identified and managed in government supply chains.[89][90]

In contrast, the governments accused of taking the least action against it are North Korea, Eritrea, Equatorial Guinea, Hong Kong, Central African Republic, Papua New Guinea, Guinea, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan.[86]

While countries can be scrutinized for not taking ample action to combat slavery within their borders, there is little that can be done as there are few diplomatic options for low-risk nations to consider.

Private initiatives

In September 2013, the three anti-slavery donors, the Legatum Foundation, Humanity United and the Walk Free Foundation founded the Freedom Fund. As of December 2019, the Freedom Fund is reported to have impacted 686,468 lives, liberated 27,397 people from modern slavery and helped 56,181 previously out-of-school children to receive either formal or non-formal education, in Nepal, Ethiopia, India and Thailand. Meanwhile, in October 2014, the Freedom Fund, Polaris and the Walk Free Foundation launched the Global Modern Slavery Directory, which was the first publicly searchable database of over 770 organisations working to end forced labor and human trafficking.[91][92][93]

Statistics

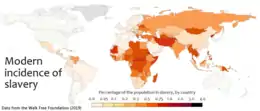

Modern slavery is a multibillion-dollar industry with just the forced labor aspect generating US $150 billion each year.[94] The Global Slavery Index (2018) estimated that roughly 40.3 million individuals are currently caught in modern slavery, with 71% of those being female, and 1 in 4 being children.[95][96] As of 2018, the countries with the most slaves were: India (8 million), China (3.86 million), Pakistan (3.19 million), North Korea (2.64 million), Nigeria (1.39 million), Indonesia (1.22 million), Democratic Republic of the Congo (1 million), Russia (794,000) and the Philippines (784,000).[97]

Various jurisdictions now require large commercial organizations to publish a slavery and human trafficking statement in regard to their supply chains each financial year (e.g. California,[98] UK, Australia[99]). The Walk Free Foundation reported in 2018 that 40.3 million people worldwide live in conditions that can be described as slavery. According to the foundation, more than 400,000 of those are in the United States. Andrew Forrest, founder of the organisation, was quoted as saying that "the United States is one of the most advanced countries in the world yet has more than 400,000 modern slaves working under forced labor conditions".[100] In March 2020, released British police records showed that the number of modern slavery offences recorded has increased by more than 50%, from 3,412 cases in 2018 to 5,144 cases in 2019. This coincided with a 68% increase in calls and submissions to the modern slavery helpline over the same time period.[101]

See also

References

- "Forced labour – Themes". Ilo.org. Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2015-01-15.

- Kelly, Annie (1 June 2016). "46 million people living as slaves, latest global index reveals". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "What is modern slavery?". Anti-Slavery International. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- "Walk Free". The Minderoo Foundation. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- Paz-Fuchs, Amir. "Badges of Modern Slavery". The Modern Law Review. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

- International Labour Organization (19 September 2017). "Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage". International Labour Organization.

- "What is Modern Slavery?". Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. United States Department of State. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Maral Noshad Sharifi (8 June 2016). "Er zijn 45,8 miljoen moderne slaven" [There are 45.8 million modern slaves]. NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Fudge, Judy (Fall 2018). "Slavery and Unfree Labour: The Politics of Naming, Framing, and Blaming". Labour – via ProQuest.

- "Cost of slaves falls to historic low". CNN Freedom Project. CNN. 7 March 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- Nolan, Justine; Boersma, Martijn (September 2019). Addressing Modern Slavery (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2019). ISBN 9781742244631. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- "Modern Slavery: Its Root Causes and the Human Toll". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Siddarth Kara, Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

- "Human Trafficking Numbers". Human Rights First. December 7, 2017. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Slavery Today". Free The Slaves. 05-13-19. Retrieved 2013-08-18. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Bales, Kevin (March 2010). "Kevin Bales | Speaker | TED". www.ted.com. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Graham-Harrison, Emma (10 April 2017). "Migrants from west Africa being 'sold in Libyan slave markets'". the Guardian.

- "Country Data - Global Slavery Index".

- "The Meanings of Forced Labour". International Labour Organization.

- "North Korea has 2.6 million 'modern slaves', new report estimates". Washington Post.

- Borowiec, Steven. "North Koreans perform $975 million worth of forced labor each year". Los Angeles Times.

- "Pyongyang’s overseas workforce once totaled more than 100,000 people" https://www.wsj.com/articles/north-korean-workers-flock-home-as-sanctions-deadline-hits-11576837803

- "As many as 400,000 enslaved in Eritrea, UN estimates". CBC News.

- "Zimbabwe accuses U.S. of lying about diamond-mining forced labor". Freedom United. Oct 7, 2019. Retrieved Oct 13, 2019.

- "End Uzbek Cotton Crimes". Anti-Slavery International. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- Bhat, Bilal Ahmad (2011-05-01). "Socioeconomic Dimensions of Child Labor in Central Asia". Problems of Economic Transition. 54 (1): 84–99. doi:10.2753/pet1061-1991540108. ISSN 1061-1991. S2CID 153335200.

- "Laogai Handbook" (PDF). The Laogai Research Foundation. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2008. Retrieved October 18, 2008. p. 6.

- Chang, Jung and Halliday, Jon. Mao: The Unknown Story. Jonathan Cape, London, 2005. p. 338:

By the general estimate China's prison and labor camp population was roughly 10 million in any one year under Mao. Descriptions of camp life by inmates, which point to high mortality rates, indicate a probable annual death rate of at least 10 per cent.

- Moore, Malcolm (2014-01-09). "China abolishes its labour camps and releases prisoners". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "Former inmates of China's Muslim 'reeducation' camps tell of brainwashing, torture". Washington Post.

- "Xinjiang's New Slavery". Foreign Policy.

- "13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov.

- "Prison labour is a billion-dollar industry, with uncertain returns for inmates". The Economist. March 16, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- Walker, Jason (September 6, 2016). "Unpaid Labor in Texas Prisons Is Modern-Day Slavery". Truthout. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- Diaz, Norisa (April 4, 2013). "California governor seeks end to federal prison oversight". World Socialist Web Site.

- Benns, Whitney (September 21, 2015). "American Slavery, Reinvented". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- Shahshahani, Azadeh (May 17, 2018). "Why are for-profit US prisons subjecting detainees to forced labor?". The Guardian. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- Hedges, Chris (June 22, 2015). "America's Slave Empire". Truthdig. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- Speri, Alice (16 September 2016). "The Largest Prison Strike in U.S. History Enters Its Second Week". The Intercept.

- Lopez, German (August 22, 2018). "America's prisoners are going on strike in at least 17 states". Vox. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- Pilkington, Ed (August 21, 2018). "US inmates stage nationwide prison labor strike over 'modern slavery'". The Guardian. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- Fryer, Brooke (September 5, 2018). "US inmates sent to solitary confinement over 'prison slavery' strike". NITV News. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- "A New Form of Slavery? Meet Incarcerated Firefighters Battling California's Wildfires for $1 an Hour". Democracy Now!. September 12, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- Evans, Stephen (14 June 2017). "How harsh is prison in North Korea?". BBC News.

- "'We were forced to throw rocks at a man being hanged': Prisoner exposes life inside notorious North Korea forced labour camp".

- "Camp 15 Gone But No Liberty for Prisoners". DailyNK. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- "Bonded Labor | Debt Bondage or Peonage - End Slavery Now". endslaverynow.org. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Network, Dalit Freedom. "Modern Slavery: Bonded Labor". Dalit Freedom Network. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- "What is bonded labour?". Anti-Slavery International. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- "Documents | National Human Rights Commission India" (PDF). nhrc.nic.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-03. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- Hodal, Kate; Chris Kelly; Felicity Lawrence (2014-06-10). "Revealed: Asian slave labor producing prawns for supermarkets in the US, UK". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

Fifteen migrant workers from Burma and Cambodia also told how they had been enslaved.

- "A Culture of Slavery: Domestic Workers in the United Arab Emirates - Human Rights Brief". 30 November 2016.

- "Is the Kafala System over in the UAE? Law Improving Domestic Worker Rights Approved". 26 September 2017.

- Amelia Gentleman (25 March 2017). "Trafficked and enslaved: the teenagers tending UK cannabis farms". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- Bridge, Rowan (17 August 2010). "Children work in 'cannabis farms'" – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- Eisenstadt, Marnie (2011-04-17). "State fair vendor abused workers from Mexico". syracuse.com. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- http://media.syracuse.com/news/other/contract.pdf

- "Forced labour, modern slavery, and human trafficking". International Labour Organization. 2017. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- "Human Trafficking and Slavery in the 21st Century". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- "Former sex worker's tale spurs rescue mission". Gulf Times. Gulf-Times.com. 10 April 2005. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

“I spent seven years in hell,” says Raju, now 21, trying hard not to cry. Thapa Magar took him to Rani Haveli, a brothel in Mumbai that specialized in male sex workers and sold him for Nepali Rs 85,000. A Muslim man ran the flesh trade there in young boys and girls, most of them lured from Nepal. For two years, Raju was kept locked up, taught to dress as a girl and castrated. Many of the other boys there were castrated as well. Beatings and starvation became a part of his life. “There were 40 to 50 boys in the place,” a gaunt, brooding Raju recalls. “Most of them were Nepalese.”

- "Nigeria's trafficking curse: the battle to dispel the black magic..." Reuters. 2018-09-18. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- Thousands enslaved in forced marriages across UK, investigation finds The Guardian

- "13,000 children a year are married in America".

- LII Staff (14 April 2008). "Marriage laws". LII / Legal Information Institute.

- "California Marriage Age Requirements Laws". FindLaw.

- "Arizona Sets Minimum Age for Marriage of Minors". 13 April 2018.

- "It's official: The marriage age is raised in NH - New Hampshire".

- Wulfhorst, Ellen. "Florida approves limit, but not ban, on child marriage".

- Thomsen, Jacqueline (10 May 2018). "Delaware becomes first state to ban child marriage".

- "What is Modern Slavery?". www.state.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- Kelly, Annie (2018-01-23). "Thai seafood: are the prawns on your plate still fished by slaves?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- A Shocking Look at Thailand’s Modern Day Slavery, Hilary Cadigan, Chiang Mai city news

- "Lawless Ocean: The Link Between Human Rights Abuses and Overfishing". Yale. E360. Retrieved 20 Nov 2019.

- Supang Chantavanich et al., Employment Practices and Working Conditions in Thailand’s Fishing Sector(Bangkok: ILO, 2013), p. 75.

- Abda Khan (20 September 2017). "Modern slavery in the UK is inflicting misery under our noses every day". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- "Thailand accused of failing to stamp out murder and slavery in fishing industry". The Guardian. 30 March 2017.

- "Human Trafficking, Slavery and Murder in Kantang's Fishing Industry". Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF).

- "Prison labour is a billion-dollar industry, with uncertain returns for inmates". The Economist. 16 March 2017.

- martin.margesin. "What is Human Trafficking?". www.unodc.org. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- "Introduction - Trafficking in Persons Report". US Department of State. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- "Economics and Slavery" (PDF). Du.edu. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- "Woman sues Facebook, claims site enabled sex trafficking". Reuters. 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- Slave markets found on Instagram and other apps BBC, 2019

- "Obama administration placed children with human traffickers, report says". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- "Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2018". Global Report on Trafficking in Persons. 2019-01-29. doi:10.18356/9805f543-en. ISBN 9789210475525. ISSN 2411-8443.

- India Tops Global Slavery Index With 18.35 Million People Enslaved, Huffington Post

- Criminal Finances Act 2017

- Home Office refusing asylum to growing number of child slavery victims, figures show The Independent

- Cabinet Office, Procurement Policy Note – Tackling Modern Slavery in Government Supply Chains: Action Note PPN 05/19 September 2019, accessed 2 January 2021

- Government Commercial Function,Tackling Modern Slavery in Government Supply Chains, published September 2019, accessed 2 January 2021

- "$100 Million Freedom Fund to Combat Modern-Day Slavery".

- "Campaigners launch first anti-slavery organizations database".

- "Global metrics".

- "Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labour". www.ilo.org. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- Global Slavery Index https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/2018/. Retrieved 2020-05-01. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_575479. Retrieved 2020-05-01. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Which countries have the highest rates of modern slavery and most victims?".

- "SB 657 Home Page". State of California - Department of Justice - Office of the Attorney General. 2015-03-31. Archived from the original on 2020-05-11. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Affairs, Home. "Modern Slavery Act 2018". www.legislation.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2020-04-14. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Helmore, Edward (July 19, 2018). "Over 400,000 people living in 'modern slavery' in US, report finds". The Guardian. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- "UK police record 51% rise in modern slavery offences in a year". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

External links

- UN Human Rights Council Special Rapporteur on Contemporary forms of slavery - Ohvhr.org

- The CNN Freedom Project: Ending Modern-Day Slavery, CNN

- Slavery collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- "Slave Labor collected news and commentary". The New York Times.

- Report on trafficking in human beings in Europe European Commission

- Historians Against Slavery

- Modern Slavery Laws: 21st Century Plague