Slavery in the Ottoman Empire

Slavery in the Ottoman Empire was a legal and significant part of the Ottoman Empire's economy and traditional society.[1] The main sources of slaves were wars and politically organized enslavement expeditions in North and East Africa, Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and the Caucasus. It has been reported that the selling price of slaves decreased after large military operations.[2] In Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), the administrative and political center of the Ottoman Empire, about a fifth of the 16th- and 17th-century population consisted of slaves.[3] Customs statistics of these centuries suggest that Istanbul's additional slave imports from the Black Sea may have totaled around 2.5 million from 1453 to 1700.[4]

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

| Social structure |

|---|

| Court and aristocracy |

| Millets |

| Rise of nationalism |

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Even after several measures to ban slavery in the late 19th century, the practice continued largely unabated into the early 20th century. As late as 1908, female slaves were still sold in the Ottoman Empire.[5] Sexual slavery was a central part of the Ottoman slave system throughout the history of the institution.[6][7]

A member of the Ottoman slave class, called a kul in Turkish, could achieve high status. Eunuch harem guards and janissaries are some of the better known positions a slave could hold, but female slaves were actually often supervised by them.

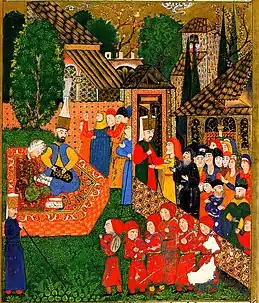

A large percentage of officials in the Ottoman government were bought slaves,[8] raised free, and integral to the success of the Ottoman Empire from the 14th century into the 19th. Many slave officials themselves owned numerous slaves, although the Sultan himself owned by far the most.[5] By raising and specially training slaves as officials in palace schools such as Enderun, where they were taught to serve the Sultan and other educational subjects, the Ottomans created administrators with intricate knowledge of government, and fanatic loyalty. The male establishment of this society created links of recorded information, even though speculation is present for European writings. However, women played and held the most important roles within the Harem institution.[9]

Early Ottoman slavery

In the mid-14th century, Murad I built an army of slaves, referred to as the Kapıkulu. The new force was based on the Sultan's right to a fifth of the war booty, which he interpreted to include captives taken in battle. The captives were trained in the sultan's personal service.[10] The devşirme system could be considered a form of slavery because the Sultans had absolute power over them. However, as the 'servant' or 'kul' of the sultan, they had high status within the Ottoman society because of their training and knowledge. They could become the highest officers of the state and the military elite, and most recruits were privileged and remunerated. Though ordered to cut all ties with their families, a few succeeded in dispensing patronage at home. Christian parents might thus implore, or even bribe, officials to take their sons. Indeed, Bosnian and Albanian Muslims successfully requested their inclusion in the system.[11][12]

Slaves were traded in special marketplaces called "Esir" or "Yesir" that were located in most towns and cities, central to the Ottoman Empire. It is said that Sultan Mehmed II "the Conqueror" established the first Ottoman slave market in Constantinople in the 1460s, probably where the former Byzantine slave market had stood. According to Nicolas de Nicolay, there were slaves of all ages and both sexes, most were displayed naked to be thoroughly checked – especially children and young women – by possible buyers.[13]

Ottoman slavery in Central and Eastern Europe

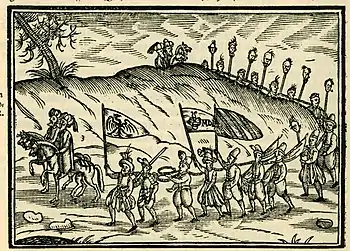

In the devşirme, which connotes "draft", "blood tax" or "child collection", young Christian boys from the Balkans and Anatolia were taken from their homes and families, converted to Islam, and enlisted into the most famous branch of the Kapıkulu, the Janissaries, a special soldier class of the Ottoman army that became a decisive faction in the Ottoman invasions of Europe.[14] Most of the military commanders of the Ottoman forces, imperial administrators, and de facto rulers of the Empire, such as Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, were recruited in this way.[15][16] By 1609, the Sultan's Kapıkulu forces increased to about 100,000.[17]

A Hutterite chronicle reports that in 1605, during the Long Turkish War, some 240 Hutterites were abducted from their homes in Upper Hungary by the Ottoman Turkish army and their Tatar allies, and sold into Ottoman slavery.[18][19] Many worked in the palace or for the Sultan personally.

Domestic slavery was not as common as military slavery.[17] On the basis of a list of estates belonging to members of the ruling class kept in Edirne between 1545 and 1659, the following data was collected: out of 93 estates, 41 had slaves.[17] The total number of slaves in the estates was 140; 54 female and 86 male. 134 of them bore Muslim names, 5 were not defined, and 1 was a Christian woman. Some of these slaves appear to have been employed on farms.[17] In conclusion, the ruling class, because of extensive use of warrior slaves and because of its own high purchasing capacity, was undoubtedly the single major group keeping the slave market alive in the Ottoman Empire.[17]

Rural slavery was largely a phenomenon endemic to the Caucasus region, which was carried to Anatolia and Rumelia after the Circassian migration in 1864.[20] Conflicts frequently emerged within the immigrant community and the Ottoman Establishment intervened on the side of the slaves at selective times.[21]

The Crimean Khanate maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East until the early eighteenth century. In a series of slave raids euphemistically known as the "harvesting of the steppe", Crimean Tatars enslaved East Slavic peasants.[22] The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia suffered a series of Tatar invasions, the goal of which was to loot, pillage, and capture slaves, the Slavic languages even developed a term for the Ottoman slavery (Polish: jasyr, based on Turkish and Arabic words for capture - esir or asir).[23][24] The borderland area to the south-east was in a state of semi-permanent warfare until the 18th century. It is estimated that up to 75% of the Crimean population consisted of slaves or freed slaves.[25] The 17th century Ottoman writer and traveller Evliya Çelebi estimated that there were about 400,000 slaves in the Crimea but only 187,000 free Muslims.[26] Polish historian Bohdan Baranowski assumed that in the 17th century the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (present-day Poland, Ukraine and Belarus) lost an average of 20,000 yearly and as many as one million in all years combined from 1500 to 1644.[26]

Prices and taxes

A study of the slave market of Ottoman Crete produces details about the prices of slaves. Factors such as age, skin color, virginity etc. significantly influenced prices. The most expensive slaves were those between 10 and 35 years of age, with the highest prices for European virgin girls 13–25 years of age and teenaged boys. The cheaper slaves were those with disabilities and sub-Saharan Africans. Prices in Crete ranged between 65 and 150 "esedi guruş" (see Kuruş). But even the lowest prices were affordable to only high income persons. For example, in 1717 a 12-year-old boy with mental disabilities was sold for 27 guruş, an amount that could buy in the same year 462 kg (1,019 lb) of lamb meat, 933 kg (2,057 lb) of bread or 1,385 l (366 US gal) of milk. In 1671 a female slave was sold in Crete for 350 guruş, while at the same time the value of a large two-floor house with a garden in Chania was 300 guruş. There were various taxes to be paid on the importation and selling of slaves. One of them was the "pençik" or "penç-yek" tax, literally meaning "one fifth". This taxation was based on verses of the Quran, according to which one fifth of the spoils of war belonged to God, to the Prophet and his family, to orphans, to those in need and to travelers. The Ottomans probably started collecting pençik at the time of Sultan Murad I (1362–1389). Pençik was collected both in money and in kind, the latter including slaves as well. Tax was not collected in some cases of war captives. With war captives, slaves were given to soldiers and officers as a motive to participate in war.[2]

The recapture of runaway slaves was a job for private individuals called "yavacis". Whoever managed to find a runaway slave would collect a fee of "good news" from the yavaci and the latter took this fee plus other expenses from the slaves' owner. Slaves could also be rented, inherited, pawned, exchanged or given as gifts.[2][27]

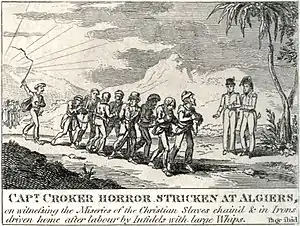

Barbary slave raids

For centuries, large vessels on the Mediterranean relied on European galley slaves supplied by Ottoman and Barbary slave traders. Hundreds of thousands of Europeans were captured by Barbary pirates and sold as slaves in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 19th centuries.[28][29] These slave raids were conducted largely by Arabs and Berbers rather than Ottoman Turks. However, during the height of the Barbary slave trade in the 16th, 17th, 18th centuries, the Barbary states were subject to Ottoman jurisdiction and for exception of Morocco were ruled by Ottoman pashas. Furthermore, many slaves captured by the Barbary corsairs were sold eastward into Ottoman territories before, during, and after Barbary's period of Ottoman rule.[30][31]

Notable occasions include the Turkish Abductions

Zanj slaves

As there were restrictions on the enslavement of Muslims and of "People of the Book" (Jews and Christians) living under Muslim rule, pagan areas in Africa became a popular source of slaves. Known as the Zanj (Bantu[32]), these slaves originated mainly from the African Great Lakes region as well as from Central Africa.[33] The Zanj were employed in households, on plantations and in the army as slave-soldiers. Some could ascend to become high-rank officials, but in general Zanj were inferior to European and Caucasian slaves.[34][35]

One way for Zanj slaves to serve in high-ranking roles involved becoming one of the African eunuchs of the Ottoman palace.[36] This position was used as a political tool by Sultan Murad III (r. 1574–1595) as an attempt to destabilize the Grand Vizier by introducing another source of power to the capital.[37]

After being purchased by a member of the Ottoman court, Mullah Ali was introduced to the first chief Black eunuch, Mehmed Aga.[38] Due to Mehmed Aga's influence, Mullah Ali was able to make connections with prominent colleges and tutors of the day, including Hoca Sadeddin Efendi (1536/37-1599), the tutor of Murad III.[39] Through the network he had built with the help of his education and the black eunuchs, Mullah Ali secured several positions early on. He worked as a teacher in Istanbul, a deputy judge, and an inspector of royal endowments.[38] In 1620, Mullah Ali was appointed as chief judge of the capital and in 1621 he became the kadiasker, or chief judge, of the European provinces and the first black man to sit on the imperial council.[40] At this time, he had risen to such power that a French ambassador described him as the person who truly ran the empire.[38]

Although Mullah Ali was often challenged because of his blackness and his connection to the African eunuchs, he was able to defend himself through his powerful network of support and his own intellectual productions. As a prominent scholar, he wrote an influential book in which he used logic and the Quran to debunk stereotypes and prejudice against dark-skinned people and to delegitimize arguments for why Africans should be slaves.[41]

Today, thousands of Afro Turks, the descendants of the Zanj slaves in the Ottoman Empire, continue to live in modern Turkey. An Afro-Turk, Mustafa Olpak, founded the first officially recognised organisation of Afro-Turks, the Africans' Culture and Solidarity Society (Afrikalılar Kültür ve Dayanışma Derneği) in Ayvalık. Olpak claims that about 2,000 Afro-Turks live in modern Turkey.[42][43]

East African slaves

The Upper Nile Valley and Abyssinia were also significant sources of slaves in the Ottoman Empire. Although the Christian Abyssinians defeated the Ottoman invaders, they did not tackle enslavement of southern pagans as long as they were paid taxes by the slave traders. Pagans and muslims from southern Ethiopian areas such as kaffa and jimma were taken north to Ottoman Egypt and also to ports on the Red Sea for export to Arabia and the Persian Gulf. In 1838, it was estimated that 10,000 to 12,000 slaves were arriving in Egypt annually using this route.[44] A significant number of these slaves were young women, and European travelers in the region recorded seeing large numbers of Ethiopian slaves in the Arab world at the time. The Swiss traveler Johann Louis Burckhardt estimated that 5,000 Ethiopian slaves passed through the port of Suakin alone every year,[45] headed for Arabia, and added that most of them were young women who ended up being prostituted by their owners. The English traveler Charles M. Doughty later (in the 1880s) also recorded Ethiopian slaves in Arabia, and stated that they were brought to Arabia every year during the Hajj pilgrimage.[46] In some cases, female Ethiopian slaves were preferred to male ones, with some Ethiopian slave cargoes recording female-to-male slave ratios of two to one.[47]

Slaves in the Imperial Harem

Very little is actually known about the Imperial Harem, and much of what is thought to be known is actually conjecture and imagination.[48] There are two main reasons for the lack of accurate accounts on this subject. The first was the barrier imposed by the people of the Ottoman society – the Ottoman people did not know much about the machinations of the Imperial Harem themselves, due to it being physically impenetrable, and because the silence of insiders was enforced.[48] The second was that any accounts from this period were from European travelers, who were both not privy to the information, and also inherently presented a Western bias and potential for misinterpretation by being outsiders to the Ottoman culture.[48] Despite the acknowledged biases by many of these sources themselves, scandalous stories of the Imperial Harem and the sexual practices of the sultans were popular, even if they were not true.[48] Accounts from the seventeenth century drew from both a newer, seventeenth century trend as well as a more traditional style of history-telling; they presented the appearance of debunking previous accounts and exposing new truths, while proceeding to propagate old tales as well as create new ones.[48] However, European accounts from captives who served as pages in the imperial palace, and the reports, dispatches, and letters of ambassadors resident in Istanbul, their secretaries, and other members of their suites proved to be more reliable than other European sources.[48] And further, of this group of more reliable sources, the writings of the Venetians in the sixteenth century surpassed all others in volume, comprehensiveness, sophistication, and accuracy.[48]

The concubines of the Ottoman Sultan consisted chiefly of purchased slaves. The Sultan's concubines were generally of Christian origin. Most of the elites of the Harem Ottoman Empire included many women, such as the sultan's mother, preferred concubines, royal concubines, children (princes / princess), and administrative personnel. The administrative personnel of the palace were made up of many high-ranking women officers, they were responsible for the training of Jariyes for domestic chores.[48][49] The mother of a Sultan, though technically a slave, received the extremely powerful title of Valide Sultan which raised her to the status of a ruler of the Empire (see Sultanate of Women). The mother of the Sultan played an substantial role in decision making for the Imperial Harem. One notable example was Kösem Sultan, daughter of a Greek Christian priest, who dominated the Ottoman Empire during the early decades of the 17th century.[50] Roxelana (also known as Hürrem Sultan), another notable example, was the favorite wife of Suleiman the Magnificent.[51] Many historians who study the Ottoman Empire, rely on the factual evidence of observers of the 16th and 17th century Islam. The tremendous growth of the Harem institution reconstructed the careers and roles of women in the dynasty power structure. There were harem women who were the mothers, legal wives, consorts, Kalfas, and concubines of the Ottoman Sultan. Only a handful of these harem women were freed from slavery and married their spouses. These women were : Hurrem Sulan , Nurbanu Sulan , Saifye Sultan (disput,e , Kosem Sulan , Gulnus Sul, , Perestu Sultan and Bezmiara Kadin. The Queen mothers who held the title Valide Sultan had only five of them that were freed slaves after they were concubines to the Sultan.

The concubines were guarded by enslaved eunuchs, themselves often from pagan Africa. The eunuchs were headed by the Kizlar Agha ("agha of the [slave] girls"). While Islamic law forbade the emasculation of a man, Ethiopian Christians had no such compunctions; thus, they enslaved and emasculated members of territories to the south and sold the resulting eunuchs to the Ottoman Porte.[52][53] The Coptic Orthodox Church participated extensively in the slave trade of eunuchs. Coptic priests sliced the penis and testicles off boys around the age of eight in a castration operation.[54]

The eunuch boys were then sold in the Ottoman Empire. The majority of Ottoman eunuchs endured castration at the hands of the Copts at Abou Gerbe monastery on Mount Ghebel Eter.[54] Slave boys were captured from the African Great Lakes region and other areas in Sudan like Darfur and Kordofan then sold to customers in Egypt.[55][52] During the operation, the Coptic clergyman chained the boys to tables and after slicing their sexual organs off, stuck bamboo catheters into the genital area, then submerged them in sand up to their necks. The recovery rate was 10 percent. The resulting eunuchs fetched large profits in contrast to eunuchs from other areas.[56][57][58]

Ottoman Sexual Slavery

Female sexual slavery was extremely common in the Ottoman empire and any child of a female slave were just as legitimate as any child born of a free woman.[59] This means that any child of a female slave could not be sold or given away. However, due to extreme poverty, some Circassian slaves and free people in the lower classes of Ottoman society felt forced to sell their children into slavery; this provided a potential benefit for the children as well, as slavery also held the opportunity for social mobility.[60] If a harem slave became pregnant, it also became illegal for her to be further sold in slavery, and she would gain her freedom upon her current owner's death.[60] Slavery in and of itself was long tied with the economic and expansionist activities of the Ottoman empire.[61] There was a major decrease in slave acquisition by the late eighteenth century as a result of the lessoning of expansionist activities.[61] War efforts were a great source of slave procurement, so the Ottoman empire had to find other methods of obtaining slaves because they were a major source of income within the empire.[61] The Caucasian War caused a major influx of Circassian slaves into the Ottoman market and a person of modest wealth could purchase a slave with a few pieces of gold.[61] At a time, Circassian slaves became the most abundant in the imperial harem.[61]

Circassians, Syrians, and Nubians were the three primary races of females who were sold as sex slaves (Cariye) in the Ottoman Empire.[62] Circassian girls were described as fair and light-skinned and were frequently enslaved by Crimean Tatars then sold to Ottoman Empire to live and serve in a Harem.[62] They were the most expensive, reaching up to 500 pounds sterling, and the most popular with the Turks. Second in popularity were Syrian girls, which came largely from coastal regions in Anatolia.[62] Their price could reach up to 30 pounds sterling. Nubian girls were the cheapest and least popular, fetching up to 20 pounds sterling.[63] Sex roles and symbolism in Ottoman society functioned as a normal action of power. The palace Harem excluded enslaved women from the rest of society.[64]

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, sexual slavery was not only central to Ottoman practice but a critical component of imperial governance and elite social reproduction.[65] Boys could also become sexual slaves, though usually they worked in places like bathhouses (hammam) and coffeehouses. During this period, historians have documented men indulging in sexual behavior with other men and getting caught.[66] Moreover, the visual illustrations during this period of exposing a sodomite being stigmatized by a group of people with Turkish wind instruments shows the disconnect between sexuality and tradition. However those that were accepted became tellaks (masseurs), köçeks (cross-dressing dancers) or sāqīs (wine pourers) for as long as they were young and beardless.[67] The "Beloveds" were often loved by former Beloveds that were educated and considered upper class.[66]

Some female slaves who were owned by women were sold as sex workers for short periods of time.[59] Women also purchased slaves, but usually not for sexual purposes, and most likely searched for slaves who were loyal, healthy, and had good domestic skills.[68] However, there were accounts of Jewish women owning slaves and indulging in forbidden sexual relationships in Cairo.[68] Beauty was also a valued trait when looking to buy a slave because they often seen as objects to show off to people.[68] While prostitution was against the law, there were very little recorded instances of punishment that came to shari'a courts for pimps, prostitutes, or for the people who sought out their services.[69] Cases that did punish prostitution usually resulted in the expulsion of the prostitute or pimp from the area they were in.[69] However, this does not mean that these people were not always receiving light punishments. Sometimes military officials took it upon themselves to enforce extra judicial punishment. This involved pimps being strung up on trees, destruction of brothels, and harassing prostitutes.[69]

Sexual slavery in the Ottoman empire also provided a social function because some slaves gained the status of their owner, or was passed on a distinguished person's lineage.[68] Slaves also had the right to inheritance. Some slaves were treated as family members, and were left with money, items, or were even granted their own freedom.[68] Sexual slavery was a means for social mobility in the Ottoman empire. The imperial harem was similar to a training institution for concubines, and served as a way to get closer to the Ottoman elite.[64] Parents from lower-class concubines especially had better opportunities for social mobility in the imperial harem because they could be trained for marriage to high-ranking military officials.[64] Some of the concubines had a chance for even greater power in Ottoman society if they became favorites of the sultan. [70] The sultan would keep a large number of girls as his concubines in the New Palace, which as a result became known as "the palace of the girls" in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[70] These concubines mainly consisted of young Christian slave girls. Accounts claim that the sultan would keep a concubine in the New Palace for a period of two months, during which time he would do with her as he pleased.[70] They would be considered eligible for the sultan's sexual attention until they became pregnant; if a concubine became pregnant, the sultan may take her as a wife and move her to the Old Palace where they would prepare for the royal child; if she did not become pregnant by the end of the two months, she would be married off to one of the sultan's high-ranking military men.[70] If a concubine became pregnant and gave birth to a daughter, she may still be considered for further sexual attention from the sultan.[70] The harem system was an important part of Ottoman-Egyptian society as well; it attempted to mimic the imperial harem in many ways, including the secrecy of the harem section of the household, where the women were kept hidden away from males that were outside of their own family, the guarding of the women by black eunuchs, and also having the function of training for becoming wives or concubines.[60]

Decline and suppression of Ottoman slavery

Responding to the influence and pressure of European countries in the 19th century, the Empire began taking steps to curtail the slave trade, which had been legally valid under Ottoman law since the beginning of the empire. One of the important campaigns against Ottoman slavery and slave trade was conducted in the Caucasus by the Russian authorities.[71]

A series of decrees were promulgated that initially limited the slavery of white persons, and subsequently that of all races and religions. In 1830, a firman of Sultan Mahmud II gave freedom to white slaves. This category included Circassians, who had the custom of selling their own children, enslaved Greeks who had revolted against the Empire in 1821, and some others.[72] Attempting to suppress the practice, another firman abolishing the trade of Georgians and Circassians was issued in October, 1854.[73]

Later, slave trafficking was prohibited in practice by enforcing specific conditions of slavery in sharia, Islamic law, even though sharia permitted slavery in principle. For example, under one provision, a person who was captured could not be kept a slave if they had already been Muslim prior to their capture. Moreover, they could not be captured legitimately without a formal declaration of war, and only the Sultan could make such a declaration. As late Ottoman Sultans wished to halt slavery, they did not authorize raids for the purpose of capturing slaves, and thereby made it effectively illegal to procure new slaves, although those already in slavery remained slaves.[74][75]

The Ottoman Empire and 16 other countries signed the 1890 Brussels Conference Act for the suppression of the slave trade. Clandestine slavery persisted into the early 20th century. A circular by the Ministry of Internal Affairs in October 1895 warned local authorities that some steamships stripped Zanj sailors of their "certificates of liberation" and threw them into slavery. Another circular of the same year reveals that some newly freed Zanj slaves were arrested based on unfounded accusations, imprisoned and forced back to their lords.[72]

An instruction of the Ministry of Internal Affairs to the Vali of Bassora of 1897 ordered that the children of liberated slaves be issued separate certificates of liberation to avoid both being enslaved themselves and separated from their parents. George Young, Second Secretary of the British Embassy in Constantinople, wrote in his Corpus of Ottoman Law, published in 1905, that at time of writing the slave trade in the Empire was practiced only as contraband.[72] The trade continued until World War I. Henry Morgenthau, Sr., who served as the U.S. Ambassador in Constantinople from 1913 until 1916, reported in his Ambassador Morgenthau's Story that there were gangs that traded white slaves during those years.[76] He also wrote that Armenian girls were sold as slaves during the Armenian Genocide of 1915.[77][78]

The Young Turks adopted an anti-slavery stance in the early 20th century.[79] Sultan Abdul Hamid II's personal slaves were freed in 1909 but members of his dynasty were allowed to keep their slaves. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk ended legal slavery in the Turkish Republic. Turkey waited until 1933 to ratify the 1926 League of Nations convention on the suppression of slavery. Illegal sales of girls were reported in the early 1930s. Legislation explicitly prohibiting slavery was adopted in 1964.[80]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yasyr. |

Notes

- "Supply of Slaves".

- Spyropoulos Yannis, Slaves and freedmen in 17th- and early 18th-century Ottoman Crete, Turcica, 46, 2015, p. 181, 182.

- Welcome to Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History.

- The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420–AD 1804

- Eric Dursteler (2006). Venetians in Constantinople: Nation, Identity, and Coexistence in the Early Modern Mediterranean. JHU Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8018-8324-8.

- Wolf Von Schierbrand (March 28, 1886). "Slaves sold to the Turk; How the vile traffic is still carried on in the East. Sights our correspondent saw for twenty dollars--in the house of a grand old Turk of a dealer" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Madeline C. Zilfi Women and slavery in the late Ottoman Empire Cambridge University Press, 2010

- Fisher, A. (1980). Chattel slavery in the Ottoman empire. Slavery and Abolition, 1(1), 25-45.

- Nikki R., Kiddie (2006). "From the PIous Caliphs Through the Dynastic Caliphates" in Women in the Middle East: past and present. Princeton University Press. pp. 26–48.

- Madeline C. Zilfi Women and slavery in the late Ottoman Empire Cambridge University Press, 2010 p74-75, 115, 186-188, 191-192

- Clarence-Smith, William Gervase., author. (2020). Islam and the abolition of slavery. C Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-78738-338-8. OCLC 1151280156.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "BBC - Religions - Islam: Slavery in Islam". Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- (PDF). 11 January 2012 https://web.archive.org/web/20120111084616/http://www.dlir.org/archive/archive/files/bogazici_1978_vol-6_p149-174_95c6548ada.pdf. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help)CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Janissary - Everything2.com". www.everything2.com.

- "Lewis. Race and Slavery in the Middle East".

- "Schonwalder.com". schonwalder.com. Archived from the original on 2006-10-18. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- "In the Service of the State and Military Class". Archived from the original on 2009-09-11. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- John A. Hostetler: Hutterite Society, Baltimore 1974, page 63.

- Johannes Waldner: Das Klein-Geschichtsbuch der Hutterischen Brüder, Philadelphia, 1947, page 203.

- ""Horrible Traffic in Circassian Women—Infanticide in Turkey," New York Daily Times, August 6, 1856". chnm.gmu.edu.

- "Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nda Kölelik". Archived from the original on February 21, 2006. Retrieved 2007-10-30.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Yermolenko, Galina I. (2010). Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culture. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 111. ISBN 978-1409403746.

- "Avalanche Press". www.avalanchepress.com.

- Adam Glaz; David Danaher; Przemyslaw Lozowski (11 December 2013). The Linguistic Worldview: Ethnolinguistics, Cognition, and Culture. Walter de Gruyter. p. 289. ISBN 978-83-7656-074-8.

- "Slavery – Slave societies". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Brian L. Davies (2014). Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe. pp. 15–26. Routledge.

- For slaves offered as gifts to the sultan and other high-rank officials, see Reindl-Kiel, Hedda. Power and Submission: Gifting at Royal Circumcision Festivals in the Ottoman Empire (16th-18th Centuries). Turcica, Vol.41, 2009, p. 53.

- When Europeans were slaves: Research suggests white slavery was much more common than previously believed Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "BBC - History - British History in depth: British Slaves on the Barbary Coast".

- Milton, G. (2005). White gold: the extraordinary story of Thomas Pellow and Islam's one million white slaves. Macmillan.

- Maddison, A. (2007). Contours of the world economy 1-2030 AD: Essays in macro-economic history. Oxford University Press.

- Khalid, Abdallah (1977). The Liberation of Swahili from European Appropriation. East African Literature Bureau. p. 38. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- Tinker, Keith L. (2012). The African Diaspora to the Bahamas: The Story of the Migration of People of African Descent to the Bahamas. FriesenPress. p. 9. ISBN 978-1460205549.

- Zilfi, Madeline (22 March 2010). Women and Slavery in the Late Ottoman Empire: The Design of Difference. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521515832 – via Google Books.

- Michael N.M., Kappler M. & Gavriel E. (eds.), Ottoman Cyprus, Otto Harrassowitz GmbH & Co., Wiesbaden, 2009, p. 168, 169.

- Lewis, Bernard (1990). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 76. ISBN 978-0195053265.

- Tezcan, Baki (2007). "Politics of early modern Ottoman historiography". In Aksan, Virginia; Goffman, Daniel (eds.). The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0521520850.

- Tezcan, Baki (2007). "Dispelling the Darkness: The Politics of 'Race' in the Early Seventeenth Century Ottoman Empire in the Light of the Life of Mullah Ali". International Journal of Turkish Studies. 13: 75–82.

- Tezcan, Baki (2010). The Second Ottoman Empire: Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9780521519496.

- Artan, Tulay (2015). "The politics of Ottoman imperial palaces: waqfs and architecture from the 16th to the 18th centuries". In Featherstone, Michael; Spieser, Jean-Michel; Tanman, Gulru; Wulf-Rheidt, Ulrike (eds.). The Emperor's House: Palaces from Augustus to the Age of Absolutism. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. p. 378. ISBN 9783110331639.

- Bowering, Gerhard; Crone, Patricia; Kadi, Wadad, eds. (2013). "Racism". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 455.

- "Afro-Turks meet to celebrate Obama inauguration". Today's Zaman. Todayszaman.com. 20 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 February 2009. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- "Esmeray: the untold story of an Afro-Turk music star". The National. thenational.ae. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- Segal, Ronald (2001). Islam's Black Slaves: The History of Africa's Other Black Diaspora. New York: Atlantic Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-1903809815.

- Gordon, Murray (1998). Slavery in the Arab World. New York: New Amsterdam Books. p. 173. ISBN 978-1561310234.

- Doughty, Charles Montagu (1953). Travels in Arabia Deserta. New York: Ltd. Editions Club. pp. vol. I 603, vol. II 250, 289. ISBN 9780844611594.

- Kemball, Arnold (1856). Suppression of the Slave Trade in the Persian Gulf. Bombay: Bombay Education Society Press. p. 649.

- Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The imperial harem : women and sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York. ISBN 0195076737. OCLC 27811454.

- Nikki R., Kiddie (2006). "From the PIous Caliphs Through the Dynastic Caliphates" in Women in the Middle East: past and present. Princeton University Press. pp. 26–48.

- See generally Jay Winik (2007), The Great Upheaval.

- Ayşe Özakbaş, Hürrem Sultan, Tarih Dergisi, Sayı 36, 2000 Archived 2012-01-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Gwyn Campbell, The Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia, 1 edition, (Routledge: 2003), p.ix

- See Winik, supra.

- Henry G. Spooner (1919). The American Journal of Urology and Sexology, Volume 15. The Grafton Press. p. 522. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- Tinker, Keith L. (2012). The African Diaspora to the Bahamas: The Story of the Migration of People of African Descent to the Bahamas. FriesenPress. p. 9. ISBN 978-1460205549.

- Northwestern lancet, Volume 17. s.n. 1897. p. 467. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- John O. Hunwick, Eve Troutt Powell (2002). The African diaspora in the Mediterranean lands of Islam. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-55876-275-6. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- American Medical Association (1898). The Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 30, Issues 1-13. American Medical Association. p. 176. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

the Coptic priests castrate Nubian and Abyssinian slave boys at about 8 years of age and afterward sell them to the Turkish market. Turks in Asia Minor are also partly supplied by Circassian eunuchs. The Coptic priests before.

- Andrews, Walters (2005). The Age of Beloveds: Love and the Beloved in Early-Modern Ottoman and European Culture and Society. Durham and London: Duke University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780822334507.

- Shihade, Magid (2007). "Edmund Burke, III and David N. Yaghoubian, eds. Struggle and Survival in the Modern Middle East, Second Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006. 434 pages, 12 photographs, 1 map, glossary, list of contributors. Paper US$24-95 ISBN 978-0-520-24661-4". Middle East Studies Association Bulletin. 41 (2): 185–186. doi:10.1017/s002631840005063x. ISSN 0026-3184.

- Karamursel, Ceyda. "The Uncertainties of Freedom: The Second Constitutional Era and the End of Slavery in the Late Ottoman Empire". Journal of women's history. 28: 138–161 – via Project Muse Standard Collection.

- "SLAVES SOLD TO THE TURK; HOW THE VILE TRAFFIC IS STILL CARRIED ON IN THE EAST. SIGHTS OUR CORRESPONDENT SAW FOR TWENTY DOLLARS--IN THE HOUSE OF A GRAND OLD TURK OF A DEALER. (Published 1886)". The New York Times. 1886-03-28. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- Wolf Von Schierbrand (March 28, 1886). "Slaves sold to the Turk; How the vile traffic is still carried on in the East. Sights our correspondent saw for twenty dollars--in the house of a grand old Turk of a dealer" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The imperial harem : women and sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York. ISBN 0195076737. OCLC 27811454.

- Madeline C. Zilfi Women and slavery in the late Ottoman Empire Cambridge University Press, 2010

- Walter G., Andrews (2005). The Age of the Beloveds: Love and the Beloved in Early-Modern Ottoman and European Culture and Society. Duke University Press. pp. 1–31.

- Madeline C. Zilfi Women and slavery in the late Ottoman Empire Cambridge University Press, 2010 p74-75, 115, 186-188, 191-192

- Ben-Naeh, Yaron. “Blond, Tall, with Honey-Colored Eyes: Jewish Ownership of Slaves in the Ottoman Empire.” Jewish history 20.3/4 (2006): 315–332. Web.

- Baldwin, James (2012). "Prostitution, Islamic Law and Ottoman Studies". Journal of the economic and social history of the orient. 55: 118–148 – via JSTOR Arts and Scientists VII.

- Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The imperial harem : women and sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York. ISBN 0195076737. OCLC 27811454.

- L.Kurtynova-d'Herlugnan, The Tsar's Abolitionists, Leiden, Brill, 2010

- George Young, Turkey (27 October 2017). "Corps de droit ottoman: recueil des codes, lois, règlements, ordonnances et …". The Clarendon Press – via Internet Archive.

- Badem, C. (2017). The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856). Brill. p353-356

- "Slavery in the Ottoman Empire".

- See also the seminal writing on the subject by Egyptian Ottoman Ahmad Shafiq Pasha, who wrote the highly influential book "L'Esclavage au Point de vue Musulman." ("Slavery from a Muslim Perspective").

- Morgenthau Henry (1918) Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, Garden City, N.Y, Doubleday, Page & Co., chapter 8. Available http://www.gwpda.org/wwi-www/morgenthau/MorgenTC.htm.

- "Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. 1918. Chapter Twenty-Four". www.gwpda.org.

- Eltringham, Nigel; Maclean, Pam (27 June 2014). Remembering Genocide. Routledge. ISBN 9781317754220 – via Google Books.

- Erdem, Y. Hakan (1996). Slavery in the Ottoman Empire and its Demise 1800-1909. MacMillan Press Ltd. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-349-39557-6. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- "Islam and the Abolition of Slavery", C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2006, p.110

.svg.png.webp)