Partus sequitur ventrem

In the history of slavery, the legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem (L. "That which is brought forth follows the belly"; also partus) was used from 1662 in Virginia and later other English royal colonies to establish the legal status of children born there; they were considered to follow the status of their mothers. Therefore, children of enslaved women were born into slavery; those born to free white women (even if indentured servants) were born free.[1] The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem derived from Roman civil law, which concerned personal property (chattels).

.jpg.webp)

In colonial law, the partus doctrine was also used to justify enslavement, as chattels personal, of the native peoples of the Americas and Africa where the Spanish empire (1492–1976), the Portuguese empire (1543–1975), the French colonial empire (1534–1980), and the Dutch empire (1450–1999) established settler colonies to exploit the natural resources of the New World.[2]

As the colonial law in British America (1607–1783), the partus doctrine, passed into law in 1662 in the Virginia colony, established that children were born into the social status of their mother, unlike in English common law, in which the father's status was determinative. Thus de facto and de jure slave status was applied to every child born to an enslaved woman. Other colonies adopted this principle, and it was applied and enforced through the local laws that regulated slavery in the North American colonies (1526–1776).

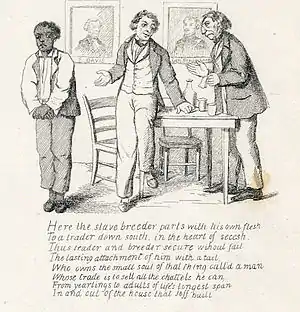

As a function of the political economy of chattel slavery, the legalism of partus sequitur ventrem exempted the biological father from his food-and-shelter obligations, under English common law, toward children he fathered with a slave woman. The denial of paternity to slave children secured the slaveholders' right to profit from exploiting the labour of children engendered, bred, and born into slavery.[3] But it also meant that mixed-race children born to white women were born free. Early generations of families of free people of color in the Upper South were formed from unions between working-class white women and African or African-American men.[4]

History

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Background

In British America (1607–1783), colonists struggled to determine the status of the children of subjects and foreigners. English common law was paternalistic, and determined the legal status (bond or free) of the child of a British subject as based on the legal status of the father as head of family and household, as pater familias. To live in society, a man was legally required to acknowledge his bastard children as well as legal ones, and to support them with food, shelter, and money, and to arrange an apprenticeship so that he or she could become a self-supporting adult.

Regarding chattels (personal property), English common law indicated that the increase and profits generated by chattels (live stock, mobile property) accrued to the owner of said chattels. Beginning in Virginia in 1662, the colonial legislature incorporated that civil law legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem into law in British North America, ruling that the children born in the colonies took the status of their mothers; therefore, children of enslaved mothers were born into slavery as chattel, regardless of the status of their fathers. It was associated with the civil law in Britain, but there the partus legal doctrine did not make chattels of English subjects.[5]

In mid-17th-century Virginia, the mixed-race woman Elizabeth Key Grinstead, then illegally classified as a slave, won her freedom lawsuit (21 July 1656) and formal, legal recognition as a free coloured woman in the thirteen colonies of British North America. Key's successful lawsuit was based upon facts of her birth: her white English father was a member of the House of Burgesses; had acknowledged his paternity of Elizabeth, who was baptized as a Christian in the Church of England; and, before his death, had arranged a guardianship for her, by way of indentured servitude until she came of age. When the man to whom Key was indentured returned to England, he sold her indenture contract to a second man. The latter prolonged Key's servitude beyond the indenture's original term. At the death of the second owner of her indenture, his estate classified Elizabeth Key and her mixed-race son (who also had a white father), as "Negro slaves" who were personal property of the deceased.

Colonial-era legal cases about the rights (human, economic, political) of the mixed-race children of Englishmen and slave women were to determine whether or not a mixed-race person was a British subject. The English colonists were subjects of the Crown, but in England and the colonies, Africans and all non-white foreigners were ineligible to be a British subject. Moreover, British subjecthood also was denied to mixed-race children because they were generally not Christians. They were considered foreigners in a British colony and without legal rights under English common law. As dependencies of the Crown, colonial governments could not legally determine either the subjecthood or the citizenship of the mixed-race children born of a British white man and an enslaved black woman.[3]

British colonial demands for manual labourers required more slaves from Africa to replace the declining number of indentured servants whose contracts had expired. Therefore, in 1662, the Virginia House of Burgesses legislated partus sequitur ventrem to establish that "all children borne in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the [legal] condition of the mother", because enslaved African women and their children were not British subjects.[6] That distinction resulted in enslaved women and their children being classified as the non-white Other, a racial caste of unpaid workers.

After independence from Britain, slave law in the United States continued that distinction. Virginia established a law that no one could be a slave in the state other than those who had that status on October 17, 1785 "and the descendants of the females of them." Kentucky adopted this law in 1798; Mississippi passed a similar law in 1822, using the phrase about females and their descendants; as did Florida in 1828.[7] Louisiana, whose legal system was based on civil law (following its French colonial past), in 1825 added this language to its code: "Children born of a mother then in a state of slavery, whether married or not, follow the condition of their mother."[7] Other states adopted this "norm" through judicial rulings.[7] In summary, the legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem functioned economically to provide a steady supply of slaves.[3]

Mixed-race slaves

By the 18th century, the colonial slave population included mixed-race children of white ancestry, such as mulattoes (half-black), quadroons (quarter-black), and octoroons. They were fathered by white planters, overseers, and other men with power, with enslaved women, who were also sometimes of mixed race.[8]

Numerous mixed-race slaves lived in stable families at the Monticello plantation of Thomas Jefferson. In 1773 his wife, Martha Wayles, inherited more than one hundred slaves from her father John Wayles. These included the six mixed-race children (three-quarters white) whom he fathered with his concubine Betty Hemings, a mulatto born of an Englishman and an enslaved African (black) woman.[9] Martha Wayles's 75 percent-white half-brothers and half-sisters included the much younger Sally Hemings. Later the widower Jefferson took Sally Hemings as a concubine and, over 38 years, had six mixed-race children with her, born into slavery. They were seven-eighths white in ancestry. Four survived to adulthood.[10][11]

Under Virginia law, the Jefferson–Hemings children, seven-eighths European, would have been considered legally white if free. Jefferson allowed the two eldest to "escape", and freed the two youngest in his will. As adults, three of the Jefferson–Hemings children passed into white society: Beverly (male) and Harriet Hemings in the Washington, DC area, and Eston Hemings Jefferson in Wisconsin. He had married a mixed-race woman in Virginia, and both their sons served as regular Union soldiers. The oldest gained the rank of colonel.

Historians had long discounted rumors that Jefferson had this relationship. But in 1998, a Y-DNA test confirmed that a contemporary male descendant of Sally Hemings (through Eston Heming's descendants) was a direct, genetic descendant of the male line of Jeffersons. It was Thomas Jefferson who was documented as having been at Monticello each time Hemings conceived, and the weight of historical evidence favored his paternity.[10]

Mixed-race communities in the Deep South

In the colonial cities on the Gulf of Mexico, New Orleans, Savannah, and Charleston, there arose the Creole peoples as a social class of educated free people of color, descended from white fathers and enslaved black or mixed-race women. As a class, they intermarried, sometimes gained formal education, and owned property, including slaves.[12] Moreover, in the Upper South, some slaveholders freed their slaves after the Revolution through manumission. The population of free black men and free black women rose from less than 1% in 1780 to more than 10% in 1810, when 7.2% of Virginia's population was free black people, and 75% of Delaware's black population were free.[13]

Concerning the sexual hypocrisy related to whites and their sexual abuse of enslaved women, the diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut said:

This only I see: like the patriarchs of old our men live all in one house with their wives and their concubines, the Mulattoes one sees in every family exactly resemble the white children — every lady tells you who is the father of all the Mulatto children in every body's household, but those [Mulatto children] in her own [household], she seems to think drop from the clouds or pretends so to think ...[14]

Likewise, in the Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation in 1838–1839 (1863), Fanny Kemble, the English wife of an American planter, noted the immorality of white slave owners who kept their mixed-race children enslaved.[15]

But some white fathers established common-law marriages with enslaved women. They manumitted the woman and children, or sometimes transferred property to them, arranged apprenticeships and education, and resettled in the North. Some white fathers paid for higher education of their mixed-race children at colour-blind colleges, such as Oberlin College. In 1860 Ohio, at Wilberforce University (est. 1855) owned and operated by the African Methodist Episcopal church, most of the two hundred subscribed students were mixed-race, natural sons of the white men paying their tuition.[16]

See also

References

- Lamb, Gregory M. (January 25, 2005). "The Peculiar Color of Racial Justice". The Christian Science Monitor. The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on August 2, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- M.H.Davidson (1997) Columbus Then and Now, a life re-examined. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 417)

- Lovell Banks, Taunya "Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key's Freedom Suit — Subjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventeenth century Colonial Virginia", 41 Akron Law Review 799 (2008), Digital Commons Law, University of Maryland Law School, accessed 21 April 2009.

- Heinegg, Paul (1995–2005). "Free African Americans in Virginia, North and South Carolina, Delaware and Maryland".

- Morris, Thomas D. (1996). Southern Slavery and the Law, 1619–1860. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-8078-4817-3.

- Kolchin, Peter American Slavery, 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, p. 17.

- Morris, Thomas D. (1996). Southern Slavery and the Law, 1619-1860. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 9780807848173.

- Ellis, Joseph American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (1993) p. 000.

- Davis, Angela (1972). "Reflections on the Black Woman's Role in the Community of Slaves". The Massachusetts Review. 13 (1/2): 81–100. JSTOR 25088201.

- "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account", Monticello Website, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, accessed 22 June 2011. Quote: "Ten years later [referring to their 2000 report], TJF and most historians now believe that, years after his wife's death, Thomas Jefferson was the father of the six children of Sally Hemings mentioned in Jefferson's records, including Beverly, Harriet, Madison and Eston Hemings."

- Helen F.M. Lear, National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Vol. 89, No. 3, September 2001, p. 207

- Kolchin, Peter American Slavery, 1619–1865, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, pp. 82–83.

- Kolchin, American Slavery, p. 81.

- Jackson, Ed; Pou, Charles. "1861: This Day in Georgia History". University of Georgia. Archived from the original on December 1, 2005.

- Fanny Kemble (1863). Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation in 1838–1839. Harper & Brothers. Retrieved December 20, 2009 – via Internet Archive.

Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation in 1838–1839

- Campbell, James T. (1995). Songs of Zion. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 259–260. ISBN 9780195360059. Retrieved January 13, 2009.