Spice Girls

The Spice Girls are an English pop girl group formed in 1994. The group comprises Melanie Brown, also known as Mel B ("Scary Spice"), Melanie Chisholm, Mel C ("Sporty Spice"), Emma Bunton ("Baby Spice"), Geri Halliwell ("Ginger Spice"), and Victoria Beckham née Adams ("Posh Spice"). In 1996, Top of the Pops magazine gave each member of the group aliases, which were adopted by the group and media. With their "girl power" mantra, the Spice Girls were pop culture icons of the 1990s.[1][2] Time called them "arguably the most recognizable face" of Cool Britannia, the mid-1990s celebration of youth culture in the UK.[3] They are cited as part of the Second British Invasion of the US.[4]

Spice Girls | |

|---|---|

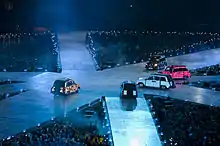

The Spice Girls performing during their penultimate reunion concert in Toronto, Ontario, in February 2008. (L–R) Melanie C., Victoria Beckham, Geri Halliwell, Melanie B. and Emma Bunton | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | London, England |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1994–2001, 2007–2008, 2012, 2016, 2018–present |

| Labels | Virgin |

| Website | thespicegirls |

| Members | |

| Past members | |

The Spice Girls were signed to Virgin Records and released their debut single "Wannabe" in 1996; it hit number one in 37 countries[5][6] and commenced their global success. Their debut album Spice (1996) sold more than 23 million copies worldwide, becoming the best-selling album by a female group in history.[7] Their follow-up album, Spiceworld (1997), was also a commercial success, selling over 13 million copies worldwide.[8] In November 2000, the group released Forever, which was their only album without Halliwell. In January 2001, the group unofficially announced that they were beginning an indefinite hiatus and would be concentrating on their solo careers in regard to their foreseeable future, although they pointed out that the group were not splitting.

Measures of the Spice Girls' success include international record sales, vast merchandising enterprises, iconic symbolism such as Halliwell's Union Jack dress representing "girl power", a film, Spice World (1997), and two reunion tours, 2007–2008 and 2019. Under the guidance of their mentor and manager Simon Fuller, the group embraced merchandising and became a regular feature of the British and global press. The group became one of the most successful marketing engines ever,[9] earning up to $75 million per year,[10] with their global gross income estimated at $500–800 million by May 1998.[9]

The Spice Girls have sold 85 million records worldwide, making them the best-selling girl group of all time, one of the best-selling artists, and the biggest British pop success since the Beatles.[11][12][13] The group have received a number of awards including five Brit Awards, three American Music Awards, four Billboard Music Awards, three MTV Europe Music Awards, one MTV Video Music Award and three World Music Awards. In 2000, they received the Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to British Music. According to Rolling Stone journalist and biographer David Sinclair, "Scary, Baby, Ginger, Posh, and Sporty were the most widely recognised group of individuals since John, Paul, George, and Ringo".[14]

Band history

1994–1996: Formation and early years

– Advertisement placed in The Stage

In the mid-1990s, relatives Bob and Chris Herbert of Heart Management decided to create a girl group to compete with popular boy bands, such as Take That and East 17, which dominated the pop music scene at the time.[16] In February 1994, together with financier Chic Murphy, they placed an advertisement in the trade magazine The Stage asking for singers to audition for an all-female pop band at Danceworks studios.[16] Approximately 400 women attended the audition, during which they were placed in groups of 10 and danced a routine to "Stay" by Eternal, followed by solo auditions in which they were asked to perform songs of their own choosing. After several weeks of deliberation, Victoria Adams, Melanie Brown, Melanie Chisholm and Michelle Stephenson were among 12 women chosen to a second round of auditions in April; Geri Halliwell also attended the second audition, despite missing the first.[16]

A week after the second audition, the women were asked to attend a recall at Nomis Studios in Shepherds Bush, performing "Signed, Sealed, Delivered" on their own and in a group. During the session, Adams, Brown, Chisholm, Halliwell and Stephenson were selected for a band initially named "Touch".[16] The group moved to a house in Maidenhead, Berkshire, and spent most of 1994 practising songs which had been written for them by Bob Herbert's long-time associates John Thirkell and Erwin Keiles.[17] During the first two months, they worked on demos at South Hill Park Recording Studios in Bracknell with producer/studio owner Michael Sparkes and songwriter/arranger Tim Hawes. According to Stephenson, the material the group was given was "very, very young pop";[18] one of the songs they recorded, "Sugar and Spice", would be the source of their final band name. They also worked on various dance routines at the Trinity Studios in Knaphill, near Woking, Surrey. A few months into the training period, Stephenson was fired from the group and replaced with Emma Bunton.[19] It was also during this time that Halliwell came up with the band name Spice.[16]

The group felt insecure about the lack of a contract and was frustrated by the direction in which Heart Management was steering them. In October 1994, armed with a catalogue of demos and dance routines, they began touring management agencies. They persuaded Bob Herbert to set up a showcase performance for the group in front of industry writers, producers and A&R men in December 1994 at the Nomis Studios, where they received an "overwhelmingly positive" reaction.[20] Due to the large interest in the group, the Herberts quickly set about creating a binding contract for them. Encouraged by the reaction they had received at the Nomis showcase, all five members delayed signing contracts on legal advice from, among others, Adams's father.[21]

In March 1995, the group parted from Heart Management due to their frustration with the company's unwillingness to listen to their visions and ideas. To ensure they kept control of their own work, they allegedly stole the master recordings of their discography from the management offices.[21][22] That same day, the group tracked down Sheffield-based producer Eliot Kennedy, who had been present at the showcase, and persuaded him to work with them. They were introduced to record producers Absolute, who in turn brought them to the attention of Simon Fuller of 19 Entertainment, who signed them to his company in March 1995. During the summer of that year, the group toured record labels in London and Los Angeles with Fuller, signing a deal with Virgin Records in September 1995. Their name was changed to Spice Girls, as a rapper was already using the name "Spice".[16] From this point on until the summer of 1996, the group continued to write and record tracks for their debut album while extensively touring the west coast of the US, where they signed a publishing deal with Windswept Pacific.[21]

1996–1997: Spice and breakthrough

On 7 July 1996, the Spice Girls released their debut single "Wannabe" in the United Kingdom. In the weeks leading up to the release, the music video for "Wannabe" (directed by Swedish commercials director Johan Camitz and shot in April at the entrance and main staircase of the St. Pancras Grand Hotel in London), got a trial airing on music channel The Box.[23] The video was an instant hit, and was aired up to seventy times a week at its peak. After the video was released, the Spice Girls had their first live TV slot on broadcast on LWT's Surprise Surprise. The first music press interview appeared in Music Week. In July 1996, the group conducted their first interview with Paul Gorman, the contributing editor of music paper Music Week, at Virgin Records' Paris headquarters. His piece recognised that the Spice Girls were about to institute a change in the charts away from Britpop and towards out-and-out pop. He wrote: "JUST WHEN BOYS with guitars threaten to rule pop life—Damon's all over Smash Hits, Ash are big in Big! and Liam can't move for tabloid frenzy—an all-girl, in-yer-face pop group have arrived with enough sass to burst that rockist bubble."[24] The song entered the UK Singles Chart at number three before moving up to number one the following week and staying there for seven weeks. The song proved to be a global hit, hitting number one in 37 countries, including four consecutive weeks atop the Billboard Hot 100 in the US, and becoming not only the biggest-selling debut single by an all-female group but also the biggest-selling single by an all-female group of all time.[5][25][26]

Riding a wave of publicity and hype, the group released their next singles in the UK and Europe; in October "Say You'll Be There" was released topping the charts at number one for two weeks. In December "2 Become 1" was released, becoming their first Christmas number one and selling 462,000 copies in its first week,[27] making it the fastest-selling single of the year. The two tracks continued the group's remarkable sales, giving them three of the top five biggest-selling songs of 1996 in the UK.[28] In November 1996, the Spice Girls released their debut album Spice in Europe. The success was unprecedented and drew comparisons to Beatlemania,[13] leading the press to dub it "Spice mania"[29][30][31][32] and the group the "Fab Five".[33][34][35][36] In seven weeks Spice had sold 1.8 million copies in Britain alone,[37] making the Spice Girls the fastest-selling British act since the Beatles. In total, the album sold over 3 million copies in Britain,[37] the biggest-selling album of all time in the UK by a female group,[38] certified 10× Platinum,[37] and peaked at number one for fifteen non-consecutive weeks.[39] In Europe the album became the biggest-selling album of 1997 and was certified 8× Platinum by the IFPI for sales in excess of 8 million copies.[40]

That same month the Spice Girls attracted a crowd of 500,000 when they switched on the Christmas lights in Oxford Street, London.[16] At the same time, Simon Fuller started to set up million pound sponsorship deals for the Spice Girls with Pepsi, Walkers, Impulse, Cadbury's and Polaroid.[16] In December 1996, the group won three trophies at the Smash Hits awards at the London Arena, including best video for "Say You'll Be There".[16] In January 1997, the group released "Wannabe" in the United States.[41] The single, written by the Spice Girls, Richard Stannard and Matt Rowe also proved to be a catalyst in helping the Spice Girls break into the notoriously difficult US market when it debuted on the Hot 100 Chart at number eleven. At the time, this was the highest-ever debut by a non-American act, beating the previous record held by the Beatles for "I Want to Hold Your Hand" and the joint highest entry for a debut act beating Alanis Morissette with "Ironic".[16] "Wannabe" reached number one in the US for four weeks. In February 1997, Spice was released in the US, and became the biggest-selling album of 1997 in the US, peaking at number one, and was certified 7× Platinum by the RIAA[42] for sales in excess of 7.4 million copies.[43] The album is also included in the Top 100 Albums of All Time list of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) based on US sales.[44] In total, the album sold over 23 million copies worldwide becoming the biggest-selling album in pop music history by an all-female group.[7]

– Harper's Bazaar on Geri Halliwell’s Union Jack dress at the 1997 Brit Awards.[45]

Later that month, the Spice Girls won two Brit Awards for Best British Video, "Say You'll Be There" and Best British Single for "Wannabe".[16][46] The group performed "Who Do You Think You Are" to open the 1997 Brit Awards, with Geri Halliwell wearing a Union Jack mini-dress that became one of pop history's most famed outfits.[15][47] In March 1997, a double A-side of "Mama"/"Who Do You Think You Are" was released in Europe, the last from Spice, which once again saw them at number one,[48] making the Spice Girls the first group in history since the Jackson 5 to have four consecutive number one hits.[16] Girl Power!, The Spice Girls' first book and manifesto was launched later that month at the Virgin Megastore. It sold out its initial print run of 200,000 copies within a day, and was eventually translated into more than 20 languages. In April, One Hour of Girl Power was released; it sold 500,000 copies in the UK between April and June to become the best-selling pop video ever.[49][50] In May, Spice World was announced by the Spice Girls at the Cannes Film Festival. The group also performed their first live British show, for the Royalty of Great Britain. At the show, they breached royal protocol when Mel B and then Geri Halliwell planted kisses on Prince Charles' cheeks and pinched his bottom, causing controversy.[16] At the Ivor Novello Awards, the group won International Hit of the Year and Best-Selling British Single awards for "Wannabe". In June 1997, Spice World began filming and wrapped in August. In September, the Spice Girls performed "Say You'll Be There" at the 1997 MTV Video Music Awards at Radio City Music Hall in New York City, and won Best Dance Video for "Wannabe".[51] The MTV Awards came five days after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, with tributes paid to her throughout the ceremony. Mel C stated, "We'd like to dedicate this award to Princess Diana, who is a great loss to our country."[52] At the 1997 Billboard Music Awards the group won four awards; New Artist of the Year, Billboard Hot 100 Singles Group of the Year, Billboard 200 Group of the Year and Billboard 200 Album of the Year for Spice.[53]

1997–1998: Groundbreaking success, Spiceworld and Halliwell's departure

In October 1997, the Spice Girls released the first single from Spiceworld, "Spice Up Your Life". It entered the UK Singles Chart at number one, making it the group's fifth consecutive number-one single.[54] That same month, the group performed their first live major concert to 40,000 fans in Istanbul, Turkey.[55] Later, they launched The Royal British Legion's Poppy Appeal,[56] then travelled to South Africa to meet Nelson Mandela, who announced, "These are my heroes."[57] In November, the Spice Girls released their second album, Spiceworld. It set a new record for the fastest-selling album when it shipped seven million copies over the course of two weeks. Gaining favourable reviews,[58] the album went on to sell over 10 million copies in Europe,[59] Canada,[60] and the United States[42] combined, and 13 million copies worldwide.[8] Criticised in the United States for releasing the album just nine months after their debut there, which gave the group two simultaneous Top 10 albums in the Billboard album charts,[61] and suffering from over-exposure at home,[56] the Spice Girls began to experience a media backlash. The group was criticised for the number of sponsorship deals signed—over twenty in total—and they began to witness diminishing international chart positions.[62] Nevertheless, the Spice Girls remained the biggest-selling pop group of both 1997 and 1998.[21]

On 7 November 1997, the group performed "Spice Up Your Life" in the 1997 MTV Europe Music Awards, and won the Best Group award.[63] After this performance, the Spice Girls made the decision to take over the running of the group themselves, and fired their manager Simon Fuller.[5] The firing was front-page news around the world. Many commentators speculated that Fuller had been the true mastermind behind the group, and that this was the moment when the band lost their impetus and direction.[64][65] Later that month, the Spice Girls became the first pop group to host ITV's An Audience with...;[66] their show was watched by 11.8 million viewers in the UK, one fifth of the population.[67] In December 1997, the second single from Spiceworld, "Too Much", was released, becoming the group's second Christmas number one and their sixth consecutive number-one single in the UK. The group ended 1997 as the year's most played artist on American radio.[68] At the 1998 American Music Awards on 26 January, the Spice Girls won the awards for Favorite Pop Album, Favorite New Artist and Favorite Pop Group.[69] In February 1998, they won a special award for overseas success at the 1998 Brit Awards, with combined sales of albums and singles for over of 45 million records worldwide.[70][71] That night, the group performed their next single, "Stop", their first not to reach number one in United Kingdom, entering at number two.[54]

In early 1998, the Spice Girls embarked on the Spiceworld Tour covering Europe and North America, starting in Dublin, Ireland on 24 February 1998 before moving to mainland Europe, and then returning to the United Kingdom for two gigs at Wembley Arena.[72] Later that year, the Spice Girls were invited to sing on the official England World Cup song "How Does It Feel (To Be on Top of the World)", the last song recorded with Halliwell until 2007. On 31 May 1998, Halliwell announced her departure from the Spice Girls through her solicitor.[73] Halliwell claimed that she was suffering from exhaustion and wanted to take a break. Rumours of a power struggle with Brown as the reason for her departure were circulated by the press.[10][74] Halliwell's departure from the group shocked fans and became one of the biggest entertainment news stories of the year, making news headlines the world over.[75] The four remaining members were adamant that the group would carry on.[73]

Halliwell's departure was the subject of a lawsuit by Aprilia World Service B.V. (AWS), a manufacturer of motorcycles and scooters. On 9 March 1998, Halliwell informed the other members of the group of her intention to withdraw from the group, yet the girls signed an agreement with AWS on 24 March and again on 30 April and participated in a commercial photo shoot on 4 May in Milan, eventually concluding a contract with AWS on 6 May 1998. The Court of Appeal of England and Wales held that their conduct constituted a misrepresentation by giving the impression that Halliwell intended to remain part of the group in the foreseeable future, allowing AWS to rescind their contract with the Spice Girls. This is now the leading case in English law on misrepresentation by conduct.[76][77]

"Viva Forever" was the last single released from Spiceworld. The video for the single was made before Halliwell's departure and features the girls in stop-motion animated form. The North American tour began in West Palm Beach on 15 June, and grossed $60 million over 40 sold-out performances.[10]

1998–2000: Forever and hiatus

While on tour in the United States, the group continued to record new material and released a new song, "Goodbye", before Christmas in 1998. The song was seen as a tribute to Geri Halliwell, and when it topped the UK Singles Chart it became their third consecutive Christmas number one—equalling the record previously set by the Beatles.[78] Later in 1998, Bunton and Chisholm appeared at the 1998 MTV Europe Music Awards without their other band members, and the group won two awards: "Best Pop Act" and "Best Group" for a second time.[79] In late 1998, Brown and Adams announced they were both pregnant; Brown was married to dancer Jimmy Gulzer and became known as Mel G for a brief period. She gave birth to daughter Phoenix Chi in February 1999.[80] One month later, Adams gave birth to son Brooklyn, whose father was then Manchester United footballer David Beckham. Later that year, she married Beckham in a highly publicised wedding in Ireland.[81]

The Spice Girls returned to the studio in August 1999, after an eight-month recording break to start work on their third and last studio album. The album's sound was initially more pop-influenced, similar to their first two albums, and included production from Eliot Kennedy.[82] The album's sound took a mature direction when American producers like Rodney Jerkins, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis came on to collaborate with the group. In December 1999 they performed live for a UK-only tour, Christmas in Spiceworld, in London and Manchester, also showcasing new songs from the third album.[83] During 1999, the group recorded the character Amneris' song "My Strongest Suit" in Elton John's and Tim Rice's Aida, a concept album which would later go on to fuel the musical version of Verdi's Aida. The band performed again at the 2000 Brit Awards, where they received a Lifetime Achievement Award. Despite being at the event, Halliwell did not join her former bandmates on stage.[84] In November 2000, the group released Forever. Sporting a new edgier R&B sound, the album received a lukewarm response from critics.[85]

In the US, the album peaked at number thirty-nine on the Billboard 200 albums chart. In the UK, the album was released the same week as Westlife's Coast to Coast album and the chart battle was widely reported by the media, where Westlife won the battle reaching number one in the UK, leaving the Spice Girls at number two.[86] The lead single from Forever, the double A-side "Holler"/"Let Love Lead the Way", became the group's ninth number one single in the UK.[87] However, the song failed to break onto the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart stateside, instead peaking at number seven on the Bubbling Under Hot 100 Singles. "Holler" did peak at number thirty-one on the Hot Dance Music/Club Play chart in 2000. The only major performance of the lead single came at the MTV Europe Music Awards on 16 November 2000.[88] In total, Forever achieved only a fraction of the success of its two best-selling predecessors, selling five million copies.[89] In January 2001, the group unofficially announced that they were beginning an indefinite hiatus and would be concentrating on their solo careers in regard to their foreseeable future, although they pointed out that the group was not splitting.[90][91]

2007–2008: Return of the Spice Girls and Greatest Hits

On 28 June 2007, the group held a press conference at The O2 Arena revealing their intention to reunite.[92] The plan to re-form had long been speculated by the media,[93] but the group finally confirmed their intention to embark upon a worldwide concert tour, starting in Vancouver on 2 December 2007.[94] Filmmaker Bob Smeaton directed an official documentary on the reunion. It was entitled Spice Girls: Giving You Everything and was first aired on Australia's Fox8 on 16 December 2007,[95] followed by BBC One in the UK, on 31 December.[96] Ticket sales for the first London date of the Return of the Spice Girls tour sold out in 38 seconds.[97] It was reported that over one million people signed up in the UK alone and over five million worldwide for the ticket ballot on the band's official website.[97] Sixteen additional dates in London were added,[98] all selling out within one minute.[99] In the United States, Las Vegas, Los Angeles and San Jose shows also sold out, prompting additional dates to be added.[100] It was announced that the Spice Girls would be playing dates in Chicago and Detroit and Boston, as well as additional dates in New York to keep up with the demand. On the first concert in Canada, they performed to an audience of 15,000 people, singing twenty songs and changing a total of eight times.[101] Along with the tour sellout, the Spice Girls licensed their name and image to Tesco's UK supermarket chain.[102]

The group's comeback single, "Headlines (Friendship Never Ends)", was announced as the official Children in Need charity single for 2007 and was released 5 November. The first public appearance on stage by the Spice Girls occurred at the Victoria's Secret Fashion Show, where they performed two songs, 1998 single "Stop" and the lead single from their greatest hits album, "Headlines (Friendship Never Ends)". The show was filmed by CBS on 15 November 2007 for broadcast on 4 December 2007.[103] They also performed both songs live for the BBC Children in Need telethon on 16 November 2007 from Los Angeles. The release of "Headlines (Friendship Never Ends)" peaked at number eleven on the UK Singles Chart, making it the group's lowest-charting British single to date. The album peaked at number two on the UK Albums Chart. On 1 February 2008, it was announced that due to personal and family commitments their tour would come to an end in Toronto on 26 February 2008, meaning that tour dates in Beijing, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Sydney, Cape Town and Buenos Aires were cancelled.[104] Overall, the tour produced some $107.2 million in ticket sales and merchandising, with sponsorship and ad deals bringing the total to $200 million.[105] In March 2008, the group won the coveted "Icon Awards" at the 95.8 Capital Awards; Bunton and Chisholm collected the award. In June, they captured the Glamour Award for the Best Band; Bunton, Brown and Halliwell received the award at the event. In September, the Spice Girls won the "Best Live Return Award" at the 2008 Live Vodafone Music Awards, beating acts such as Led Zeppelin and the Sex Pistols. Bunton was there to collect the award.[106]

2010–2012: Viva Forever musical and London Olympics

In 2010, the group was nominated for a Brit Award in the new category, "Best Performance of the 30th Year" for their 1997 Brit Awards performance of their songs, "Wannabe" and "Who Do You Think You Are". The group later won the award which was received by Halliwell and Brown. The group along with Simon Fuller also teamed with Judy Craymer and Jennifer Saunders to develop a Spice Girls musical, Viva Forever!. Although the group were not in the musical, they influenced the show's cast and production choices in a story which uses the music, similar to ABBA's music in Mamma Mia!.[107]

Two years later, in June 2012, the group reunited for the first time in four years for the press conference in London to promote the launch of Viva Forever!.[108] The press conference was held at St. Pancras Renaissance London Hotel, the location where the group filmed the music video for "Wannabe", sixteen years earlier, to the day.[109] In August 2012, after much speculation and anticipation from the press and the public, the group performed a medley of "Wannabe" and "Spice Up Your Life" at the 2012 Summer Olympics closing ceremony, reuniting solely for the event.[110][111] Their performance received great response from critics and audiences and became the most tweeted moment of the entire Olympics with over 116,000 tweets on Twitter per minute.[112] In December 2012, the group reunited once again for the premiere of Viva Forever! at the West End's Piccadilly Theatre.[113] In addition to the promotion of the musical, the group appeared in the documentary, Spice Girls' Story: Viva Forever! which aired on 24 December 2012 on ITV1.[114]

2016–present: Second reunion

On 8 July 2016, Brown, Bunton and Halliwell released a video celebrating the 20th anniversary of their first single "Wannabe", alongside a website under the name "The Spice Girls - GEM" and teased news from them as a three-piece.[115] Brown later clarified that "GEM" was not a new name for the three-piece but rather simply the name of the website.[116] Beckham and Chisholm opted not to take part in a reunion project, with Brown reaffirming their positions in saying, "Victoria's busy [...] Mel C's doing her own album" and noted that both members gave the three-piece their blessing to continue with the project.[117] On 23 November 2016, a new song, "Song for Her", was leaked online.[118] Following Halliwell's announcement of her pregnancy, the project was cancelled.[119]

.jpg.webp)

On 5 November 2018, Brown, Bunton, Chisholm and Halliwell announced a tour for 2019. Beckham declined to join due to commitments regarding her fashion business.[120][121] The Spice World – 2019 Tour commenced at Croke Park in Dublin, Ireland on 24 May 2019.[122] A 13 date European tour, it concluded with three concerts at London's Wembley Stadium, with the last taking place on 15 June 2019.[123] The tour produced 700,000 spectators and earned $78.2 million.[124][125] Despite sound problems in the early concerts, Anna Nicholson in The Guardian writes, "As nostalgia tours go, this could hardly have been bettered. Victoria's dry wit was missed, but some passive-aggressive patter and a food fight is how you really sell a tour."[126]

On 30 April 2019, the group teamed up with the children's book franchise Mr. Men, in order to create many derivative products such as books, cups, bags and coasters.[127][128][129] On 13 June 2019, it was reported that Paramount Animation president Mireille Soria had green lit an animated film based on the group, with all five members returning. The project will be produced by Simon Fuller, with Karen McCullah and Kirsten Smith writing the screenplay, and will feature both previous and original songs.[130] The film will feature the band as superheroes. A director has not yet been announced.[131]

Cultural impact and legacy

Pop music scene

The Spice Girls broke onto the music scene at a time when alternative rock, hip-hop and R&B dominated global music charts. The modern pop phenomenon that the Spice Girls created by targeting early members of Generation Y was credited with changing the global music landscape,[132][133][134] bringing about the global wave of late-1990s and early-2000s teen pop acts such as Hanson, Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera and NSYNC.[135][136][137][138]

The Spice Girls have also been credited with paving the way for the girl groups and female pop singers that have come after them.[139][140][141] In the UK, they are credited for their massive commercial breakthrough in the previously male-dominated pop music scene,[141][142] leading to the widespread formation of new girl groups in the late 1990s and early 2000s including All Saints, B*Witched, Atomic Kitten, Girls Aloud and Sugababes, hoping to emulate the Spice Girls' success.[143][144][145] Twenty-first-century girl groups, including the Pussycat Dolls,[146] 2NE1,[147] Girls' Generation,[148] Little Mix[149][150] and Fifth Harmony,[151] continue to cite the group as a major source of influence, as have female singers, including Lady Gaga,[152] Jess Glynne,[153] Alexandra Burke,[153] Kim Petras,[154] Charli XCX,[155][156] Rita Ora,[157] Demi Lovato[158] and Carly Rae Jepsen.[159] During her 2005 "Reflections" concert series, Filipina superstar Regine Velasquez performed a medley of Spice Girls songs consisting of "Wannabe", "Say You'll Be There", "2 Become 1", "Who Do You Think You Are" and "Holler", as a tribute to the band she says were a major influence on her music.[160] Danish singer-songwriter MØ decided to pursue music after watching the Spice Girls on TV as a child, saying in a 2014 interview: "I have them and only them to thank—or to blame—for becoming a singer."[161] 15-time Grammy Award-winning singer-songwriter Adele credits the Spice Girls as a major influence in regard to her love and passion for music, stating that "they made me what I am today".[162][163]

Girl power

The phrase "girl power" put a name to a social phenomenon, but the slogan was met with mixed reactions.[164] The phrase was a label for the particular facet of post classical neo-feminist empowerment embraced by the band: that a sensual, feminine appearance and equality between the sexes need not be mutually exclusive. This concept was by no means original in the pop world: both Madonna and Bananarama had employed similar outlooks. The phrase itself had also appeared in a few songs by British girl groups and bands since at least 1987; most notably, it was the name of British pop duo Shampoo's 1996 single and album, later credited by Halliwell as the inspiration for the Spice Girls' mantra.[22][165] In a Christmas 1996 interview with The Spectator magazine, Halliwell spoke of former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher as being an inspiration for the group: "We are true Thatcherites. Thatcher was the first Spice Girl, the pioneer of our ideology."[166]

However, it was not until the emergence of the Spice Girls in 1996 with "Wannabe", that the concept of "girl power" exploded onto the common consciousness.[167] The phrase was regularly uttered by all five members—although most closely associated with Halliwell—and was often delivered with a peace sign.[168] The slogan also featured on official Spice Girls merchandise and on some of the outfits the group members wore. The Spice Girls' version was distinctive. Its message of empowerment appealed to young girls, adolescents and adult women,[169][164] and it emphasised the importance of strong and loyal friendship among females.[170][171] According to Billboard magazine, they demonstrated real, noncompetitive female friendship, singing: "If you wannabe my lover, you gotta get with my friends. Make it last forever; friendship never ends."[167]

In all, the focused, consistent presentation of "girl power" formed the centrepiece of their appeal as a band.[164][172] Some commentators credit the Spice Girls with reinvigorating mainstream feminism—popularised as "girl power"—in the 1990s,[173][174] with their mantra serving as a gateway to feminism for their young fans.[171][175] On the other hand, some critics dismissed it as no more than a shallow marketing tactic, while others took issue with the emphasis on physical appearance, concerned about the potential impact on self-conscious and/or impressionable youngsters.[169] Regardless, the phrase became a cultural phenomenon,[176] adopted as the mantra for millions of girls[164][171] and even making it into the Oxford English Dictionary.[177] In summation of the concept, author Ryan Dawson said, "The Spice Girls changed British culture enough for Girl Power to now seem completely unremarkable."[13]

The Spice Girls' debut single "Wannabe" has been hailed as an "iconic girl power anthem".[133][178][179] In 2016, the United Nations' Global Goals "#WhatIReallyReallyWant" campaign filmed a global remake of the original music video for "Wannabe" to highlight gender inequality issues faced by women across the world. The video, which was launched on YouTube and ran in movie theatres internationally,[180] featured British girl group M.O, Canadian "viral sensation" Taylor Hatala, Nigerian-British singer Seyi Shay and Bollywood actress Jacqueline Fernandez lip-syncing to the song in various locations around the world.[181] In response to the remake, Beckham said, "How fabulous is it that after 20 years the legacy of the Spice Girls' girl power is being used to encourage and empower a whole new generation?"[180]

At the 43rd People's Choice Awards in January 2017, American actress Blake Lively dedicated her "Favorite Dramatic Movie Actress" award to "girl power" in her acceptance speech, and credited the Spice Girls, saying: "What was so neat about them was that they're all so distinctly different, and they were women, and they owned who they were, and that was my first introduction into girl power."[182] In 2018, Rolling Stone named the Spice Girls' girl power on The Millennial 100, a list of 100 people, music, cultural touchstones and movements that have shaped a generation (those born between 1980 and 1995).[183]

Cool Britannia

The term "Cool Britannia" became prominent in the media and represented the new political and social climate that was emerging with the advances made by New Labour and the new UK Prime Minister Tony Blair. Coming out of a period of 18 years of Conservative government, Tony Blair and New Labour were seen as young, cool and appealing, a driving force in giving Britain a feeling of euphoria and optimism.[184]

Although by no means responsible for the onset of "Cool Britannia", the arrival of the Spice Girls added to the new image and re-branding of Britain, and underlined the growing world popularity of British, rather than American, pop music. This fact was underlined at the 1997 Brit Awards; the group won two awards[185] but it was Halliwell's iconic red, white and blue Union Jack mini-dress that appeared in media coverage around the world, becoming an enduring image of "Cool Britannia".[47][186] In 2016, Time acknowledged the Spice Girls as "arguably the most recognisable face" of "Cool Britannia".[3]

Fashion trends, image and nicknames

The Spice Girls are considered style icons of the 1990s; their image and styles becoming inextricably tied to the band's identity.[187][188][189] They are credited with setting 1990s fashion trends such as Buffalo platform shoes[190] and double bun hairstyles.[191][192] The group have also been noted for the memorable outfits they have worn, the most iconic being Halliwell's Union Jack dress from the 1997 Brit Awards.[193] The dress was sold at a charity auction to the Las Vegas Hard Rock Cafe for £41,320, giving Halliwell the Guinness World Record at that time for the most expensive piece of pop star clothing ever sold.[194][195] Their style has inspired other celebrities including Katy Perry,[196] Charli XCX,[197] Billie Eilish,[198] and Bollywood actress Anushka Ranjan.[199]

The Spice Girls' image was deliberately aimed at young girls, an audience of formidable size and potential. Instrumental to their range of appeal within the target demographic were the bandmates' five divergent personalities and styles, which encouraged fans to identify with one member or another and were a departure from previous bands.[169][200] This marketing of each member's individuality was reinforced by the distinctive nicknames adopted by each member of the group. Their concept of each band member having a distinct style identity has been influential to later teen pop groups such as boy band One Direction.[201][202]

Shortly after "Wannabe"'s release, a lunch with Peter Loraine, then-editor of Top of the Pops, inadvertently led the Spice Girls to adopt the nicknames that ultimately played a key role in their marketability and the way their international audience identified with them. After the lunch, Loraine and his editorial staff decided to devise nicknames for each member of the group based on their personalities. In an interview with Music Week, Loraine explained that, "In the magazine we used silly language and came up with nicknames all the time so it came naturally to give them names that would be used by the magazine and its readers; it was never meant to be adopted globally." Shortly after using the nicknames in a magazine feature on the group, Loraine received calls from other British media outlets requesting permission to use them, and before long the nicknames were synonymous with the Spice Girls.[203]

Each Spice Girl had a unique, over-the-top style that served as an extension of her public persona, becoming her trademark look.[187][204]

- Victoria Beckham: Beckham was called Posh Spice because of her more upper-middle-class background, her choppy brunette bob cut and refined attitude, signature pout, form-fitting designer outfits (often a little black dress) and her love of high-heeled footwear.[187][205]

- Melanie Brown: Brown (also called Mel B) was given the nickname Scary Spice and was known for her "in-your-face" attitude,[206] "loud" Leeds accent,[207] pierced tongue[207] and bold manner of dress (which often consisted of leopard-print outfits).[187]

- Emma Bunton: Bunton was called Baby Spice because she was the youngest member of the group, wore her long blonde hair in pigtails, wore pastel (particularly pink) babydoll dresses and platform sneakers, had an innocent smile, and had a girly girl personality.[187][208]

- Melanie Chisholm: Chisholm (also called Mel C) was called Sporty Spice because she usually wore a tracksuit paired with athletic shoes, wore her long dark hair in a high ponytail, and sported a tough-girl attitude as well as tattoos on both of her arms. She also possessed true athletic abilities, her signature being her ability to perform back handsprings.[187][209]

- Geri Halliwell: Halliwell was called Ginger Spice because of her "liveliness, zest and flaming red hair." Her image centred on "glammed-up sex appeal", and she often wore sultry and outrageous stage outfits, as in the iconic Union Jack dress.[187] The eldest member of the group, Halliwell was seen as the de facto leader of the group thanks to her articulate conversational style and business savvy nature.[210][211]

In their one-off reunion at the 2012 Summer Olympics closing ceremony, the Spice Girls performed in updated high fashion versions of their signature outfits,[111] after entering the Olympic Stadium in five black cabs which lit up with LEDs and laser beams, each decorated with their individual trademark emblems (Posh: sparkling black, Sporty: racing stripes, Scary: leopard print, Baby: pink and Ginger: the Union Jack).[212]

Commercialisation and celebrity culture

At the height of "Spice mania", the group were involved in a prolific marketing phenomenon.[213][214][215][216] Under the guidance of their mentor and manager Simon Fuller, they advertised for an unprecedented number of brands, becoming the most merchandised group in music history,[165][217] and were a frequent feature of the global press.[215][218]

According to Rolling Stone's David Sinclair, "So great was the daily bombardment of Spice images and Spice product that it quickly became oppressive even to people who were well disposed towards the group."[219] This was even parodied in the video for their song "Spice Up Your Life", which depicts the group going around a futuristic dystopian city in a space ship surrounded by billboards and adverts featuring them. Throughout the American leg of their 1998 Spiceworld world tour, commercials were played on large concert screens before the shows and during intermissions. It was the first time advertising had been used in pop concerts and was met with mixed reactions in the music industry. Nevertheless, it opened up a whole new concert revenue stream, with music industry pundits predicting more acts would follow the Spice Girls' lead.[220][221]

In his analysis of the group's influence on 21st-century popular culture two decades after their debut, John Mckie of the BBC noted that while other stars had used brand endorsements in the past, "the Spice brand was the first to propel the success of the band".[169] The Guardian's Sylvia Patterson also wrote of what she called the Spice Girls' true legacy: "[T]hey were the original pioneers of the band as brand, of pop as a ruthless marketing ruse, of the merchandising and sponsorship deals that have dominated commercial pop ever since."[137]

The mainstream media embraced the Spice Girls at the peak of their success. The group received regular international press coverage and were constantly followed by paparazzi.[222] Paul Gorman of Music Week said of the media interest in the Spice Girls in the late 1990s: "They inaugurated the era of cheesy celebrity obsession which pertains today. There is lineage from them to the Kardashianisation not only of the music industry, but the wider culture."[169] The Irish Independent's Tanya Sweeney agreed that "[t]he vapidity of paparazzi culture could probably be traced back to the Spice Girls' naked ambitions",[172] while Mckie predicted that, "[f]or all that modern stars from Katy Perry to Lionel Messi exploit brand endorsements and attract tabloid coverage, the scale of the Spice Girls' breakthrough in 1996 is unlikely to be repeated—at least not by a music act."[169]

1990s icons

The Spice Girls have been labelled the biggest pop phenomenon of the 1990s[2][15] due to their international record sales, iconic symbolism and "omnipresence" in the late 1990s.[187][215][223] The group appeared on the cover of the July 1997 edition of Rolling Stone accompanied with the headline, "Spice Girls Conquer the World".[224] At the 2000 Brit Awards, the group received the Outstanding Contribution to Music Award to mark their success in the global music scene in the 1990s.[225] The iconic symbolism of the Spice Girls in the 1990s is partly attributed to their era-defining outfits,[187] the most notable being the Union Jack dress that Geri Halliwell wore at the 1997 Brit Awards. The dress has achieved iconic status, becoming one of the most prominent symbols of 1990s pop culture.[226] The status of the Spice Girls as 1990s pop icons is also attributed to their vast merchandising and willingness to be a part of a media-driven world.[169] Their unprecedented appearances in adverts and the media solidified the group as a phenomenon—an icon of the decade and for British music.[1][141]

Some sources, especially those in the United Kingdom, regard the Spice Girls as gay icons.[227][228] In a UK survey of more than 5,000 gay men and women, Victoria Beckham placed 12th and Halliwell placed 43rd in a ranking of the Top 50 gay icons of all time.[229] Halliwell was also the recipient of the Honorary Gay Award at the 2016 Attitude Awards.[230] In a 2005 interview, Emma Bunton attributed their large gay fan base to the group's fun-loving nature, open-mindedness and their love of fashion and dressing up, concluding that: "I'm so flattered that we've got such a huge gay following, it's amazing."[231]

In 1999, a study conducted by the British Council found that the Spice Girls were the second-best-known Britons internationally—only behind then-Prime Minister Tony Blair—and the best-known Britons in Asia.[232][233] In 2004, they featured in the VH1 series I Love the '90s for the year 1997, which was broadcast in the United States.[234] In 2005, Emma Bunton was a presenter on the VH1 sequel, I Love the '90s: Part Deux, with 1998 covering Geri Halliwell's exit from the group.[235] In 2006, ten years after the release of their debut single, the Spice Girls were voted the biggest cultural icons of the 1990s with 80 per cent of the votes in a UK poll of 1,000 people carried out for the board game Trivial Pursuit, stating that "Girl Power" defined the decade.[223][236] The Spice Girls also ranked number ten in the E! TV special, The 101 Reasons the '90s Ruled.[237]

Portrayal in the media

The Spice Girls became media icons in Great Britain and a regular feature of the British press.[218][238] During the peak of their worldwide fame in 1997, the paparazzi were constantly seen following them everywhere[222] to obtain stories and gossip about the group, as a supposed affair between Emma Bunton and manager Simon Fuller, or constant split rumours which became fodder for numerous tabloids.[238][239][240][241] Rumours of in-fighting and conflicts within the group also made headlines, with the rumours suggesting that Geri Halliwell and Melanie Brown in particular were fighting to be the leader of the group.[9] Brown, who later admitted that she used to be a "bitch" to Halliwell, said the problems had stayed in the past.[242] The rumours reached their height when the Spice Girls dismissed their manager Simon Fuller during the power struggles, with Fuller reportedly receiving a £10 million severance cheque to keep quiet about the details of his sacking.[9][240][241] Months later, in May 1998, Halliwell would leave the band amid rumours of a falling out with Brown; the news of Halliwell's departure was covered as a major news story by media around the world,[243] and became one of the biggest entertainment news stories of the decade.[244]

In February 1997 at the Brit Awards, Halliwell's Union Jack dress from the Spice Girls' live performance made all the front pages the next day. During the ceremony, Halliwell's breasts were exposed twice, causing controversy.[16] In the same year, nude glamour shots of Halliwell taken earlier in her career were released,[238] causing some scandal.[218] According to the group's official documentary Giving You Everything, the rest of the group had been fully aware of Halliwell's glamour modelling past, but the photos still created friction inside the group when they were published.

The stories of their encounters with other celebrities also became fodder for the press;[238][245] for example, in May 1997, at The Prince's Trust 21st-anniversary concert, Mel B and Geri Halliwell breached royal protocol when they planted kisses on Prince Charles's cheeks, leaving it covered with lipstick, and later, Halliwell told him "you're very sexy" and also pinched his bottom.[246] In November, the British royal family were considered fans of the Spice Girls, including The Prince of Wales and his sons Prince William and Prince Harry.[247][248][249] That month, South African President Nelson Mandela said: "These are my heroes. This is one of the greatest moments in my life"[250] in an encounter organised by Prince Charles, who said, "It is the second greatest moment in my life, the first time I met them was the greatest".[250] Prince Charles would later send Halliwell a personal letter "with lots of love" when he heard that she had quit the Spice Girls.[246] In 1998 the video game magazine Nintendo Power created The More Annoying Than the Spice Girls Award, adding: "What could possibly have been more annoying in 1997 than the Spice Girls, you ask?".[251]

Victoria Adams started dating football player David Beckham in late 1997 after they had met at a charity football match.[252] The couple announced their engagement in 1998[253] and were dubbed "Posh and Becks" by the media, becoming a cultural phenomenon in their own right.[254]

Other brand ventures

Film

In June 1997, the group began filming their movie debut with director Bob Spiers. Meant to accompany the album, the comical style and content of the movie was in the same vein as the Beatles' films in the 1960s such as A Hard Day's Night. The light-hearted comedy, intended to capture the spirit of the Spice Girls, featured a plethora of stars including Roger Moore, Hugh Laurie, Stephen Fry, Elton John, Richard O'Brien, Bob Hoskins, Jennifer Saunders, Richard E. Grant, Elvis Costello and Meat Loaf.[255]

Released in December 1997, Spiceworld: The Movie proved to be a hit at the box office, breaking the record for the highest-ever weekend debut for Super Bowl Weekend (25 January 1998) in the US, with box office sales of $10,527,222. The movie took in a total of $151 million at the box office worldwide.[9] Despite being a commercial success, the film was widely panned by critics; the movie was nominated for seven awards at the 1999 Golden Raspberry Awards where the Spice Girls collectively won the award for "Worst Actress". Since 18 July 2014, the Spice Bus, which was driven by Meat Loaf in the film, is now on permanent display at the Island Harbour Marina on the Isle of Wight, England.[256]

Considered a cult film, many publications described it as a brilliant film of the parody genre, that mocks both the star system and clichés of the cinema, while giving many winks to popular culture of the time.[257][258][259][260][261]

Television

The Spice Girls have starred in several television specials, documentaries and commercials since their debut in 1996. They have hosted various television specials. In November 1997, the Spice Girls became the first pop group to host ITV's An Audience with...;[66] their show featured an all-female audience and was watched by 11.8 million viewers in the UK, one fifth of the country's total population.[67] They have also hosted Christmas Eve and Christmas Day Top of the Pops television specials on BBC One.[262][263] Concert specials of their 1997 Girl Power! Live in Istanbul,[264] 1998 Spiceworld Tour[265] and 1999 Christmas in Spiceworld tours were also broadcast in various countries.

The Spice Girls have released at least seven official behind-the-scenes television documentaries, including two tour documentaries and two making-of documentaries for their film Spice World. They have also been the subject of a number of unofficial documentaries, commissioned and produced by individuals independent of the group. These documentaries usually focus on the group's career and their cultural impact. The Spice Girls have had episodes dedicated to them in several music biography series, including VH1's Behind the Music, E! True Hollywood Story and MTV's BioRhythm. The Spice Girls have appeared and performed in numerous television shows and events. Notable appearances include Saturday Night Live (SNL), The Oprah Winfrey Show, two Royal Variety Performances and the 2012 Summer Olympics closing ceremony. The group has also starred in television commercials for brands including Pepsi (where they sang "Move Over", given the additional subtitle "Generationext" which is a prominent lyric in the song), Polaroid, Walkers Crisps, Impulse and Tesco.[266]

Viva Forever!

A jukebox musical written by Jennifer Saunders, produced by Judy Craymer and directed by Paul Garrington. Based on the songs of the Spice Girls, the show began previews at the Piccadilly Theatre in the West End on 27 November 2012 and had its Press Night on 11 December 2012 and features some of the group's biggest hit songs including "Wannabe", "Spice Up Your Life" and the eponymous "Viva Forever".[267]

Merchandise and sponsorship deals

In 1997, the Spice Girls were involved in a prolific merchandising phenomenon, becoming the most merchandised group in music history[217] with estimated earnings of over £300 million from their merchandising and endorsement deals that year alone.[268] They negotiated lucrative deals with many brands, including Pepsi, Asda, Cadbury and Target, which led to accusations of "selling out" and overexposure.[62] The group responded to the press' criticisms by launching the music video for "Spice Up Your Life" in which they parody the number of sponsorships they had. In their 2019 reunion, they teamed up with the children's book franchise Mr. Men, creating many derivative products such as books, cups, bags and coasters.[269][270][271]

In conjunction with the beginning of the Spice World – 2019 Tour, the Spice Girls launched an advertising campaign with Walkers potato crisps who they had previously worked with in the 1990s.[272] The campaign was to find their "best-ever fan" and included Spice Girls branded products in supermarkets to promote their "best-ever" Cheese & Onion flavouring and a television advertisement which was premiered during a commercial break for 2019's Britain's Got Talent semi-finals.[273] The "best-ever fan" would receive the chance to meet the Spice Girls on a date of their tour.[274]

Career records and achievements

As a group, the Spice Girls have received a number of notable awards including five Brit Awards, three American Music Awards, four Billboard Music Awards, three MTV Europe Music Awards, one MTV Video Music Award and three World Music Awards. In 2000, they received the Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to the British Music Industry, previous winners include Elton John, the Beatles and Queen. They have sold 85 million records worldwide,[275][276] achieving certified sales of 13 million albums in Europe,[40] 14 million records in the US[42] and 2.4 million in Canada.[60] The group achieved the highest-charting debut for a UK group on the Billboard Hot 100 at number five with "Say You'll Be There". They are also the first British band since the Rolling Stones in 1975 to have two top-ten albums in the US Billboard 200 albums chart at the same time (Spice and Spiceworld).[61] In addition to this, the Spice Girls also achieved the highest-ever annual earnings by an all-female group in 1998 with an income of £29.6 million (approximately US$49 million).[277] In 1999, they were ranked sixth in Forbes' inaugural Celebrity 100 Power Ranking.[278]

They produced a total of nine number one singles in the UK—tied with ABBA behind Take That (eleven), The Shadows (twelve), Madonna (thirteen), Westlife (fourteen), Cliff Richard (fourteen), the Beatles (seventeen) and Elvis Presley (twenty-one). The group had three consecutive Christmas number-one singles in the UK ("2 Become 1", 1996; "Too Much", 1997; "Goodbye", 1998); they only share this record with the Beatles.[279] Their first single, "Wannabe", is the most successful song released by an all-female group.[25][194] Debuting on the US Billboard Hot 100 chart at number eleven, it is also the highest-ever-charting debut by a British band in the US, beating the previous record held by the Beatles for "I Want to Hold Your Hand" and the joint highest entry for a debut act, tying with Alanis Morissette.[16]

Spice is the 18th-biggest-selling album of all time in the UK with over 3 million copies sold, and topped the charts for 15 non-consecutive weeks, the most by a female group in the UK.[38] It is also the biggest-selling album of all time by a girl group, with sales of over 23 million copies worldwide.[7] Spiceworld shipped 7 million copies in just two weeks, including 1.4 million in Britain alone—the largest-ever shipment of an album over 14 days.[280] They are also the first act (and so far only female act) to have their first six singles ("Wannabe", "Say You'll Be There", "2 Become 1", "Mama"/"Who Do You Think You Are", "Spice Up Your Life" and "Too Much") make number one on the UK charts. (Their run was broken by "Stop", which peaked at number two in March 1998.)

Spiceworld: The Movie broke the record for the highest-ever weekend debut a film on Super Bowl weekend (25 January 1998) in the US, with box office sales of $10,527,222. Spiceworld: The Movie topped the UK video charts on its first week of release, selling over 55,000 copies on its first day in stores and 270,000 copies in the first week.[281][282] The Return of the Spice Girls Tour was announced as the highest-grossing concert act of 2008, measured as the twelve months ended April 2008.[99] The 17-night sellout stand at the O2 Arena in London was the highest-grossing engagement of the year, netting £16.5 million (US$33 million) for the group and drawing an audience of 256,647, winning the 2008 Billboard Touring Award for Top Boxscore.[283][284] In total, the 47-date tour took in more than $70 million[285] and produced $107.2 million in ticket sales and merchandising.[105] The 3-night sellout stand at Wembley Stadium for the Spice World – 2019 Tour was the highest-grossing engagement of the year drawing an audience of 221,971, winning the 2019 Billboard Live Music Award for Top Boxscore.[286]

In popular culture

In February 1997, the "Sugar Lumps", a satirical version of the Spice Girls played by Kathy Burke, Dawn French, Llewella Gideon, Lulu and Jennifer Saunders, filmed a video for British charity Comic Relief. The video starts with the Sugar Lumps as schoolgirls who really want to become pop stars like the Spice Girls, and ends with them joining the group on stage, while dancing and lip-syncing the song "Who Do You Think You Are".[287] The Sugar Lumps later joined the Spice Girls during their live performance of the song on Comic Relief's telethon Red Nose Day event in March 1997.[288] In January 1998, a fight between animated versions of the Spice Girls and pop band Hanson was the headlining matchup in MTV's claymation parody Celebrity Deathmatch Deathbowl '98 special that aired during the Super Bowl XXXII halftime.[289][290] The episode became the highest-rated special in the network's history and MTV turned the concept into a full-fledged television series soon after.[291]

In March 2013, the Glee characters Brittany (Heather Morris), Tina (Jenna Ushkowitz), Marley (Melissa Benoist), Kitty (Becca Tobin) and Unique (Alex Newell) dressed up as the Spice Girls and performed the song "Wannabe" on the 17th episode of the fourth season of the show.[292] In April 2016, the Italian variety show Laura & Paola on Rai 1 featured the hosts, Grammy Award-winning singer Laura Pausini and actress Paola Cortellesi, and their guests, Francesca Michielin, Margherita Buy and Claudia Gerini, dressed up as the Spice Girls to perform a medley of Spice Girls songs as part of a 20th-anniversary tribute to the band.[293][294] In December 2016, the episode "Who Needs Josh When You Have a Girl Group?" of the musical comedy-drama series Crazy Ex-Girlfriend featured cast members Rachel Bloom, Gabrielle Ruiz and Vella Lovell performing an original song titled "Friendtopia", a parody of the Spice Girls' songs and "girl power" philosophy.[295][296] Rapper Aminé's 2017 single "Spice Girl" is a reference to the group, and the song's music video includes an appearance by Mel B.[297]

In the late 1990s, Spice Girls parodies appeared in various American sketch comedy shows including Saturday Night Live (SNL), Mad TV[298] and All That. A January 1998 episode of SNL featured cast members, including guest host Sarah Michelle Gellar, impersonating the Spice Girls for two "An Important Message About ..." sketches.[299] In September 1998, the show once again featured cast members, including guest host Cameron Diaz, impersonating the Spice Girls for a sketch titled "A Message from the Spice Girls".[300][301] Nickelodeon's All That had recurring sketches with the fictional boy band "The Spice Boys", featuring cast members Nick Cannon as "Sweaty Spice", Kenan Thompson as "Spice Cube", Danny Tamberelli as "Hairy Spice", Josh Server as "Mumbly Spice", and a skeleton prop as "Dead Spice".[302]

Parodies of the Spice Girls have also appeared in major advertising campaigns. In 1997, Jack in the Box, an American fast-food chain restaurant, sought to capitalise on "Spice mania" in America by launching a national television campaign using a fictional girl group called the Spicy Crispy Chicks (a take off of the Spice Girls) to promote the new Spicy Crispy Sandwich. The Spicy Crispy Chicks concept was used as a model for another successful advertising campaign called the 'Meaty Cheesy Boys'.[139][303] At the 1998 Association of Independent Commercial Producers (AICP) Show, one of the Spicy Crispy Chicks commercials won the top award for humour.[304] In 2001, prints adverts featuring a parody of the Spice Girls, along with other British music icons consisting of the Beatles, Elton John, Freddie Mercury and the Rolling Stones, were used in the Eurostar national advertising campaign in France. The campaign won the award for Best Outdoor Campaign at the French advertising CDA awards.[305][306] In September 2016, an Apple Music advert premiered during the 68th Primetime Emmy Awards that featured comedian James Corden dressed up as various music icons including all five of the Spice Girls.[307]

Other notable groups of people have been labelled as some variation of a play-on-words on the Spice Girls' name as an allusion to the band. In 1997, the term "Spice Boys" emerged in the British media as a term coined to characterise the "pop star" antics and lifestyles off the pitch of a group of Liverpool F.C. footballers that includes Jamie Redknapp, David James, Steve McManaman, Robbie Fowler and Jason McAteer.[308] The label has stuck with these footballers ever since, with John Scales, one of the so-called Spice Boys, admitting in 2015 that, "We're the Spice Boys and it's something we have to accept because it will never change."[309] In the Philippines, the "Spice Boys" tag was given to a group of young Congressmen of the House of Representatives who initiated the impeachment of President Joseph Estrada in 2001.[310][311] The Australian/British string quartet Bond were dubbed by the international press as the "Spice Girls of classical music" during their launch in 2000 due to their "sexy" image and classical crossover music that incorporated elements of pop and dance music. A spokeswoman for the quartet said in response to the comparisons, "In fact, they are much better looking than the Spice Girls. But we don't welcome comparisons. The Bond girls are proper musicians; they have paid their dues."[312][313] The Women's Tennis Association (WTA) doubles team of Martina Hingis and Anna Kournikova, two-time Grand Slam and two-time WTA Finals Doubles champions, dubbed themselves the "Spice Girls of tennis" in 1999.[314][315] Hingis and Kournikova, along with fellow WTA players Venus and Serena Williams, were also labelled the "Spice Girls of tennis", then later the "Spite Girls",[316][317] by the media in the late 1990s due to their youthfulness, popularity and brashness.[318]

Wax sculptures of the Spice Girls are currently on display at the famed Madame Tussaud’s New York wax museum.[319][320] The sculptures of the Spice Girls (sans Halliwell) were first unveiled in December 1999, making them the first pop band to be modelled as a group since the Beatles in 1964 at the time.[321] A sculpture of Halliwell was later made in 2002,[322] and was eventually displayed with the other Spice Girls' sculptures after Halliwell reunited with the band in 2007. Since 2008, "Spiceworld: The Exhibition", a collection of over 5,000 Spice Girls memorabilia and merchandise, has been showcased in museums across the UK, including the Leeds City Museum in 2011,[323] Northampton Museum and Art Gallery in 2012,[324] Tower Museum in 2012,[325] Ripley's Believe It or Not! London and Blackpool museums in 2015[326] and 2016,[327] and the Watford Colosseum in 2016.[190][328] The collection is owned by Liz West, the Guinness World Record holder for the largest collection of Spice Girls memorabilia.[329][330] The Spice Girls themselves have contributed items to the exhibition.[331] "The Spice Girls Exhibition", a collection of over 1,000 Spice Girls items owned by Alan Smith-Allison, was held at the Trakasol Cultural Centre in Limassol Marina, Cyprus in the summer of 2016.[332] "Wannabe 1996-2016: A Spice Girls Art Exhibition", an exhibition of Spice Girls-inspired art, was held at The Ballery in Berlin in 2016 to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the group's debut single, "Wannabe".[333][334]

Discography

- Spice (1996)

- Spiceworld (1997)

- Forever (2000)

Concerts

- Girl Power! Live in Istanbul (1997)

- Spiceworld Tour (1998)

- Christmas in Spiceworld Tour (1999)

- The Return of the Spice Girls Tour (2007–08)

- Spice World – 2019 Tour (2019)

Members

- Geri Halliwell – vocal (1994–1998, 2007-2008, 2012, 2016, 2018-present)

- Melanie Chisholm – vocal (1994–2001, 2007-2008, 2012, 2018-present)

- Victoria Beckham – vocal (1994–2001, 2007-2008, 2012)

- Melanie Brown – vocal (1994–2001, 2007-2008, 2012, 2016, 2018-present)

- Emma Bunton – vocal (1994–2001, 2007-2008, 2012, 2016, 2018-present)

Publications

- Girl Power: The Official Book by the Spice Girls, Andre Deutsch Ltd (27 March 1997) ISBN 9780233991658

- Real Life : Real Spice: The Official Story by the Spice Girls, Andre Deutsch Ltd (23 October 1997) ISBN 9780233992990

- Geri "Ginger Nutter": Official Spice Girls Pocket Books, Andre Deutsch Ltd (23 October 1997) ISBN 9780233993218

- Emma "Baby Talking": Official Spice Girls Pocket Books, Andre Deutsch Ltd (23 October 1997) ISBN 9780233993225

- Mel C "Tuff Enuff": Official Spice Girls Pocket Books, Andre Deutsch Ltd (23 October 1997) ISBN 9780233993249

- Victoria "The High Life": Official Spice Girls Pocket Books, Andre Deutsch Ltd (23 October 1997) ISBN 9780233993256

- Mel B "Don't Be Scared": Official Spice Girls Pocket Books, Andre Deutsch Ltd (23 October 1997) ISBN 9780233993232

- Spice World The Movie: The Official Book of the Film, Ebury Press (26 November 1997) ISBN 9780091864200

- Forever Spice, Little, Brown & Company (4 November 1999) ISBN 9780316853613

See also

- List of best-selling girl groups

- List of best-selling music artists

- List of awards received by the Spice Girls

References

Citations

- Inness, Sherrie A. (1998). Millennium Girls: Today's Girls Around the World. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 115. ISBN 978-0847691371.

- "Spice Girls Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- Waxman, Olivia B. (8 July 2016). "An Important Lesson in British History From the Spice Girls". TIME. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- Wong, Sterling (13 April 2011). "Are Adele, Mumford And Sons Sign of a New British Invasion? – Music, Celebrity, Artist News". MTV News. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- "Simon Fuller: Guiding pop culture". BBC News. 18 June 2003. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- Jeffrey, Don (8 February 1997). "Girl Power! Spice Girls". Billboard. 109 (6): 5. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Caulfield, Keith (24 May 2017). "Rewinding the Charts: In 1997, Spice Girls Powered to No. 1". Billboard. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- "The Spice Girls Re-Release 'The Greatest Hits' And 'Spiceworld' On Vinyl". Yahoo Sports. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Svetkey, Benjamin (17 July 1998). "Spice Girl's Tour Divorce". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Heidi Sherman (2 June 1998). "Ginger Spice's Departure Marks "End of the Beginning"" (DOC). Rolling Stone. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- "New Spice Girls documentary on BBC One". BBC. 19 October 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- "1998: Ginger leaves the Spice Girls". BBC. 31 May 1998. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- Dawson, Ryan. "Beatlemania and Girl Power: An Anatomy of Fame". Bigger Than Jesus: Essays On Popular Music. University of Cambridge. Archived from original on 28 April 2005. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- Sinclair (2004), p. IX

- Spice Girls form The Guardian. Retrieved 18 September 2011

- Spice Girls Official. "Timeline Archived 24 September 2012 at WebCite". Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- Rob, McGibbon (1997). Spice Power: The Inside Story. p. 52.

- Sinclair (2004), p. 29

- Sinclair (2004). According to Bob Herbert, she was fired because "she just wasn't fitting in... she would never have gelled with it and I had to tell her to go". (Sinclair, p. 30). Stephenson later challenged Herbert's claim, stating that it was her decision to leave due to her mother being diagnosed with breast cancer. Adams later dismissed this claim, saying she "just couldn't be arsed" to put in the work the rest of the group was doing. (Sinclair, p. 31)

- Sinclair (2004), p. 33

- Sinclair (2004)

- "How the Spice Girls Ripped 'Girl Power' from Its Radical Roots". Vice. 5 November 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- Sinclair, David (2004). Wannabe: How the Spice Girls Reinvented Pop Fame. Omnibus Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-7119-8643-6.

- Gorman, Paul. "Taking On The Britboys: Spice Girls". Music Week. April 1996. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- MTV News staff (1 October 1997). "Spice Girls, PMS on the Money". MTV News. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- McGibbon, Rob (1997). Spice Power: The Inside Story. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 124, 125. ISBN 0752211420.

- Myers, Justin (1 December 2016). "Classic Christmas Number 1s: Spice Girls' 2 Become 1". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- Myers, Justin (20 October 2016). "Flashback to 1996: Spice Girls hit Number 1 with Say You'll Be There". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "The Sun's 1997 "Spice Mania" cover". 9 July 1997. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "20 Alternative Rock Hits Turning 20 in 2017". Billboard. 12 January 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- Epstein, Leonora (8 January 2016). "The power of growing up with the Spice Girls". HelloGiggles. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "Spice mania returns for reunion". BBC News. 3 December 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "Ginger snaps". BBC News. 31 May 1998. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- "The Fab Five Make Way For The Spice Girls!". New York Daily News. 9 November 1997. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- "Spice Girls fan, 29, spends £10k on shrine to the Fab Five in his bedroom". Metro. 10 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "Spice Girls get dolled up". CNN. 16 October 1997. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- UK Sales certificates database. British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- Every Hit. Best-Selling Albums of All Time. UK Database, Spice sold 2.9 million.

- "Little Mix's Glory Days is the longest-reigning girl group Number 1 since Spice Girls' debut 20 years ago" UK Official Charts. Retrieved 13 February 2017

- "European sales certificate for Spice". IFPI. Archived from the original on 6 March 2006. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- "Spice Girls Wannabe". lyriczz.com. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- USA sales certificates database. RIAA. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- Ask Billboard July 2007. US Spice Girls album sales. Retrieved 13 February 2017. Archived 17 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Gold and Platinum: Top 100 Albums Archived 25 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- "It has been 20 years since Geri Halliwell wore the Union Jack dress". Harper’s Bazaar. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Spice Girls Win two Brits Pag.3 BBC News, 28 June 2007.

- Alexander, Hilary (19 May 2010). "Online poll announces the top ten most iconic dresses of the past fifty years – Telegraph". fashion.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- The Spice Girls; Cripps, Rebecca; & Peachey, Mal (1997). Real Life: Real Spice The Official Story. London: Zone Publishers. ISBN 0-233-99299-5

- Solomons, Mark (20 September 1997). "Newsline: Music Video Shipments". Billboard. 109 (38): 45. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Sinclair (2004), pp. 102–103

- “1997 MTV Video Music Awards”. MTV. Retrieved 20 September 2011

- "Princess's Death Overshadows Music Awards". BBC. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "8th Annual Billboard Music Awards Draws A Record Crowd". Billboard. 109 (52): 50. 27 December 1997. ISSN 0006-2510.

- "Spice Girls". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "'Tens of thousands of tots empty their lungs': relive the Spice Girls' first tour". The Guardian. 24 May 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Spice Girls launch poppy appeal". BBC News. 29 October 1997. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Now Mandela swaps political power for girl power". BBC News. 1 November 1997. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Wild, David (11 December 1997). "Spice World". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards". International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on 6 March 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Gold/Platinum". Music Canada. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Bronson, Fred (14 February 1998). "Usher Seesaws In The U.S., U.K." Billboard. 110 (7): 116. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- "The Spice Girls". Lifetime UK. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Spice Girls scoop MTV Europe best group award". BBC News. 7 September 1997. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Halliwell 1999, p. 374

- "The man with stars in his eyes". The Guardian. 14 January 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "30 Years of An Audience With, Episode 1". ITV. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 18 July 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- Sinclair 2004, p. 148

- 'Spiceworld' Album Sales Jump, as Spice Girls' New Pop Vehicle Steadily Gains Velocity Archived 18 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. PR Newswire. 20 November 1997. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- 25th American Music Awards Rock on the Net. Retrieved 27 February 2012

- Stark, David (7 February 1998). "Brits Around the World '98: Brit Publishers are Scoring all over the World". Billboard. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- BRIT Awards 1998. Best-selling British Album Act: Spice Girls Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- Girl Power coming to Wembley. BBC News. 18 September 1998.

- "Ginger snaps". BBC News. 31 May 1998. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- Millard, Rosie (31 May 1998). "Yes, Geri - it's hard to break out when you're cast in plastic". The Independent. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Spice Girls Break-Up Shook Up 1998". Billboard. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Spice Girls Ltd v Aprilia World Service BV [2002] EWCA Civ 15; [2002] EMLR 27 CA.

- McKendrick, Ewan (2010). Contract Law – Text, Cases, Materials, 4th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 588–592. ISBN 978-0-19-957979-2.

- Myers, Justin (20 December 2013). "Official Charts Flashback 1998: Spice Girls – Goodbye". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- BBC News. Entertainment: Spice Girls take MTV crown. Chisholm shouted:"We've done it again".

- Dougherty, Steve (27 November 2000). "Bitter Season". People. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "David and Victoria tie the knot". BBC News. 5 July 1999. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- Beech, Richard (13 February 2015). "Spice Girls producer was duped into leaking songs by fraudster now selling them for £10,000 EACH". Mirror. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "In brief | UK news | The Guardian". theguardian.com. December 1999.

- Kennedy, Maev (3 March 2000). "Spice Girls win lifetime achievement award". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Hunter, James. "Forever – Review". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 11 March 2006. Archived 7 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Westlife triumph in album battle". BBC News. 13 November 2000. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- "Spice Girls make pop history". BBC News. 29 October 2000. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "2014 MTV EMA nominations: Top 10 most memorable EMA moments". Nottingham Post. 18 September 2014. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015.

- Griffe David and Victoria Beckham: Carreira com as Spice Girls (Portuguese). Perfumes – A Moda Invisível. ISBN 9788563229083. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- “Spice Girls Go On Forever”. Dotmusic. Retrieved 27 October 2019

- "Spice Girls dismiss comeback plan". BBC. Retrieved 18 September 2011

- Spice Girls announce reunion tour BBC News. 28 June 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Finn, Natalie. "'A Well Seasoned Rumour". E! Online. 8 June 2007.

- ""Spice Girls" home page (including announcement)". TheSpiceGirls.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- DailyTelegraph (14 December 2007). "Spice impersonators hit OZ". Herald Sun. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- New Spice Girls documentary on BBC One on 31 December. BBC Press Office. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- BBC News. Fans snap up Spice Girls tickets. BBC. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- Spice Girls add more dates to tour. The Press Association. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- Randall, David K. (11 August 2008). "Spice Girls, Prince Rake in Concert Cash". ABC News. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- BBC News. Spice Girls add new London dates. BBC. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- "Spice Girls wow Canada in first of reunion concerts". The Times. 3 December 2007. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2007.