Sydenham's chorea

Sydenham's chorea, also known as chorea minor and historically and occasionally referred to as St Vitus' dance, is a disorder characterized by rapid, uncoordinated jerking movements primarily affecting the face, hands and feet.[1] Sydenham's chorea results from childhood infection with Group A beta-haemolytic Streptococcus[2] and is reported to occur in 20–30% of people with acute rheumatic fever. The disease is usually latent, occurring up to 6 months after the acute infection, but may occasionally be the presenting symptom of rheumatic fever. Sydenham's chorea is more common in females than males and most below 16 years of age. Adult onset of Sydenham's chorea is comparatively rare, and the majority of the adult cases are associated with exacerbation of chorea following childhood Sydenham's chorea.

| Sydenham's chorea | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Chorea minor, St Vitus' dance |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Signs and symptoms

Sydenham's chorea is characterized by the abrupt onset (sometimes within a few hours) of neurologic symptoms, classically chorea, usually affecting all four limbs. Other neurologic symptoms include behavior change, dysarthria, gait disturbance, loss of fine and gross motor control with resultant deterioration of handwriting, headache, slowed cognition, facial grimacing, fidgetiness and hypotonia.[3][4] Also, there may be tongue fasciculations ("bag of worms") and a "milk sign", which is a relapsing grip demonstrated by alternate increases and decreases in tension, as if hand milking.[5]

Non-neurologic manifestations of acute rheumatic fever are carditis, arthritis, erythema marginatum, and subcutaneous nodules.[3]

The PANDAS (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections) syndrome is similar, but is not characterized by Sydenham's motor dysfunction. PANDAS presents with tics and/or a psychological component (e.g., OCD) and occurs much earlier, days to weeks after GABHS infection rather than 6–9 months later.[6] It may be confused with other conditions such as lupus and Tourette syndrome.

Movements cease during sleep, and the disease usually resolves after several months. Unlike in Huntington's disease, which is generally of adult onset and associated with an unremitting autosomal dominant movement disorder and dementia, neuroimaging in Sydenham's chorea is normal and other family members are unaffected. Other disorders that may be accompanied by chorea include abetalipoproteinemia, ataxia–telangiectasia, biotin-thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease, Fahr disease, familial dyskinesia–facial myokymia (Bird–Raskind syndrome) due to an ADCY5 gene mutation, glutaric aciduria, Lesch–Nyhan syndrome, mitochondrial disorders, Wilson disease, hyperthyroidism, lupus erythematosus, pregnancy (chorea gravidarum), and side effects of certain anticonvulsants or psychotropic agents.

Causes

A major manifestation of acute rheumatic fever, Sydenham's chorea is a result of an autoimmune response that occurs following infection by group A β-hemolytic streptococci[7] that destroys cells in the corpus striatum of the basal ganglia.[4][7][8] Molecular mimicry to streptococcal antigens leading to an autoantibody production against the basal ganglia has long been thought to be the main mechanism by which chorea occurs in this condition. In 2012, antibodies in serum to the cell surface antigen; dopamine 2 receptor were shown in up to a third of patients in a cohort of Sydenham's chorea. [9] Dopamine receptor autoantibodies correlate with clinical symptoms.[10] Whether these antibodies represent an epi-phenomenon or are pathogenic, remains to be proven.

There are many causes of childhood chorea, including cerebrovascular accidents, collagen vascular diseases, drug intoxication, hyperthyroidism, Wilson's disease, Huntington's disease, abetalipoproteinemia, Fahr disease, biotin-thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease due to mutations in the SLC19A3 gene, Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, and infectious agents.[3]

Diagnosis

The health care provider will perform a physical exam. Detailed questions will be asked about the symptoms.

If a streptococcus infection is suspected, tests will be done to confirm the infection. These include:

- Throat swab

- Anti-DNAse B blood test

- Antistreptolysin O blood test

Further testing may include:

- Blood tests such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, complete blood count

- Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scan of the brain[11]

Treatment

Treatment of Sydenham's chorea is based on the following principles:{[cn}}

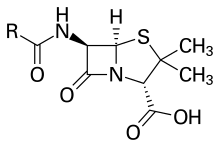

- The first tenet of treatment is to eliminate the streptococcus at a primary, secondary and tertiary level. Strategies involve the adequate treatment of throat and skin infections, with a course of penicillin when Sydenham's chorea is newly diagnosed, followed by long-term penicillin prophylaxis. Behavioural and emotional changes may precede the movement disorders in a previously well child.

- Treatment of movement disorders. Therapeutic efforts are limited to palliation of the movement disorders. Haloperidol is frequently used because of its anti-dopaminergic effect. It has serious potential side-effects, e.g., tardive dyskinesia. In a study conducted at the RFC, 25 out of 39 patients on haloperidol reported side-effects severe enough to cause the physician or parent to discontinue treatment or reduce the dose. Other medications which have been used to control the movements include pimozide, clonidine, valproic acid, carbamazepine and phenobarbitone.

- Immunomodulatory interventions include steroids, intravenous immunoglobulins, and plasma exchange. Patients may benefit from treatment with steroids; controlled clinical trials are indicated to explore this further.

- There are several historical case series reporting successful treatment of Sydenham's chorea by inducing fever.[12][13]

Prognosis

Fifty percent of patients with acute Sydenham's chorea spontaneously recover after two to six months whilst mild or moderate chorea or other motor symptoms can persist for up to and over two years in some cases. Sydenham's is also associated with psychiatric symptoms with obsessive–compulsive disorder being the most frequent manifestation.

History

Sydenham's chorea became a well-defined disease entity only during the second half of the nineteenth century. Such progress was promoted by the availability of large series of clinical data provided by newly-founded paediatric hospitals. A 2005 study examined the demographic and clinical features of patients with chorea admitted to the first British paediatric hospital (the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London) between 1852 and 1936. The seasonal and demographic characteristics of Sydenham's chorea during this time appear strikingly similar to those observed today, Great Ormond Street hospital case notes provide detailed descriptions of the "typical cases" of Sydenham's chorea, and show that British physicians working in the early age of paediatric hospitals recognized the most distinctive clinical features of this condition.[14]

Throughout the nineteenth century the term "chorea" referred to an ill-defined spectrum of hyperkinesias, including those recognised today as chorea, tics, dystonia, or myoclonus. William Osler stated, "In the whole range of medical terminology there is no such olla podrida as Chorea, which for a century has served as a sort of nosological pot into which authors have cast indiscriminately affections characterised by irregular, purposeless movements."[14]

Sydenham's chorea, a frequent cause of paediatric acute chorea, is a major manifestation of rheumatic fever. The association of chorea with rheumatism was first reported in 1802, and confirmed in the following decades by several French and English authors.[14] The inclusion of chorea under the rheumatic umbrella helped discriminate Sydenham's chorea from other "choreic" syndromes. The incidence of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease is not declining. Recent figures quote the incidence of Acute Rheumatic Fever as 0.6–0.7/1,000 population in the United States and Japan compared with 15–21/1,000 population in Asia and Africa.[15] The prevalence of Acute Rheumatic Fever and Sydenham's Chorea has declined progressively in developed countries over the last decades.[16][17] Physicians working in early children's hospitals recognised new clinical syndromes through the definition of "typical clinical cases". Complex multi-systemic diseases, such as rheumatic fever, were categorised only after the observation of large, hospital based series. Therefore, paediatric hospitals gradually became an important setting for the application of a modern "statistical averaging" technique to paediatric syndromes. Historical authorities in paediatrics, such as Walter Butler Cheadle and Octavius Sturges, worked at London's Hospital for Sick Children, and their clinical notes help elucidate how the typical case of Sydenham's chorea was defined.[14]

Between 1860 and 1900 the proportion of choreic patients ranged between 5% and 7% of the total number of patients admitted (mean per year, 1003), whereas from 1900 to 1936 it was constantly below 4% (mean per year). Chorea was the fourth most frequent cause of admission between 1860 and 1900, and in the 1880s temporarily became the second most frequent diagnosis among inpatients. Contemporary articles report a homogeneous distribution of paediatric chorea all over England However, since many choreic children were "cured" at home, the hospital based rates probably underestimate the incidence of chorea in the general paediatric population.[14]

A higher number of cases were admitted during the colder months, consistent with the reference epidemiological report on chorea at the end of the century. In the 1950s and 1960s the highest frequency of chorea was recorded during the winter months in several Northern and Central European countries. The incidence of rheumatism among Great Ormond Street Hospital inpatients peaked in October, preceding chorea by approximately two months. This is consistent with the current knowledge that most of the rheumatic fever symptoms appear about 10 days after the streptococcal infection, whereas Sydenham's chorea occurs typically 2–3 months after infection.

More than 80% of choreic patients were aged between 7 and 11 years (mean 9.2). Due to a referral bias, this age may be falsely low. Indeed, the British Medical Association (1887) reported the peak age between 11 and 15 years. In the present series, the female:male ratio was 2.7, in accordance with the general choreic population of Britain towards the end of the 1800s. In children below age 7, the female preponderance is less manifest. This was observed also by Charles West (founder physician of Great Ormond Street Hospital), and subsequently by Osler, who stated that "the second hemi-decade contains the greatest number of cases in males, and the third the greatest number in females". In the majority of the 20th century studies, female preponderance is evident only in children over 10 years of age. These observations suggest a role for oestrogen in Sydenham's chorea expression. Supporting this view, oral contraceptives and pregnancy can cause relapses of disease.[14]

Ten percent of the 1,548 patients whose records were researched for the British study were subsequently admitted with a relapse of chorea. Given that relapse admissions had a negative impact on the hospital cure rate, this rate might underestimate the actual relapse incidence in the general population of patients.[14]

Etymology

It is named after British physician Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689).[15][18] The alternate eponym, "Saint Vitus Dance", is in reference to Saint Vitus, a Christian saint who was persecuted by Roman emperors and died as a martyr in AD 303. Saint Vitus is considered to be the patron saint of dancers, with the eponym given as homage to the manic dancing that historically took place in front of his statue during the feast of Saint Vitus in Germanic and Latvian cultures.[19]

References

- "Sydenham Chorea Information Page" Archived 2010-07-22 at the Wayback Machine Saint Vitus Dance, Rheumatic Encephalitis from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Accessed April 26, 2008

- Sydenham's chorea Archived 2008-04-18 at the Wayback Machine Symptoms/Findings from WeMOVE.Org Accessed April 26, 2008

- Zomorrodi A, Wald ER (2006). "Sydenham's Chorea in Western Pennsylvania". Pediatrics. 117 (4): 675–679. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1573. PMID 16533893. S2CID 32478765.

- Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Shapiro MB (1993). "Sydenham's Chorea:Physical and Psychological Symptoms of St Vitus Dance". Pediatrics. 91 (4): 706–713. PMID 8464654.

- Medscape > Pediatric Rheumatic Heart Disease Clinical Presentation > Noncardiac manifestations. Author: Thomas K Chin, MD; Chief Editor: Stuart Berger, MD. Updated: August 4, 2010

- Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, et al. (February 1998). "Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical description of the first 50 cases". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 155 (2): 264–71. doi:10.1176/ajp.155.2.264 (inactive 2021-01-14). PMID 9464208.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Sydenham's Chorea Symptoms Archived 2008-04-18 at the Wayback Machine.Accessed September 24, 2009.

- Faustino PC, Terreri MT, Rocha AJ, et al. (2003). "Clinical, laboratory, psychiatric and magnetic resonance findings in patients with sydenham chorea". Neuroradiology. 45 (7): 456–462. doi:10.1007/s00234-003-0999-8. PMID 12811441. S2CID 23605799.

- Dale RC, Merheb V, Pillai S, et al. (2012). "Antibodies to surface dopamine-2 receptor in autoimmune movement and psychiatric disorders". Brain. 135 (11): 3453–3468. doi:10.1093/brain/aws256. PMID 23065479.

- Ben-Pazi H, Stoner JA, Cunningham MW (2013). "Dopamine receptor autoantibodies correlate with symptoms in Sydenham's chorea". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e73516. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...873516B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073516. PMC 3779221. PMID 24073196.

- "Sydenham chorea: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia".

- Sutton, LP; Dodge, KG (1933). "The treatment of chorea by induced fever". The Journal of Pediatrics. 3 (6): 813–26. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(33)80151-x.

- Sutton, LP; Dodge, KG (1936). "Fever therapy in chorea and in rheumatic carditis with and without chorea". The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 21 (6): 619–28.

- D Martino; A Tanner; G Defazio; A J Church; K P Bhatia; G Giovannoni; R C Dale (October 2004). "Tracing Sydenham's chorea: historical documents from a British paediatric hospital". Disease in Childhood. 90 (5): 507–511. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.057679. PMC 1720385. PMID 15851434.

- Walker K, Lawrenson J, Wilmshurst JM (2006). "Sydenham's Chorea-clinical and therapeutic update 320 years down the line". South African Medical Journal. 96 (9): 906–912.

- Nausieda PA, Grossman BJ, Koller WC, et al. (1980). "Sydenham's Chorea:An update". Neurology. 30 (3): 331–334. doi:10.1212/wnl.30.3.331. PMID 7189038. S2CID 21035716.

- Eshel E, Lahat E, Azizi E, et al. (1993). "Chorea as a manifestation of rheumatic fever-a 30-year survey". European Journal of Pediatrics. 152 (8): 645–646. doi:10.1007/bf01955239. PMID 8404967. S2CID 29611352.

- "Sydenham's chorea". Whonamedit. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- "St. Vitus Information Page - Star Quest Production Network". Saints.sqpn.com. 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

Further reading

- Martino D, Tanner A, Defazio G, et al. (May 2005). "Tracing Sydenham's chorea: historical documents from a British paediatric hospital". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 90 (5): 507–11. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.057679. PMC 1720385. PMID 15851434.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |