Taulantii

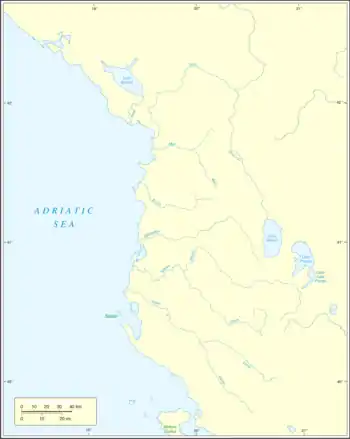

Taulantii or Taulantians[1] ("swallow-men"; Ancient Greek: Ταυλάντιοι, Taulantioi or Χελιδόνες, Khelidones; Latin: Taulantii) were an Illyrian people that lived on the Adriatic coast of southern Illyria (modern Albania). They dominated at various times much of the plain between the Drin and the Aous. The centre of Taulantian kingdom is likely to have been in the area of Tirana, in the hinterland of Dyrrah/Epidamnus.[2] The Taulantii are among the oldest attested Illyrian peoples, who established a powerful kingdom in southern Illyria.[3] They are among the peoples who most marked Illyrian history, and thus found their place in the numerous works of historians in classical antiquity.[4]

Etymology

An Illyrian people named Taulantii was firstly recorded by ancient Greek writer Hecataeus of Miletus in the 6th century BC. The Taulantii are often reported in the works of ancient writers describing the numerous wars they waged against the Macedonians, the Epirotes, and the ancient Greek colonies on the Illyrian coast.[5] They are mentioned, for instance, by Thucydides, Polybius, Diodorus Siculus, Titus Livius, Pliny the Elder and Appian.[4]

The term taulantii is connected with the Albanian word dallëndyshe, or tallandushe, meaning "swallow".[6] The name Chelidones also reported by Hecateus is the translation of the name Taulantii as khelīdṓn (χελιδών) means "swallow" in Ancient Greek.[7][8]

According to a mythological tradition reported by Appian (2nd century AD), the Taulantii were among the South-Illyrian tribes that took their names from the first generation of the descendants of Illyrius, the eponymous ancestor of all the Illyrian peoples.[9][10][11]

Geography

The Taulantii lived on the southeastern Adriatic coast of southern Illyria (modern Albania), dominating at various times much of the plain between the Drin and the Aous.[12] In earlier times the Taulantii inhabited the northern part of the Drin river;[13] later they lived in the sites of Dyrrah and Apollonia.[8][13]

The extension of the Taulantii to the limits of the Apollonian territory is not very clear in the data provided by Pseudo-Skylax. The southern border of the Taulantii was likely the Seman river, while the northern border was marked by the Mat river. Livy and Pliny located them in the same place, but according to Ptolemy, Aulon (Vlorë) was in Taulantian territory, which implies an extension of this people towards the south including the territory of Apollonia. Such a southward extension was not possible before the end of the Roman civil wars.[14]

History

i n t h e 3rd – 2nd

c e n t u r i e s B C E

The Taulantii are one of the most anciently known Illyrian group of tribes.[3] Taulantian settlement at the site of Dyrrah is estimated to have happened not later than the 10th century BC. After their occupation of the site, Illyrian tribes most likely left the eastern coast of the Adriatic for Italy departing from the region of Dyrrah for the best crossing to Bari, in Apulia.[15][16] When they settled in the area of Dyrrah, it seems that the Taulantii replaced the previous inhabitants, the Bryges.[15][17] According to another tradition the Taulantii replaced the Parthini, who were pushed more inland loosing their coastal holdings.[18]

About the 9th century BC the Liburni expanded their dominion southwards, and took possession of the site expelling the Taulantii.[15][17] In that period the Taulantii expanded southwards and controlled the plain of Mallakastër reaching as far as the mouth of the Aous.[19] Friendly relationships were created between Corinthians and certain Illyrian tribes.[20] In the 7th century BC the Taulantii invoked the aid of Corinth and Corcyra in a war against the Liburni.[21][17][20] After the defeat and expulsion of the Liburni from the region, the Corcyreans founded in 627 BC on the Illyrian mainland a colony, mixing with the local population and establishing the Greek element to the port. The city was called Epidamnos-Dyrrhachion, thought to have been the names of two barbarian/Illyrian rulers of the region.[16][21][22] The double name was determined by the presence of a pre-existing Illyrian settlement presumably located on the hills (Epidamnos), while the plain, formerly occupied by a lagoon communicating with the sea, provided favorable conditions that crated a natural harbor (Dyrrachion). The Greek colony was therefore founded in a territory that corresponded to a narrow promontory surrounded by the sea that gave the city the appearance of an island.[23]

A flourishing commercial centre emergend and the city grew rapidly.[24][21] Business relations with the Illyrians of the hinterland were conducted by the poletes (a magistrate).[21] The Taulantii continued to play an important role in Illyrian history between the 5th and 4th–3rd centuries BC. They significantly influenced the affairs of the city, especially in the internal conflicts between aristocrats and democrats. When the democrats seized power, their opponents (allies of the Corcyreans) sought help from the Illyrians. In 435 the Illyrians besieged the city in strength, and through the occupation of the surrounding region, they caused much damage to the economy of the city.[24]

When describing the Illyrian invasion of Macedonia ruled by Argaeus I, somewhere between 678–640 BC, the historian Polyaenus (fl. 2nd-century CE) recorded the supposed oldest known king in Illyria, Galaurus or Galabrus, a ruler of the Taulantii who reigned in the latter part of the 7th century BC.[14][25][26] However nothing guarantees the authenticity of Polyaenus' passage.[26] In the well attested historical period, the Taulantian kingdom seems to have reached its apex during Glaucias' rule, in the years between 335 BC and 302 BC.[27][28][29] After Glaucias' rule, the Taulantian territory likely were absorbed partly by Pyrrhus in the Epirotan state and partly by other Illyrian realms established in southern Illyria.

Culture

Taulantian dynasty

The following names are recorded in ancient sources as Taulantian chieftains and/or Illyrian kings:[32][25][33][14]

- Galaurus or Galabrus (latter part of the 7th century BC), the oldest known Illyrian king, recorded by Polyaenus (fl. 2nd-century CE), but nothing guarantees the authenticity of Polyaenus' passage

- Pleuratus I (fl. c. 345 – 344 BC)

- Glaucias (fl. c. 335 – 302 BC), who fought against Alexander the Great and raised Pyrrhus of Epirus, briefly installing him on the throne.

The Illyrian king Monounios, who mintend his own silver staters bearing the king's name and the symbol of Dyrrhachion from about 290 BC, is considered the successor of Glaucias,[34] and probably his son.[35] Their realm also included the southern part of the kingdom of Agron and Teuta.[34]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Illyria & Illyrians. |

References

- James R. Ashley, The Macedonian Empire, McFarland, 2004, p. 172.

- Hammond 1966, p. 247.

- Katičić 1976, p. 158.

- Mesihović & Šačić 2015, p. 44: "Taulanti se ubrajuju među narode koji su najviše obilježili ilirsku historiju, te su tako našli svoje mjesto u brojnim radovima klasičnih historičara poput Tukidida, Polibija, Diodora Sicilijanskog, Tita Livija, Plinija Starijeg, Apijana i drugih. Njihovo ime se veže za lastavice, tako da bi Taulanti u slobodnom prevodu bili „narod lastavica“."

- Stipčević 1989, p. 35.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 244: "Names of individuals peoples may have been formed in a similar fashion, Taulantii from 'swallow' (cf. the Albanian tallandushe) or Erchelei the 'eel-men' and Chelidoni the 'snail-men' [sic]."

- Šašel Kos 1993, p. 119.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 98.

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 213: "The tribes which took their names from the first generation of Illyrius' descendants belong mostly to the group of the so-called South-Illyrian tribes: the Taulantii, the Parthini, the Enchelei, the Dassaretii".

- Šašel Kos 2004, p. 502.

- Mesihović & Šačić 2015, pp. 23–24.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 97–98.

- Stipčević 1974, p. 31.

- Jaupaj 2019, p. 81.

- Hammond 1982, p. 628.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 110–111.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 111.

- Stocker 2009, p. 217

- Hammond, N. G. L. (1997). "Prehistory and Protohistory". Epirus: 4000 Years of Greek Cilization and Culture. Ekdotike Athenon: 42. ISBN 9789602133712.

This enterprising and martial people expanded again after 800 B.C.... the Taulantioi seized the Malakastra plain and reached the mouth of the Aoous

- Stallo 2007, p. 29.

- Hammond 1982, p. 267.

- Sassi 2018, pp. 942, 951, 952

- Sassi 2018, pp. 942–943

- Wilkes 1992, p. 112.

- Hammond & Griffith 1972, p. 21.

- Cabanes 2002, p. 51.

- Hammond 1966, p. 253.

- Dzino 2014, p. 49.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 112, 122–126.

- Polomé 1983, p. 537: "The old kingdom of Illyria, south of Lissos, covered the territory of several tribes who shared a common language, apparently of Indo-European stock: the Taulantii, on the coast, south of Dyrrachium; the Parthini, north of this town; the Dassaretae, inland, near Lake Lychnidos and in the Drin valley; north of them were the Penestae; in the mountains, an older group, the Enchelei, lingered on." [footnote 84:] "In the oldest sources, the term 'Illyrian' appears to be restricted to the tribes of the Illyricum regnum (PAPAZOGLU, 1965). Linguistically, it can only legitimately be applied to the southeastern part of the expanded Roman Illyricum; the Delmatae and the Pannonii to the northwest mus have constituted an ethnically and linguistically distinct group (KATIČIĆ, 1968: 367-8)."

- Cambi, Čače & Kirigin 2002, p. 117: "The Illyrian peoples, mentioned in the sources in which the events concerning the Illyrian kingdom are narrated – to name the most outstanding – are the Taulantii, Atintani, Parthini, Enchelei, Penestae, Dassaretii, Ardiaei, Labeates, and the Daorsi. All of these peoples were conceivably more or less closely related in terms of culture, institutions and language. Many of them may have had their own kings, some of whom attained great power and actively took part in the struggle for power in the Hellenistic world. The name “Illyrian” must have carried enough prestige at the time of the rise of the Ardiaean dynasty within the Illyrian kingdom that it was imposed at a later date, when the Romans conquered Illyria and the rest of the Balkans, as the official name of the future provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia."

- Cabanes 2002, p. 90.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 122, 124, 336.

- Picard 2013, p. 82.

- Šašel Kos 2003, p. 149

Bibliography

- Boardman, John; Sollberger, E. (1970). The Cambridge Ancient History. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 629. ISBN 978-0-521-22496-3.

- Cabanes, Pierre (2002) [1988]. Dinko Čutura; Bruna Kuntić-Makvić (eds.). Iliri od Bardileja do Gencia (IV. – II. stoljeće prije Krista) [The Illyrians from Bardylis to Gentius (4th – 2nd century BC)] (in Croatian). Translated by Vesna Lisičić. Svitava. ISBN 953-98832-0-2.

- Cambi, Nenad; Čače, Slobodan; Kirigin, Branko, eds. (2002). Greek influence along the East Adriatic Coast. Knjiga Mediterana. 26. ISBN 9531631549.

- Dzino, Danijel (2014). "'Illyrians' in ancient ethnographic discourse". Dialogues d'histoire ancienne. 40 (2): 45–65. doi:10.3917/dha.402.0045.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1966). "The Kingdoms in Illyria circa 400-167 B.C.". The Annual of the British School at Athens. British School at Athens. 61: 239–253. doi:10.1017/S0068245400019043. JSTOR 30103175.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière; Griffith, Guy Thompson (1972). A history of Macedonia. 2. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198148142.

- Hammond, N. G. L. (1982). "Illyris, Epirus and Macedonia". In John Boardman; N. G. L. Hammond (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries B.C. III (part 3) (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521234476.

- Hammond, N. G. L. (1994). "Illyrians and North-west Greeks". The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 6: The Fourth Century BC. Cambridge University Press: 422–443. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521233484.017. ISBN 9780521233484.

- Jaupaj, Lavdosh (2019). Etudes des interactions culturelles en aire Illyro-épirote du VII au III siècle av. J.-C (Thesis). Université de Lyon; Instituti i Arkeologjisë (Albanie).

- Katičić, Radoslav (1976). Ancient Languages of the Balkans. Mouton. p. 158.

- Mesihović, Salmedin; Šačić, Amra (2015). Historija Ilira [History of Illyrians] (in Bosnian). Sarajevo: Univerzitet u Sarajevu [University of Sarajevo]. ISBN 978-9958-600-65-4.

- Papazoglu, Fanula (1978). The Central Balkan Tribes in pre-Roman Times: Triballi, Autariatae, Dardanians, Scordisci and Moesians. Amsterdam: Hakkert.

- Picard, Olivier (2013). "Ilirët, kolonitë greke, monedhat dhe lufta". Iliria (in Albanian). 37: 79–97. doi:10.3406/iliri.2013.2428.

- Polomé, Edgar C. (1983). "The Linguistic Situation in the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire". In Wolfgang Haase (ed.). Sprache und Literatur (Sprachen und Schriften [Forts.]). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 509–553. ISBN 3110847035.

- Šašel Kos, Marjeta (1993). "Cadmus and Harmonia in Illyria". Arheološki Vestnik. 44: 113–136.

- Šašel Kos, Marjeta (2004). "Mythological stories concerning Illyria and its name". In P. Cabanes; J.-L. Lamboley (eds.). L'Illyrie méridionale et l'Epire dans l'Antiquité. 4. pp. 493–504.

- Šašel Kos, Marjeta (2003). "The Roman conquest of Dalmatia in the light of Appian's Illyrike". In Urso, Gianpaolo (ed.). Dall'Adriatico al Danubio: l'Illirico nell'età greca e romana : atti del convegno internazionale, Cividale del Friuli, 25-27 settembre 2003. I convegni della Fondazione Niccolò Canussio. ETS. pp. 141–166. ISBN 884671069X.

- Sassi, Barbara (2018). "Sulle faglie il mito fondativo: i terremoti a Durrës (Durazzo, Albania) dall'Antichità al Medioevo" (PDF). In Marco Cavalieri; Cristina Boschetti (eds.). Multa per aequora. Il polisemico significato della moderna ricerca archeologica. Omaggio a Sara Santoro. Fervet Opus 4 (in Italian). 2, part VII: Archeologia dei Balcani. Presses Universitaires de Louvain, with the support of Centre d’étude des Mondes antiques (CEMA) of the Université catholique de Louvain. ISBN 978-2-87558-692-6.

- Stallo, Jennifer (2007). Isotopic Study of Migration: Differentiating Locals and Non-Locals in Tumulus Burials from Apollonia, Albania (Thesis). University of Cincinnati.

- Stipčević, Aleksandar (1974). The Illyrians: history and culture (1977 ed.). Noyes Press. ISBN 978-0815550525.

- Stipčević, Aleksandar (1989). Iliri: povijest, život, kultura [The Illyrians: history and culture] (in Croatian). Školska knjiga. ISBN 9788603991062.

- Stocker, Sharon R. (2009). Illyrian Apollonia: Toward a New Ktisis and Developmental History of the Colony.

- Wilkes, John J. (1992). The Illyrians. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-19807-5.