Dassaretii

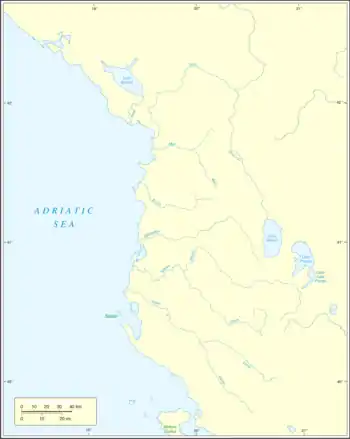

The Dassaretii (alternatively, Dassaretes, Dassaretae, Dassaretai, Dassaretioi or Dassareti) (Ancient Greek: Δασσαρῆται, Δασσαρήτιοι, Latin: Dassaretae, Dassaretii) were an Illyrian people that lived in the inlands of southern Illyria (modern Albania and North Macedonia).[1] Their territory included the entire region between the rivers Asamus and Eordaicus (whose union forms the Apsus), the plateau of Korça locked by the fortress of Pelion and, towards the north it extended to Lake Lychnidus up to the Black Drin. They were directly in contact with the regions of Orestis and Lynkestis of Upper Macedonia.[2] Their chief city was Lychnidos, located on the edge of the omonym lake.[3]

One of the most important settlements in their territory was established at Selcë e Poshtme near the western shore of Lake Lychnidus, where the Illyrian Royal Tombs were built.[4] The Dassaretii were one of the most prominent Illyrian tribes of southern Illyria,[5][6] which formed the ancient Illyrian kingdom that was established in this region.[7] According to a number of modern scholars the dynasty of Bardylis, which is the first attested Illyrian dynasty, was Dassaretan.[8] From the 3rd century BC onwards they were attested as one of the largest Illyrian tribes of the region, and in different periods they changed their rulers, being alternatively under the Illyrian (Ardiaean/Labeatan) kingdom, the Madedonian kingdom and the Roman Republic.[9] In Hellenistic times the Dassaretii minted coins bearing the inscription of their ethnicon.[10]

Etymology

The tribal name Dassaret- is of Illyrian origin,[12][13][14] stemming from Illyrian *daksa/dassa ("water, sea") attached to the suffix -ar. It is related to Illyrian personal names Dazos and Dassius and is also reflected in the toponym of Daksa island and the river Ardaxanos, which is mentioned by Polybius (2nd century BC) in the hinterland of modern Durrës and Lezhë.[15] The tribal name Sessarethes (or Sesarethii), mentioned for the first time by Hecataeus (6th century BC) as an Illyrian tribe holding the city of Sesarethus in the territory of the Illyrian Taulantii, seems to have been a variant of Dassaretes. The variant Sesarethii is also mentioned by Strabo (1st century BC – 1st century AD) as an alternative name of the Enchelei.[13][16]

The tribal name Dexaroi, recorded as a Chaonian tribe by Stephanus of Byzantium (6th century AD) citing Hecataeus, has likely the same root as the Illyrian Dassaretii.[15][17] The hypothesis that equates the Dexaroi with the Dassaretii still remains uncertain.[18] According to a mythological tradition reported by Appian (2nd century AD), the Dassaretii were among the South-Illyrian tribes that took their names from the first generation of the descendants of Illyrius, the eponymous ancestor of all the Illyrian peoples.[19][20][21] The Illyrian Dassaretii are often mentioned by Polybius (The Histories) and Livy (Ab Urbe Condita Libri) in their accounts of the Illyrian Wars and Macedonian Wars. They are also mentioned by Strabo (Geographica. VII. p. 316), Appian (Illyrike. 1), Pomponius Mela (De situ orbis libri III. II. 3), Pliny (Natural History. III. 23), Ptolemy (Geography. p. 83) and Stephanus of Byzantium (Ethnica. "Δασσαρῆται"). Their name appears also on coins of the Hellenistic period bearing the inscription ΔΑΣΣΑΡΗΤΙΩΝ.[10]

Geography

i n t h e 3rd – 2nd

c e n t u r i e s B C E

The territory inhabited by the Dassaretii has been documented in literary sources dating from the Roman period. The Dassaretii were located between the tribes of Parthini (who dwelled in the Shkumbin valley) and Atintanes (who inhabited in the mountain ranges between Asamus and Aous rivers). The extent of the territory of Dassaretii seems to have been considerable, since it included the entire region between the rivers Asamus and Eordaicus (whose union forms the Apsus), the plateau of Korça locked by the fortress of Pelion and, towards the north it extended to Lake Lychnidus up to the omonym city.[22][23][5][24][25] Although Lake Ohrid and Lake Prespa are usually called "Dassaretan Lakes", only Ohrid remained part of Dassaretan territory, while the region of Prespa became part of Macedon when Philip II annexed it after its victories against the Illyrians.[11][26] The territory inhabited by Dassaretii was thus a central area of southern Illyria, directly in contact with the regions of Orestis and Lynkestis of Upper Macedonia.[22][5][27]

Livy (1st century BC) reports that following the victory of 167, the Roman Senate decided to give freedom to "Issenses et Taulantios, Dassaretiorum Pirustas, Rhizonitas, Olciniatas", rewarded because they abandoned the Illyrian kingdom of Gentius a little before his defeat. For a similar reason Daorsi too gained immunitas, while half of the tax had to be paid by "Scodrensibus et Dassarensibus et Selepitanis ceterisque Illyriis" ("the inhabitants of Scodra, Dassarenses and Seleptani, as well as by other Illyrians").[28] Some scholars have suggested that Livy's material follows exclusively Polybius (2nd century BC). However, it is contradicted by the fact that Lyvian texts reports Illyrian toponyms and ethnonyms principally located in the core of the Illyrian kingdom (Ardiaean–Labeatan dynasty), north of Via Egnatia, except for Taulantii and Dassaretii, a situation different from that of the 2nd century BC. An evident relation between the Pirustae and Dassaretii appears in the text, but the Pirustae are thought to have been located much further north of Dassaretii. This could be explained by the possibility that the Pirustae had various locations in different periods, by the existence of two tribes with the same name or similar names, or by an unknown and hypothetical expansion of the Dassaretii to the north.[29]

Settlements

Polybius mentions Pelion, Antipatreia, Chrysondyon, Gertous and Creonion as Dassaretan cities in the 2nd century BC. The precise location seems to have been found however only for Antipatreia, identified with modern Berat.[30][31][16] The city of Lychnidos located on the edge of the omonym lake, was the chief city of the Illyrian tribe of Dassaretii.[32][33][34] The settlement of Hija e Korbit in the Korça plain at the Devoll river (ancient Eordaicus) has been probably one of the relevant commercial and military sites of the Illyrian Dassaretii.[35] One of the most prominent settlements in the region of Illyrian Dassaretii was established at Selcë e Poshtme, where the Illyrian Royal Tombs were built.[23][36]

Culture

Language

The idiom spoken by the tribe of Dassaretii belonged to the southeastern Illyrian linguistic area.[37][38]

Religion

Several cult-objects with similar features are found in different Illyrian regions, including the territory of the Illyrian tribes of Dassaretii, Labeatae, Daorsi, and comprising also the Iapodes. In particular, a 3rd-century BC silvered bronze belt buckle, found inside the Illyrian Tombs of Selça e Poshtme near the western shore of Lake Lychnidus in Dassaretan territory, depicts a scene of warriors and horsemen in combat, with a giant serpent as a protector totem of one of the horsemen; a very similar belt was found also in the necropolis of Gostilj near the Lake Scutari in the territory of the Labeatae, indicating a common hero-cult practice in those regions. Modern scholars suggest that the iconographic representation of the same mythological event includes the Illyrian cults of the serpent, of Cadmus, and of the horseman, the latter being a common Paleo-Balkan hero.[36][39]

The cult of Artemis under the epithet Άγρότα, Agrota was practiced in southern Illyria, in particular during the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial times. The worship of Artemis Agrota, "Artemis the Huntress", is considered an Illyrian indigenous cult since it was widespread only in southern Illyria, stretching from the Illyrian Dassaretan territory up to Dalmatia, including also the territory of Apollonia. In later Roman times, the cult of Diana Candaviensis, which has been interpreted as "Artemis the Huntress", was practiced up to the region north of Lake Shkodra (ancient lacus labeatis), including also the territory of the Docleatae.[40]

Politics

Illyrian Realm

Dassaretii were one of the tribes forming the ancient Illyrian kingdom that was established in the region of southern Illyria.[37][38][41] Ancient sources and modern scholars hold that one of the first kingdoms established in this region was that of the Enchelei. It seems that the weakening of the kingdom of Enchelae resulted in their assimilation and inclusion into a newly established Illyrian realm at the latest in the 5th century BC, marking the arising of the Dassaretii, who appear to have replaced the Encheleans in the lakeland area (Ohrid and Prespa).[42][39]

According to a historical reconstruction, Bardylis founded a powerful Illyrian dynasty among the Dassaretii in the 5th century BC,[43][6][44] and established a realm centered in their territory that comprised the area along Lychnidus and east to the Prespa Lakes, which was called "Dassaretis" later in Roman times.[45][note 1] A fragment of Callisthenes (c. 360 – 327 BC) which places Bardylis' realm between Molossis and Macedonia, well determines the position of that Illyrian kingdom in the area of Dassaretis.[48] Bardylis' expansion in Upper Macedonia and Molossis, and his son Cleitus' revolt at Pelion in Dassaretis against Alexander the Great make this localization of the core of their realm even more plausible.[49][50][51]

The establishment of a tribal realm centered in the rich region of the Illyrian Dassaretii seems supported also by numismatic and epigraphic evidence.[52][24][53][35] The Illyrian Royal Tombs of Selca e Poshtme are located in the Illyrian Dassaretan region.[23] The site of Selcë was in the past a flourishing economical centre more developed than the surroundings because it occupied a predominant position inside the region currently called Mokër, and because it controlled the road which led from the Adriatic coasts of Illyria to Macedonia.[54]

A helmet reporting the inscription of the name of the Illyrian king Monunius was found in the area of lake Lychnidus in the territory of the Illyrian tribe of Dassaretii. It has been interpreted as a possible component of the equipment of a royal special force, suggesting also a financial activity of this king.[24] Dating back to the 3rd century BC, the inscriptions of Monunius are considered the oldest known in the area.[55]

Before the year 229 the Illyrian tribe of Dassaretii had been under the rule of the Illyrian kingdom of the Ardiaei, and they controlled the mountain passes eastwards over the Pindus on the border with Macedon.[56] The retreat to the north and in later times the destruction of the Illyrian kingdom highlighted numerous communities in southern Illyria – including the Dassaretii – that were organized in koina, as evidenced by historical sources, coins and epigraphic material.[57]

Illyrian dynasty

The following is a list of the members of Bardylis' Illyrian dynasty recorded as such in ancient sources, whose realm was centered in the territory of the Dassaretii as claimed by a number of modern scholars:[8]

- Bardylis I (c. 448 – 358 BC)

- Cleitus (fl. c. 335 BC), son of Bardylis I

- Bardylis II (fl. c. 300 BC), son of Cleitus

Grabus I (fl. c. 5th century BC) and Grabus II (fl. c. 357 – 356 BC), who most likely was the son of the former, should also have ruled in the same region of southern Illyria,[58] however there are not enough historical elements to determine whether or not they were of the same dynasty as Bardylis I.[59] The same observation applies in the case of Monunius I (fl. c. 280 BC) and Mytilus (fl. c. 270 BC).[60]

Roman times institutions

Ancient historian Polybius (fl. 2nd century BC) describes peoples of Illyria, like the Dassaretae and the Ardiaei, using the term ethnos, with the meaning of "tribes" within wider national units.[61] After defeating the Macedonians in 196 BC, Roman consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus assigned to the Illyrian (Labeatan) king Plauratus, son of Skerdilaidas, the regions of the Parthini and Lychnis, which were previously occupied by Philip V of Macedon, and the territory of the Dassaretii was also likely detached from Macedon.[62] Thus, after the Roman campaigns in Macedonia the Dassaretii were declared independent as Roman allies, like the Orestae, and they established autonomous political entities under the Roman protectorate.[63]

The Dassaretioi were mentioned in Imperial times in many inscriptions as either having an executive power or as dedicants. The official of the highest rank was, most likely, the strategos, whose seat seems to have been located in Lychnidos.[64] However, the Dassaretioi were not mentioned in a single inscription together with the polis of Lychnidos. This indicates that from the Hellenistic period they seem to have been separate political entities. It has been suggested that the tribe of Dassaretioi and the city of Lychnidos might have formed some kind of political confederation (similar to a koinon) based on the unification of various tribes or various towns and villages. This type of political organisation were quite widespread in the Balkans during the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Some of these confederations survived until Imperial times, such as that of the Bylliones.[63]

Stephanus of Byzantium (fl. 6th century AD) describes the Dassaretai as an Illyrian ethnos and does not associate them with a city. He seems to have used the term ethnos to describe the Dassaretan community in conformation to Anthony Snodgrass' definition: “In its purest form the ethnos was no more than a survival of the tribal system into historical times: a population scattered thinly over a territory without urban centres, united politically and in customs and religion, normally governed by means of some periodical assembly at a single centre, and worshipping a tribal deity at a common religious centre”. Snodgrass presents indeed the ethnos as the prehistoric precursor of the polis describing it “no more than a survival of the tribal system into historical times”.[65]

Economy

The region of the Illyrian tribe of Dassaretii bordered the regions of Macedonia and Molossia. Including the valleys of Osum and Devoll rivers, stretching to the east into the Korçë Plain, and comprising the area around lake Ohrid, the Illyrian Dassaretan region was rich in natural resources and was located in a strategic geographical position that aroused the political wishes of the neighbours and the interest of the Greek merchants.[52] In antiquity, as the authors of that time informs, the Dassaretan territory was known for its very fertile countryside, with a developed agricultural economy. An example is the account about the Roman consul Sulpicius, who during the Second Macedonian War in 199 BC, passed through the territory of the Dasaretii and supplied his army with the products offered by that region, without the resistance of the locals.[66] The prosperous site of Selcë was important in the region, because it occupied a prominent military and commercial position and predominated in the area near Via Egnatia, which was established in Roman times. Some of its natural resources were the stone quarries. The area was likely also close to the silver mines of Damastion.[23] The Dassaretii minted coins in Hellenistic times. Coins bearing the inscription ΔΑΣΣΑΡΗΤΙΩΝ (DASSARETION) have been found in the region of Lake Lychnidus.[10] In Roman times the Dassaretii may have practiced transhumance in southern Illyria.[16]

Notes

- There is also another historical reconstruction that considers Bardylis a Dardanian ruler, who during the expansion of his dominion included the region of Dassaretis in his realm, but this interpretation has been challenged by historians who consider Dardania too far north for the events involving the Illyrian king Bardylis and his dynasty.[43][46][47]

References

- Jaupaj 2019, pp. 78–80; Kunstmann & Thiergen 1987, p. 112; Castiglioni 2007, p. 174; Erdkamp 1998, p. 144; Siewert 2003, p. 55; Polomé 1983, p. 537; Cabanes 2002, pp. 27, 195; Papazoglu 1978, p. 213; Stipčević 1989, p. 28; Winnifrith 2002, pp. 46, 214; Ujes 2002, p. 106; Weber 1989, p. 81; McInerney 1999, p. 24; Cambi, Čače & Kirigin 2002, p. 11; Zindel et al. 2018, p. 280; Eckstein 2008, pp. 53, 412; Šašel Kos 2005, p. 913; Mesihović & Šačić 2015, p. 47.

- Cabanes 1988, p. 49; Castiglioni 2007, p. 174; Eckstein 2008, p. 53; Erdkamp 1998, p. 144; Jaupaj 2019, p. 80.

- Fasolo 2009, p. 606; Šašel Kos 2005, p. 913; Ujes 2002, p. 105.

- Castiglioni 2010, pp. 93–94; Garašanin 1976, pp. 278–279

- Kunstmann & Thiergen 1987, p. 112: "Die Dassaretae waren einer der bedeutendsten illyrischen Stämme, dessen Siedelgebiet sich von der Stadt Lychnidos am gleichnamigen See bis zur Stadt Antipatria am unteren Apsos erstreckte."

- Castiglioni 2007, p. 174: "Bardyllis, the king of the Dassaretii, one of the most powerful Illyrian tribes established on the border between Macedonia and Epirus."

- Polomé 1983, p. 537; Cambi, Čače & Kirigin 2002, p. 117; Mesihović 2014, p. 219.

- Toynbee 1969, p. 116; Mortensen 1991, pp. 49–59; Cabanes 2002, pp. 50–51, 56, 75; Castiglioni 2010, p. 58; Lane Fox 2011, p. 342; Cambi, Čače & Kirigin 2002, p. 106; Mesihović & Šačić 2015, pp. 129–130.

- Papazoglu 1988, p. 74: "Sur la frontière occidentale de la Macédonie, les grandes tribus illyriennes des Dassarètes et des Pénestes, situées entre les royaumes de Macédonie et d'Illyrie, avaient souvent changé de maître."

- Verčík et al. 2019, p. 44: "in the Hellenistic period when they were responsible for coin emissions bearing the name of the Dassaretioi (ΔΑΣΣΑΡΗΤΙΩΝ)." p. 46: "Dassaretioi, an Illyrian tribe that minted coins in Hellenistic times"

- Papazoglu 1988, p. 75.

- Kunstmann & Thiergen 1987, p. 112.

- Ujes 2002, p. 106: "Les noms des souverains des mines sont tant d'origine illyrienne (Dassarètes ou Sessarèthes) que thrace (Périsadyes). Si l'on admettait que ces noms tribaux fournissent un indice de la position géographique des tribus en question, cela pourrait indiquer que les mines se trouvaient dans une zone de contact entre des tribus d'origine illyrienne et d'autres d'origine thrace".

- Weber 1989, p. 81: "The spelling of Dassarentii resembles two known Illyrian names, Dassaretae and Daesitiates. Of the two, Dassaretae is probably the tribe Livy meant to describe...

- Kunstmann & Thiergen 1987, pp. 110–112.

- Winnifrith 2002, p. 46: "Among Illyrian tribes, apart from the Enchelidae we find the Taulantii, Bylliones, Parthini and Bryges; other Illyrian tribes lived north of the River Shkumbin, as indeed did some of the Taulantii, since they were the barbarians who threatened Epidamnus. There is also a rather mysterious tribe called Sesarethi; they too may give their name to Dassaretis, although in what may be another case of transhumance the Dassaretae in Roman times are found near Berat." p. 214: "Dassaretae, Illyrian tribe"

- Toynbee 1969, pp. 107-108: "For instance, the description of a Chaonian as being a Peukestos, and the mention of another subdivision of the Khaones named the Dexaroi, are evidence that the Khaones had been Illyrian-speakers originally, since the name 'Peukestos' is identical with that of the Apulian Peuketioi, while the name 'Dexaroi' looks like a variant of the name 'Dassaretioi', which was borne by an Illyrian people whose territory extended from the shores of Lake Okhrida (Lykhnidos) south-south-westwards to the upper valley of the River Uzúmi, which joins the Devol to form the Semeni (Apsos). Above all, the most prominent mountain in Epirus, Mount Tomaros or Tmaros, which overhangs the Yannina basin, bears the same name as the most prominent mountain in southern Illyria, the Mount Tomaros that divides the Uzúmi valley from the Devol (Eordaïkos) valley."

- Kaljanac 2010, p. 56

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 213: "The tribes which took their names from the first generation of Illyrius' descendants belong mostly to the group of the so-called South-Illyrian tribes: the Taulantii, the Parthini, the Enchelei, the Dassaretii".

- Šašel Kos 2004, p. 502.

- Mesihović & Šačić 2015, pp. 23–24.

- Cabanes 1988, p. 49: "ce sont les Dassarètes qui sont le premier ethnos illyrien qui avoisine avec les Orestes" p. 64: "Entre Parthins et Atintanes, vers l’Est s’étend le pays des Dassaretes, dont l’étendue paraît considérable, puisqu’il comprend toute la région comprise entre l’Osum et le Devoll, dont la réunion forme l’Apsus (l’actuel Seman), le plateau de Korça verrouillé par la forteresse de Pélion et, vers le Nord la Dassarétide s’étend jusqu’au lac l’Ohrid (121). C’est certainement une zone centrale de l’Illyrie méridionale, celle qui est aussi la plus directement en contact avec les régions de Haute-Macédoine, notamment avec l’Orestide et la Lyncestide."

- Castiglioni 2010, pp. 93–94: "Selcë appartenait géographiquement, au IIIe siècle av. J.-C., à la région illyrienne appelée Dassarétide, territoire comprenant les vallées de l’Osum et du Devoll et s’étendant vers l’est dans les plateaux de Kolonje et de Korçe, et dans la zone autour du lac de Pogradec... Il ne fait aucun doute que cette localité devait correspondre à une agglomération d’une certaine importance, en vertu à la fois desa position stratégique (du point de vue militaire et commercial puisqu’elle occupaitune place prédominante près du parcours de la future Via Egnatia) et de ses ressources naturelles (les carrières de pierre et la proximité des mines d’argent du Damastion). La richesse de sa nécropole ne fait du reste que confirmer cette impression. En particulier, la profusion d’objets précieux de la sépulture n°3 reflète une position sociale très élevée du défunt, qui fut sans doute un notable de la cité. Les reliefs représentant des armes sur la façade monumentale du tombeau, ainsi que le combatfiguré sur le fermoir de ceinture, affichent un caractère explicitement militaire: il devait donc s’agir d’un chef aux fortes prérogatives guerrières, orgueilleux de sa préé-minence et désireux d’en faire un généreux étalage."

- Siewert 2003, p. 55: "Ein Helm aus Lychnidos (Ochrid), dem Gebiet der illyrischen Dassareten, mit der Inschrift, gleich lautend wie auf den Münzen, βασιλέως Μονουνίου, lässt sich als Ausrüstungsteil einer königlichen Spezialtruppe interpretieren, was zu den finanziellen Aktivitäten dieses Königs passt."

- Jaupaj 2019, p. 80: "Les spécialistes sont aujourd’hui d’accord pour situer les Dassarètes entre les Parthins au nord-ouest et les Atintanes au sud-ouest, dans la région des lacs où se situe le noyau fondateur des Enchéléens, avec la Macédoine sur la frontière orientale. Ce vaste territoire comprend le plateau de Korça, les vallées de l’Osum et du Devoll qui se rejoignent ver l’ouest pour former l’Apsos, l’actuel Seman."

- Stocker 2009, p. 66

- Erdkamp 1998, p. 144: "In the spring of 199 B.C., the Roman army, led by consul Sulpicius, marched into the fertile land of the Dassaretii, an Illyrian people who occupied the region bordering western Macedonia."

- Palazzo 2010, p. 285.

- Palazzo 2010, pp. 286–287.

- Cabanes 1988, p. 64: "Selon Polybe, (122), en dehors de Pélion, les Dassarètes possèdent, au début du IIe siècle avant J.-C., plusieurs villes, Antipatreia (généralement identifiée avec la position privilégiée de la forteresse de Bérat, mais l’unanimité des chercheurs n’est pas réalisée sur cette identification), Chrysondyon, Gertous ou Gerous, Créônion, mais leur localisation reste à établir."

- Zindel et al. 2018, pp. 278, 280: "Unmittelbar westlich von Berat fließt der Osum zwischen fast 200m hohen felsigen Erhebungen und bildet eine Engstelle, womit das bergige Hinterland von der größten Ebene Albaniens, der Muzeka, abgetrennt wird. Die strategische Lage der an der höchsten Stelle auf 187 m ü. M. liegenden Siedlung wurde schon seit der Antike genutzt und die beiden Felshöhen wurden befestigt, wobei der nördliche. Hügel besondere Bedeutung erlangte. Keramikfunde des 7. Jh. v. Chr. bezeugen zunächst eine Besiedlung des Felshügels durch die in den Quellen genannten illyrischen Dassareten. Erstmals wird Berat unter dem Namen Antipatros von Polybios 216 v. Chr. erwähnt.""

- Fasolo 2009, p. 606: "La via proseguiva verso Ohrid, la città sul sito del-l'antica Lychnidòs, antica capitale della tribù illirica dei Dassareti."

- Šašel Kos 2005, p. 913: "Lychnidus (Λυχνιδός, Λυχνίς, Lychnidós, Lychnís), Capital city of the Illyrian Dassaretae (→ Dassaretia) on the → via Egnatia (Str. 7,7,4; It. Ant. 318), modern Ohrid in Macedonia on Lake Ohrid."

- Ujes 2002, p. 105: "Les Dassarètes sont bien attestés dans la région du lac Lychnitis (lac d'Ohrid); Lychnidos, située au bord du lac, était leur ville principale." p. 106: "origine illyrienne (Dassarètes ou Sessarèthes)".

- Zindel et al. 2018, pp. 375–376: "Der Hija e Korbit ist eine Erhebung (ca. 1200 m ü. M.) am Rande der Korça-Ebene, wo sich der Devoll-Fluss in einer Schlucht seinen Weg durch das Randgebirge bahnt. Das rund 20 ha große Hochplateau des Hügels südlich der Schlucht ist von antiken Befestigungsmauern umgeben, die aus grob zugehauenen Kalksteinblöcken in unregelmäßigen Scharen gebildet sind. Eingänge und mögliche Türme sind mangels archäologischer Forschungen und Planaufnahmen noch nicht erfasst. Im Innern lassen sich Reste antiker Bauten, die durch Keramikfunde in hellenistische Zeit datierbar sind, zu erkennen. Bei der Umfassungsmauer wurde erst kürzlich ein Münzdepot aus 618 Prägungen gefunden, die dem ausgehenden 4. und frühen 3. Jh. v. Chr. angehören. Vielleicht handelt es sich um einen in Kriegszeiten versteckten Münzschatz. Jedenfalls konnte von diesem strategisch günstig gelegenen Platz der von > Apollonia an der Adria nach Osten führende Passweg kontrolliert werden. Möglicherweise befand sich am Hija e Korbit eine der militärisch und handelsmäßig wichtigen Städte der illyrischen Dassareten.

- Garašanin 1976, pp. 278–279.

- Polomé 1983, p. 537: "The old kingdom of Illyria, south of Lissos, covered the territory of several tribes who shared a common language, apparently of Indo-European stock: the Taulantii, on the coast, south of Dyrrachium; the Parthini, north of this town; the Dassaretae, inland, near Lake Lychnidos and in the Drin valley; north of them were the Penestae; in the mountains, an older group, the Enchelei, lingered on." [footnote 84:] "In the oldest sources, the term 'Illyrian' appears to be restricted to the tribes of the Illyricum regnum (PAPAZOGLU, 1965). Linguistically, it can only legitimately be applied to the southeastern part of the expanded Roman Illyricum; the Delmatae and the Pannonii to the northwest mus have constituted an ethnically and linguistically distinct group (KATIČIĆ, 1968: 367-8)."

- Cambi, Čače & Kirigin 2002, p. 117: "The Illyrian peoples, mentioned in the sources in which the events concerning the Illyrian kingdom are narrated – to name the most outstanding – are the Taulantii, Atintani, Parthini, Enchelei, Penestae, Dassaretii, Ardiaei, Labeates, and the Daorsi. All of these peoples were conceivably more or less closely related in terms of culture, institutions and language. Many of them may have had their own kings, some of whom attained great power and actively took part in the struggle for power in the Hellenistic world. The name “Illyrian” must have carried enough prestige at the time of the rise of the Ardiaean dynasty within the Illyrian kingdom that it was imposed at a later date, when the Romans conquered Illyria and the rest of the Balkans, as the official name of the future provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia."

- Castiglioni 2010, pp. 93–95.

- Anamali 1992, pp. 135–136.

- Mesihović 2014, p. 219.

- Šašel Kos 2004, p. 500.

- Cabanes 2002, pp. 50–51, 56, 75.

- Mesihović & Šačić 2015, pp. 129–130.

- Lane Fox 2011, p. 342: "Bardylis was king of a realm along Lake Ohrid and east to the two Prespa Lakes, the "Dassaretis" of later topography"; Cabanes 2002, pp. 50–51, 56, 75; Cambi, Čače & Kirigin 2002, p. 106: "However, the fact that Bardylis II is the only attested Illyrian king after Glaucias (Plut., Pyrr. 9.2) does not necessarily mean that he succeeded Glaucias on the throne, but rather that at that time he was the most powerful king in Illyria who could unite the largest number of Illyran tribes under his authority. P. Cabanes thus plausibly suggested that he may have, through his father Clitus, continued the line of Bardylis I, reigning nearer the Macedonian border somewhere in Dassaretia, while the centre of Glaucias' kingdom lay in the Taulantian regions. In one way or another Bardylis II succeeded in his struggle against Macedonia and temporarily brought this part of Illyria, where he prevailed over rivals, to the front."; Toynbee 1969, p. 116: "The two Illyrian rulers Kleitos son of Bardyles, who was perhaps the king of the Dassaretioi, and Glaukias, the king of the Taulantioi, who went to war with Alexander III of Macedon in 335 b.c." [note 3]: "Eventually Kleitos was more powerful of the two allies; it was he who took initia-tive on this occasion (Arrian, Book I; chap. 5, § 1). It is also evident, from the sequel, that Kleitos' country was nearer to the western frontier of Macedon than Taulantia was (ibid., chap. 5, § 4-chap. 6 inclusive). Kleitos had seized the Macedonian frontier fortress Pelion on the upper reaches of the Eordaikos (Devol) River. All this points to Dassaretia's having been Kleitos' country."; Mortensen 1991, pp. 49–59; Mesihović & Šačić 2015, pp. 129–130; Jaupaj 2019, p. 80: "...évolution politique et ethnique de la Dassarétie qui apparaît comme une région riche et vaste, fondatrice de la dynastie de Bardylis, roi du premier royaume illyrien au IVème siècle. M. B. Hatzopoulos soutient la thèse que ce royaume est situé en Dassarétie et plus précisément dans la région des lacs, et il est suivi par F. Papazoglou qui range les Dassarètes parmi les peuples illyriens.".

- Mortensen 1991, pp. 49–59.

- Lane Fox 2011, p. 342: "Their own king Bardylis was king of a realm along Lake Ohrid and east to the two Prespa Lakes, the "Dassaretis" of later topography, not "Dardania", as Hammond postulated"

- Cabanes 2002, p. 56.

- Cabanes 2002, pp. 50–51, 73–75.

- Toynbee 1969, p. 116: "The two Illyrian rulers Kleitos son of Bardyles, who was perhaps the king of the Dassaretioi, and Glaukias, the king of the Taulantioi, who went to war with Alexander III of Macedon in 335 b.c." [note 3]: "Eventually Kleitos was more powerful of the two allies; it was he who took initia-tive on this occasion (Arrian, Book I; chap. 5, § 1). It is also evident, from the sequel, that Kleitos' country was nearer to the western frontier of Macedon than Taulantia was (ibid., chap. 5, § 4-chap. 6 inclusive). Kleitos had seized the Macedonian frontier fortress Pelion on the upper reaches of the Eordaikos (Devol) River. All this points to Dassaretia's having been Kleitos' country."

- Cambi, Čače & Kirigin 2002, p. 106: "However, the fact that Bardylis II is the only attested Illyrian king after Glaucias (Plut., Pyrr. 9.2) does not necessarily mean that he succeeded Glaucias on the throne, but rather that at that time he was the most powerful king in Illyria who could unite the largest number of Illyran tribes under his authority. P. Cabanes thus plausibly suggested that he may have, through his father Clitus, continued the line of Bardylis I, reigning nearer the Macedonian border somewhere in Dassaretia, while the centre of Glaucias' kingdom lay in the Taulantian regions. In one way or another Bardylis II succeeded in his struggle against Macedonia and temporarily brought this part of Illyria, where he prevailed over rivals, to the front."

- Castiglioni 2010, p. 58: "L’apparition sur la scène diplomatique, à partir de 357, de Grabos II dans les ins-criptions que nous venons d’évoquer, encourage à considérer ce dernier comme le successeur de Bardylis et à établir donc le profil d’un solide « royaume » tribal hé-réditaire que les arguments convaincants de M. A. Hatzopoulos situent en Dassarétide, riche région aux frontières avec la Macédoine et la Molossie. La souverainetéd’une seule famille se serait étendue pendant au moins trois quarts de siècle sur unerégion dont les ressources naturelles et l’emplacement stratégique ont suscité lesconvoitises des voisins et l’intérêt des marchands grecs: ce détail, joint au voisinage géographique avec l’un des théâtres de la guerre du Péloponnèse, expliquerait l’im-plication militaire illyrienne et les amitiés athéniennes avec Grabos."

- Picard 2013, p. 82: "Kjo veçanti sjell një argument të rëndësishëm në tezën e historianëve modernë, të cilët në kërkimet për Basileis (mbretërit) ilirë, dallojnë qartë midis mbretërisë së Bardhylit kundërshtar i Filipit të II, të vendosur në malet në lindje dhe mbretërisë së Glaukias dhe asaj të Monunit në bregdet, për të cilat do të flasim sërish."

- Castiglioni 2010, pp. 88–89: "Le premier de ces deux témoignages est un fermoir de ceinture retrouvé dans un tombeau monumental de la localité albanaise de la basse Selce (Selcë e Poshtme) située dans le district de Pogradec, dans la partie orientale du pays, à quelques kilomètres du lac d’Ohrid et à 1010 m au-dessus du niveau de la mer. Ce centre a bénéficié dans le passé d’un essor économique plus florissant par rapport aux plus modestes agglomérations des alentours, grâce à la position centrale et prédominante qu’il occupe à l’intérieur de la contrée actuellement appelée Mokër, et grâce au contrôle de la route qui conduisait des côtes adriatiques de l’Illyrie à la Macédoine, route qui longeait le cours du fleuve Shkumbin (Genusus) et qui passait autrefois par les Gorges de Çervenake. La ville s’étendait sur les terrasses naturelles de la col-line de Gradishte ou Qyteze, dont la partie ouest descend abruptement vers le cours du fleuve Shkumbin."

- Verčík et al. 2019, p. 43.

- Eckstein 2008, p. 53: "Nor did Rome establish connections with the Dassareti, who had been under Ardiaean domination before 229 and who controlled the strategic high passes eastwards over the Pindus Range into Macedon" p. 412: "Dassareti (Illyrian people)"

- Buora & Santoro 2003, p. 28: "La ritirata verso nord e in seguito la distruzione del Regno illirico mise in evidenza un numero considerevole di koinà di cittadini testimoniate dalle iscrizioni (come quelli dei Byllini, dei Balaiti e degli Amanti), dalle monete (come quelli degli Olympi, dei Lisiani, dei Labiati e dei Daorsi) oppure da fonti storiche (come qelli dei Parthini, dei Dassareti e dei Penesti). Questo sistema fu mantenuto in seguito, come struttura politica autonoma funzio-nante sulla base di un'economia autarchica, anche durante l'amministrazione romana (nell'ambito della IV provincia macedone, in seguito Illyricum) fino all'anno 30 a.C."

- Cabanes 2002, pp. 49–55.

- Cabanes 2002, pp. 49–55, 84–90.

- Cabanes 2002, pp. 84–90.

- Gruen 2018, p. 29: "The historian further utilizes the word ethnos to denote peoples normally understood as “tribes”, within larger national units. That would hold for peoples like the Ardiaeans and the Dassaretae of Illyria, the Gallic Insubres, Boii, Senones, and others, the Spanish Olcades, Carpedani, Balearics, Vaccaei, and others, the tribes of Media, those settled along the Euxine, the tribes of Macedonia and of Thrace, those of Libya, and a variety of Italian peoples like the Brutii, Lucanians, and Samnites."

- Papazoglu 1988, p. 74

- Verčík et al. 2019, pp. 44–45.

- Verčík et al. 2019, p. 44

- McInerney 1999, p. 24: "Even so, despite the use of ethnos to describe communities that resided in poleis, there are also instances where Stephanus seems to use ethnos to describe communities that seem to conform to Snodgrass's definition. The Dassaretai are called an Illyrian ethnos, while the Datuleptoi are Thrakian, neither of which is associated with a city. What these tribes share with ethne that also exist as poleis is that each has an identity not tied to a specific set of institutions." p. 19: "The definition suggested by Snodgrass is a good example of such an approach: “In its purest form the ethnos was no more than a survival of the tribal system into historical times: a population scattered thinly over a territory without urban centres, united politically and in customs and religion, normally governed by means of some periodical assembly at a single centre, and worshipping a tribal deity at a common religious centre.” Here the ethnos is presented as the prehistoric precursor of the polis (“no more than a survival of the tribal system into historical times...”

- Shpuza 2009, p. 92

Bibliography

- Anamali, Skënder (1992). "Santuari di Apollonia". In Stazio, Attilio; Ceccoli, Stefania (eds.). La Magna Grecia e i grandi santuari della madrepatria: atti del trentunesimo Convegno di studi sulla Magna Grecia. Atti del Convegno di studi sulla Magna Grecia (in Italian). 31. Istituto per la storia e l'archeologia della Magna Grecia. pp. 127–136.

- Buora, Maurizio; Santoro, Sara, eds. (2003). Progetto Durrës L'indagine sui Beni Culturali albanesi dell'antichità e del medioevo: tradizioni di studio a confronto. Atti del primo incontro scientifico (Parma-Udine, 19-20 aprile 2002). Antichità Altoadriatiche - AAAD (in Italian). LIII. Editreg. ISBN 9788888018126. ISSN 1972-9758.

- Cabanes, Pierre (1988). Les illyriens de Bardulis à Genthios (IVe–IIe siècles avant J.-C.) [The Illyrians from Bardylis to Gentius (4th – 2nd century BC)] (in French). Paris: SEDES. ISBN 2718138416.

- Cabanes, Pierre (2002) [1988]. Dinko Čutura; Bruna Kuntić-Makvić (eds.). Iliri od Bardileja do Gencia (IV. – II. stoljeće prije Krista) [The Illyrians from Bardylis to Gentius (4th – 2nd century BC)] (in Croatian). Translated by Vesna Lisičić. Svitava. ISBN 953-98832-0-2.

- Cambi, Nenad; Čače, Slobodan; Kirigin, Branko, eds. (2002). Greek influence along the East Adriatic Coast. Knjiga Mediterana. 26. ISBN 9531631549.

- Castiglioni, Maria Paola (2007). "Genealogical Myth and Political Propaganda in Antiquity: the Re-Use of Greek Myths from Dionysius to Augustus". In Carvalho, Joaquim (ed.). Religion and Power in Europe: Conflict and Convergence. Edizioni Plus. ISBN 978-88-8492-464-3.

- Castiglioni, Maria Paola (2010). Cadmos-serpent en Illyrie: itinéraire d'un héros civilisateur. Edizioni Plus. ISBN 9788884927422.

- Eckstein, Arthur M. (2008). Rome Enters the Greek East From Anarchy to Hierarchy in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, 230–170 BC. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-6072-8.

- Erdkamp, Paul (1998). Hunger and the sword: warfare and food supply in Roman Republican wars (264-30 B.C.). Dutch monographs on ancient history and archaeology. 20. Gieben. ISBN 978-90-50-63608-7.

- Fasolo, Michele (2009). "La via Egnatia nel territorio della Repubblica di Macedonia". In Cesare Marangio; Giovanni Laudizi (eds.). Παλαιά Φιλία [Palaià Philía]: studi di topografia antica in onore di Giovanni Uggeri. Journal of Ancient Topography - Rivista di Topografia Antica (in Italian). 4. Mario Congedo editore. pp. 601–612. ISBN 9788880868651.

- Garašanin, Milutin V. (1976). "O problemu starobalkanskog konjanika" [About the Problem of Old Balkan Horseman]. Godišnjak Centra za balkanološka ispitivanja (in Serbo-Croatian). Akademija Nauka i Umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine. 13: 273–283.

- Gruen, Erich S. (2018). "Polybius and Ethnicity". In Miltsios, Nikos; Tamiolaki, Melina (eds.). Polybius and his Legacy. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 13–34. ISBN 978-3-11-058397-7. ISSN 1868-4785.

- Jaupaj, Lavdosh (2019). Etudes des interactions culturelles en aire Illyro-épirote du VII au III siècle av. J.-C (Thesis). Université de Lyon; Instituti i Arkeologjisë (Albanie).

- Kaljanac, Adnan (2010). Juzbašić, Dževad; Katičić, Radoslav; Kurtović, Esad; Govedarica, Blagoje (eds.). "Legenda o Kadmu i problem porijekla Enhelejaca" (PDF). Godišnjak/Jahrbuch. Sarajevo: Akademija Nauka i Umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine. 39: 53–79. ISSN 2232-7770.

- Kunstmann, Heinrich; Thiergen, Peter (1987). Beiträge zur Geschichte der Besiedlung Nord- und Mitteldeutschlands mit Balkanslaven (PDF). O. Sagner.

- Lane Fox, R. (2011). "Philip of Macedon: Accession, Ambitions, and Self-Presentation". In Lane Fox, R. (ed.). Brill's Companion to Ancient Macedon: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Macedon, 650 BC – 300 AD. Leiden: Brill. pp. 335–366. ISBN 978-90-04-20650-2.

- McInerney, Jeremy (1999). The Folds of Parnassos, Land and Ethnicity in Ancient Phokis. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-76160-5.

- Mesihović, Salmedin (2014). ΙΛΛΥΡΙΚΗ (Ilirike) (in Bosnian). Sarajevo: Filozofski fakultet u Sarajevu. ISBN 978-9958-0311-0-6.

- Mesihović, Salmedin; Šačić, Amra (2015). Historija Ilira [History of Illyrians] (in Bosnian). Sarajevo: Univerzitet u Sarajevu [University of Sarajevo]. ISBN 978-9958-600-65-4.

- Mortensen, Kate (1991). "The Career of Bardylis". The Ancient World. 22. Ares Publishers. pp. 49–59.

- Palazzo, Silvia (2010). "Ethne e poleis lungo il primo tratto della via Egnatia: la prospettiva di una fonte". In Antonietti, Claudia (ed.). Lo spazio ionico e le comunitàdella Grecia nord-occidentale: Territorio, società, istituzioni (in Italian). Edizioni ETS. pp. 273–290. ISBN 978-884672849-4.

- Papazoglu, Fanula (1978). The Central Balkan Tribes in pre-Roman Times: Triballi, Autariatae, Dardanians, Scordisci and Moesians. Amsterdam: Hakkert.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Papazoglu, Fanula (1988). Les villes de Macédoine à l'époque romaine (in French). Greece: Ecole française d'Athènes. ISBN 9782869580145.

- Picard, Olivier (2013). "Ilirët, kolonitë greke, monedhat dhe lufta". Iliria (in Albanian). 37: 79–97. doi:10.3406/iliri.2013.2428.

- Polomé, Edgar C. (1983). "The Linguistic Situation in the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire". In Wolfgang Haase (ed.). Sprache und Literatur (Sprachen und Schriften [Forts.]). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 509–553. ISBN 3110847035.

- Šašel Kos, Marjeta (2004). "Mythological stories concerning Illyria and its name". In P. Cabanes; J.-L. Lamboley (eds.). L'Illyrie méridionale et l'Epire dans l'Antiquité. 4. pp. 493–504.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Šašel Kos, Marjeta (2005). "Lychnidus". In Hubert, Cancik; Schneider, Helmuth; Salazar, Christine F. (eds.). Brill's New Pauly, Antiquity, Volume 7 (K-Lyc). Brill's New Pauly. 7. Brill. ISBN 9004122702.

- Shpuza, Saïmir (2009). Aspekte të ekonomisë antike ilire dhe epirote / Aspects of Ancient Illyrian and Epirotic Economy. Iliria. 34. pp. 91–110. doi:10.3406/iliri.2009.1083.

- Siewert, Peter (2003). "Politische Organisationsformen im vorrömischen Südillyrien". In Urso, Gianpaolo (ed.). Dall'Adriatico al Danubio: l'Illirico nell'età greca e romana : atti del convegno internazionale, Cividale del Friuli, 25-27 settembre 2003. I convegni della Fondazione Niccolò Canussio (in German). ETS. pp. 53–62. ISBN 884671069X.

- Stocker, Sharon R. (2009). Illyrian Apollonia: Toward a New Ktisis and Developmental History of the Colony.

- Stipčević, Aleksandar (1989). "Topografija ilirskih plemena" [Topography of Illyrian tribes]. Iliri: povijest, život, kultura [The Illyrians: history and culture] (in Croatian). Školska knjiga. ISBN 9788603991062.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Toynbee, Arnold Joseph (1969). Some problems of Greek history. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192152497.

- Ujes, Dubravka (2002). "Recherche sur la localisation de Damastion et ses mines". Revue numismatique. 6th. 158: 103–129. doi:10.3406/numi.2002.1438.

- Verčík, Marek; Kerschbaum, Saskia; Tušlová, Petra; Jančovič, Marián; Donev, Damjan; Ardjanliev, Pero (2019). "Settlement Organisation In The Ohrid Region". Studia Hercynia (XXIII/1): 26–54.

- Weber, R. J. (1989). "The Taulantii and Pirustae in Livy's Version of the Illyrian Settlement of 167 B. C. : The Roman Record of Illyria". In Deroux, Carl (ed.). Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History. V. Latomus. pp. 66–93. ISBN 978-2-87031-146-2.

- Winnifrith, Tom J. (2002). Badlands-borderlands: a history of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-3201-9.

- Zindel, Christian; Lippert, Andreas; Lahi, Bashkim; Kiel, Machiel (2018). Albanien: Ein Archäologie- und Kunstführer von der Steinzeit bis ins 19. Jahrhundert (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 9783205200109.