Charles de Foucauld

Charles Eugène de Foucauld, Viscount of Foucauld, (15 September 1858 - 1 December 1916), was a cavalry officer in the French Army, then an explorer and geographer, and finally a Catholic priest and hermit who lived among the Tuareg in the Sahara in Algeria. He was assassinated in 1916 and is considered by the Church to be a martyr. His inspiration and writings led to the founding of the Little Brothers of Jesus among other religious congregations. On 27 May 2020, Pope Francis cleared the way for his canonization at a future date.

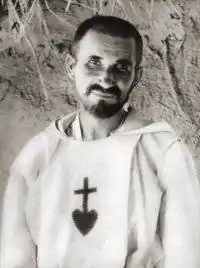

de Foucauld around 1907. | |

| Priest; Mystic; Martyr | |

| Born | Charles Eugène de Foucauld de Pontbriand 15 September 1858 Strasbourg, Second French Empire |

| Died | 1 December 1916 (aged 58) Tamanrasset, French Algeria |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 13 November 2005, Saint Peter's Basilica, Vatican City by Cardinal José Saraiva Martins |

| Feast | 1 December |

| Attributes | Trappist habit |

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

Orphaned at the age of six, Charles de Foucauld was brought up by his maternal grandfather, Colonel Beaudet de Morlet. He joined the Saint-Cyr Military Academy. Upon leaving the Academy he opted to join the cavalry. He thus went to the Saumur Cavalry School, where he was known for his childish sense of humour, whilst living a life of debauchery thanks to an inheritance he received after his grandfather's death. He was assigned to the 4th Hussars Regiment. At the age of twenty-three, he decided to resign in order to explore Morocco by impersonating a Jew. The quality of his works earned him a gold medal from the Société de Géographie, as well as fame following publication of his book "Reconnaissance au Maroc" (1888).

Once back in France, he rekindled his Catholic faith and joined the Cistercian Trappist order on 16 January 1890. Still with the Trappists, he then went to Syria. His quest of an even more radical ideal of poverty, altruism, and penitence, led him to leave the Trappists in order to become a hermit in 1887. He was then living in Palestine, writing his meditations that became the cornerstone of his spirituality.

Ordained in Viviers in 1901,[1] he decided to settle in the Algerian Sahara at Béni Abbès. His ambition was to form a new congregation, but nobody joined him. He lived with the Berbers, adopting a new apostolic approach, preaching not through sermons, but through his example. In order to be more familiar with the Tuareg, he studied their culture for over twelve years, using a pseudonym to publish the first Tuareg–French dictionary. Charles de Foucauld's works are a reference point for the understanding of Tuareg culture.

On 1 December 1916, Charles de Foucauld was assassinated at his hermitage. He was quickly considered to be a martyr and was the object of veneration following the success of the biography written by René Bazin (1921). New religious congregations, spiritual families, and a renewal of eremitic life are inspired by Charles de Foucauld's life and writings.

His beatification process started eleven years after his death, in 1927. It was interrupted during the Algerian War, resumed later, and Charles de Foucauld was declared Venerable on 24 April 2001 by Pope John Paul II, then Blessed on 13 November 2005 by Pope Benedict XVI. On 27 May 2020, the Vatican announced that he would be canonized at a later date.[2]

Biography

Childhood

De Foucauld's family was originally from the Périgord region of France and part of the old French nobility; their motto being "Jamais arrière".(Never behind)[3] Several of his ancestors took part in the crusades,[4] a source of prestige within the French nobility. His great-great-uncle, Armand de Foucauld de Pontbriand, a vicar and first cousin of the archbishop of Arles, Monseigneur Jean Marie du Lau d'Allemans, as well as the archbishop himself, were victims of the September massacres that took place during the French Revolution.[3] His mother, Élisabeth de Morlet, was from the Lorraine aristocracy[3] whilst his grandfather had made a fortune during the revolution as a republican.[5] Élisabeth de Morlet married the viscount Édouard de Foucauld de Pontbriand, a forest inspector, in 1885.[6] On 17 July 1857, their first child Charles was born, and died one month later.[3]

Their second son, whom they named Charles Eugène, was born in Strasbourg on 15 September 1858,[6] in the family house on Place Broglie at what was previously mayor Dietrich's mansion, where La Marseillaise was sung for the first time, in 1792.[3] The child was baptised at the Saint-Pierre-le-Jeune Church (though currently a Protestant church, both faiths coexisted there until 1898) on 4 November of the same year.

A few months after his birth, his father was transferred to Wissembourg. In 1861, Charles was three and a half years old when his sister, Marie-Inès-Rodolphine, was born.[3] His profoundly religious mother educated him in the Catholic faith, steeped in acts of devotion and piety.[3] She died following misscarriage[6] on 13 March 1864, followed by her husband who suffered from neurasthenia, on 9 August.[3] The now orphaned Charles (age 6) and his sister Marie (age 3) were put in the care of their paternal grandmother, viscountess Clothilde de Foucauld, who died of a heart attack shortly afterwards.[6][5] The children were then taken in by their maternal grandparents, colonel Beaudet de Morlet and his wife, who lived in Strasbourg.

The colonel Beaudet de Morlet, alumnus of the École Polytechnique and engineering officer, provided his grandchildren with a very affectionate upbringing.[5] Charles shall write of him : "My grandfather whose beautiful intelligence I admired, whose infinite tenderness surrounded my childhood and youth with an atmosphere of love, the warmth of which I still feel emotionally".[5]

Charles pursued his studies at the Saint-Arbogast episcopal school, and went to Strasbourg high school in 1868.[6] At the time an introvert and short-tempered,[6] he was often ill and pursued his education thanks to private tuition.[3]

He spent the summer of 1868 with his aunt, Inès Moitessier, who felt responsible for her nephew. Her daughter, Marie Moitessier (later Marie de Bondy), eight years older than Charles, became fast friends with him.[6] She was a fervent church-goer who was very close to Charles, sometimes acting as a maternal figure for him.[3]

In 1870 the de Morlet family fled the Franco-Prussian War and found refuge in Bern. Following the French defeat, the family moved to Nancy in October 1871.[3][6] Charles had four years of secular highschool left.[6] Jules Duvaux was a teacher of his,[6][3] and he bonded with fellow student Gabriel Tourdes.[6] Both students had a passion for classical literature,[5] and Gabriel remained, according to Charles, one of the "two incomparable friends" of his life.[5] His education in a secular school developed nurtured patriotic sentiment, alongside a mistrust for the German Empire.[6] His First Communion took place on 28 April 1872, and his confirmation at the hands of Monseigneur Joseph-Alfred Foulon in Nancy followed shortly thereafter.[5]

In October 1873, whilst in a Rhetoric class, he began to distance himself from the faith before becoming agnostic.[6] He later affirmed : "The philosophers are all in discord. I spent twelve years not denying and believing nothing, despairing of the truth, not even believing in God. No proof to me seemed evident".[7] This loss of the faith was accompanied by uneasiness : Charles found himself to be "all selfishness, all impiousness, all evil desire, I was as though distraught".[8][5]

On 11 April 1874, his cousin Marie married Olivier de Bondy.[6] A few months later, on 12 August 1874, Charles obtained his baccalauréat with the distinction "mention bien" (equivalent to magna cum laude).[6]

A dissipated youth

Charles was sent to the Sainte-Geneviève school (now located in Versailles), run by the Jesuites, at that time located in the Latin Quarter, Paris, in order to prepare the admission test for the Saint-Cyr Military Academy.[6] Charles was opposed to the strictness of the boarding school and decided to abandon all religious practice. He obtained his second baccalauréat in August 1875.[3] He led a dissipated lifestyle at that point in time and was expelled from the school for being "lazy and undisciplined"[9] in March 1876.[6]

He then returned to Nancy, where he studied tutoring whilst secretly perusing light readings.[6][3] During his readings with Gabriel Tourdes, he wanted to "completely enjoy that which is pleasant to the mind and body".[10][3] This reading Bulimia brought the two students to the works of Aristotle, Voltaire, Erasmus, Rabelais and Laurence Sterne.[5]

In June 1876, he applied for entrance to the Saint-Cyr Military Academy, and was accepted eighty-second out of four hundred and twelve.[3] He was one of the youngest in his class.[6] His record at Saint-Cyr was a mixed one and he graduated 333rd out of a class of 386.[11]

The death of Foucauld's grandfather and the receipt of a substantial inheritance, was followed by his entry into the French cavalry school at Saumur. Continuing to lead an extravagant life style, Foucauld was posted to the 4th Regiment of Chasseurs d'Afrique in Algeria. Bored with garrison service he travelled in Morocco (1883-84), the Sahara (1885), and Palestine (1888-89). While reverting to being a wealthy young socialite when in Paris, Foucauld became an increasingly serious student of the geography and culture of Algeria and Morocco. In 1885 the Societe de Geographie de Paris awarded him its gold medal in recognition of his exploration and research.[12]

Life as a clergyman, missionary and linguist

In 1890, de Foucauld joined the Cistercian Trappist order first in France and then at Akbès on the Syrian-Turkish border. He left in 1897 to follow an undefined religious vocation in Nazareth. He began to lead a solitary life of prayer near a convent of Poor Clares and it was suggested to him that he be ordained. In 1901, he was ordained in Viviers, France, and returned to the Sahara in French Algeria and lived a virtually eremitical life. He first settled in Béni Abbès, near the Moroccan border, building a small hermitage for "adoration and hospitality", which he soon referred to as the "Fraternity".

He moved to be with the Tuareg people, in Tamanghasset in southern Algeria. This region is the central part of the Sahara with the Ahaggar Mountains (the Hoggar) immediately to the west. Foucauld used the highest point in the region, the Assekrem, as a place of retreat. Living close to the Tuareg and sharing their life and hardships, he made a ten-year study of their language and cultural traditions. He learned the Tuareg language and worked on a dictionary and grammar. His dictionary manuscript was published posthumously in four volumes and has become known among Berberologists for its rich and apt descriptions. He formulated the idea of founding a new religious institute, under the name of the Little Brothers of Jesus.

Death

On 1 December 1916, de Foucauld was dragged from his fortress by a group of tribal raiders led by El Madani ag Soba, who was connected with the Senussi Bedouin. They intended to kidnap de Foucauld. But the tribesmen were disturbed by two Méharistes of the French Camel Corps. One startled bandit (15-year-old Sermi ag Thora) shot de Foucauld through the head, killing him instantly. The Méharistes were also shot dead.[13] The murder was witnessed by sacristan and servant Paul Embarek, an African Arab former slave liberated and instructed by de Foucauld.[14]

The French authorities continued for years searching for the bandits involved. In 1943 El Madani fled French forces in Libya to the remote South Fezzan. Sermi ag Thora was apprehended and executed at Djanet in 1944.[15]

De Foucauld was beatified by Cardinal José Saraiva Martins on 13 November 2005,[16][17][lower-alpha 1] and is listed as a martyr in the liturgy of the Catholic Church.

On May 27, 2020, Pope Francis issued a decree during a meeting the Congregation for the Causes of Saint prefect Cardinal Giovanni Angelo Becciu which approved a miracle clearing the way for Foucauld to become a saint.[19]

Legacy

Charles de Foucauld inspired and helped to organize a confraternity within France in support of his idea. This organisation, the Association of the Brothers and Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, consisted of 48 lay and ordained members at the time of his death. This group, notably Louis Massignon, the world-famous scholar of Islam, and René Bazin, author of a best-selling biography, La Vie de Charles de Foucauld Explorateur en Maroc, Ermite du Sahara (1921), kept his memory alive and inspired the family of lay and religious fraternities that include Jesus Caritas, the Little Brothers of Jesus and the Little Sisters of Jesus, among a total of ten religious congregations and nine associations of spiritual life. Though originally French in origin, these groups have expanded to include many cultures and their languages on all continents.

The 1936 French film The Call of Silence depicted his life.[20]

In 1950, the colonial Algerian government issued a postage stamp with his image. The French government did the same in 1959.

In 2013, partly inspired by the life of de Foucauld a community of consecrated brothers or monachelli (little monks) was established in Perth, Australia, called the Little Eucharistic Brothers of Divine Will.

Works

- Reconnaissance au Maroc, 1883–1884. 4 vols. Paris: Challamel, 1888.

- Dictionnaire Touareg–Français, Dialecte de l'Ahaggar. 4 vols. Paris: Imprimerie nationale de France, 1951–1952.

- Poésies Touarègues. Dialecte de l'Ahaggar. 2 vols. Paris: Leroux, 1925–1930.

Notes

- Pope Benedict XVI changed the procedure for beatification such that the pope no longer presides at beatification ceremonies, but instead the prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.[18]

References

- "Bienheureux Charles de Foucauld – Eglise Catholique en Ardèche". ardeche.catholique.fr. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Church promulgates new decrees for causes of saints", Vatican News, 27 May 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Vircondelet, Alain (1997). Charles de Foucauld, comme un agneau parmi des loups. Monaco: Le Rocher (éditions). ISBN 978-2-268-02661-9.

- Maxence, Jean-Luc (2004). L'Appel au désert, Charles de Foucauld, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Saint-Armand-Montrond: Presses de la Renaissance. ISBN 978-2-85616-838-7.

- Six, Jean-François (2008). Charles de Foucauld autrement. France: Desclée de Brouwer. ISBN 978-2-220-06011-8.

- Antier, Jean-Jacques (2005). Charles de Foucauld. Paris: Editions Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-01818-4.

- Letter from Charles de Foucauld to Henri de Castries on 14 August 1901, translated from French; orig. :" Les philosophes sont tous en désaccord. Je demeurai douze ans sans nier et sans rien croire, désespérant de la vérité, ne croyant même pas en Dieu. Aucune preuve ne me paraissait évidente "

- Letter from Charles de Foucauld to Marie de Castries on 17 April 1892, translated from French; orig. : " tout égoïsme, toute impiété, tout désir de mal, j'étais comme affolé "

- Translated from French, orig. : "paresse et indiscipline"

- Translated from French, orig. : " jouir d'une façon complète de ce qui est agréable au corps et à l'esprit "

- Fleming, Fergus (2003). The Sword and the Cross: Two Men and an Empire of Sand. New York: Grove Press. p. 23 ISBN 9780802117526.

- Fleming, Fergus (2003). The Sword and the Cross: Two Men and an Empire of Sand. New York: Grove Press. p. 58 ISBN 9780802117526.

- Fleming, Fergus (2003). The Sword and the Cross: Two Men and an Empire of Sand. New York: Grove Press. pp. 279–280. ISBN 9780802117526.

- Fremantle, Anne, Desert Calling: The Life of Charles de Foucauld, London: Hollis & Carter, 1950, pp324-6

- Fremantle, Anne, Desert Calling: The Life of Charles de Foucauld London: Hollis & Carter, 1950, p.328

- "Charles de Foucauld beatified in Rome". CathNews. 14 November 2005. Archived from the original on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- AsiaNews.it (12 November 2005). "Charles de Foucauld to be beatified tomorrow at St Peter's". GIAPPONE Tokyo, tolti i limiti a viaggi e intrattenimento. Covid-19 sotto controllo. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Martins, José Saraiva (29 September 2005). "New procedures in the Rite of Beatification". Vatican. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- https://cruxnow.com/vatican/2020/05/pope-clears-way-to-sainthood-for-three-advances-causes-of-others/

- Portuge, Catherine (1996). "Le Colonial Féminin: Women Directors Interrogate French Cinema". In Sherzer, Dina (ed.). Cinema, Colonialism, Postcolonialism: Perspectives from the French and Francophone Worlds. University of Texas Press. p. 97. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

Further reading

- Patrick Levaye (December 2016). Charles de Foucauld, Repères pour Aujourd'hui, Première Partie Editions (ISBN 978-2-36526-128-9)

- Casajus, Dominique (1997). "Charles de Foucauld et les Touaregs, Rencontre et Malentendu". Terrain 28: 29–42.

- Casajus, Dominique (2009). Charles de Foucauld: Moine et Savant. CNRS Éditions. ISBN 9782271066312.

- Chatelard, Antoine (2000). La Mort de Charles de Foucauld. Karthala Editions. ISBN 9782845861206.

- Fournier, Josette (2007). Charles de Foucauld: Amitiés Croisées. Éditions Cheminements. ISBN 9782844785695.

- Fremantle, Anne (1950). Desert Calling. The Story of Charles de Foucauld. London, Hollis & Carter.

- Galand, Lionel (1999). Lettres au Marabout. Messages Touaregs au Père de Foucauld. Paris, Belin, 1999.

- Wright, Cathy (2005). Charles de Foucauld – Journey of the Spirit. Pauline Books and Media. ISBN 9780819815767.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles de Foucauld. |

- Lay Fraternity, Lay Fraternity Page

- Facebook Group, Brother Charles' Facebook page

- Lay Fraternity in Canada, Canadian Lay Fraternity Page

- Association Famille Spirituelle Charles de Foucauld (Spiritual Family of Charles de Foucauld)

- Názáret, a Hungarian website about Charles de Foucauld and his spirituality

- "Charles de Foucauld" at Jesus Caritas

- "Books by or about Charles de Foucauld" at Jesus Caritas

- Charles de Foucauld at Find a Grave

- Newspaper clippings about Charles de Foucauld in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- An "Insight" episode based on Charles de Foucauld, portrayed by Efrem Zimbalist, Jr.