Timekeeping on Mars

Various schemes have been used or proposed for timekeeping on the planet Mars independently of Earth time and calendars.

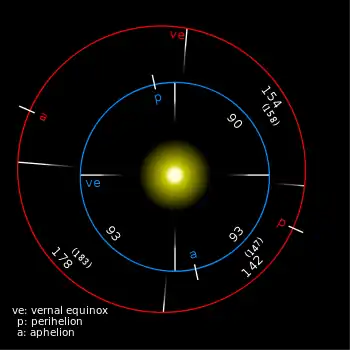

Mars has an axial tilt and a rotation period similar to those of Earth. Thus, it experiences seasons of spring, summer, autumn and winter much like Earth. Coincidentally, the duration of a Martian day is within a few percent of that of an Earth day, which has led to the use of analogous time units. A Mars year is almost twice as long as Earth's, and its orbital eccentricity is considerably larger, which means that the lengths of various Martian seasons differ considerably, and sundial time can diverge from clock time more than on Earth.

Sols

The average length of a Martian sidereal day is 24 h 37 m 22.663 s (88,642.663 seconds based on SI units), and the length of its solar day is 24 h 39 m 35.244 s (88,775.244 seconds).[1] The corresponding values for Earth are currently 23 h 56 m 4.0916 s and 24 h 00 m 00.002 s, respectively. This yields a conversion factor of 1.02749125170 Earth days/sol. Thus Mars's solar day is only about 2.7% longer than Earth's.

The term "sol" is used by planetary scientists to refer to the duration of a solar day on Mars. The term was adopted during the Viking project in order to avoid confusion with an Earth day.[2] By inference, Mars' "solar hour" is 1/24 of a sol, and a solar minute 1/60 of a solar hour.[3]

Time of day

A convention used by spacecraft lander projects to date has been to enumerate local solar time using a 24-hour "Mars clock" on which the hours, minutes and seconds are 2.7% longer than their standard (Earth) durations. For the Mars Pathfinder, Mars Exploration Rover (MER), Phoenix, and Mars Science Laboratory missions, the operations teams have worked on "Mars time", with a work schedule synchronized to the local time at the landing site on Mars, rather than the Earth day. This results in the crew's schedule sliding approximately 40 minutes later in Earth time each day. Wristwatches calibrated in Martian time, rather than Earth time, were used by many of the MER team members.[4][5]

Local solar time has a significant impact on planning the daily activities of Mars landers. Daylight is needed for the solar panels of landed spacecraft. Its temperature rises and falls rapidly at sunrise and sunset because Mars does not have the Earth's thick atmosphere and oceans that soften such fluctuations. Consensus has recently been gained in the scientific community studying Mars to similarly define Martian local hours as 1/24th of a Mars day.[6]

As on Earth, on Mars there is also an equation of time that represents the difference between sundial time and uniform (clock) time. The equation of time is illustrated by an analemma. Because of orbital eccentricity, the length of the solar day is not quite constant. Because its orbital eccentricity is greater than that of Earth, the length of day varies from the average by a greater amount than that of Earth, and hence its equation of time shows greater variation than that of Earth: on Mars, the Sun can run 50 minutes slower or 40 minutes faster than a Martian clock (on Earth, the corresponding figures are 14m 22s slower and 16m 23s faster).

Mars has a prime meridian, defined as passing through the small crater Airy-0. However, Mars does not have time zones defined at regular intervals from the prime meridian, as on Earth. Each lander so far has used an approximation of local solar time as its frame of reference, as cities did on Earth before the introduction of standard time in the 19th century. (The two Mars Exploration Rovers happen to be approximately 12 hours and one minute apart.)

The most widely used standard for specifying locations on Mars uses "planetocentric coordinates", which measure longitude 0°–360° East and latitude angles from the center of Mars. An alternative used in some scientific literature may use planetographic coordinates, which measure longitudes as 0°–360° West and determined latitudes as mapped onto the surface.[7]

Coordinated Mars Time

Coordinated Mars Time (MTC) or Martian Coordinated Time is a proposed Mars analog to Universal Time (UT1) on Earth. It is defined as the mean solar time at Mars's prime meridian. The prime meridian was first proposed by German astronomers Wilhelm Beer and Johann Heinrich Mädler in 1830 as marked by the fork in the albedo feature later named Sinus Meridiani by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli. This convention was readily adopted by the astronomical community, the result being that Mars had a universally accepted prime meridian half a century before the International Meridian Conference of 1884 established one for Earth. The definition of the Martian prime meridian has since been refined on the basis of spacecraft imagery as the center of the crater Airy-0 in Terra Meridiani. The name "MTC" is intended to parallel the Terran Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), but this is somewhat misleading: what distinguishes UTC from other forms of UT is its leap seconds, but MTC does not use any such scheme. MTC is more closely analogous to UT1.

Use of the term "Martian Coordinated Time" as a planetary standard time first appeared in a journal article in 2000.[8] The abbreviation "MTC" was used in some versions of the related Mars24[9] sunclock coded by the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. That application has also denoted the standard time as "Airy Mean Time" (AMT), in analogy of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). In an astronomical context, "GMT" is a deprecated name for Universal Time, or sometimes more specifically for UT1.

Neither AMT or MTC has yet been employed in mission timekeeping. This is partially attributable to uncertainty regarding the position of Airy-0 (relative to other longitudes), which meant that AMT could not be realized as accurately as local time at points being studied. At the start of the Mars Exploration Rover missions, the positional uncertainty of Airy-0 corresponded to roughly a 20-second uncertainty in realizing AMT. In order to refine the location of the prime meridian, it has been proposed that it be based on a specification that the Viking Lander 1 is located at 47.95137°W.[10] [11]

Lander mission clocks

When a spacecraft lander begins operations on Mars, the passing Martian days (sols) are tracked using a simple numerical count. The two Viking missions, Mars Phoenix, the Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity, and InSight missions all count the sol on which the lander touched down as "Sol 0". Mars Pathfinder and the two Mars Exploration Rovers instead defined touchdown as "Sol 1".[12]

Each successful lander mission so far has used its own "time zone", corresponding to some defined version of local solar time at the landing site location. Of the seven successful Mars landers to date, six employed offsets from local mean solar time (LMST) for the lander site while the seventh (Mars Pathfinder) used local true solar time (LTST).[8][1]

Viking Landers

The "local lander time" for the two Viking mission landers were offsets from LMST at the respective lander sites. In both cases, the initial clock midnight was set to match local true midnight immediately preceding touchdown.

Pathfinder

Mars Pathfinder used the local apparent solar time at its location of landing. Its time zone was AAT-02:13:01, where "AAT" is Airy Apparent Time, meaning apparent solar time at Airy-0.

Spirit and Opportunity

The two Mars Exploration Rovers did not use mission clocks matched to the LMST of their landing points. For mission planning purposes, they instead defined a time scale that would approximately match the clock to the apparent solar time about halfway through the nominal 90-sol primary mission. This was referred to in mission planning as "Hybrid Local Solar Time" (HLST) or as the "MER Continuous Time Algorithm". These time scales were uniform in the sense of mean solar time (i.e., they approximate the mean time of some longitude) and were not adjusted as the rovers traveled. (The rovers traveled distances that could make a few seconds difference to local solar time.) The HLST of Spirit is AMT+11:00:04 whereas the LMST at its landing site is AMT+11:41:55. The HLST of Opportunity is AMT-01:01:06 whereas the LMST at its landing site is AMT-00:22:06. Neither rover was likely to ever reach the longitude at which its mission time scale matches local mean time. For science purposes, Local True Solar Time is used.

Phoenix

The Mars Phoenix project specified a mission clock that matched Local Mean Solar Time at the planned landing longitude of -126.65°E. This corresponds to a mission clock of AMT-08:26:36. The actual landing site was about 0.7° east of that.

Curiosity

The MSL Curiosity rover project specified a mission clock that matched Local Mean Solar Time at its originally planned landing longitude of 137.42°E (the actual landing site was about 0.2° east of that). This corresponds to a mission clock of AMT+09:09:40.8.

InSight

The InSight lander project specified a mission clock that matched Local Mean Solar Time at its planned landing site of 135.970°E. This corresponds to a mission clock of AMT+09:03:53. The actual landing site was at 135.623447°E.

Perseverance

The Perseverance rover project has specified a mission clock that matches Local Mean Solar Time at a planned landing longitude of 77.43°E. This corresponds to a mission clock of AMT+05:09:43.

Mars Sol date

On Earth, astronomers often use Julian dates—a simple sequential count of days—for timekeeping purposes. An analogous system for Mars has been proposed "[f]or historical utility with respect to the Earth-based atmospheric, visual mapping, and polar-cap observations of Mars…, a sequential count of sol-numbers"[upper-alpha 1]. This Mars Sol Date (MSD) starts "prior to the 1877 perihelic opposition."[8] Thus, the MSD is a running count of sols since 29 December 1873 (coincidentally the birth date of astronomer Carl Otto Lampland). Numerically, the Mars Sol Date is defined as MSD = (Julian Date using International Atomic Time - 2451549.5 + k)/1.02749125 + 44796.0, where k is a small correction of approximately 0.00014 d (or 12 s) due to uncertainty in the exact geographical position of the prime meridian at Airy-0 crater.

Years

Definition of year and seasons

The length of time for Mars to complete one orbit around the Sun is its sidereal year, and is about 686.98 Earth solar days, or 668.5991 sols. Because of the eccentricity of Mars' orbit, the seasons are not of equal length. Assuming that seasons run from equinox to solstice or vice versa, the season Ls 0 to Ls 90 (northern-hemisphere spring / southern-hemisphere autumn) is the longest season lasting 194 Martian sols, and Ls 180 to Ls 270 (northern hemisphere autumn / southern-hemisphere spring) is the shortest season, lasting only 142 Martian sols.[13]

As on Earth, the sidereal year is not the quantity that is needed for calendar purposes. Rather, the tropical year would be likely to be used because it gives the best match to the progression of the seasons. It is slightly shorter than the sidereal year due to the precession of Mars' rotational axis. The precession cycle is 93,000 Martian years (175,000 Earth years), much longer than on Earth. Its length in tropical years can be computed by dividing the difference between the sidereal year and tropical year by the length of the tropical year.

Tropical year length depends on the starting point of measurement, due to the effects of Kepler's second law of planetary motion. It can be measured in relation to an equinox or solstice, or can be the mean of various possible years including the March (northward) equinox year, June (northern) solstice year, the September (southward) equinox year, the December (southern) solstice year, and other such years. The Gregorian calendar uses the March equinox year.

On Earth, the variation in the lengths of the tropical years is small, but on Mars it is much larger. The northward equinox year is 668.5907 sols, the northern solstice year is 668.5880 sols, the southward equinox year is 668.5940 sols, and the southern solstice year is 668.5958 sols. Averaging over an entire orbital period gives a tropical year of 668.5921 sols. (Since, like Earth, the northern and southern hemispheres of Mars have opposite seasons, equinoxes and solstices must be labelled by hemisphere to remove ambiguity.)

Seasons begin at 90 degree intervals of solar longitude (Ls) at equinoxes and solstices.[6]

| solar longitude (Lsº) | event | months | northern hemisphere | southern hemisphere | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| event | season | event | seasons | |||

| 0 | northward equinox | 1, 2, 3 | vernal equinox | spring | autumnal equinox | autumn |

| 90 | northern solstice | 4, 5, 6 | summer solstice | summer | winter solstice | winter |

| 180 | southward equinox | 7, 8, 9 | autumnal equinox | autumn | vernal equinox | spring |

| 270 | southern solstice | 10, 11, 12 | winter solstice | winter | summer solstice | summer |

Year numbering

For purposes of enumerating Mars years and facilitating data comparisons, a system increasingly used in the scientific literature, particularly studies of Martian climate, enumerates years relative to the northern spring equinox (Ls 0) that occurred on April 11, 1955, labeling it a Mars Year 1 (MY1). The system was first described in a paper focused on seasonal temperature variation by R. Todd Clancy of the Space Science Institute.[14] Although Clancy and co-authors described the choice as "arbitrary", the great dust storm of 1956 falls in MY1. This system has been extended by defining Mars Year 0 (MY0) as beginning May 24, 1953, and so allowing for negative year numbers.[6]

| Dates of Mars Seasons for Mars Years[15] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MY | Spring equinox (Ls = 0°) | Summer solstice (Ls = 90°) | Autumnal equinox (Ls = 180°) | Winter solstice (Ls = 270°) | Events Earth Date [Mars Year/Lsº] |

| 0 | 1953-05-24 | ||||

| 1 | 1955-04-11 | 1955-10-27 | 1956-04-27 | 1956-09-21 | |

| 2 | 1957-02-26 | 1957-09-13 | 1958-03-15 | 1958-08-09 | |

| 3 | 1959-01-14 | 1959-08-01 | 1960-01-31 | 1960-06-26 | |

| 4 | 1960-12-01 | 1961-06-18 | 1961-12-18 | 1962-05-14 | |

| 5 | 1962-10-19 | 1963-05-05 | 1963-11-05 | 1964-03-31 | |

| 6 | 1964-09-05 | 1965-03-22 | 1965-09-22 | 1966-02-15 | 1964-07-14 [6/143º] Mariner 4 flyby |

| 7 | 1966-07-24 | 1967-02-07 | 1967-08-10 | 1968-01-03 | |

| 8 | 1968-06-10 | 1968-12-25 | 1969-06-27 | 1969-11-20 | 1969-07-31 [8/200º] Mariner 6 and Mariner 7 flybys |

| 9 | 1970-04-28 | 1970-11-12 | 1971-05-15 | 1971-10-08 | 1971-11-14 [9/284º] Mariner 9 enters orbit 1971-11-27 Mars 2 enters orbit 1971-12-02 Mars 3 enters orbit |

| 10 | 1972-03-15 | 1972-09-29 | 1973-04-01 | 1973-08-25 | |

| 11 | 1974-01-31 | 1974-08-17 | 1975-02-17 | 1975-07-13 | 1974-02 [11/0º] Mars 4 and Mars 5 enter orbit |

| 12 | 1975-12-19 | 1976-07-04 | 1977-01-04 | 1977-05-30 | 1976-07 [12/88º] Viking 1 Orbiter & Lander arrive 1976-09 [12/116º] Viking 2 Orbiter & Lander arrive |

| 13 | 1977-11-05 | 1978-05-22 | 1978-11-22 | 1979-04-17 | |

| 14 | 1979-09-23 | 1980-04-08 | 1980-10-09 | 1981-03-04 | |

| 15 | 1981-08-10 | 1982-02-24 | 1982-08-27 | 1983-01-20 | |

| 16 | 1983-06-28 | 1984-01-12 | 1984-07-14 | 1984-12-07 | |

| 17 | 1985-05-15 | 1985-11-29 | 1986-06-01 | 1986-10-25 | |

| 18 | 1987-04-01 | 1987-10-17 | 1988-04-18 | 1988-09-11 | 1989-01-29 [19/350º] Phobos 2 enters orbit |

| 19 | 1989-02-16 | 1989-09-03 | 1990-03-06 | 1990-07-30 | |

| 20 | 1991-01-04 | 1991-07-22 | 1992-01-22 | 1992-06-16 | |

| 21 | 1992-11-21 | 1993-06-08 | 1993-12-08 | 1994-05-04 | |

| 22 | 1994-10-09 | 1995-04-26 | 1995-10-26 | 1996-03-21 | |

| 23 | 1996-08-26 | 1997-03-13 | 1997-09-12 | 1998-02-06 | 1997-07-04 [23/142º] Mars Pathfinder arrives 1997-09 [23/173º] Mars Global Surveyor enters orbit |

| 24 | 1998-07-14 | 1999-01-29 | 1999-07-31 | 1999-12-25 | |

| 25 | 2000-05-31 | 2000-12-16 | 2001-06-17 | 2001-11-11 | 2001-10-24 [25/258º] Mars Odyssey enters orbit |

| 26 | 2002-04-18 | 2002-11-03 | 2003-05-05 | 2003-09-29 | 2003-12-14 [26/315º] Nozomi flies past Mars 2004-01 [26/325º] Mars Express, Spirit Rover, and Opportunity Rover arrive |

| 27 | 2004-03-05 | 2004-09-20 | 2005-03-22 | 2005-08-16 | |

| 28 | 2006-01-21 | 2006-08-08 | 2007-02-07 | 2007-07-04 | 2006-03-10 [28/22º] Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter arrives |

| 29 | 2007-12-09 | 2008-06-25 | 2008-12-25 | 2009-05-21 | 2008-05-25 [29/76º] Phoenix lander arrives |

| 30 | 2009-10-26 | 2010-05-13 | 2010-11-12 | 2011-04-08 | |

| 31 | 2011-09-13 | 2012-03-30 | 2012-09-29 | 2013-02-23 | 2012-08-06 [31/150º] Curiosity Rover arrives |

| 32 | 2013-07-31 | 2014-02-15 | 2014-08-17 | 2015-01-11 | 2014-09-22 [32/200º] MAVEN arrives 2014-09-24 [32/202] Mars Orbiter Mission arrives |

| 33 | 2015-06-18 | 2016-01-03 | 2016-07-04 | 2016-11-28 | |

| 34 | 2017-05-05 | 2017-11-20 | 2018-05-22 | 2018-10-16 | |

| 35 | 2019-03-23 | 2019-10-08 | 2020-04-08 | 2020-09-02 | |

| 36 | 2021-02-07 | 2021-08-25 | 2022-02-24 | 2022-07-21 | |

| 37 | 2022-12-26 | 2023-07-12 | 2024-01-12 | 2024-06-07 | |

| 38 | 2024-11-12 | 2025-05-29 | 2025-11-29 | 2026-04-25 | |

| 39 | 2026-09-30 | 2027-04-16 | 2027-10-17 | 2028-03-12 | |

| 40 | 2028-08-17 | 2029-03-03 | 2029-09-03 | 2030-01-28 | |

Martian calendars in science

Long before mission control teams on Earth began scheduling work shifts according to the Martian sol while operating spacecraft on the surface of Mars, it was recognized that humans probably could adapt to this slightly longer diurnal period. This suggested that a calendar based on the sol and the Martian year might be a useful timekeeping system for astronomers in the short term and for explorers in the future. For most day-to-day activities on Earth, people do not use Julian days, as astronomers do, but the Gregorian calendar, which despite its various complications is quite useful. It allows for easy determination of whether one date is an anniversary of another, whether a date is in winter or spring, and what is the number of years between two dates. This is much less practical with Julian days count. For similar reasons, if it is ever necessary to schedule and co-ordinate activities on a large scale across the surface of Mars it would be necessary to agree on a calendar.

American astronomer Percival Lowell expressed the time of year on Mars in terms of Mars dates that were analogous to Gregorian dates, with 20 March, 21 June, 22 September, and 21 December marking the southward equinox, southern solstice, northward equinox, and northern solstice, respectively; Lowell's focus was on the southern hemisphere of Mars because it is the hemisphere that is more easily observed from Earth during favorable oppositions. Lowell's system was not a true calendar, since a Mars date could span nearly two entire sols; rather it was a convenient device for expressing the time of year in the southern hemisphere in lieu of heliocentric longitude, which would have been less comprehensible to a general readership.[16]

Italian astronomer Mentore Maggini's 1939 book describes a calendar developed years earlier by American astronomers Andrew Ellicott Douglass and William H. Pickering, in which the first nine months contain 56 sols and the last three months contain 55 sols. Their calendar year begins with the northward equinox on 1 March, thus imitating the original Roman calendar. Other dates of astronomical significance are: northern solstice, 27 June; southward equinox, 36 September; southern solstice, 12 December; perihelion, 31 November; and aphelion, 31 May. Pickering's inclusion of Mars dates in a 1916 report of his observations may have been the first use of a Martian calendar in an astronomical publication.[17] Maggini states: "These dates of the Martian calendar are frequently used by observatories...."[18] Despite his claim, this system eventually fell into disuse, and in its place new systems were proposed periodically which likewise did not gain sufficient acceptance to take permanent hold.

In 1936, when the calendar reform movement was at its height, American astronomer Robert G. Aitken published an article outlining a Martian calendar. In each quarter there are three months of 42 sols and a fourth month of 41 sols. The pattern of seven-day weeks repeats over a two-year cycle, i.e., the calendar year always begins on a Sunday in odd-numbered years, thus effecting a perpetual calendar for Mars.[19]

Whereas previous proposals for a Martian calendar had not included an epoch, American astronomer I. M. Levitt developed a more complete system in 1954. In fact, Ralph Mentzer, an acquaintance of Levitt's who was a watchmaker for the Hamilton Watch Company, built several clocks designed by Levitt to keep time on both Earth and Mars. They could also be set to display the date on both planets according to Levitt's calendar and epoch (the Julian day epoch of 4713 BCE).[20][21]

Charles F. Capen included references to Mars dates in a 1966 Jet Propulsion Laboratory technical report associated with the Mariner 4 flyby of Mars. This system stretches the Gregorian calendar to fit the longer Martian year, much as Lowell had done in 1895, the difference being that 20 March, 21 June, 22 September, and 21 December marks the northward equinox, northern solstice, southward equinox, southern solstice, respectively.[22] Similarly, Conway B. Leovy et al. also expressed time in terms of Mars dates in a 1973 paper describing results from the Mariner 9 Mars orbiter. [23]

British astronomer Sir Patrick Moore described a Martian calendar of his own design in 1977. His idea was to divide up a Martian year into 18 months. Months 6, 12 and 18, have 38 sols, while the rest of the months contain 37 sols.[24]

American aerospace engineer and political scientist Thomas Gangale first published regarding the Darian calendar in 1986, with additional details published in 1998 and 2006. It has 24 months to accommodate the longer Martian year while keeping the notion of a "month" that is reasonably similar to the length of an Earth month. On Mars, a "month" would have no relation to the orbital period of any moon of Mars, since Phobos and Deimos orbit in about 7 hours and 30 hours respectively. However, Earth and Moon would generally be visible to the naked eye when they were above the horizon at night, and the time it takes for the Moon to move from maximum separation in one direction to the other and back as seen from Mars is close to a Lunar month.[25][26][27]

Czech astronomer Josef Šurán offered a Martian calendar design in 1997, in which a common year has 672 Martian days distributed into 24 months of 28 days (or 4 weeks of 7 days each); in skip years an entire week at the end of the twelfth month is omitted.[28]

Martian time in fiction

The first known reference to time on Mars appears in Percy Greg's novel Across the Zodiac (1880). The primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary divisions of the sol are based on the number 12. Sols are numbered 0 through the end of the year, with no additional structure to the calendar. The epoch is "the union of all races and nations in a single State, a union which was formally established 13,218 years ago".[29]

20th century

Edgar Rice Burroughs described, in The Gods of Mars (1913), the divisions of the sol into zodes, xats, and tals.[30] Although possibly the first to make the mistake of describing the Martian year as lasting 687 Martian days, he was far from the last.[31]

In the Robert A. Heinlein novel Red Planet (1949), humans living on Mars use a 24-month calendar, alternating between familiar Earth months and newly created months such as Ceres and Zeus. For example, Ceres comes after March and before April, while Zeus comes after October and before November.[32]

The Arthur C. Clarke novel The Sands of Mars (1951) mentions in passing that "Monday followed Sunday in the usual way" and "the months also had the same names, but were fifty to sixty days in length".[33]

In H. Beam Piper's short story "Omnilingual" (1957), the Martian calendar and the periodic table are the keys to archaeologists' deciphering of the records left by the long dead Martian civilization.[34]

Kurt Vonnegut's novel The Sirens of Titan (1959) describes a Martian calendar divided into twenty-one months: "twelve with thirty sols, and nine with thirty-one sols", for a total of only 639 sols.[35]

D. G. Compton states in his novel Farewell, Earth's Bliss (1966), during the prison ship's journey to Mars: "Nobody on board had any real idea how the people in the settlement would have organised their six-hundred-and-eighty-seven-day year."[36]

In Ian McDonald's Desolation Road (1988), set on a terraformed Mars (referred to by the book's characters as "Ares"), characters follow an implied 24-month calendar whose months are portmanteaus of Gregorian months, such as "Julaugust", "Augtember", and "Novodecember".

In both Philip K. Dick's novel Martian Time-Slip and Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars Trilogy (1992–1996), clocks retain Earth-standard seconds, minutes, and hours, but freeze at midnight for 39.5 minutes. As the fictional colonization of Mars progresses, this "timeslip" becomes a sort of witching hour, a time when inhibitions can be shed, and the emerging identity of Mars as a separate entity from Earth is celebrated. (It is not said explicitly whether this occurs simultaneously all over Mars, or at local midnight in each longitude.) Also in the Mars Trilogy, the calendar year is divided into twenty-four months. The names of the months are the same as the Gregorian calendar, except for a "1" or "2" in front to indicate the first or second occurrence of that month (for example, 1 January, 2 January, 1 February, 2 February).

21st century

In the manga and anime series Aria (2001–2002), by Kozue Amano, set on a terraformed Mars, the calendar year is also divided into twenty-four months. Following the modern Japanese calendar, the months are not named but numbered sequentially, running from 1st Month to 24th Month.[37]

The Darian calendar is mentioned in a couple of works of fiction set on Mars:

- Star Trek: Department of Temporal Investigations: Watching the Clock by Christopher L. Bennett, Pocket Books/Star Trek (April 26, 2011)

- The Quantum Thief by Hannu Rajaniemi, Tor Books; Reprint edition (May 10, 2011)

In Andy Weir's novel The Martian (2011) and its 2015 feature film adaptation, sols are counted and referenced frequently with onscreen title cards, in order to emphasize the amount of time the main character spends on Mars.[38]

Formulas to compute MSD and MTC

The Mars Sol Date (MSD) can be computed from the Julian date referred to Terrestrial Time (TT), as[39]

- MSD = (JDTT − 2405522.0028779) / 1.0274912517

Terrestrial time, however, is not as easily available as Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). TT can be computed from UTC by first adding the difference TAI−UTC, which is a positive integer number of seconds occasionally updated by the introduction of leap seconds (see current number of leap seconds), then adding the constant difference TT−TAI = 32.184 s. This leads to the following formula giving MSD from the UTC-referred Julian date:

- MSD = (JDUTC + (TAI−UTC)/86400 − 2405522.0025054) / 1.0274912517

where the difference TAI−UTC is in seconds. JDUTC can in turn be computed from any epoch-based time stamp, by adding the Julian date of the epoch to the time stamp in days. For example, if t is a Unix timestamp in seconds, then

- JDUTC = t / 86400 + 2440587.5

It follows, by a simple substitution:

- MSD = (t + (TAI−UTC)) / 88775.244147 + 34127.2954262

MTC is the fractional part of MSD, in hours, minutes and seconds:[1]

- MTC = (MSD mod 1) × 24 h

For example, at the time this page was last generated (4 Feb 2021, 03:36:11 UTC):

- JDTT = 2459249.65093

- MSD = 52290.12701

- MTC = 03:02:53

Notes

- Sol (borrowed from the Latin word for sun) is a solar day on Mars

References

- Allison, Michael (5 August 2008). "Technical Notes on Mars Solar Time". NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- Snyder, Conway W. (1979). "The extended mission of Viking". Journal of Geophysical Research. 84 (B14): 7917–7933. doi:10.1029/JB084iB14p07917.

- Allison, Michael (1997). "Accurate analytic representations of solar time and seasons on Mars with applications to the Pathfinder/Surveyor missions". Geophysical Research Letters. 24 (16): 1967–1970. doi:10.1029/97GL01950.

- "Watchmaker With Time to Lose". JPL Mars Exploration Rovers. 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Redd, Nola Taylor (18 March 2013). "After Finding Mars Was Habitable, Curiosity Keeps Roving". space.com. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Picqueux, S.; Byrne, S.; Kieffer, H.H.; Titus, T.N.; Hansen, C.J. (2015). "Enumeration of Mars years and seasons since the beginning of telescopic observations". Icarus. 251: 332–338. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.12.014.

- "Mars Express – Where is zero degrees longitude on Mars?". European Space Agency. 19 August 2004. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- Allison, Michael; McEwen, Megan (2000). "A post-Pathfinder evaluation of areocentric solar coordinates with improved timing recipes for Mars seasonal/diurnal climate studies". Planetary and Space Science. 48 (2–3): 215–235. Bibcode:2000P&SS...48..215A. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(99)00092-6. hdl:2060/20000097895.

- "Mars24 Sunclock – Time on Mars". NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- Kuchynka, P.; Folkner, W.M.; Konopliv, A.S.; Parker, T.J.; Park, R.S.; Le Maistre, S.; Dehant, V. (2014). "New constraints on Mars rotation determined from radiometric tracking of the Opportunity Mars Exploration Rover". Icarus. 229: 340–347. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.11.015.

- "New Coordinate Systems for Solar System Bodies". International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- "Phoenix Mars Mission - Mission - Mission Phases - On Mars". Phoenix.lpl.arizona.edu. 29 February 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- J. Appelbaum and G. A. Landis, Solar Radiation on Mars – Update 1991, NASA Technical Memorandum TM-105216, September 1991 (also published in Solar Energy, Vol. 50, No. 1 (1993)).

- Clancy, R. T.; Sandor, B. J.; Wolff, M. J.; Christensen, P. R.; Smith, M. D.; Pearl, J. C.; Conrath, B. J.; Wilson, R. J. (2000). "An intercomparison of ground-based millimeter, MGS TES, and Viking atmospheric temperature measurements: Seasonal and interannual variability of temperatures and dust loading in the global Mars atmosphere". Journal of Geophysical Research. 105 (E4): 9553–9571. Bibcode:2000JGR...105.9553C. doi:10.1029/1999JE001089.).

- Mars' Calendar

- Lowell, Percival. (1895-01-01). Mars. Houghton, Mifflin.

- Pickering, William H. (1916-01-01). "Report on Mars, No. 17." Popular Astronomy, Vol. 24, p.639.

- Maggini, Mentore. (1939-01-01). Il pianeta Marte. Scuola Tip. Figli Della Provvidenza.

- Aitken, Robert G. (1936-12-01). "Time Measures on Mars." Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets, No. 95.

- Levitt, I. M. (1954-05-01). "Mars Clock and Calendar." Sky and Telescope, May, 1954, pp. 216–217.

- Levitt, I. M. (1956-01-01). A Space Traveller's Guide to Mars. Henry Holt.

- Capen, Charles F. (1966-01-01). "The Mars 1964–1965 Apparition." Technical Report 32-990. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology..

- Leovy, C. B.; Briggs, G.A.; Smith, B.A. (1973). "Mars atmosphere during the Mariner 9 extended mission: Television results". Journal of Geophysical Research. 78 (20): 4252–4266. doi:10.1029/JB078i020p04252.

- Moore, Patrick. (1977-01-01). Guide to Mars. Lutterworth Press.

- Gangale, Thomas. (1986-06-01). "Martian Standard Time". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. Vol. 39, No. 6, p. 282–288.

- Gangale, Thomas. (1998-08-01). "The Darian Calendar". Mars Society. MAR 98-095. Proceedings of the Founding Convention of the Mars Society. Volume III. Ed. Robert M. Zubrin, Maggie Zubrin. San Diego, California. Univelt, Incorporated. 13-Aug-1998.

- Gangale, Thomas. (2006-07-01). "The Architecture of Time, Part 2: The Darian System for Mars." Society of Automotive Engineers. SAE 2006-01-2249.

- Šurán, Josef (1997). "A Calendar for Mars". Planetary and Space Science. 45 (6): 705–708. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(97)00033-0.

- Greg, Percy. (1880-01-01). Across the Zodiac: The Story of a Wrecked Record. Trübner.

- Burroughs, Edgar Rice. (1913-01-01). The Gods of Mars. All-Story. January–May.

- Burroughs, Edgar Rice. (1913-12-01). The Warlord of Mars. All-Story Magazine, December, 1913 – March, 1914.

- "Heinlein Concordance "Red Planet"". Heinlein Society. 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Clarke, Arthur C. (1951-01-01). The Sands of Mars. Sidgwick & Jackson.

- Piper, H. Beam. (1957-02-01). "Omnilingual." Astounding Science Fiction, February.

- Vonnegut, Kurt. (1959-01-01). The Sirens of Titan. Delacorte.

- Compton. D. G. (1966-01-01). Farewell, Earth's Bliss. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Amano, Kozue (February 2008). "Navigation 06: My First Customer". Aqua volume 2. Tokyopop. p. 7. ISBN 978-1427803139.

- Weir, Andy (January 5, 2015). "FaceBook – Andy Weir's Page – Timeline Photos (comment)". Facebook. Retrieved November 16, 2015. "Ares 3 launched on July 7, 2035. They landed on Mars (Sol 1) on November 7, 2035. The story begins on Sol 6, which is November 12, 2035." – Andy Weir

- This is a trivial simplification of the formula (JDTT − 2451549.5) / 1.0274912517 + 44796.0 − 0.0009626 given in Mars24 Algorithm and Worked Examples.