Greenwich Mean Time

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the mean solar time at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, reckoned from midnight. At different times in the past, it has been calculated in different ways, including being calculated from noon;[1] as a consequence, it cannot be used to specify a precise time unless a context is given.

| Greenwich Mean Time | |

|---|---|

| time zone | |

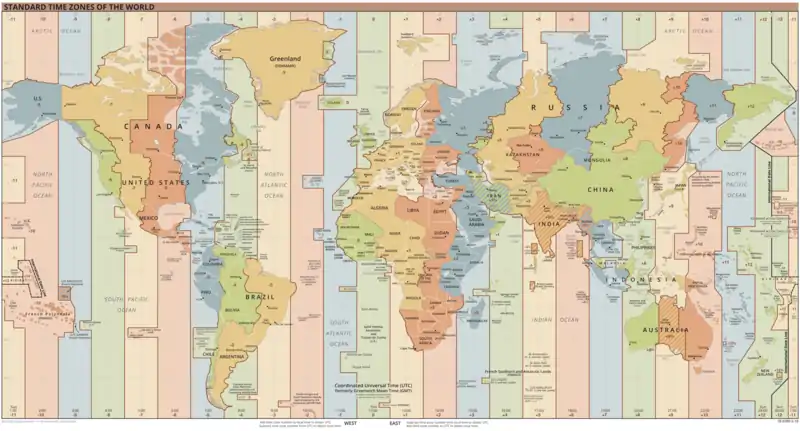

World map with the time zone highlighted | |

| UTC offset | |

| GMT | UTC±00:00 |

| Current time | |

| 08:24, 9 February 2021 GMT [refresh] | |

| -01:00 | Cape Verde Time[a] |

| ±00:00 | Greenwich Mean Time |

| +01:00 | West Africa Time |

| +02:00 | |

| +03:00 | East Africa Time |

| +04:00 |

b Mauritius and the Seychelles are to the east and north-east of Madagascar respectively.

English speakers often use GMT as a synonym for Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).[2] For navigation, it is considered equivalent to UT1 (the modern form of mean solar time at 0° longitude); but this meaning can differ from UTC by up to 0.9 s. The term GMT should not thus be used for certain technical purposes requiring precision.[3]

Because of Earth's uneven angular velocity in its elliptical orbit and its axial tilt, noon (12:00:00) GMT is rarely the exact moment the Sun crosses the Greenwich meridian and reaches its highest point in the sky there. This event may occur up to 16 minutes before or after noon GMT, a discrepancy calculated by the equation of time. Noon GMT is the annual average (i.e. "mean") moment of this event, which accounts for the word "mean" in "Greenwich Mean Time".

Originally, astronomers considered a GMT day to start at noon, while for almost everyone else it started at midnight. To avoid confusion, the name Universal Time was introduced to denote GMT as counted from midnight.[4] Astronomers preferred the old convention to simplify their observational data, so that each night was logged under a single calendar date. Today, Universal Time usually refers to UTC or UT1.[5]

The term "GMT" is especially used by bodies connected with the United Kingdom, such as the BBC World Service, the Royal Navy, and the Met Office; and others particularly in Arab countries, such as the Middle East Broadcasting Centre and OSN. It is a term commonly used in the United Kingdom and countries of the Commonwealth, including Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Malaysia; and in many other countries of the Eastern Hemisphere.

History

As the United Kingdom developed into an advanced maritime nation, British mariners kept at least one chronometer on GMT to calculate their longitude from the Greenwich meridian, which was considered to have longitude zero degrees, by a convention adopted in the International Meridian Conference of 1884. Synchronisation of the chronometer on GMT did not affect shipboard time, which was still solar time. But this practice, combined with mariners from other nations drawing from Nevil Maskelyne's method of lunar distances based on observations at Greenwich, led to GMT being used worldwide as a standard time independent of location. Most time zones were based upon GMT, as an offset of a number of hours (and possibly half or quarter hours) "ahead of GMT" or "behind GMT".

Greenwich Mean Time was adopted across the island of Great Britain by the Railway Clearing House in 1847 and by almost all railway companies by the following year, from which the term "railway time" is derived. It was gradually adopted for other purposes, but a legal case in 1858 held "local mean time" to be the official time.[6] On 14 May 1880, a letter signed by "Clerk to Justices" appeared in The Times, stating that "Greenwich time is now kept almost throughout England, but it appears that Greenwich time is not legal time. For example, our polling booths were opened, say, at 8 13 and closed at 4 13 p.m."[7][8] This was changed later in 1880, when Greenwich Mean Time was legally adopted throughout the island of Great Britain. GMT was adopted in the Isle of Man in 1883, in Jersey in 1898 and in Guernsey in 1913. Ireland adopted GMT in 1916, supplanting Dublin Mean Time.[9] Hourly time signals from Greenwich Observatory were first broadcast on 5 February 1924, rendering the time ball at the observatory redundant.

The daily rotation of the Earth is irregular (see ΔT) and has a slowing trend; therefore atomic clocks constitute a much more stable timebase. On 1 January 1972, GMT was superseded as the international civil time standard by Coordinated Universal Time, maintained by an ensemble of atomic clocks around the world. Universal Time (UT), a term introduced in 1928, initially represented mean time at Greenwich determined in the traditional way to accord with the originally defined universal day; from 1 January 1956 (as decided by the International Astronomical Union in Dublin in 1955, at the initiative of William Markowitz) this "raw" form of UT was re-labelled UT0 and effectively superseded by refined forms UT1 (UT0 equalised for the effects of polar wandering)[10] and UT2 (UT1 further equalised for annual seasonal variations in Earth rotation rate).

Indeed, even the Greenwich meridian itself is not quite what it used to be—defined by "the centre of the transit instrument at the Observatory at Greenwich". Although that instrument still survives in working order, it is no longer in use and now the meridian of origin of the world's longitude and time is not strictly defined in material form but from a statistical solution resulting from observations of all time-determination stations which the BIPM takes into account when co-ordinating the world's time signals. Nevertheless, the line in the old observatory's courtyard today differs no more than a few metres from that imaginary line which is now the prime meridian of the world.

— Howse, D. (1997). Greenwich time and the longitude. London: Philip Wilson.

Ambiguity in the definition of GMT

Historically, GMT has been used with two different conventions for numbering hours. The long-standing astronomical convention, dating from the work of Ptolemy, was to refer to noon as zero hours (see Julian day). This contrasted with the civil convention of referring to midnight as zero hours dating from the Roman Empire. The latter convention was adopted on and after 1 January 1925 for astronomical purposes, resulting in a discontinuity of 12 hours, or half a day. The instant that was designated as "December 31.5 GMT" in 1924 almanacs became "January 1.0 GMT" in 1925 almanacs. The term Greenwich Mean Astronomical Time (GMAT) was introduced to unambiguously refer to the previous noon-based astronomical convention for GMT.[11] The more specific terms UT and UTC do not share this ambiguity, always referring to midnight as zero hours.

GMT in legislation

United Kingdom

Legally, the civil time used in the UK is called "Greenwich mean time" (without capitalisation), according to the Interpretation Act 1978, with an exception made for those periods when the Summer Time Act 1972 orders an hour's shift for daylight saving. The Interpretation Act 1978, section 9, provides that whenever an expression of time occurs in an Act, the time referred to shall (unless otherwise specifically stated) be held to be Greenwich mean time. Under subsection 23(3), the same rule applies to deeds and other instruments.[9]

During the experiment of 1968 to 1971, when the British Isles did not revert to Greenwich Mean Time during the winter, the all-year British Summer Time was called British Standard Time (BST).

In the UK, UTC+00:00 is disseminated to the general public in winter and UTC+01:00 in summer.[12][4]

BBC radio stations broadcast the "six pips" of the Greenwich Time Signal. It is named from its original generation at the Royal Greenwich Observatory, is aligned to Coordinated Universal Time, and called either Greenwich Mean Time or British Summer Time as appropriate for the time of year.

Other countries

Several countries define their local time by reference to Greenwich Mean Time.[13][14] Some examples are:

- Belgium: Decrees of 1946 and 1947 set legal time as one hour ahead of GMT.[13]

- Ireland: Standard Time (Amendment) Act, 1971, section 1, and Interpretation Act 2005, part iv, section 18(i).

- Canada: Interpretation Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. I-21, section 35(1). This refers to "standard time" for the several provinces, defining each in relation to "Greenwich time", but does not use the expression "Greenwich mean time". Several provinces, such as Nova Scotia (Time Definition Act. R.S., c. 469, s. 1), have their own legislation which specifically mentions either "Greenwich Mean Time" or "Greenwich mean solar time".

Time zone

Greenwich Mean Time is used as standard time in the following countries and areas, which also advance their clocks one hour (GMT+1) in summer.

- United Kingdom, where the summer time is called British Summer Time (BST)

- Republic of Ireland, where it is called Irish Standard Time (IST)[15] — officially changing to GMT in winter.

- Portugal (with the exception of the Azores)

- Canary Islands (Spain)

- Faroe Islands

Greenwich Mean Time is used as standard time all year round in the following countries and areas:

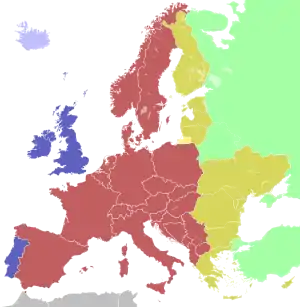

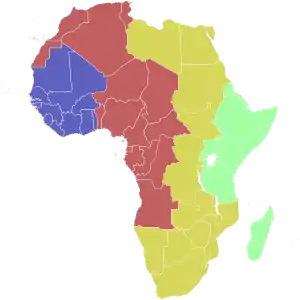

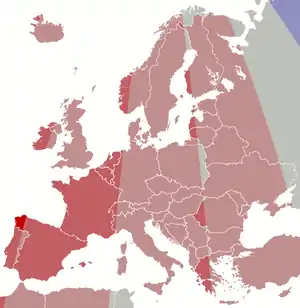

Discrepancies between legal GMT and geographical GMT

| Colour | Legal time vs local mean time |

|---|---|

| 1 h ± 30 m behind | |

| 0 h ± 30 m | |

| 1 h ± 30 m ahead | |

| 2 h ± 30 m ahead | |

| 3 h ± 30 m ahead |

Since legal, political, social and economic criteria, in addition to physical or geographical criteria, are used in the drawing of time zones, actual time zones do not precisely adhere to meridian lines. The "GMT" time zone, were it determined purely by longitude, would consist of the area between meridians 7°30'W and 7°30'E. However, in much of Western and Central Europe, despite lying between those two meridians, UTC+1 is used; similarly, there are European areas that use UTC, even though their physical time zone is UTC−1 (e.g. most of Portugal), or UTC−2 (the westernmost part of Iceland). Because the UTC time zone in Europe is shifted to the west, Lowestoft in the United Kingdom, at only 1°45'E, is the easternmost settlement in Europe in which UTC is applied. Following is a list of the incongruencies:

Countries and areas west of 22°30'W ("physical" UTC−2) that use UTC

- The westernmost part of Iceland, including the northwest peninsula (the Westfjords) and its main town of Ísafjörður, which is west of 22°30'W, uses UTC. Bjargtangar, Iceland is the westernmost point in which UTC is applied.

Countries and areas west of 7°30'W ("physical" UTC−1) that use UTC

- Canary Islands (Spain)

- Most of Portugal, including Lisbon, Porto, Braga, Aveiro, and Coimbra. (Only the easternmost part, including cities such as Bragança and Guarda, lies east of 7°30'W.) Since the Treaty of Windsor in 1386 (the world's oldest diplomatic alliance), Portugal has maintained close ties to the UK, which possibly explains its choice of UTC. Madeira, even further to the west, also employs UTC. A more likely explanation is that during the mid-1970s, when Portugal was on Central European Time all year round, it did not begin to get light in Lisbon in winter until 08:30.

- The western part of Ireland, including the cities of Cork, Limerick, and Galway

- Westernmost tip of Northern Ireland, including the county town of County Fermanagh, Enniskillen

- Extreme westerly portion of the Outer Hebrides, in the west of Scotland; for instance, Vatersay, an inhabited island and the westernmost settlement of Great Britain, lies at 7°54'W. If uninhabited islands or rocks are taken into account St Kilda, west of the Outer Hebrides, at 8°58'W, and Rockall, at 13°41'W, should be included.

- Westernmost island of the Faroe Islands (autonomous region of the Danish Kingdom), Mykines

- Iceland, including Reykjavík

- Northeastern part of Greenland, including Danmarkshavn

Countries (mostly) between meridians 7°30'W and 7°30'E ("physical" UTC) that use UTC+1

- Spain (except for the Canary Islands, which use UTC). Parts of Galicia lie west of 7°30'W ("physical" UTC−1), whereas there is no Spanish territory that even approaches 7°30'E (the boundary of "physical" UTC+1). Spain's time is the direct result of Franco's presidential order (published in Boletín Oficial del Estado of 8 March 1940)[16] abandoning Greenwich Mean Time and advancing clocks one hour, effective from 23:00 on 16 March 1940. This is an excellent example of political criteria used in the drawing of time zones: the time change was passed "in consideration of the convenience from the national time marching in step according to that of other European countries".[17][18] The presidential order (most likely enacted to be in synchrony with Germany and Italy, with which the Franco regime was unofficially allied) included in its 5th article a provision for its future phase out,[18] which never took place. Due to this political decision Spain is two hours ahead of its local mean time during the summer, one hour ahead in winter, which possibly explains the notoriously late schedule for which the country is known.[19] In Portugal, which is a mere one hour behind Spain, the timetable is quite different.

- Andorra

- Belgium

- Most of France, including the cities of Paris, Marseille and Lyon. Only small parts of Alsace, Lorraine and Provence are east of 7°30'E ("physical" UTC+1).

- Luxembourg

- Monaco

- Netherlands

See also

- Coordinated Universal Time

- Greenwich Time Signal

- Ruth Belville – the Greenwich Time Lady, daughter of John Henry Belville, who was in business of daily personal distribution of Greenwich Mean Time via a watch

- 24-hour watch – 24-hour wristwatch

- Radio clock

- Marine chronometer – synchronised with GMT, and used by ships to calculate their longitude

- Time in the United Kingdom

- Swatch Internet Time – alternative, decimal measure of time

- Western European Summer Time

Notes

- "Time scales". UCO Lick. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- "Coordinated Universal Time". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- Hilton and McCarthy 2013, pp. 231–2.

- McCarthy & Seidelmann 2009, p. 17.

- Astronomical Almanac Online 2015, Glossary s.v. "Universal Time".

- Howse 1997, p. 114.

- CLERK TO JUSTICES. "Time, Actual And Legal". Times, London, England, 14 May 1880: 10. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 18 August 2015.

- Bartky, Ian R. (2007). One Time Fits All: The Campaigns for Global Uniformity. Stanford University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0804756426. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- Myers (2007).

- UT1 as explained on IERS page

- Astronomical Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac. University Science Books. 1992. p. 76. ISBN 0-935702-68-7.

- Howse 1997, p. 157.

- Dumortier, Hannelore, & Loncke (n.d.)

- Seago & Seidelmann (2011).

- Standard Time Act, 1968.

- "BOE Orden sobre adelanto de la hora legal en 60 minutos". Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- "B.O.E. #68 03/08/1940 p.1675". Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- "B.O.E. #68 03/08/1940 p.1676". Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- "Hábitos y horarios españoles". Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

References

- Astronomical Almanac Online. (2015). United States Naval Observatory and Her Majesty's Nautical Almanac Office.

- Dumortier, J, Hannelore, D, & Loncke, M. (n.d.). "Legal Aspects of Trusted Time services in Europe". AMANO. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Guinot, Bernard (August 2011). "Solar time, legal time, time in use". Metrologia 48 (4): S181–185. Bibcode:2011Metro..48S.181G. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/48/4/S08.

- Hilton, James L and McCarthy, Dennis D.. (2013). "Precession, Nutation, Polar Motion, and Earth Rotation." In Sean Urban and P. Kenneth Seidelmann (Eds.), Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac 3rd ed. Mill Valley CA: University Science Books.

- Howse, D. (1997). Greenwich time and the longitude. London: Philip Wilson.

- Interpretation Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. I-21. (2005). CanLII. (Canadian statute)

- Interpretation Act 1978. UK Law Statute Database. (UK statute)

- Interpretation Act 2005. British and Irish Legal Information Institute. (Irish statute)

- McCarthy, D., and Seidelmann, P. K. (2009). TIME—From Earth Rotation to Atomic Physics. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

- Myers, J. (2007). History of legal time in Britain. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- Seago, J.H., & Seidelmann, P. K. (2011). National Legal Requirements for Coordinating with Universal Time. Steve Allen of University of California Observatories. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "Six pip salute". BBC News. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- Standard Time Act, 1968. Irish Statute Book. Office of the Attorney General. (Irish statute)

- Standard Time (Amendment) Act, 1971. British and Irish Legal Information Institute. (Irish statute)

External links

- Greenwich Mean Time

- Interactive World Clock Map

- International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service

- Royal Observatory, Greenwich

- The original BBC World Service GMT time signal in MP3 format

- Rodgers, Lucy (20 October 2009). "At the centre of time". BBC News. Retrieved 20 October 2009.