Timeline of Orthodoxy in Greece (1204–1453)

This is a timeline of the presence of Orthodoxy in Greece. The history of Greece traditionally encompasses the study of the Greek people, the areas they ruled historically, as well as the territory now composing the modern state of Greece.

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

Latin occupation and end of Byzantium (1204–1453)

The beginning of Frangokratia: the division of the Byzantine Empire after the Fourth Crusade, 1204 AD.

Eastern Mediterranean c. 1230 AD.

- 1204 Fourth Crusade sacks Constantinople, laying waste to the city and stealing many relics and other items;[1][2][note 1][note 2] the Great Schism is generally regarded as having been completed by this act; Venetians use the imperial monastery of Christ Pantocrator as their headquarters in Constantinople.

- 1204 Latin Occupation of mainland Greece under Franks and Venetians begins: the Latin Empire of Constantinople, Latin Kingdom of Thessalonica, the Principality of Achaea, and the Duchy of Athens; the Venetians controlled the Duchy of the Archipelago in the Aegean; Othon de la Roche of Burgundy becomes Duke of Athens.[4][note 3]

- 1205 Latins annex Athens and convert the Parthenon into a Roman Catholic church – Santa Maria di Athene, later Notre Dame d'Athene.[note 4]

- 1211 Venetian crusaders conquer Byzantine Crete, retaining it until defeated by the Ottomans in 1669.

Saint John Vatatzes the Merciful King,[7] Emperor of Nicaea (1221–1254), and

"the Father of the Greeks."[8]

- 1224 The Byzantines recover Thessaloniki and surrounding area, under the Greek ruler of Epirus Theodore Komnenos Doukas.

- 1231 Burning of 13 monk-martyrs and Confessors of the Monastery of Panagia of Kantara, on Cyprus, defenders of leavened bread in the Eucharist, who suffered under the Latins.[9][10][11]

- 1234 Delegates of the two churches met first at Nicaea and then at Nymphaion (Asia Minor), negotiating the issues related to the union of the Churches, including dogmatic issues, however the dialogue came to a dead end.[12][note 5]

- 1235 Venerable saints Olympiada, abbess, and nun Euphrosyne martyred by pirates on Lesbos.[14][15]

- 1236 On the occasion of a joint Byzantine-Bulgarian siege of Latin Constantinople, Pope Gregory IX issued a crusading bull authorizing a crusade against the Byzantines under Emperor John Vatatzes.[12]

- c. 1238-63 Construction of the Church of Hagia Sophia in Trabzon, capital of the Empire of Trebizond, regarded as one of the finest examples of Byzantine architecture.[16][17]

- 1243 Decisive Mongol victory over the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum (with capital at Iconium), at the Battle of Köse Dağ.[18][note 6]

- 1249 Mystras citadel built by Franks in the Peloponnese.

- 1258 Michael VIII Palaiologos seizes the throne of the Nicaean Empire, founding the last Roman (Byzantine) dynasty, beginning reconquest of Greek peninsula from Latins.

- 1259 Byzantines defeat Latin Principality of Achaea at the Battle of Pelagonia, marking the beginning of the Byzantine recovery of Greece.

- 1261 End of Latin occupation of Constantinople and restoration of Orthodox patriarchs; Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos makes Mystras seat of the new Despotate of Morea, where a Byzantine renaissance occurred.

The Deësis mosaic with Christ as ruler, probably commissioned from 1261 to mark the end of 57 years of Roman Catholic use and the return to the Orthodox faith.

- 1265–1310 Arsenite Schism of Constantinople, beginning when Patr. Arsenius Autorianus excommunicated emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos.

- 1274 Orthodox clergy attending the Second Council of Lyon, accept supremacy of Rome and filioque clause.[note 7]

- 1275 Unionist Patr. of Constantinople John XI Beccus elected to replace Patr. Joseph I Galesiotes, who opposed Council of Lyon; Persecution of Athonite monks by Emp. Michael VIII and Patr. John XI Beccus.

- c. 1276–80 Venerable monk-martyrs of Iviron Monastery, martyred by the Latins.[21][22]

- 1279 Hieromonk Ieronymos Agathangelos writes an Apocalypse dealing with the destinies of the nations.[note 8]

- 1281 Pope Martin IV authorizes a Crusade against the newly re-established Byzantine Empire in Constantinople, excommunicating Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos and the Greeks and renouncing the union of 1274; French and Venetian expeditions set out toward Constantinople but are forced to turn back in the following year due to the Sicilian Vespers.

- 1282 Death of 26 martyrs of Zografou monastery on Mount Athos, martyred by the Latins.[23][24]

- 1285 Death of venerable martyrs Abbot Euthymius and twelve monks of Vatopedi, who suffered martyrdom for denouncing the Latinizing rulers Michael Paleologos (1261–1281) and John Bekkos (1275–1282) as heretics;[25][26] Council of Blachernae, convened and presided over by Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory II the Cypriot, condemns the actions of the eastern delegation at the false council of Lyons (1274) and also condemns the Franko-Latins who use of the filioque clause, thus officially repudiating the accommodation with Rome.[27][note 9]

- 1287 Last record of Western Rite Monastery of Amalfion (Monastery of Saint Mary of the Latins) on Mount Athos.[28]

- 1292 The monastery of St. Nicholas is founded on Ioannina Island by Michael Philanthropinos (who had served as the Metropolitan of Ioannina), being oldest of five Greek Orthodox monasteries established there between the 13th and 17th centuries.[29][note 10]

- 14th century "Golden Age" of Thessaloniki in both literature and art, many churches and monasteries built.[30]

A Frankish tower, dating to either the Burgundian or Catalan period, stood on the Acropolis of Athens among the ruins of the Parthenon, then a church dedicated to Saint Mary, until it was dismantled in 1874.

- 1300–1400 The "Chronicle of Morea" (Το χρονικό του Μορέως) narrates events of the establishment of feudalism in mainland Greece, mainly in the Morea/Peloponnese, by the Franks following the Fourth Crusade, covering a period from 1204 to 1292.[31][32][33]

- 1309 Rhodes falls to the Knights of St. John, who establish their headquarters there, renaming themselves the "Knights of Rhodes".

- 1310 Arsenite Schism of Constantinople is officially ended by the reconciliation of the Arsenites to the Josephites, in a dramatic ceremony at Hagia Sophia on 14 Sep 1310.[34]

- 1311 Battle of Kephissos: Athens was conquered by the Catalan Company, a band of mercenaries called Almogavars, who made Catalan the official language and replaced the French and Byzantine-derived laws of the Principality of Achaea with the laws of Catalonia.[35][36][note 11]

Saint Gregory Palamas, Abp. of Thessaloniki (1347–1359) and "Pillar of Orthodoxy".[note 12]

- 1314 Foundation of the Monastery of the Nativity of the Theotokos in Kleisoura, Kastoria.[38]

- c. 1320 Death of Righteous Gerasimos, Ascetic of Euboea, Orthodox missionary in Greece in the period of the Frankokratia.[39][40]

- 1321-28 Byzantine civil war.[41]

- 1326 The city of Prussa in Asia Minor falls to the Ottomans after a nine-year siege.[42]

- c. 1326–1330 The Ottoman Janissary corps is first created by Sultan Orhan I, under the patronage of the Sufi Mystic Haji Bektas, converting many to Islam.[43][44][note 13][note 14]

- 1329 Greek monk and wonderworker St. Sergius of Valaam co-founded the Valaam Monastery (along with Herman of Valaam), in Russian Karelia on Valaam island, and is credited with bringing Orthodox Christianity to the Karelian and Finnish people.[note 15]

- 1331 The city of Nicaea, capital of the Empire only 100 years previously, falls to the Ottomans.[49]

- 1336 Meteora in Greece are established as a center of Orthodox monasticism, with the founding of the Great Meteoron Monastery.[50]

- 1337 Nicomedia captured by Ottomans.[51]

- 1338 Gregory Palamas writes Triads in defense of the Holy Hesychasts, defending the Orthodox practice of hesychast spirituality and the use of the Jesus Prayer.[52][note 16]

- 1341–47 Byzantine Civil war between John VI Cantacuzenus (1347–54) and John V Palaeologus (1341–91), sometimes referred to as the Second Palaiologan Civil War.[54]

- 1341–51 Six patriarchal sessions of the Ninth Ecumenical Council held in Constantinople,[note 17] convened by Roman Emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos, presided over by Ecumenical Patriarch John Kalekas and attended by the Patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem, and several bishops and abbots, including St. Gregory Palamas, through which the Orthodox Church affirmed the hesychastic theology of Gregory Palamas and condemned rationalistic philosophy of Barlaam of Calabria and the Akindynite heresy.[55][56][note 18]

- 1345 Byzantine jurist Constantine Harmenopoulos compiles the Hexabiblos in six volumes from a wide range of Byzantine legal sources.[58][note 19]

- 1346 Council of Adrianople, convened and presided over by Patriarch Lazarus of Jerusalem, and attended by several Thracian bishops, deposes Ecumenical Patriarch John Kalekas for supporting and ordaining the condemned heretic, Gregory Akindynos.[56][note 20]

- c. 1351 Holy Royal Patriarchal Stavropegic Monastery of the Vlatades (Moni Vlatadon) is founded in Thessaloniki.[59]

- 1354 Byzantine Mesazon and theologioan Demetrios Kydones, a Thomist, or Latinizer, translated the Summa contra Gentiles of Thomas Aquinas into Greek;[60][note 21] Ottomans make first settlement in Europe at Gallipoli.[49]

- 1359 Death of Gregory Palamas the Wonderworker, Abp. of Thessaloniki;[62] the first Greek Metropolitan is appointed in Wallachia, and between 1381-1386 in Moldavia.[63]

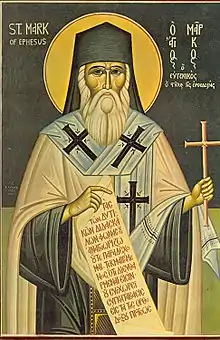

Saint Mark of Ephesus, "Pillar of Orthodoxy".[note 12]

- 1360 Death of Venerable Saint John Kukuzelis the Hymnographer.[64]

- c. 1361–1365 Ottoman Sultan Murad I formalized the famous corps of Janissaries by exacting a tribute ("child levy" – Devşirme) in children from Orthodox Christian subjects in the Balkans, conscripting the flower of Orthodox Christendom before adolescence, converting them to Islam and raising them to become Muslim soldiers and administrators.[44][65][note 22]

- 1362 Adrianople fell to the Ottomans and served as the forward base for Ottoman expansion into Europe.[67]

- 1374 Dionysius the Hagiorite (Denys de Korisos) obtains a Chrysobull from Alexios III Comnenus, Emperor of Trebizond, founding the Monastery of Dionysiou.[68][69]

- 1383 The Ottoman Turks seize Mount Athos.[68]

- 1386-7 Church of St Athanasius of Mouzaki built in Kastoria, Greece.[70][71]

- 1390 Ottomans take Philadelphia, last significant Byzantine enclave in Anatolia.[49]

- c. 1391–1394 In a Dialogue with a Learned Moslem, Byzantine emperor Manuel II Paleologus commented on such issues as forced conversion, holy war, and the relationship between faith and reason.[72][73][note 23]

- 1392 Death of Nicholas Kabasilas, well known theological writer and mystic of the Orthodox Church who took the side of the monks of Mount Athos and St Gregory Palamas in the Hesychast controversy.[74]

- 1394–1402 Ottomans unsuccessfully besiege and blockade Constantinople for the first time.[49]

- 15th century By the 15th century, only 17 metropolitanates, 1 archbishopric, and 3 bishoprics survived in Anatolia (Asia Minor), an area that had at one time possessed over 50 metropolitanates and more than 400 bishoprics.[75]

- 1403 After the Turks are defeated at the Battle of Ankara (1402),[49][note 24] Mount Athos is restored to Byzantine sovereignty.[68]

- 1406 Manuel II Palaeologus issues the third Typikon of Mount Athos.[68]

- 1411 Death of Niphon of Mount Athos, proponent of hesychastic theology and wonderworker.[76]

The right-believing Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos the Ethnomartyr (1449–1453).

- 1416 Ottoman fleet is destroyed by Venetians at Gallipoli.[49]

- 1422 Second unsuccessful Ottoman siege of Constantinople.[49][77][78]

- 1423-30 Thessaloniki was under Venetian control.[49]

- 1424 A delegation of Athonite monks visits Sultan Murad II, in Adrianople.[68]

- 1426 Death of New Martyr Ephraim of Nea Makri, a saint "newly revealed" ("νεοφανείς") in 1950.[79][80]

- 1429 Death of Symeon of Thessaloniki, Archbishop of Thessaloniki.[81]

- 1430 Ottomans final capture of Thessaloniki;[49][82][note 25] the monks of Mount Athos submit to Sultan Murad II and keep their autonomy.[83][note 26]

- 1438 Ottoman Sultan Murad II officially codified the Devşirme system of levying taxes in the form of Christian youths from the empire, involving enforced conversion to Islam.[45][note 27][note 28]

- 1439 Saint Mark of Ephesus courageously defended Orthodoxy at the Council of Florence, being the only Eastern bishop to refuse to sign the decrees of the council, regarded as a "Pillar of Orthodoxy" by the Church;[87][88] Council of Florence unsuccessfully tries to unite the Greek East and Latin West.[89]

- 1443 Council of Jerusalem, attended by the Orthodox Patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem condemened the union that was pronounced at the Council of Florence and threatened to excommunicate the Emperor and all who adhered to it, denouncing Metrophanes II of Constantinople as a heretic, and cancelling his Ordinations.[90]

- 1448 Council of Russian hierarchs in Moscow elects Jonah of Riazan as Metropolitan of Kiev and all Russia, being the first independent Metropolitan of Moscow and all Rus', having been appointed without the approval of the Patriarch in Constantinople as was the norm.[56][91][note 29]

- 1450 Death of Empress Helena Palaeologina (Saint Ypomoni of Loutraki);[92] Council of Constantinople convoked by Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos declined to accept the resolutions passed by the Council of Florence which were in favor of the union of the Greek and Latin churches.[93][94]

- 1452 Unification of Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox Churches in the cathedral of Hagia Sophia on 12 December, five months before the city fell, on the West's terms, when Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos, under pressure from Rome, allowed the union to be proclaimed by the former Metropolitan of Kiev Isidore, who had participated in the Council of Florence and was now a cardinal in the Roman Catholic Church, and who read the solemn promulgation of union and celebrated the union liturgy, including the name of the pope, arousing the greatest agitation among the population of the city;[95][96][note 30] death of Greek Byzantine philosopher and Renaissance humanist scholar George Plethon Gemistos (1353-1452), teacher of Basilios Bessarion, and one of the most challenging representatives of Greek learning who openly attempted to upset the balance between Greek thought and Christian dogma by advocating for the creation of a new religion based on Neoplatonism.[97][98][note 31]

- 1453 Constantinople falls to the Ottomans, ending Roman Empire;[100] on the eve of the fall of the city the last Megas Doux of the Byzantine Empire Loukas Notaras remarked: "better the turban of the Turk than the tiara of the Latin [pope];"[101][note 32] Hagia Sophia turned into a mosque;[103][104][note 33] [note 34] martyrdom of Constantine XI Palaiologos, last of the Byzantine Emperors;[106] of the 100,000 inhabitants of Constantinople, about 40,000 are supposed to have perished in the siege, and the Greek aristocracy was either then or immediately afterwards annihilated;[107] many Greek scholars escape to the West with books that become translated into Latin, triggering the Renaissance;[note 35] beginning of the genre of lamentation folk songs known as "Moirologia", or dirges (Byzantine secular music).[109][note 36]

See also

History

- History of the Orthodox Church

- History of Eastern Christianity

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church under the Ottoman Empire

- History of Eastern Orthodox Churches in the 20th century

- Timeline of Eastern Orthodoxy in America

Church Fathers

Notes

- "The Franks – occupying what now is France, Belgium and much of Central Europe – arrived in southern Greece early in the 13th century on the Fourth Crusade. The legions were diverted by their powerful Venetian financial backers to sack the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, the centre of Christian Orthodoxy."[1]

- "The Latin soldiery subjected the greatest city in Europe to an indescribable sack. For three days they murdered, raped, looted and destroyed on a scale which even the ancient Vandals and Goths would have found unbelievable. Constantinople had become a veritable museum of ancient and Byzantine art, an emporium of such incredible wealth that the Latins were astounded at the riches they found. Though the Venetians had an appreciation for the art which they discovered (they were themselves semi-Byzantines) and saved much of it, the French and others destroyed indiscriminately, halting to refresh themselves with wine, violation of nuns, and murder of Orthodox clerics. The Crusaders vented their hatred for the Greeks most spectacularly in the desecration of the greatest Church in Christendom. They smashed the silver iconostasis, the icons and the holy books of Hagia Sophia, and seated upon the patriarchal throne a whore who sang coarse songs as they drank wine from the Church's holy vessels. The estrangement of East and West, which had proceeded over the centuries, culminated in the horrible massacre that accompanied the conquest of Constantinople. The Greeks were convinced that even the Turks, had they taken the city, would not have been as cruel as the Latin Christians. The defeat of Byzantium, already in a state of decline, accelerated political degeneration so that the Byzantines eventually became an easy prey to the Turks. The Crusading movement thus resulted, ultimately, in the victory of Islam, a result which was of course the exact opposite of its original intention."[3]

- The "conquest by the western Franks of the Fourth Crusade is often seen as the beginning of the end, and its impact on the state of mind of the subjects of the empire was immense. For the next 200 years – and beyond – various parts of what had historically been the Byzantine empire were to be ruled, for varying lengths of time, by these crusaders and their descendants. For centuries, the emperors of Constantinople had held these territories, but now, remarkable quickly, they changed hands and the peasants and local lords of the conquered areas had to become accustomed to new masters who, at least at the beginning, spoke little or no Greek, had some startlingly different ways of arranging society and everyday life and, not least, had a church and religion which was Christian but very different from the ‘Orthodox’ Christianity of the empire."[5]

- "From 1205 to 1456, Athens was ruled by Burgundians, Catalans, Florentines, and, briefly, Venetians. The Parthenon was accorded great honor by them too. In the late thirteenth century, pope Nicolaus IV granted an indulgence for those who went on pilgrimage to it."[6]

- "In consequence of a communication which he received from Vatatzes through the Patriarch Germanus, the Pope sent to Nice, A.D. 1233, two Dominican and two Franciscan friars to discuss points of agreement. The envoys were received with great honour, and the Emperor assembled a Council at Nymphaeum. No sooner had they got to work, than both Greeks and Latins brought forward mutual accusations and invectives. The Latins complained of the Greeks condemning the Latin Azyms; of their purifying their Altars after Latin Celebrations; rebaptizing Latins; and of their erasure of the Pope's name from the Diptychs. The Patriarch met the charges with a counter accusation, viz., the desecration by the Latins of Greek Churches and Altars and vessels after the conquest of Constantinople...But the two chief points of discussion were the Azyms and the double Procession."[13]

- The defeat resulted in a period of turmoil in Anatolia and led directly to the decline and disintegration of the Seljuk state. The Empire of Trebizond became a vassal state of the Mongol empire. Furthermore the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia became a vassal state of the Mongols.[19] Real power over Anatolia was exercised by the Mongols.[20] After a long period of fragmentation, Anatolia was unified by the Ottoman dynasty.

- Emperor Michael VIII forced the Orthodox delegation to give in to the papal claims and filioque clause in order to form a swift union enabling the unified Christian world to defeat the Muslim threat.

- Ieronymos Agathangelos flourished in 1279 AD. He was a priest-monk and confessor, born in Rhodes. He lived in a cenobitic monastery for 51 years. In his 79th year of age he was, as he says, at Messina of Sicily, and at dawn on the Sunday of Orthodoxy he experienced a majestic vision by which several prophecies were foretold him. These were copied by an Italian monk in Messina in 1555, then translated into Latin by Theoklitos Polyidis, who distributed them around northern Europe, and then translated into Modern Greek in 1751 and printed in various editions in Venice.

- "A new patriarch, Gregory II from Cyprus (c.1241-1290), was installed, and one of his first acts was to depose all bishops who had supported the forced union of the churches and suspend all clerics ordained by the former patriarch (John Beccus). The unionists were still strong enough to call for a full airing of their case. Gregory agreed, and a council was convened in 1285 in the imperial palace of Blachernae,...the majority of those participating in the Council of Blachernae sided with Gregory against the unionists. Their position was published in the final statement of the Council, the Tomus, which was penned by Gregory.[27]

- A remarkable fresco shows the wise men of antiquity – Plato, Apollonius, Solon, Aristotle, Plutarch, Thucydides – "bearing witness, in a house in Athens, to the Divine resurrection and Presence of Christ."[29]

- "In connection with the Council of Vienne (1311–1312) the papal vice-chancellor, Cardinal Arnold Novelli, urged that the powerful and strategically placed Company be made the spearhead for a great crusade against Byzantine and Turk."[37]

- Saints Photius the Great, Mark of Ephesus, and Gregory Palamas, have been called the Three Pillars of Orthodoxy.

- The Janissaries were supposedly founded in 1326 when new recruits were set apart by Haci Bektas.[45] Bektashism spread from Anatolia through the Ottomans primarily into the Balkans, where its leaders (known as dedes or babas) helped convert many to Islam. The Bektashi Sufi order became the official order of the elite Janissary corps after their establishment.

- "What, more than anything, contributed to the spread of the Ottoman power, was the fiendish institution by Orkhan of the tribute of Christian children. Thus was formed the famous corps of Janissaries, or new soldiers. The strongest and most promising boys were, at ages between six and nine years, torn away from their families, cut off from every Christian tie, and educated so as to know no other than the Mahometan faith, to abjure which, afterwards, subjected them to the punishment of renegades, certain death. They were trained in the profession of arms to fight against enemies of the same Christian birth as themselves, and grew up to be the best soldiers in the Turkish armies, from whom their Generals and Governors were selected. So that the conquest of Eastern Christendom was really effected through soldiers born of Christian parents."[46]

- Conflicting church traditions place him possibly as early as the 10th century (c. 992), or as late as the 14th. His feast day is celebrated on 28 June.[47][48]

- "Gregory Palamas's doctrine of the Divine Energies not only provided the dogmatic basis to the Greek view of mysticism. It was also a restatement of the traditional interpretation of the Greek Fathers' theory of God's relation to man. It came to be accepted by a series of fourteenth-century Councils as the official doctrine of the Greek Church. To Western theologians it seemed to be clear heresy. It could not be reconciled with Thomism, which many Greeks were beginning to regard with sympathy."[53]

- The six sessions were held in Constantinople on:

- 10 June 1341;

- August 1341;

- 4 November 1344;

- 1 February 1347;

- 8 February 1347;

- 28 May 1351.[55]

- "Hesychast spirituality is still practiced by Eastern Christians and is widely popular in Russia through the publication of a collection of Hesychast writings, known as the Philokalia, in Greek in 1783 at Venice and in Slavonic in 1793 at St. Petersburg."[57]

- First printed 1540 in Paris, the Hexabiblos was widely adopted in the Balkans under the Ottoman Empire. In 1828, it was also adopted as the interim civil code in the newly independent Greek State.

- Gregory Akindynos had taken the opposite extreme to Barlaam of Calabria, believing that the Light of Mt. Tabor is the divine essence itself, rather than God's uncreated grace and energy, distinct from His divine essence. He was condemned at the second session, in August 1341. In the sixth and final session of the Council on 28 May 1351, the Anti-Palamites were condemned and the Akindynite heresy was brought to an end.[56]

- "Kydones' translations of Aquinas' works tried to assert their philosophical and theological superiority while a strong Greek philosophical tradition was still capable of refuting his rationalism...The first Thomists, or Latinizers, could not appreciate the blossoming of Greek thought and art in the fourteenth century, which synthesized ten centuries of tradition. They were contemporaries of Gregory Palamas yet preferred Thomas Aquinas, even though philosophy, painting, architecture, political and social institutions, and popular culture were all of the highest standard in the East."[61]

- "The first Janissaries were prisoners of war and slaves. After the 1380s, their ranks were filled under the devshirme system. The recruits were mostly Christian boys preferably 14 to 18 years old; however, boys ranging from 8 to 20 years old could be taken. Initially, the recruiters favored Greeks and Albanians, but, as the Ottoman Empire expanded into southeastern Europe and north, the devshirme came to include Albanians, Bulgarians, Georgians, Armenians, Croats, Bosnians, and Serbs and later Romanians, Poles, Ukrainians, and southern Russians."[66]

- Emperor Manuel II Paleologus stated: "Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached." The passage originally appeared in the Dialogue Held with a Certain Persian, the Worthy Mouterizes, in Anakara of Galatia. "When Manuel II composed the Dialogue (which Pope Benedict XVI excerpted on 12 September 2006), the Byzantine ruler was little more than a glorified dhimmi vassal of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid, forced to accompany the latter on a campaign through Anatolia...During the campaign he was conscripted to join, Manuel II witnessed with understandable melancholy the great metamorphosis–ethnic and toponymic–of formerly Byzantine Asia Minor. The devastation, and depopulation of these once flourishing regions was so extensive that often, Manuel could no longer tell where he was. The still recognizable Greek cities whose very names had been changed into something foreign became a source of particular grief. It was during this unhappy sojourn that Manuel II's putative encounter with a Muslim theologian occurred, ostensibly in Ankara. Manuel II's Dialogue was one of the later outpourings of a vigorous Muslim–Christian polemic regarding Islam's success, at (especially Byzantine) Christianity's expense, which persisted during the 11th through 15th centuries, and even beyond. The Muslim advocates' (particularly the Turks) most prominent argument was the indisputable evidence of Islam's military triumphs over the Christians of Asia Minor (especially Anatolia, in modern Turkey). These jihad conquests were repeatedly advanced in the polemics of the Turks. The Christian rebuttal, in contrast, hinged upon the ethical precepts of Muhammad and the Koran. Christian interlocutors charged the Muslims with abiding a religion which both condoned the life of a 'lascivious murderer', and claimed to give such a life divine sanction. Manuel, and generations of Christian interlocutors, argued that the 'Christ–hating' barbarians could never overcome the 'fortress of belief,' despite seizing lands and cities, extorting tribute and even conscripting rulers to perform humiliating services. Manuel II's discussions with his Muslim counterpart simply conformed to this pattern of polemical exchanges, repeated often, over at least four centuries."[73]

- Bayezid I was defeated and taken prisoner by Timur (Tamerlane) at the Battle of Ankara (1402). As a result of the Ottoman defeat the Anatolian Turkish emirates regained independence and the Byzantine Empire ceased being tributary and recovered substantial territory.[49]

- Beginning on 29 March 1430, the Ottoman sultan Murad II began a three-day siege of Thessalonica, resulting in the conquest of the city by the Ottoman army, and the taking of 7,000 inhabitants as slaves. The Venetians agreed to a peace treaty and withdrew from the region in 1432, leaving the Ottoman's with permanent dominion over the region.

- "From 1204 through 1430, the monks of Mount Athos struggled relentlessly against all ecumenism with the Catholics, which at that time was called "the union of the Churches." They were finally saved from Papal designs by the Ottoman Murat II, who, in occupying Thessaloniki in 1430, received at the same time the support of Mount Athos and who, in exchange, renewed the privileges confirmed later by the Fatih (Mehmet the Conqueror). The decrees of the Sultans called Mount Athos "the country where, night and day, the Name of God is blessed and which is the refuge of the poor and strangers.""[84]

- "The devshirme – in practice if not in theory – also involved virtually enforced conversion to Islam, which was certainly contrary to Islamic law. This devshirme system probably began in the 1380s, though the word itself did not appear in written records until 1438, around the time infantry and cavalry recruited in this way became military elite...In its fully developed form this devshirme system enlisted between 1,000 and 3,000 youths per year."[85]

- "It is the "child levy" (Devşirme) that most fully demonstrates the situation of the Christians as (the) object of long-term Islamisation intentions, carried out under compulsion."[86]

- The autocephaly of the Russian Orthodox Church, declared in 1448, was formally recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople only in 1589. After the beginning of the autocephaly of the Eastern Russian dioceses which were part of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, from 1461 the metropolitans who held the chair in Moscow began to be called Metropolitans of Moscow and all Russia (1461-1589). On the other hand the metropolitans west of there, who had residences in Navahrudak, Kiev and Vilnius, began to be called Metropolitans of Kiev, Galicia and All Ruthenia, remaining under the Ecumenical Patriarchate from 1458-1596 and again from 1620-1675.

- Although some of the Greek party, especially Bessarion, Metropolitan of Nicaea, and Isidore, former Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus', showed real concern for unity, they could not rally support for it in the East. The Patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem and the churches of Russia, Romania, and Serbia all rejected it immediately. In Byzantium only a small minority accepted it. Emperors John VIII and Constantine IX (1448–1453) proved unable to force their will on the Church. Most Byzantines felt betrayed.[96]

- Nearly all of his writing is marked by passionate devotion to Greece and a desire to restore its ancient glory.[99]

- "The refrain 'Better the turban of the Turk than the tiara of the Pope' was used by peasants in the Balkans who, for so long, had been exploited by the Roman Catholic nobles."[102]

- One of the Ulama climbed the pulpit and recited the Shahada. "About forty other Churches were in like manner converted into Mosques, Mahomet allowing the Greek Church to celebrate its rites in the remainder."[105]

- After the fall of Constantinople, Hagia Sophia ceased to be the most important church for the Russians as it was replaced by the Church of the Resurrection (Church of the Holy Sepulchre) of Jerusalem.

- "Any reassessment of the role of the émigré Byzantine scholars in the development of Italian Renaissance thought and learning must recognize that at the time of the development of the Italian Renaissance there was also a parallel 'Renaissance' taking place in the Byzantine East. The latter, more accurately termed the Palaeologan 'revival of thinking', had begun earlier, in the thirteenth century. This revival of culture under the Palaeologan dynasty was expressed in the emergence of certain 'realistic' qualities in painting, a further development in mystical beliefs, and...a greater intensification than ever before of the study of Ancient Greek literature, philosophy, and science."[108]

- The Byzantine historian Doukas, imitating the "lamentation" of Nicetas Acominatus after the Sack of Constantinople by the Latins in 1204, bewailed the event of 1453. He began his lamentation:

- "O, city, city, head of all cities! O, city, city, center of the four quarters of the world!

- O, city, city, pride of the Christians and ruin of the barbarians! O, city, city, second

- paradise planted in the West, including all sorts of plants bending under the burden of

- spiritual fruits! Where is thy beauty, O, paradise? Where is the blessed strength of spirit

- and body of thy spiritual Graces? Where are the bodies of the Apostles of my Lord?

- Where are the relics of the saints, where are the relics of the martyrs? Where is the

- corpse of the great Constantine and other Emperors..."[110]

References

- Brian Murphy. "East might meet West in ancient grave site Find may clarify a key period of Greek history, when the Christian Orthodox and Ottoman Empires met." The Globe and Mail [Toronto, Ont]. 12 July 1997. Page A.8.

- Thomas F. Madden. "Vows and Contracts in the Fourth Crusade: The Treaty of Zara and the Attack on Constantinople in 1204." The International History Review. 15.3 (Aug. 1993): pp.441–68.

- Speros Vryonis. Byzantium and Europe. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1967. p.152.

- Michael Llewellyn-Smith (2004). "Chronology". Athens: A Cultural and Literary History. USA: Interlink Books. p. xv. ISBN 978-1-56656-540-0.

- Gill Page. "The Frankish conquest of Greece." In: Being Byzantine: Greek Identity Before the Ottomans, 1200-1420. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Prof. Anthony Kaldellis. A Heretical (Orthodox) History of the Parthenon. Department of Greek and Latin, The Ohio State University. 01/02/2007.

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Ἰωάννης ὁ Βατατζὴς ὁ ἐλεήμονας βασιλιὰς. 4 Νοεμβρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- A.A. Vasiliev. History of the Byzantine Empire. Vol. 2. University of Wisconsin Press, 1971. pp.531–534.

- May 19/June 1. Orthodox Calendar (PRAVOSLAVIE.RU).

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Οἱ Ἅγιοι Βαρνάβας, Γεννάδιος, Γεράσιμος, Γερμανός, Θεόγνωστος, Θεόκτιστος, Ἱερεμίας, Ἰωάννης, Ἰωσήφ, Κόνων, Κύριλλος, Μάξιμος καὶ Μάρκος οἱ Ὁσιομάρτυρες. 19 Μαΐου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- The Thirteen Holy Martyrs of Kantara in Cyprus: Defenders of Leavened Bread in the Eucharist. Mystagogy Resource Center. 19 May 2010.

- Banev Guentcho. John III Vatatzes. Transl. Koutras, Nikolaos. Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor (EHW). 12/16/2002. Retrieved: 7 November 2011.

- Rev. A. H. Hore. Eighteen centuries of the Orthodox Greek Church. London: James Parker & Co., 1899. p. 439.

- Great Synaxaristes (in Greek): Οἱ Ἁγίες Ὀλυμπία καὶ Εὐφροσύνη οἱ Ὁσιομάρτυρες. 11 Μαΐου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- May 11/24. Orthodox Calendar (PRAVOSLAVIE.RU). Retrieved: 10 July 2013.

- Eastmond, Anthony. "The Byzantine Empires in the Thirteenth Century". In: Art and Identity in Thirteenth-Century Byzantium: Hagia Sophia and the Empire of Trebizond. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004, p. 1.

- Erasing the Christian past: A fine Byzantine church in Turkey has been converted into a mosque. The Economist: Religion in Turkey. 27 July 2013. Retrieved: 3 September 2015.

- D.A. Zakythinós (Professor). The Making of Modern Greece: From Byzantium to Independence. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1976. p. 3. ISBN 9780631153603

- İdris Bal, Mustafa Çufalı: Dünden bugüne Türk Ermeni ilişkileri, Nobel, 2003, ISBN 9755914889, page 61.

- Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach-Medieval Islamic Civilization: A-K, index, p.442

- Great Synaxaristes (in Greek): Οἱ Ἅγιοι Ἰβηρίτες Ὁσιομάρτυρες. 13 Μαΐου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- Martyrs killed by the Latins at the Iveron Monastery on Mt. Athos. OCA – Feasts and Saints.

- Great Synaxaristes (in Greek): Οἱ Ἅγιοι 26 οἱ Ὁσιομάρτυρες Ζωγραφίτες τοῦ Ἁγίου Ὄρους. 10 Οκτωβρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- 26 Martyrs of the Zographou Monastery on Mt. Athos at the hands of the Crusaders. OCA – Feasts and Saints.

- Great Synaxaristes (in Greek): Ὁ Ὅσιος Εὐθύμιος Ἡγούμενος Μονῆς Βατοπαιδίου και οἱ σὺν αὐτῷ μαρτυρήσαντες 12 Μοναχοί. 4 Ιανουαρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- Venerable Euthymius Martyred at Vatopedi of Mt Athos. OCA – Feasts and Saints.

- Dale T. Irvin and Scott Sunquist. History of the World Christian Movement: Volume 1: Earliest Christianity To 1453. A&C Black, 2002. p. 444.

- Fr. Hieromonk Aidan Keller. Amalfion: Western Rite Monastery of Mt. Athos. A Monograph with Notes & Illustrations. St. Hilarion Press, 1994–2002.

- Fred A. Reed. "The Greece of Ali Pasha." The Globe and Mail [Toronto, Ont]. 10 February 1988. Page C.1.

- Byzantine churches (Unesco World Heritage Sites). Thessaloniki Convention & Visitors Bureau (TCVB). Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- French of Outremer: The Chronicle of Morea. Fordham University. Retrieved: 28 January 2013.

- Teresa Shawcross. The Chronicle of Morea: Historiography in Crusader Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- (in Greek) Ζέπος Π. "Το δίκαιον εις το Χρονικόν του Μορέως." Επετηρίς Εταιρείας Βυζαντινών Σπουδών. 18(1948), 202–220. (P. Zepos. "The Law in the Chronicle of the Morea." Annals of the Society for Byzantine Studies. 18(1948), 202–220.)

- Alexander P. Kahzdan (Ed). "Arsenites." The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 9780195046526

- William Miller. The Latins in the Levant: A History of Frankish Greece 1204–1566. Cambridge, Speculum Historiale, 1908. pp. 225-232.

- Kenneth Meyer Setton. Catalan Domination of Athens: 1311-1388. Revised. Variorum Reprints, 1975. 323 pages. ISBN 9780902089778

- R. Ignatius Burns. "The Catalan Company and the European Powers, 1305-1311." Speculum, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Oct., 1954), p. 757.

- (in Greek) ΙΕΡΑ ΜΟΝΗ ΓΕΝΕΘΛΙΟΥ ΘΕΟΤΟΚΟΥ ΚΛΕΙΣΟΥΡΑΣ ΚΑΣΤΟΡΙΑΣ. Μοναστήρια της Ελλάδας. Sunday, 9 September 2012. Retrieved: 22 December 2013.

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ὁ Ὅσιος Γεράσιμος ὁ ἐξ Εὐρίπου (Εὐβοίας). 7 Δεκεμβρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- (in Greek) Συναξαριστής. 7 Δεκεμβρίου. ECCLESIA.GR. (H ΕΚΚΛΗΣΙΑ ΤΗΣ ΕΛΛΑΔΟΣ).

- Angeliki E. Laiou. "The Byzantine empire in the fourteenth century." In: Michael Jones (Ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume VI c.1300 - c.1415. Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008. p. 804.

- Rogers, Clifford (2010). The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 261. ISBN 9780195334036.

- David Nicolle. The Janissaries. London: Osprey Publishing. pp.9–10. ISBN 9781855324138

- Benjamin Vincent. Haydn's Dictionary of Dates and Universal Information. 17th Edition. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1884. p.702.

- "The Kapıkulu Corps and Janissaries." TheOttomans.org. Retrieved: 15 February 2013.

- Rev. A. H. Hore. Eighteen centuries of the Orthodox Greek Church. London: James Parker & Co. 1899. pp. 453-454.

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Οἱ Ὅσιοι Σέργιος καὶ Γερμανός. 28 Ιουνίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- Venerable Sergius the Wonderworker of Valaam. OCA – Lives of the Saints.

- Gábor Ágoston and Bruce Masters. Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2009. p. 612.

- Dana Facaros, Linda Theodorou. Greece. Country and Regional Guides – Cadogan Series. New Holland Publishers, 2003. p. 510. ISBN 9781860118982

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, pp. 1483–1484, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- "Palamas, Saint Gregory." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- Steven Runciman. The Great Church in Captivity: A Study of the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the Eve of the Turkish Conquest to the Greek War of Independence. Cambridge University Press, 1968. pp. 100-101.

- Reinert, Stephen W. (2002). "Fragmentation (1204–1453)", in Mango, Cyril, The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 263, 265. ISBN 0-19-814098-3

- M.C. Steenberg. Gregory Palamas: Historical Timeline Archived 7 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Monachos.net: Orthodoxy through Patristic, Monastic & Liturgical Study. Retrieved: 24 February 2015.

- Stavros L. K. Markou. An Orthodox Christian Historical Timeline. Retrieved: 24 February 2015.

- "Hesychasm." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- D.A. Zakythinós (Professor). The Making of Modern Greece: From Byzantium to Independence. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1976. p. 49. ISBN 9780631153603

- "The Holy Royal Patriarchal Stavropegic Monastery of the Vlatades (Moni Vlatadon)." The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. retrieved: 28 January 2013.

- Christos Yannaras. Orthodoxy and the West: Hellenic Self-Identity in the Modern Age. Transl. Peter Chamberas and Norman Russell. Brookline: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2006. p.3.

- Christos Yannaras. Orthodoxy and the West: Hellenic Self-Identity in the Modern Age. Transl. Peter Chamberas and Norman Russell. Brookline: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2006. p.11.

- Great Synaxaristes (in Greek): Ὁ Ἅγιος Γρηγόριος ὁ Παλαμᾶς ὁ Θαυματουργός Ἀρχιεπίσκοπος Θεσσαλονίκης. 14 Νοεμβρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- D.A. Zakythinós (Professor). The Making of Modern Greece: From Byzantium to Independence. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1976. p. 101. ISBN 9780631153603

- Great Synaxaristes (in Greek): Ὁ Ὅσιος Ἰωάννης ὁ ψάλτης ὁ καλούμενος Κουκουζέλης. 1 Οκτωβρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- John Wilkes. Encyclopaedia Londinensis, or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature. Volume XXIV. London, 1829. p.148.

- Alexander Mikaberidze, (Professor). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2011. p.444. ISBN 9781598843361

- "Edirne." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- Treasures from Mount Athos. CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF IMPORTANT EVENTS. Hellenic Resources Network (HR-Net). Retrieved: 23 May 2013.

- Great Synaxaristes (in Greek): Ὁ Ὅσιος Διονύσιος κτίτωρ Ἱερᾶς Μονῆς Διονυσίου Ἁγίου Ὄρους. 25 Ιουνίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- (in Greek) Άγιος Αθανάσιος του Μουζάκη. Δήμος Καστοριάς (Kastoria City). Retrieved: 28 August 2013.

- Cvetan Grozdanov; Ǵorǵi Krsteski; Petar Alčev (1980). Ohridsko zidno slikarstvo XIV veka. Institut za istoriju umetnosti, Filozofski fakultet. p. 233. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- Manuel Paleologus. Dialogues with a Learned Moslem. (Transl. Roger Pearse, Ipswich, UK, 2009). Dialogue 7 (2009), Chapters 1–18 (of 37).

- Andrew G. Bostom. "The Pope, Jihad, and 'Dialogue'". American Thinker. 17 September 2006. Retrieved: 16 March 2013.

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ὁ Ὅσιος Νικόλαος Καβάσιλας. 20 Ιουνίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- Speros Vryonis. The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor: and the Process of Islamization from the Eleventh Through the Fifteenth Century. Volume 4 of Publications of the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. University of California Press, 1971. pp. 348-349. ISBN 9780520015975

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ὁ Ὅσιος Νήφων ὁ Καυσοκαλυβίτης. 14 Ιουνίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- Stanford J. Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 1, Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire 1280–1808. Cambridge University Press, 1976. p. 45.

- Edwin Pears. The Destruction of the Greek Empire And the Story of the Capture of Constantinople by the Turks. 1908. Reprinted Kessinger Publishing, 2004. pp. 114–115.

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Ἐφραὶμ ὁ Ἱερομάρτυρας ὁ ἐν Νέᾳ Μάκρῃ Ἀττικῆς. 5 Μαΐου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- New Martyr Ephraim. OCA – Feasts and Saints.

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Συμεὼν Ἀρχιεπίσκοπος Θεσσαλονίκης. 15 Σεπτεμβρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- cf. the account of John Anagnostes.

- Timeline of the History of the Greek Church. Anagnosis Books, Deliyianni 3, Marousi 15122, Greece. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- Dimitri Kitsikis (Professor). The Old Calendarists and the Rise of Religious Conservatism in Greece. Translated from the French by Novice Patrick and Bishop Chrysostomos of Etna. Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies, 1995. p. 21.

- Alexander Mikaberidze, (Professor). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2011. p.273. ISBN 9781598843361

- Evgeni Radushev. "PEASANT" JANISSARIES? Journal of Social History. Volume 42, Number 2, Winter 2008. p.448

- Great Synaxaristes (in Greek): Ὁ Ἅγιος Μᾶρκος ὁ Εὐγενικὸς Ἐπίσκοπος Ἐφέσου. 19 Ιανουαρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- St Mark the Archbishop of Ephesus. OCA – Feasts and Saints.

- Michael Angold (Ed.). Eastern Christianity. The Cambridge History of Christianity. Cambridge University Press, 2006. pp. 73–78. ISBN 9780521811132

- Rev. A. H. Hore. Eighteen centuries of the Orthodox Greek Church. London: James Parker & Co. 1899. p. 471.

- E. E. Golubinskii. Istoriia russkoi tserkvi. Moscow: Universitetskaia tipografiia, 1900, vol. 2, pt. 1, p. 469.

- Great Synaxaristes (in Greek): Ἡ Ὁσία Ὑπομονή. 29 Μαΐου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- Rev. John McClintock (D.D.),and James Strong (S.T.D.). Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature. Vol. II - C, D. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1868. p. 491.

- Andrew of Dryinoupolis, Pogoniani and Konitsa, and, Seraphim of Piraeus and Faliro. A Letter to Pope Francis Concerning His Past, the Abysmal State of Papism, and a Plea to Return to Holy Orthodoxy. HOLY AUTOCEPHALOUS ORTHODOX CATHOLIC CHURCH OF GREECE (THE HOLY METROPOLIS OF DRYINOUPOLIS, POGONIANI AND KONITSA, and, THE HOLY METROPOLIS OF PIRAEUS AND FALIRO). 10 April 2014. p. 4.

- Georgije Ostrogorski. History of the Byzantine State. Rutgers University Press, 1969. p.568.

- E. Glenn Hinson. The Church Triumphant: A History of Christianity up to 1300. Mercer University Press, 1995. p.443.

- Demetrios Constantelos. "A Conflict between Ancient Greek Philosophy and Christian Orthodoxy in the Late Greek Middle Ages." MYRIOBIBLOS. Retrieved: 7 November 2018.

- C. M. Woodhouse. George Gemistos Plethon: The Last of the Hellenes. Clarendon Press, 1986.

- "Gemistus Plethon, George." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- A. A. Vasiliev. History of the Byzantine Empire: 324–1453. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1958. pp. 650–653.

- Christopher Allmand, Rosamond McKitterick (Eds.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 7, C.1415-c.1500. Cambridge University Press, 1998. p. 782. ISBN 9780521382960

- Adam Francisco. Martin Luther and Islam: A Study in Sixteenth-century Polemics and Apologetics. Volume 8 of The History of Christian-Muslim Relations, ISSN 1570-7350. BRILL, 2007. p. 86. ISBN 9789004160439

- (in German) Wolfgang Müller-Wiener. Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn d. 17 Jh. Tübingen: Wasmuth, 1977. p. 91. ISBN 978-3-8030-1022-3.

- Steven Runciman. The Fall of Constantinople, 1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965. p. 149. ISBN 0-521-39832-0.

- Rev. A. H. Hore. Eighteen centuries of the Orthodox Greek Church. London: James Parker & Co. 1899. p. 476.

- Donald Nicol. The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453. Cambridge University Press, 1993 p. 369.

- Rev. A. H. Hore. Eighteen centuries of the Orthodox Greek Church. London: James Parker & Co. 1899. p. 478.

- Deno John Geanakoplos. Constantinople and the West: Essays on the Late Byzantine (Palaeologan) and Italian Renaissances and the Byzantine and Roman Churches. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1989. p.3. ISBN 9780299118846

- Margaret Alexiou, Dimitrios Yatromanolakis, Panagiotis Roilos. "Byzantine tradition and the laments for the fall of Constantinople." In: The Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition. 2nd Ed. Greek Studies: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Rowman & Littlefield, 2002. pp.85–90. ISBN 9780742507579

- A. A. Vasiliev. History of the Byzantine Empire: 324–1453. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1958. p.654.

Bibliography

- Aristeides Papadakis (with John Meyendorff). The Christian East and the Rise of the Papacy: The Church 1071–1453 A.D. The Church in History Vol. IV. Crestwood, N.Y. : St. Vladimirs Seminary Press, 1994.

- Deno John Geanakoplos. Byzantine East and Latin West: Two worlds of Christendom in Middle Ages and Renaissance: Studies in Ecclesiastical and Cultural History. Oxford Blackwell 1966.

- E. Brown. "The Cistercians in the Latin Empire of Constantinople and Greece." Traditio 14 (1958), pp. 63–120.

- Gill Page. Being Byzantine: Greek Identity before the Ottomans, 1200–1420. Cambridge University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-521-87181-5

- Joseph Gill. Church Union: Rome and Byzantium, 1204–1453. Variorum Reprints, 1979.

- Kenneth M. Setton. Catalan Domination of Athens, 1311–1388. Mediaeval Academy of America, 1948.

- Kenneth Meyer Setton. The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571: The Thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Volume 1. American Philosophical Society, 1976.

- N.G. Chrissis. Crusading in Frankish Greece: A Study of Byzantine-Western Relations and Attitudes, 1204-1282. Medieval Church Studies (MCS 22). Brepols Publishers, 2013. 338 pp. ISBN 978-2-503-53423-7

- P. Charanis. "Byzantium, the West and the Origin of the First Crusade." Byzantion 19 (1949), pp. 17–36.

- Prof. Tia M. Kolbaba. The Byzantine Lists: Errors of the Latins. 1st Ed. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000. 248pp.

- R. Wolff. "The Organisation of the Latin Patriarchate of Constantinople 1204–61." Traditio 6 (1948), pp. 33–60.

- Speros Vryonis, (Jr). "Byzantine Attitudes towards Islam during the Late Middle Ages." Greek Roman and Byzantine Studies 12 (1971).

- Stephanos Efthymiadis, (Open University of Cyprus, Ed.). The Ashgate Research Companion to Byzantine Hagiography: Volume I: Periods and Places. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., December 2011. 464 pp. ISBN 978-0-7546-5033-1

- Stephanos Efthymiadis, (Open University of Cyprus, Ed.). The Ashgate Research Companion to Byzantine Hagiography: Volume II: Genres and Contexts. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., March 2014. 536 pp. ISBN 978-1-4094-0951-9

- William Miller. The Latins in the Levant: A History of Frankish Greece 1204–1566. Cambridge, Speculum Historiale, 1908.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.