Toxaphene

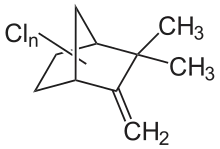

Toxaphene was an insecticide used primarily for cotton in the southern United States during the late 1960s and 1970s.[3][4] Toxaphene is a mixture of over 670 different chemicals and is produced by reacting chlorine gas with camphene.[3][5] It can be most commonly found as a yellow to amber waxy solid.[3]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Chlorocamphene, Octachlorocamphene, Polychlorocamphene, Chlorinated camphene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.348 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Density | 1.65 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 65 to 90 °C (149 to 194 °F; 338 to 363 K) |

| Boiling point | decomposition at 155 °C (311 °F; 428 K) |

| 0.0003% (20°C)[1] | |

| Vapor pressure | 0.4 mmHg (25°C)[1] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS pictograms |    |

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

| H301, H312, H315, H335, H351, H400, H410 | |

| P261, P273, P280, P301+310, P501 | |

| Flash point | noncombustible [1] |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

75 mg/kg (oral, rabbit) 112 mg/kg (oral, mouse) 250 mg/kg (oral, guinea pig) 50 mg/kg (oral, rat)[2] |

LCLo (lowest published) |

2000 mg/m3 (mouse, 2 hr)[2] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 0.5 mg/m3 [skin][1] |

REL (Recommended) |

Ca [skin][1] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

200 mg/m3[1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Toxaphene was banned in the United States in 1990 and was banned globally by the 2001 Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.[3][6] It is a very persistent chemical that can remain in the environment for 1–14 years without degrading, particularly in the soil.[7]

Testing performed on animals, mostly rats and mice, has demonstrated that toxaphene is harmful to animals. Exposure to toxaphene has proven to stimulate the central nervous system, as well as induce morphological changes in the thyroid, liver, and kidneys.[8]

Toxaphene has been shown to cause adverse health effects in humans. The main sources of exposure are through food, drinking water, breathing contaminated air, and direct contact with contaminated soil. Exposure to high levels of toxaphene can cause damage to the lungs, nervous system, liver, kidneys, and in extreme cases, may even cause death. It is thought to be a potential carcinogen in humans, though this has not yet been proven.[3]

Composition

Toxaphene is a synthetic organic mixture composed of over 670 chemicals, formed by the chlorination of camphene (C10H16) to an overall chlorine content of 67–69% by weight.[3][5][9] The bulk of the compounds (mostly chlorobornanes, chlorocamphenes, and other bicyclic chloroorganic compounds) found in toxaphene have chemical formulas ranging from C10H11Cl5 to C10H6Cl12, with a mean formula of C10H10Cl8.[10] The formula weights of these compounds range from 308 to 551 grams/mole; the theoretical mean formula has a value of 414 grams/mole. Toxaphene is usually seen as a yellow to amber waxy solid with a piney odor. It is highly insoluble in water but freely soluble in aromatic hydrocarbons and readily soluble in aliphatic organic solvents. It is stable at room temperature and pressure.[3] It is volatile enough to be transported for long distances through the atmosphere.[11][12]

Applications

Toxaphene was primarily used as a pesticide for cotton in the southern United States during the late 1960s and 1970s. It was also used on corn, small grains, vegetables, and soybeans to control ectoparasites such as lice, flies, ticks, mange, and scam mites on livestock. In some cases it was used to kill undesirable fish species in lakes and streams. The breakdown of usage can be summarized: 85% on cotton, 7% to control insect pests on livestock and poultry, 5% on other field crops, 3% on soybeans, and less than 1% on sorghum.[4]

The first recorded usage of toxaphene was in 1966 in the United States, and by the early to mid 1970s, toxaphene was the United States' most heavily used pesticide. Over 34 million pounds of toxaphene were used annually from 1966 to 1976. As a result of Environmental Protection Agency restrictions, annual toxaphene usage fell to 6.6 million pounds in 1982. In 1990, the EPA banned all usage of toxaphene in the United States.[4] Toxaphene is still used in countries outside the United States but much of this usage has been undocumented.[3] Between 1970 and 1995, global usage of toxaphene was estimated to be 670 million kilograms (1.5 billion pounds).[4]

Production

Toxaphene was first produced in the United States in 1947 although it was not heavily used until 1966. By 1975, toxaphene production reached its peak at 59.4 million pounds annually. Production decreased more than 90% from this value by 1982 due to Environmental Protection Agency restrictions. Overall, an estimated 234,000 metric tons (over 500 million pounds) have been produced in the United States. Between 25% and 35% of the toxaphene produced in the United States has been exported. There are currently 11 toxaphene suppliers worldwide.[4]

Environmental effects

When released into the environment, toxaphene can be quite persistent and exists in the air, soil, and water. In water, it can evaporate easily and is fairly insoluble.[3] Its solubility is 3 mg/L of water at 22 degrees Celsius.[13] Toxaphene breaks down very slowly and has a half-life of up to 12 years in the soil.[6] It is most commonly found in air, soil, and sediment found at the bottom of lakes or streams.[3] It can also be present in many parts of the world where it was never used because toxaphene is able to evaporate and travel long distances through air currents. Toxaphene can eventually be degraded, through dechlorination, in the air using sunlight to break it down. The degradation of toxaphene usually occurs under aerobic conditions.[6] The levels of toxaphene have decreased since its ban, however, due to its persistence can still be found in the environment today.

Exposure

The three main paths of exposure to toxaphene are ingestion, inhalation, and absorption. For humans, the main source of toxaphene exposure is through ingested seafood.[6] When toxaphene enters the body, it usually accumulates in fatty tissues. It is broken down through dechlorination and oxidation in the liver, and the byproducts are eliminated through feces.[6]

People that live near an area that has high toxaphene contamination are at high risk to toxaphene exposure through inhalation of contaminated air or direct skin contact with contaminated soil or water. Eating large quantities of fish on a daily basis also increases susceptibility to toxaphene exposure.[3] Finally, exposure is rare, yet possible through drinking water when contaminated by toxaphene runoff from the soil.[3] However, toxaphene has been rarely seen at high levels in drinking water due to toxaphene's high levels of insolubility in water.[8]

Shellfish, algae, fish and marine mammals have all been shown to exhibit high levels of toxaphene. People in the Canadian Arctic, where a traditional diet consists of fish and marine animals, have been shown to consume ten times the accepted daily intake of toxaphene.[6] Also, blubber from beluga whales in the Arctic were found to have unhealthy and toxic levels of toxaphene.[6]

Health effects

In humans

When inhaled or ingested, sufficient quantities of toxaphene can damage the lungs, nervous system, and kidneys, and may cause death. The major health effects of toxaphene involve central nervous system stimulation leading to convulsive seizures. The dose necessary to induce nonfatal convulsions in humans is about 10 milligrams per kilogram body weight per day.[8] Several deaths linked to toxaphene have been documented in which an unknown quantity of toxaphene was ingested intentionally or accidentally from food contamination. The deaths are attributed to respiratory failure resulting from seizures.[14] Chronic inhalation exposure in humans results in reversible respiratory toxicity.[8]

A study conducted between 1954 and 1972 of male agricultural workers and agronomists exposed to toxaphene and other pesticides showed that there are higher proportions of bronchial carcinoma in the test group than in the unexposed general population. However, toxaphene may not have been the main pesticide responsible for tumor production.[14] Tests on lab animals show that toxaphene causes liver and kidney cancer, so the EPA has classified it as a Group B2 carcinogen, meaning it is a probable human carcinogen. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified it as a Group 2B carcinogen.[8]

Toxaphene can be detected in blood, urine, breast milk, and body tissues if a person has been exposed to high levels, but it is removed from the body quickly, so detection has to occur within several days of exposure.[8]

It is not known whether toxaphene can affect reproduction in humans.[3]

In animals

Toxaphene was used to treat mange in cattle in California in the 1970s and there were reports of cattle deaths following the toxaphene treatment.[15]

Chronic oral exposure in animals affects the liver, the kidney, the spleen, the adrenal and thyroid glands, the central nervous system, and the immune system.[8] Toxaphene stimulates the central nervous system by antagonizing neurons leading to hyperpolarization of neurons and increased neuronal activity.[14]

Regulations

Toxaphene has been found on at least 68 of the 1,699 National Priorities List sites identified by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.[3] Toxaphene has been forbidden in Germany since 1980. Most uses of toxaphene were cancelled in the U.S. in 1982 with the exception of use on livestock in emergency situations, and for controlling insects on banana and pineapple crops in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. All uses of toxaphene were cancelled in the U.S. in 1990.[8]

Toxaphene has been banned in 37 countries, including Austria, Belize, Brazil, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Egypt, the EU, India, Ireland, Kenya, Korea, Mexico, Panama, Singapore, Thailand and Tonga. Its use has been severely restricted in 11 other countries, including Argentina, Columbia, Dominica, Honduras, Nicaragua, Pakistan, South Africa, Turkey, and Venezuela.[16]

In the Stockholm Convention on POPs, which came into effect on 17 May 2004, twelve POPs were listed to be eliminated or their production and use restricted. The OCPs or pesticide-POPs identified on this list have been termed the "dirty dozen" and include aldrin, chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, endrin, heptachlor, hexachlorobenzene, mirex, and toxaphene.[6][17]

The EPA has determined that lifetime exposure to 0.01 milligrams per liter of toxaphene in the drinking water is not expected to cause any adverse noncancer effects if the only source of exposure is drinking water,[3] and has established the maximum contaminant level (MCL) of toxaphene at 0.003 mg/L. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) uses the same level for the maximum level permissible in bottled water.[4]

The FDA has determined that the concentration of toxaphene in bottled drinking water should not exceed 0.003 milligrams per liter.[3]

The United States Department of Transportation lists toxaphene as a hazardous material and has special requirements for marking, labeling, and transporting the material.[4]

It is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities which produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[18]

Trade names

Trade names and synonyms include Chlorinated camphene, Octachlorocamphene, Camphochlor, Agricide Maggot Killer, Alltex, Allotox, Crestoxo, Compound 3956, Estonox, Fasco-Terpene, Geniphene, Hercules 3956, M5055, Melipax, Motox, Penphene, Phenacide, Phenatox, Strobane-T, Toxadust, Toxakil, Vertac 90%, Toxon 63, Attac, Anatox, Royal Brand Bean Tox 82, Cotton Tox MP82, Security Tox-Sol-6, Security Tox-MP cotton spray, Security Motox 63 cotton spray, Agro-Chem Brand Torbidan 28, and Dr Roger's TOXENE.[19]

References

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0113". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Chlorinated camphene". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 4 December 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- "Toxaphene - ToxFAQs". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- "Toxaphene" (PDF). Report on Carcinogens. National Toxicology Program, Department of Health and Human Services. 13. October 2, 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Saleh, Mahmoud Abbas (1983). "Capillary gas chromatography-electron impact chemical ionization mass spectrometry of toxaphene". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 31 (4): 748–751. doi:10.1021/jf00118a017.

- Wen-Tien, Tsai (October 12, 2010). "Current Status and Regulatory Aspects of Pesticides Considered to be Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in Taiwan". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 7 (10): 3615–3627. doi:10.3390/ijerph7103615. PMC 2996183. PMID 21139852.

- "Technical Factsheet on: TOXAPHENE" (PDF). National Primary Drinking Water Regulations. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Toxaphene". Technology Transfer Network - Air Toxics Web Site. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Buntin, G.A. U.S. Patent 2,565,471, 1951.

- Buser HR, Haglund P, Müller MD, Poiger T, Rappe C (2000). "Rapid anaerobic degradation of toxaphene in sewage sludge". Chemosphere. 40 (9–11): 1213–20. Bibcode:2000Chmsp..40.1213B. doi:10.1016/s0045-6535(99)00371-9. PMID 10739064.

- Shoeib M, Brice KA, Hoff RM (August 1999). "Airborne concentrations of toxaphene congeners at Point Petre (Ontario) using gas-chromatography-electron capture negative ion mass spectrometry (GC-ECNIMS)". Chemosphere. 39 (5): 849–71. Bibcode:1999Chmsp..39..849S. doi:10.1016/s0045-6535(99)00018-1. PMID 10448561.

- Rice CP, Samson PJ, Noguchi GE (1986). "Atmospheric transport of toxaphene to Lake Michigan". Environmental Science and Technology. 20 (11): 1109–1116. Bibcode:1986EnST...20.1109R. doi:10.1021/es00153a005.

- "Technical Factsheet on Toxaphene" (PDF). Drinking Water Contaminants. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- "Public Health Goal for TOXAPHENE in Drinking Water" (PDF). California Environmental Protection Agency.

- Chancellor, John; Oliver, Don (1979-02-22). "Possible Toxaphene Cattle Poisoning". NBC News. Vanderbilt Television News Archive. http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/program.pl?ID=502980. Retrieved on 2008-02-08.

- "Toxaphene". Persistent Organic Pollutants Toolkit. Retrieved 2015-04-22.

- http://chm.pops.int/Portals/0/docs/publications/sc_factsheet_004.pdf. Retrieved on 2009-03-05.

- "40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities" (PDF) (July 1, 2008 ed.). Government Printing Office. Retrieved October 29, 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - http://www.epa.gov/safewater/dwh/c-soc/toxaphen.html. Retrieved on 2009-03-05.