Northern Canada

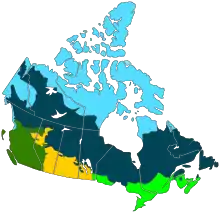

Northern Canada, colloquially the North, is the vast northernmost region of Canada variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut. Similarly, the Far North (when contrasted to the North) may refer to the Canadian Arctic: the portion of Canada that lies north of the Arctic Circle, east of Alaska and west of Greenland. This area covers about 39% of Canada's total land area, but has less than 1% of Canada's population.

Northern Canada

Nord du Canada | |

|---|---|

Northern Canada, defined politically to comprise (from west to east) Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut. | |

| Country | Canada |

| Territories | Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Yukon |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,535,263 km2 (1,364,973 sq mi) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 113,604 |

| • Estimate (2020 Q4)[2] | |

| • Density | 0.032/km2 (0.083/sq mi) |

These reckonings somewhat depend on the arbitrary concept of nordicity, a measure of so-called "northernness" that other Arctic territories share. Canada is the northernmost country in the Americas (excluding the neighbouring Danish Arctic territory of Greenland which extends slightly further north) and roughly 80% of its 38 million[3] residents are concentrated along its southern border with the United States.

Definitions

| Climate | Political | Habitat | Demographic |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Those parts of Northern Canada (dark green areas within the red line) considered to be part of the Arctic Region according to average temperature in the warmest month. | Political definition of Northern Canada – the "territories" of Canada | Barren Grounds and tundra are shown in light blue, and the taiga and boreal forest in dark blue. | The north is divided ethnographically into the Inuit living predominately in the "Arctic" region, First Nations living predominately in the "Subarctic", and Europeans living predominantly in Yukon and urban areas in the Northwest Territories. |

Sub-divisions

As a social rather than political region, the Canadian north is often subdivided into two distinct regions based on climate, the near north and the far north. The different climates of these two regions result in vastly different vegetation, and therefore very different economies, settlement patterns, and histories.

Near north

The "near north" or subarctic is mostly synonymous with the Canadian boreal forest, a large area of evergreen-dominated forests with a subarctic climate. This area has traditionally been home to the Indigenous peoples of the Subarctic, that is the First Nations, who were hunters of moose, freshwater fishers and trappers. This region was heavily involved in the North American fur trade during its peak importance, and is home to many Métis people who originated in that trade. The area was mostly part of Rupert's Land under the nominal control of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) from 1670 to 1869 who regarded Rupert's Land as their proprietary colony.

In 1670, King Charles II of England in his grant creating the proprietary colony Rupert's Land defined its frontiers as all the lands adjudging Hudson Strait, Hudson Bay or rivers flowing into Hudson Bay, in theory giving control of much of what is now Canada to the HBC.[4] Under the royal charter of 2 May 1670, the HBC received the theoretical control of 1.5 million square miles making up 40% of what is now Canada.[5] Despite its claim that Rupert's Land was a proprietary colony, the HBC only controlled the areas around its forts (trading post) on the shores of James Bay and Hudson Bay, and never sought to impose political control on the First Nations peoples, whose co-operation was needed for the fur trade. For its first century, the HBC never ventured inland, being content to have the First Nations peoples come to its forts to trade fur for European goods.[6] The HBC only started to move inland in the late 18th century to assert its claim to Rupert's Land in response to rival fur traders coming out of Montreal who were hurting profits by going directly to the First Nations.[7]

The HBC's claim to Rupert's Land, which, as the company was the de facto administrator, included the North-Western Territory, was purchased by the Canadian government in 1869.[8] After buying Rupert's Land, Canada renamed the area it had purchased the Northwest Territories. Shortly thereafter the government made a series of treaties with the local First Nations regarding land title. This opened the region to non-Native settlement, as well as to forestry, mining, and oil and gas drilling. In 1896, gold was discovered in the Yukon, leading to the Klondike Gold Rush in 1896-1899 and the first substantial white settlements were made in the near north. To deal with the increased settlement in the Klondike, the Yukon Territory was created in 1898.

Today several million people live in the near north, around 15% of the Canadian total. Large parts of the near north are not part of Canada's territories, but rather are the northern parts of the provinces of Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, meaning they have very different political histories as minority regions within larger units. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Canada reduced the size of the Northwest Territory by carving out new provinces out of it such as Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba together with the new territory of the Yukon while transferring other parts of the Northwest Territory to Ontario and Quebec.

Far north

The "far north" is synonymous with the areas north of the tree line: the Barren Grounds and tundra. This area is home to the various sub-groups of the Inuit, a people unrelated to other Indigenous peoples in Canada. These are people who have traditionally relied mostly on hunting marine mammals and caribou, mainly barren-ground caribou, as well as fish and migratory birds. The Inuit lived in groups that pursued a hunter-gather lifestyle and had nothing that resembled a government with power being exercised by the local headman, a person acknowledged to be the best hunter,[9] and the angakkuq, sometimes called shamans.[10] This area was somewhat involved in the fur trade, but was more influenced by the whaling industry.[11] Britain maintained a claim to the far north as part of the British Arctic Territories, and in 1880 transferred its claim to Canada, who included in far north into the Northwest Territories.[11]

The Inuit were not aware of the existence of the British Arctic territory claim nor were they aware for some time afterwards that under international law their territories had just been included in Canada.[12] It was not until 1920 when detachments of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) started being sent into the far north to enforce Canadian law that Canadian sovereignty over the region became effective.[13] This area was not part of the early 20th century treaty process and aboriginal title to the land has been acknowledged by the Canadian government with the creation of autonomous territories instead of the Indian reserves of further south.

In 1982 a referendum was held to decide on splitting the Northwest Territories. This was followed by the 1992 Nunavut creation referendum with the majority of the people in far north voting to leave the Northwest Territories, leading to the new territory of Nunavut being created in 1999. Very few non-Indigenous people have settled in these areas, and the residents of the far north represent less than 1% of Canada's total population.

The far north is also often broken into the west and eastern parts and sometimes a central part. The eastern Arctic which means the self-governing territory of Nunavut (much of which is in the true Arctic, being north of the Arctic Circle), sometimes excluding Cambridge Bay and Kugluktuk; Nunavik, an autonomous part of the province of Quebec; Nunatsiavut, an autonomous part of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador; and perhaps a few parts of the Hudson Bay coast of Ontario and Manitoba. The western Arctic is the northernmost portion of the Northwest Territories (roughly Inuvik Region) and a small part of Yukon, together called the Inuvialuit Settlement Region and sometimes includes Cambridge Bay and Kugluktuk. The central Arctic covers the pre-division Kitikmeot Region, Northwest Territories.

| Flag | Arms | Territory | Capital | Area | Population (2016)[14] | Population density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Northwest Territories | Yellowknife | 1,346,106 km2 (519,734 sq mi) | 41,786 | 0.031 per square kilometre (0.080/sq mi) |

|

|

Nunavut | Iqaluit | 2,038,722 km2 (787,155 sq mi) | 35,944 | 0.017 per square kilometre (0.044/sq mi) |

|

|

Yukon | Whitehorse | 482,443 km2 (186,272 sq mi) | 35,874 | 0.074 per square kilometre (0.19/sq mi) |

Territoriality

Since 1925, Canada has claimed the portion of the Arctic between 60°W and 141°W longitude, extending all the way north to the North Pole: all islands in the Arctic Archipelago and Herschel, off the Yukon coast, form part of the region, are Canadian territory and the territorial waters claimed by Canada surround these islands.[15] Views of territorial claims in this region are complicated by disagreements on legal principles. Canada and the Soviet Union/Russia have long claimed that their territory extends according to the sector principle to the North Pole. The United States does not accept the sector principle and does not make a sector claim based on its Alaskan Arctic coast. Claims that undersea geographic features are extensions of a country's continental shelf are also used to support claims; for example the Denmark/Greenland claim on territory to the North Pole, some of which is disputed by Canada. Foreign ships, both civilian and military, are allowed the right of innocent passage through the territorial waters of a littoral state subject to conditions in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.[16] The right of innocent passage is not allowed, however, in internal waters, which are enclosed bodies of water or waters landward of a chain of islands. Disagreements about the sector principle or extension of territory to the North Pole and about the definition of internal waters in the Arctic lie behind differences in territorial claims in the Arctic. This claim is recognized by most countries with some exceptions, including the United States; Denmark, Russia, and Norway have made claims similar to those of Canada in the Arctic and are opposed by the European Union and the United States. This is especially important with the Northwest Passage. Canada asserts control of this passage as part of the Canadian Internal Waters because it is within 20 km (12 mi) of Canadian islands; the United States claims that it is in international waters. Today ice and freezing temperatures make this a minor issue, but climate change may make the passage more accessible to shipping, something that concerns the Canadian government and inhabitants of the environmentally sensitive region.[17]

Similarly, the disputed Hans Island (with Denmark), in the Nares Strait, which is west of Greenland, may be an indication of challenges to overall Canadian sovereignty in the North.

Topography (geography)

While the largest part of the Arctic is composed of permanent ice and the Canadian Arctic tundra north of the tree line, it encompasses geological regions of varying types: the Innuitian Mountains, associated with the Arctic Cordillera mountain system, are geologically distinct from the Arctic Region (which consists largely of lowlands). The Arctic and Hudson Bay Lowlands comprise a substantial part of the geographic region often considered part of the Canadian Shield (in contrast to the sole geological area). The ground in the Arctic is mostly composed of permafrost, making construction difficult and often hazardous, and agriculture virtually impossible.

The Arctic watershed (or drainage basin) drains northern parts of Manitoba, Alberta and British Columbia, most of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut as well as parts of Yukon into the Arctic Ocean, including the Beaufort Sea and Baffin Bay. With the exception of the Mackenzie River, Canada's longest river, this watershed has been little used for hydroelectricity. The Peace and Athabasca rivers along with Great Bear and Great Slave Lake (respectively the largest and second largest lakes wholly enclosed within Canada), are significant elements of the Arctic watershed. Each of these elements eventually merges with the Mackenzie so that it thereby drains the vast majority of the Arctic watershed.

Climate

Overview

Under the Köppen climate classification, much of Northern Canada has a subarctic climate, with a tundra climate in most of the Arctic Archipelago and an Ice cap climate in the Arctic Cordillera.[18][19] For more than half of the year, much of Northern Canada is snow and ice-covered, with some limited moderation by the relatively warmer waters in coastal areas with temperatures generally remaining below the freezing mark from October to May.[19] During the coldest three months, mean monthly temperatures range from −29 °C (−20 °F) in the southern sections to −34 °C (−30 °F) in the northern sections although temperatures can go down to −48 to −51 °C (−55 to −60 °F).[19] Owing to the dry cold air prevalent throughout most of the region, snowfall is often light in nature.[19] During the short summers, much of Northern Canada is snow free, except for the Arctic Cordillera which remains covered with snow and ice throughout the year.[19] In the summer months, temperatures average below 7 °C (45 °F) and may occasionally exceed 18 °C (65 °F).[19] Most of the rainfall accumulated occurs in the summer months, ranging from 25 to 51 mm (1 to 2 in) in the northernmost islands to 180 mm (7 in) at the southern end of Baffin Island.[19]

Demographics

Using the political definition of the three northern territories, the North, with an area of 3,921,739 km2 (1,514,192 sq mi), makes up 39.3% of Canada.[20]

Although vast, the entire region is very sparsely populated. As of 2016, only about 113,604 people lived there compared to 35,151,728 in the rest of Canada.[14]

The population density for Northern Canada is 0.03 inhabitants per square kilometre (0.078/sq mi) (0.07/km2 (0.18/sq mi) for Yukon, 0.04/km2 (0.10/sq mi) for the NWT and 0.02/km2 (0.052/sq mi) for Nunavut) compared to 3.7/km2 (9.6/sq mi) for Canada.[21]

It is heavily endowed with natural resources and in most cases they are very expensive to extract and situated in fragile environmental areas. Though GDP per person is higher than elsewhere in Canada, the region remains relatively poor, mostly because of the extremely high cost of most consumer goods, and the region is heavily subsidised by the government of Canada.

As of 2016, 53.3% of the population of the three territories (23.3% in Yukon,[22] 50.7% in the NWT[22] and 85.9% in Nunavut[22]) is Indigenous, Inuit, First Nations or Métis. The Inuit are the largest group of Indigenous peoples in Northern Canada, and 53.0% of all Canada's Inuit live in Northern Canada, with Nunavut accounting for 46.4%.[22] The region also contains several groups of First Nations, who are mainly Dene with the Chipewyan making up the largest sub-group. The three territories each have a greater proportion of Aboriginal inhabitants than any of Canada's provinces. There are also many more recent immigrants from around the world; of the territories, Yukon has the largest percentage of non-Aboriginal inhabitants, while Nunavut the smallest.[22]

As of 2016 census, the largest settlement in Northern Canada is the capital of Yukon, Whitehorse with 25,085.[23] Second is Yellowknife, the capital of the Northwest Territories, which contains 19,569 inhabitants.[24] Third is Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut, with 7,082.[25]

Recent

Although it has not been on the same scale, some towns and cities have experienced population increases not seen for several decades before. Yellowknife has become the centre of diamond production for Canada (which has become one of the top three countries for diamonds).

In the 2006 Canadian Census, the three territories posted a combined population of over 100,000 people for the first time in Canadian history.[21]

See also

References

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data". Statistics Canada. 2017-02-08. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- "Population by year of Canada of Canada and territories". Statistics Canada. September 26, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- "Population by year of Canada of Canada and territories". Statistics Canada. October 6, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- Newman, Peter Empire of the Bay, London: Penguin, 1989 p.78-79.

- Dolin, Eric Jay Fur, Fortune, and Empire: The Epic History of the Fur Trade in America, New York: W.W. Norton, 2011 p.102

- Newman, Peter Empire of the Bay, London: Penguin, 1989 p.167-168.

- Newman, Peter Empire of the Bay, London: Penguin, 1989 p.252.

- Newman, Peter Empire of the Bay, London: Penguin, 1989 p.575-576.

- Law-Ways of the Primitive Eskimos, page 667

- Matthiasson, John S. Living on the Land Change Among the Inuit of Baffin Island Toronto: University of Toronto Press p.118-119

- Matthiasson, John S. Living on the Land Change Among the Inuit of Baffin Island Toronto: University of Toronto Press p.27

- Matthiasson, John S. Living on the Land Change Among the Inuit of Baffin Island Toronto: University of Toronto Press p.27-28

- Matthiasson, John S. Living on the Land Change Among the Inuit of Baffin Island Toronto: University of Toronto Press p.41-42

- "Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables, 2016 Census – Canada, provinces and territories". 2016 Census. Statistics Canada.

- "Territorial Evolution, 1927". March 18, 2009. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012.

- "GlobeLaw.com". www.globelaw.com.

- Paikin, Zach. "Canada: The Arctic Middle Man" Maritime Executive, 21 August 2014. Accessed: 11 September 2014.

- Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- Canada Year Book 1967, p. 57.

- "Land and freshwater area, by province and territory". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. 1 February 2005. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, 2011 and 2006 censuses". www12.statcan.gc.ca.

- "Aboriginal Peoples Highlight Tables, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. Government of Canada. 27 August 2020.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census: Whitehorse, City [Census subdivision], Yukon and Yukon [Territory]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. February 15, 2019.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census: Yellowknife, City [Census subdivision], Northwest Territories and Yellowknife [Population centre], Northwest Territories". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. 15 February 2019.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census: Iqaluit [Population centre], Nunavut and Baffin, Region [Census division], Nunavut". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. 15 February 2019.

Further reading

- Honderich, John. Arctic Imperative: Is Canada Losing the North? Toronto, Ont.: University of Toronto Press, 1987. xi, 258 p., ill. in b&w with charts, maps, and photos. ISBN 0-8020-5763-2

- Mowat, Farley. Canada North, in series, The Canadian Illustrated Library. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1967. 127, [1] p., copiously ill. in b&w and col.

- Canada Year Book 1967 (PDF). Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada. 1967. pp. 57–63. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Northern Canada. |

| Look up Northern Canada in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Northern Canada travel guide from Wikivoyage

Northern Canada travel guide from Wikivoyage- The Papers of Herbert R. Drury on Arctic Canada at Dartmouth College Library

- Gerard Gardner Scientific Observations Records in Arctic Canada and Labrador at Dartmouth College Library