Tuberculosis in India

Tuberculosis in India is includes all experience, culture, and health response which India has with the disease tuberculosis. Tuberculosis in India is a major health problem causing about 220,000 deaths every year. The cost of the death and disease in the Indian economy between 2006 and 2014 was approximately USD 1 billion.[1]

Despite the historical challenges, the technology and health care for treating tuberculosis have improved. In 2020 the Indian government made bold statements to eliminate TB from the country by 2025 through its National TB Elimination Program. Interventions in this program include major investment in health care, providing supplemental nutrition credit through the Nikshay Poshan Yojana, organizing a national epidemiological survey for tuberculosis, and organizing a national campaign to tie together the Indian government and private health infrastructure for the goal of eliminating TB.

India bears a disproportionately large burden of the world's tuberculosis rates, as it continues to be the biggest health problem in India. India is the highest TB burden country with World Health Organization (WHO) statistics for 2011 giving an estimated incidence figure of 2.2 million cases of TB for India out of a global incidence of 9.6 million cases.[2]

Tuberculosis is India's biggest health issue, but what makes this issue worse is the recently discovered phenomenon of TDR-TB - Totally Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. This issue of drug-resistant TB began with MDR-TB, and moved on to XDR-TB. Gradually, the most dangerous form has situated itself in India as TDR-TB.

Epidemiology

Tuberculosis is one of India's major public health problems. According to WHO estimates, India has the world's largest tuberculosis epidemic.[3] Many research studies have shown the effects and concerns revolving around TDR-TB, especially in India; where social and economic positions are still in progression. In Zarir Udwadia’s report originated from the Hinduja Hospital in Mumbai, India explicitly discusses the drug-resistant effects and results.[4] An experiment was conducted in January, 2012 on four patients to test how accurate the “new category” of TDR-TB is. These patients were given all the first-line drugs and second-line drugs that usually are prescribed to treat TB, and as a result, were resistant to all. As a response, the government of India had stayed in denial, but WHO took it as a more serious matter and decided that although the patterns of drug-resistance were evident, they cannot rely on just that to create a new category of TDR-TB.

Compared to India, Canada has about 1,600 new cases of TB every year.[5] Citing studies of TB-drug sales, the government now suggests the total went from being 2.2 million to 2.6 million people nationwide.[6] On March 24, 2019, TB Day, the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare of India notified that 2.15 million new tuberculosis patients has discovered only in 2018.[7]

In India, TB is responsible for the death of every third AIDS patient. moreover, India accounts for about a quarter of the Global TB Burden.[7] The ministry reiterated their commitment to eliminating TB in the country by 2025.[7] As part of its efforts to eliminate Tuberculosis, the Union government changed the name of Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program (RNTCP) to National Tuberculosis Elimination Program (NTEP) on December 30, 2019.[8]

Symptoms

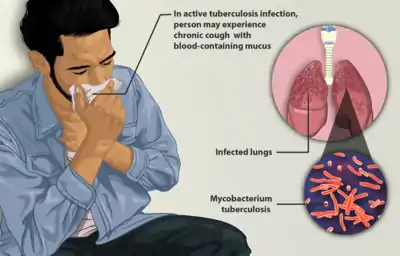

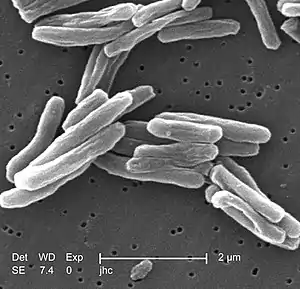

The bacterium that causes TB is called Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Inactive tuberculosis means that one can even unconsciously and unknowingly acquire the bacteria for tuberculosis within them but not even know about it because it is inactive. Whereas, active tuberculosis is the start of the bacteria developing, and the signs and symptoms begin to be visible. This is when tuberculosis is active within you, and is a serious issue leading to even more serious results. Although the TB bacteria can infect any organ (e.g., kidney, lymph nodes, bones, joints) in the body, the disease commonly occurs in the lungs.[5] Around 80% of all TB cases are related to pulmonary or lung.

Common symptoms include: coughing (that lasts longer than 3 weeks with green, yellow, or bloody sputum), weight loss, fatigue, fever, night sweats, chills, chest pain, shortness of breath, and loss of appetite.

Causes

There is a specific bacterium that evolves inside the body to result in tuberculosis, known as mycobacterium tuberculosis. This bacterium is only spread throughout the body when a person has an active TB infection. One of many causes of acquiring TB is living a life with a weak immune system; everything becomes fragile, and an easy target. That is why babies, children, and senior adults have a higher risk of adapting TB.[5] The bacterium spreads in the air sacs, and passes off into the lungs, resulting in an infected immune system.

In addition, coughing, sneezing, and even talking to someone can release the mycobacterium into the air, consequently affecting the people breathing this air. It has been stated that your chances of becoming infected are higher if you come from – or travel to – certain countries where TB is common, and where there is a big proportion of homeless people.[5] India, having the most TB cases of any country[9] falls under this cause because it stands recognized as consuming a higher chance of gaining TB.

Socioeconomic Dimensions of TB

Those listed are all the bodily and personal causes of acquiring TB, but decreases in tuberculosis in India incidence are correlated with improvements in social and economic determinants of health moreso than with access to quality treatment.[10] In India, TB occurs at high rates because of the pollution dispersed throughout the country. Pollution causes many effects in the air the people breathe there, and since TB can be gained through air, the chances of TB remain high and in a consistent movement going uphill for India.

Lack of infrastructure

Another major cause for the growth of TB in India has to do with it currently still standing as a developing country. Because its economy is still developing, the citizens are still fighting for their rights, and the structure of the country lies in poor evidence that it is not fit as other countries still. A study of Delhi slums has correlated higher scores on the Human Development Index and high proportions of one-room dwellings tended to incur TB at higher rates.[11] Poor built environments, including hazards in the workplace, poor ventilation, and overcrowded homes have also been found to increase exposure to TB [10]

Access to treatment

TB rises high in India because of the majority of patients are not able to afford the treatment drugs prescribed. “At present, only the 1.5 million patients already under the Indian government's care get free treatments for regular TB. That leaves patients who seek treatment in India's growing private sector to buy drugs for themselves, and most struggle to do that, government officials say.”[6] Although the latest phase of state-run tuberculosis eradication program, the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program, has focused on increasing access to TB care for poor people,[9] the majority of poor people still cannot access TB care financially.[12]

Consequently, high priced treatment drugs and the struggles of “poor patients” also brawl through the poor treatment they receive in response to acquiring TB. “It is estimated that just 16% of patients with drug-resistant TB are receiving appropriate treatment”.[13] To combat this huge problem, India has instated a new program to try to provide free drugs to all those infected in the country.[6]

While RNTCP has created schemes to offer free or subsidized, high quality TB care, less than 1% of private practitioners have taken up these practices.[12] Lastly, as high pricing is linked to the economic standings of India, which is linked to poor treatment, it all underlines the lack of education and background information practitioners and professionals hold for prescribing drugs, or those private therapy sessions. A study conducted in Mumbai by Udwadia, Amale, Ajbani, and Rodrigues, showed that only 5 of 106 private practitioners practicing in a crowded area called Dharavi could prescribe a correct prescription for a hypothetical patient with MDR tuberculosis.[14] Because the majority of TB cases are addressed by private providers, and because the majority of poor people access informal (private) providers, the RNTCP's goals for universal access to TB care have not been met.[12]

Poor health

Poverty and lacking financial resources are also associated with malnutrition, poor housing conditions, substance use, and HIV/AIDS incidence. These factors often cause immunosuppression, and are accordingly correlated with higher susceptibility to TB;[10] they also tend to have greater impacts on people from high incidence countries such as India than lower incidence countries.[15] Indeed, addressing these factors may have a stronger correlation with decreased TB incidence than the decreasing financial burdens associated with care.[10] Yet, the RNTCP's treatment protocols do not address these social determinants of health.[10]

Treatment

Treatment in India is on the rise just as the disease itself is on the rise. To prevent spreading TB, it's important to get treatment quickly and to follow it through to completion by your doctor. This can stop transmission of the bacteria and the appearance of antibiotic-resistant strains. It is a known fact that bacterial infections require antibiotics for treatment and prevention, thus, commonly you will see that patients diagnosed with tuberculosis have certain pills and antibiotics carried around with them. The antibiotics most commonly used include isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. It is crucial to take your medication as instructed by your doctor, and for the full course of the treatment (months or years). This helps to ward off types of TB bacteria that are antibiotic-resistant, which take longer and are more difficult to treat.[5] In India’s case, the particular type of TB infections are majority resistant to regular antibiotic treatment (MDR-TB, XDR-TB, TDR-TB), therefore, not one or two medications will help, rather a combination of different medications must be taken for over a course of 18–24 months, depending on how deep the infection is. Since the 1960s, two drugs — isoniazid and rifampicin — have been the standard TB treatment.[13] In addition to antibiotics, a vaccine is available to limit the spread of bacteria after TB infection. The vaccine is generally used in countries or communities where the risk of TB infection is greater than 1% each year,[5] thus, the country of India; whose TB infection rate is at a peak (world’s third highest TB infected country), and is consistently growing, and giving 20% of the world’s diagnosed patients a home.[13] At present the anti TB treatment offered in public and private sector in India is not satisfactory and needs to be improved. Today India's TB control program needs to update itself with the international TB guidelines as well as provide an optimal anti TB treatment to the patients enrolled under it or it will land up being another factor in the genesis of drug-resistant tuberculosis.[16]

History

India's response to TB has changed with time and technology.[17] One way to divide responses to TB are the activities from the time from pre-independence, post-independence and current WHO-assisted period.[17]

After Independence

After Independence the Indian government established various regional and national TB reduction programmes.[17]

Global participation

The contemporary response to TB includes India's participation and leadership in global TB reduction and elimination programs.[17]

The Indian government’s Revised National TB Control Programme (RNTCP) started in India during 1997. The program uses the WHO-recommended Directly Observed Treatment Short Course (DOTS) strategy to develop ideas and data on TB treatment. This group’s initial objective is to achieve and maintain a TB treatment success rate of at least 85% in India among new patients.[18] “In 2010 the RNTCP made a major policy decision that it would change focus and adopt the concept of Universal Access to quality diagnosis and TB treatment for all TB patients”.[19] By doing so, they extend out a helping hand to all people diagnosed with TB, and in addition, provide better quality services and improve on therapy for these patients.

Treatment recommendations from Udwadia, et al. suggest that patients with TDR-TB only be treated “within the confines of government-sanctioned DOTS-Plus Programs to prevent the emergence of this untreatable form of tuberculosis”.[13] As this confirming result of hypothesis is at a conclusion by Udawadai, et al., it is given that the new Indian government program will insist on providing drugs free of charge to TB patients of India, for the first time ever.[6]

Society and culture

Organizations

The Tuberculosis Association of India is a voluntary organization. It was set up in February 1939. It is also affiliated to the Govt. of India & is working with TB Delhi center.[20]

The Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program (RNTCP) has established a network of laboratories where TB tests can be done to diagnose people who have TB. There are also tests that can be done to determine whether a person has drug-resistant TB.

The laboratory system comprises National Reference Laboratories (NRLs), state level Intermediate Reference Laboratories (IRLs), Culture & Drug Susceptibility Testing (C & DST) laboratories and Designated Microscopy Centres (DMCs). Some of Private lab also Accredited for Culture & Drug Susceptibility Testing for M.tuberculosis (i.e Microcare Laboratory & tuberculosis Research Centre, Surat)

Stigma

Disempowerment and stigma are often felt by TB patients as they are disproportionately impoverished or socially marginalized.[21] The DOTS treatment regimen of the RNTCP is thought to deepen this sentiment,[22] as its close monitoring of patients can decrease patient autonomy. To counteract disempowerment, some countries have engaged patients in the process of implementing the DOTS and in creating other treatment regimens that adhere to their nonclinical needs. Their knowledge can inform valuable complements[23] the clinical care provided by the DOTS. Pro-poor strategies, including wage compensation for time lost to treatment, working with civil society organizations to link low income patients to social services, nutritional support, and offering local NGOs and committees a platform for engagement with the work done by private providers may reduce the burden of TB[24] and leads to greater patient autonomy.

Economics

Some legal advocates have argued that public interest litigation in India must be part of the TB response strategy to ensure that available resources actually fund the necessary health response.[25]

India has a large burden of the world's TB, with an estimated economic loss of US $43 billion and 100 million lost annually directly due to this disease.[26]

Special populations

The most certain knowledge about how Scheduled Tribes and other Adivasi experience TB is that there is a lack of research and understanding of the health of this demographic.[27][28] There is recognition that this community is more vulnerable and has less access to treatment, but details are lacking on how TB affects tribal communities.[27][28]

References

- World Health Organization (2009). "Epidemiology". Global tuberculosis control: epidemiology, strategy, financing. pp. 6–33. ISBN 978-92-4-156380-2. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- TB Statistics for India. (2012). TB Facts. Retrieved April 3, 2013, from http://www.tbfacts.org/tb-statistics-india.html

- WHO. Global tuberculosis control. WHO report. WHO/HTM/TB/2006.362. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006.

- Udwadia, Zarir; Vendoti, Deepesh (2013). "Totally drug-resistant tuberculosis (TDR-TB) in India: Every dark cloud has a silver lining". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 67 (6): 471–472. doi:10.1136/jech-2012-201640. PMID 23155059. S2CID 42481569.

- Tuberculosis - Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, Diagnosis. (2013). C-Health. Retrieved April 3, 2103, from http://chealth.canoe.ca/channel_condition_info_details.asp?disease_id=231&channel_id=1020&relation_id=71085

- Anand, Geeta; McKay, Betsy (26 December 2012). "Awakening to Crisis, India Plans New Push Against TB". Wall Street Journal.

- "India records 2.15m new TB patients in 2018". The Nation. 2019-03-26. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- AuthorTelanganaToday. "TB eradication mission renamed". Telangana Today. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- Sachdeva, Kuldeep Singh et al. “New vision for Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP): Universal access - "reaching the un-reached".” The Indian journal of medical research vol. 135,5 (2012): 690-4.

- Hargreaves, James R.; Boccia, Delia; Evans, Carlton A.; Adato, Michelle; Petticrew, Mark; Porter, John D. H. (April 2011). "The Social Determinants of Tuberculosis: From Evidence to Action". American Journal of Public Health. 101 (4): 654–662. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.199505. PMC 3052350. PMID 21330583.

- Chandra, Shivani; Sharma, Nandini; Joshi, Kulanand; Aggarwal, Nishi; Kannan, Anjur Tupil (17 January 2014). "Resurrecting social infrastructure as a determinant of urban tuberculosis control in Delhi, India". Health Research Policy and Systems. 12 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1478-4505-12-3. PMC 3898563. PMID 24438431.

- Verma, Ramesh; Khanna, Pardeep; Mehta, Bharti (2013). "Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program in India: The Need to Strengthen". International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 4 (1): 1–5. PMC 3570899. PMID 23413398.

- Rowland, Katherine (2012). "Totally drug-resistant TB emerges in India". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.9797. S2CID 84692169.

- Udwadia, Z. F; Amale, R. A; Ajbani, K. K; Rodrigues, C (2011). "Totally Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in India". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 54 (4): 579–581. doi:10.1093/cid/cir889. PMID 22190562.

- Dye, Christopher; Bourdin Trunz, Bernadette; Lönnroth, Knut; Roglic, Gojka; Williams, Brian G.; Gagneux, Sebastien (21 June 2011). "Nutrition, Diabetes and Tuberculosis in the Epidemiological Transition". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): e21161. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621161D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021161. PMC 3119681. PMID 21712992.

- Mishra, Gyanshankar; Ghorpade, S. V; Mulani, J (2014). "XDR-TB: An outcome of programmatic management of TB in India". Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. 11 (1): 47–52. doi:10.20529/IJME.2014.013. PMID 24509111.

- Sandhu, GK (April 2011). "Tuberculosis: current situation, challenges and overview of its control programs in India". Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 3 (2): 143–50. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.81691. PMC 3125027. PMID 21731301.

- http://www.scidev.net/tb/facts%5B%5D%5B%5D%5B%5D

- Coghaln, Andy (12 January 2012). "Totally drug-resistant TB at large in India". New Scientist.

- "Welcome to the Tuberculosis Association of India".

- Daftary, Amrita; Frick, Mike; Venkatesan, Nandita; Pai, Madhukar (31 October 2017). "Fighting TB stigma: we need to apply lessons learnt from HIV activism". BMJ Global Health. 2 (4): e000515. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000515. PMC 5717927. PMID 29225954.

- Achmat, Z (December 2006). "Science and social justice: the lessons of HIV/AIDS activism in the struggle to eradicate tuberculosis". The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 10 (12): 1312–7. PMID 17167946.

- "Street Science: Characterizing Local Knowledge". Street Science. 2005. doi:10.7551/mitpress/6494.003.0004. ISBN 978-0-262-27080-9.

- Kamineni, Vishnu VARDHAN; Wilson, Nevin; Das, Anand; Satyanarayana, Srinath; Chadha, Sarabjit; Singh Sachdeva, Kuldeep; Singh Chauhan, Lakbir (2012). "Addressing poverty through disease control programmes: examples from Tuberculosis control in India". International Journal for Equity in Health. 11 (1): 17. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-11-17. PMC 3324374. PMID 22449205.

- McBroom, K (June 2016). "Litigation as TB Rights Advocacy: A New Delhi Case Study". Health and Human Rights. 18 (1): 69–84. PMC 5070681. PMID 27781000.

- Udwadia, Zarir F (2012). "MDR, XDR, TDR tuberculosis: Ominous progression". Thorax. 67 (4): 286–288. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201663. PMID 22427352.

- Rao, VG; Muniyandi, M; Bhat, J; Yadav, R; Sharma, R (January 2018). "Research on tuberculosis in tribal areas in India: A systematic review". The Indian Journal of Tuberculosis. 65 (1): 8–14. doi:10.1016/j.ijtb.2017.06.001. PMID 29332655.

- Thomas, BE; Adinarayanan, S; Manogaran, C; Swaminathan, S (May 2015). "Pulmonary tuberculosis among tribals in India: A systematic review & meta-analysis". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 141 (5): 614–23. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.159545 (inactive 2021-01-13). PMC 4510760. PMID 26139779.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

Further consideration

- Central TB Division (March 2020). "India TB Report 2020". tbcindia.gov.in. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

- WHO Stop TB Department (2010). "A Brief History of Tuberculosis Control in India". World Health Organization.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tuberculosis in India. |

- Central Tuberculosis Division of the Government of India