Religious violence in India

Religious violence in India includes acts of violence by followers of one religious group against followers and institutions of another religious group, often in the form of rioting.[1] Religious violence in India has generally involved Hindus and Muslims.[2]

Despite the secular and religiously tolerant constitution of India, broad religious representation in various aspects of society including the government, the active role played by autonomous bodies such as National Human Rights Commission of India and National Commission for Minorities, and the ground-level work being done by non-governmental organisations, sporadic and sometimes serious acts of religious violence tend to occur as the root causes of religious violence often run deep in history, religious activities, and politics of India.[3][4][5][6]

Along with domestic organizations, international human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch publish reports[7] on acts of religious violence in India. From 2005 to 2009, an average of 130 people died every year from communal violence, or about 0.01 deaths per 100,000 population. The state of Maharashtra reported the highest total number of religious violence related fatalities over that five-year period, while Madhya Pradesh experienced the highest fatality rate per year per 100,000 population between 2005 and 2009.[8] Over 2012, a total of 97 people died across India from various riots related to religious violence.[9]

The US Commission on International Religious Freedom classified India as Tier-2 in persecuting religious minorities, the same as that of Iraq and Egypt. In a 2018 report, USCIRF charged Hindu nationalist groups for their campaign to "Saffronize" India through violence, intimidation, and harassment against non-Hindus, Dalits (untouchable outcastes)& Adivasis (indigenous tribes and nomads).[10] Approximately one-third of state governments enforced anti-conversion and/or anti-cow slaughter[11] laws against non-Hindus, and mobs engaged in violence against Muslims or Dalits whose families have been engaged in the dairy, leather, or beef trades for generations, and against Christians for proselytizing. "Cow protection" lynch mobs killed at least 10 victims in 2017.[10][12][13]

Many historians argue that religious violence in independent India is a legacy of the British policy of divide and rule during the colonial era, in which administrators pitted Hindus and Muslims against one another, a tactic that eventually culminated in the partition of India.[14]

Ancient India

Ancient text Ashokavadana, a part of the Divyavadana, mention a non-Buddhist in Pundravardhana drew a picture showing the Buddha bowing at the feet of Nirgrantha Jnatiputra (identified with Mahavira, 24th tirthankara of Jainism). On complaint from a Buddhist devotee, Ashoka, an emperor of the Maurya Dynasty, issued an order to arrest him, and subsequently, another order to kill all the Ajivikas in Pundravardhana. Around 18,000 followers of the Ajivika sect were executed as a result of this order.[15] Sometime later, another Nirgrantha follower in Pataliputra drew a similar picture. Ashoka burnt him and his entire family alive in their house.[16] He also announced an award of one dinara (silver coin) for the head of a Nirgrantha. According to Ashokavadana, as a result of this order, his own brother, Vitashoka, was mistaken for a heretic and killed by a cowherd. Their ministers advised that "this is an example of the suffering that is being inflicted even on those who are free from desire" and that he "should guarantee the security of all beings". After this, Ashoka stopped giving orders for executions.[15] According to K. T. S. Sarao and Benimadhab Barua, stories of persecutions of rival sects by Ashoka appear to be a clear fabrication arising out of sectarian propaganda.[16][17][18]

The Divyavadana (divine stories), an anthology of Buddhist mythical tales on morals and ethics, many using talking birds and animals, was written in about 2nd century AD. In one of the stories, the razing of stupas and viharas is mentioned with Pushyamitra. This has been historically mapped to the reign of King Pushyamitra of the Shunga Empire about 400 years before Divyavadana was written. Archeological remains of stupas have been found in Deorkothar that suggest deliberate destruction, conjectured to be one mentioned in Divyavadana about Pushyamitra.[19] It is unclear when the Deorkothar stupas were destroyed, and by whom. The fictional tales of Divyavadana is considered by scholars[20] as being of doubtful value as a historical record. Moriz Winternitz, for example, stated, "these legends [in the Divyāvadāna] scarcely contain anything of much historical value".[20]

Medieval India

Historical records of religious violence are extensive for medieval India, in the form of corpus written by Muslim historians. According to Will Durant, Hindus historically experienced persecution during Islamic rule of the Indian subcontinent.[21] There are also numerous recorded instances of temple desecration, by Hindu, Muslim and Buddhist kingdoms, desecrating Hindu, Buddhist and Jain temples.[22][23]

Will Durant calls the Muslim conquest of India "probably the bloodiest story in history".[24] During this period, Buddhism declined rapidly while Hinduism faced military-led and Sultanates-sponsored religious violence.[24] Even those Hindus who converted to Islam were not immune from persecution, which was illustrated by the Muslim caste system in India as established by Ziauddin Barani in the Fatawa-i Jahandari.[25] While Alain Danielou writes that, "From the time Muslims started arriving in 632 A.D., the history of India becomes a long monotonous series of murders, massacres, spoliations, destructions."[26]

Sociologist G. S. Ghurye writes that religious violence between Hindus and Muslims in medieval India may be presumed to have begun soon after Muslims began settling there.[27] Recurrent clashes appear in the historical record during the Delhi Sultanate. They continued through the Mughal Empire, and then in the British colonial period.[28]

During the British period, religious affiliation became an issue ... Religious communities tended to become political constituencies. This was particularly true of the Muslim League created in 1905, which catered exclusively for the interests of the Muslims ... Purely Hindu organizations also appeared such as the Hindu Sabha (later Mahasabha) founded in 1915. In the meantime Hindu-Muslim riots became more frequent; but they were not a novelty: they are attested since the Delhi sultanate and were already a regular feature of the Mughal Empire ... When in 1947 he [Muhammad Ali Jinnah] became the first Governor General of Pakistan and the new border was demarcated, gigantic riots broke out between Hindus and Muslims.

Religious violence was also witnessed during the Portuguese rule of Goa that began in 1560.[29]

Hindu, Buddhist and Jain kingdoms (642–1520)

In early medieval India, there were numerous recorded instances of temple desecration by Indian kings against rival Indian kingdoms, involving conflict between devotees of different Hindu deities, as well as between Hindus, Buddhists and Jains.[22][23][30] In 642, the Pallava king Narasimhavarman I looted a Ganesha temple in the Chalukyan capital of Vatapi. Circa 692, Chalukya armies invaded northern India where they looted temples of Ganga and Yamuna. In the 8th century, Bengali troops from the Buddhist Pala Empire desecrated temples of Vishnu Vaikuntha, the state deity of Lalitaditya's kingdom in Kashmir. In the early 9th century, Indian Hindu kings from Kanchipuram and the Pandyan king Srimara Srivallabha looted Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka. In the early 10th century, the Pratihara king Herambapala looted an image from a temple in the Sahi kingdom of Kangra, which in the 10th century was looted by the Pratihara king Yasovarman.[22][23][30]

In the early 11th century, the Chola king Rajendra I looted from temples in a number of neighbouring kingdoms, including Durga and Ganesha temples in the Chalukya Kingdom; Bhairava, Bhairavi and Kali temples in the Kalinga kingdom; a Nandi temple in the Eastern Chalukya kingdom; and a Siva temple in Pala Bengal. In the mid-11th century, the Chola king Rajadhiraja plundered a temple in Kalyani. In the late 11th century, the Hindu king Harsha of Kashmir plundered temples as an institutionalised activity. In the late 12th to early 13th centuries, the Paramara dynasty attacked and plundered Jain temples in Gujarat.[22][23][30] In the 1460s, Suryavamshi Gajapati dynasty founder Kapilendra sacked the Saiva and Vaishnava temples in the Cauvery delta in the course of wars of conquest in the Tamil country. Vijaynagara king Krishnadevaraya looted a Bala Krishna temple in Udayagiri in 1514, and he looted a Vittala temple in Pandharpur in 1520. Although different kings looted temples but civilians largely left unharmed.[22][23][30]

Under the Arabs (7th–8th century)

The first holy war or ghazwa was carried out in 644 AD against Thane. In the early 8th century, jihad was declared on Sindh by the Arab Caliphate.[33] Also during this time, Muslim armies attacked Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms in the northwest parts of the Indian subcontinent (now modern Pakistan and parts of Indian states of Gujarat, Rajasthan and Punjab). Muhammad bin Qasim and his army assaulted numerous towns, plundered them for wealth, enslaved Buddhists and Hindus, and destroyed temples and monasteries.[34] In some cases, they built mosques and minarets over the remains of the original temples, such as at Debal and later in towns of Nerun and Sadusan (Sehwan).[35] All those who bore arms were executed and their wives and children enslaved. One-fifth of the booty and slaves were dispatched back as khums tax to Hajjaj ibn Yusuf and the Caliph. Other people however were granted safe conduct or aman and allowed to continue as before. Custodians of temples were also enslaved.

As the third fitna, fourth fitna and other civil wars raged in Arab and Persian regions, and Sunni and Shia sects attempted to consolidate their positions, the religious violence in the western and northwest parts of Indian subcontinent against Hindus and Buddhists was limited to sporadic raids and attacks. In the late 8th century, the army of Abu Jafar al Mansur, under command of Amru bin Jamal attacked Hindu kingdoms in Barada and Kashmir, and took many children and women as slaves. The followers of Ali were expelled from Kandabil by Hisham, the governor of Sind.[36] Shia Muslims and sympathizers were expelled by Sunni armies after these raids. Similarly, adherents of Ali expelled Umayyad sympathizers and appointees.

However, due to facing defeats at the hands of multiple Indian kings, Arab forces ultimately failed to conquer the subcontinent. The victorious rulers included Nagabhata I of the Gurjara-Pratihara kingdom, Vikramaditya II of the Chalukya empire, Bappa Rawal of Mewar and Lalitaditya Muktapida of Kashmir.[37]

Minor dynasties (late 8th through 10th century)

The conflict between Hindus and Muslims in the Indian subcontinent may have begun with the Umayyad Caliphate in Sindh in 711. The state of Hindus during the Islamic expansion in India during the medieval period was characterised by destruction of temples, often illustrated by historians by the repeated destruction of the Hindu Temple at Somnath[38][39] and the anti-Hindu practices of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.[40]

About 986 AD, the raids and violence from Muslim army of Sultan Yaminud Daula Mahmud and Amir Sabuktigin reached the Hindu kingdom of Jayapala, extending from Upper Indus River valley to Punjab.[41] After several battles, the Hindu king Jaipal sent a message to Sabuktigin that the war be avoided. His son Mahmud replied with the message that his aim is to "obtain a complete victory suited to his zeal for the honor of Islam and Musulmans". King Jaipal then sent a new message to the Sultan and his Amir, stating "You have seen the impetuosity of the Hindus and their indifference to death. If you insist on war in the hope of obtaining plunder, tribute, elephants and slaves, then you leave us no alternative but to destroy our property, take the eyes out of our elephants, cast our families in fire, and commit mass suicide, so that all that will be left to you to conquer and seize is stones and dirt, dead bodies, and scattered bones."[42] Amir Sabuktigin then promised peace in exchange for a large ransom. King Jaipal, after receiving this peace offer, assumed that peace is likely and ordered his army to withdraw from a confrontation. According to 17th century Persian historian Firishta and the 11th-century historian Al-Utbi states that Jaipala reneged on the treaty and imprisoned Sabuktigin's ambassadors. Sabuktigin marched out and destroyed the homes of Hindus around Lamghan. He then conquered other cities and he killed many Hindus. Al-Utbi describes the number of those who died and were injured in his invasion as "beyond measure". He later claimed his victories in the name of Islam.[42][43]

Mahmud of Ghazni (11th century)

Mahmud of Ghazni was a Sultan who invaded the Indian subcontinent from present-day Afghanistan during the early 11th century. His campaigns included plundering and destruction of Hindu temples such as those at Mathura, Dwarka, and others. In 1024 AD, Mahmud attacked and the Hindu devotees, who John Keay presumes defend the temple instead of a standing army, fought him. He destroyed the third Somnath temple, killing over 50,000 around the temple and personally destroying the Shiva lingam after stripping it of its gold.[44][45] He made at least 17 raids into India.[46] The historian Al Utbi narrated the violence during war with Jaipala as,

That infidel remained where he was, avoiding the action for a long time ... The Sultan would not allow him to postpone the conflict, and the friends of God commenced the action, setting upon the enemy with sword, arrow and spear,—plundering, seizing and destroying ... The Hindus ... began ... to fight ... Swords flashed like lightning amid the blackness of clouds, and fountains of blood flowed like the fall of setting stars ... Noon had not arrived when the Musulmans had wrecked their vengeance on the infidel enemies of God, killing 15,000 of them, spreading them like a carpet over the ground, and making them food for beasts and birds of prey ... God also bestowed upon his [the Sultan's] friends such an amount of booty as was beyond all bounds and all calculation, including five hundred thousand slaves, beautiful men and women. The Sultan returned ... to his camp, having plundered immensely, by God's aid ... This ... took place on ... 27th November 1001.

Mohammed Ghori (1173–1206)

Mohammed Ghori raided north India and the Hindu pilgrimage site Varanasi at the end of the 12th century and he continued the destruction of Hindu temples and idols that had begun during the first attack in 1194.[48]

Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate, which extended over 320 years (1206–1526 AD), began with raids and invasion by Muhammad of Ghor. They were ruled by sultans and ghazis whose role was fighting against the non-Muslim kingdoms.[49]

Qutb-ud-din Aibak (1206–1210)

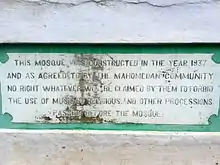

Historical records compiled by Muslim historian Maulana Hakim Saiyid Abdul Hai attest to the religious violence during Mamluk dynasty ruler Qutb-ud-din Aybak. The first mosque built in Delhi, the "Quwwat al-Islam" was built with demolished parts of 20 Hindu and Jain temples.[50][49][51] This pattern of iconoclasm was common during his reign.[52]

Ghiyas ud din Balban (1266–1287)

The Hindus like the Miwattis had rebelled after the reign of Shams-ud-din Iltutmish. Balban after becoming the Sultan started suppressing them and executed about 100,000 of them according to Firishta. At Kampil and Pattiali in Uttar Pradesh of today, he executed many rebels. At Kateher, located across Ramganga, he ordered a general massacre of the males, including boys of eight years old after a mutiny arose. The army made the Hindus surrender after chasing them in the jungles.[53][54]

Alauddin Khalji (1296–1316)

There was religious violence in India during the reign of Alauddin Khalji, of the Khalji dynasty.[56][57] The Khalji dynasty's court historian wrote (abridged),

The [Muslim] army left Delhi ... [in] Nov. 1310 ... After crossing those rivers, hills and many depths, ... elephants [were sent], ... in order that the inhabitants of Ma'bar might be aware that the day of resurrection had arrived amongst them; and that all the burnt Hindus would be despatched by the sword to their brothers in hell, so that fire, the improper object of their worship, might mete out proper punishment to them. The sea-resembling army moved swiftly, like a hurricane, to Ghurganw. Everywhere, ... the people who were destroyed were like trunks carried along in the torrent of the Jihun, or like straw tossed up and down in a whirlwind.

The new Muslims who rebelled in 1311 were crushed with mass executions, where all men and even boys above the age of 8 were seized and killed.[59] Nusrat Khan, a general of Alauddin Khalji, retaliated against mutineers by seizing all women and children of the affected area and placing them in prison. In another act, he had the wives of suspects arrested, dishonored and publicly exposed to humiliation. The children were cut into pieces on the heads of their mothers, on the orders of Nusrat Khan.[60]

The campaign of violence, abasement and humiliation was not merely the works of Muslim army, the kazis, muftis and court officials of Alauddin recommended it on religious grounds.[61] Kazi Mughisuddin of Bayánah advised Alauddin to "keep Hindus in subjection, in abasement, as a religious duty, because they are the most inveterate enemies of the Prophet, and because the Prophet has commanded us to slay them, plunder them, and make them captive; saying—convert them to Islam or kill them, enslave them and spoil their wealth and property."[61]

The Muslim army led by Malik Kafur, another general of Alauddin Khalji, pursued two violent campaigns into south India, between 1309 and 1311, against three Hindu kingdoms of Deogiri (Maharashtra), Warangal (Telangana) and Madurai (Tamil Nadu). Thousands were slaughtered. Halebid temple was destroyed. The temples, cities and villages were plundered. The loot from south India was so large, that historians of that era state a thousand camels had to be deployed to carry it to Delhi.[62] In the booty from Warangal was the Koh-i-Noor diamond.[63]

In 1311, Malik Kafur entered the Srirangam temple, massacred the Brahmin priests of the temple who resisted the invasion for three days, plundered the temple treasury and the storehouse and desecrated and destroyed numerous religious icons.[64][65]

Tughlaq Dynasty (1321–1394)

After Khalji dynasty, Tughlaq dynasty assumed power and religious violence continued in its reign. In 1323 Ulugh Khan began new invasions of the Hindu kingdoms of South India. At Srirangam, the invading army desecrated the shrine and killed 12,000 unarmed ascetics. The illustrious Vaishnava philosopher Sri Vedanta Desika, hid himself amongst the corpses together with the sole manuscript of the Srutaprakasika, the magnum opus of Sri Sudarsana Suri whose eyes were put out, and also the latter's two sons.[64][66][67][68]

Firuz Shah Tughluq was the third ruler of the Tughlaq dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate. The "Tarikh-i-Firuz Shah" is a historical record written during his reign that attests to the systematic persecution of Hindus under his rule.[69] Capture and enslavement was widespread; when Sultan Firuz Shah died, slaves in his service were killed en masse and piled up in a heap.[70] Victims of religious violence included Hindu Brahmin priests who refused to convert to Islam:

An order was accordingly given that the Brahman, with his tablet, should be brought into the presence of the Sultan ... The true faith was declared to the Brahman and the right course pointed out. but he refused to accept it ... The Brahman was tied hand and foot and cast into it [a pile of brushwood]; the tablet was thrown on the top and the pile was lighted ... The tablet of the Brahman was lighted in two places, at his head and at his feet ... The fire first reached his feet, and drew from him a cry, but the flames quickly enveloped his head and consumed him. Behold the Sultan's strict adherence to law and rectitude.

Under his rule, Hindus who were forced to pay the mandatory Jizya tax were recorded as infidels and their communities monitored. Hindus who erected a deity or built a temple and those who practised their religion in public such as near a kund (water tank) were arrested, brought to the palace and executed.[69][72] Firuz Shah Tughlaq wrote in his autobiography,

Some Hindus had erected a new idol-temple in the village of Kohana, and the idolaters used to assemble there and perform their idolatrous rites. These people were seized and brought before me. I ordered that the perverse conduct of the leaders of this wickedness be publicly proclaimed and they should be put to death before the gate of the palace. I also ordered that the infidel books, the idols, and the vessels used in their worship should all be publicly burnt. The others were restrained by threats and punishments, as a warning to all men, that no zimmi could follow such wicked practices in a Musulman country.

Timur's massacre of Delhi (1398)

The Muslim Turko-Mongol ruler Timur's invasion of Delhi was marked by systematic slaughter and other atrocities on a large scale, inflicted mainly on the Hindu population,[74] which was massacred or enslaved.[75] He also massacred the Indian Muslim population.[76] One hundred thousand prisoners, mainly Hindus as well as many Muslims, were killed before he attacked Delhi.[76] Many more were killed when he reached Delhi.[77][78]

[Timur's] soldiers grew more eager for plunder and destruction ... On that Friday night there were about 15,000 men in the city who were engaged from early eve till morning in plundering and burning the houses. In many places the impure infidel gabrs [of Delhi] made resistance ... On that Sunday, the 17th of the month, the whole place was pillaged, and several places in Jahan-panah and Siri were destroyed. On the 18th the like plundering went on. Every soldier obtained more than twenty persons as slaves, and some brought as many as fifty or a hundred men, women and children as slaves out of the city. The other plunder and spoils were immense, gems and jewels of all sorts, rubies, diamonds, stuffs and fabrics of all kinds, vases and vessels of gold and silver ... On the 19th of the month Old Delhi was thought of, for many infidel Hindus had fled thither ... Amir Shah Malik and Ali Sultan Tawachi, with 500 trusty men, proceeded against them, and falling upon them with the sword despatched them to hell.

Sikandar the Iconoclast (1399–1416)

After Timur left, different Muslim Sultans enforced their power in what used to be Delhi Sultanate. In Kashmir, Sultan Sikandar Shah Miri began expanding, and unleashed religious violence that earned him the name but-shikan or idol-breaker.[80] He earned this sobriquet because of the sheer scale of desecration and destruction of Hindu and Buddhist temples, shrines, ashrams, hermitages and other holy places in what is now known as Kashmir and its neighboring territories. He destroyed vast majority of Hindu and Buddhist temples in his reach in Kashmir region (north and northwest India).[81][82] Encouraged by Islamic theologian, Muhammad Hamadani, Sikandar Butshikan also destroyed ancient Hindu and Buddhist books and banned followers of dharmic religions from prayers, dance, music, consumption of wine and observation of their religious festivals.[83][84] To escape the religious violence during his reign, many Hindus converted to Islam and many left Kashmir. Many were also killed.[83]

Sayyid dynasty (1414–1451)

After the massacres of Timur, the people and lands within Delhi Sultanate were left in a state of anarchy, chaos and pestilence.[85] Sayyid dynasty followed, but few historical records on religious violence, or anything else for that matter, have been found. Those found, including Tarikh-i Mubarak-Shahi describe continued religious violence. From 1414–1423, according to the Muslim historian Yahya bin Ahmad, the Islamic commanders "chastised and plundered the infidels" of Ahar, Khur, Kampila, Gwalior, Seori, Chandawar, Etawa, Sirhind, Bail, Katehr and Rahtors.[86] The violence was not one sided. The Hindus retaliated by forming their own armed groups, and attacking forts seized by Muslims. In 1431, Jalandhar for example, was retaken by Hindus and all Muslims inside the fort were placed in prison. Yahya bin Ahmad, the historian remarked on the arrest of Muslims by Hindus, "the unclean ruthless infidels had no respect for the Musulman religion".[87] The cycle of violence between Hindus and Muslims, in numerous parts of India, continued throughout the Sayyid dynasty according to Yahya bin Ahmad.

Lodi dynasty (1451–1526)

Religious violence and persecution continued during the reign of the Lodi dynasty ruler, Sikandar Lodi. Delhi Sultanate's reach had shrunk to northern and eastern India. Sikandar made it a custom to destroy Hindu temples, example Mandrael and Utgir.[88] In 1499, a Brahmin of Bengal was arrested at Sambhal because he had attracted a large following among both Muslims and Hindus, with his teachings, "the Mohammedan and Hindu religions were both true, and were but different paths by which God might be approached." Sikandar, with his governor of Bihar Azam Humayun, asked Islamic scholars and sharia experts of their time whether such pluralism and peaceful messages were permissible within the Islamic Sultanate.[89] The scholars advised that it is not, and that the Brahmin should be given the option to either embrace and convert to Islam, or killed. Sikandar accepted the counsel and gave the Brahmin an ultimatum. The Hindu refused to change his view, and was killed.[89]

Elsewhere in Uttar Pradesh, a historian of Lodi dynasty times, described the state sponsored religious violence as follows,[90]

He (Lodi) was so zealous of a Musulman that he utterly destroyed diverse places of worship of the infidels. He entirely ruined the shrines of Mathura, the minefield of heathenism. Their stone images were given to the butchers to use them as meat weights,[91] and all the Hindus in Mathura were strictly prohibited from shaving their heads and beards, and performing ablutions. He stopped the idolatrous rites of the infidels there. Every city thus conformed as he desired to the customs of Islam. – Táríkh-i Dáúdí[92]

Mughal Empire

- Babur, Humayun, Suri dynasty (1526–1556)

Babur defeated and killed Ibrahim Lodi, the last Sultan of the Lodi dynasty, in 1526. Babur ruled for 4 years and was succeeded by his son Humayun whose reign was temporarily usurped by Suri dynasty. During their 30-year rule, religious violence continued in India. Records of the violence and trauma, from Sikh-Muslim perspective, include those recorded in Sikh literature of the 16th century.[93] The violence of Babur, the father of Humayun, in the 1520s, was witnessed by Guru Nanak, who commented upon them in four hymns. Historians suggest the early Mughal era period of religious violence contributed to introspection and then transformation from pacifism to militancy for self-defense in Sikhism.[93] According to autobiographical historical record of Emperor Babur, Tuzak-i Babari, Babur's campaign in northwest India targeted Hindu and Sikh pagans as well as apostates (non-Sunni sects of Islam), and immense number of infidels were killed, with Muslim camps building "towers of skulls of the infidels" on hillocks.[94] Baburnama, similarly records massacre of Hindu villages and towns by Babur's Muslim army, in addition to numerous deaths of both Hindu and Muslim soldiers in the battlefields.[95]

In 1545, Sher Shah Suri led a campaign of religious violence across western and eastern provinces of the Empire in India. As with theologians and court officials of Delhi Sultanate, his advisors counseled in favor of religious violence. Shaikh Nizam, for example, counseled, "There is nothing equal to a religious war against the infidels. If you be slain you become a martyr, if you live you become a ghazi."[96] Sher Shah's Mughal army then attacked the Hindu fort of Kalinjar, captured it, killing every Hindu infidel inside that fort.[96]

- Akbar (1556–1605)

Akbar is known for his religious tolerance. However, in early years of his reign, religious violence included the massacre of Hindus of Garha in 1560 AD, under the command of Mughal Viceroy Asaf Khan.[97][98] Other campaigns targeted Chitor and Rantambhor. Maulana Ahmad, the historian of that era, wrote of the battle at Chitor fort,

They (Hindus) committed jauhar (...). In the night, the (Muslim) assailants forced their way into the fortress in several places, and fell to slaughtering and plundering. At early dawn the Emperor went in mounted on an elephant, attended by his nobles and chiefs on foot. The order was given for a general massacre of the infidels as a punishment. The number exceeded 8,000 (Abu-l Fazl states there were 40,000 peasants with 8,000 Rajputs forming the garrison). Those who escaped the sword, men and women, were made prisoners and their property came into the hands of the Musulmans.

– Maulana Ahmad, Tarikh-i Alfi[99]

Another historian Nizamuddin Ahmad recorded the violence during the conquest of Nagarkot (modern Himachal Pradesh), as follows,

The fortress of Bhun, which is an idol temple of Mahámáí, was taken by valor of the (Muslim) assailants. A party of Rajputs, who had resolved to die, fought till they were all cut down. A number of Brahmins, who for many years had served the temple, never gave one thought to flight, and were killed. Nearly 200 black cows belonging to the Hindus, during the struggle, had crowded together for shelter in the temple. Some savage Turks, while the arrows and bullets were falling like rain, killed these cows one by one. They then took off their boots and filled them with the blood, and cast it upon the roof and walls of the temple.

– Nizamuddin Ahmad, Tabakat-i Akbari[99]

- Jahangir (1605–1627)

Nur-ud-din Mohammad Salim (Jahangir) was the fourth Mughal Emperor under whose reign religious violence was targeted at Hindus, Jains and Sikhs. A companion of Jahangir, and Muslim historian, described the religious violence as,[100]

One day at Ahmedabad, it was reported that many of the infidel and superstitious sect of the Seoras (Jains) of Gujarat has made several very great and splendid temples, and having placed in them their false gods, had managed to secure a large degree of respect for themselves. Emperor Jahangir ordered them to be banished from the country, and their temples to be demolished. Their idol was thrown down on the uppermost step of the mosque, that it might be trodden upon by those who came to say their daily prayers there. By this order of the Emperor, the infidels were exceedingly disgraced, and Islam exalted.

– Intikháb-i Jahangir-Shahi[100]

Jahangir's orders to torture and execute Guru Arjun, in 1606, is considered by scholars[101] to be a turning point in Sikh history, after which Sikhs considered militancy and religious violence against the Mughal Empire as necessary to protect their faith and loved ones. Violence against the Mughal Empire was thereafter viewed by the Sikhs as the only practical form of protest against religious persecution and Islamic orthodoxy.[102][103] The religious violence between Sikhs and Muslims increased thereafter, and ultimately led to the formal inauguration of khalsa (military brotherhood) in 1699 by the tenth Sikh guru, Gobind Singh.[104]

- Shah Jahan (1628–1658)

During Shah Jahan's reign, his soldiers attacked seven temples and "violently seized and appropriated them for their own use in Punjab".

- Aurangzeb (1658–1707)

Aurangzeb assumed power after arresting his father Shah Jahan, as well as eldest brother Dara Shikoh for his secular beliefs, and other blood relatives. Aurangzeb was a devout Sunni Muslim, and regarded his blood brother as a "pestilent infidel".[106] Aurangzeb put his brother on trial, found him guilty of apostasy, and executed him. He next arrested the children of Shikoh and poisoned them to death.[107] The reign of Aurangzeb that followed, witnessed one of the strongest campaigns of religious violence in Mughal Empire's history.[105] Aurangzeb re-introduced jizya (tax) on non-Muslims,[108] He led numerous campaigns of attacks against non-Muslims, destroyed Hindu temples,[109] arrested and executed the ninth Sikh guru Tegh Bahadur.[104][110]

Aurangzeb issued orders in 1669, to all his governors of provinces to "destroy with a willing hand the schools and temples of the infidels, and that they were strictly enjoined to put an entire stop to the teaching and practice of idolatrous forms of worship".[111] These orders and his own initiative in implementing them led to the destruction of numerous temples,[112] estimated between dozens to thousands,[113][114][115] though he also built many temples.[116] Some temples were destroyed entirely; in other cases mosques were built on their foundations, sometimes using the same stones. Idols were smashed, and the city of Mathura was temporarily renamed as Islamabad in local official documents.[111] Among the temples Aurangzeb destroyed included major Hindu pilgrimage sites in Varanasi, Mathura and Somnath temple in Gujarat.[117] In both cases, he had large mosques built on the sites.[110][117] On some destroyed sites such as Kesava Deva Temple in Mathura, Aurangzeb ordered the construction of mosque as replacement.[117][118]

Towns and provinces became depopulated from religious violence,[108] and Aurangzeb on his death bed lamented in writing that he had "greatly sinned" and "it should not happen that Muslims be killed and the blame for their death rest upon him".[119] Aurangzeb's Deccan campaign saw one of the largest death tolls in South Asian history, with an estimated 4.6 million people dead.[105] An estimated of 2.5 million of Aurangzeb's army were killed during the Mughal–Maratha Wars (100,000 annually during a quarter-century), while 2 million civilians in war-torn lands died due to drought, plague and famine.[120][105]

In Aurangzeb's time, there were also political leaders who destroyed temples, allied with Aurangzeb.[121]

Maratha Empire

- Atrocities in Bengal (1741–1751)

During the Maratha invasions of Bengal against Nawab of Bengal, the Marathas occupied Bihar[122] and western Bengal up to the Hooghly River.[123] During that time, the Maratha invaders, called "Bargi" in Bengali, perpetrated atrocities against the local population.[123] The Marathas reportedly plundered and burned villages, murdered pregnant women and infants, and gang-raped women.[124] An estimated 400,000 people were killed.[125][122]

During the invasion, the Marathas targeted Bengali Muslims, many of whom fled to take shelter in East Bengal, fearing for their lives in the wake of the Maratha attacks.[126] Many Bengali Hindus initially supported the Marathas, seeing them as liberators, but the Marathas also perpetrated many atrocities against Bengali Hindus,[127] who ended up opposing the Marathas and supporting the Muslim Nawab of Bengal.[122]

Sikh Empire

After seizing control of Kashmir, Maharaja Ranjit Singh's Sikh governors in Kashmir followed anti-Muslim policies, including the closure of the Jama Masjid of Srinagar.[128] In 1837, Raja Gulab Singh suppressed the revolt of the Yousafzai Tribe. Thousands of Muslim Pashtun tribe members were killed. Few hundred of captured women were sold as slaves in Jammu.[129]

After acquiring Jammu and Kashmir the Dogra Maharaja Ranbir Singh led a major invasion of the frontier areas of Yasin and Hunza to punish Muslim rebels in 1863. General Hooshiara Singh with 3,000 troops attacked the frontier with predominantly Muslim population. Thousands were killed during the invasion.[130][131][132]

Colonial Era

Goa Inquisition (1560–1774)

The first inquisitors, Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques, established themselves in what was formerly the king of Goa's palace, forcing the Portuguese viceroy to relocate to a smaller residence. The inquisitor's first act was forbidding Hindus from the public practice of their faith through fear of death. Sephardic Jews living in Goa, many of whom had fled the Iberian Peninsula to escape the excesses of the Spanish Inquisition to begin with, were also persecuted. During the Goa Inquisition, described as "contrary to humanity" by Voltaire,[133] conversions to Catholicism occurred by force and tens of thousands of Goan Hindus were massacred by the Portuguese between 1561 and 1774.[134][135]

The adverse effects of the inquisition forced hundreds of thousands of Hindus to escape Portuguese hegemony by migrating to other parts of the subcontinent.[136] Though officially repressed in 1774, it was reinstated by Queen Maria I in 1778. The vestiges of the Goa Inquisition were swept away when the British occupied the city in 1812.

Tipu Sultan (1782–1799)

The ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, was known to be anti-Hindu and anti-Christian,[137][138][139][140] pointing to the captivity of Hindus and Mangalorean Catholics at Seringapatam, which began on 24 February 1784 and ended on 4 May 1799, which remains a reminder of religious violence and persecution against that community.[141]

The Bakur Manuscript reports Tipu Sultan as having said: "All Musalmans should unite together, and considering the annihilation of infidels as a sacred duty, labor to the utmost of their power, to accomplish that subject."[142] Soon after the Treaty of Mangalore in 1784, Tipu gained control of Canara.[143] He is also said to have issued orders to seize the Christians in Canara, confiscate their estates,[144] and deport them to Seringapatam, the capital of his empire, through the Jamalabad fort route.[145] Father Miranda and other priests were expelled and fined by Tipu Sultan, then threatened with execution if they ever returned.[142]

Tipu also ordered the destruction of 27 Catholic churches,[142] all razed to the ground, with the exception of The Church of Holy Cross at Hospet, a demolition that was resisted by Jain Chauta Raja of Moodbidri.[146]

- Religious violence against Hindus

Hindus, particularly the Nair and Kodava communities were also persecuted by Tipu Sultan. They were subjected to forcible conversions to Islam, death, and torture.[147][148] The Nairs were treated with extreme brutality by the Muslims for their Hindu faith and martial tradition.[149][150][151] The captivity ended when Nair troops from Travancore, with the help of the East India Company defeated Tipu Sultan in the Third Anglo-Mysore War.[152][153] It is estimated that out of the 30,000 Nairs put to captivity (including women and children), most perished.[153][154]

In 1783, the Kodavas revolted and became subject of Tipu Sultan led religious violence.[155][156] Runmust Khan, the Nawab of Kurool, attacked the Kodavas. 500 were killed and over 40,000 Kodavas fled to the woods and hid in the mountains.[156] Thousands were seized, then forced to convert to Islam or face torture or death.[155] Estimates of victims vary. The British administrator Mark Wilks estimated the victims to be 70,000, historian Lewis Rice as well as Mir Kirmani stated the Coorg campaign victims included 80,000 men, women and child prisoners.[156] In a letter to Runmust Khan, Tipu himself stated:[157]

"We proceeded with the utmost speed, and, at once, made prisoners of 40,000 occasion-seeking and sedition-exciting Coorgis, who alarmed at the approach of our victorious army, had slunk into woods, and concealed themselves in lofty mountains, inaccessible even to birds. Then carrying them away from their native country, we raised them to the honour of Islam."

In 1788, Tipu ordered his governor in Calicut Sher Khan to begin the process of converting Hindus to Islam, and in July of that year, 20000 Brahmins were forcibly converted and made to eat beef.[158] Tipu sent a letter on 19 January 1790 to the Governor of Bekal, Budruz Zuman Khan. It says:

"Don't you know I have achieved a great victory recently in Malabar and over four lakh Hindus were converted to Islam? I am determined to march against that cursed Raman Nair (Rajah of Travancore) very soon. Since I am overjoyed at the prospect of converting him and his subjects to Islam, I have happily abandoned the idea of going back to Srirangapatanam now."[159]

Historians[160][161] state Tipu Sultan's reign illustrates "religious fanaticism and the excesses committed in the name of religion". The following is a translation of an inscription on the stone found at Seringapatam, which was situated in a conspicuous place in the fort:[162]

"Oh Almighty God! dispose the whole body of infidels! Scatter their tribe, cause their feet to stagger! Overthrow their councils, change their state, destroy their very root! Cause death to be near them, cut off from them the means of sustenance! Shorten their days! Be their bodies the constant object of their cares (i.e., infest them with diseases), deprive their eyes of sight, make black their faces (i.e., bring shame)."

- Religious violence against the Mangalorean Catholic community

According to Thomas Munro, around 60,000 people,[163] or 92 percent of the entire Mangalorean Catholic community, were captured by Tipu Sultan's army; only 7,000 escaped. They were force marched through the jungles and mountains of the Western Ghat range.[164]

According to British Government records, 20,000 of them died on the march to Seringapatam. According to James Scurry, a British officer, who was held captive along with Mangalorean Catholics, 30,000 of them were forcibly converted to Islam. The young women and girls were forcibly made wives of the Muslims living there.[164] The young men who offered resistance were disfigured by cutting their noses, upper lips, and ears.[165] Anyone who escaped from Seringapatam, when found was punished under the orders of Tipu Sultan, by cutting off of the ears, nose, the feet and one hand.[166] The Archbishop of Goa wrote in 1800, about the "oppression and sufferings experienced by the Christians under Tipu Sultan and Sultan's hatred of those who professed Christianity."[142]

Tipu Sultan's rule of the Malabar coast had an adverse impact on the Syrian Malabar Nasrani community. Many churches in the Malabar and Cochin were damaged, as well as old religious manuscripts were destroyed.[167] The destruction was systematic and witnessed over many years. Many Syrian Malabar Nasrani were killed or forcibly converted to Islam. Farms and property were also indiscriminately destroyed by the invading army. The Syrian Christian community fled to towns where there were already Christians. Some were given refuge in Cochin and Travancore.[167]

- Religious violence against British soldiers

Tipu's persecution of Christians extended to captured British soldiers. For instance, there were a significant number of forced conversions of British captives between 1780 and 1784. Following their defeat at the 1780 Battle of Pollilur, 7,000 British men along with an unknown number of women were held captive by Tipu in the fortress of Seringapatnam.[168] Of these, over 300 were circumcised and given Muslim names and clothes and several British regimental drummer boys were forced to dance and entertain the court.[168]

During the surrender of the Mangalore fort which was delivered in an armistice by the British and their subsequent withdrawal, all the Mestizos and remaining non-British foreigners were killed, together with 5,600 Mangalorean Catholics. Those condemned by Tipu Sultan for treachery were hanged instantly, the gibbets being weighed down by the number of bodies they carried. The Netravati River was so putrid with the stench of dying bodies, that the local residents were forced to leave their riverside homes.[142]

Indian Rebellion of 1857

In 1813, the East India Company charter was amended to allow for government sponsored missionary activity across British India.[169] The missionaries soon spread almost everywhere and started denigrating Hinduism and Islam, besides promoting Christianity, to seek converts.[170] Many officers of the British East India Company, such as Herbert Edwardes and Colonel S.G. Wheeler, openly preached to the Sepoys.[171] Such activities caused a great deal of resentment and fear of forced conversions among Indian soldiers of the Company and civilians alike.[170]

The perception that the company was trying to convert Hindus and Muslims to Christianity is often cited as one of the causes of the revolt. The revolt is considered by some historians as a semi-national and religious war seeking independence from British rule[172][173] though Saul David questions this interpretation.[174] The revolt started, among the Indian soldiers of British East India Company, when the British introduced new rifle cartridges, rumoured to be greased with pig and cow fat—an abhorrent concept to Muslim and Hindu soldiers, respectively, for religious reasons. However, in the aftermath of the revolt, British reprisals were particularly severe, with 100,000 being killed. The death toll is debated by historians, with figures ranging from 15,000 violently killed up to ten million killed by the food instability which followed.[175]

Partition of Bengal (1905)

The British colonial era, since the 18th century, portrayed and treated Hindus and Muslims as two divided groups, both in cultural terms and for the purposes of governance.[176] The colonists favoured Muslims in the early period of colonialism to gain influence in Mughal India, but underwent a shift in policies after the 1857 rebellion. A series of religious riots in the late 19th century, such as those of 1891, 1896 and 1897 religious riots of Calcutta, raised concerns within British Raj.[177] The rising political movement for independence of India, and colonial government's administrative strategies to neutralize it, pressed the British to make the first attempt to partition the most populous province of India, Bengal.[178]

Bengal was partitioned by the British, in 1905, along religious lines—a Muslim majority state of East Bengal and a Hindu majority state of West Bengal.[178] The partition was deeply resented, seen by both groups as evidence of British favoritism to the other side. Waves of religious riots hit Bengal through 1907. The religious violence worsened, and the partition was reversed in 1911. The reversal did little to calm the religious violence in India, and Bengal alone witnessed at least nine violent riots, between Muslims and Hindus, in the 1910s through the 1930s.[177][179]

Moplah Rebellion (1921)

Moplah Rebellion was an Anti Hindu rebellion conducted by the Muslim Mappila community (Moplah is a British spelling) of Kerala in 1921. Inspired by the Khilafat movement and the Karachi resolution; Moplahs murdered, pillaged, and forcibly converted thousands of Hindus.[180][181] 100,000 Hindus[182] were driven away from their homes forcing to leave their property behind, which were later taken over by Mappilas. This greatly changed the demographics of the area, being the major cause behind today's Malappuram district being a Muslim majority district in Kerala.[183]

According to one view, the reasons for the Moplah rebellion was religious revivalism among the Muslim Mappilas, and hostility towards the landlord Hindu Nair, Nambudiri Jenmi community and the British administration that supported the latter. Adhering to view, British records call it a British-Muslim revolt. The initial focus was on the government, but when the limited presence of the government was eliminated, Moplahs turned their full attention on attacking Hindus. Mohommed Haji was proclaimed the Caliph of the Moplah Khilafat and flags of Islamic Caliphate were flown. Ernad and Walluvanad were declared Khilafat kingdoms.[183]

Annie Besant wrote about the riots: "They Moplahs murdered and plundered abundantly, and killed or drove away all Hindus who would not apostatise. Somewhere about a lakh (100,000) of people were driven from their homes with nothing but their clothes they had on, stripped of everything. Malabar has taught us what Islamic rule still means, and we do not want to see another specimen of the Khilafat Raj in India."[182]

Partition of British India (1947)

Direct Action Day, which started on 16 August 1946, left approximately 3000 Hindus dead and 17000 injured.[184][185]

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British followed a divide-and-rule policy, exploiting differences between communities, to prevent similar revolts from taking place. In that respect, Indian Muslims were encouraged to forge a cultural and political identity separate from the Hindus.[186] In the years leading up to Independence, Mohammad Ali Jinnah became increasingly concerned about minority position of Islam in an independent India largely composed of a Hindu majority.[187]

Although a partition plan was accepted, no large population movements were contemplated. As India and Pakistan become independent, 14.5 million people crossed borders to ensure their safety in an increasingly lawless and communal environment. With British authority gone, the newly formed governments were completely unequipped to deal with migrations of such staggering magnitude, and massive violence and slaughter occurred on both sides of the border along communal lines. Estimates of the number of deaths range around roughly 500,000, with low estimates at 200,000 and high estimates at one million.[187]

Modern India

Large-scale religious violence and riots have periodically occurred in India since its independence from British colonial rule. The aftermath of the Partition of India in 1947 to create a separate Islamic state of Pakistan for Muslims, saw large scale sectarian strife and bloodshed throughout the nation. Since then, India has witnessed sporadic large-scale violence sparked by underlying tensions between sections of the Hindu and Muslim communities. These conflicts also stem from the ideologies of hardline right-wing groups versus Islamic Fundamentalists and prevalent in certain sections of the population. Since independence, India has always maintained a constitutional commitment to secularism. The major incidences include the 1969 Gujarat riots, 1984 anti-Sikh riots, the 1989 Bhagalpur riots, 1989 Kashmir violence, Godhra train burning, 2002 Gujarat riots, 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots and 2020 Delhi riots.

Exodus of Kashmiri Hindus

In the Kashmir region, approximately 300 Kashmiri Pandits were killed between September 1989 to 1990 in various incidents.[188] In early 1990, local Urdu newspapers Aftab and Al Safa called upon Kashmiris to wage jihad against India and ordered the expulsion of all Hindus choosing to remain in Kashmir.[188] In the following days masked men ran in the streets with AK-47 shooting to kill Hindus who would not leave.[188] Notices were placed on the houses of all Hindus, telling them to leave within 24 hours or die.[188]

Since March 1990, estimates of between 300,000 and 500,000 pandits have migrated outside Kashmir[189] due to persecution by Islamic fundamentalists in the largest case of ethnic cleansing since the partition of India.[190] The proportion of Kashmiri Pandits in the Kashmir valley has declined from about 15% in 1947 to, by some estimates, less than 0.1% since the insurgency in Kashmir took on a religious and sectarian flavour.[191]

Many Kashmiri Pandits have been killed by Islamist militants in incidents such as the Wandhama massacre and the 2000 Amarnath pilgrimage massacre.[192][193][194][195][196] The incidents of massacring and forced eviction have been termed ethnic cleansing by some observers.[188]

Gujarat communal riots (1969)

Religious violence broke out between Hindus and Muslims during September–October 1969, in Gujarat.[197] It was the most deadly Hindu-Muslim violence since the 1947 partition of India.[198][199]

The rioting started after an attack on a Hindu temple in Ahmedabad, but rapidly expanded to major cities and towns of Gujarat.[200] The violence included attacks on Muslim chawls by their Dalit neighbours.[199] The violence continued over a week, then the rioting restarted a month later.[200][201] Some 660 people were killed (430 Muslims, 230 Hindus), 1074 people were injured and over 48,000 lost their property.[199][202]

Anti-Sikh riots (1984)

In the 1970s, Sikhs in Punjab had sought autonomy and complained about domination by the Hindu.[203] Indira Gandhi government arrested thousands of Sikhs for their opposition and demands particularly during Indian Emergency.[203][204] In Indira Gandhi's attempt to "save democracy" through the Emergency, India's constitution was suspended, 140,000 people were arrested without due process, of which 40,000 were Sikhs.[205]

After the Emergency was lifted, during elections, she supported Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, a Sikh leader, in an effort to undermine the Akali Dal, the largest Sikh political party. However, Bhindranwale began to oppose the central government and moved his political base to the Darbar Sahib (Golden temple) in Amritsar, demanding creation on Punjab as a new country.[203] In June 1984, under orders from Indira Gandhi, the Indian army attacked the Golden temple with tanks and armoured vehicles, due to the presence of Sikh Khalistanis armed with weapons inside. Thousands of Sikhs died during the attack.[203] In retaliation for the storming of the Golden temple, Indira Gandhi was assassinated on 31 October 1984 by two Sikh bodyguards.

The assassination provoked mass rioting against Sikh.[203] During the 1984 anti-Sikh pogroms in Delhi, government and police officials aided Indian National Congress party worker gangs in "methodically and systematically" targeting Sikhs and Sikh homes.[206] As a result of the pogroms 10,000–17,000 were burned alive or otherwise killed, Sikh people suffered massive property damage, and at least 50,000 Sikhs were displaced.[207]

The 1984 riots fueled the Sikh insurgency movement. In the peak years of the insurgency, religious violence by separatists, government-sponsored groups, and the paramilitary arms of the government was endemic on all sides. Human Rights Watch reports that separatists were responsible for "massacre of civilians, attacks upon Hindu minorities in the state, indiscriminate bomb attacks in crowded places, and the assassination of a number of political leaders".[208] Human Rights Watch also stated that the Indian Government's response "led to the arbitrary detention, torture, extrajudicial execution, and enforced disappearance of thousands of Sikhs".[208] The insurgency paralyzed Punjab's economy until peace initiatives and elections were held in the 1990s.[208] Allegations of coverup and shielding of political leaders of Indian National Congress over their role in 1984 riot crimes, have been widespread.[209][210][211]

Religious involvement in North-East India militancy

Religion has begun to play an increasing role in reinforcing ethnic divides among the decades-old militant separatist movements in north-east India.[212][213][214]

The Christian separatist group National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT) has proclaimed bans on Hindu worship and has attacked animist Reangs and Hindu Jamatia tribesmen in the state of Tripura. Some resisting tribal leaders have been killed and some tribal women raped.

According to The Government of Tripura, the Baptist Church of Tripura is involved in supporting the NLFT and arrested two church officials in 2000, one of them for possessing explosives.[215] In late 2004, the National Liberation Front of Tripura banned all Hindu celebrations of Durga Puja and Saraswati Puja.[215] The Naga insurgency, militants have largely depended on their Christian ideological base for their cause.[216]

Anti-Hindu violence

There have been a number of attacks on Hindu temples and Hindus by Muslim militants and Christian evangelists. Prominent among them are the 1998 Chamba massacre, the 2002 fidayeen attacks on Raghunath temple, the 2002 Akshardham Temple attack by Islamic terrorist outfit Lashkar-e-Toiba[217] and the 2006 Varanasi bombings (also by Lashkar-e-Toiba), resulting in many deaths and injuries. Recent attacks on Hindus by Muslim mobs include Marad massacre and the Godhra train burning.

In August 2000, Swami Shanti Kali, a popular Hindu priest, was shot to death inside his ashram in the Indian state of Tripura. Police reports regarding the incident identified ten members of the Christian terrorist organisation, NLFT, as being responsible for the murder. On 4 Dec 2000, nearly three months after his death, an ashram set up by Shanti Kali at Chachu Bazar near the Sidhai police station was raided by Christian militants belonging to the NLFT. Eleven of the priest's ashrams, schools, and orphanages around the state were burned down by the NLFT.

In September 2008, Swami Laxmanananda, a popular regional Hindu Guru was murdered along with four of his disciples by unknown assailants (though a Maoist organisation later claimed responsibility for that[218][219]). Later the police arrested three Christians in connection with the murder.[220] Congress MP Radhakant Nayak has also been named as a suspected person in the murder, with some Hindu leaders calling for his arrest.[221]

Lesser incidents of religious violence happen in many towns and villages in India. In October 2005, five people were killed in Mau in Uttar Pradesh during Muslim rioting, which was triggered by the proposed celebration of a Hindu festival.[222]

On 3 and 4 January 2002, eight Hindus were killed in Marad, near Kozhikode due to scuffles between two groups that began after a dispute over drinking water.[223][224] On 2 May 2003, eight Hindus were killed by a Muslim mob, in what is believed to be a sequel to the earlier incident.[224][225] One of the attackers, Mohammed Ashker was killed during the chaos. The National Development Front (NDF), a right-wing militant Islamist organisation, was suspected as the perpetrator of the Marad massacre.[226]

In the 2010 Deganga riots after hundreds of Hindu business establishments and residences were looted, destroyed and burnt, dozens of Hindus were killed or severely injured and several Hindu temples desecrated and vandalised by the Islamist mobs allegedly led by Trinamul Congress MP Haji Nurul Islam.[227] Three years later, during the 2013 Canning riots, several hundred Hindu businesses were targeted and destroyed by Islamist mobs in the Indian state of West Bengal.[228][229]

Religious violence has led to the death, injuries and damage to numerous Hindus.[230][231] For example, 254 Hindus were killed in 2002 Gujarat riots out of which half were killed in police firing and rest by rioters.[232][233][234] During 1992 Bombay riots, 275 Hindus died.[235]

In October, 2018, a Christian personal security officer of an additional sessions judge assassinated his 38-year-old wife and his 18-year-old son for not converting to Christianity.[236]

Violence against Muslims

The history of modern India has many incidents of communal violence. During the 1947 partition there was religious violence between Muslim-Hindu, Muslim-Sikhs and Muslim-Jains on a gigantic scale.[28] Hundreds of religious riots have been recorded since then, in every decade of independent India. In these riots, the victims have included many Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Christians and Buddhists.

On 6 December 1992, members of the Vishva Hindu Parishad and the Bajrang Dal destroyed the 430-year-old Babri Mosque in Ayodhya[237][238]—it was claimed by the Hindus that the mosque was built over the birthplace of the ancient deity Rama (and a 2010 Allahabad court ruled that the site was indeed a Hindu monument before the mosque was built there, based on evidence submitted by the Archaeological Survey of India[239]). The resulting religious riots caused at least 1200 deaths.[240][241] Since then the Government of India has blocked off or heavily increased security at these disputed sites while encouraging attempts to resolve these disputes through court cases and negotiations.[242]

In the aftermath of the destruction of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya by Hindu nationalists on 6 December 1992, riots took place between Hindus and Muslims in the city of Mumbai. Four people died in a fire in the Asalpha timber mart at Ghatkopar, five were killed in the burning of Bainganwadi; shacks along the harbour line track between Sewri and Cotton Green stations were gutted; and a couple was pulled out of a rickshaw in Asalpha village and burnt to death.[243] The riots changed the demographics of Mumbai greatly, as Hindus moved to Hindu-majority areas and Muslims moved to Muslim-majority areas.

The Godhra train burning incident in which Hindus were burned alive allegedly by Muslims by closing door of train, led to the 2002 Gujarat riots in which mostly Muslims were killed. According to the death toll given to the parliament on 11 May 2005 by the United Progressive Alliance government, 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus were killed, and another 2,548 injured. 223 people are missing. The report placed the number of riot widows at 919 and 606 children were declared orphaned.[244][245][246] According to hone advocacy group, the death tolls were up to 2000.[247][248][249][250][251] According to the Congressional Research Service, up to 2000 people were killed in the violence.[252]

Tens of thousands were displaced from their homes because of the violence. According to New York Times reporter Celia Williams Dugger, witnesses were dismayed by the lack of intervention from local police, who often watched the events taking place and took no action against the attacks on Muslims and their property.[253] Sangh leaders[254][255] as well as the Gujarat government[256][257] maintain that the violence was rioting or inter-communal clashes—spontaneous and uncontrollable reaction to the Godhra train burning.

The Government of India has implemented almost all the recommendations of the Sachar Committee to help Muslims.[258][259]

The February 2020 North East Delhi riots, which left more than 40 dead and hundreds injured, were triggered by protests against a citizenship law seen by many critics as anti-Muslim and part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Hindu nationalist agenda.[260][261][262]

Anti-Christian violence

A 1999 Human Rights Watch report states increasing levels of religious violence on Christians in India, perpetrated by Hindu organizations.[263][264] In 2000, acts of religious violence against Christians included forcible reconversion of converted Christians to Hinduism, distribution of threatening literature and destruction of Christian cemeteries.[263] According to a 2008 report by Hudson Institute, "extremist Hindus have increased their attacks on Christians, until there are now several hundred per year. But this did not make news in the U.S. until a foreigner was attacked."[265] In Orissa, starting December 2007, Christians have been attacked in Kandhamal and other districts, resulting in the deaths of two Hindus and one Christian, and the destruction of houses and churches. Hindus claim that Christians killed a Hindu saint Laxmananand, and the attacks on Christians were in retaliation. However, there was no conclusive proof to support this claim.[266][267][268][269][270] Twenty people were arrested following the attacks on churches.[269] Similarly, starting 14 September 2008, there were numerous incidents of violence against the Christian community in Karnataka.

In 2007, foreign Christian missionaries became targets of attacks.[271]

Graham Stuart Staines (1941 – 23 January 1999) an Australian Christian missionary who, along with his two sons Philip (aged 10) and Timothy (aged 6), was burnt to death by a gang of Hindu Bajrang Dal fundamentalists while sleeping in his station wagon at Manoharpur village in Kendujhar district in Odisha, India on 23 January 1999. In 2003, a Bajrang Dal activist, Dara Singh, was convicted of leading the gang that murdered Graham Staines and his sons, and was sentenced to life in prison.[272]

In its annual human rights reports for 1999, the United States Department of State criticised India for "increasing societal violence against Christians."[276] The report listed over 90 incidents of anti-Christian violence, ranging from damage of religious property to violence against Christian pilgrims.[276]

In Madhya Pradesh, unidentified persons set two statues inside St Peter and Paul Church in Jabalpur on fire.[277] In Karnataka, religious violence was targeted against Christians in 2008.[278]

Anti-atheist violence

Statistics

| Year | Incidents | Deaths | Injured |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 779 | 124 | 2066 |

| 2006 | 698 | 133 | 2170 |

| 2007 | 761 | 99 | 2227 |

| 2008 | 943 | 167 | 2354 |

| 2009 | 849 | 125 | 2461 |

| 2010 | 701 | 116 | 2138 |

| 2011 | 580 | 91 | 1899 |

| 2012 | 668 | 94 | 2117 |

| 2013 | 823 | 133 | 2269 |

| 2014 | 644 | 95 | 1921 |

| 2015 | 751 | 97 | 2264 |

| 2016 | 703 | 86 | 2321 |

| 2017 | 822 | 111 | 2384 |

From 2005 to 2009, an average of 130 people died every year from communal riots, and 2,200 were injured.[8] In pre-partitioned India, over the 1920–1940 period, numerous communal violence incidents were recorded, an average of 381 people died per year during religious violence, and thousands were injured.[285]

According to PRS India,[8] 24 out of 35 states and union territories of India reported instances of religious riots over the five years from 2005 to 2009. However, most religious riots resulted in property damage but no injuries or fatalities. The highest incidences of communal violence in the five-year period were reported from Maharashtra (700). The other three states with high counts of communal violence over the same five-year period were Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Orissa. Together, these four states accounted for 64% of all deaths from communal violence. Adjusted for widely different population per state, the highest rate of communal violence fatalities were reported by Madhya Pradesh, at 0.14 death per 100,000 people over five years, or 0.03 deaths per 100,000 people per year.[8] There was a wide regional variation in rate of death caused by communal violence per 100,000 people. The India-wide average communal violence fatality rate per year was 0.01 person per 100,000 people per year. The world's average annual death rate from intentional violence, in recent years, has been 7.9 per 100,000 people.[286]

For 2012,[9] there were 93 deaths in India from many incidences of communal violence (or 0.007 fatalities per 100,000 people). Of these, 48 were Muslims, 44 Hindus and one police official. The riots also injured 2,067 people, of which 1,010 were Hindus, 787 Muslims, 222 police officials and 48 others. Over 2013, 107 people were killed during religious riots (or 0.008 total fatalities per 100,000 people), of which 66 were Muslims, 41 were Hindus. The various riots in 2013 also injured 1,647 people including 794 Hindus, 703 Muslims and 200 policemen.[9][287]

International human rights reports

- The 2007 United States Department of State International Religious Freedom Report noted The Constitution provides for freedom of religion, and the National Government generally respected this right in practice. However, some state and local governments limited this freedom in practice.[288]

- The 2008 Human Rights Watch report notes: India claims an abiding commitment to human rights, but its record is marred by continuing violations by security forces in counterinsurgency operations and by government failure to rigorously implement laws and policies to protect marginalised communities. A vibrant media and civil society continue to press for improvements, but without tangible signs of success in 2007.[7]

- The 2007 Amnesty International report listed several issues concern in India and noted Justice and rehabilitation continued to evade most victims of the 2002 Gujarat communal violence.[289]

- The 2007 United States Department of State Human Rights Report[290] noted that the government generally respected the rights of its citizens; however, numerous serious problems remained. The report which has received a lot of controversy internationally,[291][292][293][294] as it does not include human rights violations of United States and its allies, has generally been rejected by political parties in India as interference in internal affairs,[295] including in the Lower House of Parliament.[296]

- In a 2018 report, United Nations Human Rights office expressed concerns over attacks directed at minorities and Dalits in India. The statement came in an annual report to the United Nations Human Rights Council's March 2018 session where Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein said,

"In India, I am increasingly disturbed by discrimination and violence directed at minorities, including Dalits and other scheduled castes, and religious minorities such as Muslims. In some cases this injustice appears actively endorsed by local or religious officials. I am concerned that criticism of government policies is frequently met by claims that it constitutes sedition or a threat to national security. I am deeply concerned by efforts to limit critical voices through the cancellation or suspension of registration of thousands of NGOs, including groups advocating for human rights and even public health groups."[297]

In film and literature

Religious violence in India have been a topic of various films and novels.

- Firaaq, a film set in the aftermath of the 2002 Gujarat riots

- Garam Hawa, a film by M. S. Sathyu based on a story on partition written by Ismat Chugtai

- Gandhi, a 1982 film which included portrayal of the Direct Action Day and Partition riots

- Tamas, a film on partition based on a book by Bhisham Sahni

- Bombay, a 1995 film centred on events during the period of December 1992 to January 1993 in India, and the controversy surrounding the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya[298]

- Maachis, a film by Gulzar about Punjab terrorism

- Earth, a 1998 film[299] portraying Partition violence in Lahore

- Fiza, a 2000 film[300] set amidst the Bombay riots

- Hey Ram, a 2002 film[301] with a semi-fictional plot centred around Partition of India and related religious violence

- Mr. and Mrs. Iyer, a 2002 film[302] about the relationship between two lead characters Meenakshi Iyer and Raja amidst Hindu-Muslim riots in India

- Final Solution, a 2003 documentary film about the 2002 Gujarat violence, banned in India[303]

- Hawayein, a 2003 film about the struggles of Sikhs during the 1984 anti-Sikh riots

- Black Friday, a Hindi film on the 1993 serial bomb blasts in Mumbai, directed by Anurag Kashyap[304]

- Amu, a film about a girl orphaned during the 1984 anti-Sikh riots

- Parzania, a 2007 film about the riots in Gujarat in 2002[305] The film was purposely not released in Gujarat.[306][307] Cinema owners and distributors in Gujarat refused to screen the film out of fear of retaliation by Hindu activists.[308] Hindutva groups in Gujarat threatened to attack theatres that showed the film.[308]

- Slumdog Millionaire, a 2008 British crime drama film that is a loose adaptation of the novel Q & A (2005) by Indian author Vikas Swarup, telling the story of 18-year-old Jamal Malik from the Juhu slums of Mumbai. The violence of the Bombay riots is an instrumental part of the plot of the film as the protagonist, Jamal Malik's mother is among those killed in the riots, and he later remarks "If it wasn't for Rama and Allah, we'd still have a mother."

- Train to Pakistan, a novel by Khushwant Singh set during the Partition of India, and a movie by the same name, based on the book

- "Toba Tek Singh", a satirical story by Saadat Hasan Manto set during the Partition of India

- Muzaffarnagar Abhi Baki Hai, a documentary on the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riot[309]

- Punjab 1984, a 2014 Indian Punjabi period drama film based on the 1984–86 Punjab insurgency's impact on social life

- Man with the White Beard, 2018 fiction by Dr Shah Alam Khan set in the backdrop of three major riots of India: the anti Sikh riots of 1984, the anti Muslim riots of Gujarat in 2002 and the anti Christian riots of Kandhamal in 2008[310]

See also

- Caste-related violence in India

- Religious harmony in India

- Communalism (South Asia)

- Hindu–Islamic relations

- Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunal) Act, 1983

- Islamic terrorism in India during 21st century

- Madhe Sahaba Agitation

- List of massacres in India

- List of riots in India

- List of riots in Mumbai

- Persecution of atheists

- Persecution of Christians

- Persecution of Hindus

- Persecution of Muslims

- Religion in India

- Saffron Terror

- Terrorism in India

- Violence against Muslims in India

- 1925 Indian riots

References

- "Census of India: Population by religious communities". 2001.

- (A) Violette Graff and Juliette Galonnier (2013), Hindu-Muslim Communal Riots in India II (1986–2011) Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, SciencesPo, Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Paris, France; (B) Violette Graff and Juliette Galonnier (2013), Hindu-Muslim Communal Riots in India I (1947–1986) Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, SciencesPo, Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Paris, France

- Rao, Prabhakar (December 2007). "Should religions try to convert others?".

- "Teachings of religious tolerance and intolerance in world religions".

- Subrahmaniam, Vidya (6 November 2003). "Ayodhya: India's endless curse".

- "A new breed of missionary". The Christian Science Monitor. 1 April 2005.

- "India:Events of 2007". Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- Vital Stats - Communal Violence in India PRS India, Centre for Policy Research (CPR), New Delhi

- Bharti Jain, Government releases data of riot victims identifying religion The Times of India (September 2013); Note: Indian government calendar reporting period ends in June every year.

- ANNUAL REPORT OF THE U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM (PDF) (Report). U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM. April 2018. p. 37.

- "States Where Cow Slaughter is Banned So Far, and States Where it Isn't".

- "Tracking mob lynching in two charts".

- "India's Got Beef With Beef: What You Need To Know About The Country's Controversial 'Beef Ban'".

- Pulsipher, Lydia Mihelic; Pulsipher, Alex (14 September 2007). World Regional Geography. Macmillan. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-7167-7792-2.

Many historians argue that the Partition could have been avoided had it not been for the "divide-and-rule" tactics the British used throughout the colonial era to heighten tensions between South Asian Muslims and Hindus, thus creating a role for themselves as indispensable and benevolent mediators. For example, British local administrators commonly favored the interests of minority communities in order to weaken the power of majorities that could have threatened British authority. The legacy of these "divide-and-rule" tactics includes not only the Partition, but also the repeated wars and skirmishes, strained relations, and ongoing arms race between India and Pakistan.

- John S. Strong (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Beni Madhab Barua (5 May 2010). The Ajivikas. General Books. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-1-152-74433-2. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Steven L. Danver, ed. (22 December 2010). Popular Controversies in World History: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions. ABC-CLIO. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Le Phuoc (March 2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Article on Deorkothar Stupas possibly being targeted by Pushyamitra". Archaeology.org. 4 April 2001. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- Andy Rotman (Translator), Paul Harrison et al (Editors), Divine Stories - The Divyāvadāna Part 1, Wisdom Publications, Boston, ISBN 0-86171-295-1, Introduction, Preview summary of book

- Durant, Will. The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage. p. 459.

The Mohammedan Conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilization is a precarious thing, whose delicate complex of order and liberty, culture and peace may at any time be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within. The Hindus had allowed their strength to be wasted in internal division and war; they had adopted religions like Buddhism and Jainism, which unnerved them for the tasks of life; they had failed to organize their forces for the protection of their frontiers and their capitals, their wealth and their freedom, from the hordes of Scythians, Huns, Afghans and Turks hovering about India's boundaries and waiting for national weakness to let them in. For four hundred years (600–1000 A.D.) India invited conquest; and at last it came.

- Eaton, Richard M. (December 2000). "Temple desecration in pre-modern India". Frontline. Vol. 17 no. 25. The Hindu Group.

- Eaton, Richard M. (September 2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States". Journal of Islamic Studies. 11 (3): 283–319. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283.

- Will Durant (1976), The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0671548001, p. 458, Quote: "The Mohammedan Conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilization is a precarious thing, whose delicate complex of order and liberty, culture and peace may at any time be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within. The Hindus had allowed their strength to be wasted in internal division and war; they had adopted religions like Buddhism and Jainism, which unnerved them for the tasks of life; they had failed to organize their forces for the protection of their frontiers and their capitals."

- Caste in Muslim Society by Yoginder Sikand