Effects of climate change on South Asia

The effects of climate change on South Asia are significant, and are expected to intensify as global temperatures rise due to climate change. In the 2017 edition of Germanwatch's Climate Risk Index, two countries in South Asia — Bangladesh and Pakistan — ranked sixth and seventh respectively as the countries most affected by climate change in the period from 1996 to 2015, while another — India — ranked fourth among the list of countries most affected by climate change in 2015.[1] The region, home to 1.947 billion people,[2] is one of the most vulnerable regions globally to a number of direct and indirect effects of climate change, including sea level rise, cyclonic activity, and changes in ambient temperature and precipitation patterns. Ongoing sea level rise has already submerged several low-lying islands in the Sundarbans region, displacing thousands of people.

Among the countries of South Asia, Bangladesh is likely to be the worst affected by climate change. This is owing to a combination of geographical factors, such as its flat, low-lying, and delta-exposed topography,[3] and socio-economic factors, including its high population density, levels of poverty, and dependence on agriculture.[4] Its sea level, temperature, and evaporation are increasing, and the changes in precipitation and cross-boundary river flows are already beginning to cause drainage congestion. There is a reduction in freshwater availability, disturbance of morphological processes, and a higher intensity of flooding.

Temperature

As per the IPCC, depending upon the scenario visualized, the projected global warming average surface will result in worldwide temperature increase at the end of the 21st Century in relative to the end of the 20th Century ranges from 0.6 to 4 °C.[5]

Regarding local temperature rises, the IPCC figure shows that mean annual value of temperature rise by the end of the century in South Asia is 3.3 °C with the min-max range as 2.7 – 4.7 °C. The mean value for Tibet would be higher with mean increase of 3.8 °C and min-max figures of 2.6 and 6.1 °C respectively, which implies harsher warming conditions for the Himalayan watersheds.[6]

Rise in sea level

The global average sea level rose by 3.1 mm per year from 1993 to 2003.[5] More recent analysis of a number of semi empirical models predict a sea level rise of about 1 metre by the year 2100. [7] Ongoing sea level rises have already submerged several low-lying islands in the Sundarbans, displacing thousands of people.[8] Temperature rises on the Tibetan Plateau are causing Himalayan glaciers to retreat. It has been predicted that the historical city of Thatta and Badin, in Sindh, Pakistan would have been swallowed by the sea by 2025, as the sea is already encroaching 80 acres of land here, every day. [9]

In October 2019, a study was published in the Nature Communications journal. The journal claims that the number of people who will be impacted from sea level rise during 21st century is 3 times higher than the previous expected number. By the year 2050, 150 million will be under the water line during high tide and 300 million will live in zones with flooding every year. By the year 2100, those numbers differ sharply depending on the emission scenario. In a low emission scenario, 140 million will be under water during high tide and 280 million will have flooding each year. In high emission scenario, the numbers reach up to 540 million and 640 million, respectively. 70% of these people will live in 8 countries in Asia: China, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Japan, and the Philippines. Large parts of Ho Chi Minh City, Mumbai, Shanghai, Bangkok and Basra could be inundated.[10][11]

Population that will live in a zone of annual flooding by the year 2050 in millions, in 6 countries in Asia, according to old and new estimates:[12]

| Country | Old estimate | New estimate |

|---|---|---|

| China | 29 | 93 |

| Bangladesh | 5 | 42 |

| India | 5 | 36 |

| Vietnam | 9 | 31 |

| Indonesia | 5 | 23 |

| Thailand | 1 | 12 |

Observed changes in the natural and human environment

Environmental

Increased landslides and flooding are projected to have an impact upon states such as Assam.[13] Ecological disasters, such as a 1998 coral bleaching event that killed off more than 70% of corals in the reef ecosystems off Lakshadweep and the Andamans, and was brought on by elevated ocean temperatures tied to global warming, are also projected to become increasingly common.[14][15][16]

Bangladesh is the first country among the countries to be affected by severe climate change. Its sea level, temperature and evaporation are increasing, and the changes in precipitation and cross boundary river flows are already beginning to cause drainage congestion. There is a reduction in fresh water availability, disturbance of morphologic processes and a higher intensity of flooding and other such disasters. Bangladesh only contributes 0.1% of the world's emissions yet it has 2.4% of the world's population. In contrast, the United States makes up about 5 percent of the world's population, yet they produce approximately 25 percent of the pollution that causes global warming.[17]

Heat waves' frequency and power are increasing in India because of climate change. In 2019, the temperature reached 50.6 degrees Celsius, 36 people were killed. 15 monkeys died from heat stroke after another group of monkeys prevented them from accessing the closest water source. The high temperatures are expected to impact 23 states in 2019, up from nine in 2015 and 19 in 2018. The number of heat wave days has increased — not just day temperature, night temperatures increased also. 2018 was the country's sixth hottest year on record, and 11 of its 15 warmest years have occurred since 2004. The capital of New Delhi broke its all-time record with a high of 48 degrees Celsius.[18]

"Science as well as our subjective experiences has made it unequivocally clear that longer, hotter and deadlier summers are poised to become the norm due to climate change," environmental researcher Hem Dholakia wrote"

Today, because of global warming, the world is one degree Celsius warmer than it was before the industrial revolution. According to author Wallace-Wells, if the temperature rises even one more degree, “Cities now home to millions, across India and the Middle East, would become so hot that stepping outside in summer would be a lethal risk.” In India, exposure to heat waves is said to increase by 8 times between 2021 and 2050, and by 300% by the end of this century. (See article: “Heat wave exposure in India in current, 1.5 °C, and 2.0 °C worlds,” in the journal Environmental Research Letters). The number of Indians exposed to heat waves increased by 200% from 2010 to 2016. Heat waves also affect farm labour productivity. The heat waves affect central and northwestern India the most, and the eastern coast and Telangana have also been affected. In 2015, the latter places witnessed at least 2500 deaths. For the first time in history, Kerala reported a heat wave in 2016. The government is being advised by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology in predicting and mitigating heat waves. The government of Andhra Pradesh, for instance, is creating a Heat Wave Action Plan.[19]

The heat wave has closed schools and universities.

Overall, however, the death toll from India's heat waves has decreased in the last four years. More than 2,000 people died in 2015, 375 in 2017 and 20 in 2018. "Officials say this is because the government has made an effort to reduce the death toll by encouraging residents to reduce or alter the time spent working on hot days and by providing free drinking water to hard-hit populations". It also used water to cool streets and forced police to guard water tankers in Madhya Pradesh state after fights over supply turned deadly. Those measures cost a lot of money and water, and the government's resources was limited this year by the country's national election. The heat wave may continue, as monsoon rains have been delayed this year.[20]

Economic

India has the world's highest social cost of carbon.[21] The Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research has reported that, if the predictions relating to global warming made by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change come to fruition, climate-related factors could cause India's GDP to decline by up to 9%; contributing to this would be shifting growing seasons for major crops such as rice, production of which could fall by 40%. Around seven million people are projected to be displaced due to, among other factors, submersion of parts of Mumbai and Chennai, if global temperatures were to rise by a mere 2 °C (3.6 °F).[22]

Villagers in India's North Eastern state of Meghalaya are also concerned that rising sea levels will submerge neighboring low-lying Bangladesh, resulting in an influx of refugees into Meghalaya which has few resources to handle such a situation.[23][24]

If severe climate changes occur, Bangladesh will lose land along the coast line.[25] This will be highly damaging to Bangladeshis especially because about 50% population of Bangladeshis are employed in the agriculture sector,[26] with rice as the largest production.[27][28] If no further steps are taken to improve the current conditions global warming will affect the economy severely worsening the present issues further.[29] The climate change would increase expenditure towards health care, cool drinks, alcoholic beverages, air conditioners, ice cream, cosmetics, agricultural chemicals, and other products.[30]

Furthermore, the reliance on exportation of goods for economic stability causes cascading effects contributing to climate change by the changes to land modifications to keep up with global demands. This is especially true in China. Environmental factor#Socioeconomic Drivers

Social

Climate Change in India and Pakistan will have a disproportionate impact on the more than 400 million that make up India's poor. This is because so many depend on natural resources for their food, shelter and income. More than 56% of people in India work in agriculture, while in Pakistan 43℅ of its population work in agriculture while many others earn their living in coastal areas.[31]

Pollution

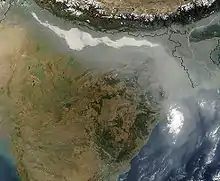

Thick haze and smoke, originating from burning biomass in northeastern India[32] and air pollution from large industrial cities in northern India,[33] often concentrate inside the Ganges Basin. Prevailing westerlies carry aerosols along the southern margins of the steep-faced Tibetan Plateau to eastern India and the Bay of Bengal. Dust and black carbon, which are blown towards higher altitudes by winds at the southern faces of the Himalayas, can absorb shortwave radiation and heat the air over the Tibetan Plateau. The net atmospheric heating due to aerosol absorption causes the air to warm and convect upwards, increasing the concentration of moisture in the mid-troposphere and providing positive feedback that stimulates further heating of aerosols.[33] Pollution of mercury in India is shocking. The environment is being packed with approximately 70 tonnes of mercury per year by existing mercury-cell plants. One gram of mercury is sufficient to pollute a lake of surface area of around 20 acres that would harm the fish which as a result would be dangerous to consume.[34]

Awareness

Indian and Pakistani media can contribute to increased awareness of climate change and related issues. A qualitative analysis of some mainstream Indian newspapers (particularly opinion and editorial pieces) during the release of the IPCC 4th Assessment Report and during the Nobel Peace Prize win by Al Gore and the IPCC found that Indian media strongly pursue the frame of scientific certainty in their coverage of climate change. This is in contrast to the skepticism displayed by American newspapers at the time. Alongside, Indian media highlight frames of energy challenge, social progress, public accountability and looming disaster. This sort of coverage finds parallels in European media narratives as well and helps build a transnational, globalized discourse on climate change.[35] Another study has found that the media in India are divided along the lines of a north–south, risk-responsibility discourse.[36] However, much more research is required to analyse Indian media's role in shaping public perceptions on climate change.

Tribal people in India's remote northeast plan to [37] honor former U.S. Vice President Al Gore with an award for promoting awareness on climate change that they say will have a devastating impact on their homeland.

Meghalaya- meaning 'Abode of the Clouds' in Hindi—is home to the towns of Cherrapunji and Mawsynram, which are credited with being the wettest places in the world due to their high rainfall. But scientists state that global climate change is causing these areas to experience an increasingly sparse and erratic rainfall pattern and a lengthened dry season,[38] affecting the livelihoods of thousands of villagers who cultivate paddy and maize. Some areas are also facing water shortages.

People are becoming aware of ills of global warming. Taking initiative on their own people from Sangamner, Maharashtra (near Shirdi) have started a campaign of planting trees known as Dandakaranya- The Green Movement. It was started by visionary & ace freedom fighter the late Shri Bhausaheb Thorat in the year 2005. To date, they have sowed more than 12 million seeds & planted half a million plants.

According to data from 2009 India is the world's third biggest emitter of CO2 after China and the United States – pushing Russia into fourth place.[39]

Potential Solutions

There are many concrete steps which can be taken to address the threat of climate change. Incentives can be provided for electric vehicles or public transport and this curb the impact of the transportation sector. However, though these suggestions have been made, there is no political will to carry them out. Households can be given electricity and slowly phasing out LPG (the current trend is to increase the usage of the latter). Rainwater can be harvested and the rivers could be restored to their original flow so that they can bring back the wetlands and the natural ways of silt, nutrient and wildlife flow. All of these use technologies and can be implemented by the 11-year period the IPCC has stipulated before which any change must be made if we are to evade the adverse effects of climate change. So far, though the initiatives by the Delhi Metro to switch to solar power- or similar efforts by the Kochi airport-are a step in the right direction, such moves are few and far between. These models should be taken up by other agents as well.[19]

The latest accord, the 2015 Paris Agreement, takes a different approach. The 197 signatory countries have promised to limit global temperature increase to just 1.5 °C over pre-industrialization levels, but each country has set its own targets. India, for instance, has promised to cut its emissions intensity (emissions per unit of GDP) by 33-35% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels (Chart 1a/ 1b).[40]

By country

Bangladesh

Climate change in Bangladesh is a critical issue as the country is one of the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.[41][42] In the 2020 edition of Germanwatch's Climate Risk Index, it ranked seventh in the list of countries most affected by climate calamities during the period 1999–2018.[43] Bangladesh's vulnerability to climate change impacts is due to a combination of geographical factors, such as its flat, low-lying, and delta-exposed topography,[44] and socio-economic factors, including its high population density, levels of poverty, and dependence on agriculture.[45]

Factors such as frequent natural disasters, lack of infrastructure, high population density (166 million people living in an area of 147,000 km2 [46]), an extractivist economy and social disparities are increasing the vulnerability of the country in facing the current changing climatic conditions. Almost every year large regions of Bangladesh suffer from more intense events like cyclones, floods and erosion. The mentioned adverse events are slowing the development of the country by bringing socio-economical and environmental systems to almost collapse.[46]

Natural hazards that come from increased rainfall, rising sea levels, and tropical cyclones are expected to increase as the climate changes, each seriously affecting agriculture, water and food security, human health, and shelter.[47] Sea levels in Bangladesh are predicted to rise by up to 0.30 metres by 2050, resulting in the displacement of 0.9 million people, and by up to 0.74 metres by 2100, resulting in the displacement of 2.1 million people.[48]

To address the sea level rise threat in Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 was launched in 2018.[49][50] The government of Bangladesh is working on a range of specific climate change adaptation strategies. Climate Change adaptation plays a crucial role in fostering the country's development. This is already being considered as a synergic urgent action together with other pressing factors such as the permanent threat of shocks – natural, economic or political – the uncertain impact of globalization, and an imbalanced world trade impede higher growth rates.[51]Pakistan

Climate change in Pakistan is expected to cause wide-ranging effects on the environment and people in Pakistan. As a result of ongoing climate change, the climate of Pakistan has become increasingly volatile over the past several decades; this trend is expected to continue into the future. In addition to increased heat, drought and extreme weather conditions in some parts of the country, the melting of glaciers in the Himalayas threatens many of the most important rivers of Pakistan. Between 1999 and 2018, Pakistan was ranked the 5th worst affected country in terms of extreme climate caused by climate change.[52]

Pakistan contributes little to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions at about less than 1%,[53] yet it is very vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Pakistan's lower technical and financial capacity to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change worsen its vulnerability.[54] Food and water security, as well as large displacement of populations are major threats faced by the country.[55] Pakistan's agriculture-dependent economy is especially susceptible to increasing irregularity and uncertainty over climatic conditions. Like many other South Asian nations, Pakistan is faced by high risk due to climate change effects.[56]Nepal

Nepal is one of the most vulnerable countries to the effects of climate change; in the 2020 edition of Germanwatch's Climate Risk Index, it was judged to be the ninth hardest-hit nation by climate calamities during the period 1999 to 2018.[57] Nepal is a least developed country, with 28.6 percent of the population living in multidimensional poverty.[58] Analysis of trends from 1971 to 2014 by the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) shows that the average annual maximum temperature has been increasing by 0.056 °C per year.[59] Precipitation extremes are found to be increasing.[60] A national-level survey on the perception-based survey on climate change reported that locals accurately perceived the shifts in temperature but their perceptions of precipitation change did not converge with the instrumental records.[61] Data reveals that more than 80 percent of property loss due to disasters is attributable to climate hazards, particularly water-related events such as floods, landslides and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs).[62] The floods of 2018 spread across the foothills of the Himalayas and brought landslides have left tens of thousands of houses and vast areas of farmland and roads destroyed.[63] Nepal experienced flash floods and landslides in August, 2018 across the southern border, amounting to US$600 million in damages.[64] There are reports of land once used for growing vegetables has become barren, Yak herders struggles to find grazing patches for their animals. Scientists have found that rising temperatures could spread malaria and dengue to new areas of the Himalayas, where mosquitoes have started to appear in the highlands.[65]

In Nepal, women are also responsible for the traditional daily household chores including food production, household water supply and energy for heating. However, these tasks are likely to become more time-consuming and difficult, as the impacts of climate change increase, if women have to travel farther to collect items. This proves to be an additional stressor for women, increasing their risk to health hazards and illnesses, and in turn increasing their vulnerability to climate change.[66]

See also

References

- Kreft, Sönke; David Eckstein, David; Melchior, Inga (November 2016). Global Climate Risk Index 2017 (PDF). Bonn: Germanwatch e.V. ISBN 978-3-943704-49-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Southern Asia Population, October 2020". worldometer.info. Worldometer. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Ayers, Jessica; Huq, Saleemul; Wright, Helena; Faisal, Arif M.; Hussain, Syed Tanveer (2014-10-02). "Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into development in Bangladesh". Climate and Development. 6 (4): 293–305. doi:10.1080/17565529.2014.977761. ISSN 1756-5529. S2CID 54721256.

- Thomas TS, Mainuddin K, Chiang C, Rahman A, Haque A, Islam N, Quasem S, Sun Y (2013). Agriculture and Adaptation in Bangladesh: Current and Projected Impacts of Climate Change (PDF) (Report). IFPRI. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- IPCC, 2007: Summary for Policymakers. In: Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M.Tignor and H.L. Miller (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. (Hereafter abbreviated to IPCC AR4 – WG1 – SPM) Table SPM-3, page 13.

- Christensen, J.H., B. Hewitson, A. Busuioc, A. Chen, X. Gao, I. Held, R. Jones, R.K. Kolli, W.-T. Kwon, R. Laprise, V. Magaña Rueda, L. Mearns, C.G. Menéndez, J. Räisänen, A. Rinke, A. Sarr and P. Whetton, 2007: Regional Climate Projections. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Archived 2007-12-15 at the Wayback Machine [Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M. Tignor and H.L. Miller (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. (Hereafter abbreviated to IPCC AR4 – WG1 – chapter11) Table 11.1, page 855.

- Rahmstorf, Perrette, Vermeer (2012). "Testing the robustness of semi-empirical sea level projections". Climate Dynamics. 39 (3–4): 861–875. Bibcode:2012ClDy...39..861R. doi:10.1007/s00382-011-1226-7. S2CID 55493326.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Harrabin, Roger (1 February 2007). "How climate change hits India's poor". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- Khan, Sami (2012-01-25). "Effects of Climate Change on Thatta and Badin". Envirocivil.com. Retrieved 2013-10-27.

- Kulp, Scott A.; Strauss, Benjamin H. (29 October 2019). "New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 4844. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.4844K. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12808-z. PMC 6820795. PMID 31664024.

- Rosane, Olivia (October 30, 2019). "300 Million People Worldwide Could Suffer Yearly Flooding by 2050". Ecowatch. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Amos, Jonathan (30 October 2019). "Climate change: Sea level rise to affect 'three times more people'". BBC. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Dasgupta, Saibal (3 February 2007). "Warmer Tibet can see Brahmaputra flood Assam". Times of India. Times Internet Limited. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Aggarwal D, Lal M. "Vulnerability of the Indian coastline to sea level rise" (PDF). SURVAS (Flood Hazard Research Centre). Middlesex University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

- Normile D (May 2000). "Some coral bouncing back from El Niño". Science. 288 (5468): 941–942. doi:10.1126/science.288.5468.941a. PMID 10841705. S2CID 128503395. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

- "Early Warning Signs: Coral Reef Bleaching". Union of Concerned Scientists. 2005. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

- "Bangladesh." MERIC. 18 October 2008. 18 October 2008. <"International". Archived from the original on 2009-05-01. Retrieved 2008-11-03. cty5380.stm>.

- "2018 Was Sixth Warmest Year in India's Recorded History: IMD". The Wire. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- Alexander, Usha. "Ecological Myths, Warming Climates and the End of Nature". The Caravan. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- Rosane, Olivia (June 13, 2019). "36 Die in India Heat Wave, Delhi Records Its Highest All-Time Temperature". Ecowatch. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "New study finds incredibly high carbon pollution costs – especially for the US and India". The Guardian. 1 October 2018.

- Sethi, Nitin (3 February 2007). "Global warming: Mumbai to face the heat". Times of India. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "Meghalaya body's Shylla wary of refugee influx". www.telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- Islam, Md. Nazrul; van Amstel, André, eds. (2018). "Bangladesh I: Climate Change Impacts, Mitigation and Adaptation in Developing Countries". Springer Climate. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-26357-1. ISBN 978-3-319-26355-7. ISSN 2352-0698. S2CID 199493022.

- Ahmed, Ahsan; Koudstall, Rob; Werners, Saskia (2006-10-08). "'Key Risks.' Considering Adaptation to Climate Change Towards a Sustainable Development of Bangladesh". Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- "Bangladesh | FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- "Rice prices and growth, and poverty reduction in Bangladesh" (PDF). FAO. 2020-11-29.

- "Climate change: The big emitters". BBC News. 4 July 2005. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- "Home .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- Ramesha Chandrappa, Sushil Gupta, Umesh Chandra Kulshrestha, Climate Change: Principles and Asian Context, Springer-Verlag, 2011

- UNDP. "India and Climate Change Impacts". Archived from the original on 2011-03-17. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- Badarinath KV, Chand TR, Prasad VK (2006). "Agriculture crop residue burning in the Indo-Gangetic Plains—A study using IRS-P6 AWiFS satellite data" (PDF). Current Science. 91 (8): 1085–1089. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- Lau, WKM (February 20, 2005). "Aerosols may cause anomalies in the Indian monsoon". The Climate and Radiation Branch at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. NASA. Archived from the original (php) on October 1, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- Jana, Jaydev (2003). "Mercury Pollution". Economic and Political Weekly. 38 (33): 3434–3512. JSTOR 4413893.

- Mittal, Radhika (2012). "Climate Change Coverage in Indian Print Media: A Discourse Analysis". The International Journal of Climate Change: Impacts and Responses. 3 (2): 219–230. doi:10.18848/1835-7156/CGP/v03i02/37105. hdl:1959.14/181298.

- Billett, Simon (2010). "Dividing climate change: global warming in the Indian mass media". Climatic Change. 99 (1–2): 1–16. Bibcode:2010ClCh...99....1B. doi:10.1007/s10584-009-9605-3. S2CID 18426714.

- Das, Biswajyoti (2007-08-29). "India tribe to honour Gore on global warming". Reuters. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- Kharmujai RR (3 March 2007). "Wet Desert Of India Drying Out". Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- World carbon dioxide emissions data by country: China speeds ahead of the rest Guardian 31 January 2011

- Padmanabhan, Vishnu (2019-09-01). "The four big climate challenges for India". livemint.com. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

- Kulp, Scott A.; Strauss, Benjamin H. (2019-10-29). "New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 4844. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.4844K. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12808-z. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6820795. PMID 31664024.

- "Report: Flooded Future: Global vulnerability to sea level rise worse than previously understood". climatecentral.org. 2019-10-29. Retrieved 2019-11-03.

- Kreft, Sönke; David Eckstein, David; Melchior, Inga (December 2019). Global Climate Risk Index 2020 (PDF). Bonn: Germanwatch e.V. ISBN 978-3-943704-77-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- Ayers, Jessica; Huq, Saleemul; Wright, Helena; Faisal, Arif M.; Hussain, Syed Tanveer (2014-10-02). "Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into development in Bangladesh". Climate and Development. 6 (4): 293–305. doi:10.1080/17565529.2014.977761. ISSN 1756-5529.

- Thomas TS, Mainuddin K, Chiang C, Rahman A, Haque A, Islam N, Quasem S, Sun Y (2013). Agriculture and Adaptation in Bangladesh: Current and Projected Impacts of Climate Change (PDF) (Report). IFPRI. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- "Bangladesh Population 2018 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan, 2008 (PDF). Ministry of Environment and Forests Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. 2008. ISBN 978-984-8574-25-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2009.

- Davis, Kyle Frankel; Bhattachan, Abinash; D’Odorico, Paolo; Suweis, Samir (2018-06-01). "A universal model for predicting human migration under climate change: examining future sea level rise in Bangladesh". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (6): 064030. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aac4d4. ISSN 1748-9326.

- "Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 | Dutch Water Sector". www.dutchwatersector.com (in Dutch). Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- Bangladesh Delta Plan (BDP) 2100

- "About Bangladesh". UNDP in Bangladesh. Retrieved 2018-07-12.

- Eckstein, David, et al. "Global climate risk index 2020." (PDF) Germanwatch (2019).

- "Pakistan crafts plan to cut carbon emissions 30% by 2025". The Express Tribune. 10 June 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- "Pakistan National Policy on Climate Change". Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2015-05-10.

- Zaheer, Khadija; Colom, Anna. "Pakistan, How the people of Pakistan live with climate change and what communication can do" (PDF). www.bbc.co.uk/climateasia. BBC Media Action.

- Chaudhry, Qamar Uz Zaman (2017-08-24). Climate Change Profile of Pakistan. Asian Development Bank. doi:10.22617/tcs178761. ISBN 978-92-9257-721-6.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO (CC BY 3.0 IGO) license.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO (CC BY 3.0 IGO) license. - "GLOBAL CLIMATE RISK INDEX 2020" (PDF). Germanwatch.

- "Nepal Multidimensional Poverty Index 2018". National Planning Commission.

- "Observed Climate Trend Analysis of Nepal (1971-2014)" (PDF). Department of Hydrology and Meteorology, 2017.

- Karki, Ramchandra; Hasson, Shabeh ul; Schickhoff, Udo; Scholten, Thomas; Böhner, Jürgen (2017). "Rising Precipitation Extremes across Nepal". Climate. 5 (1): 4. doi:10.3390/cli5010004.

- Shrestha, Uttam Babu; Shrestha, Asheshwor Man; Aryal, Suman; Shrestha, Sujata; Gautam, Madhu Sudan; Ojha, Hemant (1 June 2019). "Climate change in Nepal: a comprehensive analysis of instrumental data and people's perceptions". Climatic Change. 154 (3): 315–334. Bibcode:2019ClCh..154..315S. doi:10.1007/s10584-019-02418-5. S2CID 159233373.

- "NEPAL'S NATIONAL ADAPTATION PLAN (NAP) PROCESS: REFLECTING ON LESSONS LEARNED AND THE WAY FORWARD" (PDF). Ministry of Forests and Environment.

- Rebecca Ratcliffe; Arun Budhathoki (14 July 2019). "At least 50 people dead and 1 million affected by floods in South Asia". The Guardian.

- Gill, Peter. "After the Flood: Nepal's Slow Recovery". thediplomat.com.

- Sharma, Bhadra; Schultz, Kai; Conway, Rebecca (2020-04-05). "As Himalayas Warm, Nepal's Climate Migrants Struggle to Survive". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- Sharma, Akriti. "Climate Change Instability and Gender Vulnerability in Nepal: A Case Study on the Himalayan Region" (PDF).

Further reading

- Toman, MA; Chakravorty, U; Gupta, S (2003), India and Global Climate Change: Perspectives on Economics and Policy from a Developing Country, Resources for the Future Press, ISBN 978-1-8918-5361-6.

- "BBC Radio 4 - Costing the Earth, Indian Impact". BBC. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Atlas of India. |

- Climate Change India

- Fighting Global Warming in India

- Global Warming and its effects in South Asian Countries

- General effects overview

- "Country Guide: India". BBC Weather.

- "India—Weather and Climate". High Commission of India, London.

- Maps, imagery, and statistics

- "India Meteorological Department". Government of India.

- "Weather Resource System for India". National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 2007-04-29.

- Forecasts

- "India: Current Weather Conditions". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Archived from the original on 2007-04-25.