Turkmens

Turkmens (Turkmen: Türkmenler, Түркменлер, توركمنلر, [tʏɾkmønˈløɾ];[10] historically the Turkmen), also known as Turkmen Turks (Turkmen: Türkmen türkleri, توركمن تورکلری),[11][12][13] are a Turkic ethnic group native to Central Asia, living mainly in Turkmenistan, northern and northeastern regions of Iran and Afghanistan. Sizeable groups of Turkmens are found also in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and the North Caucasus (Stavropol Krai). They speak the Turkmen language, which is classified as a part of the Eastern Oghuz branch of the Turkic languages. Examples of other Oghuz languages are Turkish, Azerbaijani, Qashqai, Gagauz, Khorasani, and Salar.[14]

TürkmenlerТүркменлерتوركمنلر | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Turkmens in folk costume at the 20th Independence Day parade, 27 September 2011 | |

| Total population | |

| c. 6.4 million[a] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 4,948,000[1] | |

| 1,100,000[2][3] | |

| 790,000[4] | |

| 152,000[5] | |

| 46,885[6] | |

| 15,171[7] | |

| 7,709[8] | |

| 6,000[9] | |

| 5,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Turkmen | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Oghuz Turks | |

a. ^ The total figure is merely an estimation; a sum of all the referenced populations. | |

In the early Middle ages, Turkmens called themselves Oghuz, and in the Middle Ages they took the ethnonym - Turkmen.[15] In Byzantine, then in the European sources, and later in the American tradition, Turkmens were called Turkomans,[16][17][18][19] in the countries of the Near and Middle East - Turkmens, as well as Torkaman, Terekeme; in Kievan Rus - Torkmens;[20] in the Duchy of Moscow - Taurmen;[21] and in the Tsarist Russia - Turkoman and Trukhmen.[22]

Seljuks, Khwarazmians, Qara Qoyunlu, Aq Qoyunlu, Ottomans and Afsharids are also believed to descend from the Turkmen tribes of Qiniq, Begdili, Yiva, Bayandur, Kayi and Afshar respectively.[23]

Etymology

The term Turkmen is generally applied to the Turkic tribes that have been distributed across the Near and Middle East, as well as Central Asia, from the 11th century to modern times.[24] Originally, all Turkic tribes who belonged to the Turkic dynastic mythological system and/or converted to Islam (e.g. Karluks, Oghuz Turks, Khalajes, Kanglys, Kipchaks, etc.) were designated "Turkmens".[25][26] Only later did this word come to refer to a specific ethnonym. The current majority view for the etymology of the name is that it comes from Türk and the Turkic emphasizing suffix -men, meaning "'most Turkish of the Turks' or 'pure-blooded Turks.'"[27] A folk etymology, dating back to the Middle Ages and found in al-Biruni and Mahmud al-Kashgari, instead derives the suffix -men from the Persian suffix -mānind, with the resulting word meaning "like a Turk". While formerly the dominant etymology in modern scholarship, this mixed Turkic-Persian derivation is now viewed as incorrect.[28]

Today the terms are usually restricted to two Turkic groups: the Turkmen people of Turkmenistan and adjacent parts of Central Asia, and the Turkomans of Iraq and Syria.

Origins

Türkmens were mentioned near the end of the 10th century A.D in Islamic literature by the Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi in Ahsan Al-Taqasim Fi Ma'rifat Al-Aqalim.[29] In his work, which was completed in 987 A.D, al-Muqaddasi writes about Turkmens twice while depicting the region as the frontier of the Muslim possessions in Central Asia.[30]

Earlier references to Türkmen might be trwkkmˀn (if not trkwmˀn "translator"), mentioned in an 8th-century Sogdian letter and 特拘夢 Tejumeng (< MC ZS *dək̚-kɨo-mɨuŋH), another name of Sogdia, besides Suyi 粟弋 and Sute 粟特, according to the Chinese encyclopedia Tongdian.[31][32] However, even if 特拘夢 might have transcribed Türkmen, these "Türkmens" might be Karluks instead of modern Türkmens' Oghuz-speaking ancestors.[33] Zuev (1960) links the tribal name 餘沒渾 Yumeihun (< MC *iʷо-muət-хuən) in Tang Huiyao to the name Yomut of a modern Turkmen clan.[34][35]

Towards the end of the 11th century, in Divânü Lügat'it-Türk (Compendium of the Turkic Dialects), Mahmud Kashgari uses “Türkmen” synonymously with “Oğuz”.[36] He describes Oghuz as a Turkic tribe and says that Oghuz and Karluks were both known as Turkmens.[37][38]

The modern Turkmen people descend from the Oghuz Turks of Transoxiana, the western portion of Turkestan, a region that largely corresponds to much of Central Asia as far east as Xinjiang. Famous historian and ruler of Khorezm of the XVII century Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur links the origin of all Turkmens to 24 Oghuz tribes in his literary work "Genealogy of the Turkmens".[39]

In the 7th century AD, Oghuz tribes had moved westward from the Altay mountains through the Siberian steppes, and settled in this region. They also penetrated as far west as the Volga basin and the Balkans. These early Turkmens are believed to have mixed with native Sogdian peoples and lived as pastoral nomads until being conquered by the Russians in the 19th century.[40]

Migration of the Turkmen tribes from the territory of Turkmenistan and the rest of Central Asia in the south-west direction began mainly from the 11th century and continued until the 18th century. These Turkmen tribes played a significant role in the ethnic formation of such peoples as Turks, Turkmens of Iraq and Syria, as well as the Turkic population of Iran and Azerbaijan.[41][42][43] To preserve their independence, those tribes that remained in Turkmenistan were united in military alliances, although remnants of tribal relations remained until the 20th century. Their traditional occupations were farming, cattle breeding, and various crafts. Ancient samples of applied art (primarily carpets and jewelry) indicate a high level of folk art culture.

Genetics

Haplogroup Q-M242 is commonly found in Siberia, Southeast Asia, Central Asia. This haplogroup forms a large percentage of the paternal lineages of Turkmens.

Grugni et al. (2012) found Q-M242 in 42.6% (29/68) of a sample of Turkmens from Golestan, Iran.[44] Di Cristofaro et al. (2013) found Q-M25 in 31.1% (23/74) and Q-M346 in 2.7% (2/74) for a total of 33.8% (25/74) Q-M242 in a sample of Turkmens from Jawzjan.[45] Karafet et al. (2018) found Q-M25 in 50.0% (22/44) of another sample of Turkmens from Turkmenistan.[46] Haplogroup Q have seen its highest frequencies in the Turkmens from Karakalpakstan (mainly Yomut) at 73%.[47]

A genetic study on the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups of a Turkmen sample describes a mixture of mostly West Eurasian lineages and minority of East Eurasian lineages. Turkmens also have two unusual mtDNA markers with polymorphic characteristics, only found in Turkmens and southern Siberians.[48]

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Turkmenistan |

|

| Periods |

| Related historical names of the region |

|

|

Turkmens belong to the Oghuz tribes, who originated on the periphery of Central Asia and founded gigantic empires beginning from the 3rd millennium BC. Subsequently, Turkmen tribes founded lasting dynasties in Central Asia, Middle East, Persia and Anatolia that had a profound influence on the course of history of those regions.[49] The most prominent of those dynasties were the Ghaznavids, Seljuks, Ottomans, Safavids, Afsharids and Qajars. Representatives of the Turkmen tribes of Ive and Bayandur were also the founders of the short-lived, but formidable states of Kara Koyunlu and Ak Koyunlu Turkmens respectively.[50][51]

Turkmens that stayed in Central Asia largely survived unaffected by the Mongol period due to their semi-nomadic lifestyle and became traders along the Caspian, which led to contacts with Eastern Europe. Following the decline of the Mongols, Tamerlane conquered the area and his Timurid Empire would rule, until it too fractured, as the Safavids, Khanate of Bukhara, and Khanate of Khiva all contested the area. The expanding Russian Empire took notice of Turkmenistan's extensive cotton industry, during the reign of Peter the Great, and invaded the area. Following the decisive Battle of Geok Tepe in January 1881, the bulk of Turkmen tribes found themselves under the rule of the Russian Emperor, which was formalized in the Akhal Treaty between Russia and Persia. After the Russian Revolution, Soviet control was established by 1921, and in 1924 Turkmenistan became the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic. Turkmenistan gained independence in 1991.

Culture and society

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of Turkmenistan |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

Turkmenistan portal |

Religion

The Turkmen of Turkmenistan, like their kin in Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Iran, are predominantly Muslims. According to the CIA World Factbook, Turkmenistan is 89% Muslim and 10% Eastern Orthodox. Most ethnic Russians and Armenians are Orthodox Christians. The remaining 1% is unknown. A 2009 Pew Research Center report indicates a higher percentage of Muslims with 93.1% of Turkmenistan's population adhering to Islam. The great majority of Turkmen readily identify themselves as Muslims and acknowledge Islam as an integral part of their cultural heritage. However, there are some who support a revival of the religion's status merely as an element of national identity.

Language

Turkmen (Latin: Türkmençe, Cyrillic: Түркменче) is the language of the nation of Turkmenistan. It is spoken by over 5,200,000 people in Turkmenistan, and by roughly 3,000,000 people in other countries, including Iran, Afghanistan, and Russia.[52] Up to 30% of native speakers in Turkmenistan also claim a good knowledge of Russian, a legacy of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union.

The Turkmen language is closely related to Azerbaijani, Turkish, Gagauz, Qashqai and Crimean Tatar, sharing common linguistic features with each of those languages. There is a high degree of mutual intelligibility between these languages.[53][54] A handful of specific lexical and grammatical differences formed within the Turkmen language as spoken in Turkmenistan, Iran and Afghanistan, after more than a century of separation between the people speaking the language; mutually intelligibility, however, has been preserved.

Turkmen is not a literary language in Iran and Afghanistan, where many Turkmen tend towards bilingualism, usually conversant in the countries' different dialects of Persian, such as Dari and Tajik in Afghanistan. Variations of the Persian alphabet are, however, used in Iran.

Literature

Turkmen literature comprises oral compositions and written texts in old Oghuz Turkic and Turkmen languages. Turkmens have joint claims to a great number of literary works written in Old Oghuz Turkic and Persian (by Seljuks in 11-12th centuries) languages with other people of the Oghuz Turkic origin, mainly of Azerbaijan and Turkey. This works include, but are not limited to the Book of Dede Korkut, Gorogly and others.[55] The medieval Turkmen literature was heavily influenced by Arabic and Persian, and used mostly Arabic alphabet.[56]

There is general consensus, however, that distinctively Turkmen literature originated in 18th century with the poetry of Magtymguly Pyragy, who is considered the father of the Turkmen literature.[57][58] Other prominent Turkmen poets of that era are Döwletmämmet Azady (Magtymguly's father), Nurmuhammet Andalyp, Abdylla Şabende, Şeýdaýy, Mahmyt Gaýyby and Gurbanaly Magrupy.[59]

In the 20th century, Turkmenistan's most prominent Turkmen-language writer was Berdi Kerbabayev, whose novel Decisive Step, later made into a motion picture directed by Alty Garlyyev, is considered the apotheosis of modern Turkmen fiction. It earned him the USSR State Prize for Literature in 1948.[60]

Music

The musical art of the Turkmens is an integral part of the musical art of the Turkic peoples. The music of the Turkmen people is closely related to the Kyrgyz and Kazakh folk forms. Important musical traditions include traveling singers called bakshy, who sing with instruments such as the two-stringed lute called dutar.

Other important musical instruments are gopuz, tüydük, dombura, and gyjak. The most famous Turkmen bakshys are those who lived in the 19th century: Amangeldi Gönübek, Gulgeldi ussa, Garadali Gokleng, Yegen Oraz bakshy, Hajygolak, Nobatnyyaz bakshy, Oglan bakshy, Durdy bakshy, Shukur bakshy, Chowdur bakshy and others. Usually they narrated the woeful and gloomy events of the Turkmen history through their music. The names and music of these bakshys have become legendary among the Turkmen people, and passed orally from generation to generation.[61]

The Central Asian classical music tradition muqam is also present in Turkmenistan.[62]

Cuisine

Characteristics of traditional Turkmen cuisine are rooted in the largely nomadic nature of day-to-day life prior to the Soviet period coupled with a long local tradition, dating back millennia before the arrival of the Turkmen in the region, of white wheat production. Baked goods, especially flat bread (Turkmen: çörek) typically baked in a tandoor, make up a large proportion of the daily diet, along with cracked wheat porridge (Turkmen: ýarma), wheat puffs (Turkmen: pişme), and dumplings (Turkmen: börek). Since sheep-, goat-, and camel husbandry are traditional mainstays of nomadic Turkmen, mutton, goat meat, and camel meat were most commonly eaten, variously ground and stuffed in dumplings, boiled in soup, or grilled on spits in chunks (Turkmen: şaşlyk) or as fingers of ground, spiced meat (Turkmen: kebap). Rice for plov was reserved for festive occasions. Due to lack of refrigeration in nomad camps, dairy products from sheep-, goat-, and camel milk were fermented to keep them from spoiling quickly. Fish consumption was largely limited to tribes inhabiting the Caspian Sea shoreline. Fruits and vegetables were scarce, and in nomad camps limited mainly to carrots, squash, pumpkin, and onions. Inhabitants of oases enjoyed more varied diets, with access to pomegranate-, fig-, and stone fruit orchards; vineyards; and of course melons. Areas with cotton production could use cottonseed oil and sheep herders used fat from the fat-tailed sheep. The major traditional imported product was tea.[63][64][65]

The Royal Geographic Society reported in 1882,

The food of the Tekkes [sic] consists of well-prepared pillaus and of game; also of fermented camels' milk, melons, and water-melons. They use their fingers in conveying food to their mouths, but guests are provided with spoons.[66]

In sharp contrast to other Central Asian and Turkic ethnic groups, Turkmen do not eat horse meat, and in fact eating of horse meat is prohibited by law in Turkmenistan.[67][68]

Conquest by the Russian Empire in the 1880s introduced new foods, including such meats as beef, pork, and chicken, as well as potatoes, tomatoes, cabbage, and cucumbers, though they did not find widespread use in most Turkmen households until the Soviet period. While now consumed widely, they are, strictly speaking, not considered "traditional".[64][69]

Nomadic heritage

.jpg.webp)

Before the establishment of Soviet power in Central Asia, it was difficult to identify distinct ethnic groups in the region. Sub-ethnic and supra-ethnic loyalties were more important to people than ethnicity. When asked to identify themselves, most Central Asians would name their kin group, neighborhood, village, religion or the state in which they lived; the idea that a state should exist to serve an ethnic group was unknown. That said, most Turkmen could identify the tribe to which they belonged, though they might not identify themselves as Turkmen.[70]

Most Turkmen were nomads until the 19th century when they began to settle the area south of the Amu Darya. Many Turkmen became semi-nomadic, herding sheep and camels during spring, summer, and fall, but planting crops, wintering in oasis camps, and harvesting the crops in the summer and autumn. As a rule they did not settle in cities and towns until the advent of the Soviet government. This mobile lifestyle precluded identification with anyone outside one's kin group and led to frequent conflicts between different Turkmen tribes, particularly regarding access to water.

In collaboration with the local nationalists, the Soviet government sought to transform the Turkmen and other similar ethnic groups in the USSR into modern socialist nations that based their identity on a fixed territory and a common language. Prior to the Battle of Geok Tepe in January 1881 and subsequent conquest of Merv in 1884, the Turkmen "retained the condition of predatory, horse-riding nomads, who were greatly feared by their neighbours as 'man-stealing Turks.' Until subjugated by the Russians, the Turkmens were a warlike people, who conquered their neighbours and regularly captured ethnic Persians for sale as slaves in Khiva. It was their boast that not one Persian had crossed their frontier except with a rope round his neck."[71]

The Soviet-led standardization of the Turkmen language, education, and projects to promote ethnic Turkmen in industry, government and higher education led growing numbers of Turkmen to identify with a larger national Turkmen culture rather than with sub-national, pre-modern forms of identity.[72] After gaining independence from the Soviet Union, Turkmen historians went to great lengths to prove that the Turkmen had inhabited their current territory since time immemorial; some historians even tried to deny the nomadic heritage of the Turkmen.[73]

Turkmen lifestyle was heavily invested in horsemanship and as a prominent horse culture, Turkmen horse-breeding was an ages old tradition. Before the Soviet era, a proverb stated that the Turkmen's home was where his horse happened to stand. In spite of changes prompted during the Soviet period, the Ahal Teke tribe in southern Turkmenistan has remained very well known for its horses, the Akhal-Teke desert horse – and the horse breeding tradition has returned to its previous prominence in recent years.[74]

Many tribal customs still survive among modern Turkmen. Unique to Turkmen culture is kalim which is a groom's "dowry", that can be quite expensive and often results in the widely practiced tradition of bridal kidnapping.[75] In something of a modern parallel, in 2001, President Saparmurat Niyazov had introduced a state enforced "kalim", which required all foreigners who wanted to marry a Turkmen woman to pay a sum of no less than $50,000.[76] The law was repealed in March 2005.[77]

Other customs include the consultation of tribal elders, whose advice is often eagerly sought and respected. Many Turkmen still live in extended families where various generations can be found under the same roof, especially in rural areas.[75]

The music of the nomadic and rural Turkmen people reflects rich oral traditions, where epics such as Koroglu are usually sung by itinerant bards. These itinerant singers are called bakshy and sing either a cappella or with instruments such as the dutar, a two-stringed lute.

Society today

Since Turkmenistan's independence in 1991, a cultural revival has taken place with the return of a moderate form of Islam and celebration of Novruz, the Persian New Year marking the onset of spring.

Turkmen can be divided into various social classes including the urban intelligentsia and workers whose role in society is different from that of the rural peasantry. Secularism and atheism remain prominent for many Turkmen intellectuals who favor moderate social changes and often view extreme religiosity and cultural revival with some measure of distrust.[78]

The five traditional carpet rosettes, called göl in Turkmen, that form motifs in the country's state emblem and flag represent the five major Turkmen tribes.

Sport

Sports have historically been an important part of Turkmen life. Such sports as horseback riding and Goresh have been praised in Turkmen literature. During the Soviet era, Turkmen athletes competed in numerous competitions, including Olympic games as part of the Soviet Union team and, in 1992, as part of the Unified Team.[81]

After Turkmenistan gained her independence, new ways of establishing physical and sports movements in the country began to emerge. To implement a new sports policy, new multi-purpose stadiums, physical education and health complexes, sports schools and facilities were built in all regions of the country. Turkmenistan also has a modern Olympic village which hosted 2017 Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games, and is unparalleled in Central Asia.

Turkmenistan supports the country's sports movements and encourages sports on a state level. While football remains the most popular sport, such sports as Turkmen goresh, horseback riding and lately ice hockey are also very popular among Turkmens.[82]

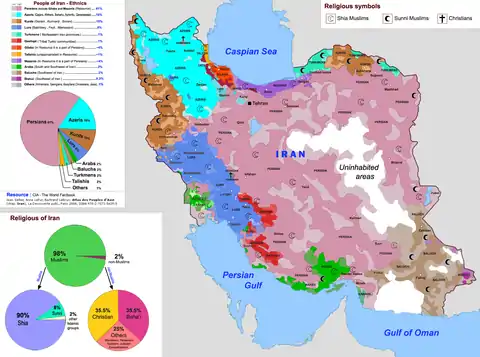

Turkmens in Iran

Iranian Turkmens are a branch of Turkmen people who live mainly in northern and northeastern regions of Iran. Their region is called Turkmen Sahra and includes substantial parts of Golestan province. Representatives of such contemporary Turkmen tribes as Yomut, Goklen, Īgdīr, Saryk, Salar and Teke have lived in Iran since the 16th century,[83] though ethnic history of Turkmens in Iran starts with the Seljuk conquest of the region in the 11th century.[84]

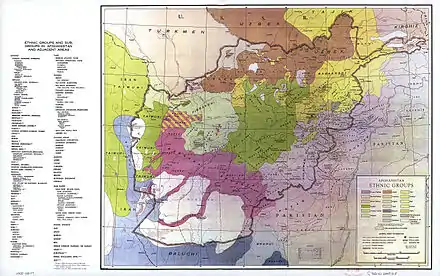

Turkmens in Afghanistan

The Afghan Turkmen population in the 1990s was estimated at around 200,000. The original Turkmen groups came from east of the Caspian Sea into northwestern Afghanistan at various periods, particularly after the end of the 19th century when the Russians moved into their territory. They established settlements from Balkh Province to Herat Province, where they are now concentrated; smaller groups settled in Kunduz Province. Others came in considerable numbers as a result of the failure of the Basmachi revolts against the Bolsheviks in the 1920s.[85] Turkmen tribes, of which there are twelve major groups in Afghanistan, base their structure on genealogies traced through the male line. Senior members wield considerable authority. Formerly a nomadic and warlike people feared for their lightning raids on caravans, Turkmen in Afghanistan are farmer-herdsmen and important contributors to the economy. They brought karakul sheep to Afghanistan and are also renowned makers of carpets, which, with karakul pelts, are major hard currency export commodities. Turkmen jewelry is also highly prized.[85]

Turkmens of Stavropol krai' of Russia

In the Stavropol Krai of southern Russia, there is a long established colony of Turkmen. They are often referred to as Trukhmen by the local ethnic Russian population, and sometimes use the self-designation Turkpen.[86] According to the 2010 Census of Russia, they numbered 15,048, and accounted for 0.5% of the total population of Stavropol Krai.

The Turkmens are said to have migrated into the Caucasus in the 17th century, in particular in the Mangyshlak region. These migrants belonged mainly to the Chowdur (Russian variants Chaudorov, Chavodur), Sonchadj and Ikdir tribes. The early settlers were nomadic but over time became sedentary. In their cultural life the Trukhmens of today differ very little from their neighbours and are now settled farmers and stockbreeders.[86]

Although the Turkmen language belongs to the Oghuz group of Turkic languages, in Stavropol it has been strongly influenced by the Nogai language, which belongs to the Kipchak group. The phonetic system, grammatical structure and to some extent also the vocabulary have been somewhat influenced.[87]

Demographics and population distribution

In 1911, the population of Turkmens in the Russian Empire was estimated to be 290,170, and it was "conjectured that their total number [in all countries] does not exceed 350,000".[71]

Today the Turkmen people of Central Asia and near neighbors live in:

- Turkmenistan, where some 85% of the population of 5,042,920 people (July 2006 est.) are ethnic Turkmen. In addition, an estimated 1,200 Turkmen refugees from northern Afghanistan currently reside in Turkmenistan due to the ravages of the Soviet–Afghan War and factional fighting in Afghanistan which saw the rise and fall of the Taliban.[88]

- Afghanistan, where as of 2006, 200,000 ethnic Turkmen are concentrated primarily along the Turkmen-Afghan border in the provinces of Faryab, Jowzjan, Samangan and Baghlan. There are also communities in Balkh and Kunduz Provinces.

- Iran, where about 719,000 Turkmen are primarily concentrated in the provinces of Golestān and North Khorasan.[4]

References

- "The World Factbook". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Ethnic Groups". Library of Congress Country Studies. 1997. Retrieved 2010-10-08. ^ Jump up to: a b

- https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/ethnic-groups-of-afghanistan.html

- "Ethnologue". Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- Alisher Ilhamov (2002). Ethnic Atlas of Uzbekistan. Open Society Institute: Tashkent.

- 2002 Russian census

- 2002 Tajikistani census (2010)

- "About number and composition population of Ukraine by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". Ukraine Census 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20060321181818/http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/home/opendoc.pdf?tbl=SUBSITES&page=SUBSITES&id=434fdc702. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-03-21. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Clark, Larry (1998). Turkmen Reference Grammar. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Mehmet Kara, Türkmen Türkleri Edebiyatı (The Literature of the Turkmen Turks), Türk Dünyası El Kitabı, Türk Kültürünü Araştırma Enstitüsü Yayınları, Ankara 1998, pp. 5-17

- Gokchur, Engin (2015). "Upon Common Word Existance of Turkmen Turkish and Turkey's Turkish Dialects". The Journal of International Social Research. 8 (36): 135.

- "Türkmenistan, kardeş ülke (Turkmenistan, brotherly nation)". Türkiye gazetesi.

- "UCLA Language Materials Project: Main". Archived from the original on 20 July 2006. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Hamadani, Rashid-al-Din (1939) [1858]. "Legends of Oghuz Khan. Tribal division of the Turkmens (Extracts from Jami' al-Tawarikh)". USSR Academy of Sciences.

These tribes in the course of time divided into many branches, at each time (other) branches appeared from each branch; each got a name and nickname for some reason or on some occasion: the Oghuzes, who are now all called Turkmens and who branched out into Kipchaks, Kalachs (Khalajs), Kangly, Karluks and other branches belonging to them...

- D. Yeremeyev. Ethnogenesis of the Turks. M. Nauka (Science), 1971. - “At the end of the XI century, for the first time in the Byzantine chronicles, Turkmens that penetrated Asia Minor are mentioned. Anna Komnene calls them Turkomans.”

- Peter Hopkirk (1994). The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia. ISBN 9781568360225.

- Arminius Vambery, "The Turcomans Between the Caspian and Merv", The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 9. (1880)

- Merriam-Webster. "Turkoman".

Turkoman: a member of a Turkic-speaking, traditionally nomadic people living chiefly in Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Iran

- Нестор-летописец (Nestor the Chronicler). Повесть временных лет (Primary Chronicle). - «Вышли они из пустыни Етривской между востоком и севером, вышло же их 4 колена: торкмены и печенеги, торки, половцы.» (They came out of the Etriva desert between east and north, but their 4 tribes came out: Torkmens and Pechenegs, Torks, Polovtsians.)

- "Летописные повести о монголо-татарском нашествии" [Chronicles about Mongol-Tatar Invasion] (in Russian).

In the same year, nations came, about which no one knows exactly who they are, and where they came from, and what their language is, and what kind of tribe they are, and what faith. And they call them Tatars, and some say - Taurmen, and others - Pechenegs.

- "О торгах на Каспийском море древних, средних и новейших времен" [On Trade in the Caspian Sea in Ancient, Middle and Modern Times] (in Russian). Moscow: Moscow Soymonov Journal. 1785.

Since ancient times, Russians and Tatars used to travel from Astrakhan in companies on small ships and there they had trade with the Trukhmens or Turkomans

- "Abu'l Ghazi Bahadur "The Genealogy of the Turkmens" (in Russian)". Russian State Library.

- Barbara Kellner-Heinkele, "Türkmen", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, eds. P.J. Bearman, T.H. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. Van Donzel and W. P. Heinrichs, vol. X (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2000), pp. 682-685

- Hamadani, Rashid-al-Din (1952). "Джами ат-Таварих (Jami' al-tawarikh)". USSR Academy of Sciences.

- Golden, Peter (1992). An introduction to the history of the Turkic peoples : ethnogenesis and state-formation in the medieval and early modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Harrassowitz. pp. 211–213.

- Clark, Larry (1996). Turkmen Reference Grammar. Harrassowitz. p. 4., Annanepesov, M. (1999). "The Turkmens". In Dani, Ahmad Hasan (ed.). History of civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 127., Golden, Peter (1992). An introduction to the history of the Turkic peoples : ethnogenesis and state-formation in the medieval and early modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Harrassowitz. pp. 213–214..

- Clark, Larry (1996). Turkmen Reference Grammar. Harrassowitz. p. 4.,Annanepesov, M. (1999). "The Turkmens". In Dani, Ahmad Hasan (ed.). History of civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 127.,Golden, Peter (1992). An introduction to the history of the Turkic peoples : ethnogenesis and state-formation in the medieval and early modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Harrassowitz. pp. 213–214..

- Al-Marwazī, Sharaf Al-Zämān Tāhir Marvazī on China, the Turks and India, Arabic text (circa A.D. 1120) (English translation and commentary by V. Minorsky) (London: The Royal Asiatic Society, 1942), p. 94

- V. Minorsky, “Commentary,” in Sharaf Al-Zämān Tāhir Marvazī on China, the Turks and India, Arabic text (circa A.D. 1120) (English translation and commentary by V. Minorsky) (London: The Royal Asiatic Society, 1942), p. 94.

- Golden, Peter B. (1992) An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. p. 212-3

- Du You, Tongdian vol. 193 "粟弋,後魏通焉。在蔥嶺西,大國。一名粟特,一名特拘夢。" Tr. "Suyi, Latter Wei [knew it] thoroughly. It is a large country to the west of Onion Ridges. Another name is Sute; another name is Tejumeng"

- Kafesoğlu, İbrahim. (1958) “Türkmen Adı, Manası ve Mahiyeti,” in Jean Deny Armağanı: Mélanges Jean Deny, eds., János Eckmann, Agâh Sırrı Levend and Mecdut Mansuroğlu (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi) p. 131

- Tang Huiyao vol. 72 txt. "餘沒渾馬。與迴紇相類。印州。赤馬。與迴紇苾餘沒渾同類。印行。" tr. "Horses of the Yumeihun and horses of the Uyghurs are of similar stock; tamga 州. Horses of the Chiks, and of the Uyghurs, of the (Qi)bis', and of the Yumeihun, are of the same stock; tamga 行"

- Zuev Yu.A. (1960). "Tamgas, Horses from the Vassal Princedoms" in Works of History, Archeology, and Ethnography Institute 8, p. 112-113, 128

- Kaşgarlı Mahmud, Divânü Lügat'it-Türk, vol. I, p. 55.

- Kaşgarlı Mahmud, Divânü Lügat'it-Türk,vol. I, pp. 55-58;

- A. Zeki Velidî Togan, Oğuz Destanı: Reşideddin Oğuznâmesi, Tercüme ve Tahlili (İstanbul: Enderun Kitabevi, 1982), pp. 50-52

- Kononov А. Н. (1958). "Genealogy of the Turkmens. Introduction (in Russian)". M. AS USSR.

- Bacon, Elizabeth Emaline (1966). Amazon.com: Central Asians under Russian Rule: A Study in Culture Change (Cornell Paperbacks): Elizabeth E. Bacon, Michael M. J. Fischer: Books. ISBN 9780801492112.

- "Turks (in Russian)". Big Soviet Encyclopedia.

Ethnically, T. consisted of two main components: the Turkic nomadic tribes (mainly Oghuzes and Turkmens), who migrated to Asia Minor from Central Asia and Iran in the 11–13 centuries (during the Mongol and Seljuk conquests (see. Seljuks)), and local population of Asia Minor.

- Ármin Vámbéry (2003). "Traveling to Central Asia". Eastern Literature.

Turkmens greatly contributed to the Turkification of the northern regions of Persia, especially during the Atabeg rule in Iran. Most of the Turkic population of Transcaucasia, Azerbaijan, Mazenderan and Shiraz are undoubtedly of Turkmen origin.

- "Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary". 1907–1909.

Azerbaijan or Azerbeijan (ancient Atropatena), north. west. province of Persia, on the Russian border, on the Armenian mountain elevation, 104 t. km., about 1 mill. p. (Armenians, Turkmens, Kurds). Main products: cotton, dried fruits, salt. Chief city - Tabriz.

- Grugni, Viola; et al. (2012). "Ancient Migratory Events in the Middle East: New Clues from the Y-Chromosome Variation of Modern Iranians". PLOS ONE. 7 (7): e41252. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...741252G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041252. PMC 3399854. PMID 22815981.

- Di Cristofaro, J; Pennarun, E; Mazières, S; Myres, NM; Lin, AA; et al. (2013). "Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e76748. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...876748D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076748. PMC 3799995. PMID 24204668.

- Tatiana M. Karafet, Ludmila P. Osipova, Olga V. Savina, et al. (2018), "Siberian genetic diversity reveals complex origins of the Samoyedic-speaking populations." Am J Hum Biol. 2018;e23194. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23194. DOI: 10.1002/ajhb.23194.

- Skhalyakho, Rosa; Zhabagin, Maxat; M. Yusupov, Yu; Agdzhoyan, Anastasiya (2016). "Gene pool of Turkmens from Karakalpakstan in their Central Asian context (Y-chromosome polymorphism)". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Malyarchuk, B. A.; Derenko, M. V.; Denisova, G. A.; Nassiri, M. R.; Rogaev, E. I. (1 April 2002). "Mitochondrial DNA Polymorphism in Populations of the Caspian Region and Southeastern Europe". Russian Journal of Genetics. 38 (4): 434–438. doi:10.1023/A:1015262522048. S2CID 19409969. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- Stefano Carboni, Jean-François de Lapérouse, Historical overview - "Turkmen Jewelry: Silver Ornaments from the Marshall and Marilyn R. Wolf Collection", published by Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011

- Safa, Z. (1986). PERSIAN LITERATURE IN THE TIMURID AND TÜRKMEN PERIODS (782–907/1380–1501). In P. Jackson & L. Lockhart (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Iran (The Cambridge History of Iran, pp. 913-928). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- « The Timurid and Turkmen Dynasties of Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia », in : David J. Roxburgh, ed., The Turks: A Journey of Thousand Years, 600-1600. London, Royal Academy of Arts, 2005, pp. 192-200

- "Turkmen". Ethnologue. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Aspects of Altaic Civilization III: Proceedings of the Thirtieth Meeting of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, June 19-25, 1987. Psychology Press. 1996-12-13. ISBN 9780700703807.

- "Language Materials Project: Turkish". UCLA International Institute, Center for World Languages. February 2007

- Akatov, Bayram (2010). Ancient Turkmen Literature, the Middle Ages (X-XVII centuries) (in Turkmen). Turkmenabat: Turkmen State Pedagogical Insitute, Ministry of Education of Turkmenistan. pp. 29, 39, 198, 231.

- Babyr (2004). Diwan. Ashgabat: Miras. p. 7.

- "Turkmenistan Culture". Asian recipe.

- Levin, Theodore; Daukeyeva, Saida; Kochumkulova, Elmira (2016). Music of Central Asia. Indiana University press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-253-01751-2.

- "Nurmuhammet Andalyp". Dunya Turkmenleri.

- Каррыев, Клыч Мурад (1966). "КЕРБАБА́ЕВ, Берды". In Сурков, Алексей (ed.). Краткая литературная энциклопедия. 3. Moscow: «Советская энциклопедия». Archived from the original on 2015-01-08.

- Weyisova, Ayjemal. "Sungatyň sarpasy (Respect to the Art)". Zaman Turkmenistan.

- Багдасаров, A.; Ванукевич, A.; Худайшукуров, T. (1981). Туркменская кулинария (in Russian). Ашхабад: Издательство "Туркменистан".

- Turkmen dastarkhan. 1. Ashgabat: Turkmen State Publishing Service. 2014.

- Turkmen dastarkhan. 2. Ashgabat: Turkmen State Publishing Service. 2014.

- Cumming, Sir Duncan, ed. (1977). "Chapter 13 The new Russian-Persian Frontier East of the Caspian Sea". Country of the Turkomans. London: Oguz Press and the Royal Geographic Society. p. 184.

- Patten, Fred (19 April 2013). "Profile: Turkmenistan - The Land of Horse Heaven".

- Kjuka, Deana (11 April 2013). "Turkmenistan: A Land Of Health And Happiness...And Horses". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- Goldstein, Darra (2006). "Turkmenistan on a Plate". 57 (1). Saudi Aramco World. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Adrienne Lynn Edgar (2007). Tribal Nation: The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9781400844296.

- Turanians and Pan-Turanianism. London: Naval Staff Intelligence Department. November 1918.

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2007). Tribal Nation: The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton University Press. p. 261. ISBN 9781400844296.

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2007). Tribal Nation: The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton University Press. p. 264. ISBN 9781400844296.

- "Turkmenistan Embassy Washington". www.turkmenistanembassy.org. Archived from the original on 2010-11-15. Retrieved 2006-05-17.

- "Turkmen Society". Archived from the original on 2007-03-18.

- Sherwell, Philip (July 22, 2001). "Price of loving a Turkmen girl is now $50,000". Daily Telegraph.

- Saidazimova, Gulnoza (June 10, 2005). "Turkmenistan: Marriage Gets Cheaper As Turkmenbashi Drops $50,000 Dollar Foreigners' Fee". Radio Free Europe.

- "US Library of Congress Country Studies-Turkmenistan: Social Structure". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Official website of "Rubin" Kazan Football Club (in Russian)". Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- Airat Nigmatullin; Dzhaudat Abdulin; Rashid Galiamov. (17 December 2012). "Kurban Berdiyev's interview, Part 2 (in Russian)". БИЗНЕС Online. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- "Turkmenistan". International Olympic Committee.

- "The national ice hockey team of Turkmenistan finished the 2019 World Cup in Sofia in third place". Turkmenportal.

- Logashova B.R. Turkmens of Iran (historical and ethnographic study), published by "Nauka" (Science); 1976. p.14

- P. Golden. The Turkic peoples and Caucasia, Transcaucasia, Nationalism and Social Change: Essays in the History of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, ed. by Ronald G. Suny; Michigan, 1996. pp. 45-67

- "US Library of Congress Country Studies-Afghanistan: Turkmen".

- The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire. Eki.ee. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2013-07-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "UNHCR Begins Compiling Database of Refugees in Turkmenistan". Archived from the original on 2005-12-08.

Sources

- Bacon, Elizabeth E. Central Asians Under Russian Rule: A Study in Culture Change, Cornell University Press (1980). ISBN 0-8014-9211-4.

- Turkmenistan Pages by Ekahau

- Did the engsi hang inside or outside the yurt?

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turkmens. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 468.