Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester (/ˈwʊstər/ (![]() listen) WUUS-tər)[5] is a city in, and county seat of, Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, Worcestershire, England, as of the 2010 Census the city's population was 181,045,[6] making it the second-most populous city in New England after Boston.[lower-alpha 1] Worcester is approximately 40 miles (64 km) west of Boston, 50 miles (80 km) east of Springfield and 40 miles (64 km) north of Providence. Due to its location in Central Massachusetts, Worcester is known as the "Heart of the Commonwealth," thus, a heart is the official symbol of the city. However, the heart symbol may also have its provenance in lore that the Valentine's Day card, although not invented in the city, was first mass-produced and popularized by Worcester resident Esther Howland.[8]

listen) WUUS-tər)[5] is a city in, and county seat of, Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, Worcestershire, England, as of the 2010 Census the city's population was 181,045,[6] making it the second-most populous city in New England after Boston.[lower-alpha 1] Worcester is approximately 40 miles (64 km) west of Boston, 50 miles (80 km) east of Springfield and 40 miles (64 km) north of Providence. Due to its location in Central Massachusetts, Worcester is known as the "Heart of the Commonwealth," thus, a heart is the official symbol of the city. However, the heart symbol may also have its provenance in lore that the Valentine's Day card, although not invented in the city, was first mass-produced and popularized by Worcester resident Esther Howland.[8]

Worcester, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

| City of Worcester | |

Clockwise from top: The Worcester Skyline, the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester Union Station, Bancroft Tower, Paul Revere Road, a triple-decker house on Catharine Street, and City Hall | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The City of the Seven Hills, The Heart of the Commonwealth, Wormtown, Woo-town, The Woo | |

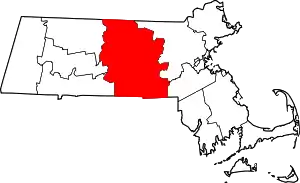

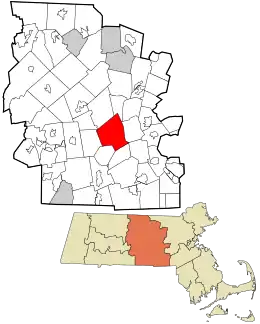

Location within Worcester County | |

Worcester Location within Massachusetts  Worcester Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 42°16′17″N 71°47′56″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Worcester |

| Region | New England |

| Historic countries | Kingdom of England Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Historic colonies | Massachusetts Bay Colony Dominion of New England Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Settled | 1673 |

| Incorporated as a town | June 14, 1722 |

| Incorporated as a city | February 29, 1848 |

| Named for | Worcester, Worcestershire |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • City Manager | Edward M. Augustus Jr. (D) |

| • Mayor | Joseph Petty (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 38.45 sq mi (99.57 km2) |

| • Land | 37.36 sq mi (96.77 km2) |

| • Water | 1.08 sq mi (2.81 km2) |

| Elevation | 480 ft (146 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • City | 181,045 |

| • Estimate (2019)[1] | 185,428[2] |

| • Density | 4,963.01/sq mi (1,916.25/km2) |

| • Metro | 923,672 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP code | 01601–01610, 01612–01615, 01653–01655 |

| Area code(s) | 508 / 774 |

| FIPS code 0 | 25-82000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0617867 |

| GDP | $45.393131 billion (as of 2018, in 2012 US chained dollars)[3] |

| GDP per capita | $45,528 per person[3][4] |

| Website | www |

Worcester was considered its own distinct region apart from Boston until the 1970s. Since then, Boston's suburbs have been extending further westward, especially after the construction of Interstate 495 and Interstate 290. The Worcester region now marks the western periphery of the Boston-Worcester-Providence (MA-RI-NH) U.S. Census Combined Statistical Area (CSA), or Greater Boston. The city features many examples of Victorian-era mill architecture.

History

The area was first inhabited by members of the Nipmuc tribe. The native people called the region Quinsigamond and built a settlement on Pakachoag Hill in Auburn.[9] In 1673 English settlers John Eliot and Daniel Gookin led an expedition to Quinsigamond to establish a new Christian Indian "praying town" and identify a new location for an English settlement. On July 13, 1674, Gookin obtained a deed to eight square miles of land in Quinsigamond from the Nipmuc people and English traders and settlers began to inhabit the region.[10]

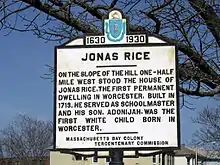

In 1675, King Philip's War broke out throughout New England with the Nipmuc Indians coming to the aid of Indian leader King Philip. The English settlers completely abandoned the Quinsigamond area and the empty buildings were burned by the Indian forces. The town was again abandoned during Queen Anne's War in 1702.[10] Finally in 1713, Worcester was permanently resettled for a third and final time by Jonas Rice.[11] Named after the city of Worcester, England, the town was incorporated on June 14, 1722.[12] On April 2, 1731, Worcester was chosen as the county seat of the newly founded Worcester County government. Between 1755 and 1758, future U.S. president John Adams worked as a schoolteacher and studied law in Worcester.

In the 1770s, Worcester became a center of American revolutionary activity. British General Thomas Gage was given information of patriot ammunition stockpiled in Worcester in 1775. Also in 1775, Massachusetts Spy publisher Isaiah Thomas moved his radical newspaper out of British occupied Boston to Worcester. Thomas would continuously publish his paper throughout the American Revolutionary War. On July 14, 1776, Thomas performed the first public reading in Massachusetts of the Declaration of Independence from the porch of the Old South Church,[14] where the 19th century Worcester City Hall stands today. He would later go on to form the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester in 1812.[15]

During the turn of the 19th century Worcester's economy moved into manufacturing. Factories producing textiles, shoes and clothing opened along the nearby Blackstone River. However, the manufacturing industry in Worcester would not begin to thrive until the opening of the Blackstone Canal in 1828 and the opening of the Worcester and Boston Railroad in 1835. The city transformed into a transportation hub and the manufacturing industry flourished.[16] Worcester was officially chartered as a city on February 29, 1848.[12] The city's industries soon attracted immigrants of primarily Irish, Scottish, French, German, and Swedish descent in the mid-19th century and later many immigrants of Lithuanian, Polish, Italian, Greek, Turkish and Armenian descent.[17] Immigrants moved into new three-decker houses which lined hundreds of Worcester's expanding streets and neighborhoods.[18]

In 1831, Ichabod Washburn opened the Washburn & Moen Company. The company would become the largest wire manufacturing in the country and Washburn became one of the leading industrial and philanthropic figures in the city.[17][19]

Worcester would become a center of machinery, wire products and power looms and boasted large manufacturers, Washburn & Moen, Wyman-Gordon Company, American Steel & Wire, Morgan Construction and the Norton Company. In 1908 the Royal Worcester Corset Company was the largest employer of women in the United States.[20]

Worcester would also claim many inventions and firsts. New England Candlepin bowling was invented in Worcester by Justin White in 1879. Esther Howland began the first line of Valentine's Day cards from her Worcester home in 1847. Loring Coes invented the first monkey wrench and Russell Hawes created the first envelope folding machine.[21] On June 12, 1880, Lee Richmond pitched the first perfect game in Major league baseball history for the Worcester Ruby Legs at the Worcester Agricultural Fairgrounds.[21]

On June 9, 1953, an F4 tornado touched down in Petersham, Massachusetts, northwest of Worcester. The tornado tore through 48 miles of Worcester County including a large area of the city of Worcester. The tornado left massive destruction and killed 94 people. The Worcester Tornado would be the most deadly tornado ever to hit Massachusetts.[22] Debris from the tornado landed as far away as Dedham, Massachusetts.[23]

After World War II, Worcester began to fall into decline as the city lost its manufacturing base to cheaper alternatives across the country and overseas. Worcester felt the national trends of movement away from historic urban centers. The city's population dropped over 20% from 1950 to 1980. In the mid-20th century large urban renewal projects were undertaken to try to reverse the city's decline. A huge area of downtown Worcester was demolished for new office towers and the 1,000,000 sq. ft. Worcester Center Galleria shopping mall.[24] After only 30 years the Galleria would lose most of its major tenants and its appeal to more suburban shopping malls around Worcester County. In the 1960s, Interstate 290 was built right through the center of Worcester, permanently dividing the city. In 1963, Worcester native Harvey Ball introduced the iconic yellow smiley face to American culture.[25][26]

In the late 20th century, Worcester's economy began to recover as the city expanded into biotechnology and healthcare fields.[27] The UMass Medical School has become a leader in biomedical research and the Massachusetts Biotechnology Research Park has become a center of medical research and development.[27] Worcester hospitals Saint Vincent Hospital and UMass Memorial Health Care have become two of the largest employers in the city. Worcester's many colleges, including the College of the Holy Cross, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Clark University, UMass Medical School, Assumption College, MCPHS University, Becker College, and Worcester State University, attract many students to the area and help drive the new economy.

On December 3, 1999, a homeless man and his girlfriend accidentally started a five-alarm fire at the Worcester Cold Storage & Warehouse Company. The fire took the lives of six firemen and drew national attention as one of the worst firefighting tragedies of the late 20th century.[28] President Bill Clinton, Vice President Al Gore and other local and national dignitaries attended the funeral service and memorial program in Worcester.[28]

In recent decades, a renewed interest in the city's downtown has brought new investment and construction to Worcester. A Convention Center was built along the DCU Center arena in downtown Worcester in 1997.[29] In 2000, Worcester's Union Station reopened after 25 years of neglect and a $32 million renovation. Hanover Insurance helped fund a multimillion-dollar renovation to the old Franklin Square Theater into the Hanover Theatre for the Performing Arts.[30] In 2000, the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences built a new campus in downtown Worcester.[31] In 2007 WPI opened the first facility in their new Gateway Park center in Lincoln Square.[32] In 2004, Berkeley Investments proposed demolishing the old Worcester Center Galleria for a new mixed-used development called City Square. The ambitious project looked to reconnect old street patterns while creating a new retail, commercial and living destination in the city.[33] After struggling to secure finances for a number of years, Hanover Insurance took over the project and demolition began on September 13, 2010. Unum Insurance and the Saint Vincent Hospital leased into the project and both facilities opened in 2013. The new Front Street opened on December 31, 2012.[34] In July 2017, Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Karyn Polito and other Baker administration transportation officials visited a construction project in the city to highlight $2.8 billion spent during Baker's administration on highway construction projects and improvements to bridges, intersections, and sidewalks.[35][36]

Building off its history of immigration, Worcester has also become a home for many refugees in recent years. The city has successfully resettled over 2000 refugees coming from over 24 countries. Today, most of these refugees come from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Somalia, Bhutan, Syria, Ukraine and Afghanistan.[37]

Geography

Worcester has a total area of 38.6 square miles (100 km2), 37.6 square miles (97 km2) of land and 1.0 square mile (2.6 km2) (roughly 2.59%) of water. Worcester is bordered by the towns of Auburn, Grafton, Holden, Leicester, Millbury, Paxton, Shrewsbury, and West Boylston.

Worcester is known as the Heart of the Commonwealth, because of its proximity to the center of Massachusetts. The city is about 40 miles (64 km) west of Boston, 50 miles (80 km) east of Springfield, and 38 miles (61 km) northwest of Providence, Rhode Island.

The Blackstone River forms in the center of Worcester by the confluence of the Middle River and Mill Brook. The river courses underground through the center of the city, and emerges at the foot of College Hill. It then flows south through Quinsigamond Village and into Millbury. Worcester is the beginning of the Blackstone Valley that frames the river. The Blackstone Canal was once an important waterway connecting Worcester to Providence and the Eastern Seaboard, but the canal fell into disuse at the end of the 19th century and was mostly covered up. In recent years, local organizations, including the Canal District Business Association, have proposed restoring the canal and creating a Blackstone Valley National Park.[38] In November 2018, the administration of Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker announced a $400,000 grant to streetscape improvements in the Canal District.[39]

Worcester is one of many cities claimed, like Rome, to be found on seven hills: Airport Hill, Bancroft Hill, Belmont Hill (Bell Hill), Grafton Hill, Green Hill, Pakachoag Hill and Vernon Hill. However, Worcester has more than seven hills including Indian Hill, Newton Hill, Poet's Hill, and Wigwam Hill.

Worcester has many ponds and two prominent lakes: Indian Lake and Lake Quinsigamond. Lake Quinsigamond (also known as Long Pond) stretches four miles across the Worcester and Shrewsbury border and is a very popular competitive rowing and boating destination.

Climate

Worcester's humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb) is typical of New England. The weather changes rapidly owing to the confluence of warm, humid air from the southwest; cool, dry air from the north; and the moderating influence of the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Summers are typically hot and humid, while winters are cold, windy, and snowy. Snow typically falls from the second half of November into early April,[40] with occasional falls in October; May snow is much rarer. The USDA classifies the city as straddling hardiness zones 5b and 6a.[41]

The hottest month is July, with a 24-hour average of 70.2 °F (21.2 °C), while the coldest is January, at 24.1 °F (−4.4 °C). There is an average of only 3.5 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs and 4.1 nights of lows at or below 0 °F (−18 °C) per year, and periods of both extremes are rarely sustained. The all-time record high temperature is 102 °F (39 °C), recorded on July 4, 1911,[42] the only 100 °F (38 °C) or greater temperature to date. The all-time record low temperature is −24 °F (−31 °C), recorded on February 16, 1943.[43]

The city averages 48.1 inches (1,220 mm) of precipitation a year, as well as an average of 40–50 inches (100–130 cm) of snowfall a season, receiving far more snow than coastal locations less than 40 miles (64 km) away. Massachusetts' geographic location, jutting out into the North Atlantic, makes the city very prone to Nor'easter weather systems that can dump heavy snow on the region.

While rare, the city has had its share of extreme weather. On September 21, 1938, the city was hit by the brutal New England Hurricane of 1938. Fifteen years later, Worcester was hit by a tornado that killed 94 people. The deadliest tornado in New England history, it damaged a large part of the city and surrounding towns. It struck Assumption Preparatory School, now the site of Quinsigamond Community College.

| Climate data for Worcester Regional Airport (elevation 1000 feet), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1892–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

71 (22) |

84 (29) |

91 (33) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

102 (39) |

99 (37) |

99 (37) |

91 (33) |

79 (26) |

72 (22) |

102 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 52.9 (11.6) |

53.8 (12.1) |

66.3 (19.1) |

78.2 (25.7) |

84.1 (28.9) |

87.5 (30.8) |

89.5 (31.9) |

88.1 (31.2) |

83.7 (28.7) |

74.7 (23.7) |

66.7 (19.3) |

56.7 (13.7) |

91.2 (32.9) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 31.3 (−0.4) |

34.6 (1.4) |

42.9 (6.1) |

55.1 (12.8) |

65.9 (18.8) |

74.1 (23.4) |

78.9 (26.1) |

77.3 (25.2) |

69.6 (20.9) |

58.3 (14.6) |

47.6 (8.7) |

36.3 (2.4) |

56.0 (13.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 16.8 (−8.4) |

19.4 (−7.0) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

37.0 (2.8) |

46.8 (8.2) |

56.0 (13.3) |

61.5 (16.4) |

60.4 (15.8) |

52.9 (11.6) |

41.7 (5.4) |

33.0 (0.6) |

22.6 (−5.2) |

39.6 (4.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −2.3 (−19.1) |

1.5 (−16.9) |

8.1 (−13.3) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

35.6 (2.0) |

44.1 (6.7) |

52.3 (11.3) |

49.7 (9.8) |

39.2 (4.0) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

4.3 (−15.4) |

−4.6 (−20.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −19 (−28) |

−24 (−31) |

−6 (−21) |

9 (−13) |

27 (−3) |

33 (1) |

41 (5) |

38 (3) |

27 (−3) |

19 (−7) |

3 (−16) |

−17 (−27) |

−24 (−31) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.49 (89) |

3.23 (82) |

4.21 (107) |

4.11 (104) |

4.19 (106) |

4.19 (106) |

4.23 (107) |

3.71 (94) |

3.93 (100) |

4.68 (119) |

4.28 (109) |

3.82 (97) |

48.07 (1,220) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 17.1 (43) |

15.6 (40) |

11.4 (29) |

2.8 (7.1) |

trace | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

2.6 (6.6) |

14.4 (37) |

64.1 (163) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12.5 | 10.5 | 12.9 | 12.4 | 13.6 | 12.3 | 10.9 | 10.1 | 9.9 | 10.5 | 11.6 | 12.2 | 139.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8.5 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 7.0 | 31.7 |

| Source: NOAA[40][44][45] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods

Gallery

Worcester and the surrounding areas in 2006, looking north from 3700 feet (1128 m). Route 146 can be seen under construction.

Worcester and the surrounding areas in 2006, looking north from 3700 feet (1128 m). Route 146 can be seen under construction. Dodge Park

Dodge Park Washburn Shops, 1868

Washburn Shops, 1868 Cristoforo Colombo Park

Cristoforo Colombo Park Cristoforo Colombo Park

Cristoforo Colombo Park

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 2,095 | — | |

| 1800 | 2,411 | 15.1% | |

| 1810 | 2,577 | 6.9% | |

| 1820 | 2,962 | 14.9% | |

| 1830 | 4,173 | 40.9% | |

| 1840 | 7,497 | 79.7% | |

| 1850 | 17,049 | 127.4% | |

| 1860 | 24,960 | 46.4% | |

| 1870 | 41,105 | 64.7% | |

| 1880 | 58,291 | 41.8% | |

| 1890 | 84,655 | 45.2% | |

| 1900 | 118,421 | 39.9% | |

| 1910 | 145,986 | 23.3% | |

| 1920 | 179,754 | 23.1% | |

| 1930 | 195,311 | 8.7% | |

| 1940 | 193,694 | −0.8% | |

| 1950 | 203,486 | 5.1% | |

| 1960 | 186,587 | −8.3% | |

| 1970 | 176,572 | −5.4% | |

| 1980 | 161,799 | −8.4% | |

| 1990 | 169,759 | 4.9% | |

| 2000 | 172,648 | 1.7% | |

| 2010 | 181,045 | 4.9% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 185,428 | [1] | 2.4% |

| source:[46] | |||

According to the 2010 U.S. Census, Worcester had a population of 181,045, of which 88,150 (48.7%) were male and 92,895 (51.3%) were female. In terms of age, 77.9% were over 18 years old and 11.7% were over 65 years old; the median age is 33.4 years. The median age for males is 32.1 years and 34.7 years for females.

In terms of race and ethnicity, Worcester's population was 69.4% White, 11.6% Black or African American, 0.4% American Indian and Alaska Native, 6.1% Asian (3.0% Vietnamese, 0.9% Chinese, and 0.8% Asian Indian), <0.1% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, 8.4% from Some Other Race, and 4.0% from Two or More Races (1.2% White and Black or African American; 1.0% White and Some Other Race). Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 20.9% of the population (12.7% Puerto Rican).[47] Non-Hispanic Whites were 59.6% of the population in 2010,[48] down from 96.8% in 1970.[49]

Income

Data is from the 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.[50][51][52]

| Rank | ZIP Code (ZCTA) | Per capita income |

Median household income |

Median family income |

Population | Number of households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Massachusetts | $35,763 | $66,866 | $84,900 | 6,605,058 | 2,530,147 | |

| 1 | 01606 | $32,781 | $66,912 | $86,452 | 19,495 | 8,032 |

| Worcester County | $31,537 | $65,223 | $81,519 | 802,688 | 299,663 | |

| 2 | 01602 | $31,101 | $62,832 | $77,807 | 23,707 | 9,025 |

| United States | $28,155 | $53,046 | $64,719 | 311,536,594 | 115,610,216 | |

| 3 | 01604 | $27,119 | $49,797 | $54,984 | 34,720 | 14,388 |

| Worcester | $24,330 | $45,932 | $57,704 | 181,901 | 68,850 | |

| 4 | 01607 | $24,044 | $45,152 | $56,815 | 8,957 | 3,602 |

| 5 | 01609 | $23,846 | $40,660 | $60,867 | 21,178 | 7,183 |

| 6 | 01603 | $22,315 | $48,183 | $55,000 | 19,385 | 7,243 |

| 7 | 01605 | $21,639 | $37,705 | $40,710 | 27,279 | 10,640 |

| 8 | 01610 | $14,040 | $30,532 | $35,372 | 23,964 | 7,453 |

| 9 | 01608 | $11,315 | $19,418 | $19,727 | 3,558 | 1,455 |

Government

| County-level state agency heads | |

|---|---|

| Clerk of Courts: | Dennis P. McManus (D) |

| District Attorney: | Joe Early Jr. (D) |

| Register of Deeds: | Katie Toomey (D) |

| Register of Probate: | Stephanie Fattman (R) |

| County Sheriff: | Lew Evangelidis (R) |

| State government | |

| State Representative(s): | Jim O'Day (D) David LeBoeuf (D) Dan Donahue (D) John Mahoney (D) Mary Keefe (D) |

| State Senator(s): | Michael Moore (D) Harriette Chandler (D-1st Worcester district) |

| Governor's Councilor(s): | Jen Caissie (R) |

| Federal government | |

| U.S. Representative(s): | Jim McGovern (D-MA-02) |

| U.S. Senators: | Elizabeth Warren (D), Ed Markey (D) |

Worcester is governed by a Council-manager government with a popularly elected mayor. A city council acts as the legislative body, and the council-appointed manager handles the traditional day-to-day chief executive functions.

City councilors can run as either a representative of a city district or as an at-large candidate. The winning at-large candidate who receives the greatest number of votes for mayor becomes the mayor (at-large councilor candidates must ask to be removed from the ballot for mayor if they do not want to be listed on the mayoral ballot). As a result, voters must vote for their mayoral candidate twice, once as an at-large councilor, and once as the mayor. The mayor has no more authority than other city councilors, but is the ceremonial head of the city and chair of the city council and school committee. Currently, there are 11 councilors: 6 at-large and 5 district.

Worcester's first charter, which went into effect in 1848, established a Mayor/Bicameral form of government. Together, the two chambers — the 11-member Board of Aldermen and the 30-member Common Council — were vested with complete legislative powers. The mayor handled all administrative departments, though appointments to those departments had to be approved by the two-chamber City Council.

Seeking to replace the 1848 charter, Worcester voters in November 1947 approved a change to Plan E municipal government. In effect from January 1949 until November 1985, this charter (as outlined in chapter 43 of the Massachusetts General Laws) established City Council/City Manager government. This type of governance, with modifications, has survived to the present day.

Initially, Plan E government in Worcester was organized as a 9-member council (all at-large), a ceremonial mayor elected from the council by the councilors, and a council-appointed city manager. The manager oversees the daily administration of the city, makes all appointments to city offices, and can be removed at any time by a majority vote of the council. The mayor chairs the city council and the school committee, and does not have the power to veto any vote.[53]

From 1949 through 1959, elections were by the single transferable vote. Voters repealed that system in November 1960. Despite non-partisan elections, two groups alternated in control of council: the local Democratic Party and a slate known as the Citizens' Plan E Association (CEA). CEA members included the Republican Party leadership and other groups not affiliated with the regular Democratic Party.[54]

In 1983, Worcester voters again decided to change the city charter. This "Home Rule" charter (named for the method of adoption of the charter) is similar to Plan E, the major changes being to the structure of the council and the election of the mayor. The 9-member Council became 11, 6 at-large and 1 from each city district. The mayor is chosen by popular election, but must also run and win as an at-large councilor.

Politics

Worcester's history of social progressivism includes a number of temperance and abolitionist movements. It was a leader in the women's suffrage movement: The first national convention advocating women's rights was held in Worcester, October 23–24, 1850.[55]

Two of the nation's most radical abolitionists, Abby Kelley Foster and her husband Stephen S. Foster, adopted Worcester as their home, as did Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the editor of The Atlantic Monthly and Emily Dickinson's avuncular correspondent, and Unitarian minister Rev. Edward Everett Hale.

The area was already home to Lucy Stone, Eli Thayer, and Samuel May, Jr. They were joined in their political activities by networks of related Quaker families such as the Earles and the Chases, whose organizing efforts were crucial to the anti-slavery cause in central Massachusetts and throughout New England.

Anarchist Emma Goldman and two others opened an ice cream shop in 1892. "It was spring and not yet warm," Goldman later wrote, "but the coffee I brewed, our sandwiches, and dainty dishes were beginning to be appreciated. Within a short time, we were able to invest in a soda-water fountain and some lovely colored dishes."[56]

On October 19, 1924, the largest gathering of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) ever held in New England took place at the Agricultural Fairgrounds in Worcester. Klansmen in sheets and hoods, new Knights awaiting a mass induction ceremony, and supporters swelled the crowd to 15,000. The KKK had hired more than 400 "husky guards", but when the rally ended around midnight, a riot broke out. Klansmen's cars were stoned and burned, and their windows smashed. KKK members were pulled from their cars and beaten. Klansmen called for police protection, but the situation raged out of control for most of the night. The violence after the "Klanvocation" had the desired effect: Membership fell off, and no further public Klan meetings were held in Worcester.[57]

Robert Stoddard, owner of The Telegram and Gazette, was one of the founders of the John Birch Society.

Sixties era radical Abbie Hoffman was born in Worcester in 1936 and spent more than half of his life in the city.

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of October 19, 2016 – Worcester[58] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 44,656 | 44.75% | |||

| Republican | 8,583 | 8.22% | |||

| Unenrolled | 49,487 | 47.37% | |||

| Political Designations | 0 | 0% | |||

| Total | 107,686 | 100% | |||

Public safety

For public safety needs, the City of Worcester is protected by both the Worcester Fire Department and the Worcester Police Department.

UMass Memorial Medical Center provides emergency medical services (EMS) under contract with the city. Originally operated by Worcester City Hospital and later by the University of Massachusetts Medical School,[59] "Worcester EMS" operates exclusively at the advanced life support (ALS) level, with two paramedics staffing each ambulance.[60] UMass Memorial EMS maintains two community EMS stations and operates a fleet of 18 ambulances (including spares), as well as a special-operations trailer, several other support vehicles, and a bike team; the agency responds to an average of 100 emergencies each day.[61] UMass Memorial EMS operates the EMS Communications Center, which is a secondary PSAP and provides emergency medical dispatch (EMD) services to Worcester and other communities.[62]

Economy

By the mid-19th century Worcester was one of New England's largest manufacturing centers. The city's large industries specialized in machinery, wire production, and power looms. Although manufacturing has declined, the city still maintains large manufactures, like Norton Abrasives, which was bought by Saint-Gobain in 1990, Morgan Construction Company, since bought by Siemens and then bought by Japanese company PriMetals Technologies, and the David Clark Company. The David Clark Company pioneered aeronautical equipment including anti-gravity suits and noise attenuating headsets.

Services, particularly education and healthcare, make up a large portion of the city's economy. Worcester's many colleges and universities make higher education a considerable presence in the city's economy. Hanover Insurance was founded in 1852 and retains its headquarters in Worcester. Unum Insurance and Fallon Community Health Plan have offices in the city. Polar Beverages is the largest independent soft-drink bottler in the country and is in Worcester.

Worcester is home to the largest concentration of digital gaming students in the United States.[63] The Memorial Auditorium, built as a tribute to World War I veterans of Worcester, is undergoing a renovation and may cater to these Digital Students as a future multimedia and digital center, in conjunction with the twelve Worcester colleges and universities.

As one of the top ten emerging hubs for tech startups,[64] the city's biotechnology and technology industries have helped spur major expansions at both the University of Massachusetts Medical School and Worcester Polytechnic Institute. The Massachusetts Biotechnology Research Park hosts many innovative companies including Advanced Cell Technology and AbbVie. The Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology in nearby Shrewsbury developed the oral contraceptive pill in 1951.

Downtown Worcester used to boast major Boston retailers Filene's and Jordan Marsh as well Worcester's own department stores Barnard's and Denholm & McKay. Over time most retailers moved away from downtown and into the suburban Auburn Mall and Greendale Mall in North Worcester.

In 2010,[65] the median household income was $61,212. Median family income was $76,485. The per capita income was $29,316. About 7.7% of families and 10.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.1% of those under age 18 and 7.5% of those age 65 or over. In October 2013, Worcester was found to be the number five city for investing in a rental property.[66]

In November 2016, the administration of Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker announced a $2.3 million grant to the city to redevelop its downtown area for greater walkability.[67] In January 2017, Baker signed into law a bill allowing 44 acres of unused state-owned land on the former Worcester State Hospital campus to be converted into a biomanufacturing industrial park.[68] In November 2017, Baker's administration and the Worcester Business Development Corporation signed a land disposition agreement for the park.[69]

Top employers

According to the city's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[70] the top ten employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | UMass Memorial Health Care | 13,745 |

| 2 | City of Worcester | 5,473 |

| 3 | University of Massachusetts Medical School | 4,172 |

| 4 | Reliant Medical Group | 2,680 |

| 5 | Saint Vincent Hospital | 2,450 |

| 6 | Hanover Insurance | 1,800 |

| 7 | Saint-Gobain | 1,652 |

| 8 | Seven Hills Foundation | 1,445 |

| 9 | Worcester Polytechnic Institute | 1,283 |

| 10 | Community Healthlink | 1,200 |

Education

Primary and secondary education

Worcester's public schools educate more than 25,000 students in pre-kindergarten through 12th grade.[71] The system consists of 34 elementary schools, 4 middle schools, 7 high schools,[72] and several other learning centers such as magnet schools, alternative schools, and special education schools. The city's public school system also administers an adult education component called "Night Life", and operates a Public-access television cable TV station on channel 11. In June 2015, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker announced a $1.3 million grant to the Elm Park Community School.[73]

Worcester Technical High School opened in 2006, replacing the old Worcester Vocational High School, or "Voke". The city's other public high schools include South High Community School, North High School, Doherty Memorial High School, Burncoat Senior High School, University Park Campus School, and Claremont Academy.

In 2014, Worcester Tech's graduating class was honored by having President Barack Obama as the speaker at their graduation ceremony.

The Massachusetts Academy of Math and Science was founded in 1992 as a public secondary school at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

One notable charter school in the city is Abby Kelley Foster Charter Public School, which teaches kindergarten through 12th grade. It is granted status by Massachusetts as a Level 1 school. It is the one of 834 schools in the United States to offer the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme.

Twenty-one private and parochial schools are also found throughout Worcester, including the city's oldest educational institution, Worcester Academy, founded in 1834, and Bancroft School, founded in 1900.

Higher education

Worcester is home to nine institutes of higher education.

- Assumption College is the fourth oldest Roman Catholic college in New England and was founded in 1904. At 175 acres (0.71 km2), it has the largest campus in Worcester.

- Becker College is a private college with campuses in Worcester and Leicester, Massachusetts. It was founded in Leicester in 1784 as Leicester Academy. The Worcester campus was founded in 1887, and the two campuses merged into Becker College in 1977. Becker's video game design program has consistently been ranked in the top 10 in the U.S. and Canada.[74]

- Clark University was founded in 1887 as the first all-graduate school in the country; it now also educates undergraduates and is noted for its strengths in psychology and geography. Its first president was G. Stanley Hall, the founder of organized psychology as a science and profession, father of the child study movement, and founder of the American Psychological Association. Well-known professors include Albert A. Michelson, who won the first American Nobel Prize in 1902 for his measurement of light. Robert H. Goddard, a pioneering rocket scientist of the space age also studied and taught here, and, in his only visit to the United States, Sigmund Freud delivered his five famous "Clark Lectures" at the university. Clark offers the only program in the country leading to a Ph.D. in Holocaust History and Genocide Studies.

- College of the Holy Cross was founded in 1843 and is the oldest Roman Catholic college in New England and one of the oldest in the United States. Well-known graduates include Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Nobel laureate Joseph E. Murray; former Poet Laureate of the United States Billy Collins; Basketball Hall of Fame member Bob Cousy; attorney and professional sports' team owner Edward Bennett Williams; College Football Hall of Fame member Gordie Lockbaum; and Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. In 2013, Holy Cross was ranked by U.S. News and World Report as the nation's 25th highest-rated liberal arts college.[75]

- The Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences Worcester Campus houses the institution's Doctor of Optometry program, accelerated Doctor of Pharmacy, Post-Baccalaureate Bachelor's in Nursing; Master's in Nursing – Family Nurse Practitioner, Master's program New England School of Acupuncture, as well as the Master's program in Physician Assistant Studies for post-baccalaureate students.

- Quinsigamond Community College was founded in 1963 and provides associate degree and professional certificate options to its 13,000 students per year. In addition to its main campus, students train and study at multiple program sites throughout Worcester as well as one in Marlborough and one in Southbridge.[76]

- The University of Massachusetts Medical School (1970) is one of the nation's top 50 medical schools. Dr. Craig Mello won the 2006 Nobel Prize for Medicine. The University of Massachusetts Medical School is ranked fourth in primary care education among America's 125 medical schools in the 2006 U.S. News & World Report annual guide "America's Best Graduate Schools".[77]

- Worcester Polytechnic Institute (1865) is an innovative leader in engineering education and partnering with local biotechnology industries. Robert Goddard, the father of modern rocketry, graduated from WPI in 1908 with a Bachelor of Science in physics.

- Worcester State University is a public, 4-year college founded in 1874 as Worcester Normal School.

An early higher education institution, the Oread Institute, closed in 1934.

Many of these institutions participate in the Colleges of Worcester Consortium. This independent, non-profit collegiate association includes academic institutions in Worcester and other communities in Worcester County, such as Anna Maria College in neighboring Paxton. It facilitates cooperation among the colleges and universities. One example of this being its inter-college shuttle bus and student cross registration.

Culture

Much of the world renowned Worcester culture is synonymous with New England culture. The city's name is notoriously mispronounced by people unfamiliar with the city. As with the city in England, the first syllable of "cester" (castra) is left entirely unvoiced. Combined with a traditionally non-rhotic Eastern New England English accent, the name can be transcribed as "WOOS-tuh" or "WISS-tuh" (the first syllable possibly having a near-close central unrounded vowel).[80]

Worcester has many traditionally ethnic neighborhoods, including Quinsigamond Village (Swedish), Shrewsbury Street (Italian), Kelley Square (Irish and Polish), Vernon Hill (Lithuanian), Union Hill (Jewish), and Main South (Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Vietnamese).

Shrewsbury Street is Worcester's traditional "Little Italy" neighborhood and today boasts many of the city's most popular restaurants and nightlife.[81] The Canal District was once an old eastern European neighborhood, but has been redeveloped into a very popular bar, restaurant and club scene.[82]

Worcester is also famously the former home of the Worcester Lunch Car Company. The company began in 1906 and built many famous lunch car diners in New England. Worcester is home to many classic lunch car diners including Boulevard Diner, Corner Lunch, Chadwick Square Diner, and Miss Worcester Diner.

There are also many dedicated community organizations and art associations in the city. stART on the Street is an annual festival promoting local art. The Worcester Music Festival and New England Metal and Hardcore Festival are also held annually in Worcester. The Worcester County St. Patrick's Parade runs through Worcester and is one of the largest St. Patrick's Day celebrations in the state. The city also hosts the second oldest First Night celebration in the country each New Year's Eve.

Worcester is also the state's largest center for the arts outside of Boston. Mechanics Hall, built in 1857, is one of the oldest concert halls in the country and is renowned for its pure acoustics.[83] In 2008 the old Poli Palace Theatre reopened as the Hanover Theatre for the Performing Arts.[84] The theatre brings many Broadway shows and nationally recognized performers to the city. Tuckerman Hall, designed by one of the country's earliest woman architects, Josephine Wright Chapman, is home to the Massachusetts Symphony Orchestra. The DCU Center arena and convention holds many large concerts, exhibitions and conventions in the city. The Worcester County Poetry Association sponsors readings by national and local poets in the city and the Worcester Center for Crafts provides craft education and skills to the community. Worcester is also home to the Worcester Youth Orchestras.[85] Founded in 1947 by Harry Levenson, it is the 3rd oldest youth orchestra in the country and regularly performs at Mechanics Hall.

The nickname Wormtown is synonymous with the city's once large underground rock music scene. The nickname has now become used to refer to the city itself.[86][87][88]

Sites of interest

Worcester has 1,200 acres of publicly owned property. Notable parks include Elm Park, which was laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1854, and the City Common laid out in 1669. Both parks are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[89] The largest park in the city is the 549 acre Green Hill Park. The park was donated by the Green family in 1903 and includes the Green Hill Park Shelter built in 1910. In 2002, the Massachusetts Vietnam Veterans Memorial was dedicated in Green Hill Park. Other Parks, include Newton Hill, East Park, Morgan Park, Shore Park, Crompton Park, Hadwen Park, Institute Park and University Park. Though not within city limits, Tower Hill Botanical Garden is operated by the Worcester County Horticultural Society and is a 20-minute drive northeast of the city in Boylston. The Horticultural Society's former headquarters is now the Worcester Historical Museum, dedicated to the cultural, economic, and scientific contributions of the city to American society. As a former manufacturing center, Worcester has many historic 19th century buildings and on the National Register of Historic Places, including the old facilities of the Crompton Loom Works, Ashworth and Jones Factory and Worcester Corset Company Factory.

The American Antiquarian Society has been in Worcester since 1812. The national library and society has one of the largest collections of early American history in the world. The city's main museum is the Worcester Art Museum established in 1898. The museum is the second largest art museum in New England, behind the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.[90] From 1931 to 2013, Worcester was home to the Higgins Armory Museum, which was the sole museum dedicated to arms and armor in the country.[91] Its collection and endowment were transferred and integrated into the Worcester Art Museum, with the collection now being shown in a new gallery which opened in 2015. The non-profit Veterans Inc. is headquartered at the southern tip of Grove Street in the historic Massachusetts National Guard Armory building.

The Worcester Memorial Auditorium is one of the most prominent buildings in the city. Built as a World War I war memorial in 1933, the multipurpose auditorium has hosted many of the Worcester's most famous concerts and sporting events, and is undergoing a renovation to become a multi media Center and digital arts auditorium, and event Center.

Sports

Worcester was home to Marshall Walter ("Major") Taylor, an African American cyclist who won the world one-mile (1.6 km) track cycling championship in 1899. Taylor's legacy includes being the first African American and the second black athlete to be a world champion (Canadian boxer George Dixon, 1892). Taylor was nicknamed the Worcester Whirlwind by the local papers.

Lake Quinsigamond is home to the Eastern Sprints, a premier rowing event in the United States. Competitive rowing teams first came to Lake Quinsigamond in 1857. Finding the long, narrow lake ideal for such crew meets, avid rowers established boating clubs on the lake's shores, the first being the Quinsigamond Boating Club. More boating clubs and races followed, and soon many colleges (local, national, and international) held regattas, such as the Eastern Sprints, on the lake. Beginning in 1895, local high schools held crew races on the lake. In 1952, the lake played host to the National Olympic rowing trials.

In 2002, the Jesse Burkett Little League all-stars team went all the way to the Little League World Series. They made it to the US final before losing to Owensboro, Kentucky. Jesse Burkett covers the West Side area of Worcester, along with Ted Williams Little League.

The city hosts the Worcester Railers of the ECHL, which began play in October 2017. Prior to the Railers, the American Hockey League team Worcester Sharks played in Worcester from 2006 to 2015, before relocating to San Jose. The Sharks played at the DCU Center as a developmental team for the National Hockey League's San Jose Sharks. The AHL was formerly represented by the Worcester IceCats from 1994 to 2005. The IceCats were chiefly affiliated with the St. Louis Blues. The city hosted the Worcester Blades of the Canadian Women's Hockey League (CWHL) for one season, playing their 2018–19 home games in the Fidelity Bank Worcester Ice Center for that league's final season.

Worcester now hosts the Massachusetts Pirates, an indoor football team in the National Arena League, which started in 2018 at the DCU Center. The city previously was home to the New England Surge of the defunct Continental Indoor Football League.

The city's former professional baseball team, the Worcester Tornadoes, started in 2005 and was a member of the Canadian-American Association of Professional Baseball League. The team played at the Hanover Insurance Park at Fitton Field on the campus of the College of the Holy Cross and was not affiliated with any major league team. The Tornadoes won the 2005 Can-Am League title. The team's owner ran into financial difficulties, and the team disbanded after the 2012 season. The Worcester Bravehearts began play in 2014 as the local affiliate of the Futures Collegiate Baseball League, and won the league championship in their inaugural season. The Pawtucket Red Sox, the AAA affiliate of the Boston Red Sox, will be moving to Polar Park in 2021. The name of the new team will be the Worcester Red Sox.[92][93]

Candlepin bowling was invented in Worcester in 1880 by Justin White, an area bowling alley owner. The Worcester County Wildcats,[94] part of the New England Football League, is a semi-pro football team, and play at Commerce Bank Field at Foley Stadium.

Golf's Ryder Cup's first official tournament was played at the Worcester Country Club in 1927. The course also hosted the U.S. Open in 1925, and the U.S. Women's Open in 1960.

Worcester's colleges have long histories and many notable achievements in collegiate sports. The College of the Holy Cross represents NCAA Division 1 sports in Worcester. The other colleges and Universities in Worcester correspond with division II and III. The Holy Cross Crusaders won the NCAA men's basketball champions in 1947 and NIT men's basketball champions in 1954, led by future NBA hall-of-famers and Boston Celtic legends Bob Cousy and Tom Heinsohn.

Religion

.jpg.webp)

According to the U.S. Religion Census 2010, the largest religious denomination in Worcester County is Catholicism, followed by Protestantism. The first Catholics came to Worcester in 1826. They were chiefly Irish immigrants brought to America by the builders of the Blackstone canal. As time went on and the number of Catholics increased, the community petitioned Bishop Fenwick to send them a priest. In response to this appeal, the bishop appointed the Reverend James Fitton to visit the Catholics of Worcester in 1834. A Catholic Mass was first offered in the city in an old stone building on Front Street. The foundation of Christ's Church, the first Catholic church in Worcester (now St. John's), was laid on July 6, 1834.[95] The Roman Catholic Diocese of Worcester was canonically erected on January 14, 1950, by Pope Pius XII. Its territories were taken from the neighboring Diocese of Springfield. The current and fifth bishop is Robert Joseph McManus.[96]

| Religious adherence Worcester County 2010[97] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Religion | Number of adherents | Percentage |

| Catholic | 348,625 | 38.01% |

| Mainline Protestant | 49,656 | 5.4% |

| Evangelical Protestant | 42,006 | 4.6% |

| Eastern Orthodox | 8,140 | 0.9% |

| Jewish | 4,605 | 0.5% |

| Black Protestant | 677 | 0.01% |

| Other | 15,445 | 1.68% |

| None | 447,826 | 48.84% |

| Total | 100% | |

The Unitarian-Universalist Church of Worcester was founded in 1841. Worcester's Greek Orthodox Cathedral, St. Spyridon, was founded in 1924.

Worcester is home to a dedicated Jewish population who attend five synagogues, including Reform congregation Temple Emanuel Sinai, Congregation Beth Israel, a Conservative synagogue founded in 1924,[98] and Orthodox Congregation Tifereth Israel – Sons of Jacob (Chabad), home of Yeshiva Achei Tmimim Academy. Beth Israel and its rabbi were the subject of the book And They Shall be My People: An American Rabbi and His Congregation by Paul Wilkes.

The first Armenian Church in the Western Hemisphere was built in Worcester in 1890 and consecrated on January 18, 1891, as "Soorp Purgich" (Holy Savior). The current sanctuary of the congregation, now known as Armenian Church of Our Savior, was consecrated in 1952.[99]

Worcester is home to America's largest community of Mandaeans, numbering around 2,500. Most Mandaeans in Worcester arrived as refugees from instability in Iraq during the early 21st century.[100]

Media

The Telegram & Gazette is Worcester's only daily newspaper. The paper, known locally as "the Telegram" or "the T and G", is wholly owned by GateHouse Media of Fairport, New York.[101] WCTR, channel 3, is Worcester's local news television station, and WUNI-TV, channel 27, is the only major over-the-air broadcast television station in Worcester. Radio stations based in Worcester include WCHC, WCUW, WSRS, WTAG, WWFX, WICN and WXLO. WCCA-TV shows on channel 194 and provides Community Cable-Access Television as well as a live stream of the channel on their website WCCATV.com.[102]

Notable people

- Nathaniel Bar-Jonah – serial killer, child molester and suspected cannibal

- Harvey Ball – designer of the iconic smiley face logo

- H. Jon Benjamin – actor

- Mike Birbiglia – comedian

- Bob Cousy – NBA Hall-of-Famer; attended Holy Cross; resident of Worcester since the early 1950s

- John Dufresne – novelist; Guggenheim Fellow

- Rich Gedman – former MLB player; starting catcher on 1986 AL champion Boston Red Sox

- Robert Goddard – creator of the world's first liquid-fueled rocket

- Alice Hollister - actress

- Abbie Hoffman – civil rights leader

- Jean Louisa Kelly – actress

- Jordan Knight – singer

- Luke Caswell, better known as Cazwell, a LGBT rapper

- Jarrett J. Krosoczka – author and illustrator

- Stanley Kunitz – poet

- Denis Leary – actor and comedian

- Joyner Lucas – rapper

- Sam Seder – talk radio host and comedian

- Doug Stanhope – comedian

- Erik Per Sullivan – actor

- Major Taylor – champion cyclist and cycling pioneer

- Alicia Witt – actress

- Geoffrey Zakarian – celebrity chef

- Helen Walker – actress

Infrastructure

Transportation

Worcester is served by several interstate highways. Interstate 290 (I-290) connects central Worcester to I-495, I-90 in nearby Auburn, and I-395. I-190 links Worcester to Route 2 and the cities of Fitchburg and Leominster in northern Worcester County. I-90 can also be reached via a connecting segment of Route 146.

Worcester is also served by several smaller Massachusetts state highways. Route 9 links the city to its eastern and western suburbs, Shrewsbury and Leicester. Route 9 runs almost the entire length of the state, connecting Boston and Worcester with Pittsfield, near the New York state border. Route 12 was the primary route north to Leominster and Fitchburg until the completion of I-190. Route 12 also connected Worcester to Webster before I-395 was completed. It still serves as an alternative local route. Route 146, the Worcester-Providence Turnpike, connects the city with the similar city of Providence, Rhode Island. Route 20 touches the southernmost tip of Worcester near the Massachusetts Turnpike. Route 20 is a coast-to-coast route connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, and is the longest road in the United States.[103]

Worcester is the headquarters of the Providence and Worcester, a Class II railroad operating throughout much of southern New England. Worcester is also the western terminus of the Framingham/Worcester commuter rail line run by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Union Station serves as the hub for commuter railway traffic. Built in 1911, the station has been restored to its original grace and splendor, reopening to full operation in 2000. It also serves as an Amtrak stop, serving the Lake Shore Limited from Boston to Chicago. In October 2008, the MBTA added 5 new trains to the Framingham/Worcester line as part of a plan to add 20 or more trains from Worcester to Boston and also to buy the track from CSX Transportation.[104] Train passengers may also connect to additional services such as the Vermonter line in Springfield.

The Worcester Regional Transit Authority, or WRTA, manages the municipal bus system. Buses operate intracity as well as connect Worcester to surrounding central Massachusetts communities. Worcester is also served by OurBus, Peter Pan Bus Lines and Greyhound Bus Lines, which operate out of Union Station.

Worcester Regional Airport (KORH), owned and operated by Massport since 2010, lies at the top of Tatnuck Hill, Worcester's highest point. The airport has two runways, their lengths are 7,000 ft (2,100 m) and 5,000 ft (1,500 m), and a $15.7 million terminal.[105] The airport was serviced by numerous airlines from the 1950s through the 1990s, but since then has encountered years of spotty commercial service.

Healthcare

In 1830, state legislation funded the creation of the Worcester State Insane Asylum Hospital (1833) and became one of the first new public asylums in the United States.[106] Prior the Worcester State Insane Asylum hospital, all other treatment centers were funded by private philanthropists which neglected treatment for the poor.[106]

Worcester is home to the University of Massachusetts Medical School, ranked fourth in primary care education among America's 125 medical schools in the 2006 U.S. News & World Report annual guide "America's Best Graduate Schools".[77] The medical school is in the top quartile of medical schools nationally in research funding from the NIH and is home to highly respected scientists including a Nobel laureate, a Lasker Award recipient and multiple members of the National Academy of Sciences and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The school is closely affiliated with UMass Memorial Health Care, the clinical partner of the medical school, which has expanded its locations all over Central Massachusetts. St. Vincent Hospital at Worcester Medical Center in the downtown area rounds out Worcester's primary care facilities. Reliant Medical Group, formerly Fallon Clinic, is the largest private multi-specialty group in central Massachusetts with over 30 different specialties. It is affiliated with St. Vincent's Hospital in downtown Worcester. Reliant Medical Group was the creator of Fallon Community Health Plan, a now independent HMO based in Worcester, and one of the largest health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in the state.

Utilities and public services

Worcester has a municipally owned water supply. Sewage disposal services are provided by the Upper Blackstone Water Pollution Abatement District, which services Worcester as well as some surrounding communities. National Grid USA is the exclusive distributor of electric power to the city, though due to deregulation, customers now have a choice of electric generation companies. Natural gas is distributed by NSTAR Gas; only commercial and industrial customers may choose an alternate natural gas supplier. Verizon, successor to New England Telephone, NYNEX, and Bell Atlantic, is the primary wired telephone service provider for the area. Phone service is also available from various national wireless companies. Cable television is available from Charter Communications, with Broadband Internet access also provided, while a variety of DSL providers and resellers are able to provide broadband Internet over Verizon-owned phone lines.

Sister cities

Worcester has the following sister cities:[107]

Worcester, United Kingdom (1998)

Worcester, United Kingdom (1998) Afula, Israel

Afula, Israel Piraeus, Greece (2005)

Piraeus, Greece (2005) Pushkin, Saint Petersburg, Russia (1987)

Pushkin, Saint Petersburg, Russia (1987)

See also

Notes

- The third largest city is Providence, Rhode Island, with a population of 178,042.[7]

References

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Archived from the original on July 26, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Worcester city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- "Total Real Gross Domestic Product for Worcester, MA-CT (MSA)". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. January 2001. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- In 2012 chained US dollars. Calculated on the basis of the 2018 GDP figure, with the 2010 census-recorded population. Formula:

45.393131*10**9/181045. - How do you say 'Worcester?', archived from the original on May 4, 2015, retrieved August 1, 2015CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Worcester city, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Providence city, Rhode Island". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- "Valentines weren't invented in Worcester, but they have special history here". Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- Lincoln, William (1862). History of Worcester, Massachusetts, pp. 22–23. Worcester: Charles Hersey.

- "Hassanamisco Indian Museum History". Hassanamisco Indian Museum. 2013. Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Worcester Society of Antiquity (1903). Exercises Held at the Dedication of a Memorial to Major Jonas Rice, the First Permanent Settler of Worcester, Massachusetts, Wednesday, October 7, 1903. Charles Hamilton Press, Worcester. 72pp.

- "Worcester, MA History | at the dawn of the American Industrial Revolution". City of Worcester, Massachusetts. 2007. Archived from the original on March 4, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Coombs, Zelotes W. "Worcester & Worcester Common". City of Worcester, Massachusetts. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- Hutchins, Fred L. (1899). "Fixing the Spot". Proceedings of the Worcester Society of Antiquity. 16: 88.

- "American Antiquarian Society Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- "Transportation". Worcester Historical Museum. 2013. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Dan Ricciardi; Kathryn Mahoney (2013). "Washburn and Moen Worcester's Worldwide Wire Manufacturuer". College of the Holy Cross. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- "Three Deckers". Worcester Historical Museum. 2013. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- "Worcester, MA Driving Tour & Guide to Blackstone Canal Historic Markers". Archived from the original on February 4, 2007. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- Gaultney, Bruce (2009). Worcester Memories, pp. 21. Early 1990s.

- Gaultney, Bruce (2009). Worcester Memories, pp. 7. 1880s.

- Gaultney, Bruce (2009). Worcester Memories, pp. 79. 1950s.

- Parr, James L. (2009). Dedham: Historic and Heroic Tales From Shiretown. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-750-0.

- "City Square Slideshow". Worcester Telegram & Gazette. December 30, 2013. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Honan, William H. (April 14, 2001). "H. R. Ball, 79, Ad Executive Credited With happy Face". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- Adams, Cecil (April 23, 1993). "Who invented the smiley face?". The Straight Dope. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- "Enterprise Timeline". Worcester Historical Museum. 2013. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Gaultney, Bruce (2009). Worcester Memories, pp. 113. 1970s, '80s & '90s.

- "Facility Info". DCU Center. September 25, 2005. Archived from the original on November 25, 2005.

- "Restoration". Wrcester Center for the Performing Arts. 2013. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Brown, Matthew (April 28, 2010). "College of Pharmacy To Buy Crowne Plaza Property". Worcester Business Journal. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- "Gateway Park at WPI". Worcester Polytechnic Institute. 2013. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Kotsopoulos, Nick (March 17, 2010). "Hanover buys into CitySquare". Worcester Telegram & Gazette. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- "Front St. connection planned by end of year in Worcester". Worcester Telegram & Gazette. December 13, 2012. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- "Baker-Polito Administration Celebrates 75 Roadway and Bridge Projects Impacting 77 Communities Across Central Massachusetts". www.mass.gov. July 13, 2017. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- "Baker-Polito Administration Highlights 90 Road and Bridge Projects Across 61 Northeast Massachusetts Communities". www.mass.gov. July 18, 2017. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- Fabos, A., Pilgrim, M., Said-Ali, M., Krahe, J., Ostiller, Z. 2015. Understanding refugees in Worcester, MA. Mosakowski Institute for Public Enterprise.

- Jones-D'Agostino, Steven (September 3, 2013). "Worcester's Canal District Banks On National Park Designation". GoLocalWorcester. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Baker-Polito Administration Announces $400K MassWorks Award for Worcester". www.mass.gov. November 2, 2018. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- United States Department of Agriculture. United States National Arboretum. USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map [archived March 3, 2015; Retrieved February 19, 2015].

- "Daily temperature records". National Weather Service. 2007. Archived from the original on May 12, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

- "Daily temperature records". National Weather Service. 2007. Archived from the original on May 12, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

- "Threaded Extremes". Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- "Station Name: MA WORCESTER RGNL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- "CENSUS OF POPULATION AND HOUSING (1790–2000)". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- American FactFinder . Factfinder2.census.gov. Retrieved on August 2, 2013.

- "Worcester (city), Massachusetts". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012.

- "Massachusetts – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- "SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 17, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- "ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- "HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- "Considering Worcester's Charter" (PDF). Worcester Regional Research Bureau. April 20, 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved June 17, 2004.

- Santucci, Jack (April 2018). "Evidence of a winning-cohesion tradeoff under multi-winner ranked-choice voting". Electoral Studies. 52: 128–138. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2017.11.003. ISSN 0261-3794. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- "Worcester, MA History". City of Worcester, Massachusetts. 2007. Archived from the original on March 4, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- American Experience | Emma Goldman | People & Events Archived July 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. PBS. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- "Ku Klux Clan Rallies in Worcester: October 19, 1924". Mass Moments. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- "The Commonwealth of Massachusetts: Enrollment Breakdown as of October 19, 2016 (pg 18)" (PDF). Massachusetts Elections Division. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- "Personnel—EMTP Chief of EMS". UMassMemorial Emergency Medical Services. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

…one of the first EMTs to staff the Worcester City Hospital ambulance service when it began providing care to the community in 1977.

- "Emergency Response". UMassMemorial Emergency Medical Services. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

…one of the few remaining EMS services in Massachusetts that maintain a two-paramedic crew configuration on our advanced life support ambulances.

- "FAQ's". UMassMemorial Emergency Medical Services. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- "9-1-1 Call Taking". UMassMemorial Emergency Medical Services. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- "Wall & Main: Worcester's rising as a startup hub". Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- "The next start-up hubs". Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- Novinson, Michael. " Index: Central Mass. #5 in U.S. For Owning Rental Property." Worcester Business Journal. October 8, 2013.

- Hanson, Melissa (November 1, 2016). "Worcester to receive $2.3 million boost to create more walkable downtown". MassLive.com. Advance Publications. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- Dumcius, Gintautus (January 6, 2017). "Mass. Gov. Charlie Baker signs bill allowing unused Worcester land to become biomanufacturing site". MassLive.com. Advance Publications. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- Lee, Brian (November 9, 2017). "Land deal signed for Worcester biomanufacturing site". Telegram & Gazette. GateHouse Media. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- "City of Worcester 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). worcesterma.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- "Worcester – Enrollment/Indicators". Massachusetts Department of Education. 2019. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- "Worcester – Directory Information". Massachusetts Department of Education. 2007. Archived from the original on July 5, 2007. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Williams, Michelle (June 8, 2015). "State awards $4.48 million to school turnaround efforts in Springfield, Worcester". MassLive.com. Advance Publications. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- "Becker Game Design Program Ranked Top 10". Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- "National Liberal Arts College Rankings". Archived from the original on August 21, 2016.

- "About". Quinsigamond Community College. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- "America's Best Graduate Schools 2007: Top Medical Schools – Primary Care". US News & World Report. 2007. Archived from the original on March 6, 2007. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Hopewell, Brian: Archived April 19, 2007, at Archive.today College Gap Year website, Dynamy.

- DPW Parks, Recreation & Cemetery – Salisbury Park Archived July 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- "How do you say 'Worcester?'". College of the Holy Cross. 2013. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "Shrewbury Street: A Mecca for the Diverse Palate". GoLocalWorcester. 2013. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "History". the Canal District of Worcester. 2013. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "About Mechanics Hall". Mechanics Hall. 2013. Archived from the original on October 8, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "Restoration". Worcester Center for the Performing Arts. 2013. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "The Worcester Youth Orchestras Founded in 1947 – Home". The Worcester Youth Orchestras Founded in 1947. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- Wormtown at 20 – Timeline of events Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Worcester Phoenix, June 19–26, 1998.

- Williamson, Chet (June 3, 2010). "Wormtown at 30". Worcester Magazine. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011.

- O'Connor, Andrew. A Wormtown Gimmick Archived November 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- "City Parks". City of Worcester, Massachusetts — Public Works and Park. 2007. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- "Worcester Art Museum". tfaoi.org. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- Edgers, Geoff (March 8, 2013). "Higgins Armory Museum to close". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- "CITY OF WORCESTER BREAKS GROUND FOR POLAR PARK". City of Worcester, MA. July 11, 2019. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- "PawSox announce plans to move to Worcester in 2021". NBC Sports Boston. August 17, 2018. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Worcester County Wildcats". Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- F.P. Rice "The Worcester of 1898"

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Worcester

- "Religion in Worcester County, 2010". 2010 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations & Membership Study, published by the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (ASARB). Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- About us Archived May 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Synagogue website. Accessed July 17, 2008.

- McAfee, Andrew Bryce (December 2015). "Digital History Display: A Legacy for TheWorcester Armenian Community". Worcester Polytechnic Institute Digital WPI. Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- "These Iraqi immigrants revere John the Baptist, but they're not Christians". Public Radio International. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- "GateHouse parent buys T&G — and its parent chain". Media Nation. 2014. Archived from the original on January 3, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- "WCCA TV 194". www.wccatv.com. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- "Ask the Rambler – What Is The Longest Road in the United States?". US Department of Transportation – Federal Highway Administration. January 18, 2005. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved March 2, 2007.

- "MBTA board OKs beefed up train service". Telegram.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- "Worcester Regional Airport Fact Sheet" (PDF). massport.com. Massachusetts Port Authority. July 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- Osborn, Lawrence A. (2009). "From Beauty to Despair: The Rise and Fall of the American State Mental Hospital". Psychiatric Quarterly. 80 (4): 219–231. doi:10.1007/s11126-009-9109-3. PMID 19633958. S2CID 11812547.

- "Sister Cities Directory: Worcester, Massachusetts". Sister Cities Intl. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

Further reading

- Dubay, Debby (2014). Worcester, Massachusetts: "The Heart of the Commonwealth." Atglen, PA: Schiffer, Publishing.

- Erskine, Margaret A. (1981). Heart of the Commonwealth: Worcester. Windsor Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89781-030-2.

- Flynn, Sean (2002). 3000 Degrees: The True Story of a Deadly Fire and the Men who Fought It. New York: Warner Books.

- Lincoln, William (1837). History of Worcester, Massachusetts, from its earliest settlement to September 1836. M. D. Phillips.

- Moynihan, Kenneth J. (2007). A History of Worcester, 1674–1848. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-234-5.

- Wall & Gray. 1871 Atlas of Massachusetts.

- Worcester Directory, Worcester, Mass.: Sampson & Murdock Co., 1920

- "From Bondage to Belonging: The Worcester Slave Narratives", B. Eugene McCarthy & Thomas L. Doughton, editors.

- Map of Massachusetts. USA. New England. Counties – Berkshire, Franklin, Hampshire and Hampden, Worcester, Middlesex, Essex and Norfolk, Boston – Suffolk, Plymouth, Bristol, Barnstable and Dukes (Cape Cod). Cities – Springfield, Worcester, Lowell, Lawrence, Haverhill, Newburyport, Salem, Lynn, Taunton, Fall River. New Bedford. These 1871 maps of the Counties and Cities are useful to see the roads and rail lines.

- Beers, D.G. 1872 Atlas of Essex County Map of Massachusetts Plate 5. Click on the map for a very large image. Also see map of 1872 Essex County Plate 7.