1820 United States presidential election

The 1820 United States presidential election was the ninth quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Wednesday, November 1, to Wednesday, December 6, 1820. Taking place at the height of the Era of Good Feelings, the election saw incumbent Democratic-Republican President James Monroe win re-election without a major opponent. It was the third and last United States presidential election in which a presidential candidate ran effectively unopposed. It was also the last election of a president from the revolutionary generation.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

235 members[lower-alpha 1] of the Electoral College 117 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 10.1%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

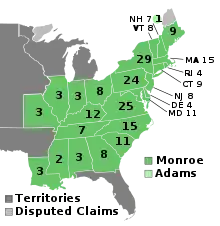

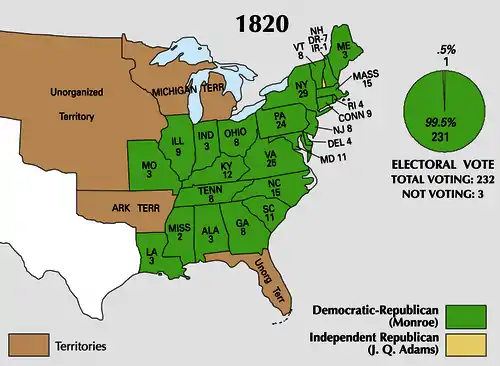

Presidential election results map. Green denotes states won by Monroe, light green denotes a New Hampshire elector William Plumer's vote for John Quincy Adams. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes cast by each state. Missouri's statehood status and subsequent electoral votes were disputed. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Monroe and Vice President Daniel D. Tompkins faced no opposition from other Democratic-Republicans in their quest for a second term. The Federalist Party had fielded a presidential candidate in each election since 1796, but the party's already-waning popularity had declined further following the War of 1812. Although able to field a nominee for vice president, the Federalists could not put forward a presidential candidate, leaving Monroe without organized opposition.

Monroe won every state and received all but one of the electoral votes. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams received the only other electoral vote, which came from faithless elector William Plumer. Nine different Federalists received electoral votes for vice president, but Tompkins won re-election by a large margin. No other post-Twelfth Amendment presidential candidate has matched Monroe's share of the electoral vote. Monroe and George Washington remain the only presidential candidates to run without any major opposition. Monroe's victory was the last of six straight victories by Virginians in presidential elections (Jefferson twice, Madison twice, and Monroe twice). Monroe was the first presidential candidate to receive at least 200 electoral votes in a victorious campaign.

Background

Despite the continuation of single party politics (known in this case as the Era of Good Feelings), serious issues emerged during the election in 1820. The nation had endured a widespread depression following the Panic of 1819 and momentous disagreement about the extension of slavery into the territories was taking center stage. Nevertheless, James Monroe faced no opposition party or candidate in his re-election bid, although he did not receive all of the electoral votes (see below).

Massachusetts was entitled to 22 electoral votes in 1816, but cast only 15 in 1820 by reason of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which made the region of Maine, long part of Massachusetts, a free state to balance the pending admission of slave state Missouri. In addition, Pennsylvania, Tennessee and Mississippi also cast one fewer electoral vote than they were entitled to, as one elector from each state died before the electoral meeting. Consequently, this meant that Mississippi cast only two votes, when any state is always entitled to a minimum of three.

Mississippi, Illinois, Alabama and Missouri participated in their first presidential election in 1820, Missouri with controversy, since it was not yet officially a state (see below). No new states would participate in American presidential elections until 1836, after the admission to the Union of Arkansas in 1836 and Michigan in 1837 (after the main voting, but before the counting of the electoral vote in Congress).[2]

Nominations

Democratic-Republican Party nomination

| James Monroe | Daniel D. Tompkins | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5th President of the United States (1817–1825) |

6th Vice President of the United States (1817–1825) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Since President Monroe's re-nomination was never in doubt, few Republicans bothered to attend the nominating caucus in April 1820. Only 40 delegates attended, with few or no delegates from the large states of Virginia, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. Rather than name the president with only a handful of votes, the caucus declined to make a formal nomination. Richard M. Johnson offered the following resolution: "It is inexpedient, at this time, to proceed to the nomination of persons for the offices of President and Vice President of the United States." After debate, the resolution was unanimously adopted, and the meeting adjourned. President Monroe and Vice President Daniel D. Tompkins thus became de facto candidates for re-election.

In the run-up to the caucus, Tompkins made another run for his former post of Governor of New York, leading to potential replacements being informally discussed among the party leadership. The matter was ultimately rendered moot when Tompkins lost the election shortly before the nominating caucus took place, and though some within the party remained dissatisfied with Tompkins' performance as Vice President, the role was not considered important enough to be worth a formal nomination process after his ability to continue in the office was confirmed.

| Presidential Ballot | Vice Presidential Ballot | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| James Monroe | 40 | Daniel D. Tompkins | 40 |

General election

Campaign

Effectively there was no campaign, since there was no serious opposition to Monroe and Tompkins.

Disputes

On March 9, 1820, Congress had passed a law directing Missouri to hold a convention to form a constitution and a state government. This law stated that "the said state, when formed, shall be admitted into the Union, upon an equal footing with the original states, in all respects whatsoever."[3] However, when Congress reconvened in November 1820, the admission of Missouri became an issue of contention. Proponents claimed that Missouri had fulfilled the conditions of the law and therefore was a state; detractors contended that certain provisions of the Missouri Constitution violated the United States Constitution.

By the time Congress was due to meet to count the electoral votes from the election, this dispute had lasted over two months. The counting raised a ticklish problem: if Congress counted Missouri's votes, that would count as recognition that Missouri was a state; on the other hand, if Congress failed to count Missouri's vote, it would count as recognition that Missouri was not a state. Knowing ahead of time that Monroe had won in a landslide and that Missouri's vote would therefore make no difference in the final result, the Senate passed a resolution on February 13, 1821 stating that if a protest were made, there would be no consideration of the matter unless the vote of Missouri would change who would become president. Instead, the President of the Senate would announce the final tally twice, once with Missouri included and once with it excluded.[4]

The next day this resolution was introduced in the full House. After a lively debate, it was passed. Nonetheless, during the counting of the electoral votes on February 14, 1821, an objection was raised to the votes from Missouri by Representative Arthur Livermore of New Hampshire. He argued that since Missouri had not yet officially become a state, it had no right to cast any electoral votes. Immediately, Representative John Floyd of Virginia argued that Missouri's votes must be counted. Chaos ensued, and order was restored only with the counting of the vote as per the resolution and then adjournment for the day.[5]

Results

Popular vote

The Federalists received a small amount of the popular vote despite having no electoral candidates. Even in Massachusetts, where the Federalist slate of electors was victorious, the electors cast all of their votes for Monroe. This was the first election in which the Democratic-Republicans won in Connecticut and Delaware.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a) | Electoral vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| James Monroe (incumbent) | Democratic-Republican | Virginia | 87,343 | 80.61% | 228/231(c) |

| No candidate | Federalist | N/A | 17,465 | 16.12% | 0 |

| DeWitt Clinton | Democratic-Republican | New York | 1,893 | 1.75% | 0 |

| John Quincy Adams | Democratic-Republican | Massachusetts | (b) | (b) | 1 |

| Unpledged electors | None | N/A | 1,658 | 1.53% | 0 |

| Total | 108,359 | 100.0% | 229/232(c) | ||

| Needed to win | 115/117(c) | ||||

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005.

Source (Popular Vote): A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825[6]

(a) Only 15 of the 24 states chose electors by popular vote.

(b) Adams received his vote from a faithless elector.

(c) There was a dispute as to whether Missouri's electoral votes were valid, due to the timing of its assumption of statehood. The first figure excludes Missouri's votes and the second figure includes them.

Electoral vote

The sole electoral vote against Monroe came from William Plumer, an elector from New Hampshire and former United States senator and New Hampshire governor. Plumer cast his electoral ballot for Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. While legend has it this was to ensure that George Washington would remain the only American president unanimously chosen by the Electoral College, that was not Plumer's goal. In fact, Plumer simply thought that Monroe was a mediocre president and that Adams would be a better one.[7] Plumer also refused to vote for Tompkins for Vice President as "grossly intemperate", not having "that weight of character which his office requires," and "because he grossly neglected his duty" in his "only" official role as President of the Senate by being "absent nearly three-fourths of the time";[8] Plumer instead voted for Richard Rush.

Even though every member of the Electoral College was pledged to Monroe, there were still a number of Federalist electors who voted for a Federalist vice president rather than Monroe's running mate Daniel D. Tompkins: those for Richard Stockton came from Massachusetts, while the entire Delaware delegation voted for Daniel Rodney for Vice President, and Robert Goodloe Harper's vice presidential vote was cast by an elector from his home state of Maryland. In any case, these breaks in ranks were not enough to deny Tompkins a substantial electoral college victory.

Monroe's share of the share of the electoral vote has not been exceeded by any candidate since, with the closest competition coming from Franklin D. Roosevelt's landslide 1936 victory.

Only Washington, who won the vote of each presidential elector in the 1789 and 1792 presidential elections, can claim to have swept the Electoral College.

Washington's campaigns took place prior to the 1804 ratification of the Twelfth Amendment instituting the current system, where each member of the Electoral College casts one vote for president and one vote for vice president.

Under the original system, each elector cast two votes, with no distinction being made between the votes for president and for vice president. Thus, in both of his campaigns, this meant Washington won the maximum number of electoral votes possible for any candidate, as opposed to winning 50% of the total electoral votes cast.

| Vice presidential candidate | Party | State | Electoral vote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel D. Tompkins | Democratic-Republican | New York | 215/218(a) |

| Richard Stockton | Federalist | New Jersey | 8(b) |

| Daniel Rodney | Federalist | Delaware | 4(b) |

| Robert Goodloe Harper | Federalist | Maryland | 1(b) |

| Richard Rush | Federalist | Pennsylvania | 1(b) |

| Total | 229/232(a) | ||

| Needed to win | 115/117(a) | ||

Source: "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005.

(a) There was a dispute over the validity of Missouri's electoral votes, due to the timing of its assumption of statehood. The first figure excludes Missouri's votes and the second figure includes them.

(b) These votes are from electors who voted for a Federalist vice president rather than Monroe's running mate Daniel D. Tompkins; combined, these votes represent only 5.6% of the electoral vote.

Results by State

Elections in this period were vastly different from modern day Presidential elections. The actual Presidential candidates were rarely mentioned on tickets and voters were voting for particular electors who were pledged to a particular candidate. There was sometimes confusion as to who the particular elector was actually pledged to. Results are reported as the highest result for an elector for any given candidate. For example, if three Monroe electors received 100, 50, and 25 votes, Monroe would be recorded as having 100 votes. Confusion surrounding the way results are reported may lead to discrepancies between the sum of all state results and national results.

In Massachusetts, Federalist electors won 62.06% of the vote. However, only 7,902 of these votes went to Federalist electors who did not cast their votes for Monroe (this being most likely because these Federalist electors lost). Similarly, In Kentucky, 1,941 ballots were cast for an elector labelled as Federalist who proceeded to vote for Monroe. All of the Federalist Monroe votes have been placed in the Federalist column, as the Federalist party fielded no presidential candidate and therefore it is likely these electors simply cast their votes for Monroe because the overwhelming majority he achieved made their votes irrelevant.

| James Monroe

Democratic-Republican |

No Candidate

Federalist |

Others | Not Cast | Margin | Citation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Electoral Vote | # | % | Electoral Votes | # | % | Electoral Votes | # | % | Electoral Votes | # | # | % | |

| Alabama | 3 | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [9] |

| Connecticut | 9 | 3,871 | 84.17% | 9 | 728 | 15.83% | - | - | - | - | - | 3,143 | 68.34% | [10] |

| Delaware | 4 | - | - | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [9] |

| Georgia | 8 | - | - | 8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [9] |

| Illinois | 3 | 940 | 65.14% | 3 | - | - | - | 503 | 34.86% | - | - | 749 | 51.91% | [11] |

| Indiana | 3 | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [9] |

| Kentucky | 12 | 2,729 | 58.44% | 12 | 1,941 | 41.56% | - | - | - | - | - | 788 | 16.88% | [12] |

| Louisiana | 3 | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [9] |

| Maine | 9 | 9,282 | 95.83% | 9 | - | - | - | 404 | 4.17% | - | - | 8,878 | 91.39% | [13] |

| Maryland | 11 | 4,167 | 82.61% | 11 | 877 | 17.39% | - | - | - | - | - | 3,290 | 65.22% | [14] |

| Massachusetts | 15 | 17,619 | 36.85% | 15 | 29,675 | 62.06% | - | 523 | 1.09% | - | - | -12,056 | -25.21% | [15] |

| Mississippi | 3 | 490 | 100% | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 490 | 100% | [16] |

| Missouri | 3 | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [9] |

| New Hampshire | 8 | 9,459 | 98.96% | 7 | 99 | 1.04% | - | - | - | 1 | - | 9,360 | 97.92% | [17] |

| New Jersey | 8 | 4,102 | 99.88% | 8 | 5 | 0.12% | - | - | - | - | - | 4,097 | 99.76% | [18] |

| New York | 29 | - | - | 29 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [9] |

| North Carolina | 15 | 3,340 | 99.11% | 15 | 1 | 0.03% | - | 29 | 0.86% | - | 3,311 | 98.25% | [19] | |

| Ohio | 8 | 7,164 | 99.53% | 8 | - | - | - | 34 | 0.47% | - | - | 7,130 | 99.06% | [18] |

| Pennsylvania | 24 | 30,313 | 94.12% | 23 | - | - | - | 1,893 | 5.88% | - | 1 | 28,420 | 88.24% | [20] |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 724 | 100% | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 724 | 100% | [21] |

| South Carolina | 11 | - | - | 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [9] |

| Tennessee | 7 | 1,336 | 80.34% | 6 | - | - | - | 327 | 19.66% | - | 1 | 1,009 | 60.68% | [22] |

| Vermont | 8 | - | - | 8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [9] |

| Virginia | 25 | 4,320 | 100% | 25 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4,320 | 100% | [23] |

Electoral college selection

| Method of choosing Electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| Each Elector appointed by state legislature | |

| Each Elector chosen by voters statewide | |

| State divided into electoral districts, with one Elector chosen per district by the voters of that district |

|

| Two Electors chosen by voters statewide and one Elector chosen per Congressional district by the voters of that district |

See also

Footnotes

- Electors were elected to all 235 apportioned positions; however, three electors (from Mississippi, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania) pledged to the Monroe/Tompkins ticket died before the Electoral College convened and were not replaced, bringing the total number of electoral votes cast to 232.

- All but one of the voting electors were pledged to the Monroe/Tompkins ticket, though an elector from New Hampshire defected by voting for John Quincy Adams for President and Richard Rush for Vice President. An additional 13 electors voted for Monroe for President but various Federalist candidates for Vice President.

References

- "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press.

- Election of 1820

- United States Congress (1820). United States Statutes at Large. Act of March 6, ch. 23, vol. 3. pp. 545–548. Retrieved August 9, 2006.

- United States Congress (1821). Senate Journal. 16th Congress, 2nd Session, February 13. pp. 187–188. Retrieved July 29, 2006.

- Annals of Congress. 16th Congress, 2nd Session, February 14, 1821. Gales and Seaton. 1856. pp. 1147–1165. Retrieved July 29, 2006.CS1 maint: others (link)

- http://elections.lib.tufts.edu/catalog?commit=Limit&f%5Belection_type_sim%5D%5B%5D=General&f%5Boffice_id_ssim%5D%5B%5D=ON056&page=2&q=1820&range%5Bdate_sim%5D%5Bbegin%5D=1820&range%5Bdate_sim%5D%5Bend%5D=1820&search_field=all_fields&utf8=%E2%9C%93

- Turner (1955) p 253

- "Daniel D. Tompkins, 6th Vice President (1817-1825)" United States Senate web site.

- "Presidential Election of 1820". 270toWin.com. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

Bibliography

- Turner, Lynn W. (September 1955). "The Electoral Vote against Monroe in 1820—An American Legend". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. Organization of American Historians. 42 (2): 250–273. doi:10.2307/1897643. JSTOR 1897643.

- "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. Retrieved March 20, 2005.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1820. |

- United States presidential election of 1820 at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Presidential Elections of 1816 and 1820: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns, 1787-1825

- Election of 1820 in Counting the Votes Archived October 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine