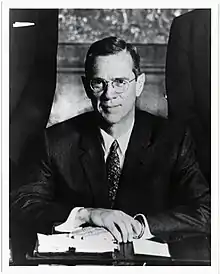

William McChesney Martin

William McChesney Martin Jr. (December 17, 1906 – July 27, 1998) was the ninth and longest-serving Chairman of the United States Federal Reserve Bank, serving from April 2, 1951, to January 31, 1970, under five presidents. Martin, who once considered becoming a Presbyterian minister, was described by a Washington journalist as "the happy Puritan".[1]

Bill Martin | |

|---|---|

| |

| 9th Chair of the Federal Reserve | |

| In office April 2, 1951 – February 1, 1970 | |

| President | Harry Truman Dwight Eisenhower John F. Kennedy Lyndon Johnson Richard Nixon |

| Deputy | Canby Balderston James Robertson |

| Preceded by | Thomas McCabe |

| Succeeded by | Arthur F. Burns |

| Member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors | |

| In office April 2, 1951 – February 1, 1970 | |

| President | Harry Truman Dwight Eisenhower John F. Kennedy Lyndon Johnson Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Thomas B. McCabe |

| Succeeded by | Arthur F. Burns |

| President of the New York Stock Exchange | |

| In office May 1938 – May 1941 | |

| Preceded by | Charles R. Gay |

| Succeeded by | Emil Schram |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William McChesney Martin Jr. December 17, 1906 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | July 27, 1998 (aged 91) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Education | Yale University (BA) Columbia University |

Early life

William McChesney Martin Jr. was born to William McChesney Martin Sr. and Rebecca Woods. Martin's connection to the Federal Reserve was forged through his family heritage. In 1913, Martin's father was summoned by President Woodrow Wilson and Senator Carter Glass to help write the Federal Reserve Act that would establish the Federal Reserve System on December 23 that same year. His father later served as a governor and then president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Martin was a graduate of Yale University, where his formal education was in English and Latin rather than finance. However, he still maintained an intense interest in business through his father. His first job after graduation was at the St. Louis brokerage firm of A. G. Edwards & Sons, where he became a full partner after only two years. From there, Martin's rapid rise in the financial world landed him in 1931 a seat on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), just two years after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 at the outset of the Great Depression. Martin pursued graduate study in Economics at Columbia University from 1931 to 1937; however, he did not receive a degree.[2] During the early part of that decade, Martin's work towards increasing regulation of the stock market led to his election to the NYSE's board of governors in 1935. There, he worked with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to reestablish confidence in the stock market and prevent future crashes. He eventually became president of the New York Stock Exchange at age 31, leading newspapers to label him the "boy wonder of Wall Street." Like his tenure as governor on the exchange, Martin's presidency focused on cooperating with the SEC to increase regulation of the exchange.

During World War II he was drafted into the United States Army as a private.[3] There he supervised the disposal of raw materials on the Munitions Allocation Board. He was also a liaison between the Army and Congress and the supervisor of the lend-lease program with the Soviet Union.

Career

Head of the Export-Import Bank

Martin's return to civilian life was also a return to the financial world, but this time it was on the side of the federal government. Harry S. Truman, a fellow Democrat, appointed Martin head of the Export-Import Bank, which he operated for three years (1946-1949). It was at this institution that he was publicly viewed as a "hard banker". He insisted that loans be sound, secure investments; on that principle he opposed the State Department on multiple occasions for making loans that he saw as being politically motivated. On those grounds he would not permit the Export-Import Bank to be used as a fund for international relief.

Martin finished his career with the Export-Import bank when he was called to the Treasury to be the assistant secretary for monetary affairs. Martin had been with the Treasury for about two years when its conflict with the Federal Reserve reached its climax. During the period immediately preceding the final negotiations with the Fed, Secretary of the Treasury John W. Snyder went into the hospital. Under these circumstances, Martin became the head negotiator for the Treasury. From the Treasury's perspective, Martin was a valuable representative. He had a thorough understanding of the Federal Reserve System and of financial markets; furthermore, he was viewed as an ally of Truman, who strongly opposed Fed independence. During negotiations, Martin reestablished communication between the Treasury and Fed, forbidden under Snyder.

Chairman of the Federal Reserve

With Robert Rouse, Woodlief Thomas, and Winfield Riefler of the Fed, Martin negotiated the 1951 Accord. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and Secretary Snyder accepted the Accord and its compromises and it was approved by both institutions. The Chairman of the Board of Governors at the time of ratification was Thomas B. McCabe (1893–1982), who would officially resign from his position just six days after the statement of the Accord was released. The Truman Administration saw the resignation of McCabe as the perfect opportunity to recapture the Fed almost immediately after it had supposedly broken away. Truman selected Martin to be the next Chairman of the Board of Governors, and the Senate approved his appointment on March 21, 1951.

Contrary to Truman's expectations, however, Martin guarded the Fed's independence, not just through Truman's administration but also through the four administrations that would follow. To the present day, his term as chairman is the longest term the board of governors has seen. Over nearly two decades, Martin would achieve global recognition as a central banker. He was able to pursue independent monetary policies while still paying heed to the desires of various administrations. Although the objectives of Martin's monetary policy were low inflation and economic stability, he rejected the idea that the Fed could pursue its policies through the targeting of a single indicator (an example of oversimplification) and instead made policy decisions by examining a wide array of economic information. As chairman, he institutionalized this approach within the proceedings of the FOMC, gathering the opinions of all governors and presidents within the System before making decisions. As a result, his decisions were often supported by unanimous votes on the FOMC. The job of the Federal Reserve, he famously said, is "to take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going,"[4][5] that is, raise interest rates just when the economy reaches peak activity after a recession.

Martin was selected administrator-designate of the Emergency Stabilization Agency, part of a secret group created by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1958 that would serve in the event of a national emergency and that became known as the Eisenhower Ten.[6]

After the presidential election of 1960, Republican Party candidate Richard Nixon blamed his defeat on Martin's tight-money policies[7]

In 1966 he had prostate surgery.[8]

Externally, Martin was perceived to be the dominant decision-maker at the Fed but this is only a perception.[9] Throughout his tenure, he defended the right of the Fed to take actions that would sometimes conflict with presidential desires. He regularly asserted that the Fed is responsible to US Congress and not to the White House. Lacking confidence in Martin, Nixon expected him to resign at the outset of the new administration, but Martin to chose not to. Pursuing a tight money policy to clamp down on inflation, Martin in mid 1969 ran afoul of Nixon's concern that the Fed was in danger of tipping the nation into recession, a belief that had been publicly stated by conservative economist Milton Friedman. Two days after an Oct. 15, 1969, White House meeting at which Nixon confronted Martin over his tight-money policy, on which Martin declined to yield, the White House announced that Arthur Burns would replace Martin as chairman of the Federal Reserve on Feb. 1, 1970.[10]

William McChesney Martin Jr. ended his term as Chairman of the Board of Governors on January 30, 1970. On that day, his career in public service ended, but he continued to work, holding a variety of directorships of corporations and nonprofit institutions, such as the Rockefeller Brothers Fund.

Martin was an avid tennis player who said he tried to play tennis nearly every day on the tennis court located outside the Federal Reserve Board of Governors Building in Washington, D.C.[11] Martin would go on to serve as president of the National Tennis Foundation and chair of the International Tennis Hall of Fame after retiring from the Federal Reserve.[12]

He died of a heart attack at his home in Washington, D.C., on July 28, 1998, at the age of 91.[13]

Legacy

The 1974 Federal Reserve Annex next to the Eccles Building is named for him.

See also

References

- Hodgson, Godfrey (21 August 1998). "Obituary: William McChesney Martin". The Independent. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- "William McChesney Martin". www.NNDB.com. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- "Private Martin". New York Times. April 17, 1941.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory (December 23, 2007). "How to Avoid Recession? Let the Fed Work". The New York Times.

- Martin, William McChesney Jr. (October 19, 1955). "Address before the New York Group of the Investment Bankers Association of America". FRASER. p. 12. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

The Federal Reserve, as one writer put it, after the recent increase in the discount rate, is in the position of the chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up.

- "The Eisenhower Ten: William McChesney Martin Jr". CONELRAD.COM. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- Lowenstein, Roger (January 20, 2008). "Ben Bernanke - Federal Reserve Bank - Interest Rates - United States Economy - Recessions - Banking - Housing - Mortgages". Retrieved January 28, 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- "William Martin Has Surgery". New York Times. July 9, 1966.

- Granville, Kevin (April 7, 2015). "America's Endless War Over Money". Retrieved January 28, 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- Matusow, Allen J. (1998). Nixon's Economy: Booms, Busts, Dollars, & Votes. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-7006-0888-5. OCLC 37975682.

- "Federal Reserve Tennis Court".

- "William McChesney Martin".

- Melody Petersen (July 29, 1998). "William McChesney Martin, 91, Dies. Defined Fed's Role". New York Times.

Further reading

- Portions of this article are based on public domain text from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

- Bremner, Robert (2004). Chairman of the Fed: William McChesney Martin Jr. and the Creation of the American Financial System. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300105087.

- Meltzer, Allan H. (2009). A History of the Federal Reserve – Volume 2, Book 1: 1951–1969. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226520025.

- Meltzer, Allan H. (2009). A History of the Federal Reserve – Volume 2, Book 2: 1970–1986. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 685–743. ISBN 978-0226213514.

External links

- Digital collection of documents from the William McChesney Martin Jr. Papers at the Missouri History Museum

- Statements and Speeches of William McChesney Martin Jr.

- Calendar of William McChesney Martin Jr. from his time as Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas McCabe |

Chair of the Federal Reserve 1951–1970 |

Succeeded by Arthur F. Burns |