Bank of North America

The Bank of North America was a private national bank which served as the United States' first de facto central bank.[1] Chartered by the Continental Congress on May 26, 1781, and opened in Philadelphia on January 7, 1782,[2][3][4] it was based upon a plan presented by US Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris on May 17, 1781,[5] based on recommendations by Revolutionary era figure Alexander Hamilton. Failing to gain and maintain sufficient long term traction in that role, it was succeeded by the also privately held First Bank of the United States in 1791.

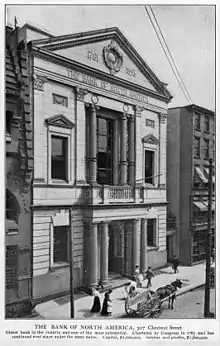

The bank's original building at 307 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia | |

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

| Industry | Financial institution |

| Fate | Merger |

| Successor | First Bank of the United States |

| Founded | December 31, 1781 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Founders | Robert Morris, Alexander Hamilton, William Bingham, et al |

| Defunct | 1929 |

| Headquarters | , |

Area served | Colonial America |

Key people | Tench Francis, Jr., First cashier; later known as the CEO |

History

Congressional charter

-Pennsylvania-6_Aug_1789.jpg.webp)

In May 1781 Alexander Hamilton revealed that he had recommended Robert Morris for the position of Superintendent of Finance of the United States the previous summer when the constitution of the Articles of Confederation-era executive was being solidified. Second, he proceeded to lay out a proposal for a national bank that would also serve as a de facto central bank. Morris, who had corresponded with Hamilton previously on the subject of funding the war, immediately drafted a legislative proposal based on Hamilton's suggestion and submitted it to the Congress. Morris persuaded Congress to charter the Bank of North America, the first private commercial bank in the United States.[7]

Stock offering

The original charter as outlined by Hamilton called for the disbursement of 1,000 shares priced at $400 each.[8] Benjamin Franklin purchased a single token share as a sign of good faith to Federalists and their new bank. Hamilton used his pseudonym "Publius" (later immortalized in the Federalist Papers advocating in the late 1780s for adoption of the United States Constitution) to endorse the bank.[9]

William Bingham, rumored to be the richest man in America after the Revolutionary War,[10] purchased 9.5% of the available shares.

The greatest share, however, 63.3%, was purchased on behalf of the United States government by Robert Morris using a gift in the form of a loan from France, and a loan from the Netherlands.[11] This had the effect of capitalizing the bank with large deposits of gold and silver coin and bills of exchange. He then issued new paper currency backed by this supply.[12]

Officers

Thomas Willing, a twice former mayor of Philadelphia and partner with Morris in an import-export firm (that included slaving), was named the bank's first president. He held that office from 1781–1791, being succeeded by John Nixon, and moving immediately on to become the first president of the First Bank of the United States, a position he held from 1791 to 1807.

Bank certificates

By 1783, Congress and several states including Massachusetts enacted legislation, allowing Americans to pay taxes with Bank of North America certificates,[13] giving them a crucial aspect of legal tender.

New York Stock Exchange

The Bank of North America along with the First Bank of the United States and the Bank of New York were the first shares traded on the New York Stock Exchange. The Bank of North America opened a Canadian affiliate in Montreal, Lower Canada on March 8, 1837.[14]

References

- Markham, Jerry W. (2002). A Financial History of the United States. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. p. 87. ISBN 978-0765607300. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Lewis, Lawrence, Jr. (1882). A History of the Bank of North America, the First Bank Chartered in the United States. J. B. Lippincott & Co. pp. 28, 35.

- Smith, Robert F. "Bank of North America". Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Michener, John H. (1906). "The Bank of North America, Philadelphia, a national bank, founded 1781; the story of its progress through the last quarter of a century, 1881–1906". New York: R. G. Cooke, Inc.: 37. HG21613.P54. Retrieved 17 March 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Establishing a National Bank". Journals of the Continental Congress. U.S. Government Printing Office. 20: 546–549. 1912. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Newman, Eric P. (28 November 2008). Early Paper Money of America (5th ed.). Iola, Wisconsin: KP Books. p. 364. ISBN 978-0896893269.

- Knox, John Jay (1900). Rhodes, Bradford; Youngman, Elmer Haskell (eds.). A History of Banking in the United States. B. Rhodes & Company. p. 40. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Alberts, Robert C. (1969). "The Golden Voyage: The Life and Times of William Bingham, 1752–1804". Houghton-Mifflin: 106. OCLC 563689565. Retrieved 17 March 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hamilton, Alexander; Syrett, Harold Coffin; Cooke, Jacob Ernest (1962). Syrett, Harold Coffin; Cooke, Jacob Ernest (eds.). The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231089050. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ALBERTS, ROBERT C (1969). The Golden Voyage. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 435.

- Alberts, Robert C. (1969). "The Golden Voyage: The Life and Times of William Bingham, 1752–1804". Houghton-Mifflin. OCLC 563689565. Retrieved 17 March 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dowgin, Christopher (2016). Sub Rosa. p. 83. ISBN 9780986261022.

- Alberts, Robert C. (1969). "The Golden Voyage: The Life and Times of William Bingham, 1752–1804". Houghton-Mifflin: 111. OCLC 563689565. Retrieved 17 March 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pound, Richard W. (2005). Fitzhenry and Whiteside Book of Canadian Facts and Dates. Fitzhenry and Whiteside. p. 188.

Further reading

- Rappleye, Charles (2010). Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 229–528. ISBN 978-1416570912.

External links

- The Bank of North America, Philadelphia, a National Bank, Founded 1781: The Story of Its Progress through the Last Quarter of a Century, 1881–1906, by Robert Grier Cooke Incorporated (1906).

- Debates and Proceedings of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania, on the Memorials Praying a Repeal of Suspension of the Law Annulling the Charter of the Bank (ed. Mathew Carey, 1786).

- A History of the Bank of North America, the First Bank Chartered in the United States, by Lawrence Lewis, Jr. (J. B. Lippincott & Co. 1882).

- Legislative and Documentary History of the Bank of the United States: Including the Original Bank of North America, by Matthew St. Clair Clarke and David A. Hall. This collection of documents was aimed to include the entire proceedings, debates, and resolutions of Congress relating to the Bank of North America, the First (1791–1811) Bank of the United States, and the Second (1816–1836) Bank of the United States. These documents were compiled four years before the closing of the Second Bank.

- Legislative and Documentary History of the Banks of the United States, from the Time of Establishing the Bank of North America, 1781, to October 1834; with Notes and Comments, by R. K. Moulton. An attempt to compile all the public documents considered to be essential in attaining a thorough knowledge of the national banking operations of the United States, from 1781 to 1834.