1964 California Proposition 14

California Proposition 14 was a November 1964 ballot proposition that amended the California state constitution, nullifying the Rumford Fair Housing Act.[1] Proposition 14 was declared unconstitutional by the California Supreme Court in 1966.[2] The decision of the California Supreme Court was affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967 in Reitman v. Mulkey.[3]

| Elections in California |

|---|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

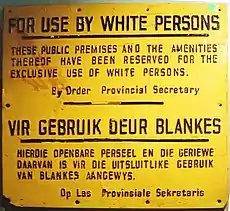

| Racial segregation |

|---|

|

| Segregation by region |

|

| Similar practices by region |

Political science research has tied white support for Proposition 14 to "racial threat theory", which holds that an increase in the racial minority population triggers a fearful and discriminatory response by the dominating racial majority.[4]

Circumstances Leading to Proposition 14

In 1948, the United States Supreme Court in Shelley v. Kraemer precluded judicial enforcement of racially restrictive housing covenants.[5] Prior to 1948, the California Real Estate Association (the eventual sponsor of Proposition 14) routinely promoted and enforced racially restrictive housing covenants to prevent family homes from ending up in the hands of minorities, particularly Negroes.[6]

Shortly following the 1948 court decision in Shelley, an item appeared in the California Real Estate magazine, a publication of the California Real Estate Association (the organization is currently named the California Association of Realtors) advocating an amendment to the United States Constitution that would overturn Shelley and constitutionally guarantee the legal enforcement of racially restrictive covenants throughout the United States.[7]

In advocating support for a federal constitutional amendment guaranteeing the legal enforcement of racially restrictive covenants, the California Real Estate Association publication stated that "millions of home owners of the Caucasian race have constructed or acquired homes in areas restricted against occupancy by Negroes. The practice of surrounding homes in such areas with the security of such restrictions has become a traditional element of value in home ownership throughout this nation."[8]

The publication further stated: "The recent decisions of the Supreme Court abovementioned have destroyed the values thus secured. The threat of occupancy by Negroes of property in such areas depreciates the value of all home properties and constitutes a direct deterrent to investment in the construction or acquisition of homes of superior quality whether large or small. The experience has been uniform that whenever and wherever Negroes have occupied homes in such areas this has not only depreciated values of the properties which they own, but has depreciated the values of all surrounding properties."[9]

In further support of the constitutional amendment, the publication stated: "Moreover, the prices of homes in such areas are well within the purchasing power of vast numbers of Negroes. These circumstances greatly aggravate the hazard to which such home owners are exposed. ... Additionally, the insistence of some Negroes upon moving into areas previously restricted exclusively to the occupancy of Caucasians will necessarily create racial tensions and antagonisms and do much harm to our national social structure."[10]

The federal constitutional amendment effort was unsuccessful, but the reasons for pursuing such an amendment provided insight into the underlying reasons for pursuing a future and similar protective state constitutional amendment in California.

Despite the court decision in Shelley, segregation in California continued. As an example, an insidious form of segregation known as blockbusting occurred in East Palo Alto. In 1954, a white resident sold his house to a black family. Almost immediately, agents of the California Real Estate Association began warning of a "Negro invasion" and even staged burglaries to panic white homeowners to sell at below-market prices. Those properties were then sold to Negroes at higher-than-market prices with real estate interests profiting from the transactions.[11]

The tipping point for the California Real Estate Association to pursue a state constitutional amendment in California was the enactment of the Rumford Fair Housing Act in 1963. In the minds of California Real Estate Association leaders, the Rumford Fair Housing Act directly threatened the financial interests of the real estate industry who came to see "the promotion, preservation, and manipulation of racial segregation as central -- rather than incidental or residual -- components of their profit generating strategies."[12]

Similar to Proposition 14, there have also been subsequent efforts by the real estate industry to promote ballot measures in California to generate more profits. Examples include the unsuccessful 2018 California Proposition 5[13] and 2020 California Proposition 19,[14] which has been criticized for not helping first-time homeowners who are disproportionately minorities[15] and for reinforcing racial inequity within California's tax system.[16]

Rumford Fair Housing Act

The Rumford Fair Housing Act was passed in 1963 by the California Legislature to help end racial discrimination by property owners and landlords who refused to rent or sell their property to "colored" people.[17] It was drafted by William Byron Rumford, the first African American from Northern California to serve in the legislature. The Act provided that landlords could not deny people housing because of ethnicity, religion, sex, marital status, physical handicap, or familial status.[18] Governor Ronald Reagan opposed this and other legislative attempts to enact fair housing.[19]

Proposition 14

In 1964, the California Real Estate Association (currently named the California Association of Realtors) sponsored an initiative constitutional amendment to counteract the effects of the Rumford Act.[20]

The initiative, numbered Proposition 14 when it was certified for the ballot, was to add an amendment (Cal. Const. art. I, § 26) to the constitution of California. This amendment would provide, in part, as follows:

Neither the State nor any subdivision or agency thereof shall deny, limit or abridge, directly or indirectly, the right of any person, who is willing or desires to sell, lease or rent any part or all of his real property, to decline to sell, lease or rent such property to such person or persons as he, in his absolute discretion, chooses.[21]

In California, housing segregation was rampant as a result of decades of racially discriminatory housing policies explicitly aimed at keeping people of color confined to urban ghettos and out of the expanding suburbs.[22] Proposition 14 attempted to re-legalize discrimination and associational privacy by landlords and property owners.

Ballot Arguments

The ballot argument in favor of Proposition 14 stated that the constitutional amendment "will guarantee the right of all home and apartment owners to choose buyers and renters of their property as they wish, without interference by State or local government." The argument further stated that "most owners of such property in California lost this right through the Rumford Act of 1963. It says they may not refuse to sell or rent their property to anyone for reasons of race, color, religion, national origin, or ancestry."[23]

The ballot argument against Proposition 14 stated that Proposition 14 "would write hate and bigotry into the Constitution." The argument further stated that Proposition 14 "would legalize and incite bigotry. At a time when our nation is moving ahead on civil rights, it proposes to convert California into another Mississippi or Alabama and to create an atmosphere for violence and hate."[24]

Endorsements

Following much publicity the proposition gained the endorsement of many large conservative political groups, including the John Birch Society and the California Republican Assembly. As these and other groups endorsed the proposal it became increasingly more popular and the petition to have the proposition added to the ballot garnered over one million signatures. This was more than twice the 480,000 signatures that were required.[25]

Los Angeles Times Endorsement

In endorsing Proposition 14, the Los Angeles Times stated: “One of man’s most ancient rights in a free society is the privilege of using and disposing of his private property in whatever manner he deems appropriate.” The editorial further stated: “But we do feel, and strongly, that housing equality cannot safely be achieved at the expense of still another basic right.”[26][27][28] According to the Los Angeles Times, the ability to discriminate against home buyers or renters by race, color, and creed was considered a "basic property right."[29]

In a letter-to-the-editor response to the Times' endorsement of Proposition 14, then-California Attorney General Stanley Mosk stated: “I oppose the segregation initiative. I oppose it because it sugar-coats bigotry with an appeal to generalities we can accept, while ignoring the specific problem that confronts us.”[30]

Heated campaign

The Proposition 14 campaign was heated and included several controversial comments from Edmund Brown who was the Governor of California at the time. Governor Brown stated that passage of Proposition 14 would put into California’s Constitution “a provision for discrimination of which not even Mississippi or Alabama can boast.”[31] Previously, Governor Brown had likened the campaign for Proposition 14 to “another hate binge which began more than 30 years ago in a Munich beer hall.”[32] In a letter to the editor response to several items published in the Los Angeles Times relating to Proposition 14, Governor Brown wrote: “I submit that it is not the Governor who is inflammatory. It is Proposition 14. And I submit that it is not the opponents of Proposition 14 who encourage the racists and bigots in this state, but those who support Proposition 14.”[33]

Martin Luther King Jr. visited California on multiple occasions to campaign against Proposition 14, saying its passage would be "one of the most shameful developments in our nation’s history."[34]

Election results

Proposition 14 appeared on the November 3, 1964 general election ballot in California. The ballot proposition easily passed with 65.39% support, receiving 4,526,460 votes in support and 2,395,747 votes against.[35]

Every county in the state voted in favor of Proposition 14 except for Modoc County, which rejected the measure by 19 votes.[36]

A 2018 study in the American Political Science Review found that white voters in areas which experienced massive African-American population growth between 1940 and 1960 were more likely to vote for Proposition 14. Political scientists have taken this as evidence for "racial threat theory", which holds that the rapid increase in a minority population triggers fears among the majority race population, leading the majority to impose higher levels of social control on the subordinate race.[4]

Unconstitutionality

Soon after Proposition 14 was passed, the federal government cut off all housing funds to California. Many also cited the proposition as one of the causes of the Watts Riots of 1965.[37]

With the federal housing funds cut off and with the support of Governor Pat Brown, the constitutionality of the measure was challenged soon afterward. In 1966, the California Supreme Court did not consider whether Proposition 14 was unconstitutional because it violated the equal protection and due process provisions of the California Constitution; instead, it held that Proposition 14 violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the federal Constitution.[38] Gov. Brown's stance proved controversial; later in 1966, he was defeated in his bid for re-election by Ronald Reagan. However, Reagan opposed both Proposition 14 and the Rumford Act, and stated that Proposition 14 was “not a wise measure.”[39] Reagan labeled the Rumford Act as an attempt "to give one segment of our population a right at the expense of the basic rights of all our citizens."[40]

However, the case continued. The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the California Supreme Court's decision in Reitman v. Mulkey (1967), holding that Proposition 14 was invalid because it violated the equal protection clause. The proposition was repealed by Proposition 7 in the November, 1974 election.[41]

Reitman established a significant precedent because it held that state assistance or encouragement of private discrimination violated the equal protection guarantee of the Fourteenth Amendment.

References

- Cal. Const. art. I, § 26 [adopted November 3, 1964, and repealed November 5, 1974].

- Mulkey v. Reitman (1966) 64 Cal. 2d 529

- Reitman v. Mulkey (1967) 387 U.S. 369

- Reny, Tyler T.; Newman, Benjamin J. (2018). "Protecting the Right to Discriminate: The Second Great Migration and Racial Threat in the American West". American Political Science Review. 112 (4): 1104–1110. doi:10.1017/S0003055418000448. ISSN 0003-0554. S2CID 149560682.

- Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (May 1948)

- Reft, Ryan (September 2, 2014). "Structured Unrest: The Rumford Act, Proposition 14, and the Systematic Inequality that Created the Watts Riots". Tropics of Meta.

- "Enforcement of Race Restrictions Through Constitutional Amendment Advocated". California Real Estate Magazine. September 1948.

- "Enforcement of Race Restrictions Through Constitutional Amendment Advocated". California Real Estate Magazine: 4. September 1948.

- "Enforcement of Race Restrictions Through Constitutional Amendment Advocated". California Real Estate Magazine: 4. September 1948.

- "Enforcement of Race Restrictions Through Constitutional Amendment Advocated". California Real Estate Magazine: 4. September 1948.

- Funabiki, Jon (November 2, 2017). "The myth and truth about housing segregation in the Bay Area". Renaissance Journalism.

- Self, Robert (2003). American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 265.

- Official Voter Information Guide, California General Election (November 6, 2018), pp. 34-39.

- Official Voter Information Guide, California General Election (November 3, 2020), pp. 38-43.

- The Greenlining Institute, 2020 California Ballot Propositions Guide [Proposition 19] (September 16, 2020).

- Kimberlin, Sara; Kitson, Kayla (September 2020). "Proposition 19: Creates a Complicated Property Tax Scheme and Reinforces Racial Inequities in California". California Budget & Policy Center. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- Health & Saf. Code, §§ 35700-35744 [added by Stats. 1963, Ch. 1853, § 2].

- Peniel E. Joseph (2006). The Black Power Movement: Rethinking the Civil Rights-Black Power Era. CRC Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-0-415-94596-7. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Pillar of Fire, Taylor Branch, p. 242

- "Proposition 14". Time Magazine. September 25, 1964. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- Cal. Const. art. I, § 26 [adopted November 3, 1964, and repealed November 5, 1974].

- Fleischer, Matthew (October 21, 2020). "How the L.A. Times helped write segregation into California's Constitution". Los Angeles Times.

- Ballot Pamphlet, Proposed Amendments to California Constitution with arguments to voters, General Election (November 3, 1964). California Secretary of State. p. 18.

- Ballot Pamphlet, Proposed Amendments to California Constitution with arguments to voters, General Election (November 3, 1964). California Secretary of State. p. 19.

- Robert O. Self (2003). American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. Princeton University Press. p. 168. ISBN 0-691-07026-1.

proposition 14 california 1964.

- "Decision on Housing Initiative". Los Angeles Times. February 2, 1964. p. K6.

- "Inflammatory Talk on Prop. 14". Los Angeles Times. August 31, 1964. p. A4.

- "Why Prop. 14 Deserves a YES Vote". Los Angeles Times. October 18, 1964. p. F6.

- Fleischer, Matthew (October 21, 2020). "How the L.A. Times helped write segregation into California's Constitution". Los Angeles Times.

- "Atty. Gen. Mosk Letter to the Editor". Los Angeles Times. February 15, 1964. p. B4.

- "Brown Assails Prop. 14 as 'Cudgel of Bigotry'". Los Angeles Times. October 8, 1964. p. 18.

- "Brown Hit for Attacks on Prop. 14". Los Angeles Times. August 28, 1964. p. 20.

- "Gov. Edmund Brown Letter to the Editor". Los Angeles Times. September 5, 1964. p. B4.

- Theoharis, Jeanne (September 10, 2018). "A National Problem". Boston Review. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- California Secretary of State, Statement of Vote November 3, 1964 General Election, p. 25.

- https://archive.org/details/castatem196264cali/page/n173/mode/2up.

- Alonso, Alex A. (1998). Rebuilding Los Angeles: A Lesson of Community Reconstruction (PDF). Los Angeles: University of Southern California.

- 64 Cal. 2d 529 (1966)

- "Prop. 14, Rumford Act Criticized by Reagan". Los Angeles Times. April 22, 1966. p. A8.

- Skelton, George (May 7, 2014) "Thank you, Donald Sterling, for reminding us how far we've come" Los Angeles Times

- "California Voter's Pamphlet, General Election, Nov. 5, 1974" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-11. Retrieved 2013-06-30.