History of Jakarta

Jakarta is Indonesia's capital and largest city. Located on an estuary of the Ciliwung River, on the northwestern part of Java, the area has long sustained human settlement. Historical evidence from Jakarta dates back to the 4th century CE, when it was a Hindu settlement and port. The city has been sequentially claimed by the Indianized kingdom of Tarumanegara, the Hindu Kingdom of Sunda, the Muslim Sultanate of Banten, and by Dutch, Japanese and Indonesian administrations.[1] The Dutch East Indies built up the area before it was taken during World War II by the Empire of Japan and finally became independent as part of Indonesia.

Jakarta has been known by several names. It was called Sunda Kelapa during the Kingdom of Sunda period and Jayakarta, Djajakarta or Jacatra during the short period of the Banten Sultanate. Thereafter, Jakarta evolved in three stages. The "old city", close to the sea in the north, developed between 1619 and 1799 during the era of the VOC. The "new city" to the south evolved between 1809 and 1942 after the Dutch government took over control of Batavia from the failed VOC whose charter expired in 1799. The third was the development of modern Jakarta since the proclamation of independence in 1945. Under the Dutch, it was known as Batavia (1619–1945), and was Djakarta (in Dutch) or Jakarta, during the Japanese occupation and the modern period.[2][3]

For a more detailed history of Jakarta before the proclamation of Indonesian independence, see Batavia, Dutch East Indies.

Early kingdoms (4th century AD)

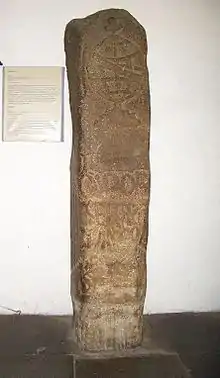

The coastal area and port of Jakarta in northern West Java has been the location of human settlement since the 4th century BCE Buni culture. The earliest historical record discovered in Jakarta is the Tugu inscription, which was discovered in Tugu sub-district, North Jakarta. It is among the oldest inscriptions in Indonesian history. The area was part of the Indianized kingdom of Tarumanagara.

In AD 397, King Purnawarman established Sunda Pura, located on the northern coast of West Java, as the new capital city for the kingdom.[4] The capital of Tarumanagara kingdom was most probably located somewhere between Tugu sub-district North Jakarta and Bekasi Regency West Java. Purnawarman left seven memorial stones across the area, including the present-day Banten and West Java provinces, consisting of inscriptions bearing his name.[5]

Kingdom of Sunda (669–1527)

After the power of Tarumanagara declined, its territories became part of the Kingdom of Sunda. According to the Chinese source, Chu-fan-chi, written by Chou Ju-kua in the early 13th Century, the Sumatra-based kingdom of Srivijaya ruled Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, and western Java (known as Sunda). The port of Sunda was described as strategic and thriving, with pepper from Sunda renowned for its supreme quality. The people of the area worked in agriculture and their houses were built on wooden piles.[6]

One of the ports at the mouth of a river was renamed Sunda Kelapa or Kalapa (Coconut of Sunda), as written in Hindu Bujangga Manik, manuscripts from a monk's lontar and one of the precious remnants of Old Sundanese literature.[7] The port served Pakuan Pajajaran (present day Bogor), the capital of the Sunda Kingdom. By the fourteenth century, Sunda Kelapa became a major trading port for the kingdom.

Accounts of 16th century European explorers make mention of a city called Kalapa, which apparently served as the primary port of a Hindu kingdom of Sunda.[1] In 1522, the Portuguese secured Luso Sundanese padrão, a political and economic agreement with the Sunda Kingdom, the authority of the port. In exchange for military assistance against the threat of the rising Islamic Javan Sultanate of Demak, Prabu Surawisesa, king of Sunda at that time, granted them free access to the pepper trade. Portuguese who were in the service of the sovereign made their homes in Sunda Kelapa.

Banten Sultanate (1527–1619)

To prevent Portuguese gaining a foothold on Java, Fatahillah, on behalf of the Demak attacked the Portuguese in Sunda Kelapa in 1527 and succeeded in conquering the harbour on 22 June, after which Sunda Kelapa was renamed Jayakarta.[1][8] Later, the port became a part of the Banten Sultanate, located west from Jayakarta.

By the late 16th century, Jayakarta was under the rule of the Sultanate of Banten. Prince Jayawikarta, a follower of the Sultan of Banten, established a settlement on the west banks of the Ciliwung River, erecting a military post to control the port at the mouth of the river.[9]

Dutch Batavia (1610-1942)

Dutch East India Company (1610–1800)

Dutch mercantile activity to East Indies commenced in 1595. Over the next 25 years there was contention between the Dutch and British on the one hand, and between the Sultanate of Banten and Prince Jayawikarta on the other.

In 1602, the Dutch government granted a monopoly on Asian trade to the Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC); literally[10] United East Indian Company).[11]:26[12]:384–385 In 1603, the first permanent Dutch trading post in Indonesia was established in Bantam, West Java. In 1610, Prince Jayawikarta granted permission to Dutch merchants to build a wooden godown and houses on the east bank of the Ciliwung River, opposite to Jayakarta. This outpost was established in 1611.[13]:29

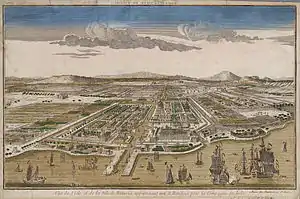

The rivalry was ultimately resolved in 1619, when the Dutch established a closer relationship with Banten and militarily intervened at Jayakarta, where they assumed control of the port after destroying the existing city.[14] The new city built on the site was officially named as Batavia on January 18, 1621,[14] from which the Dutch East Indies eventually ruled the entire region. Batavia under VOC control was essentially a Company Town, under the authority of a governor-general in Batavia and a board of directors in Amsterdam that served the Dutch merchants in the region, predominantly the spice trade between Europe and the Moluccas.[15] The administrative center of this new town is the Batavia Castle.

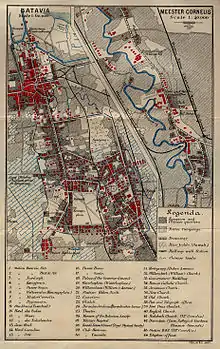

During the era of the VOC, Batavia was centered on the so-called Benedenstad or "Lower City". It consisted of the walled Kota, the older harbor at Sunda Kelapa, and the Chinese quarter at Glodok. In the middle of 18th century, Batavia also included the outskirts area along the canal of the Molenvliet (now Jalan Gajah Mada and Jalan Hayam Wuruk), the Noordwijk (now Jalan Juanda), the Rijswijk (now Jalan Veteran), along Gunung Sahari, and Jacatraweg (Jalan Pangeran Jayakarta). Also included were the markets at Tanah Abang and Senen, Jakarta's oldest markets.[15]

Batavia was under VOC control until the Company went bankrupt and its charter expired in 1799.

Dutch East Indies (1800–1942)

After the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) went bankrupt and was dissolved in 1800, the Batavian Republic nationalized its debts and possessions, expanding all of the VOC's territorial claims into a fully-fledged colony named the Dutch East Indies. Batavia evolved from the site of the company's regional headquarters into the capital of the colony. The city gradually expanded to the south.[15]

During the period, administrative buildings were relocated to the area then known as Weltevreden, e.g. south of the Koningsplein, the Waterlooplein and Rijswijk (Jalan Veteran). The area, then known as Weltevreden, which include the Koningsplein, Rijswijk, Noordwijk, Tanah Abang, Kebon Sirih, and Prapatan became a popular residential, entertainment and commercial district for the European colonial elite. The name Weltevreden lingered until 1931 when it officially became known as Batavia Centrum (Central Batavia).[15]

The period also saw development of the Pasar Baru market in the 1820s, the completion of Tanjung Priok port in 1886, the development of Menteng and Gondangdia garden city in the 1910s, and the inclusion of Meester Cornelis (now Jatinegara) into Jakarta in 1935.[15]

Japanese occupation (1942–1945)

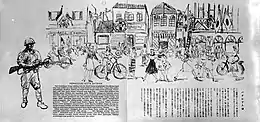

On 5 March 1942, Batavia fell to the Japanese. The Dutch formally surrendered to the Japanese occupation forces on 9 March 1942, and rule of the colony was transferred to Japan. The city was renamed Jakarta (officially ジャカルタ特別市 Jakaruta tokubetsu-shi, Special Municipality of Jakarta, in accordance with the special status that was assigned to the city).

To strengthen its position in Indonesia, the Japanese government issued Act No. 42 1942 as part of the "Restoration of the Regional Administration System". This act divided Java into several Syuu ("Resident Administration" or Karesidenan) that were each led by a Bupati (Regent). Each Syuu was divided into several Shi ("Municipality" or Stad Gemeente) that were led by Wedanas ("District Heads"). Below a Wedana was a Wedana Assistant ("Sub-district Head"), who, in turn, oversaw a Lurah ("Village Unit Head"), who, in turn, was responsible over a Kepala Kampung ("Kampung Chief").

A schichoo ("Mayor") was superior to all of these officials, following the law created by the Guisenken ("Head of the Japanese Imperial Administration"). The effect of this system was a "one-man rule" structure with no councils or representative bodies. The first schichoo of Jakarta was Tsukamoto and the last was Hasegawa.[16]

The economic situation and the physical condition of Indonesian cities deteriorated during the occupation, including Jakarta. Beautiful colonial buildings and hotels were converted into military barracks. Many buildings were vandalized, as metal was needed for the war, and many iron statues from the Dutch colonial period were taken away by the Japanese troops. Among the destroyed colonial landmarks during the Japanese occupation were the statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen at Waterlooplein.

In 1943, the Japanese Imperial administration slightly revised the administration of Jakarta by adding a special counseling body. This agency was composed of twelve local Javanese leaders who were regarded as loyal to the Japanese; among them were Suwiryo (who became the vice for Jakarta's schichoo) and Dahlan Abdullah.[16]

National revolution era (1945–1949)

After the collapse of Japan in 1945, the area went through a period of transition and upheaval during the Indonesian national struggle for independence. During the Japanese occupation and from the perspective of the Indonesian nationalists who declared independence on 17 August 1945, the city was renamed Jakarta.[17] After the war, the Dutch name Batavia was internationally recognized until full Indonesian independence was achieved on 27 December 1949 and Jakarta was officially proclaimed the national capital of Indonesia.[17]

Following the surrender of the Japanese, Indonesia declared its independence on 17 August 1945. The proclamation was enacted at Jalan Pegangsaan Timur No. 56 (now Jalan Proklamasi), Central Jakarta, with Suwiryo acting as the committee chairman. Suwiryo was recognised as the first mayor of Jakarta Tokubetsu Shi. The position was soon altered to Pemerintah Nasional Kota Jakarta ("Jakarta City National Administration").

On 19 September 1945, Sukarno held his Indonesian independence and anti-colonialism/imperialism speech, during Rapat Akbar or grand meeting at Lapangan Ikada, now the Merdeka Square. The grand meeting would start a period of national revolution in Indonesia.[18]

On 29 September 1945, Anglo-Dutch troops arrived in Jakarta to disarm and repatriate the Japanese garrison. They also planned on reasserting control over the colony.[19] On November 21, 1945, Suwiryo and his assistants were arrested by members of the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration.[16]

On 4 January 1946, Indonesian Republicans withdrew from Ally-occupied Jakarta and established the capital in Yogyakarta. War was not apparent in Jakarta and urban development continued in the city as the Dutch tried to re-establish themselves. In 1947, the Dutch succeeded in implementing a set of planning regulations for urban development—the SSO/SVV (Stadsvormings-ordonantie/Stadsvormings-verordening)—that had been devised prior to the war. Batavia was planned to expand with an addition of a new satellite city 8 kilometers south of the Koningsplein. This 730 ha area would become the Kebayoran satellite city, the first urban planning in Indonesia after the World War II.

On 27 December 1949, the Dutch recognised Indonesia as an independent country and sovereign federal state under the name of "Republic of the United States of Indonesia". At this time, the Jakarta City Administration was led by Mayor Sastro Mulyono.

Transition into a capital of an independent nation (1950s)

Expansion of city's boundary

After the recognition of Indonesian sovereignty on 27 December 1949, in March 1950, Jakarta was increased in size from 182 square kilometres to 530 square kilometres. Despite the dramatic increase in size, impact on the city's population was minimal: population of Jakarta was 1,340,625 in 1949 to 1,432,085 in 1950 to 1,661,125 in 1951. The new districts added to Jakarta at the time was sparsely populated and rural.[20]

Kebayoran Baru was still a satellite city of Jakarta and located outside the boundaries of Jakarta. The construction of thoroughfares such as Jalan Thamrin and Jalan Sudirman had been underway since 1949 and would only be opened in 1953.[20]

City development

Jakarta in the 1950s was more or less similar with the colonial period: banking districts were still centered in Kota around Kali Besar and Jalan Pintu Besar Utara. Chinese business hub were centered at Glodok, especially Pintu Kecil. The colonial Pasar Baru, Pasar Senen and Glodok were still the busiest markets in Jakarta. The European shopping and leisure districts were still centered at Harmoni Junction. Most colonial hotels retained their Dutch names, e.g. Hotel des Indes or Hotel Duta Indonesia, Hotel der Nederlanden or Hotel Dharma Nirmala, and Hotel des Galeries. Kemayoran airport handled both domestic and international flights.[21]

Jakarta's urban area in 1950 were enclosed within the city's railway network. Areas beyond the railway lines remained empty, e.g. Tomang and Grogol to the west, Pluit and swampy Ancol to the north. Areas to the east and northeast, e.g. the area between Jalan Gunung Sahari and Tanjung Priok remained rural (with the exception of the Kemayoran Airport). Kali Sunter (Sunter River) was in the countryside and would not be developed as residential area until the 1970s.[22]

Among new suburbs developed during the 1950s were Grogol, Tanah Tinggi, Bendungan Hilir and Pejompongan; mostly to provide housing for civic workers.

Despite the slow city development, the beginning of the 1950s saw construction of infrastructure that would lay a foundation for the explosive growth of Jakarta in the 1960s.[23] Jalan Thamrin and Jalan Sudirman were built between 1949 and 1953 to connect Central Jakarta with Kebayoran Baru.[21] These projects are usually collaboration between Dutch and Indonesia. The first buildings that were constructed along the Thamrin-Sudirman were Bank Indonesia headquarters (1958-1962), Hotel Indonesia (1959-1962), and the Welcome Monument.[21] AT that time, Jalan Sudirman was largely rural and devoid of any buildings until the 1970s, with the exception of Gelora Bung Karno sports complex.[21]

Taking over Dutch assets

After recognition of Indonesian sovereignty on 27 December 1949, transition from Dutch to Indonesian leadership occurred immediately as Dutch residences and properties were taken over by the Indonesian government.[24] Among the notable buildings conversion were:

- Governor-general's palace on Jalan Merdeka Utara became Istana Merdeka presidential palace.[24]

- The Concordia military social club building on Jalan Lapangan Banteng Timur became the national parliament until early 1965.[24]

- The Volksraad (People's Council) at Jalan Pejambon, that had earlier been the military commander's residence, became the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[24]

- The Binnenlands Bestuur administrative corps headquarters on Jalan Medan Merdeka Utara became the Ministry of Home Affairs.[24]

- The Ministry of Finance was moved to the grand Witte Huis on Jalan Lapangan Banteng Timur.[24]

- The Jakarta City Council chambers on Jalan Medan Merdeka Selatan remained the home of the Jakarta City Council, with the exception that the council was all Indonesian and under the leadership of an Indonesian mayor. The rank "mayor" would become governor in 1960.[24]

- The old STOVIA medical school became the faculty of medicine at the newly created University of Indonesia.[24]

- Colonial ANETA news agency on Jalan Antara was taken over by Indonesian owners and management between 1951 and 1955 as a forerunner of present government owned news agency, ANTARA.[24]

Despite the numerous departments converted into Indonesian control, from the economic perspective, the transition was much slower. The Dutch still owned key sectors of Indonesian economy during most of the 1950s, including banking, oil and shipping. Only in late 1957, the nationalization of Dutch assets would begin, partly triggered by the anger over the refusal of the Netherlands to transfer sovereignty of Irian Jaya to Indonesia. By 1960, almost all Dutch assets in Indonesia had been taken over and Dutch citizens were expelled from Indonesia.[25]

Expulsion of the Dutch and population boom

Expulsion of the Dutch caused tremendous social change in Jakarta. In the middle of 1952, 48,280 foreigners (excluding Chinese) were living in Jakarta, of which 90.2% were Dutch. By the end of 1950s, only a few hundred of the Dutch stayed in Jakarta. The 1960s was regarded as a decade when foreigners were no longer a common sight on the streets of Jakarta.[25]

The departure of the Dutch also caused a massive migration of the rural population into Jakarta, in response to a perception that the city was the place for economic opportunities. The kampung areas in Jakarta swelled as a result. There were house shortages, as well the lack of schools, medical services, water and electricity. In 1951 and 1952, 25 hectares of land was opened for housing at Grogol, 25 hectares at Tanah Tinggi (just south of Kemayoran Airport) and 25 hectares at Pejompongan. Another 15 hectares at Pejompongan were set for a water purification plant. The 730 hectare satellite city of Kebayoran Baru, which was conceived by the Dutch in the 1930s, remained the most important housing development in Jakarta in the 1950s.[26]

Infrastructure

Jakarta's tram system, which began in 1869 as horse-drawn trams, and would be developed up until the electric trams from 1899, would face competition with buses and faces financial issues. President Sukarno didn't believe trams was an effective system for Jakarta, and so gradually he began to stop the operation of the trams. By April 1960, tramlines only operated from Senen and Kramat to Jatinegara. By 1962, the tramway disappeared from Jakarta.[26]

The 1950s was known as the decade where the informal becak can be found extensively in Jakarta. Introduced to Jakarta in the 1930s, the number of becak soared in late 1940s, which occurred at the same time with the wave of immigration into Jakarta to find employment. 31,000 becaks were registered in 1953.

Proposal to relocate the capital

In the mid-1950s, driven by a sense of corruption and disproportionate government expenditure in Jakarta, there were proposals to relocate the capital. Those in support included Takdir Alisjahbana, who was unflattering in his depiction of the city. However, by 1957, these proposals were abandoned. Instead, the city's boundaries were expanded, and it became the Daerah Khusus Ibukota (DKI, Special Capital Territory), one of the provinces of Indonesia.[27]:201

Sukarno's nationalistic projects (1960-1965)

Monumental projects

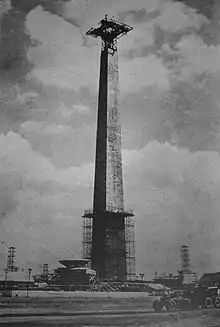

Dramatic changes in Jakarta's skyline occurred during the period between 1960-1965 when President Sukarno, also an architect and an urban planner, personally drove the city into a modern capital that would not only be the pride of the Indonesian nation, but would also be a "beacon" of a powerful new nation.[28] The short period would give Jakarta many of its most famous modernist landmarks and monuments.[15]

Sukarno had already transitioned the country to "Guided Democracy" between 1957 and 1959, which greatly increased his own political power. Sukarno's great power allowed him to award the 1962 Asian Games to Indonesia, with Jakarta as the host city. The event was used as a trigger to complete new landmarks in Jakarta, and so the first half of the 1960s saw large government-funded projects that were undertaken with openly nationalistic architecture.[23] By working on the optimistic monumental projects, Sukarno hoped to put the newly independent nation's pride on international display.[23]

Sukarno filled Jakarta with numbers of monuments. Numbers of monumental projects were conceived, planned and initiated during his administration. Some of the notable monumental projects of Sukarno during the first half of the 1960s were: Semanggi "clover-leaf" highway interchange, a broad avenue in Central Jakarta (Jalan M.H. Thamrin and Jalan Jenderal Sudirman), and Jalan Gatot Subroto; a broad by-pass connecting Tanjung Priok harbour with Halim Airport (Jalan Jenderal Ahmad Yani); four high-rise hotels, including Hotel Indonesia; a new parliament building; a stadium; Sarinah Department Store; the development of Ancol on the north coast of Jakarta to become Jakarta's main recreation complex; the largest mosque in Southeast Asia; and the widening of Jalan Thamrin and Jalan Sudirman ahead of the 1962 Asian Games.[29]

Most of Jakarta's monuments were initiated during the first half of the 1960s e.g. the National Monument, Selamat Datang Monument, Pemuda Monument at Senayan, Irian Jaya Liberation Monument at Lapangan Banteng, and the Dirgantara Monument at Pancoran.[29]

During the first half of the 1960s, government projects in Jakarta was so intense to the extent that Jakarta's citizens struggled to find cement and building materials for their own use.[29]

New suburbs

In early 1960s, increasing use of cars allow city development outside the constrain of railway network. Several suburbs began to be developed very far from the city center. Few of such developments were Grogol to the west, which was developed as a flood-proof residential area in the 1950s but was immediately flooded in February 1960; several housings to the west of Kemayoran Airport; and new housing developments on the west of Jalan Gajah Mada (Tanah Sereal, Krukut, Krendang and Duri) and on the east of Jalan Hayam Wuruk (Mangga Besar and Sawah Besar).[30] Several residential projects that were developed in the 1950s began to took shape in the 1960s, among them are Pejompongan (land opened in 1952), Bendungan Hilir, Setiabudi to the east of Jalan Sudirman, Tanah Tinggi (designated in 1951) and Rawa Sari (now Cempaka Putih Timur, designated in 1952).[31]

Fall of Sukarno

The period of monumental projects came to an immediate halt after the September 30 Movement in 1965. The incident would begin Sukarno's downfall from power. As a result, Jakarta's skyline was scarred with unfinished steel and concrete structures. A book Djakarta Through the Ages published in 1969 by the Jakarta City Government claimed: "Djakarta is dotted with steel skeletons and the concrete shells of unfinished buildings. There is no money to finish them. Who is able to finish and utilize these buildings?"[29] Among the delayed projects of Sukarno in Jakarta were Wisma Nusantara, a 30-storey office tower meant to be the tallest in Southeast Asia but was abandoned as an unfinished steel structure from 1966 to 1971; the Istiqlal Mosque, started in 1961 but not completed until 1978; the National Parliament building, started in 1965 and completed in stages up until 1983; the Hotel Borobudur which started in 1963 but to be opened in 1974; and the Balai Sarbini and Veteran's Building complex approved in 1965 but was opened in 1973.[32]

Rise of Ali Sadikin (1966 – late 1970s)

Improvement in infrastructure

In 1966, Ali Sadikin was elected as governor of Jakarta. He would serve as a governor of Jakarta from 1966–1977, Jakarta's longest-serving governor. Instead of focusing on monumental projects, Ali Sadikin focused his policy towards providing the basic needs of Jakarta's rapidly expanding population. Kampung improvement programs were one of his best-known projects. He repaired and build roads, provided public transport, better sanitation, health services and educational opportunities for the poor.[33]s

Among the roads that were constructed during the 1970s were Jalan Tomang Raya, which was built as a continuation of Jalan Kyai Caringin and which crossed over Jalan Letnan Jenderal S. Parman into Tanjung Duren and the new housing estate of Kebon Jeruk. At that time, the continuation of Jalan Tomang Raya was known as Jalan Arjuna, a relatively modest road which by the 1990s would be developed into the Jakarta-Tangerang-Merak toll road. Another road built in the 1970s was Jalan H R Rasuna Said. When completed, Rasuna Said, Sudirman, and Gatot Subroto formed the Golden Triangle of Jakarta, the where business, financial, and diplomatic heart of Jakarta. During this period, the first buildings appeared on Jalan Sudirman north of the Semanggi.[34]

Despite the success of the program, which won the Aga Khan Award for architecture in 1980, it was discontinued for its over-emphasis upon the improvement of only physical infrastructure.[33] Sadikin was also responsible for rehabilitating public services, banning rickshaws, and clearing out "slum dwellers" and "street peddlers".[35]

Completion of delayed projects

The 1970s saw the completion of projects that were begun in the 1960s by Sukarno.

The early 1970s saw Jalan Thamrin become a major thoroughfare with buildings higher than 5 storeys. Jalan Sudirman was still relatively empty, except for the Gelora Bung Karno sports complex and some housing at Bendungan Hilir and Setiabudi. Monuments such as the Irian Jaya Liberation Monument, the Prince Diponegoro Monument, the Heroes Monument, and the Dirgantara Monument were completed in the early 1970s.[36]

During the late 1970s, Ancol, another project proposed by Sukarno in the early 1960s, was already well-established as the Ancol Dreamland recreational area with its Bina Ria beach, a golf course, swimming pools, an oceanarium, Putri Duyung Cottage, Hotel Horison and its casinos, a drive-in theater, and new housing developments on both sides.[37]

Jakarta Fairs and other entertainments

In 1968, the Jakarta Fairs were initiated at Medan Merdeka, and the Taman Ismail Marzuki cultural center at Cikini was opened.[32] Taman Ria Remaja (Youth Recreation Park) was opened in the 1970s next to the Gelora Bung Karno.[34]

Decline of Kemayoran Airport

By 1974, a redeveloped Halim Perdanakusuma Airport became the international airport, with Kemayoran becoming a domestic-only airport. During the late 1970s, some housing west of Kemayoran Airport, such as the grid-like housing development of Pademangan, started to grow closer to the western edge of Kemayoran Airport.[37]

Economic growth (late 1970s – 1980s)

Early on during Ali Sadikin's years as governor, Suharto was elected president of Indonesia in 1967. He decided to promote foreign investment in Indonesia. Ali Sadikin ensured that Jakarta's infrastructure was able to support business opportunities and boost economic growth with the construction of the Jakarta Convention Center (1974) and several hotel projects. The 1970s saw a hotel building boom with the opening of nine major hotels: Hotel Kartika Plaza (1972), President Hotel (1973), Hotel Borobudur (1974), Hotel Ambassador/Aryaduta (1974), Hotel Sahid Jaya (1974), Hotel Kartika Chandra (1974), the Hilton Hotel (1976), Hotel Sari Pan Pacific (1976) and Mandarin Hotel (1978), as well as the extension of Hotel Indonesia in 1974.[32]

The 1970s also witnessed the redevelopment of Jakarta's two oldest markets: Pasar Senen and Pasar Tanah Abang. The Aldiron Plaza shopping center (now Blok M Square), considered to be the precursor of Jakarta's shopping malls, was opened in the mid-1970s.[32]

The situation in the 1970s encouraged the emergence of a large number of private housing projects, but government housing schemes were also implemented to cope with the growth of the urban population.

1980s–present

During the 1980s, smaller land sites were acquired for high-rise projects, while larger parcels of land were subdivided for low-key projects, such as the building of new shophouses. This period also saw the removal of kampongs from the inner-city areas and the destruction of many historical buildings.[33] One infamous case was the demolition of the Society of Harmonie and the subsequent construction of a parking lot.

The period between the late-1980s and the mid-1990s saw a massive increase in foreign investment as Jakarta became the focus of a real estate boom. The investment of overseas capital into joint-venture property and construction projects with local developers brought many foreign architects into Indonesia. However, unlike the Dutch architects of the 1930s, many of these expatriate architects were unfamiliar with the tropics, while their local partners had received similarly Modernist architectural training. As a result, downtown areas in Jakarta gradually resembled those of the large Western cities; and often at a high environmental cost: high-rise buildings consume huge amounts of energy in terms of air-conditioning and other services.[33]

The economic boom period of Jakarta ended abruptly in the 1997 Asian financial crisis and many projects were left abandoned. The city became a center of violence, protest, and political maneuvering, as long-time president, Suharto, began to lose his grip on power. Tensions reached a peak in May 1998, when four students were shot dead at Trisakti University by security forces; four days of riots ensued, resulting in damage to, or destruction of, an estimated 6,000 buildings, and the loss of 1,200 lives. The Chinese of the Glodok district were severely affected during the riot period and accounts of rape and murder later emerged.[35] In the following years, including several terms of ineffective Presidents, Jakarta was a center of popular protest and national political instability, including several Jemaah Islamiyah-connected bombings.

Since the turn of the century, the people of Jakarta have witnessed a period of political stability and prosperity, along with another construction boom.

See also

Notes and references

- "History of Jakarta". Jakarta.go.id. 8 March 2011. Archived from the original on June 8, 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- See also Perfected Spelling System as well as Wikipedia:WikiProject Indonesia/Naming conventions

- Lesson: Old Indonesian Spellings. StudyIndonesian. Retrieved on 2013-07-16.

- Sundakala: cuplikan sejarah Sunda berdasarkan naskah-naskah "Panitia Wangsakerta" Cirebon. Yayasan Pustaka Jaya, Jakarta. 2005.

- The Sunda Kingdom of West Java From Tarumanagara to Pakuan Pajajaran with the Royal Center of Bogor. Yayasan Cipta Loka Caraka. 2007.

- Dr. R. Soekmono (1988) [1973]. Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2, 2nd ed (5th reprint ed.). Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 60.

- Bujangga Manik Manuscript which is now located at the Bodleian Library of Oxford University in England, and travel records by Prince Bujangga Manik.(Three Old Sundanese Poems. KITLV Press. 2007.)

- "History of Jakarta". BeritaJakarta. Archived from the original on 2011-08-20.

- "History of Jakarta". BeritaJakarta.com. The Jakarta City Administration. 2002. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

- Liebenberg 2012, p. 209.

- Drakeley S. The History of Indonesia. Greenwood, 2005. ISBN 9780313331145

- de Vries J, van der Woude A. The First Modern Economy. Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500–1815. Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 9780521578257

- Ricklefs MC. A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1200. MacMillan, 2nd edition, 1991ISBN 0333576896

- "Batavia". De VOCsite (in Dutch). de VOCsite. 2002–2012. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 11.

- "Jakarta Dalam Angka – Jakarta in Figures – 2008". Jakarta Dalam Angka. Jakarta: BPS – Statistics DKI Jakarta Provincial Office: xlvii–xlix. 2008. ISSN 0215-2150.

- Waworoentoe 2013.

- Lapangan Merdeka / Monas. Merdeka Square page on official website of Jakarta. (in Indonesian)

- Jessup, John E. (1989). A Chronology of Conflict and Resolution, 1945-1985. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24308-5.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 15.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 37.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 13.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 97.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 35.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 36.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 39.

- Cribb R, Kahin A. Historical Dictionary of Indonesia. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 2nd edition ISBN 9780810849358

- Silver 2007, p. 101.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 99.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 17.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 19.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 101.

- Siregar 1998, pp. 130-1.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 27.

- Vaisutis, Justine; Martinkus, John; Batchelor, Dr. Trish (2007). Indonesia. Lonely Planet. p. 101. ISBN 9781741798456. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 21.

- Merrillees 2015, p. 25.

Further reading

- Blusse, Leonard. An Insane Administration and Insanitary Town: The Dutch East India Company and Batavia (1619–1799) (Springer Netherlands, 1985).

- de Jong, J.J.P. (1998). De waaier van het fortuin: van handelscompagnie tot koloniaal imperium : de Nederlanders in Azië en de Indonesische archipel. Sdu. ISBN 9789012086431.

- Liebenberg, Elri; Demhardt, Imre (2012). History of Cartography: International Symposium of the ICA Commission, 2010. Heidelberg: Springer. p. 209. ISBN 978-3-642-19087-2.

The United Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC in Dutch, literally "United East Indian Company")...

- Merrillees, Scott (2015). Jakarta: Portraits of a Capital 1950-1980. Jakarta: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 9786028397308.

- Ricklefs, Merle Calvin (1993), A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2194-7.

- Schoppert, Peter; Damais, Soedarmadji & Sosrowardoyo, Tara (1998), Java Style, Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 962-593-232-1.

- Silver, Christopher (2007). Planning the Megacity: Jakarta in the Twentieth Century - Planning, History and Environment Series. Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 9781135991227.

- Siregar, Sandi (1998). "The Architecture of Modern Indonesian Cities". In Tjahjono, Gunawan (ed.). Indonesian Heritage-Architecture. 6. Singapore: Archipelago Press. ISBN 981-3018-30-5.

- Witton, Patrick (2003), Indonesia, Melbourne: Lonely Planet, ISBN 1-74059-154-2.

External links

- Pictures and Map from 1733 (Homannische Erben, Nuernberg-Germany)