Afrasiyab (Samarkand)

Afrasiyab (Uzbek: Afrosiyob) is an ancient site of Northern Samarkand, present day Uzbekistan, that was occupied from c 500 BC to 1220 AD prior to the Mongol invasion in the 13th century.[1] The oldest layers date from the middle of the first millennium BC.[1] Today, it is a hilly grass mound located near the Bibi Khanaum Mosque. Excavations uncovered the now famous frescoes. Afrasiab Museum of Samarkand is located next to the archaeological site.

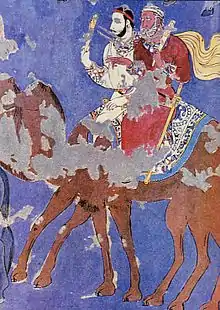

Details of a copy of one of the Afrasiab paintings at the Afrasiab Museum of Samarkand | |

Location of Afrasiyab in Uzbekistan  Afrasiyab (Samarkand) (Uzbekistan) | |

| Location | Uzbekistan |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | |

Overview

Afrasiyab is the oldest part and the ruined site of the ancient and medieval city of Samarkand. It was located on high ground for defensive reasons, south of a river valley and north of a large fertile area which has now become part of the city of Samarkand.

The habitation of the territories of Afrasiyab began in the 7th-6th century BC, as the centre of the Sogdian culture.[2]

The term Qal’a-ye Afrasiab (Castle of Afrasiab) appeared in written sources only towards the end of the 17th century. The name is popularly connected with the mythical King Afrasiab. Scholars consider Afrasiab to be a distortion and a corrupted form of the Tajik word Parsīāb (from Sogdian Paršvāb), meaning "beyond the black river", the river being Sīāhāb or Sīāb, which bounds the site to the north.[3] Afrā is the poetic form of the Persian word Farā (itself a poetic word), which means 'beyond, further', while Sīāb comes from sīāh meaning 'black' and Āb meaning 'water; river; sea' (depending on the context).

First archaeological excavations were carried out in Afrasiyab in the late 19th century, by Nikolay Veselovsky. In the 1920s, it was extensively excavated by the archaeologist Mikhail Evgenievich Masson who placed artifacts found at the site in the Samarkand museum.[4] His archaeological study revealed that a Samanid palace had once been located at Afrasiyab. It was again actively excavated during the 1960-70s.

The town

The area of Afrasiyab covers about 220 hectares, and the thickness of the archaeological strata reaches 8–12 metres. The town Afrasiyab had the form of an isosceles triangle, the base angle of which was looking to the south. Afrasiyab originated on the natural hill, that was intersected by numerous hollows, and the town itself was surrounded by high walls, which now look like a massive clay-built erection 40 meters high inside. The most long part of the town was 1.5 kilometers in width. The entrance to the town located in the middle part of the eastern wall. There were towers in Afrasiyab, the maximum length of which was 3,34 kilometers, and the remains of which was found on some places of the surrounding wall.[5]

Water to the town was generated in the water channels, earthenware pipes, and wells. So, it means that a lot of place was occupied by reservoirs, the biggest of which had a capacity of about a million gallons of water and was located near the southern wall.

No remains of traced streets were found, as the buildings around collapsed and ruined so narrow and crooked traces. Unbaked bricks on wooden framework, with clay molding were used to build the houses. Some of them had windows with gypsum lattices set with small pieces of glass.

There were found a lot of coins. On the base of them different dates of occupation of Afrasiyab was determined, which was mostly done by Viatkin. The found coins belonged to the Sasanids, some to the Bukhar-Khudats, and some to the Umaiyad and the Abbasid caliphs. In a large quantities the Samanid coins were found, the less common were coins of the Khwarazm Shahs, and the least frequent coins were Karakhanid's and Seljuk's ones. The coins of Mongke was the latest found coins. All of these found and researched coins show that Afrasiyab was inhabited from the fourth or fifth to the thirteenth century.[5]

Ruined buildings

In Afrasiyab were found five bathhouses, that were related to the 9th and 10th centuries. A bathhouse of Afrasiyab consisted of cisterns, baths, pipes supplying heat and water, dressing-rooms, massage chambers, warm and cold halls and open courtyards. Carved stucco and frescoes decorated some parts of a bathhouse.

In 1924 in Afrasiyab Viatkin made his research, at the place where a Buddhist fresco and a richly molded alabaster panel were found on the wall of an ancient room. There were found a clay-built, brick-covered, cupolaed edifice with well-preserved walls. Also there were found a lot of articles on the walls. On one of them On the wall of a small building nearby an Arabic inscription was found: "In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful, say: 'He is the God alone, God the eternal." The discoveries were dated by ninth- and tenth-century coins.

In I929, the remains of a house, which was related to the twelfth century, and a large shallow pit containing burnt wheat were found. They were found between the valley near the Siab irrigation canal and the ruins of the mosque. The ruins of dwellings were found on the three levels, and the lowest of them refers to the first centuries of our era, while the latest belongs the Samanid period, which also can be proved by coins that were found and related to the Samanids of the tenth century.

One of the wealthy medieval dwellings of Afrasiyab is the remains of a house that is referred to the tenth century. This house had a domed hall luxuriously panelled with carved gypsum stucco, which covered both inside and outside parts of the walls. In a present time this ornamentation presents an example of medieval art.

During the 1930s excavations by Viatkins there was found at the ruins of a palace complex with traces of splendid frescoes related to the Karakhanid period (from eleventh to twelfth centuries A.D.), which was located in the shahristan area. But the palace was destroyed during uprising against the Khworezmi power in 1212, and was later rebuilt.

To the west of Afrasiyab there were excavated a principal mosque and a minaret. The minaret was faced with bricks stamped with the Persian word Ikhshid, the title of the ancient Samarkand rulers. And the mosque was reconstructed several times as it was found. During Samanid era in the 10th century the mosque had a square form, sides of which were 78 by 78 meters. But during Karakhanid era in the eleventh-twelfth centuries it had a rectangular shape, expanding to 120 by 80 meters. In it there were found six doorways, the chains from the chandeliers which illuminated the columned hall and it was decorated with carved stucco, carved terracotta slabs and light-blue tiles.

_Citadel_Hellenistic.jpg.webp) Afrasiab Hellenistic citadel

Afrasiab Hellenistic citadel Ruins of Afrasiyab

Ruins of Afrasiyab

Murals

Remarkable murals show Varkhuman, the king of Samarkand, in the 7th century CE. He is seen being visited by embassies from numerous countries, including China.[7] There is also an inscription in the murals directly mentioning him.[7] His name is also known from Chinese histories.[7]

One of the murals show a Chinese Embassy carrying silk and a string of silkworm cocoons to the local Sogdian ruler.[7]

The scenes depicted in the Afrasiyab murals may have been painted in 648-651 CE, as the Western Turkic Khaganate was in its last days, and the Han Dynasty was increasing its territory in Central Asia.[8] Alternatively, it may have occurred soon after 658 CE, when the Tang Dynasty had conquered the Western Turkic Khaganate, and the king of Samarkand Varkhuman could directly enter into contacts with the Chinese.[9]

_Palace_Fresco_7th-8th_cent_Sogdian_Chamberlains_%2526_Interpreter_Introduce_Tibetan_Messengers.jpg.webp) Afrasiab Palace Fresco 7th-8th century. Sogdian Chamberlains & Interpreter Introduce Tibetan Messengers

Afrasiab Palace Fresco 7th-8th century. Sogdian Chamberlains & Interpreter Introduce Tibetan Messengers_and_Turkish_delegates_(right)_on_the_murals_of_Afrasiab%252C_Samarkand.jpg.webp) Afrasyab Chinese Embassy (left), carrying silk and a string of silkworm cocoons, and Turkish delegates (right), recognizable by their long plaits.[10]

Afrasyab Chinese Embassy (left), carrying silk and a string of silkworm cocoons, and Turkish delegates (right), recognizable by their long plaits.[10]_Palace_Fresco_7th-8th_cent_Sogdian_Varkhuman_King_of_Samarkand.jpg.webp) Afrasiab Palace Fresco 7th-8th century. Sogdian King of Samarkand Varkhuman

Afrasiab Palace Fresco 7th-8th century. Sogdian King of Samarkand Varkhuman Wall painting at the Ambassador’s Hall in Afrosiab

Wall painting at the Ambassador’s Hall in Afrosiab

Crafts

The most used pottery in Afrasiyab was glazed pottery, which included the most common forms like plates and dishes, pitchers.

But there were also found different types of pottery. The biggest part was the unglazed pottery, which was wheel-made, well fired, and simply ornamented in harmony with its purpose, which shows the master's skills. It included large vessels, several kinds of pitchers, jugs, saucers, and bowls.

The less perfect and inferior pottery was also found, which is the second type. The surfaces of the handmade pitchers and pots were carefully polished and covered with markings in the form of parallel lines, diamonds, crisscrosses, and spirals. According to Vfatkin this pottery relates to the period of the Tripolje culture.

There also were found the numerous terra-cotta slabs and miniature altars, which were covered inside and outside with a beautiful stamped floral ornamentation. The altars bore pictures of birds, columns, and the Arabic inscription "praise to God".

Also there was produced glass, that was made into small, exquisitely fashioned flasks, phials, tumblers, mugs, wineglasses, goblets, spoons, jugs, carafes, and bottles.

There were found tombstones for which there were used large river flagstones up to a meter in length. Most of them referred to the twelfth, less to the thirteenth, and much less to the fourteenth century. Each tombstone bore an inscription engraved in Arabic and showed the name of the person buried and the year of burial; some of the stones were decorated with arabesques. On one stone there was no inscription, only the engraved profile of a head wearing a castellated crown, as appears on the coins of the Bukhar-Khudats. At the other end of the stone an elephant and a bird were engraved.[5]

See also Afrasiab painting for wall paintings discovered in the archeological site.

Cemetery in Afrasiyab

Cemetery in Afrasiyab

References

- Archaeological Research in Central Asia of the Muslim Period, World Archaeology Vol. 14, No. 3, Islamic Archaeology (Feb., 1983), pp. 393-405 (13 pages)

- Darmesteter J., "Hang-e Afrasiab", Études Iraniennes (1883): 225-27.

- Yarshater, E., "Afrasiab", Encyclopædia Iranica - digital library; accessed January 18, 2007.

- "Mikhail Evgenievich Masson - the founder of the archaeological school in Central Asia". UNESCO. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- archaeological investigations in Central Asia 192=17-1937 by Henry Field and Eugene Prostov

- Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- Whitfield, Susan (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. British Library. Serindia Publications, Inc. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- Whitfield, Susan (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. British Library. Serindia Publications, Inc. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- Whitfield, Susan (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. British Library. Serindia Publications, Inc. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- Grenet, Frantz (2004). "Maracanda/Samarkand, une métropole pré-mongole". Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 5/6: Fig. B.

External links

Media related to Afrasiyab (Samarkand) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Afrasiyab (Samarkand) at Wikimedia Commons

%252C_and_Chach_(modern_Tashkent)_to_king_Varkhuman_of_Samarkand._648-651_CE%252C_Afrasiyab%252C_Samarkand.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)