Khanate of Bukhara

The Khanate of Bukhara (or Khanate of Bukhoro) (Persian: خانات بخارا; Uzbek: Buxoro Xonligi) was an Uzbek[5] state from the second quarter of the 16th century to the late 18th century in Central Asia or Turkestan. Bukhara became the capital of the short-lived Shaybanid empire during the reign of Ubaydallah Khan (1533–1540). The khanate reached its greatest extent and influence under its penultimate Shaybanid ruler, the scholarly Abdullah Khan II (r. 1557–1598).

Khanate of Bukhara خانات بخارا | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1506–1785 | |||||||||||||||

War flag | |||||||||||||||

.png.webp) The Khanate of Bukhara (green), c. 1600. | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | 39°46′N 64°26′E | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Persian (official, court, literature)[1][2] Chagatai Turkic[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam (Sunni, Naqshbandi Sufism) | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Khan | |||||||||||||||

• 1506–1510 | Muhammad Shaybani | ||||||||||||||

• 1599–1605 | Baqi Muhammad Khan | ||||||||||||||

• 1747–1753 | Muhammed Rahim | ||||||||||||||

• 1758–1785 | Abu’l Ghazi Khan | ||||||||||||||

| Ataliq | |||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||||||

| 1506 | |||||||||||||||

• Establishment of Janid dynasty | 1599 | ||||||||||||||

• The khanate is conquered by Nader shah After Mohammad Hakim surrenders | 1745 | ||||||||||||||

• Manghit dynasty takes control after Nader shah dies and his empire breaks up | 1747 | ||||||||||||||

• Establishment of Emirate of Bukhara | 1785 | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1902 | 2,000,000 est.[4] | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Khanate was ruled by the Janid Dynasty (Astrakhanids or Toqay Timurids). They were the last Genghisid descendants to rule Bukhara. In 1740, it was conquered by Nadir Shah, the Shah of Iran. After his death in 1747, the khanate was controlled by the non-Genghisid descendants of the Uzbek emir Khudayar Bi, through the prime ministerial position of ataliq. In 1785, his descendant, Shahmurad, formalized the family's dynastic rule (Manghit dynasty), and the khanate became the Emirate of Bukhara.[6] The Manghits were non-Genghisid and took the Islamic title of Emir instead of Khan since their legitimacy was not based on descent from Genghis Khan.

Shaybanid Dynasty

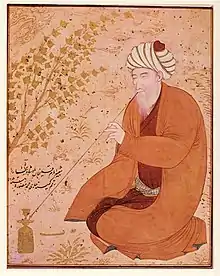

_(5719346105).jpg.webp)

The Shaybanid dynasty ruled the Khanate from 1506 to 1598. Under their rule, Bukhara became a center of arts and literature and educational reforms were introduced. In the sources of the second half of the 17th century, the expression “92 Uzbek tribes” is used in relation to the part of the population of Bukhara Khanate territory.[7]

Shaybani Khan was fond of poetry and wrote poetry in the Turkic language. A collection of his poems has come down to us. There are sources that Shaybani Khan wrote poetry in both Turkic and Persian. The "Divan" of Shaybani Khan's poems, written in the Central Asian Turkic literary language, is currently kept in the Topkapi manuscript collection in Istanbul. The manuscript of his philosophical and religious work: "Bahr ul-Khudo", written in the Central Asian Turkic literary language in 1508, is located in London.[8]

Shaybani Khan wrote poetry under the pseudonym "Shibani". He wrote a prose work called Risale-yi maarif-i Shaybani. It was written in the Turkic-Chagatai language in 1507 shortly after his capture of Khorasan and is dedicated to his son, Muhammad Timur-Sultan (the manuscript is kept in Istanbul). Ubaydulla Khan was a very educated person, he skillfully recited the Koran and provided it with comments in the Turkic language, was a gifted singer and musician. The formation of the most significant court literary circle in Maverannahr in the first half of the 16th century is associated with the name of Ubaydulla Khan. Ubaydulla Khan himself wrote poetry in Turkic, Persian and Arabic under the literary pseudonym Ubaydiy. A collection of his poems has reached us. [9]

In the Shaybanid era in the Bukhara Khanate, Agha-i Buzurg or "Great Lady" was a famous scholarly woman-Sufi (she died in 1522-23), she was also called "Mastura Khatun"[10]

Bukhara of the 16th century attracted skilled craftsmen of calligraphy and miniature-paintings, such as Sultan Ah Maskhadi, Mahmud ibn Eshaq Shakibi, the theoretician in calligraphy and dervish Mahmud Buklian, Molana Mahmud Muzahheb, and Jelaleddin Yusuf.

Abd al-Aziz Khan (1540–1550) established a library "having no equal" the world over. The prominent scholar Sultan Mirak Munshi worked there from 1540. The gifted calligrapher Mir Abid Khusaini produced masterpieces of Nastaliq and Reihani script. He was a brilliant miniature-painter, master of encrustation, and was the librarian (kitabdar) of Bukhara's library.[11]

The Shaybanids instituted a number of measures to improve the khanate's system of public education. Each neighborhood mahalla — unit of local self-government — of Bukhara had a hedge school, while prosperous families provided home education to their children. Children started elementary education at the age of six. After two years they could be taken to madrasah. The course of education in madrasah consisted of three steps of seven years each. Hence, the whole course of education in madrasah lasted twenty-one years. The pupils studied theology, arithmetic, jurisprudence, logic, music, and poetry. This educational system had a positive influence upon the development and wide circulation of the Persian and Uzbek languages, and on the development of literature, science, art, and skills.

Janid Dynasty

The Janid Dynasty (descendants of Astrakhanids) ruled the Khanate from 1599 until 1747. Yar Muhammad and his family had escaped from Astrakhan after Astrakhan fell to Russians. He had a son named Jani Muhammad who had two sons named Baqi Muhammad and Vali Muhammad Khan from his wife, who was the daughter of the last Shaybanid ruler.[12]

The son of Din Muhammad Sultan - Boqi Muhammad Khan in 1599 defeated Pir Muhammad Khan II, who had lost his authority. He became the real founder of a new dynasty of Janids or Ashtarkhanids in the Bukhara Khanate (1599-1756). Boqi Muhammad Khan, despite his short reign, carried out administrative, tax and military reforms in the country, which contributed to its further development. He issued coins with the inscription Baqi Muhammad Bahodirkhon and the names of the first four caliphs.[13]

The Bukhara Khanate received the highest development during the reign of Imamkuli-Khan (1611-1642).

During the reign of the Tokay Timurids in Samarkand and Bukhara, masterpieces of world architecture were built: the Registan architectural ensemble in Samarkand and the Labi havuz architectural ensemble in Bukhara.

During this period, the Uzbek poet Turdy wrote critical poems and called for the unity of 92 tribal Uzbek people. The most famous Uzbek poet is Mashrab, who composed a number of poems that are still popular today. In the 17th and early 18th centuries, historical works were written in Persian. Among the famous historians, Abdurahman Tole, Muhammad Amin Bukhari, Mutribi should be noted. [14]

List of rulers

- See Shaybanids.

- See Janids.

- Khanate of Bukhara breaks up into:

- See Manghits — (Emirate of Bukhara).

- See Yadigarids and later Qongirats — (Khanate of Khiva).

- See Mings — (Khanate of Kokand).

Janids

- Boqi Muhammad Khan (1599–1605)

- Vali Muhammad Khan (1605–1611)

- Imamkuli-Khan (1611–1642)

- Nadir Muhammad Khan (1642–1645)

- Abdul Aziz Khan (1645–1680)

- Subhan Quli Khan (1680–1702)[15][16][17]

- Ubaidullah Khan (1702–1711)

- Abu al-Fayz Khan (1711–1747)

- Muhammad Abd al-Mumin (1747–1748)

- Muhammad Ubaidullah II (1748–1753, nominal)

- Muhammad Rahim (usurper), atalik (1753–1756), khan (1756–1758)

- Shir Ghazi (1758–?)

- Abu'l Ghazi Khan (1758–1785)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khanate of Bukhara. |

- Emirate of Bukhara

- Russian conquest of Central Asia

- List of Turkic dynasties and countries

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- Uzbek Khanate

References

- Ulugbek Azizov (2015). Freeing from the "Territorial Trap". LIT Verlag Münster. p. 58. ISBN 9783643906243. Retrieved 2017-07-22.

The Bukhara Khanate as a new administrative entity was founded in 1533 and was the continuation of the Shaybanid dynas- ty. The khanate occupied the territory from Kashgar (west of Chi- na) to the Aral Sea, from Turkestan to the east part of Chorasan. The official language was Persian as well as Uzbek was spoken widely.

- Ira Marvin Lapidus - 2002, A history of Islamic societies, p.374

- Grenoble, Lenore (2003). Language Policy of the Soviet Union. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 1-4020-1298-5.

- Vegetation Degradation in Central Asia Under the Impact of Human Activities, Nikolaĭ Gavrilovich Kharin, page 49, 2002

- Peter B.Golden (2011) Central Asia in World History, p.115

- Soucek, Svat. A History of Inner Asia (2000), p. 180.

- Malikov A. “92 Uzbek tribes” in official discources and the oral traditions from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries in Golden Horde Review. 2020, volume 8 issue 3, p.520

- A.J.E.Bodrogligeti, «Muhammad Shaybani’s Bahru’l-huda : An Early Sixteenth Century Didactic Qasida in Chagatay», Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher, vol.54 (1982), p. 1 and n.4

- B. V. Norik, Rol' shibanidskikh praviteley v literaturnoy zhizni Maverannakhra XVI v. // Rakhmat-name. Spb, 2008, p.230

- Aminova Gulnora, Removing the Veil of Taqiyya: Dimensions of the Biography of Agha-yi Buzurg (a sixteenth-century female saint from Transoxiana). Ph.D. thesis, Harvard university, 2009

- Khasan Nisari. Muzahir al-Ahbab

- McChesney, R. D. "The reforms" of Baqi Muhammad Khan in Central Asiatic Journal 24, no. 1/2 (1980): 78.

- Davidovich Ye. A., Istoriya monetnogo dela Sredney Azii XVII—XVIII vv. Dushanbe, 1964.

- https://iranicaonline.org/articles/central-asia-vi

- László Karoly (14 November 2014). A Turkic Medical Treatise from Islamic Central Asia: A Critical Edition of a Seventeenth-Century Chagatay Work by Subḥān Qulï Khan. BRILL. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-90-04-28498-2.

- Orvostörténeti Közlemények: Communicationes de historia artis medicinae. Könyvtár. 2006. p. 52.

- Nil Sarı; International Society of the History of Medicine (2005). Otuz Sekizinci Uluslararası Tıp Tarihi Kongresi Bildiri Kitabı, 1-6 Eylül 2002. Türk Tarih Kurumu. p. 845. ISBN 9789751618252.

Further reading

- DeWeese, Devin (2009). "Bukhara Khanate". In Esposito, John L. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford University Press.