Human cannibalism

Human cannibalism is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh or internal organs of other human beings. A person who practices cannibalism is called a cannibal. The meaning of "cannibalism" has been extended into zoology to describe an individual of a species consuming all or part of another individual of the same species as food, including sexual cannibalism.

| Part of a series on |

| Homicide |

|---|

| Murder |

|

Note: Varies by jurisdiction

|

| Manslaughter |

| Non-criminal homicide |

|

Note: Varies by jurisdiction |

| By victim or victims |

| Family |

| Other |

The Island Carib people of the Lesser Antilles, from whom the word "cannibalism" is derived, acquired a long-standing reputation as cannibals after their legends were recorded in the 17th century.[1] Some controversy exists over the accuracy of these legends and the prevalence of actual cannibalism in the culture. Cannibalism was practised in New Guinea and in parts of the Solomon Islands, and flesh markets existed in some parts of Melanesia.[2] Fiji was once known as the "Cannibal Isles".[3] Cannibalism has been well documented in much of the world, including Fiji, the Amazon Basin, the Congo, and the Māori people of New Zealand.[4] Neanderthals are believed to have practised cannibalism,[5][6] and Neanderthals may have been eaten by anatomically modern humans.[7] Cannibalism was also practised in ancient Egypt, Roman Egypt and during famines in Egypt such as the great famine of 1199–1202.[8][9]

Cannibalism has recently been both practised and fiercely condemned in several wars, especially in Liberia[10] and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[11] It was still practised in Papua New Guinea as of 2012, for cultural reasons[12][13] and in ritual and in war in various Melanesian tribes. Cannibalism has been said to test the bounds of cultural relativism because it challenges anthropologists "to define what is or is not beyond the pale of acceptable human behavior".[1] Some scholars argue that no firm evidence exists that cannibalism has ever been a socially acceptable practice anywhere in the world, at any time in history, although this has been consistently debated against.[14]

A form of cannibalism popular in early modern Europe was the consumption of body parts or blood for medical purposes. This practice was at its height during the 17th century, although as late as the second half of the 19th century some peasants attending an execution are recorded to have "rushed forward and scraped the ground with their hands that they might collect some of the bloody earth, which they subsequently crammed in their mouth, in hope that they might thus get rid of their disease."[15]

Cannibalism has occasionally been practiced as a last resort by people suffering from famine, even in modern times. Famous examples include the ill-fated Donner Party (1846–47) and, more recently, the crash of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 (1972), after which some survivors ate the bodies of the dead. Additionally, there are cases of people suffering from mental illness engaging in cannibalism for sexual pleasure, such as Jeffrey Dahmer and Albert Fish. There is resistance to formally labeling cannibalism a mental disorder.[16]

Etymology

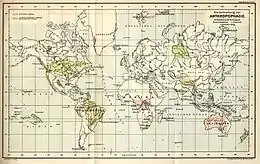

The word "cannibalism" is derived from Caníbales, the Spanish name for the Caribs,[17] a West Indies tribe that may have practiced cannibalism,[18] from Spanish canibal or caribal, "a savage". The term anthropophagy, meaning "eating humans", is also used for human cannibalism.

Reasons

In some societies, cannibalism is a cultural norm. Consumption of a person from within the same community is called endocannibalism; ritual cannibalism of the recently deceased can be part of the grieving process[19] or be seen as a way of guiding the souls of the dead into the bodies of living descendants.[20] Exocannibalism is the consumption of a person from outside the community, usually as a celebration of victory against a rival tribe.[20] Both types of cannibalism can also be fueled by the belief that eating a person's flesh or internal organs will endow the cannibal with some of the characteristics of the deceased.[21]

In most parts of the world, cannibalism is not a societal norm, but is sometimes resorted to in situations of extreme necessity. The survivors of the shipwrecks of the Essex and Méduse in the 19th century are said to have engaged in cannibalism, as did the members of Franklin's lost expedition and the Donner Party. Such cases generally involve necro-cannibalism (eating the corpse of someone who is already dead) as opposed to homicidal cannibalism (killing someone for food). In English law, the latter is always considered a crime, even in the most trying circumstances. The case of R v Dudley and Stephens, in which two men were found guilty of murder for killing and eating a cabin boy while adrift at sea in a lifeboat, set the precedent that necessity is no defence to a charge of murder.

In pre-modern medicine, the explanation given by the now-discredited theory of humorism for cannibalism was that it came about within a black acrimonious humor, which, being lodged in the linings of the ventricle, produced the voracity for human flesh.[22]

Medical aspects

A well-known case of mortuary cannibalism is that of the Fore tribe in New Guinea, which resulted in the spread of the prion disease kuru.[23] Although the Fore's mortuary cannibalism was well documented, the practice had ceased before the cause of the disease was recognized. However, some scholars argue that although post-mortem dismemberment was the practice during funeral rites, cannibalism was not. Marvin Harris theorizes that it happened during a famine period coincident with the arrival of Europeans and was rationalized as a religious rite.

In 2003, a publication in Science received a large amount of press attention when it suggested that early humans may have practiced extensive cannibalism.[24][25] According to this research, genetic markers commonly found in modern humans worldwide suggest that today many people carry a gene that evolved as protection against the brain diseases that can be spread by consuming human brain tissue.[26] A 2006 reanalysis of the data questioned this hypothesis,[27] because it claimed to have found a data collection bias, which led to an erroneous conclusion.[28] This claimed bias came from incidents of cannibalism used in the analysis not being due to local cultures, but having been carried out by explorers, stranded seafarers or escaped convicts.[29] The original authors published a subsequent paper in 2008 defending their conclusions.[30]

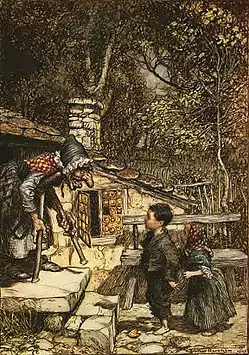

Myths, legends and folklore

.jpg.webp)

Cannibalism features in the folklore and legends of many cultures and is most often attributed to evil characters or as extreme retribution for some wrongdoing. Examples include the witch in "Hansel and Gretel", Lamia of Greek mythology and Baba Yaga of Slavic folklore.

A number of stories in Greek mythology involve cannibalism, in particular cannibalism of close family members, e.g., the stories of Thyestes, Tereus and especially Cronus, who was Saturn in the Roman pantheon. The story of Tantalus also parallels this.

The wendigo is a creature appearing in the legends of the Algonquian people. It is thought of variously as a malevolent cannibalistic spirit that could possess humans or a monster that humans could physically transform into. Those who indulged in cannibalism were at particular risk,[31] and the legend appears to have reinforced this practice as taboo. The Zuni people tell the story of the Átahsaia – a giant who cannibalizes his fellow demons and seeks out human flesh.

The wechuge is a demonic cannibalistic creature that seeks out human flesh. It is a creature appearing in the Native American mythology of the Athabaskan people.[32] It is said to be half monster and half human-like; however, it has many shapes and forms.

Accusations

William Arens, author of The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy,[33] questions the credibility of reports of cannibalism and argues that the description by one group of people of another people as cannibals is a consistent and demonstrable ideological and rhetorical device to establish perceived cultural superiority. Arens bases his thesis on a detailed analysis of numerous "classic" cases of cultural cannibalism cited by explorers, missionaries, and anthropologists. He asserts that many were steeped in racism, unsubstantiated, or based on second-hand or hearsay evidence.

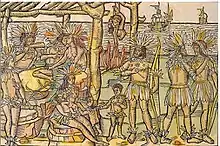

Accusations of cannibalism helped characterize indigenous peoples as "uncivilized", "primitive", or even "inhuman."[34] These assertions promoted the use of military force as a means of "civilizing" and "pacifying" the "savages". During the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire and its earlier conquests in the Caribbean there were widespread reports of cannibalism, justifying the conquest. Cannibals were exempt from Queen Isabella's prohibition on enslaving the indigenous.[35] Another example of the sensationalism of cannibalism and its connection to imperialism occurred during Japan's 1874 expedition to Taiwan. As Eskildsen describes, there was an exaggeration of cannibalism by Taiwanese indigenous peoples in Japan's popular media such as newspapers and illustrations at the time.[36]

This Horrid Practice: The Myth and Reality of Traditional Maori Cannibalism (2008) by New Zealand historian Paul Moon received a hostile reception by many Maori, who felt the book tarnished their whole people.[37] [38] The title of the book is drawn from the 16 January 1770 journal entry of Captain James Cook, who, in describing acts of Māori cannibalism, stated "though stronger evidence of this horrid practice prevailing among the inhabitants of this coast will scarcely be required, we have still stronger to give."[39]

History

Among modern humans, cannibalism has been practiced by various groups.[26] It was practiced by humans in Prehistoric Europe,[40][41] Mesoamerica,[42] South America,[43] among Iroquoian peoples in North America,[44] Māori in New Zealand,[45] the Solomon Islands,[46] parts of West Africa[18] and Central Africa,[18] some of the islands of Polynesia,[18] New Guinea,[47] Sumatra,[18] and Fiji.[48] Evidence of cannibalism has been found in ruins associated with the Ancestral Puebloans of the Southwestern United States as well as (at Cowboy Wash in Colorado).[49][50][51]

Pre-history

There is evidence, both archaeological and genetic, that cannibalism has been practiced for hundreds of thousands of years by early Homo Sapiens and archaic hominins.[52] Human bones that have been "de-fleshed" by other humans go back 600,000 years. The oldest Homo sapiens bones (from Ethiopia) show signs of this as well.[52] Some anthropologists, such as Tim D. White, suggest that ritual cannibalism was common in human societies prior to the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic period. This theory is based on the large amount of "butchered human" bones found in Neanderthal and other Lower/Middle Paleolithic sites.[53] Cannibalism in the Lower and Middle Paleolithic may have occurred because of food shortages.[54] It has been also suggested that removing dead bodies through ritual cannibalism might have been a means of predator control, aiming to eliminate predators' and scavengers' access to hominid (and early human) bodies.[55] Jim Corbett proposed that after major epidemics, when human corpses are easily accessible to predators, there are more cases of man-eating leopards,[56] so removing dead bodies through ritual cannibalism (before the cultural traditions of burying and burning bodies appeared in human history) might have had practical reasons for hominids and early humans to control predation.

In Gough's Cave, England, remains of human bones and skulls, around 14,700 years old, suggest that cannibalism took place amongst the people living in or visiting the cave,[57] and that they may have used human skulls as drinking vessels.[58][59][60]

Researchers have found physical evidence of cannibalism in ancient times. In 2001, archaeologists at the University of Bristol found evidence of Iron Age cannibalism in Gloucestershire.[61] Cannibalism was practiced as recently as 2000 years ago in Great Britain.[62]

Early history

Cannibalism is mentioned many times in early history and literature. Herodotus in "The Histories" (450s to the 420s BCE[63]) claimed, that after eleven days' voyage up the Borysthenes (Dnieper in Europe) a desolated land extended for a long way, and later the country of the man-eaters (other than Scythians) was located, and beyond it again a desolated area extended where no men lived.[64]

The tomb of ancient Egyptian king Unas contained a hymn in praise to the king portraying him as a cannibal.[65]

The Stoic philosopher Chrysippus wrote in his treatise On Justice that cannibalism was ethically acceptable.[66]

Polybius records that Hannibal Monomachus once suggested to Hannibal Barca that he teach his army to adopt cannibalism in order to be properly supplied in his travel to Italy, although Barca and his officers could not bring themselves to practice it. In the same war, Gaius Terentius Varro once claimed to the citizens of Capua that Barca's Gaul and Spanish mercenaries fed on human flesh, though this claim seemed to be acknowledged as false.[67]

Cassius Dio recorded cannibalism practiced by the bucoli, Egyptian tribes led by Isidorus against Rome. They sacrificed and devoured two Roman officers in ritualistic fashion, swearing an oath over their entrails.[68]

According to Appian, during the Roman Siege of Numantia in the second century BCE, the population of Numantia was reduced to cannibalism and suicide.[69]

Cannibalism was reported by Josephus during the siege of Jerusalem by Rome in 70 CE.[70]

Jerome, in his letter Against Jovinianus, discusses how people come to their present condition as a result of their heritage, and he then lists several examples of peoples and their customs. In the list, he mentions that he has heard that Attacotti eat human flesh and that Massagetae and Derbices (a people on the borders of India) kill and eat old people.[71]

Reports of cannibalism were recorded during the First Crusade, as Crusaders were alleged to have fed on the bodies of their dead opponents following the Siege of Ma'arra. Amin Maalouf also alleges further cannibalism incidents on the march to Jerusalem, and to the efforts made to delete mention of these from Western history.[72] During Europe's Great Famine of 1315–17, there were many reports of cannibalism among the starving populations. In North Africa, as in Europe, there are references to cannibalism as a last resort in times of famine.[73]

The Moroccan Muslim explorer ibn Battuta reported that one African king advised him that nearby people were cannibals (although this may have been a prank played on ibn Battuta by the king to fluster his guest). Ibn Batutta reported that Arabs and Christians were safe, as their flesh was "unripe" and would cause the eater to fall ill.[74]

For a brief time in Europe, an unusual form of cannibalism occurred when thousands of Egyptian mummies preserved in bitumen were ground up and sold as medicine.[75] The practice developed into a wide-scale business which flourished until the late 16th century. This "fad" ended because the mummies were revealed actually to be recently killed slaves. Two centuries ago, mummies were still believed to have medicinal properties against bleeding, and were sold as pharmaceuticals in powdered form (see human mummy confection and mummia).[76]

In China during the Tang dynasty, cannibalism was supposedly resorted to by rebel forces early in the period (who were said to raid neighboring areas for victims to eat), as well as both soldiers and civilians besieged during the rebellion of An Lushan. Eating an enemy's heart and liver was also claimed to be a feature of both official punishments and private vengeance.[77] References to cannibalizing the enemy have also been seen in poetry written in the Song dynasty (for example, in Man Jiang Hong), although the cannibalizing is perhaps poetic symbolism, expressing hatred towards the enemy.

Charges of cannibalism were levied against the Qizilbash of the Safavid Ismail.[78]

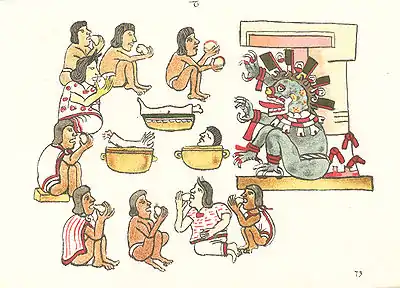

There is universal agreement that some Mesoamerican people practiced human sacrifice, but there is a lack of scholarly consensus as to whether cannibalism in pre-Columbian America was widespread. At one extreme, anthropologist Marvin Harris, author of Cannibals and Kings, has suggested that the flesh of the victims was a part of an aristocratic diet as a reward, since the Aztec diet was lacking in proteins. While most historians of the pre-Columbian era believe that there was ritual cannibalism related to human sacrifices, they do not support Harris's thesis that human flesh was ever a significant portion of the Aztec diet.[79][80][81] Others have hypothesized that cannibalism was part of a blood revenge in war.[82]

Early modern and colonial era

European explorers and colonizers brought home many stories of cannibalism practiced by the native peoples they encountered, but there is now archeological and written evidence for English settlers' cannibalism in 1609 in the Jamestown Colony under famine conditions.[83]

In Spain's overseas expansion to the New World, the practice of cannibalism was reported by Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean islands, and the Caribs were greatly feared because of their supposed practice of it. Queen Isabel of Castile had forbade the Spaniards to enslave the indigenous, but if they were "guilty" of cannibalism, they could be enslaved.[84] The accusation of cannibalism became a pretext for attacks on indigenous groups and justification for the Spanish conquest.[85] In Yucatán, shipwrecked Spaniard Jerónimo de Aguilar, who later became a translator for Hernán Cortés, reported to have witnessed fellow Spaniards sacrificed and eaten, but escaped from captivity where he was being fattened for sacrifice himself.[86] In the Florentine Codex (1576) compiled by Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún from information provided by indigenous eyewitnesses has questionable evidence of Mexica (Aztec) cannibalism. Franciscan friar Diego de Landa reported on Yucatán instances.[87]

In early Brazil, there is reportage of cannibalism among the Tupinamba.[88] It is recorded about the natives of the captaincy of Sergipe in Brazil: "They eat human flesh when they can get it, and if a woman miscarries devour the abortive immediately. If she goes her time out, she herself cuts the navel-string with a shell, which she boils along with the secondine [i.e. placenta], and eats them both."[89] (see human placentophagy). In modern Brazil, a black comedy film, How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman, mostly in the Tupi language, portrays a Frenchman captured by the indigenous and his demise.

The 1913 Handbook of Indians of Canada (reprinting 1907 material from the Bureau of American Ethnology), claims that North American natives practicing cannibalism included "... the Montagnais, and some of the tribes of Maine; the Algonkin, Armouchiquois, Iroquois, and Micmac; farther west the Assiniboine, Cree, Foxes, Chippewa, Miami, Ottawa, Kickapoo, Illinois, Sioux, and Winnebago; in the south the people who built the mounds in Florida, and the Tonkawa, Attacapa, Karankawa, Caddo, and Comanche; in the northwest and west, portions of the continent, the Thlingchadinneh and other Athapascan tribes, the Tlingit, Heiltsuk, Kwakiutl, Tsimshian, Nootka, Siksika, some of the Californian tribes, and the Ute. There is also a tradition of the practice among the Hopi, and mentions of the custom among other tribes of New Mexico and Arizona. The Mohawk, and the Attacapa, Tonkawa, and other Texas tribes were known to their neighbours as 'man-eaters.'"[90] The forms of cannibalism described included both resorting to human flesh during famines and ritual cannibalism, the latter usually consisting of eating a small portion of an enemy warrior. From another source, according to Hans Egede, when the Inuit killed a woman accused of witchcraft, they ate a portion of her heart.[91]

As with most lurid tales of native cannibalism, these stories are treated with a great deal of scrutiny, as accusations of cannibalism were often used as justifications for the subjugation or destruction of "savages". However, there were several well-documented cultures that engaged in regular eating of the dead, such as New Zealand's Māori. The very first encounter between Europeans and Māori may have involved cannibalism of a Dutch sailor.[92] In June 1772, the French explorer Marion du Fresne and 26 members of his crew were killed and eaten in the Bay of Islands.[93] In an 1809 incident known as the Boyd massacre, about 66 passengers and crew of the Boyd were killed and eaten by Māori on the Whangaroa peninsula, Northland. Cannibalism was already a regular practice in Māori wars.[94] In another instance, on July 11, 1821, warriors from the Ngapuhi tribe killed 2,000 enemies and remained on the battlefield "eating the vanquished until they were driven off by the smell of decaying bodies".[95] Māori warriors fighting the New Zealand government in Titokowaru's War in New Zealand's North Island in 1868–69 revived ancient rites of cannibalism as part of the radical Hauhau movement of the Pai Marire religion.[96]

Other islands in the Pacific were home to cultures that allowed cannibalism to some degree. In parts of Melanesia, cannibalism was still practiced in the early 20th century, for a variety of reasons—including retaliation, to insult an enemy people, or to absorb the dead person's qualities.[97] One tribal chief, Ratu Udre Udre in Rakiraki, Fiji, is said to have consumed 872 people and to have made a pile of stones to record his achievement.[98][99] Fiji was nicknamed the "Cannibal Isles" by European sailors, who avoided disembarking there. The dense population of Marquesas Islands, Polynesia, was concentrated in the narrow valleys, and consisted of warring tribes, who sometimes practiced cannibalism on their enemies. Human flesh was called "long pig".[100][101] W. D. Rubinstein wrote:

It was considered a great triumph among the Marquesans to eat the body of a dead man. They treated their captives with great cruelty. They broke their legs to prevent them from attempting to escape before being eaten, but kept them alive so that they could brood over their impending fate. ... With this tribe, as with many others, the bodies of women were in great demand.[4]

This period of time was also rife with instances of explorers and seafarers resorting to cannibalism for survival.

- The survivors of the sinking of the French ship Méduse in 1816 resorted to cannibalism after four days adrift on a raft, and their plight was made famous by Théodore Géricault's painting Raft of the Medusa.

- After a whale sank the Essex of Nantucket on 20 November 1820 (an important source event for Herman Melville's Moby-Dick), the survivors, in three small boats, resorted, by common consent, to cannibalism in order for some to survive.[102]

- Sir John Franklin's lost polar expedition is another example of cannibalism out of desperation.[103]

- On land, the Donner Party found itself stranded by snow in the Donner Pass, a high mountain pass in California, without adequate supplies during the Mexican–American War, leading to several instances of cannibalism.[104]

- One notorious cannibal was mountain man Boone Helm, who was known as "The Kentucky Cannibal" for eating several of his fellow travelers, from 1850 until his eventual hanging in 1864.

- The case of R v. Dudley and Stephens (1884) 14 QBD 273 (QB) is an English case which dealt with four crew members of an English yacht, the Mignonette, who were cast away in a storm some 2,600 kilometres (1,600 mi) from the Cape of Good Hope. After several days, one of the crew, a seventeen-year-old cabin boy, fell unconscious due to a combination of the famine and drinking seawater. The others (one possibly objecting) decided then to kill him and eat him. They were picked up four days later. Two of the three survivors were found guilty of murder. A significant outcome of this case was that necessity in English criminal law was determined to be no defence against a charge of murder.[105]

Further examples

Roger Casement, writing to a consular colleague in Lisbon on August 3, 1903 from Lake Mantumba in the Congo Free State, said:

"The people round here are all cannibals. You never saw such a weird looking lot in your life. There are also dwarfs (called Batwas) in the forest who are even worse cannibals than the taller human environment. They eat man flesh raw! It's a fact." Casement then added how assailants would "bring down a dwarf on the way home, for the marital cooking pot ... The Dwarfs, as I say, dispense with cooking pots and eat and drink their human prey fresh cut on the battlefield while the blood is still warm and running. These are not fairy tales, my dear Cowper, but actual gruesome reality in the heart of this poor, benighted savage land."[106]

During the 1892–1894 war between the Congo Free State and the Swahili–Arab city-states of Nyangwe and Kasongo in Eastern Congo, there were reports of widespread cannibalization of the bodies of defeated Arab combatants by the Batetela allies of Belgian commander Francis Dhanis.[107] The Batetela, "like most of their neighbors were inveterate cannibals."[108] According to Dhanis's medical officer, Captain Hinde, their town of Ngandu had "at least 2,000 polished human skulls" as a "solid white pavement in front" of its gates, with human skulls crowning every post of the stockade.[108]

In April 1892, 10,000 of the Batetela, under the command of Gongo Lutete, joined forces with Dhanis in a campaign against the Swahili–Arab leaders Sefu and Mohara.[108] After one early skirmish in the campaign, Hinde "noticed that the bodies of both the killed and wounded had vanished." When fighting broke out again, Hinde saw his Batetela allies drop human arms, legs and heads on the road.[109] One young Belgian officer wrote home: "Happily Gongo's men ate them up [in a few hours]. It's horrible but exceedingly useful and hygienic ... I should have been horrified at the idea in Europe! But it seems quite natural to me here. Don't show this letter to anyone indiscreet."[110] After the massacre at Nyangwe, Lutete "hid himself in his quarters, appalled by the sight of thousands of men smoking human hands and human chops on their camp fires, enough to feed his army for many days."[108]

In West Africa, the Leopard Society was a cannibalistic secret society that existed until the mid-1900s. Centered in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Ivory Coast, the Leopard men would dress in leopard skins, and waylay travelers with sharp claw-like weapons in the form of leopards' claws and teeth.[111] The victims' flesh would be cut from their bodies and distributed to members of the society.[112]

Modern era

Further instances include cannibalism as ritual practice; cannibalism in times of drought, famine and other destitution; as well as cannibalism as criminal acts and war crimes throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

World War II

Many instances of cannibalism by necessity were recorded during World War II. For example, during the 872-day Siege of Leningrad, reports of cannibalism began to appear in the winter of 1941–1942, after all birds, rats, and pets were eaten by survivors. Leningrad police even formed a special division to combat cannibalism.[113][114]

Some 2.8 million Soviet POWs died in Nazi custody in less than eight months during 1941–42.[115] According to the USHMM, by the winter of 1941, "starvation and disease resulted in mass death of unimaginable proportions".[116] This deliberate starvation led to many incidents of cannibalism.[117]

Following the Soviet victory at Stalingrad it was found that some German soldiers in the besieged city, cut off from supplies, resorted to cannibalism.[118] Later, following the German surrender in January 1943, roughly 100,000 German soldiers were taken prisoner of war (POW). Almost all of them were sent to POW camps in Siberia or Central Asia where, due to being chronically underfed by their Soviet captors, many resorted to cannibalism. Fewer than 5,000 of the prisoners taken at Stalingrad survived captivity.[119]

Cannibalism took place in the concentration and death camps in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), a Nazi German puppet state which was governed by the fascist Ustasha organization, who committed the Genocide of Serbs and the Holocaust in NDH.[120][121][122][123] Some survivors testified that some of the Ustashas drank the blood from the slashed throats of the victims.[121][124]

Japanese

The Australian War Crimes Section of the Tokyo tribunal, led by prosecutor William Webb (the future Judge-in-Chief), collected numerous written reports and testimonies that documented Japanese soldiers' acts of cannibalism among their own troops, on enemy dead, as well as on Allied prisoners of war in many parts of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. In September 1942, Japanese daily rations on New Guinea consisted of 800 grams of rice and tinned meat. However, by December, this had fallen to 50 grams.[125]:78–80 According to historian Yuki Tanaka, "cannibalism was often a systematic activity conducted by whole squads and under the command of officers".[126]

In some cases, flesh was cut from living people. A prisoner of war from the British Indian Army, Lance Naik Hatam Ali, testified that in New Guinea: "the Japanese started selecting prisoners and every day one prisoner was taken out and killed and eaten by the soldiers. I personally saw this happen and about 100 prisoners were eaten at this place by the Japanese. The remainder of us were taken to another spot 80 kilometres (50 miles) away where 10 prisoners died of sickness. At this place, the Japanese again started selecting prisoners to eat. Those selected were taken to a hut where their flesh was cut from their bodies while they were alive and they were thrown into a ditch where they later died."[127]

Another well-documented case occurred in Chichi-jima in February 1945, when Japanese soldiers killed and consumed five American airmen. This case was investigated in 1947 in a war crimes trial, and of 30 Japanese soldiers prosecuted, five (Maj. Matoba, Gen. Tachibana, Adm. Mori, Capt. Yoshii, and Dr. Teraki) were found guilty and hanged.[128] In his book Flyboys: A True Story of Courage, James Bradley details several instances of cannibalism of World War II Allied prisoners by their Japanese captors.[129] The author claims that this included not only ritual cannibalization of the livers of freshly killed prisoners, but also the cannibalization-for-sustenance of living prisoners over the course of several days, amputating limbs only as needed to keep the meat fresh.[130]

There are more than 100 documented cases in Australia's government archives of Japanese soldiers practising cannibalism on enemy soldiers and civilians in New Guinea during the war.[131][132] For instance, from an archived case, an Australian lieutenant describes how he discovered a scene with cannibalized bodies, including one "consisting only of a head which had been scalped and a spinal column" and that "[i]n all cases, the condition of the remains were such that there can be no doubt that the bodies had been dismembered and portions of the flesh cooked".[131][132] In another archived case, a Pakistan corporal (who was captured in Singapore and transported to New Guinea by the Japanese) testified that Japanese soldiers cannibalized a prisoner (some were still alive) per day for about 100 days.[131][132] There was also an archived memo, in which a Japanese general stated that eating anyone except enemy soldiers was punishable by death.[132] Toshiyuki Tanaka, a Japanese scholar in Australia, mentions that it was done "to consolidate the group feeling of the troops" rather than due to food shortage in many of the cases.[131] Tanaka also states that the Japanese committed the cannibalism under supervision of their senior officers and to serve as a power projection tool.[133]

Jemadar Abdul Latif (VCO of the 4/9 Jat Regiment of the British Indian Army and POW rescued by the Australians at Sepik Bay in 1945) stated that the Japanese soldiers ate both Indian POWs and local New Guinean people.[133] At the camp for Indian POWs in Wewak, where many died and 19 POWs were eaten, the Japanese doctor and lieutenant Tumisa would send an Indian out of the camp after which a Japanese party would kill and eat flesh from the body as well as cut off and cook certain body parts (liver, buttock muscles, thighs, legs, and arms), according to Captain R. U. Pirzai in a The Courier-Mail report of 25 August 1945.[133]

Africa

Cannibalism has been reported in several recent African conflicts, including the Second Congo War,[134] and the civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Democratic Republic of Congo

A UN human rights expert reported in July 2007 that sexual atrocities against Congolese women go "far beyond rape" and include sexual slavery, forced incest, fistula mutilation of genitals with sharp objects, and cannibalism.[134][135] This may be done in desperation, as during peacetime cannibalism is much less frequent;[136] at other times, it is consciously directed at certain groups believed to be relatively helpless, such as Congo Pygmies, even considered subhuman by some other Congolese.[137]

Central African Republic

The self-declared emperor of the Central African Empire, Jean-Bédel Bokassa, was tried on October 24, 1986, for several cases of cannibalism although he was never convicted.[138][139] Between April 17 and April 19, 1979, a number of elementary school students were arrested after they had protested against wearing the expensive, government-required school uniforms. Around 100 were killed.[140] Bokassa is said to have participated in the massacre, beating some of the children to death with his cane and allegedly ate some of his victims.[141] In June 1987, he was cleared of charges of cannibalism, but found guilty of the murder of schoolchildren and other crimes.[142]

Further reports of cannibalism were reported against the Seleka Muslim minority during the ongoing Central African Republic conflict.[143][144]

South Sudan

During South Sudanese Civil War cannibalism and forced cannibalism have been reported.[145][146]

Uganda

In the 1970s the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin was reputed to practice cannibalism.[147][148] More recently, the Lord's Resistance Army has been accused of routinely engaging in ritual or magical cannibalism.[149] It is also reported by some that witch doctors sometimes use the body parts of children in their medicine.[150]

West Africa

In the 1980s, Médecins Sans Frontières, the international medical charity, supplied photographic and other documentary evidence of ritualized cannibal feasts among the participants in Liberia's internecine strife to representatives of Amnesty International who were on a fact-finding mission to the neighboring state of Guinea. However, Amnesty International declined to publicize this material; the Secretary-General of the organization, Pierre Sane, said at the time in an internal communication that "what they do with the bodies after human rights violations are committed is not part of our mandate or concern". The existence of cannibalism on a wide scale in Liberia was subsequently verified.[151]

United Kingdom

In 2008, a British model called Anthony Morley was imprisoned for the killing, dismemberment and partial cannibalisation of his lover, magazine executive Damian Oldfield. In 1996, Morley was a contestant on the television programme God's Gift; one of the audience members of that edition was Damian Oldfield. Oldfield was a contestant of another edition of the show in October 1996. On 2 May 2008, it was announced that Morley had been arrested for the murder of Oldfield, who worked for the gay lifestyle magazine Bent. After inviting Oldfield into his Leeds flat, police believed that Morley killed him, removed a section of his leg and began cooking it, before he stumbled into a nearby kebab house around 2:30 in the morning, drenched in blood and asking that someone call the police. He was found guilty on 17 October 2008 and sentenced to life imprisonment for the crime.[152][153][154]

Cambodia

Cannibalism was reported by the journalist Neil Davis during the South East Asian wars of the 1960s and 1970s. Davis reported that Cambodian troops ritually ate portions of the slain enemy, typically the liver. However he and many refugees also reported that cannibalism was practiced non-ritually when there was no food to be found. This usually occurred when towns and villages were under Khmer Rouge control, and food was strictly rationed, leading to widespread starvation. Any civilian caught participating in cannibalism would have been immediately executed.

China

Cannibalism is documented to have occurred in China during the Great Leap Forward, when rural China was hit hard by drought and famine.[155][156][157][158][159][160]

During Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution, local governments' documents revealed hundreds of incidents of cannibalism for ideological reasons. Public events for cannibalism were organised by local Communist Party officials, and people took part in them together in order to prove their revolutionary passion.[161][162] The writer Zheng Yi documented incidents of cannibalism in Guangxi in 1968 in his 1993 book, Scarlet Memorial: Tales of Cannibalism in Modern China.[163]

Germany

Karl Denke, Carl Großmann, Fritz Haarmann, Joachim Kroll, Peter Stumpp are of the many known German cannibals. Armin Meiwes, a former computer repair technician who achieved international notoriety for killing and eating a voluntary victim in 2001, whom he had found via the Internet. After Meiwes and the victim jointly attempted to eat the victim's severed penis, Meiwes killed his victim and proceeded to eat a large amount of his flesh. He was arrested in December 2002. In January 2004, Meiwes was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to eight years and six months in prison. In a retrial May 2006, he was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.[164] He reported that there are over 800 active cannibals in Germany.[165]

North Korea

Reports of widespread cannibalism began to emerge from North Korea during the famine of the 1990s[166][167] and subsequent ongoing starvation. Kim Jong-il was reported to have ordered a crackdown on cannibalism in 1996,[168] but Chinese travelers reported in 1998 that cannibalism had occurred.[169] Three people in North Korea were reported to have been executed for selling or eating human flesh in 2006.[170] Further reports of cannibalism emerged in early 2013, including reports of a man executed for killing his two children for food.[171][172][173]

There are competing claims about how widespread cannibalism was in North Korea. While refugees reported that it was widespread,[174] Barbara Demick wrote in her book, Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea (2010), that it did not seem to be.[175]

Tibet

Flesh pills were used by Tibetan Buddhists.[176] It was believed that mystical powers were bestowed upon people when they consumed Brahmin flesh.[177]

Russia

In his book, The Gulag Archipelago, Soviet writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn described cases of cannibalism in 20th-century Soviet Union.[178] Of the famine in Povolzhie (1921–1922) he wrote: "That horrible famine was up to cannibalism, up to consuming children by their own parents — the famine, which Russia had never known even in Time of Troubles [in 1601–1603]".[178]

Cannibalism was widespread during the Holodomor (famine of Ukraine) in 1932 and 1933.[179][180] During the 1930s, multiple acts of cannibalism were reported from Ukraine, Russia's Volga, South Siberian, and Kuban regions during the Soviet famine of 1932–1933.[181]

Survival was a moral as well as a physical struggle. A woman doctor wrote to a friend in June 1933 that she had not yet become a cannibal, but was "not sure that I shall not be one by the time my letter reaches you". The good people died first. Those who refused to steal or to prostitute themselves died. Those who gave food to others died. Those who refused to eat corpses died. Those who refused to kill their fellow man died. ... At least 2,505 people were sentenced for cannibalism in the years 1932 and 1933 in Ukraine, though the actual number of cases was certainly much higher.[182]

Solzhenitsyn said of the Siege of Leningrad (1941–1944): "Those who consumed human flesh, or dealt with the human liver trading from dissecting rooms ... were accounted as the political criminals".[183] And of the building of Northern Railway Labor Camp ("Sevzheldorlag") Solzhenitsyn reports, "An ordinary hard working political prisoner almost could not survive at that penal camp. In the camp Sevzheldorlag (chief: colonel Klyuchkin) in 1946–47 there were many cases of cannibalism: they cut human bodies, cooked and ate."[184]

The Soviet journalist Yevgenia Ginzburg was a long-term political prisoner who spent time in the Soviet prisons, Gulag camps and settlements from 1938 to 1955. She described in her memoir, Harsh Route (or Steep Route), of a case which she was directly involved in during the late 1940s, after she had been moved to the prisoners' hospital.[185]

The chief warder shows me the black smoked pot, filled with some food: "I need your medical expertise regarding this meat." I look into the pot, and hardly hold vomiting. The fibres of that meat are very small, and don't resemble me anything I have seen before. The skin on some pieces bristles with black hair ... A former smith from Poltava, Kulesh worked together with Centurashvili. At this time, Centurashvili was only one month away from being discharged from the camp ... And suddenly he surprisingly disappeared. The wardens looked around the hills, stated Kulesh's evidence, that last time Kulesh had seen his workmate near the fireplace, Kulesh went out to work and Centurashvili left to warm himself more; but when Kulesh returned to the fireplace, Centurashvili had vanished; who knows, maybe he got frozen somewhere in snow, he was a weak guy ... The wardens searched for two more days, and then assumed that it was an escape case, though they wondered why, since his imprisonment period was almost over ... The crime was there. Approaching the fireplace, Kulesh killed Centurashvili with an axe, burned his clothes, then dismembered him and hid the pieces in snow, in different places, putting specific marks on each burial place. ... Just yesterday, one body part was found under two crossed logs.

India

The Aghoris are Indian ascetics[186][187] who believe that eating human flesh confers spiritual and physical benefits, such as prevention of aging. They claim to only eat those who have voluntarily willed their body to the sect upon their death,[188] although an Indian TV crew witnessed one Aghori feasting on a corpse discovered floating in the Ganges,[189] and a member of the Dom caste reports that Aghoris often take bodies from the cremation ghat (or funeral pyre).[190]

Various cultures

The Korowai tribe of south-eastern Papua could be one of the last surviving tribes in the world engaging in cannibalism.[47] A local cannibal cult killed and ate victims as late as 2012.[12]

As in some other Papuan societies, the Urapmin people engaged in cannibalism in war. Notably, the Urapmin also had a system of food taboos wherein dogs could not be eaten and they had to be kept from breathing on food, unlike humans who could be eaten and with whom food could be shared.[191]

Individual acts

Prior to 1931, The New York Times reporter William Buehler Seabrook, in the interests of research, obtained from a hospital intern at the Sorbonne a chunk of human meat from the body of a healthy human killed in an accident, then cooked and ate it. He reported, "It was like good, fully developed veal, not young, but not yet beef. It was very definitely like that, and it was not like any other meat I had ever tasted. It was so nearly like good, fully developed veal that I think no person with a palate of ordinary, normal sensitiveness could distinguish it from veal. It was mild, good meat with no other sharply defined or highly characteristic taste such as for instance, goat, high game, and pork have. The steak was slightly tougher than prime veal, a little stringy, but not too tough or stringy to be agreeably edible. The roast, from which I cut and ate a central slice, was tender, and in color, texture, smell as well as taste, strengthened my certainty that of all the meats we habitually know, veal is the one meat to which this meat is accurately comparable."[192][193]

When Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 crashed into the Andes on October 13, 1972, the survivors resorted to eating the deceased during their 72 days in the mountains. Their story was later recounted in the books Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors (1974) and Miracle in the Andes: 72 Days on the Mountain and My Long Trek Home (2006), as well as the film Alive (1993), by Frank Marshall, and the documentaries Alive: 20 Years Later (1993) and Stranded: I've Come from a Plane that Crashed in the Mountains (2008).

On July 23, 1988, Rick Gibson ate the flesh of another person in public. Because England does not have a specific law against cannibalism, he legally ate a canapé of donated human tonsils in Walthamstow High Street, London.[194][195] A year later, on April 15, 1989, he publicly ate a slice of human testicle in Lewisham High Street, London.[196][197] When he tried to eat another slice of human testicle at the Pitt International Galleries in Vancouver on July 14, 1989, the Vancouver police confiscated the testicle hors d'œuvre.[198] However, the charge of publicly exhibiting a disgusting object was dropped, and he finally ate the piece of human testicle on the steps of the Vancouver court house on September 22, 1989.[199]

In 1992, Jeffrey Dahmer of Milwaukee, Wisconsin was arrested after one of his intended victims managed to escape. Found in Dahmer's apartment were two human hearts, an entire torso, a bag full of human organs from his victims, and a portion of arm muscle.[200] He stated that he planned to consume all of the body parts over the next few weeks.[201]

In 2001, Armin Meiwes from Essen, Germany killed and ate the flesh of a willing victim, Bernd Jürgen Brandis, as part of a sexual fantasy between the two. Despite Brandis' consent, which was documented on video, German courts convicted Meiwes of manslaughter, then murder, and sentenced him to life in prison.

See also

- Alexander Pearce

- Alferd Packer, an American prospector, accused but not convicted of cannibalism

- Androphagi, an ancient nation of cannibals

- Asmat people, a Papua group with a reputation of cannibalism

- Cannibalism in popular culture

- Cannibalism in poultry

- Chijon family, a Korean gang that killed and ate rich people

- Custom of the Sea, the practice of shipwrecked survivors drawing lots to see who would be killed and eaten so that the others might survive

- Homo antecessor, an extinct human species, suspected of practicing cannibalism

- Human fat has been applied in European pharmacopeia between the 16th and the 19th centuries.

- Human placentophagy, the consumption of the placenta (afterbirth)

- Idi Amin, Ugandan dictator who is alleged to have consumed humans.

- Issei Sagawa, a Japanese celebrity who killed and ate a fellow student

- List of incidents of cannibalism

- Manifesto Antropófago, (Cannibal Manifesto in English), a Brazilian poem

- Noida serial murders, a widely publicized instance of alleged cannibalism in India

- Placentophagy, the act of mammals eating the placenta of their young after childbirth

- Pleistocene human diet

- R v Dudley and Stephens, an important trial of two men accused of shipwreck cannibalism

- Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy, a progressive condition that affect the brain and nervous system of many animals, including humans

- Vorarephilia, a sexual fetish and paraphilia where arousal occurs from the idea of cannibalism

- Wari’ people, an Amerindian tribe that practiced cannibalism

References

- Brief history of cannibal controversies Archived February 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine; David F. Salisbury, August 15, 2001, Exploration, Vanderbuilt University.

- From primitive to post-colonial in Melanesia and anthropology. Bruce M. Knauft (1999). University of Michigan Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-472-06687-0

- Peggy Reeves Sanday. "Divine hunger: cannibalism as a cultural system".

- Rubinstein, W. D. (2004). Genocide: a history. Pearson Education. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-582-50601-5.

- Culotta, E. (October 1, 1999). "Neanderthals Were Cannibals, Bones Show". Science. Sciencemag.org. 286 (5437): 18b–19. doi:10.1126/science.286.5437.18b. PMID 10532879. S2CID 5696570.

- Gibbons, A. (August 1, 1997). "Archaeologists Rediscover Cannibals". Science. Sciencemag.org. 277 (5326): 635–37. doi:10.1126/science.277.5326.635. PMID 9254427. S2CID 38802004.

- McKie, Robin (May 17, 2009). "How Neanderthals met a grisly fate: devoured by humans". The Observer. London. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- Thompson, Jason (2008). A History of Egypt: From Earliest Times to the Present. American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774160912.

- Tannahill, Reay. (1996). Flesh and blood : a history of the cannibal complex (New and upd. ed.). Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 0-316-83705-9. OCLC 38036358.

- Liberia’s elections, ritual killings and cannibalism August 2011

- "UN condemns DR Congo cannibalism". BBC. January 15, 2003. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- "Cannibal cult members arrested in PNG". The New Zealand Herald. July 5, 2012. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- Raffaele, Paul (September 2006). "Sleeping with Cannibals". Smithsonian Magazine.

- Arens, William (April 26, 1979). The Man-Eating Myth : Anthropology and Anthropophagy: Anthropology and Anthropophagy. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780199763443.

- Sugg, Richard (2015): "Mummies, Vampires and Cannibals. The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians". Routdlege. pp. 122–125.

- Eat or be eaten: Is cannibalism a pathology as listed in the DSM-IV? The Straight Dope by Cecil Adams. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- "Cannibalism Definition". Dictionary.com.

- "cannibalism (human behaviour)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

- Woznicki, Andrew N. (1998). "Endocannibalism of the Yanomami". The Summit Times. 6 (18–19).

- Dow, James W. "Cannibalism". In Tenenbaum, Barbara A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture – Volume 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 535–537. Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- Goldman, Laurence, ed. (1999). The Anthropology of Cannibalism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-89789-596-5.

- "Anthropophagy". 1728 Cyclopaedia.

- Lindenbaum S (November 2008). "Understanding kuru: the contribution of anthropology and medicine". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363 (1510): 3715–20. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0072. PMC 2735506. PMID 18849287.

- Mead S, Stumpf MP, Whitfield J, et al. (April 2003). "Balancing selection at the prion protein gene consistent with prehistoric kurulike epidemics" (PDF). Science. 300 (5619): 640–43. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..640M. doi:10.1126/science.1083320. PMID 12690204. S2CID 19269845.

- Nicholas Wade (April 11, 2003). "Gene Study Finds Cannibal Pattern". New York Times.

- Roach, John (April 10, 2003). "Cannibalism Normal For Early Humans?". National Geographic.

- Soldevila M, Andrés AM, Ramírez-Soriano A, et al. (February 2006). "The prion protein gene in humans revisited: Lessons from a worldwide resequencing study". Genome Res. 16 (2): 231–9. doi:10.1101/gr.4345506. PMC 1361719. PMID 16369046.

- "No cannibalism signature in human gene". New Scientist.

- See Cannibalism – Some Hidden Truths Archived April 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine for an example documenting escaped convicts in Australia who initially blamed natives, but later confessed to conducting the practice themselves out of desperate hunger.

- Mead S, Whitfield J, Poulter M, et al. (November 2008). "Genetic susceptibility, evolution and the kuru epidemic". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363 (1510): 3741–46. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0087. PMC 2576515. PMID 18849290.

- Brightman, Robert A. (1988). "The Windigo in the Material World". Ethnohistory. 35 (4): 337–379. doi:10.2307/482140. JSTOR 482140.

- Gilmore, David D. (2009). Monsters : Evil Beings, Mythical Beasts and All Manner of Imaginary Terrors. Philadelphia, Pa.: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0812220889.

- (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979; ISBN 0-19-502793-0)

- Rebecca Earle, The Body of the Conquistador: Food, race, and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700. New York: Cambridge University Press 2012, pp. 123–24.

- Earle, The Body of the Conquistador, p. 123.

- Eskildsen, Robert (2002). "Of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan". The American Historical Review. 107 (2): 388–418. doi:10.1086/532291.

- "Tales of Maori cannibalism told in new book". Stuff.co.nz. NZPA. August 5, 2008. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- Tahana, Yvonne (July 12, 2008). "Cannibalism had little to do with consuming enemies' mana, says historian". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- John Byron, Samuel Wallis, Philip Carteret, James Cook, Joseph Banks (1785, 3d ed.). An account of the voyages undertaken by the order of His present Majesty for making discoveries in the southern hemisphere, vol. 3 (London) p. 295.

- "The edible dead". Britarch.ac.uk. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- Suelzle, Ben (November 2005). "Review of "The Origins of War: Violence in Prehistory", Jean Guilaine and Jean Zammit". ERAS Journal (7). Archived from the original on February 4, 2013.

- Kay A. Read, "Cannibalism" in Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, vol. 1, pp. 137–139. New York: Oxford University Press 2001.

- "Hans Staden Among the Tupinambas". Lehigh.edu. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- Unfortunate Emigrants: Narratives of the Donner Party, Utah State University Press. ISBN 0-87421-204-9

- "Māori Cannibalism". Retrieved July 27, 2007.

- "King of the Cannibal Isles". Time. May 11, 1942. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- Rafaele, Paul (September 2006). "Sleeping with Cannibals". Smithsonian Magazine.

- "Fijians find chutney in bad taste". BBC News. December 13, 1998. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- "CNN.com – Lab tests show evidence of cannibalism among ancient Indians – September 6, 2000". July 6, 2008. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008.

- "Anasazi Cannibalism?". Archaeology.org. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- Alexandra Witze (June 1, 2001). "Researchers Divided Over Whether Anasazi Were Cannibals". National Geographic. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Richard Hollingham (July 10, 2004). "Natural born cannibals". New Scientist: 30.

- Tim D white (September 15, 2006). Once were Cannibals. Evolution: A Scientific American Reader. ISBN 978-0-226-74269-4. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- James Owen. "Neandertals Turned to Cannibalism, Bone Cave Suggests". National Geographic News. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- Jordania, Joseph (2011). Why do People Sing? Music in Human Evolution. Logos. pp. 119–121.

- Corbett, Jim (2003). Man-Eaters of Kumaon. Oxford University Press, 26th impression. pp. xv–xvi.

- McKie, Robin (June 20, 2010). "Bones from a Cheddar Gorge cave show that cannibalism helped Britain's earliest settlers survive the ice age". The Guardian. London. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- Bello, Silvia M.; Wallduck, Rosalind; Parfitt, Simon A.; Stringer, Chris B. (August 9, 2017). "An Upper Palaeolithic engraved human bone associated with ritualistic cannibalism". PLoS ONE. 12 (8): e0182127. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1282127B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182127. PMC 5549908. PMID 28792978.

- Bello, Silvia M.; et al. (February 2011). Petraglia, Michael (ed.). "Earliest Directly-Dated Human Skull-Cups". PLoS ONE. 6 (2): e17026. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017026. PMC 3040189. PMID 21359211.

- Amos, Jonathan (February 16, 2011). "Ancient Britons 'drank from skulls'". BBC News. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- Cannibalistic Celts discovered in South Gloucestershire March 7, 2001

- "Druids Committed Human Sacrifice, Cannibalism?". National Geographic.

- The History of Herodotus VOL I. October 4, 2012. ISBN 9781480063860. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- Godley, A. D. (1920). Herodotus, with an English translation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. Hdt. 4.18. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- The Pyramid Texts – Cannibal Hymn

- Sextus Empiricus, Against the Ethicists Sections 192-194

- Louis Rawlings, Hannibal the Cannibal? Polybius on Barcid atrocities, Cardiff Historical Papers, 2007/9

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXXII.4

- Appian. The Wars in Spain, Chapter XV, Section 96. Translated by Horace White. Hosted at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Flavius Josephus. The Wars of the Jews, Book VI, Chapter 3, Section 4. Translated by William Whiston. Hosted at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Schaff, Philip; Wace, Henry, eds. (c. 393). "Against Jovinianus—Book II". A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church. 2nd. 6. New York: The Christian Literature Company (published 1893). p. 394. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- Maalouf, Amin (1984). The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 37–40. ISBN 978-0-8052-0898-6.

- Pennell, C.R. (1991). "Cannibalism in Early Modern North Africa". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 18 (2): 169–185. doi:10.1080/13530199108705536. JSTOR 196038.

- David., Waines (2010). The odyssey of Ibn Battuta : uncommon tales of a medieval adventurer. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845118051. OCLC 711000202.

- "Medieval Doctors and Their Patients". mummytombs.com. Archived from the original on November 29, 2007. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- Quotes from John Sanderson's Travels (1586) in Daly, Nicholas (1994). "That Obscure Object of Desire: Victorian Commodity Culture and Fictions of the Mummy". Novel: A Forum on Fiction. 28 (1): 24–51. doi:10.2307/1345912. JSTOR 1345912.

- Benn, Charles (2002). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-19-517665-0.

- Bashir, Shahzad (2006). "Shah Ismaʿil and the Qizilbash: Cannibalism in the Religious History of Early Safavid Iran". History of Religions. The University of Chicago. 45 (3): 235. doi:10.1086/503715. S2CID 163061429.

- To Aztecs, Cannibalism Was a Status Symbol, New York Times

- "Aztec Cannibalism: An Ecological Necessity?". Latinamericanstudies.org. Archived from the original on August 5, 2009. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- Ortiz de Montellano, Bernard R. (1978). "Aztec Cannibalism: An Ecological necessity?". Science. 200 (4342): 611–617. Bibcode:1978Sci...200..611O. doi:10.1126/science.200.4342.611. PMID 17812682. S2CID 35652641.

- The cannibal within By Lewis F. Petrinovich, Aldine Transaction (2000), ISBN 0-202-02048-7. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- Stromberg, Joseph (April 30, 2013). "Starving Settlers in Jamestown Colony Resorted to Cannibalism". Smithsonian.

- Rebecca Earle, The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race, and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700. New York: Cambridge University Press 2012, p. 123.

- Dow, James. "Cannibalism". Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture. 1: 535–37.

- Kay A. Read, "Cannibalism" in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerica, New York: Oxford University Press 2001, vol. 1 p. 138.

- De Landa, Diego (1978). Yucatán before and after the Conquest. Dover. p. 4.

-

- Métraux, Alfred (1949). "Warfare, Cannibalism, and Human Trophies". Handbook of South American Indians. 5: 383–409.

- E. Bowen, 1747: 532

- cannibalism, James WHITE, ed., Handbook of Indians of Canada, Published as an Appendix to the Tenth Report of the Geographic Board of Canada, Ottawa, 1913, 632p., pp. 77–78.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 184–185.

- M. King, The Penguin History of New Zealand, (London, 2003) 105.

- Diary of du Clesmeur. Historical records of NZ. Vol l1, Robert McNab

- Masters, Catherine (September 8, 2007). "'Battle rage' fed Maori cannibalism". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- HONGI HIKA (c. 1780–1828) Ngapuhi war chief, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- "Chapter 20: OPENING OF TITOKOWARU'S CAMPAIGN – NZETC". nzetc.victoria.ac.nz.

- "Melanesia Historical and Geographical: the Solomon Islands and the New Hebrides". Southern Cross (1). Church Army Press. London: 1950.

- Most Prolific Cannibal Guinness Book of World Records Internet Archive Wayback Machine 2004-09-29

- Peggy Reeves Sanday. "Divine hunger: cannibalism as a cultural system". p. 166.

- Alanna King, ed. (1987). Robert Louis Stevenson in the South Seas. Luzac Paragon House. pp. 45–50.

- "Long pig – Oxford Reference". www.oxfordreference.com. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- "The Wreck of the Whaleship Essex". BBC. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- Keenleyside, Anne. "The final days of the Franklin expedition: new skeletal evidence Arctic 50(1) 36-36 1997" (PDF). Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- Johnson, Kristin (ed.) (1996). Unfortunate Emigrants: Narratives of the Donner Party, Utah State University Press. ISBN 0-87421-204-9

- Rawson, Claude (April 16, 2000). "The Ultimate Taboo". The New York Times.

- National Library of Ireland, MS 36,201/3

- Pakenham, Thomas (1991). The Scramble for Africa: White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent From 1876 to 1912. New York: Perennial. pp. 439–449. ISBN 978-0-380-71999-0.

- Pakenham, 439

- Pakenham, 447

- Slade, Ruth, "King Leopold's Congo" (1962), p. 115, citing Lemery Papers, AMAA, in Pakenham, 447

- "The Leopard Men". Unexplainedstuff.com. January 10, 1948. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- "The Leopard Society — Africa in the mid 1900s". Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- "900-Day Siege of Leningrad". It.stlawu.edu. Archived from the original on March 1, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- "This Day in History 1941: Siege of Leningrad begins". History.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- Daniel Goldhagen, Hitler's Willing Executioners (p. 290) – "2.8 million young, healthy Soviet POWs" killed by the Germans, "mainly by starvation ... in less than eight months" of 1941–42, before "the decimation of Soviet POWs ... was stopped" and the Germans "began to use them as laborers".

- The treatment of Soviet POWs: Starvation, disease, and shootings, June 1941 – January 1942 USHMM

- David M. Crowe (2013). Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responses. Routledge, p. 87, ISBN 1317986822

- Petrinovich, Lewis F. (2000). The Cannibal Within (illustrated ed.). Aldine Transaction. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-202-02048-8.

- Beevor, Antony. Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege. Penguin Books, 1999.

- Schindley, Wanda; Makara, Petar (2005). Jasenovac: proceedings of the First International Conference and Exhibit on the Jasenovac Concentration Camps, October 29–31, 1997, Kingsborough Community College of the City University of New York. Dallas Pub. p. 149. ISBN 9780912011646.

- Jacobs, Steven L. (2009). Confronting Genocide: Judaism, Christianity, Islam. Lexington Books. p. 160. ISBN 9780739135891.

- Lituchy, Barry M. (2006). Jasenovac and the Holocaust in Yugoslavia: Analyses and Survivor Testimonies. Jasenovac Research Institute. p. 220. ISBN 9780975343203.

- Byford, Jovan (2014). "Remembering Jasenovac: Survivor Testimonies and the Cultural Dimension of Bearing Witness" (PDF). Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 28 (1): 58–84. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcu011. S2CID 145546608.

- "The Extradition of Nazi Criminals: Ryan, Artukovic, and Demjanjuk". Simon Wiesenthal Center. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Happell, Charles (2008). The Bone Man of Kokoda. Sydney: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-3836-2.

- Tanaka, Yuki. Hidden horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II, Westview Press, 1996, p. 127.

- Lord Russell of Liverpool (Edward Russell), The Knights of Bushido, a short history of Japanese War Crimes, Greenhill Books, 2002, p.121

- Welch, JM (April 2002). "Without a Hangman, Without a Rope: Navy War Crimes Trials After World War II" (PDF). International Journal of Naval History. 1 (1). Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- Bradley, James (2003). Flyboys: A True Story of Courage (1st ed.). Little, Brown and Company (Time Warner Book Group). ISBN 978-0-316-10584-2.

- Bradley, James (2004) [2003]. Flyboys: A True Story of Courage (softcover) (first ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Back Bay Books. pp. 229–230, 311, 404. ISBN 978-0-316-15943-2. Retrieved December 26, 2007.

- McCarthy, Terry (August 12, 1992). "Japanese troops 'ate flesh of enemies and civilians'". The Independent.

- "Documents claim cannibalism by Japanese World War II soldiers". United Press International. August 10, 1992.

- Sharma, Manimugdha S. (August 11, 2014). "Japanese ate Indian PoWs, used them as live targets in WWII – Times of India". The Times of India.

- "Mass Rape, Cannibalism, Dismemberment – UN Team Finds Atrocities in Congo War" (July 4, 2018). ChannelNewsAsia.com. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- Congo's Sexual Violence Goes 'Far Beyond Rape', July 31, 2007. The Washington Post.

- "Cannibals massacring pygmies: claim". Sydney Morning Herald. January 10, 2003. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- Paul Salopek, "Who Rules the Forest", National Geographic September 2005, p. 85

- "'Cannibal' dictator Bokassa given posthumous pardon". The Guardian. December 3, 2010

- "Cannibal Emperor Bokassa Buried in Central African Republic". Americancivilrightsreview.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- "'Good old days' under Bokassa?". BBC News. January 2, 2009

- Papa in the Dock Time

- Great World Trials, "The Jean-Bédel Bokassa Trial 1986–87", p=437-440.

- "Hatred turns into Cannibalism in CAR". NewsAfrica.co.uk. January 17, 2014. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- Flynn, Daniel (July 29, 2014). "Insight – Gold, diamonds feed Central African religious violence". Reuters.

- "Cannibalism, rape and death: trauma as South Sudan turns five". July 5, 2016 – via www.reuters.com.

- Susannah Cullinane. "South Sudan report details cannibalism, rapes". CNN.

- "2003: 'War criminal' Idi Amin dies". BBC News. August 16, 2003. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- Orizio, Riccardo (August 21, 2003). "Idi Amin's Exile Dream". New York Times. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- Gerson, Michael (June 6, 2008). "Africa's Messiah of Horror". The Washington Post.

This is ultimately the work and trademark of a single man: Joseph Kony, the most carnivorous killer since Idi Amin.

- Child Sacrifices on the Rise in Uganda as Witch Doctors Expand Their Practices Archived October 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine; Ahmed Kamara, January 8, 2010, Archived October 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine , Newstime Africa.

- Gillison, Gillian (November 13, 2006). "From Cannibalism to Genocide: The Work of Denial". The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. MIT Press Journals. 37 (3): 395–414. doi:10.1162/jinh.2007.37.3.395. S2CID 144521549.

- "God's Gift – UKGameshows". www.ukgameshows.com. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Video of edition of God's Gift featuring Oldfield".

- "20 October 2008. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2008". Archived from the original on October 23, 2008.

- Courtis, Stephane; Werth, Nicolas; et al. The Black Book of Communism. Harvard University Press.

- Chang, Jung. Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China. Touchstone Press.

- Ying, Hong. Daughter Of the River: An Autobiography. Grove Press.

- Becker, Jasper. Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine. Holt Press.

- Mao Tze Tung. History Channel.

- Kristof, Nicholas D; WuDunn, Sheryl (1994). China Wakes: the Struggle for the Soul of a Rising Power. Times Books. pp. 73–75. ISBN 978-0-8129-2252-3.

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (January 6, 1993). "A Tale of Red Guards and Cannibals". The New York Times.

- Sutton, Donald S. (January 1995). "Consuming Counterrevolution: The Ritual and Culture of Cannibalism in Wuxuan, Guangxi, China, May to July 1968". Comparative Studies in Society and History. Cambridge University Press. 37 (1): 136–172. doi:10.1017/S0010417500019575. JSTOR 179381.

- Zheng, Yi (2018). Scarlet Memorial: Tales Of Cannibalism In Modern China. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-97277-5.

- Cole, Jonathan (June 30, 2016), "The Man Who Lost His Body", Losing Touch, Oxford University Press, pp. 64–74, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198778875.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-877887-5

- Zaman, Bashiran; Soldz, Stephen (July 11, 2016). "Why Cannibal? Representation and Defense in the Meiwes "German Cannibal" Case". International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies. 14 (1): 69–80. doi:10.1002/aps.1492. ISSN 1742-3341.

- "Cannibalism Fears in Hungry North Korea". Reuters. April 28, 1997.

- "French aid workers report cannibalism in famine-stricken North Korea". Minnesota Daily. April 16, 1998. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- Bong Lee (2003). The Unfinished War: Korea. Algora Publishing. p. 249. ISBN 978-0875862187.

- The Times. April 13, 1998. p. 13.

- "North Korea 'executes three people found guilty of cannibalism'". The Telegraph. May 11, 2012.

- "North Korean cannibalism fears amid claims starving people forced to desperate measures". The Independent. January 28, 2013.

- "Starving North Koreans eating own kids, corpses". The Times of India. January 29, 2013.

- "New reports of starving North Koreans resorting to cannibalism come amid renewed tensions between Pyongyang and Washington". New York Daily News. January 29, 2013.

- Jasper Becker (2005). Rogue Regime: Kim Jong Il and the Looming Threat of North Korea. Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0198038108.

- "The Cannibals of North Korea". Washington Post. February 5, 2013.

- Bell, Christopher (May 24, 2016). "A Tibetan Ritual Master's Objects of Power". Dissertation Reviews.

- Gentry, J. (2013). Substance and Sense: Objects of Power in the Life, Writings, and Legacy of the Tibetan Ritual Master Sog bzlog pa Blo gros rgyal mtshan (PDF) (PhD Thesis). Harvard University. p. 69.

- A. Solzhenitsyn (1973), The Gulag Archipelago, Part I, Chapter 9.

- Сокур, Василий [Sokur, Vasily] (November 21, 2008). Выявленным во время голодомора людоедам ходившие по селам медицинские работники давали отравленные "приманки" — кусок мяса или хлеба. Facts and Commentaries (in Russian). Archived from the original on January 6, 2013.

- Várdy, Steven Béla; Várdy, Agnes Huszár (2007). "Cannibalism in Stalin's Russia and Mao's China" (PDF). East European Quarterly. 41 (2): 225.

- Lukov, Yaroslav (November 22, 2003). "Ukraine marks great famine anniversary". BBC News. Retrieved July 27, 2007.

- Timothy Snyder. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books, 2010, pp. 50–51. ISBN 0-465-00239-0

- A. Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, Part I, comments to Chapter 5

- A. Solzhenitsyn The Gulag Archipelago, Part III, Chapter 15

- Yevgenia Ginzburg, Harsh Route, Part 2, Chapter 23 "The Paradise On A Microscope View"

- Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin. p. 8. ISBN 9780143414216.

- Ian Charles Harris (1992). Contemporary Religions: A World Guide. Longman Current Affairs. p. 74. ISBN 9780582086951.

- Schumacher, Tim (2013). A New Religion. iUniverse. p. 66. ISBN 9781475938463.

- "Indian doc focuses on Hindu cannibal sect". Today.com. October 27, 2005.

- "Aghoris". Encounter. November 12, 2006. ABC.

- Robbins, Joel (2006). "Properties of Nature, Properties of Culture: Ownership, Recognition, and the Politics of Nature in a Papua New Guinea Society". In Biersack, Aletta; Greenberg, James (eds.). Reimagining Political Ecology. Duke University Press. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-8223-3672-3.

- Seabrook, William Bueller (1931). Jungle Ways. London, Bombay, Sydney: George G. Harrap and Company.

- Allen, Gary (1999). What is the Flavor of Human Flesh?. Corvallis, Oregon: Presented at the Symposium Cultural and Historical Aspects of Foods Oregon State University. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008.

- "Hard to stomach, but Rick eats human parts", Waltham Forest Guardian, London, United Kingdom, p. 6, July 29, 1988

- Young, Andrew (August 4, 1988), "Rick eats his mate's tonsils on a cracker!", The Sun, Plymouth, United Kingdom, p. 3

- White, Kim (April 14, 1989), "Now Rick's really gone nuts!", Guardian & Gazette Newspapers, London, United Kingdom, p. 8

- "Rick's food for thought", The Mercury, London, United Kingdom, p. 5, April 20, 1989

- Stueck, Wendy (July 15, 1989), "Would-be cannibal's appetizer confiscated", Vancouver Sun, Vancouver, Canada, pp. A7

- "No charges laid over artist's testicle claim", Vancouver Sun, Vancouver, Canada, pp. B1, August 22, 1988

- Masters, Brian (1993). The Shrine of Jeffrey Dahmer. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-340-59194-9.

- Masters, Brain (1993). The Shrine of Jeffrey Dahmer. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-59194-9.

Further reading

- Abler, Thomas S (1980). "Iroquois Cannibalism: Fact not Fiction". Ethnohistory. 27 (4): 309–16. doi:10.2307/481728. JSTOR 481728.

- Berdan, Frances F. The Aztecs of Central Mexico: An Imperial Society. New York 1982.

- Dole, Gertrude E (1962). "Endocannibalism among the Amahuaca Indians". Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences. 24 (2): 567–573. doi:10.1111/j.2164-0947.1962.tb01432.x.

- Earle, Rebecca. The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race, and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700. New York: Cambridge University Press 2012.

- Forsyth, Donald W (1983). "The Beginnings of Brazilian Anthropology: Jesuits and Tupinamba Cannibalism". Journal of Anthropological Research. 39 (2): 147–78. doi:10.1086/jar.39.2.3629965. S2CID 163258535.

- Harner, Michael (1977). "The Ecological Basis for Aztec Sacrifice". American Ethnologist. 4: 117–135. doi:10.1525/ae.1977.4.1.02a00070.

- Jáuregui, Carlos. Canibalia: Canibalismo, calibanismo, antropofagía cultural y consumo en América Latina. Madrid: Vervuert 2008.

- Lestringant, Frank. Cannibals: The Discovery and Representation of the Cannibal from Columbus to Jules Verne. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1997.

- Métraux, Alfred (1949). "Warfare, Cannibalism, and Human Trophies". Handbook of South American Indians. 5: 383–409.

- Ortiz de Montellano, Bernard R (1978). "Aztec Cannibalism: An Ecological Necessity?". Science. 200: 116–117.

- Ortiz de Montellano, Bernard R. Aztec Medicine, Health, and Nutrition. New Brunswick 1990.

- Read, Kay A. Time and Sacrifice in the Aztec Cosmos. Bloomington 1998.

- Sahlins, Marshall. "Cannibalism: An Exchange." New York Review of Books 26, no. 4 (March 22, 1979).

- Schutt, Bill. Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books 2017.

- Sturtevant, William C. "Cannibalism". The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia. 1: 93–96.

- Whitehead, Neil L (1984). "Carib, Cannibalism, the Historical Evidence". Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 70: 69–98. doi:10.3406/jsa.1984.2239.

External links

- Is there a relation between cannibalism and amyloidosis?

- All about Cannibalism: The Ancient Taboo in Modern Times (Cannibalism Psychology) at CrimeLibrary.com

- Cannibalism, Víctor Montoya

- The Straight Dope Notes arguing that routine cannibalism is myth

- Did a mob of angry Dutch kill and eat their prime minister? (from The Straight Dope)

- Harry J. Brown, 'Hans Staden among the Tupinambas.'

- Exhibition All Cannibals, curator Jeanette Zwingenberger, maison rouge, Fondation Antoine de Galbert, Paris, 11.2.-15.5, 2011. Me Collectors Room, Thomas Olbricht, Berlin, 27.5–11.9. 2011. art press 2, Tous Cannibales/ Cannibals All, n°20, février 2011.|