Architecture of metropolitan Detroit

The architecture of metropolitan Detroit continues to attract the attention of architects and preservationists alike.[1][2] With one of the world's recognizable skylines, Detroit's waterfront panorama shows a variety of architectural styles. The post-modern neogothic spires of One Detroit Center refer to designs of the city's historic Art Deco skyscrapers.[3] Together with the Renaissance Center, they form the city's distinctive skyline.

Detroit's architecture is recognized as being among the finest in the U.S. Detroit has one of the largest surviving collections of late-19th- and early-20th-century buildings in the U.S.[3] Because of the city's economic difficulties, the National Trust for Historic Preservation has listed many of Detroit's skyscrapers and buildings as some of America's most endangered landmarks.[4]

The suburbs contain some significant contemporary architecture and several historic estates.[5][6]

Skyscrapers

In the 1880s, Gilded Age architects such as Gordon Lloyd, Harry J. Rill, and others, who had designed churches and homes, turned their attention to office and commercial buildings. They designed some of Detroit's ornately stone-carved 19th-century tall buildings, many of which are still standing. Lloyd's Romanesque six-story iron-framed Wright-Kay (1891) at 1500 Woodward Ave and his R. H. Traver Building (1889) at 1211 Woodward are prime examples.[3] The Wright-Kay, or Schwankovsky Building, was among the first to have an electric elevator.[3] Rill designed the ornate Beaux-Arts facade of Detroit Cornice and Slate (1897) at 733 Antoine.[3] The six-story Romanesque Globe Tobacco Building (1888) at 407 E. Fort, built by Alexander Chapoton, is another of the city's early surviving commercial buildings. Detroit's Victorian-styled Randolph Street Historic District contains some of the city's oldest surviving commercial buildings. The commercial building at 1244 Randolph Street dates from the 1840s, a rare survivor from the Antebellum period. Most of Detroit's expansion and development took place later.[7]

At 12 stories, the steel-framed United Way Community Services Building (1895), at 1212 Griswold, originally known as the Chamber of Commerce Building, qualifies as Detroit's oldest existing skyscraper.[6][8] The 10-story Hammond Building (1889), now demolished, is considered the city's first historic skyscraper.[9] The Qube in the Detroit Financial District was developed on the Hammond Building site.[10]

The city has numerous architecturally significant late-19th- and early-20th-century buildings and skyscrapers.[3] Daniel Burnham, Louis Kamper, and the Smith Hinchman & Grylls firm are among the architects who designed some of the city's other important skyscrapers at the turn of the century which endure today. Burnham's three remaining Detroit skyscraper designs are the Neo-Classical styled Chrysler House (1912) — renovated in 2002, and the Neo-Renaissance Whitney (1915) and Ford (1909) buildings. Among their early projects, Smith Hinchman & Grylls designed the Neo-Gothic R.H. Fyfe Building (1919) at Woodward and Adams, now converted to a residential high-rise.[11]

Detroit has preserved numerous historic buildings that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The city has many historic structures needing restoration. The most significant of these is the Michigan Central Station (1913) by Warren & Wetmore and Reed & Stem; it was bought by Ford in 2018 and is to be the center of a major multi-use development.

During the Roaring Twenties, Detroit's historic skyline arose.[12] Louis Kamper designed the ornate Neo-Renaissance styled Book-Cadillac Hotel (1924), which was the world's tallest hotel when it opened.

The city's architectural legacy is rich in Art Deco style, with buildings constructed during the boom years of the 1920s. Joseph L. Hudson, the department store magnate, had commissioned architect Hugh Ferriss to produce a series of renderings depicting new buildings for the city skyline.[13] Hudson's Department Store window displayed the Ferriss drawings to commemorate its fiftieth anniversary, and to celebrate the opening in 1927 of a new building for the Detroit Institute of Arts, a Beaux-Arts, Italian Renaissance-styled structure.[13] Other architects created designs inspired by the Hugh Ferriss concepts, which included the Guardian Building, the David Stott Building, the J.L Hudson Building, and others.[11][13]

Albert Kahn Associates designed what is now Cadillac Place (1923) for General Motors, featuring Neo-Classical architecture. Kahn, sometimes called the "architect of Detroit", originally worked for John Scott, who designed the Wayne County Building (1897). It opened as the second-largest office building in the world.[6]

The seven Fisher brothers, who owned the automotive company Fisher Body, essentially gave architect Kahn a blank check to design and build the "most beautiful building in the world."[14] This was the Fisher Building (1927) which, with its detailed work, has been called the city's "largest art object." Its opulent three-story, barrel-vaulted lobby is constructed with forty different kinds of marble.[14][15][16] Albert Kahn Associates chief architect for the Fisher Building was Joseph Nathaniel French.[17] The Fisher Building and Cadillac Place are among the National Historic Landmarks in Detroit anchoring the city's historic New Center.

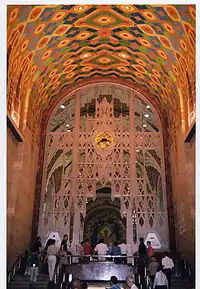

Architect Wirt C. Rowland played an integral role in crafting the city's historic skyline with his designs for the Buhl, Penobscot, and Guardian buildings. Rowland's design for the Buhl Building (1925) included a Gothic Revival design, with a blend of Romanesque accents. Renowned Art Deco skyscrapers include Rowland's Penobscot (1928) and Guardian (1929),[12] and John M. Donaldson's David Stott Building (1929). Architectural tiles made from Pewabic Pottery by American ceramist Mary Chase Perry Stratton are a prominent feature in the Guardian Building's facade and decor.[12]

Tallest buildings

| Rank | Building | Height | Stories | Built | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Detroit Marriott at the Renaissance Center | 727 feet (222 m) | 73 | 1977 | [18] | |

| 2 | One Detroit Center | 619 feet (189 m) | 43 | 1993 | [19] | |

| 3 | Penobscot Building | 565 feet (172 m) | 47 | 1928 | [20] | |

| T-4 | Renaissance Center Tower 100 | 522 feet (159 m) | 39 | 1977 | [21] | |

| T-4 | Renaissance Center Tower 200 | 522 feet (159 m) | 39 | 1977 | [22] | |

| T-4 | Renaissance Center Tower 300 | 522 feet (159 m) | 39 | 1977 | [23] | |

| T-4 | Renaissance Center Tower 400 | 522 feet (159 m) | 39 | 1977 | [24] | |

| 8 | Guardian Building | 496 feet (151 m) | 40 | 1929 | [25] | |

| 9 | Book Tower | 475 feet (145 m) | 38 | 1926 | [26] | |

| 10 | 150 West Jefferson | 455 feet (139 m) | 26 | 1989 | [27] |

Contemporary highlights

The Detroit area also contains prominent skycrapers designed in the Modern, Postmodern, and Contemporary Modern architectural styles.[3][6] With the notable exception of the 1001 Woodward (1965) building, Detroit's skyscrapers show less influence by the Chicago school of architecture and are more eastern in character.[3] Minoru Yamasaki designed Detroit's One Woodward Avenue (1962) in the Modern architectural style, following it with his similar, award-winning design for New York City's World Trade Center towers (1973-2001).[28] Today, the city's contemporary skyscrapers stand beside restored historic ones. One Detroit Center (1993) and its neogothic spires is considered a fine example of post modern architecture by architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee, referring to Wirt Rowland's historic Penobscot Building (1928), both located in the heart of the Financial District's wireless Internet zone.[3]

The office market in Metro Detroit is one of the nation's largest. with 147.88 million square feet (13,739,000 m2).[29] The Renaissance Center, with 5.552 million square feet (515,800 m2), and the Southfield Town Center, with 2.2 million square feet (204,400 m2), are large-scale examples of Contemporary Modern skyscraper complexes. Each mixed-use complex is an interconnected group of skyscrapers termed a "city within a city."

The construction of the Renaissance Center in Downtown Detroit marked a new era for the city's architecture. In the 1970s, Detroit Renaissance, chaired by Henry Ford II, commissioned highly regarded architect John Portman to design an enormous skyscraper complex called the Renaissance Center in hopes of increasing the attraction of city living for middle and upper-class residents. Some left because of court-ordered busing to integrate schools that were de facto segregated based on residential patterns. Portman had hoped to halt the exodus.

Portman expanded on his earlier design for the Peachtree Plaza Hotel in Atlanta when designing the Renaissance Center in Detroit. He contributed to the popularity of the skyscraper hotel.[3] (See Portman's Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles). In the ensuing decades, the Renaissance Center expanded to join the city's restored historic art deco skyscrapers in forming the current skyline.

In 1924, Detroit's Book-Cadillac opened as the world's tallest hotel (it is now a re-developed Westin Book-Cadillac Hotel). Completion of the first phase of the Renaissance Center in 1977 restored this distinction to the city. The Renaissance Center's central tower opened with a flagship hotel, the tallest in the world,[30] and a conference center with the world's largest rooftop restaurant. As of 2012 the hotel is Marriott International's largest in the United States, with 1,298 rooms. Though it is no longer the world's tallest hotel, it remains the tallest all-hotel skyscraper in the Western Hemisphere.[30] The Westin hotel and conference center at the Southfield Town Center is across from Lawrence Technological University.

Stemming the flight of capital from the city proved difficult, however, as the suburban office market continued to grow, notably in Southfield and Troy. The Southfield Town Center, constructed from 1975 to 1989, became easy to recognize with its marque of five golden glass skyscrapers. It attracted tenants in competition with the Renaissance Center as Metro Detroit's office market continued its suburban expansion.

Portman designed the Renaissance Center with interior spaces, yet secure. It quickly became a symbol of the city of Detroit. In 1996, the Renaissance Center's design changed when General Motors purchased the entire complex for its new headquarters. The $500-million makeover of the complex included a $100-million renovation of the hotel.[31] A new front door Wintergarden (2003) provides waterfront views and expanded retail space. Prior to completion of its renovation in 2003, some had criticized its circular corridors as confusing. Construction of a lighted glass walkway now facilitates ease of navigation encircling the interior mezzanine. A pedestrian-friendly glass entry way has replaced the former concrete berms along Jefferson Avenue.

The city, together with the Riverfront Conservancy, undertook another major project planned at $559-million along the Detroit International Riverfront to construct a three-mile (5 km) riverfront promenade park along the east river from Hart Plaza and the Renaissance Center to the Belle Isle bridge.[32] Detroit Wayne County Port Authority added the Dock of Detroit (2005), a state of the art cruise ship dock on Hart Plaza near the Renaissance Center. A two-mile (3 km) extension along the west river will take the riverfront promenade park from Hart Plaza to the Ambassador Bridge (1929) for a total of five miles (8 km) of parkway from bridge to bridge. Michigan constructed its first urban state park, the William G. Milliken State Park and Harbor (2003). Three contemporary high-rise casino resort hotels in Detroit include the MGM Grand Detroit (2007) by SmithGroup, Motor City Casino (2007), and the 30-story Greektown Casino (2009). A fourth contemporary high-rise casino resort hotel, Caesars Windsor (1998/2008), is visible from the International Riverfront.

Besides the Town Center skyscrapers, Southfield's modern towers include the 26-story American Center (1975) by the SmithGroup and One Towne Square (1992) by Rossetti with 21-stories. Other notable centers of commerce in the area are Dearborn, Troy, and Auburn Hills. Dearborn contains the world headquarters of the Ford Motor Company. Dearborn's 14-story luxury Adoba Hotel (1976) with its contemporary arced design by Charles Luckman is among the region's conference centers, with 772 rooms. Rossetti designed Dearborn's modern Ritz-Carlton Hotel (1988) along with the complementary Fairlane Plaza North and South (1990) as well as the Parklane Towers (1973). Troy has a large number of office buildings, many of which are situated along the corridor of Big Beaver Road. The tallest of these is the Top of Troy (1975) building, a 27-story triangular tower. Troy also contains what is generally considered to be the most upscale shopping center in the region, the Somerset Collection.

The suburb of Auburn Hills is home to the 15-story Chrysler Headquarters and Technology Center with its 5.3 million square feet (490,000 m2) on 504 acres (2.04 km2).[33] CRSS Architects designed the Chrysler Technology Center (1993) in a cross-axial formation where its elongated atrium topped concourses converge with an octagonal radiant skylight at its center. The SmithGroup designed the attached contemporary Chrysler Headquarters (1996) tower in golden glass crowned with the pentastar emblem. The nearby The Palace of Auburn Hills (1988) by Rosetti is a sports arena that has served as a prototype for many others of its kind.

Future development

Between 1996 and 2006, downtown Detroit attracted more than $15 billion in new investment from private and public sectors.[34] In 2011, Quicken Loans moved its company headquarters to downtown Detroit, consolidating suburban offices, a move considered to be of high importance to city planners to reestablish the historic downtown.[35] Quicken has purchased office buildings in downtown Detroit and has considered new sites for new construction at the former Statler on Grand Circus Park and the former Hudson's location.[35] Plans for a major residential and retail development adjacent to the Renaissance Center have been announced. In 2009, DTE unveiled a $50 million transformation of the landscape around its downtown headquarters into an urban oasis with parks, walkways, and a reflecting pool adjacent to the MGM Grand Detroit.[36] Many residential lofts and high rises are under construction in the Detroit area.[34] Renovation of historic buildings is a source of new development for the city of Detroit. The Inn at Ferry Street in the East Ferry Avenue Historic District and the Inn at 97 Winder in the Brush Park Historic District are examples of a successful Midtown restoration projects. Other historic restoration projects in Detroit include developments in the Midtown area, the Doubletree Guest Suites Fort Shelby, and the Westin Book-Cadillac Hotel. The Woodward Avenue Light Rail, beginning 2013, will serve as a link between the Detroit People Mover downtown and SEMCOG Commuter Rail with access to DDOT and SMART buses.[37]

In January 2008, the City of Detroit unveiled a concept for a new Cadillac Centre, a $150 million mixed-use residential entertainment-retail complex attached to the Cadillac Tower. Architect Anthony Caradonna designed the Cadillac Centre concept in the postmodern architectural genre known as deconstructivism similar to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. The 24-story steel and glass twin-towers complex to be located on Campus Martius has been placed on hold.[38] The futuristic Cadillac Centre would be located in Detroit's historic Monroe block, once a collection of eight antebellum commercial buildings cleared in 1990.[39] The Pavilions of Troy, a $380 million mixed-use complex, is concept planned for the suburban city of Troy.[40] Metro Detroit is second largest source of architectural and engineering job opportunities in the U.S.[41] The University of Michigan, the University of Detroit Mercy, and Lawrence Technological University offer architectural degree programs.

Landmarks and monuments

Founded in 1701, Detroit contains the second oldest Roman Catholic parish in the United States.[42] Consequently, Metro Detroit's many churches and cathedrals, though too numerous to list, are among its architectural gems and sites in the National Register of Historic Places. Churches dominated the city's post Civil War era skyline. The Gothic Revival architecture of Ste. Anne de Detroit Catholic Church (1887) by Alert E. French and Leon Coquard includes flying buttresses, displaying the French influence. Ste. Anne's displays the oldest stained glass in the city, located near the Ambassador Bridge.[6] The Gothic styled St. Joseph Church (1873/1883) in the Eastern Market-Lafayette Park neighborhood by Francis G. Himpler is an authentic German Catholic Parish and an important site listed in the National Register of Historic Places, noted for its architecture and stained glass.[6] In another German parish, Peter Dederichs designed the Pisan Romanesque styled Old St. Mary's Church (1885) in Greektown.[6] The Gothic Revival cathedral styled Sweetest Heart of Mary (1893) in the Forest Park neighborhood area by Spier and Rohns is the largest Roman Catholic Church in Detroit.[6][43]

The Gothic Revival styled Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament (1915) and the Cathedral Church of St. Paul (1911) by Ralph Adams Cram are both located along Woodward Avenue. Sculptor Corrado Parducci's work adorns many of Detroit's churches including the Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament and the St. Aloysius Church (1930) in the Washington Boulevard Historic District.[44] Among his Detroit projects, Gordon W. Lloyd designed the Christ Church (1863) at 960 E. Jefferson Avenue. Detroit's First Presbyterian Church (1891) is a fine example of Richardsonian Romanesque style by George D. Mason and Zachariah Rice. The Fort Street Presbyterian Church (1855), designed in a Victorian Gothic style with a steeple that rises 265 ft (81 m), is among the tallest churches in the United States.

The large concentration of Poles in the metropolitan Detroit resulted in a number of ornate churches in the Polish Cathedral style designed by noted architects. Henry Engelbert designed the Gothic styled St. Albertus (1885), Detroit's first Polish Catholic parish. Harry J. Rill designed St. Hedwig's (1915) and the Baroque styled St. Stanislaus (1913). Donaldson and Meier designed St. Hyacinth's (1924). Ralph Adams Cram designed the ornate Gothic styled St. Florian's Church (1928) at 2626 Poland Street in Hamtramck. Joseph G. Kastler and William B.N. Hunter designed the Victorian styled St. Josaphat's (1901) which has spires that line-up with the Renaissance Center towers when approaching the city on Interstate 75. The Historical Society at the Detroit Historical Museum provides information on tours of the area's many historic churches. The historic Beaubien House (c. 1851) at 553 East Jefferson houses the Michigan Society of Architects.

Campus Martius

The city and its surrounding area have numerous monuments by noted architects and sculptors along tree-lined boulevards and parks just some of which are noted.[45][46] Campus Martius is a park at the encircled confluence of Woodward and Michigan Avenues. It serves as one of the city's central gathering places for events. The park disappeared in the 1900s as the downtown reconfigured to accommodate increased vehicular traffic.[47] In 2004, the city restored the park with traffic circle. Granite waterfalls are at the western edge of the north and south sitting gardens. The park has two stages for live entertainment. Greenways and flowering botanical gardens fan out from Woodward Fountain, the centerpiece of Campus Martius, which can jet water over 100 feet (30 m) into the air,[48] while the Bagley Memorial Fountain sits nearby on Cadillac Square. Grand Circus is on Woodward Avenue, down the street.

Hart Plaza, along the riverfront, was designed to replace Campus Martius as a focal point. Yet Hart Plaza is a primarily hard-surfaced area, many residents came to lament the lack of true park space in the city's downtown area. This led to calls to rebuild Campus Martius. Compuware World Headquarters overlooks the reconstructed traffic circle surrounding Campus Martius Park with the historic Michigan Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument of the American Civil War by Randolph Rogers.[45] The old Detroit City Hall (1861) was demolished in 1961. It was built by Alexander Chapoton of one of the city's oldest French families. The Queen Anne style Alexander Chapoton House (c. 1870) stands at 511 Beaubien.[5][6]

Grand Circus

In 1805, Detroit experienced a devastating fire, which destroyed most of the city's French colonial architecture. Shortly afterward, Father Gabriel Richard said, Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus, meaning, We hope for better things; it will arise from the ashes, which became the city's official motto.[42] For Detroit, Justice Augustus B. Woodward devised a plan similar to Pierre Charles L'Enfant's design for Washington, D.C.. Detroit's monumental avenues and traffic circles fan out in a Baroque styled radial fashion from Grand Circus Park in the heart of the city's theater district.[49]

Detroit's performance centers and theatres emanate from the Grand Circus Park Historic District and continue along Woodward Avenue toward the Fisher Theatre in the city's New Center. The ornate Fox Theatre (1928), by C. Howard Crane, near the Grand Circus is a National Historic Landmark which was fully restored in 1988.[50] Crane also designed the Orchestra Hall along Woodward which is home to the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. In Gothic revival design, St. John's Episcopal Church (1861) stands across from the Fox Theatre and beside Comerica Park along with Woodward Avenue's vintage street lights. Restored in 1996, the Detroit Opera House (1922), by Crane, faces Grand Circus Park.[51] The grounds include antique statuary and old-fashioned water fountains. Architect Henry Bacon designed the Russell Alger Memorial Fountain (1921) in Grand Circus Park. The Russell Alger Memorial Fountain contains a classic Roman figure symbolizing Michigan by renowned American sculptor Daniel French.[45]

Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Classical

In the late 19th century, Detroit was called the Paris of the West for its architecture and open public spaces,[42] in keeping with the City Beautiful movement.[52] Architects John and Arthur Scott designed the Wayne County Building (1897) in downtown Detroit. Expense was not a factor in construction of its lavish design. Topped with bronze quadrigas by J. Massey Rhind and an Anthony Wayne pediment by Edward Wagner, it may be America's finest surviving example of Roman Baroque architecture with a blend of Beaux-Arts.[5] Stanford White, architect of Newport, Rhode Island's Rosecliff mansion, designed Detroit's Neoclassical Savoyard Centre (1900) at 151 Fort St. Belle Isle Park provides panoramic views of city skyline along the Detroit International Riverfront.

The French-American architect Paul Philippe Cret designed the Detroit Institute of Arts which includes a 1,150-seat theatre in the Detroit's Cultural Center Historic District. Cret was educated at the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon then in Paris, and came to the United States in 1903 to teach at the University of Pennsylvania. Cret was also the architect of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. Michael Graves designed the 2007 renovation and expansion of the Detroit Institute of Arts with its exterior covered in white marble. Harley, Ellington and Day designed the marble Neoclassical Horace Rackham Education Memorial Building (1941) also within the Cultural Center Historic District.

The Detroit area is home to light houses,[53] yacht clubs, and many unique monuments.[45] Examples include the Grosse Pointe Yacht Club (1929) and the Beaux-Arts Hurlbut Memorial Gate (1894) at Waterworks Park.[54] The Detroit Historical Society has compiled an incomplete list with more than 122 public sculptures and monuments just near the downtown area,[46] while Detroit1701 lists many additional downtown monuments.[55] Architects such as Cass Gilbert who designed the United States Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. also designed the marble Detroit Public Library (1921) in the Cultural Center Historic District and Belle Isle's exquisite marble James Scott Memorial Fountain.[56] Frederick Olmsted, landscape architect of New York City's Central Park, designed Detroit's 982-acre (3.97 km2) Belle Isle park. Marshall Fredericks' sculptures, which include the Spirit of Detroit, may be seen throughout the metropolitan area.[57] Sculptor Corrado Parducci's work adorns many notable Metro Detroit buildings such as the Meadowbrook Hall mansion, the Guardian Building, the Buhl Building (1925), the Penobscot Building, the Fisher Building and the David Stott Building.

Metro Detroit's many architecturally significant landmarks extend beyond the city and include the French Gothic St. Paul on the Lake Catholic Church (1899) by Harry J. Rill in Grosse Pointe Farms, Kirk in the Hills Presbyterian (1958) in Bloomfield Hills by Wirt C. Rowland, and Christ Church Cranbrook (1928) by Bertram Goodhue in Bloomfield Hills.[6]

Eliel Saarinen was the architect for the Cranbrook Educational Community in the Metro Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills.[6] Eliel's son, the famed modernist Eero Saarinen, designed a complex of buildings in the suburb of Warren, Michigan for General Motors known as the GM Technical Center.[6] Sculptor Carl Milles' numerous works in Metro Detroit include those at Cranbrook Educational Community in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan such as Mermaids & Tritons Fountain (1930), Sven Hedin on a Camel (1932), Jonah and the Whale Fountain (1932), Orpheus Fountain (1936), and the Spirit of Transportation (1952) at the Detroit Civic Center.[58]

Residential architecture

Downtown and New Center areas contain high-rise buildings, while the majority of the surrounding city consists of low-rise structures and single-family homes. The city's neighborhoods constructed prior to World War II feature the architecture of the times with wood frame and brick houses, larger brick homes in middle-class neighborhoods, and ornate mansions throughout the city's many historic districts and nearby suburbs such as Grosse Pointe. The oldest city neighborhoods are along the Woodward and Jefferson corridors, while newer city neighborhoods are found in the west and northeast.

High-rise residential buildings are found in neighborhoods along the International Riverfront and East Jefferson Avenue residential area extending toward Grosse Pointe and the Palmer Park neighborhood West of Woodward on the city's North end. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed a residential development for Detroit's East side Lafayette Park (1958–1965), including three high-rise residential buildings and over 200 townhouses. A successful 78-acre (320,000 m2) urban renewal project, this development is the largest concentration of buildings designed by Mies van der Rohe in the world.[60] Lafayette Park is near the architecturally significant St. Joseph's Catholic Church and the Eastern Market Historic District. The East side contains many architecturally distinctive homes such as those in the Indian Village and East Jefferson Avenue.

Some of the oldest extant working-class neighborhoods include those in the Southwest such Corktown, established by Irish immigrants and those in the middle-class West Vernor-Junction area. The Southwest is seeing redevelopment and construction of new homes and condos due in part to the city's expanding Mexicantown area surrounding Clark Park, which is near the architecturally significant Most Holy Redeemer Church and Ste. Anne de Detroit Catholic Church.

Detroit neighborhood historic districts contain notable residential architecture from the Gilded Age.[61] Many architecturally significant late-19th- and early-20th-century mansions have been restored, such as those in Midtown's Brush Park neighborhood. The West Canfield, Woodbridge, and East Ferry Avenue neighborhoods are examples of Midtown's restored French Renaissance Revival, Second Empire, Romanesque, and Queen Anne architecture. Noted architect Gordon W. Lloyd designed the David Whitney House (1894) constructed with a jasper stone exterior.[62] The Whitney House is now a fine restaurant at 4421 Woodward Avenue in Midtown. The East Canfield area nearby contains the Gothic revival styled Sweetest Heart of Mary Catholic Church.

Arden Park-East Boston (a National Historic district comprising Arden Park Boulevard and East Boston Boulevard, running for three blocks east of Woodward near the New Center Area) is noted for mansions built by the industrial giants of the 1910s and 1920s.[63] Residents included the Dodge Brothers, J. L. Hudson, and Fred Fisher, the founder of Fisher Body.[64] Fisher's residence on Arden Park (George D. Mason, 1918, with additions in 1923) is constructed of Indiana limestone in the Italian Villa style. It features elaborate stone carvings and intricate ironwork and was the subject of a 1926 "Fortune Magazine" discussion of "the harmony of materials and proportion in residential architecture." The nearby Boston-Edison neighborhood (comprising four residential blocks west of Woodward) features several Kahn residences, including the Benjamin Siegal residence (1915), the James Couzens house (1910), and one of Kahn's rare stucco residences, the Ernest Venn house (1908). Additional architecturally significant homes in the neighborhood include the Sebastian S. Kresge house, the Berry Gordy house, and one of the Henry Ford houses.[59] Many architecturally distinctive homes are also located near the University of Detroit Mercy on the city's North end such as those in Palmer Woods and Sherwood Forest historic districts. The Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament is located near this corridor along Woodward Avenue.

Detroit's heritage includes works by Frank Lloyd Wright who had participated in the initial design for Henry Ford's Fair Lane Estate,[65] a National Historic Landmark in Dearborn. Frank Lloyd Wright also designed the Dorothy H. Turkel House at 2760 West Seven Mile Rd.,[66] the Gregor S. and Elizabeth B. Affleck House at 1925 N. Woodward Ave., the Melvyn Maxwell and Sara Stein Smith House at 5045 Ponvalley Rd., and the Carlton D. Wall House at 12305 Beck Rd. in Plymouth Township.

The mansions of metropolitan Detroit are among the nation's grandest estates. Meadow Brook Hall (1929), the 110 room 88,000 sq ft (8,200 m2) mansion of Matilda Dodge Wilson at 480 South Adams Rd. in the suburb of Rochester Hills, is the fourth largest in the United States.[65] Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the mansion is open to the public. The suburbs of Grosse Pointe and Bloomfield Hills are replete with grandiose mansions. Albert Kahn designed the Edsel and Eleanor Ford House (1927) at 1100 Lakeshore Dr. in Grosse Pointe which is open to the public.[65] Rose Terrace (1934–1976), the mansion of Anna Dodge, once stood at 12 Lakeshore Dr. in Grosse Pointe. Designed by Horace Trumbauer as a Louis XV styled château, Rose Terrace was an enlarged version of the firm's Miramar in Newport, Rhode Island.[68] A developer, the highest bidder for Rose Terrace, demolished it in 1976 to create an upscale neighborhood. This gave a renewed sense of urgency to preservationists.[68] The Dodge Collection from Rose Terrace may be viewed at the Detroit Institute of Arts. The Italian Renaissance styled Russell A. Alger Jr., House (1910), at 32 Lakeshore Dr., by architect Charles A. Platt serves as the Grosse Pointe War Memorial.[69] The five Grosse Pointe communities feature a variety of newer and early-twentieth-century mansions which flank the shores of Lake St. Clair, one of the finest examples being Woodley Green (the Benson Ford House, 1934) by Hugh T. Keyes (considered "one of the most prolific and versatile architects of the period").[11] Bloomfield Hills also contains vast estates from the early to mid 20th century, such as Albert Kahn-designed Cranbrook House on Saarinen's Cranbrook campus (called by The New York Times "one of the greatest campuses ever created anywhere in the world"[70]). Next door on Vaughan Rd. is Keyes-designed Woodland, the estate of John Bugas.

There have also been some newer redeveloped upscale subdivisions in the Grosse Pointe, Bloomfield Hills, and Turtle Lake areas.[5][6][71]

Photo gallery

Skyscrapers

|

|---|

Landmarks

|

|---|

Monuments[45][46]

|

|---|

Architectural sculpture

|

|---|

Citations

- Aryamonti, Deborah Chatr (2006). "Review of Detroit and Rome: building on the past". Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2006.10.43. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- Detroit News (November 6, 2005).Detroit, ancient Rome share past.Model D Media. Retrieved on August 12, 2008.

- Sharoff, Robert (2005). American City: Detroit Architecture. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3270-6.

- Publisher review of American City: Detroit Architecture. Retrieved on November 24, 2007.

- Meyer, Katherine Mattingly and Martin C.P. McElroy with Introduction by W. Hawkins Ferry, Hon A.I.A. (1980). Detroit Architecture A.I.A. Guide Revised Edition. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1651-4.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Hill, Eric J.; John Gallagher (2002). AIA Detroit: The American Institute of Architects Guide to Detroit Architecture. Wayne State University Press.

- Randolph Street Commercial Buildings Historic District Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine from the state of Michigan, retrieved 01/02/11

- United Way Community Services Building.Emporis.com. Retrieved on November 23, 2007.

- "Hammond Building". Emporis.com. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- The Qube. Emporis. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- Ferry, W. Hawkins, The Buildings of Detroit: A History, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan, 1968

- Zacharias, Pat (March 9, 2001). Guardian Building has long been the crown jewel in the Detroit skyline. Michigan History, The Detroit News. Retrieved on April 12, 2014.

- Tottis, James W. (2008). The Guardian Building: Cathedral of Finance. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-3385-3.

- Houston, Kay and Linda Culpepper (March 20, 2001).The most beautiful building in the world Michigan History, The Detroit News. Retrieved on November 23, 2007

- Mazzei, Rebecca (November 30, 2005).Still Standing. Metro Times. Retrieved on November 23, 2007.

- AIA Detroit Urban Priorities Committee, (January 10, 2006).Top 10 Detroit Interiors.Model D Media. Retrieved on November 23, 2007.

- "Joseph N. French, Fairlane Architect". Detroit Free Press. March 2, 1975.

A graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he came to Detroit in 1913 to work as an architect on Henry Ford's home, Fairlane. He joined the architectural firm of Albert Kahn Associates in 1914 and retired from that company in 1967. In the meantime he had served as chief architect for the Fisher Building, taught methods of industrial construction in Russia and during World War II, designed installations for the Army and Navy throughout the world.

- "Detroit Marriott at the Renaissance Center". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "One Detroit Center". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "Penobscot Building". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "Renaissance Center Tower 100". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "Renaissance Center Tower 200". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "Renaissance Center Tower 300". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "Renaissance Center Tower 400". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "Guardian Building". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "Book Tower". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "150 West Jefferson". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- Baulch, Vivian M. (August 14, 1998)."Minoru Yamasaki, world-class architect". Michigan History, The Detroit News. Retrieved on November 23, 2007.

- Metro Detroit Office Market report. Colliers International. Retrieved on August 16, 2008.

- Official World's 100 Tallest High Rise Buildings (Hotel Use) Archived August 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Emporis.com. Retrieved on May 30, 2008.

- Mercer, Tenisha (October 19, 2005).GM's RenCen renovation attracts new business back. Detroit News. Retrieved on July 24, 2007.

- Detroit News Editorial (December 13, 2002). At Last, Sensible Dream for Detroit's Riverfront. Detroit News.

- Priddle, Alisa (May 12, 2009).Chrysler's tech center called a 'good asset'. The Detroit News. Retrieved on June 28, 2009.

- The Urban Markets Initiative, Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program The Social Compact, Inc. University of Michigan Graduate Real Estate Program (October 2006).Downtown Detroit In Focus: A Profile of Market Opportunity Archived September 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Downtown Detroit Partnership. Retrieved on January 4, 2011.

- Howes, Daniel (November 13, 2007).Quicken to move to Detroit. The Detroit News. Retrieved on June 23, 2009.

- July 4, 2007 Detroit News Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Downtown Detroit Partnership

- Ann Arbor - Detroit Regional Rail Project SEMCOG. Retrieved on February 4, 2010.

- PRNewswire (January 6, 2008).Detroit Gets New Era in Downtown Living With Iconic $150 Million Cadillac Centre on Campus Martius Park. Retrieved on January 13, 2008.

- Hyde, Charles (May–June 1991).Demolition by Neglect: The Failure to Save the Monroe Block Archived January 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.Michigan History Magazine. Retrieved on January 20, 2008.

- CB Richard Ellis - The Pavilions of Troy

- Automation Alley Technology Industry Report (2011 Edition) Archived 2015-07-05 at the Wayback Machine.Anderson Economic Group. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- Woodford, Arthur M. (2001). This is Detroit: 1701–2001. Wayne State University Press.

- Sweetest Heart of Mary Catholic Church from Detroit1701.org

- Foot, Andrew (June 29, 2006).International Metropolis Archived November 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrement. Diehl & Diehl Archives, photo inside Corrado Parducci's studio. Retrieved on July 24, 2009.

- Zacharias, Pat (September 5, 1999). Monuments of Detroit. Michigan History, Detroit News. Retrieved on November 21, 2007.

- Monuments and Sculptures in Detroit Archived July 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Detroit Historical Society. Retrieved on March 27, 2008.

- Condit, Julie (May 6, 2000).Campus Martius — city's heart may beat again. The Detroit News. Retrieved on August 12, 2008.

- Campus Martius Park. Detroit's Gathering Place — Park Grounds. Retrieved on August 12, 2008.

- Baulch, Vivian M. (June 13, 1999). Woodward Avenue, Detroit's Grand old "Main Street" Archived 2009-01-04 at Archive.today Michigan History, The Detroit News. Retrieved on November 23, 2007.

- Hodges, Michael H. (September 8, 2003).Fox Theater's rebirth ushered in city's renewal Archived December 5, 2012, at Archive.today. Michigan History, The Detroit News. Retrieved on November 23, 2007.

- DiChiera, David, Director.The Story of the Detroit Opera House Archived April 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.Michigan Opera Theatre. Retrieved on August 12, 2008.

- Bluestone, Daniel M., Columbia University, (September 1988).Detroit's City Beautiful and the Problem of Commerce Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. XLVII, No. 3, pp. 245–62. Retrieved on May 18, 2007.

- Lighthouses of the Great Lakes Archived October 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on November 23, 2007.

- Chauncey Hurlbut Memorial Gate Archived October 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Detroit 1701.org. Retrieved on November 24, 2007.

- Public Art and Sculpture, Detroit1701.org. Retrieved on March 28, 2008.

- James Scott Fountain Archived October 29, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Detroit 1701.org. Retrieved on November 24, 2007.

- Baulch, Vivian M. (August 4, 1998).Marshall Fredericks — the Spirit of Detroit Archived July 11, 2012, at Archive.today. Michigan History, The Detroit News. Retrieved on November 23, 2007.

- Baulch, Vivian M. (September 6, 1999).Carl Milles, Cranbrook's favorite sculptor. Michigan History, The Detroit News. Retrieved on November 23, 2007.

- Boston-Edison Historic District Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine from the City of Detroit Planning and Development Department.

- Vitullo-Martin, Julio (December 22, 2007).The Biggest Mies Collection: His Lafayette Park residential development thrives in Detroit.The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved on April 21, 2008.

- Detroit Historic Districts Archived 2012-06-15 at the Wayback Machine. Cityscape Detroit. Retrieved on December 16, 2007.

- David Whitney House Archived June 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine from the national Park Service

- Arden Park-East Boston Historic District. Detroit1701.org. Retrieved on December 16, 2007.

- Arden Park-East Boston Historic District Archived February 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. City of Detroit Planning and Development Department. Retrieved on December 16, 2007.

- A&E with Richard Guy Wilson, Ph.D.,(2000). America's Castles: The Auto Baron Estates, A&E Television Network.

- Michael Jackman (26 June 2006).Wright or wrong: Detroit's Turkel house drips with history. Metro Times

- McDonald, Maureen (November 28, 2006).Visit with a Giant. Model D Media. Retrieved on December 23, 2008.

- Zacharias, Patricia (June 24, 2000).Mrs. Dodge and the Regal Rose Terrace. Michigan History, The Detroit News. Retrieved on November 23, 2007.

- Grosse Pointe War Memorial, the Russell A. Alger Mansion. Retrieved on November 24, 2007.

- Paul Goldberger (April 8, 1984). "The Cranbrook Vision". The New York Times.

- Turtle Lake in Bloomfield Hills Archived May 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on November 24, 2007.

- Strother, Michael Guide to Ann Arbor Architecture Archived July 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine AIA Michigan. Retrieved on July 21, 2007.

References and further reading

- A&E with Richard Guy Wilson, Ph.D.,(2000). America's Castles: The Auto Baron Estates, A&E Television Network.

- A&E with Richard Guy Wilson, Ph.D.,(2000). America's Castles: Newspaper Moguls, Pittock Mansion, Cranbrook House & Gardens, The American Swedish Institute. A&E Television Network.

- Bridenstine, James (1989). Edsel and Eleanor Ford House. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2161-5.

- Collum, Marla O.; Barbara E. Krueger; Dorothy Kostuch (2012). Detroit's Historic Places of Worship. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0814334245.

- Delicato, Armando (2005). Italians in Detroit (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3985-6.

- Eckhert, Katheryn Bishop (1993). Buildings of Michigan (Society of Architectural Historians). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506149-7.

- Ferry, W. Hawkins (1968). The Buildings of Detroit: A History. Wayne State University Press.

- Fisher, Dale (1996). Ann Arbor: Visions of the Eagle. Grass Lake, Michigan: Eyry of the Eagle Publishing. ISBN 0-9615623-4-X.

- Fisher, Dale (2003). Building Michigan: A Tribute to Michigan's Construction Industry. Grass Lake, Michigan: Eyry of the Eagle Publishing. ISBN 1-891143-24-7.

- Fisher, Dale (2005). Southeast Michigan: Horizons of Growth. Grass Lake, Michigan: Eyry of the Eagle Publishing. ISBN 1-891143-25-5.

- Fisher, Dale (1994). Detroit: Visions of the Eagle. Grass Lake, Michigan: Eyry of the Eagle Publishing. ISBN 0-9615623-3-1.

- Fogelman, Randall (2004). Detroit's New Center. Arcadia. ISBN 0-7385-3271-1.

- Gallagher, John; Balthazar Korab (2008). Great Architecture of Michigan. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-9816144-0-3.

- Godzak, Roman (2004). Catholic Churches of Detroit (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3235-5.

- Hardwick, M. Jeffrey (2003). Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of the American Dream. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3762-5.

- Hauser, Michael; Marianne Weldon (2006). Downtown Detroit's Movie Palaces (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-4102-8.

- Eric J. Hill; John Gallagher (2002). AIA Detroit: The American Institute of Architects Guide to Detroit Architecture. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3120-3.

- Kavanaugh, Kelli B. (2001). Detroit's Michigan Central Station (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-1881-6.

- Kvaran, Einar Einarsson, Architectural Sculpture of America, unpublished manuscript

- Meyer, Katherine Mattingly and Martin C.P. McElroy with Introduction by W. Hawkins Ferry, Hon A.I.A. (1980). Detroit Architecture A.I.A. Guide Revised Edition. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1651-4.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Matuz, Roger (2007). Albert Kahn, Architect of Detroit. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2956-6.

- Nawrocki, Dennis Alan and Thomas J. Holleman (1980). Art in Detroit Public Places. Wayne State University Press.

- Portman, John; Jonathan Barnett (1976). The Architect as Developer. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-050536-5.

- Rodriguez, Michael; Thomas Featherstone (2003). Detroit's Belle Isle Island Park Gem (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-2315-1.

- Sharoff, Robert (2005). American City: Detroit Architecture. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3270-6.

- Savage, Rebecca Binno; Greg Kowalski (2004). Art Deco in Detroit (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3228-2.

- Sobocinski, Melanie Grunow (2005). Detroit and Rome: building on the past. Regents of the University of Michigan. ISBN 0-933691-09-2.

- Socia, Madeleine; Suzie Berschback (2001). Grosse Pointe: 1890–1930 (Images of America). Arcadia. ISBN 0-7385-0840-3.

- Tottis, James W. (2008). The Guardian Building: Cathedral of Finance. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-3385-3.

- Tutag, Nola Huse; Hamilton, Lucy (1988). Discovering Stained Glass in Detroit. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1875-4.

- Walt, Irene; Balthazar Korab (2004). Art in Stations. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-9745392-0-1.

- Woodford, Arthur M. (2001). This is Detroit 1701–2001. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2914-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of metropolitan Detroit. |

- AIA Detroit

- Buildings of Detroit (historic) and architects

- Cityscape Detroit

- Detroit 1701

- Detroit Midtown

- Detroit Riverfront Conservancy

- Experience Detroit

- Edsel & Eleanor Ford House

- Grosse Pointe Historical Society

- Henry Ford's Fair Lane Estate

- Images of Metro Detroit

- Model D Media

- New Center Council

- Downtown Detroit Partnership

- Oakland Regional Historic Sites

.svg.png.webp)