Toledo, Ohio

Toledo (/təˈliːdoʊ/) is a city in and the county seat of Lucas County, Ohio, United States.[7] A major Midwestern United States port city, Toledo is the fourth-most-populous city in the U.S. state of Ohio, after Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, and according to the 2010 census, the 71st-largest city in the United States. With a population of 274,975, it is the principal city of the Toledo metropolitan area. It also serves as a major trade center for the Midwest; its port is the fifth busiest in the Great Lakes and 54th biggest in the United States.[8][9] The city was founded in 1833 on the west bank of the Maumee River, and originally incorporated as part of Monroe County, Michigan Territory. It was re-founded in 1837, after the conclusion of the Toledo War, when it was incorporated in Ohio.

Toledo, Ohio | |

|---|---|

| City of Toledo | |

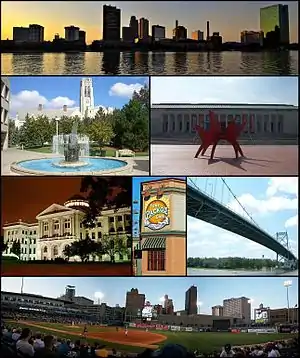

Images, from top left to right: Downtown Toledo, University Hall, Toledo Museum of Art, Lucas County Courthouse, Tony Packo's Cafe, Anthony Wayne Bridge, Fifth Third Field | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The Glass City | |

| Motto(s): "Laborare est Orare" (To Work is to Pray)[1] | |

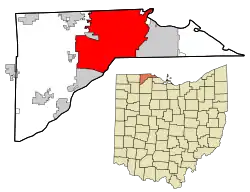

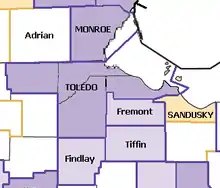

Location of Toledo within Lucas County, Ohio | |

Toledo Location of Toledo within Lucas County, Ohio  Toledo Toledo (the United States)  Toledo Toledo (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 41°39′56″N 83°34′31″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Lucas |

| Founded | 1833 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Wade Kapszukiewicz (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 83.83 sq mi (217.13 km2) |

| • Land | 80.49 sq mi (208.47 km2) |

| • Water | 3.34 sq mi (8.66 km2) |

| Elevation | 614 ft (187 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 287,208 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 272,779 |

| • Rank | US: 76th |

| • Density | 3,388.94/sq mi (1,308.48/km2) |

| • Urban | 507,643 (US: 80th) |

| • Metro | 608,145 (US: 89th) |

| Demonym(s) | Toledoan |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | Zip codes[5]

|

| Area codes | 419, 567 |

| FIPS code | 39-77000 |

| GNIS ID | 1067015[6] |

| Website | www.toledo.oh.gov |

After the 1845 completion of the Miami and Erie Canal, Toledo grew quickly; it also benefited from its position on the railway line between New York City and Chicago. The first of many glass manufacturers arrived in the 1880s, eventually earning Toledo its nickname: "The Glass City." It has since become a city with a distinctive and growing art community, auto assembly businesses, education, thriving healthcare, and well-supported local sports teams. Downtown Toledo has been subject to major revitalization efforts, allowing a bustling entertainment district.

History

The region was part of a larger area controlled by the historic tribes of the Wyandot and the people of the Council of Three Fires (Ojibwe, Potawatomi and Odawa). The French established trading posts in the area by 1680 to take advantage of the lucrative fur trade. The Odawa moved from Manitoulin Island and the Bruce Peninsula at the invitation of the French, who established a trading post at Fort Detroit, about 60 miles to the north. They settled an area extending into northwest Ohio. By the early 18th century, the Odawa occupied areas along most of the Maumee River to its mouth. They served as middlemen between the French and tribes further to the west and north. The Wyandot occupied central Ohio, and the Shawnee and Lenape occupied the southern areas.[10][11]

When the city of Toledo was preparing to pave its streets, it surveyed "two prehistoric semicircular earthworks, presumably for stockades." One was at the intersection of Clayton and Oliver streets on the south bank of Swan Creek; the other was at the intersection of Fassett and Fort streets on the right bank of the Maumee River.[12] Such earthworks were typical of mound-building peoples.

19th century

According to Charles E. Slocum, the American military built Fort Industry at the mouth of Swan Creek about 1805, as a temporary stockade. No official reports support the 19th-century tradition of its earlier history there.[12]

The United States continued to work to extinguish land claims of Native Americans. In the Treaty of Detroit (1807), the above four tribes ceded a large land area to the United States of what became southeastern Michigan and northwestern Ohio, to the mouth of the Maumee River (where Toledo later developed). Reserves for the Odawa were set aside in northwestern Ohio for a limited period of time. The Native Americans signed the treaty at Detroit, Michigan, on November 17, 1807, with William Hull, governor of the Michigan Territory and superintendent of Indian affairs, as the sole representative of the U.S.[13]

.jpg.webp)

More European-American settlers entered the area over the next few years, but many fled during the War of 1812, when British forces raided the area with their Indian allies. Resettlement began around 1818 after a Cincinnati syndicate purchased a 974-acre (3.9 km2) tract at the mouth of Swan Creek and named it Port Lawrence, developing it as the modern downtown area of Toledo. Immediately to the north of that, another syndicate founded the town of Vistula, the historic north end.[14] These two towns bordered each other across Cherry Street. This is why present-day streets on the street's northeast side run at a slightly different angle from those southwest of it.

In 1824, the Ohio state legislature authorized the construction of the Miami and Erie Canal and in 1833, its Wabash and Erie Canal extension. The canal's purpose was to connect the city of Cincinnati to Lake Erie for water transportation to eastern markets, including to New York City via the Erie Canal and Hudson River. At that time no highways had been built in the state, and it was very difficult for goods produced locally to reach the larger markets east of the Appalachian Mountains. During the canal's planning phase, many small towns along the northern shores of Maumee River heavily competed to be the ending terminus of the canal, knowing it would give them a profitable status.[15] The towns of Port Lawrence and Vistula merged in 1833 to better compete against the upriver towns of Waterville and Maumee.

The inhabitants of this joined settlement chose the name Toledo:

"but the reason for this choice is buried in a welter of legends. One recounts that Washington Irving, who was traveling in Spain at the time, suggested the name to his brother, a local resident; this explanation ignores the fact that Irving returned to the United States in 1832. Others award the honor to Two Stickney, son of the major who quaintly numbered his sons and named his daughters after States. The most popular version attributes the naming to Willard J. Daniels, a merchant, who reportedly suggested Toledo because it 'is easy to pronounce, is pleasant in sound, and there is no other city of that name on the American continent.'"[14]

Despite Toledo's efforts, the canal built the final terminus in Manhattan, one-half mile (800 m) to the north of Toledo, because it was closer to Lake Erie. As a compromise, the state placed two sidecuts before the terminus, one in Toledo at Swan Creek and another in Maumee, about 10 miles to the southwest.

Among the numerous treaties made between the Ottawa and the United States were two signed in this area: at Miami (Maumee) Bay in 1831 and Maumee, Ohio, upriver of Toledo, in 1833.[16] These actions were among US purchases or exchanges of land in order to accomplish Indian Removal of the Ottawa from areas wanted for European-American settlement. The last of the Odawa did not leave this area until 1839, when Ottokee, grandson of Pontiac, led his band from their village at the mouth of the Maumee River to Indian Territory in Kansas.[17][18]

An almost bloodless conflict between Ohio and the Michigan Territory, called the Toledo War (1835–1836), was "fought" over a narrow strip of land from the Indiana border to Lake Erie, now containing the city and the suburbs of Sylvania and Oregon, Ohio. The strip—which varied between five and eight miles (13 km) in width—was claimed by both the state of Ohio and the Michigan Territory due to conflicting legislation concerning the location of the Ohio-Michigan state line. Militias from both states were sent to the border but never engaged. The only casualty of the conflict was a Michigan deputy sheriff—stabbed in the leg with a pen knife by Two Stickney during the arrest of his elder brother, One Stickney—and the loss of two horses, two pigs and a few chickens stolen from an Ohio farm by lost members of the Michigan militia. Major Benjamin Franklin Stickney, father of One and Two Stickney, had been instrumental in pushing Congress to rule in favor of Ohio gaining Toledo.[19] In the end, the state of Ohio was awarded the land after the state of Michigan was given a larger portion of the Upper Peninsula in exchange.[20] Stickney Avenue in Toledo is named for Major Stickney.

Toledo was very slow to expand during its first two decades of settlement. The first lot was sold in the Port Lawrence section of the city in 1833. It held 1,205 persons in 1835, and five years later it had gained just seven more persons. Settlers came and went quickly through Toledo and between 1833 and 1836, ownership of land had changed so many times that none of the original parties remained in the town. The canal and its Toledo sidecut entrance were completed in 1843. Soon after the canal was functional, the new canal boats had become too large to use the shallow waters at the terminus in Manhattan. More boats began using the Swan Creek sidecut than its official terminus, quickly putting the Manhattan warehouses out of business and triggering a rush to move business to Toledo. Most of Manhattan's residents moved out by 1844.

The 1850 census recorded Toledo as having 3,829 residents and Manhattan 541. The 1860 census shows Toledo with a population of 13,768 and Manhattan with 788. While the towns were only a mile apart, Toledo grew by 359% in ten years. Manhattan's growth was on a small base and never competed, given the drawbacks of its lesser canal outlet. By the 1880s, Toledo expanded over the vacant streets of Manhattan and Tremainsville, a small town to the west.[15][21]

In the last half of the 19th century, railroads slowly began to replace canals as the major form of transportation. They were faster and had greater capacity. Toledo soon became a hub for several railroad companies and a hotspot for industries such as furniture producers, carriage makers, breweries, glass manufacturers, and others. Large immigrant populations came to the area.

20th century

In the 1920s, Toledo had one of the highest rates of industrial growth in the United States.[22]

Toledo continued to expand in population and industry, but because of its dependence on manufacturing, the city was hit hard by the Great Depression. Many large-scale WPA projects were constructed to reemploy citizens in the 1930s. Some of these include the amphitheater and aquarium at the Toledo Zoo and a major expansion to the Toledo Museum of Art.

.jpg.webp)

The post-war job boom and Great Migration brought thousands of African Americans to Toledo to work in industrial jobs, where they had previously been denied. Due to redlining, many of them settled along Dorr Street, which, during the 1950s and 60s was lined with flourishing black-owned businesses and homes. Desegregation, a failed urban renewal project, and the construction of I-75 displaced those residents and left behind a struggling community with minimal resources, even as it also drew more established, middle-class people, white and black, out of center cities for newer housing.[23] The city rebounded, but the slump of American manufacturing in the second half of the 20th century during industrial restructuring cost many jobs.

By the 1980s, Toledo had a depressed economy.[24] The destruction of many buildings downtown, along with several failed business ventures in housing in the core, led to a reverse city-suburb wealth problem common in small cities with land to spare.

21st century

In 2018, Cleveland-Cliffs, Inc. invested $700 million into an East Toledo location as the site of a new hot-briquetted iron plant, designed to modernize the steel industry. The plant is slated to create over 1200 jobs and be completed in 2020.[25]

Several initiatives have been taken by Toledo's citizens to improve the cityscape by urban gardening and revitalizing their communities.[26] Local artists, supported by organizations like the Arts Commission of Greater Toledo and the Ohio Arts Council, have contributed an array of murals and beautification works to replace long standing blight.[27] Many downtown historical buildings such as the Oliver House and Standart Lofts have been renovated into restaurants, condominiums, offices and art galleries.[28]

Geography

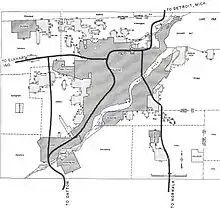

Toledo is located at 41°39′56″N 83°34′31″W (41.665682, −83.575337).[29] The city has a total area of 84.12 square miles (217.87 km2), of which 80.69 square miles (208.99 km2) is land and 3.43 square miles (8.88 km2) is water.[30]

The city straddles the Maumee River at its mouth at the southern end of Maumee Bay, the westernmost inlet of Lake Erie. The city is located north of what had been the Great Black Swamp, giving rise to another nickname, Frog Town. Toledo sits within the borders of a sandy oak savanna called the Oak Openings Region, an important ecological site that once comprised more than 300 square miles (780 km2).[31]

Toledo is within 250 miles (400 km) by road from seven metro areas that have a population of more than two million people; they are Detroit, Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, and Chicago.

Climate

Toledo, as with much of the Great Lakes region, has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), characterized by four distinct seasons. Lake Erie moderates the climate somewhat, especially in late spring and fall, when air and water temperature differences are maximal. However, this effect is lessened in the winter because Lake Erie (unlike the other Great Lakes) usually freezes over, coupled with prevailing winds that are often westerly. And in the summer, prevailing winds south and west over the lake bring heat and moisture to the city.

Summers are very warm and humid, with July averaging 73.5 °F (23.1 °C) and temperatures of 90 °F (32 °C) or more seen on 16.5 days.[32] Winters are cold and somewhat snowy, with a January mean temperature of 25.5 °F (−3.6 °C), and lows at or below 0 °F (−18 °C) on 6.2 nights.[32] The spring months tend to be the wettest time of year, although precipitation is common year-round. November and December can get very cloudy, but January and February usually clear up after the lake freezes. July is the sunniest month overall.[33] About 37 inches (94 cm) of snow falls per year, much less than the Snow Belt cities, because of the prevailing wind direction. Temperature extremes have ranged from −20 °F (−29 °C) on January 21, 1984, to 105 °F (41 °C) on July 14, 1936.

| Climate data for Toledo, Ohio (Toledo Express Airport), 1981−2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1871−present[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

71 (22) |

85 (29) |

89 (32) |

98 (37) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

92 (33) |

80 (27) |

70 (21) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 53.1 (11.7) |

56.9 (13.8) |

71.5 (21.9) |

81.2 (27.3) |

87.0 (30.6) |

93.4 (34.1) |

94.3 (34.6) |

92.2 (33.4) |

89.4 (31.9) |

80.9 (27.2) |

68.8 (20.4) |

55.9 (13.3) |

95.8 (35.4) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 32.6 (0.3) |

36.0 (2.2) |

46.9 (8.3) |

60.1 (15.6) |

71.0 (21.7) |

80.7 (27.1) |

84.5 (29.2) |

82.2 (27.9) |

75.4 (24.1) |

62.8 (17.1) |

49.7 (9.8) |

36.4 (2.4) |

60.0 (15.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 18.4 (−7.6) |

20.6 (−6.3) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

38.7 (3.7) |

48.5 (9.2) |

58.3 (14.6) |

62.4 (16.9) |

60.9 (16.1) |

52.8 (11.6) |

41.8 (5.4) |

33.2 (0.7) |

23.1 (−4.9) |

40.7 (4.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −2.8 (−19.3) |

1.6 (−16.9) |

9.7 (−12.4) |

23.1 (−4.9) |

34.4 (1.3) |

43.7 (6.5) |

49.8 (9.9) |

48.3 (9.1) |

37.3 (2.9) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

2.7 (−16.3) |

−7.0 (−21.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −20 (−29) |

−19 (−28) |

−10 (−23) |

8 (−13) |

25 (−4) |

32 (0) |

40 (4) |

34 (1) |

26 (−3) |

15 (−9) |

2 (−17) |

−19 (−28) |

−20 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.05 (52) |

2.07 (53) |

2.48 (63) |

3.19 (81) |

3.58 (91) |

3.57 (91) |

3.23 (82) |

3.15 (80) |

2.78 (71) |

2.60 (66) |

2.86 (73) |

2.68 (68) |

34.24 (870) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 11.6 (29) |

9.4 (24) |

5.7 (14) |

1.3 (3.3) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.9 (4.8) |

7.4 (19) |

37.6 (96) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12.7 | 10.2 | 11.8 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 11.4 | 13.1 | 132.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 9.3 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 2.3 | 7.9 | 33.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.2 | 72.9 | 70.5 | 66.2 | 66.3 | 69.0 | 71.8 | 75.6 | 76.2 | 72.5 | 75.6 | 78.6 | 72.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 126.0 | 142.2 | 183.7 | 213.7 | 265.9 | 288.2 | 299.3 | 263.7 | 220.3 | 180.4 | 106.5 | 90.2 | 2,380.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 43 | 48 | 50 | 53 | 59 | 63 | 65 | 62 | 59 | 52 | 36 | 32 | 53 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961−1990)[34][32][35][33] and Weather Atlas[36] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Neighborhoods and suburbs

The Old West End is a historic neighborhood of Victorian, Arts & Crafts, and other Edwardian-style houses. The historic district is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Beverly

- Birmingham

- DeVeaux

- Crossgates

- Five Points

- Downtown

- East Toledo

- Franklin Park

- Garfield

- Glendale-Heatherdowns (Byrne-Heatherdowns Village)

- Harvard Terrace

- Library Village

- North Towne

- Old Orchard

- Old West End

- Old South End

- Old Town

- ONE Village (includes the Polish International Village, Vistula, & North River)

- ONYX (includes historic Kuschwantz and Lenk's Hill neighborhoods)

- Ottawa

- Point Place

- Reynolds Corners

- Roosevelt

- Scott Park

- Secor Gardens (includes the University of Toledo)

- Southwyck

- Wernert's Corner

- Trilby

- University Hills

- Uptown

- Warehouse District

- Warren Sherman

- Westgate

- Westmoreland

According to the US Census Bureau, the Toledo Metropolitan Area covers four Ohio counties and one Michigan county, which combines with other micropolitan areas and counties for a combined statistical area. Some of what are now considered its suburbs in Ohio include: Bowling Green, Holland, Lake Township, Maumee, Millbury, Monclova Township, Northwood, Oregon, Ottawa Hills, Perrysburg, Rossford, Springfield Township, Sylvania, Walbridge, Waterville, Whitehouse, and Washington Township. Bedford Township, Michigan including the communities of Lambertville, Michigan, Temperance, Michigan, and Erie Township, Michigan are Toledo's Michigan suburbs, just above the city over the state line in Monroe County.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 1,222 | — | |

| 1850 | 3,829 | 213.3% | |

| 1860 | 13,768 | 259.6% | |

| 1870 | 31,584 | 129.4% | |

| 1880 | 50,137 | 58.7% | |

| 1890 | 81,434 | 62.4% | |

| 1900 | 131,822 | 61.9% | |

| 1910 | 168,497 | 27.8% | |

| 1920 | 243,164 | 44.3% | |

| 1930 | 290,718 | 19.6% | |

| 1940 | 282,349 | −2.9% | |

| 1950 | 303,616 | 7.5% | |

| 1960 | 318,003 | 4.7% | |

| 1970 | 383,818 | 20.7% | |

| 1980 | 354,635 | −7.6% | |

| 1990 | 332,943 | −6.1% | |

| 2000 | 313,619 | −5.8% | |

| 2010 | 287,208 | −8.4% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 272,779 | [4] | −5.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[37] | |||

| Racial composition | 2010[38] | 2000[39] | 1990[39] | 1970[39] | 1940[39] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 64.8% | 70.2% | 77.0% | 85.7% | 94.8% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 61.4% | Unk | 75.1% | 84.0%[40] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 27.2% | 23.5% | 19.7% | 13.8% | 5.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 7.4% | 5.5% | 4.0% | 1.9%[40] | n/a |

| Asian | 1.1% | 1.0% | 1.0% | 0.2% | − |

.png.webp)

As of the 2010 census, the city proper had a population of 287,128. It is the principal city in the Toledo Metropolitan Statistical Area which had a population of 651,429 and was the sixth-largest metropolitan area in the state of Ohio, behind Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, Dayton, and Akron.[41] The larger Toledo-Fremont Combined Statistical Area had a population of 712,373. According to the Toledo Metropolitan Council of Governments, the Toledo/Northwest Ohio region of 10 counties has over 1 million residents.

The U.S. Census Bureau estimated Toledo's population as 297,806 in 2006 and 295,029 in 2007. In response to an appeal by the City of Toledo, the Census Bureau's July 2007 estimate was revised to 316,851, slightly more than in 2000,[42] which would have been the city's first population gain in 40 years. However, the 2010 census figures released in March 2011 showed the population as of April 1, 2010, at 287,208, indicating a 25% loss of population since its zenith in 1970.

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 287,208 people, 119,730 households, and 68,364 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,559.4 inhabitants per square mile (1,374.3/km2). There were 138,039 housing units at an average density of 1,710.7 per square mile (660.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 64.8% White, 27.2% African American, 0.4% Native American, 1.1% Asian, 2.6% from other races, and 3.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 7.4% of the population (The majority are Mexican American at 5.1%.) Non-Hispanic Whites were 61.4% of the population in 2010,[43] down from 84% in 1970.[39]

There were 119,730 households, of which 30.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 31.6% were married couples living together, 19.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.7% had a male householder with no wife present, and 42.9% were non-families. 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.33 and the average family size was 3.01. There was a total of 139,871 housing units in the city, of which 10,946 (9.8%) were vacant.

The median age in the city was 34.2 years. 24% of residents were under the age of 18; 12.8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.3% were from 25 to 44; 24.8% were from 45 to 64; and 12.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.4% male and 51.6% female.

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 313,619 people, and 77,355 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,890.2 people per square mile (1,502.0/km2). There were 139,871 housing units at an average density of 1,734.9 per square mile (669.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 70.2% White, 23.5% African American, 0.3% Native American,1.0% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 2.3% from other races, and 2.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.5% of the population in 2000. The most common ancestries cited were German (23.4%), Irish (10.8%), Polish (10.1%), English (6.0%), American (3.9%), Italian (3.0%), Hungarian, (2.0%), Dutch (1.4%), and Arab (1.2%).[44]

In 2000 there were 128,925 households in Toledo, out of which 29.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.2% were married couples living together, 17.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.0% were non-families. 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 3.04.

In the city the population was spread out, with 26.2% under the age of 18, 11.0% from 18 to 24, 29.8% from 25 to 44, 19.8% from 45 to 64, and 13.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $32,546, and the median income for a family was $41,175. Males had a median income of $35,407 versus $25,023 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,388. About 14.2% of families and 17.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 25.9% of those under age 18 and 10.4% of those age 65 or over.

Crime

In 2018, the city was ranked 43rd of the Top 100 Most Dangerous Cities in America.[45]

In the second decade of the 21st century, the city had a gradual peak in violent crime. In 2010, there was a combined total of 3,272 burglaries, 511 robberies, 753 aggravated assaults, 25 homicides, as well as 574 motor vehicle thefts out of what was then a decreasing population of 287,208.[46] In 2011, there were 1,562 aggravated assaults, 30 homicides, 1,152 robberies, 8,366 burglaries, and 1,465 cases of motor vehicle theft. In 2012, there were a combined total of 39 murders, 2,015 aggravated assaults, 6,739 burglaries, and 1,334 cases of motor vehicle theft. In 2013 it had a drop in the crime rate.[47] According to a state government task force, Toledo has been identified as the fourth-largest recruitment site for human trafficking in the US.[48]

Economy

Before the industrial revolution, Toledo was important as a port city on the Great Lakes. With the advent of the automobile, the city became best known for industrial manufacturing. Both General Motors and Chrysler had factories in metropolitan Toledo, and automobile manufacturing has been important at least since Kirk started manufacturing automobiles,[49] which began operations early in the 20th century. The largest employer in Toledo was Jeep for much of the 20th century. Since the late 20th century, industrial restructuring reduced the number of these well-paying jobs.

The University of Toledo is influential in the city, contributing to the prominence of healthcare as the city's biggest employer. The metro area contains four Fortune 500 companies: Dana Holding Corporation, Owens Corning, The Andersons, and Owens Illinois. ProMedica is a Fortune 1000 company headquartered in Toledo. One SeaGate is the location of Fifth Third Bank's Northwest Ohio headquarters.

Glass industry

Toledo is known as the Glass City because of its long history of glass manufacturing, including windows, bottles, windshields, construction materials, and glass art, of which the Toledo Museum of Art has a large collection. Several large glass companies have their origins here. Owens-Illinois, Owens Corning, Libbey Incorporated, Pilkington North America (formerly Libbey-Owens-Ford), and Therma-Tru have long been a staple of Toledo's economy. Other offshoots and spinoffs of these companies also continue to play important roles in Toledo's economy. Fiberglass giant Johns Manville's two plants in the metro area were originally built by a subsidiary of Libbey-Owens-Ford.

Automotive industry

Several Fortune 500 automotive-related companies had their headquarters in Toledo, including Electric AutoLite, Sheller-Globe Corporation, Champion Spark Plug, Questor, and Dana Holding Corporation. Only the latter still operates as an independent entity.

Faurecia Exhaust Systems, a $2 billion subsidiary of France's Faurecia SA, is in Toledo.

Toledo is the Jeep headquarters and has two production facilities dubbed the Toledo Complex, one in the city and one in suburban Perrysburg. During World War II, the city's industries produced important products for the military, particularly the Willys Jeep.[50] Willys-Overland was a major automaker headquartered in Toledo until 1953.

Industrial restructuring and loss of jobs caused the city to adopt new strategies to retain its industrial companies. It offered tax incentives to DaimlerChrysler to expand its Jeep plant. In 2001, a taxpayer lawsuit was filed against Toledo that challenged the constitutionality of that action. In 2006, the city won the case by a unanimous ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in DaimlerChrysler Corp. v. Cuno.

General Motors also has operated a transmission plant in Toledo since 1916. It manufactures and assembles GM's six-speed and eight-speed rear-wheel-drive and six-speed front-wheel-drive transmissions that are used in a variety of GM vehicles.[51]

Green industry

Belying its Rust Belt history, the city saw growth in "green jobs" related to solar energy in the 2000s.[52] The University of Toledo and Bowling Green State University received Ohio grants for solar energy research.[53] Xunlight and First Solar opened plants in Toledo and the surrounding area.[54] In May 2019 Balance Farms began operation of a 8,168 square foot indoor aquaponics farm in downtown Toledo.[55]

Arts and culture

Fine and performing arts

Toledo is home to a range of classical performing arts institutions, including The Toledo Opera, The Toledo Symphony Orchestra, the Toledo Jazz Orchestra and the Toledo Ballet. The city is also home to several theaters and performing arts institutions, including the Stranahan Theater, the historic Valentine Theatre, the Toledo Repertoire Theatre, the Collingwood Arts Center and the Ohio Theatre.

The Toledo Museum of Art is located in a Greek Revival building in the city's Old West End neighborhood. The Peristyle is the concert hall in Greek Revival style in its East Wing; it is the home of the Toledo Symphony Orchestra, and hosts many international orchestras as well. The Museum's Center for Visual Arts addition was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in the 21st century. In addition, the museum's new Glass Pavilion across Monroe Street opened in August 2006. Toledo was the first city in Ohio to adopt a One Percent for Art program and, as such, boasts many examples of public, outdoor art.[56] A number of walking tours have been set up to explore these works, which include large sculptures, environmental structures, and murals by more than 40 artists, such as Alice Adams, Pierre Clerk, Dale Eldred, Penelope Jencks, Hans Van De Bovenkamp, Jerry Peart, and Athena Tacha.[57]

Music

Toledo has a rich history of music, dating back to their early to mid-20th century glory days as a jazz haven. During this time, Toledo produced or nurtured such jazz legends as Art Tatum, Jon Hendricks, trombonist Jimmy Harrison, pianist Claude Black, guitarist Arv Garrison, pianist Johnny O’Neal, and many, many others.[58] Later jazz greats from Toledo include Stanley Cowell, Larry Fuller, Bern Nix and Jean Holden.

Other well-known singers and musicians with Toledo roots include Teresa Brewer, Tom Scholz, Anita Baker, Shirley Murdock, American Idol runner-up Crystal Bowersox, The Rance Allen Group, Lyfe Jennings and Weezer bassist Scott Shriner.[59] Rance Allen Died at age of 71. Oct 31,2020

In popular culture

The hit television show M*A*S*H featured actor and Toledo native Jamie Farr as Corporal Maxwell Klinger, also a Toledo native who shared many local references in the show, making the minor-league Toledo Mud Hens baseball team and hot dog eatery Tony Packo's Cafe famous around the world.

The Kenny Rogers 1977 hit song "Lucille" was written by Hal Bynum and inspired by his trip to Toledo in 1975.[60]

Toledo is mentioned in the song "Our Song" by Yes from their 1983 album 90125. According to Yes drummer Alan White, Toledo was especially memorable for a sweltering-hot 1977 show the group did at Toledo Sports Arena.[61]

The season 1 episode of the Warner Bros television series Supernatural titled "Bloody Mary" was set in Toledo.[62]

The popular phrase "Holy Toledo," is thought to originally be a reference to the city's array of grand church designs from Gothic, Renaissance and Spanish Mission. There are many other theories as well.[63][64]

Toledo is the setting for the 2010 television comedy Melissa & Joey, with the first-named character being a city councilwoman.[65]

Other movies and TV shows set in a fictionalized version of Toledo include A.P. Bio, Feed and Kiss Toledo Goodbye. The Tony Curtis vehicle, Johnny Dark was primarily shot in Toledo.

John Denver recorded "Saturday Night In Toledo, Ohio," composed by Randy Sparks. He wrote it in 1967 after arriving in Toledo with his group and finding no nightlife at 10 p.m.[66] After Denver performed the song on The Tonight Show, Toledo residents objected. In response, the City Fathers recorded a song entitled "We're Strong For Toledo". Ultimately the controversy was such that John Denver cancelled a concert in Toledo shortly thereafter. But when he returned for a 1980 concert, he set a one-show attendance record at the venue, Centennial Hall, and sang the song to the approval of the crowd.[67]

Sports

- Auto Racing – Toledo Speedway is a local auto racetrack that features, among other events, stock car racing and concerts. The Automobile Racing Club of America (ARCA) has its headquarters in Toledo.

- Baseball – The Toledo Mud Hens are one of Minor League Baseball's oldest teams, having first played in 1896. They play at Fifth Third Field which was completed in 2002. They have won one American Association title and three International League titles. The Mud Hens are the Triple-A affiliate of the MLB Detroit Tigers.

- Boxing - Jack Dempsey won the world heavyweight boxing championship from Jess Willard on July 4, 1919.

- Golf – Inverness Club is a golf club in Toledo. It is known for hosting six major USGA events, most recently the 1993 PGA Championship. The U.S. Senior Open took place there in 2003 and 2011. Highland Meadows Golf Club has been home to the LPGA's Marathon Classic in the nearby suburb of Sylvania since 1984 (yearly except for 1986 and 2011).

- Hockey – The Toledo Walleye are an ECHL hockey team that began play at the Huntington Center in 2009. The Walleye are an affiliate of the Grand Rapids Griffins of the American Hockey League, and the Detroit Red Wings of the NHL. Toledo has a rich history of pro hockey, which includes 11 championships between four teams in the International Hockey League and ECHL.

- Football – The Toledo Reign are a women's full-contact tackle football team in the Women's Football Alliance. Established in 2003, the Reign plays regular season games from April through June. The Toledo Crush of the Legends Football League played at the Huntington Center in 2014 after relocating from Cleveland, where it played from 2011 to 2013.[68] The Toledo Maroons played in the Ohio League from 1902 until 1921 and the NFL from 1922 until 1923 before moving to Kenosha, Wisconsin.[69]

- Roller Derby – The Glass City Rollers is a full member of the Women's Flat Track Derby Association. The league was formed in 2007 and became a full member of the WFTDA in 2012. Their bouts are held at the International Boxing Club in the suburb of Oregon.

- Soccer - Founded in 2017, Toledo Villa FC is a semi-professional soccer team located in Toledo, OH. The team plays out of the National Premier Soccer League (NPSL). The club is committed to its vision to place the best product on the pitch, develop players that are committed to upholding the traditions of the game, inspire young athletes for the future of the game and provide a model business that positively impacts the community.

- Wrestling – Toledo could be proudly called a "Wrestling Capital of the World," as the city hosted the International Federation of Associated Wrestling Styles (FILA) Congress in 1966, two editions of World Championships (both freestyle and Greco-Roman), seventeen editions of Freestyle Wrestling World Cup, and numerous high-profile international duals were held at the Toledo Field House and Centennial Hall.

Parks and recreation

- The Toledo Zoo was the first zoo to feature a hippoquarium-style exhibit. In 2014 it was ranked as the #1 zoo in the country by USA Today.[70]

- The National Museum of the Great Lakes (NMGL) is located in the Marina District, downstream from downtown Toledo.[71]

- Adjacent to the NMGL, the Col. James M. Schoonmaker is a former Cleveland-Cliffs lake freighter open to the public as a museum. Moored in the Maumee River, the ship was recently repainted in the original Shenango Furnace fleet colors and, on 1 July 2011, rechristened with her original name.[71]

- The R. A. Stranahan Arboretum is a 47-acre (190,000 m2) arboretum maintained by the University of Toledo.[72]

- Tony Packo's Cafe is located in the Hungarian neighborhood on the east side of Toledo known as Birmingham; it features hundreds of hot dog buns signed by celebrities.[73]

- The Toledo Metroparks system includes over 12,000 acres (49 km2) of land, and features the University/Parks Bicycle Trail and the Toledo Botanical Garden.[74]

- On January 15, 1936, the first building to be completely covered in glass was constructed in Toledo. It was a building for the Owens-Illinois Glass Company and marked a milestone in architectural design representative of the International style of architecture, which was at that time becoming increasingly popular in the US.

- The Imagination Station hands-on science museum (formerly COSI Toledo), is located downtown.

- The Toledo Lucas County Public Library was 4-star rated for 2009 by the Library Journal, and it is sixth among the biggest-spending libraries in the United States.[75]

- Toledo has the University Bike and Walking Trail, which is 6.3 miles (10.1 km). This trail goes northwest from The University of Toledo to Sylvania, Ohio.[76]

- Hollywood Casino Toledo opened on May 29, 2012.

Education

Colleges and universities

These higher education institutions operate campuses in Toledo:

- The University of Toledo[77]

- University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences[77]

- Davis College[77]

- Mercy College of Ohio[77]

- Owens Community College (Perrysburg Township)

- Toledo Academy of Beauty

- Toledo Professional Skills Institute[77]

- Tiffin University (Toledo Campus)

- Toledo Career Institute

Primary and secondary schools

Toledo Public Schools operates public schools within much of the city limits, along with the Washington Local School District in northern Toledo. Toledo is also home to several public charter schools including two Imagine Schools. Additionally, several private and parochial primary and secondary schools are present within the Toledo area. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Toledo operates Roman Catholic primary and secondary schools in 19 counties in Northwest Ohio, including Lucas County and the Toledo area.[78] Notable private high schools in Toledo include:

- Maumee Valley Country Day School[79]

- Central Catholic High School[80]

- St. Francis de Sales High School[81]

- St. John's Jesuit High School and Academy[82]

- Notre Dame Academy[83]

- St. Ursula Academy (Ottawa Hills)[84]

- Cardinal Stritch Catholic High School (Oregon)[85]

- Toledo Christian Schools[86]

- Emmanuel Christian School[87]

Media

The eleven-county Northwest Ohio/Toledo/Fremont media market includes over 1 million residents. The Blade, a daily newspaper founded in 1835, is the primary newspaper in Toledo. The front page claims that it is "One of America's Great Newspapers." The city's arts and entertainment weekly is the Toledo City Paper. From March 2005 to 2015, the weekly newspaper Toledo Free Press was published, and it had a focus on news and sports. Other weeklies include the West Toledo Herald, El Tiempo, La Prensa, Sojourner's Truth, and Toledo Journal. Toledo Tales provides satire and parody of life in the Glass City. The Toledo Journal is an African-American owned newspaper. It is published weekly, and normally focuses on African-American issues.

Eight television stations are in Toledo. They are: 11 WTOL – CBS, 13 WTVG – ABC, 13.2 - WTVG - CW, 24 WNWO-TV – NBC, 30 WGTE-TV – PBS, 36 WUPW – Fox, 38 W38DH – HSN, 40 WLMB – The Cowboy Channel and 48 (Over-the-air Only) and 58 (Cable Only, per the "My 58" moniker) WMNT-CD – Infomercials. 27 WBGU – PBS in Bowling Green is also viewable. Toledoans can also watch the adjacent Detroit and Ann Arbor market stations, both over-the air and on cable. There are also fourteen radio stations licensed in Toledo.

Infrastructure

Major highways

Three major interstate highways run through Toledo. Interstate 75 (I-75) travels north–south and provides a direct route to Detroit and Cincinnati. The Ohio Turnpike carries east–west traffic on I-80/90. The Turnpike serves Toledo via exits 52, 59, 64, 71, and 81. The Turnpike connects Toledo to Chicago in the west and Cleveland in the east.

In addition, there are two auxiliary interstate highways in the area. Interstate 475 is a 20-mile bypass that begins in Perrysburg and ends in west Toledo, meeting I-75 at both ends. It is cosigned with US 23 for its first 13 miles. Interstate 280 is a spur that connects the Ohio Turnpike to I-75 through east and central Toledo. The Veterans' Glass City Skyway is part of this route, which was the most expensive ODOT project ever at its completion. This 400-foot (120 m) tall bridge includes a glass covered pylon, which lights up at night, adding a distinctive feature to Toledo's skyline.[88] The Anthony Wayne Bridge, a 3,215-foot (980 m) suspension bridge crossing the Maumee River, has been a staple of Toledo's skyline for more than 80 years. It is locally known as the "High-Level Bridge."

Mass transit

Local bus service is provided by the Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority; commonly shortened to TARTA. Toledo area Paratransit Services; TARPS are used for the disabled. Intercity bus service is provided by Greyhound Lines whose station is located at Martin Luther King, Jr. Plaza which it shares with Amtrak. Megabus also provides daily trips to Ann Arbor, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and Pittsburgh. Toledo has various cab companies within its city limits and other ones that surround the metro.

Airports

Toledo Express Airport, located in the suburbs of Monclova and Swanton Townships, is the primary airport that serves the city. Additionally, Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport is 45 miles north. Toledo Executive Airport (formerly Metcalf Field) is a general aviation airport southeast of Toledo near the I-280 and Ohio SR 795 interchange. Toledo Suburban Airport is another general aviation airport located in Lambertville, MI just north of the state border.

Railroads at present

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service to Toledo and other major cities under the Capitol Limited and the Lake Shore Limited. Both lines stop at Martin Luther King, Jr. Plaza, which was built as Central Union Terminal by the New York Central Railroad—along its Water Level Route—in 1950. Of the seven Ohio stations served by Amtrak, Toledo was the busiest in fiscal year 2011, boarding or detraining 66,413 passengers.[89] Freight rail service presently in Toledo is operated by the Norfolk Southern Railway, CSX Transportation, Canadian National Railway, Ann Arbor Railroad, and Wheeling and Lake Erie Railway. All except the Wheeling have local terminals; the Wheeling operates into Toledo from the east through trackage rights on Norfolk Southern to connect with the Ann Arbor and CN railroads.

Railroads in the past

Historically, Toledo was a major rail hub where the New York Central (later, the Penn Central), Baltimore and Ohio, Wabash Railroad, Nickel Plate Road, Ann Arbor Railroad, Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad, Toledo, Peoria and Western Railway, Pennsylvania Railroad, Chesapeake and Ohio Railway/Pere Marquette Railway, Wheeling and Lake Erie railroads moved a large amount of freight to and from Toledo's many industries such as Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass, and Willys-Overland (Jeep) Motors. Most of these companies used Central Union Terminal on Emerald Avenue. The Ann Arbor Railroad used its station on Cherry Street. The Pennsylvania Railroad used its station on Summit Street.[90][91][92]

Interurbans

Toledo had a streetcar system and interurban railways[93] linking it to other nearby towns but these are no longer in existence. Seven interurban companies radiated from Toledo. In the early 1930s, three of the seven, the Cincinnati and Lake Erie from Cincinnati, Columbus, Dayton, and Springfield, the Lake Shore Electric from Cleveland, and the Eastern Michigan Ry from Detroit, moved a large amount of freight and passengers between those heavily industrialized cities. The Great Depression and growing inter city competition from trucks on newly improved roads by the Ohio caused abandonment of all by 1938, and some interurban lines much earlier.[94] The interurban station where all lines met and exchanged passengers was on N. Summit Street. Freight was exchanged in a rail yard with a warehouse off Lucas Street.[95]

Healthcare

Originating in Toledo, ProMedica is an integrated healthcare organization founded in 2009. It has grown rapidly to become the country's 15th largest non-profit health care system in the United States, with 2018 revenues of $7 billion.[96] It is headquartered on Madison Avenue in Downtown Toledo and maintains 13 hospitals in Northwest Ohio and Southeast Michigan, including ProMedica Toledo Hospital, the largest acute care hospital in the area.[97]

Mercy Health - St. Vincent Medical Center, Toledo's first hospital and part of Mercy Health Partners, holds the highest designation for treating high-risk mothers and babies, is a Level I Trauma Center for children and adults, and is an accredited Chest Pain Center.[98] It is located in the Vistula Historic District on the city's north side.

There are also 18 community health centers in Toledo.[99] Some examples include the Cordelia Martin Community Health Center, the East Toledo Community Health Center, and the Monroe Street Neighborhood Center.

Water

The Division of Water Treatment filters an average of 80 million gallons of water per day for 500,000 people in the greater Toledo Metropolitan area.[100] The Division of Water Distribution serves 136,000 metered accounts and 10,000 fire hydrants and maintains more than 1,100 miles (1,800 km) of water mains.[101]

In August 2014, two samples from a water treatment plant toxin test showed signs of microcystis. Roughly 400,000, including residents of Toledo and several surrounding communities in Ohio and Michigan were affected by the water contamination. Residents were told not to use, drink, cook with, or boil any tap water on the evening of August 1, 2014.[102] The Ohio National Guard delivered water and food to residents living in contaminated areas. As of August 3, 2014, no one had reported being sick and the governor had declared a state of emergency in three counties.[103][104] The ban was lifted on August 4.[105]

Notable people

Sister cities

Toledo was twinned with Toledo, Spain, in 1931, creating the first sister city relationship in the United States.[106][107]

Toledo's sister cities are:[108][109]

Beqaa Valley, Lebanon

Beqaa Valley, Lebanon Coburg, Germany

Coburg, Germany Coimbatore, India

Coimbatore, India Delmenhorst, Germany

Delmenhorst, Germany Hyderabad, Pakistan

Hyderabad, Pakistan Londrina, Brazil

Londrina, Brazil Nanchong, China

Nanchong, China Poznań, Poland

Poznań, Poland Qinhuangdao, China

Qinhuangdao, China Szeged, Hungary

Szeged, Hungary Tanga, Tanzania

Tanga, Tanzania Toledo, Spain

Toledo, Spain Toyohashi, Japan

Toyohashi, Japan

See also

- Auto-Lite strike

- Baseball parks of Toledo, Ohio

- Glassmen Drum and Bugle Corps, Drum Corps International World Class Drum and Bugle Corps

- Greater Toledo

- Outbreak of green-blue algae in Lake Erie

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Toledo

- Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority, local bus transportation

- Toledo City League, high school sports league

Notes

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- Official records for Toledo were kept at downtown from January 1871 to January 1943, Toledo Municipal Airport from February 1943 to December 1945, Metcalf Field from January 1946 to 11 January 1955, and at Toledo Express Airport since 12 January 1955. For more information, see ThreadEx.

References

- "laborare est orare". Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Zip Code Lookup". USPS. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Toledo's population continues to decline, according to census estimate". Toledo Blade. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- "Port Industry Statistics". www.aapa-ports.org. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History (University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1986) pp. 3, 58–59

- R. Douglas Hurt, The Ohio Frontier: Crucible of the Old Northwest, 1720–1830 (Indiana University Press: Bloomington, 1998), pp. 8–12

- Charles E. Slocum, "Forts Miami and Fort Industry", Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications, Volume XII, 1903; hosted at American History and Genealogy Project, accessed 26 December 2015

- "Treaty Between the Ottawa, Chippewa, Wyandot, and Potawatomi Indians". World Digital Library. November 17, 1807. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- Federal Writers' Project (1940). The Ohio Guide. US History Publishers. ISBN 9781603540346.

- Gieck, Jack (1988). A Photo Album of Ohio's Canal Era, 1825–1913. Kent: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873383530.

- Hodge, Frederick Webb (1910). "Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico: N-Z". Books.google.com. p. 167. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- Helen Hornbeck Tanner, ed., Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History (University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1986) pp. 48-51

- Larry Angelo (2nd chief of the Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma), The Migration of the Ottawas from 1615 to Present, (1997), pp. 3-6

- Tanber, George J. (December 24, 2000). "Benjamin Franklin Stickney: His remarkable life and times". The Blade. Archived from the original on November 16, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- Mitchell, Gordon (June 2004). "History Corner: Ohio-Michigan Boundary War, Part 2". Professional Surveyor Magazine. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- Simonis, Louis A. (1979). Maumee River, 1835. Defiance: Defiance County Historical Society.

- Messer-Kruse, Timothy. "Toledo Topics: Life at the Top in Jazz Age Toledo". Toledo's Attic. Toledo. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "Downtown Toledo: What went wrong?". Toledo Blade.

- Wessner, Charles (2013). "Rebuilding Ohio's Innovation Economy". National Academies Press (US). Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- "Cleveland Cliffs invests $700 million in Toledo". wtol.com.

- "The State of Urban Agriculture | Toledo City Paper". toledocitypaper.com.

- "Hitting the wall: Vibrant murals continue to proliferate in Toledo". Toledo Blade.

- "Lofts a fit downtown". Toledo Blade.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- "History of the Oak Openings Region". Green Ribbon Initiative. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- "WMO Climate Normals for TOLEDO/EXPRESS, OH 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- "Station Name: OH TOLEDO EXPRESS AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- "Thread Stations Extremes". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- "Toledo, OH - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- "State & County QuickFacts: Toledo (city), Ohio". U.S. Census Bureau. July 8, 2014. Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- "Ohio - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- From 15% sample

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Toledo, OH Metro Area". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- "Thousands added to Toledo census count". The Blade. Toledo. January 14, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- "State & County QuickFacts: Toledo (city), Ohio". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- "QT-P13. Ancestry: 2000 - Toledo city, Ohio". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- "Top 100 most dangerous places to live in the U.S. in 2018". January 2, 2018. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- "FBI — Table 4 Montana - Ohio". FBI.

- "Toledo's crime rate takes plunge". Toledo Blade.

- "Ohio Human Trafficking Task Force: Recommendations to Governor John R. Kasich" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 14, 2016.

- Clymer, Floyd (1950). Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 158.

- "Toledo, Ohio". Ohio History Central. July 1, 2005. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "Toledo Transmission". media.gm.com. GM. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- "Cities on the Front Lines". The American Prospect. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- Ramsey, Duane (July 30, 2009). "State awards solar research grant to UT, BGSU". Toledo Free Press. Toledo. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- Swicord, Jeff (July 28, 2009). "Old US Industrial Town Looking Forward to a Green Future". Voice of America. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009.

- "A look inside Balance Farms, downtown Toledo's aquaponics operation". Toledo Blade. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- Lane, Tahree; Smith, Ryan E. (January 20, 2008). "Public art effort expands as Toledo program takes on change in 30th year". The Blade. Toledo. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "Toledo Sculpture Tours" (PDF). Arts Commission of Greater Toledo. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "'Tatum's Town' highlights Toledo's long love affair with music". Toledo Blade.

- "Artists and bands from Toledo, OH". AllMusic.

- Reindl, J. C. (March 22, 2010). "Music fades, curtain closes on once-hot Toledo night spot". The Blade. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- Kisiel, Ralph (March 1, 1984). "Sweltering Night Keeps City Fresh in the Memory of Yes". The Blade. p. 2. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- "Supernatural: "Bloody Mary" Review - IGN". Au.ign.com. April 18, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- "Holy Toledo". Toledo.com.

- "'Holy Toledo' is still thriving". Toledo Blade.

- Baird, Kirk (August 26, 2010). "TV series 'Melissa & Joey' is set in Toledo, but city lacks starring role". The Blade. Toledo. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- Barhite, Brandi (December 26, 2008). "'Saturday Night In Toledo' author changes his tune". Toledo Free Press. Toledo. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "Saturday Night in Toledo, Ohio". Toledo History Box. August 9, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- Kent, Julie (December 17, 2013). "Cleveland Losing its Lingerie Sporting Football Team the Crush to Toledo". The Cleveland Leader. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- Toledo Maroons Franchise Encyclopedia

- "Best US Zoo Winners: 2014 10Best Readers' Choice Travel Awards". 10Best.

- "The Great Lakes Historical Society: Museum". The Great Lakes Historical Society. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- "Stranahan Arboretum". The University of Toledo. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- "History of Tony Packo's: The Real Story". Tony Packo's. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "A Rich History". Metroparks Toledo. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- Curry Lance, Keith; Lyons, Ray (November 15, 2009). "America's Star Libraries: Who's In, Who's Out". Library Journal. New York. Archived from the original on April 20, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "University/Parks Trail". Metroparks of the Toledo Area. Archived from the original on June 3, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "Colleges and Universities in Toledo, Ohio". MyCollegeOptions.org. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- "The Catholic Diocese of Toledo: Catholic Schools". toledodiocese.org. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "History of Maumee Valley Country Day School". December 8, 2016. Archived from the original on December 8, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "History, Fight Song, & Alma Mater - Central Catholic High School". July 9, 2016. Archived from the original on July 9, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "St. Francis de Sales School: About Us". March 8, 2018. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "About Us - St. John's Jesuit". August 31, 2018. Archived from the original on August 31, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "Who We Are – NDA". April 2, 2018. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "Fast Facts - St. Ursula Academy". October 28, 2018. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "History | Cardinal Stritch". October 28, 2018. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "History and Governance | Toledo Christian Schools". June 17, 2017. Archived from the original on June 17, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "Emmanuel Christian School: A History of Christian Education". December 19, 2017. Archived from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "Ohio DOT endorses design for Maumee River crossing". Civil Engineering. 70 (9): 12. September 2000. Retrieved August 4, 2014 – via Transportation Research Board.

- "Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2011: State of Ohio" (PDF). Amtrak. December 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- Railroad maps of the 1930s-40s; and Toledo Municipal corporation records.

- The Great Union Stations, "Toledo's Passenger Trains" https://www.chicagorailfan.com/stbctol.html

- "Index of Railroad Stations, 1468". Official Guide of the Railways. National Railway Publication Company. 87 (7). December 1954.

- Patch, David (May 27, 2007). "Toledo was hub of interurban 100 years ago". The Blade. Toledo. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- The Cincinnati and Lake Erie Railroad, Keenan, Jack: Golden West Books, San Marino, CA, 1974. ISBN 0-87095-055-X: p77-79.

- Keenan, p 155, inc. Lucas rail yard photo.

- "ProMedica to acquire HCR ManorCare". Modern Healthcare. April 26, 2018.

- "Locations | ProMedica". www.promedica.org.

- "St. Vincent Medical Center". www.mercy.com.

- "Free and Income Based Clinics Toledo OH". www.freeclinics.com.

- "Division of Water Treatment". City of Toledo. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "Division of Water Distribution". City of Toledo. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- Henry, Tom (August 3, 2014). "Water crisis grips hundreds of thousands in Toledo area, state of emergency declared". The Blade. Toledo. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- Capelouto, Susanna; Morgenstein, Mark (August 3, 2014). "400,000 in Toledo, Ohio, water scare await test results". CNN. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- Queally, James (August 2, 2014). "Toxic Ohio tap water tested as 500,000 residents wait". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- Karimi, Faith; Morgenstein, Mark (August 4, 2014). "'Our water is safe,' Toledo mayor says in lifting ban". CNN. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "Oldest Sister City Relationship Established Between Toledo, Ohio and Toledo, Spain". Sister Cities International (SCI). January 30, 1931. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- Hendel, Barbara (October 7, 2018). "Toledo Sister Cities marks 25 years". Toledo Blade. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- "Welcome". Toledo Sister Cities International. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- "Londrina, Brazil". Toledo Sister Cities International. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

Further reading

- Bloom, Matthew (Spring 2010). "Symbiotic Growth in the Swamp: Toledo and Northwest Ohio, 1860–1900". Northwest Ohio History. 77 (2): 85–104.

External links

- Official website

- Greater Toledo Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Toledo, Ohio, 1876 from the World Digital Library

- About Toledo, Ohio (via Britannica)

.svg.png.webp)