Arenysuchus

Arenysuchus (meaning "Arén crocodile") is an extinct genus of crocodyloid from Late Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian stage) deposits of north Spain. It is known from the holotype MPZ ELI-1, a partial skull from Elías site, and from the referred material MPZ2010/948, MPZ2010/949, MPZ2010/950 and MPZ2010/951, four teeth from Blasi 2 site. It was found by the researchers José Manuel Gasca and Ainara Badiola from the Tremp Formation, in Arén of Huesca, Spain. It was first named by Eduardo Puértolas, José I. Canudo and Penélope Cruzado-Caballero in 2011 and the type species is Arenysuchus gascabadiolorum. The generic name refers to the finding site, and "suchus", from Greek meaning crocodile. The specific name honours the researchers who discovered the holotype.

| Arenysuchus | |

|---|---|

| |

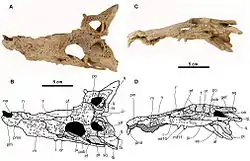

| Skull (ELI-1) and diagram | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Eusuchia |

| Family: | †Allodaposuchidae |

| Genus: | †Arenysuchus Puértolas, Canudo & Cruzado-Caballero, 2011 |

| Type species | |

| †Arenysuchus gascabadiolorum Puértolas, Canudo & Cruzado-Caballero, 2011 | |

Etymology

Arenysuchus was named and described in 2011 by Eduardo Puértolas and his colleagues for a partial skull and teeth. For the generic name, Areny is named after Arén, spelt as Areny in the Catalan language, the locality where the skull was found, and souchus, the Greek word for crocodile, leading to Latin, suchus. The specific epithet of "gascabadiolorum" is dedicated to the researchers José Manuel Gasca and Ainara Badiola, who discovered the holotype.[1]

Description

Arenysuchus is known a partial skull and four teeth. One feature linking it to early crocodilians is the contact of the frontal bones with the margin of the supratemporal fenestrae, two holes in the top of the skull. The frontal bone is also unusual in that its front end is extremely long. A sharp projection of the frontal divides the nasal bones, making up most of the midline length of the snout. Usually, the nasal bones would occupy the midline and the frontal would be restricted near the eye sockets. Near the frontal, the lacrimal bones are unusually wide in comparison to their length. Below the supratemporal fenestrae are the Infratemporal fenestra, long openings along the side of the skull behind the eyes. The infratemporal bar (a projection of the jugal bone below the infratemporal fenestra) is very thin and vertically expanded. In most other crocodilians, it is thicker and laterally, not vertically, expanded. The edges of the orbits, or eye sockets, are raised. The orbit edges of more advanced crocodyloids like modern crocodiles are also raised, but those of the closest relatives of Arenysuchus are not. Another feature of Arenysuchus that distinguishes it from other basal crocodyloids is its small palatine process, a bony plate of the maxilla that forms the front portion of the palate. The palatine process of basal crocodyloids usually extends to the suborbital fenestrae, a pair of holes on the underside of the skull beneath the orbits. In Arenysuchus, the process is much shorter. Arenysuchus also has a pit between the seventh and eighth maxillary teeth that is otherwise only seen in "Crocodylus" affinis. This pit would hold a dentary tooth if the lower jaw were present. All other teeth of the lower jaw are set inward from those of the upper jaw, so they are covered by the upper teeth when the jaws are closed.[1]

Distinguishing anatomical features

Arenysuchus can be distinguished by the following features: an infratemporal bar that is tabular and vertically oriented, with little dorsoventral thickness and an extreme lateromedial compression; the dorsal portion of the anterior process of the frontal bone has a very elongated and lanceolate morphology; the anterior process of the frontal projects strongly beyond the main body of the frontal and extends between the nasals, ending in a sharp point beyond the anterior margin of the orbits and the prefrontal bone, at the height of the anterior end of the lacrimal bone.[1]

Phylogeny

In Puértolas, Canudo & Cruzado-Caballero's phylogenetic analysis, Arenysuchus was found to be one of the most basal members of Crocodyloidea, the superfamily of crocodilians that includes crocodiles and their extinct relatives. Other basal crocodyloids include Prodiplocynodon and "Crocodylus" affinis from North America and Asiatosuchus from Europe. Of these genera, only Arenysuchus and Prodiplocynodon are known from the Late Cretaceous, making them the earliest known crocodyloids. Below is a cladogram after Puértolas, Canudo & Cruzado-Caballero, 2011:[1]

| Crocodylia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Arenysuchus was part of an initial evolutionary radiation of crocodylians in the Northern Hemisphere during the Late Cretaceous. During the late Maastrichtian, Europe was an island archipelago surrounded by shallow seas. In this archipelago, crocodilians made up the majority of the crocodylomorph fauna. In the southern hemisphere, however, crocodilians were not yet common, with other crocodylomorphs like metasuchians comprising the dominant fauna. Crocodilians were entirely absent from Europe before this time. Dinosaurs were abundant, with a diversity of sauropods, theropods, and ornithopods. With the formation of the archipelago, a faunal turnover took place in the late Maastrichtian. Dinosaurs became much rarer, primarily represented by hadrosaurs. Crocodylians radiated to become a much larger component of the island ecosystems.[1]

With the exception of Prodiplocynodon, Late Cretaceous North American crocodylians were mostly alligatoroids and gavialoids. In what is known as vicariance, migration did not occur between Europe and North America, separating the two crocodilian faunas. It was not until the Paleocene that crocodyloids diversified into the more derived relatives of Arenysuchus.[1]

Paleoecology

The Elias site, located west of Arén, is on the west end of the Tremp Syncline. Geographically, the site is located in Unit 2 of the Tremp Formation, and equivalent of the Conques Formation. In the same section of the Tremp Formation, but lower down, are the Blasi sites 1-3. The dinosaurs Arenysaurus and Blasisaurus are both from Blasi 1-3. The Tremp Formation is made up of 900 m (3,000 ft) of reddish rock in the South Pyrenean central Unit. Lower in the formation is a mix of platform marine deposits, that are late Campanian to Maastrichtian in age. Blasi 1 is located in the upper Arén Formation, with Blasi 3 extending into the upper Tremp Formation.[1]

The Tremp Formation dates to the late Cretaceous. It has been dated by means of planktonic foraminifers and magnetostratigraphy. The formation includes the planktonic Abathomphalus mayaroensis Biozone, which was dated in 2011 from 68.4 to 65.5 Ma. This gives the formation a late Campanian to early Danian age. The bottom of the Elias site is about 67 million years old, so the site dates from 67.6 to 65.5 Ma.[1]

References

- Puértolas, E.; Canudo, J.I.; Cruzado-Caballero, P. (2011). Farke, Andrew A. (ed.). "A New Crocodylian from the Late Maastrichtian of Spain: Implications for the Initial Radiation of Crocodyloids". PLoS ONE. 6 (6): e20011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020011. PMC 3110596. PMID 21687705.