Avestan

Avestan /əˈvɛstən/,[1] also known historically as Zend, comprises two languages: Old Avestan (spoken in the 2nd millennium BCE) and Younger Avestan (spoken in the 1st millennium BCE). The languages are known only from their use as the language of Zoroastrian scripture (the Avesta), from which they derive their name. Both are early Iranian languages, a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages within the Indo-European family. Its immediate ancestor was the Proto-Iranian language, a sister language to the Proto-Indo-Aryan language, with both having developed from the earlier Proto-Indo-Iranian. As such, Old Avestan is quite close in grammar and lexicon to Vedic Sanskrit, the oldest preserved Indo-Aryan language.

| Avestan | |

|---|---|

| 𐬎𐬞𐬀𐬯𐬙𐬀𐬎𐬎𐬀𐬐𐬀𐬉𐬥𐬀 | |

| Region | Eastern Iranian Plateau |

| Era | Iron Age, Late Bronze Age |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ae |

| ISO 639-2 | ave |

| ISO 639-3 | ave |

| Glottolog | aves1237 |

| Linguasphere | 58-ABA-a |

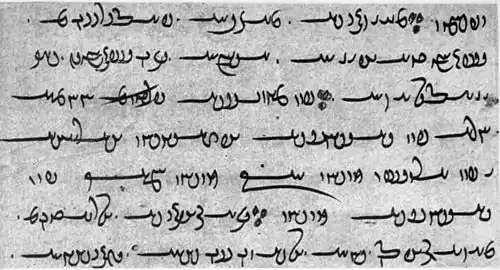

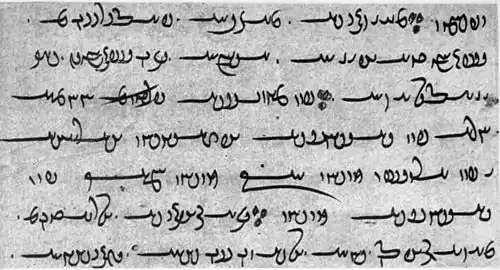

Yasna 28.1, Ahunavaiti Gatha (Bodleian MS J2) | |

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Avestan text corpus was composed in ancient Arachosia, Aria, Bactria, and Margiana,[2] corresponding to the entirety of present-day Afghanistan, and parts of Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The Yaz culture[3] of Bactria-Margiana has been regarded as a likely archaeological reflection of the early "Eastern Iranian" culture described in the Avesta.

Genealogy

"Avestan, which is associated with northeastern Iran, and Old Persian, which belongs to the southwest, together constitute what is called Old Iranian."[4][f 1] Scholars traditionally classify Iranian languages as "old", "middle" and "new" according to their age, and as "eastern" or "western" according to geography, and within this framework Avestan is classified as Eastern Old Iranian. But the east–west distinction is of limited meaning for Avestan, as the linguistic developments that later distinguish Eastern from Western Iranian had not yet occurred. Avestan does not display some typical (South-)Western Iranian innovations already visible in Old Persian, and so in this sense, "eastern" only means "non-western".[6]

Old Avestan is closely related to Old Persian and largely agrees morphologically with Vedic Sanskrit.[7] The old ancestor dialect of Pashto was close to the language of the Gathas.[8]

Forms and stages of development

The Avestan language is attested in roughly two forms, known as "Old Avestan" (or "Gathic Avestan") and "Younger Avestan". Younger Avestan did not evolve from Old Avestan; the two differ not only in time, but are also different dialects. Every Avestan text, regardless of whether originally composed in Old or Younger Avestan, underwent several transformations. Karl Hoffmann traced the following stages for Avestan as found in the extant texts. In roughly chronological order:

- The natural language of the composers of the Gathas, the Yasna Haptanghaiti, the four sacred prayers (Y. 27 and 54).

- Changes precipitated by slow chanting

- Changes to Old Avestan due to transmission by native speakers of Younger Avestan

- The natural language of the scribes who wrote grammatically correct Younger Avestan texts

- Deliberate changes introduced through "standardization"

- Changes introduced by transfer to regions where Avestan was not spoken

- Adaptions/translations of portions of texts from other regions

- Composition of ungrammatical late Avestan texts

- Phonetic notation of the Avestan texts in the Sasanian archetype

- Post-Sasanian deterioration of the written transmission due to incorrect pronunciation

- Errors and corruptions introduced during copying

Many phonetic features cannot be ascribed with certainty to a particular stage since there may be more than one possibility. Every phonetic form that can be ascribed to the Sasanian archetype on the basis of critical assessment of the manuscript evidence must have gone through the stages mentioned above so that "Old Avestan" and "Young Avestan" really mean no more than "Old Avestan and Young Avestan of the Sasanian period".[4]

Alphabet

The script used for writing Avestan developed during the 3rd or 4th century AD. By then the language had been extinct for many centuries, and remained in use only as a liturgical language of the Avesta canon. As is still the case today, the liturgies were memorized by the priesthood and recited by rote.

The script devised to render Avestan was natively known as Din dabireh "religion writing". It has 53 distinct characters and is written right-to-left. Among the 53 characters are about 30 letters that are – through the addition of various loops and flourishes – variations of the 13 graphemes of the cursive Pahlavi script (i.e. "Book" Pahlavi) that is known from the post-Sassanian texts of Zoroastrian tradition. These symbols, like those of all the Pahlavi scripts, are in turn based on Aramaic script symbols. Avestan also incorporates several letters from other writing systems, most notably the vowels, which are mostly derived from Greek minuscules. A few letters were free inventions, as were also the symbols used for punctuation. Also, the Avestan alphabet has one letter that has no corresponding sound in the Avestan language; the character for /l/ (a sound that Avestan does not have) was added to write Pazend texts.

The Avestan script is alphabetic, and the large number of letters suggests that its design was due to the need to render the orally recited texts with high phonetic precision. The correct enunciation of the liturgies was (and still is) considered necessary for the prayers to be effective.

The Zoroastrians of India, who represent one of the largest surviving Zoroastrian communities worldwide, also transcribe Avestan in Brahmi-based scripts. This is a relatively recent development first seen in the ca. 12th century texts of Neryosang Dhaval and other Parsi Sanskritist theologians of that era, which are roughly contemporary with the oldest surviving manuscripts in Avestan script. Today, Avestan is most commonly typeset in the Gujarati script (Gujarati being the traditional language of the Indian Zoroastrians). Some Avestan letters with no corresponding symbol are synthesized with additional diacritical marks, for example, the /z/ in zaraϑuštra is written with j with a dot below.

Phonology

Avestan has retained voiced sibilants, and has fricative rather than aspirate series. There are various conventions for transliteration of Dīn Dabireh, the one adopted for this article being:

Vowels:

- a ā ə ə̄ e ē o ō å ą i ī u ū

Consonants:

- k g γ x xʷ č ǰ t d δ ϑ t̰ p b β f

- ŋ ŋʷ ṇ ń n m y w r s z š ṣ̌ ž h

The glides y and w are often transcribed as ii and uu, imitating Dīn Dabireh orthography. The letter transcribed t̰ indicates an allophone of /t/ with no audible release at the end of a word and before certain obstruents.[9]

Consonants

| Type | Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar or palatal |

Velar | Labiovelar | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | ń /ɲ/ | ŋ /ŋ/ | ŋʷ /ŋʷ/ | ||||||||

| Plosive | p /p/ | b /b/ | t /t/ | d /d/ | č /tʃ/ | ǰ /dʒ/ | k /k/ | g /ɡ/ | |||||

| Fricative | f /ɸ/ | β /β/ | ϑ /θ/ | δ /ð/ | s /s/ | z /z/ | š /ʃ/ | ž /ʒ/ | x /x/ | γ /ɣ/ | xʷ /xʷ/ | h /h/ | |

| Approximant | y /j/ | w /w/ | |||||||||||

| Trill | r /r/ | ||||||||||||

According to Beekes, [ð] and [ɣ] are allophones of /θ/ and /x/ respectively (in Old Avestan).

Grammar

Nouns

| Case | "normal" endings | a-stems: (masc. neut.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| Nominative | -s | -ā | -ō (-as), -ā | -ō (yasn-ō) | -a (vīr-a) | -a (-yasna) |

| Vocative | – | -ā | -ō (-as), -ā | -a (ahur-a) | -a (vīr-a) | -a (yasn-a), -ånghō |

| Accusative | -əm | -ā | -ō (-as, -ns), -ā | -əm (ahur-əm) | -a (vīr-a) | -ą (haom-ą) |

| Instrumental | -ā | -byā | -bīš | -a (ahur-a) | -aēibya (vīr-aēibya) | -āiš (yasn-āiš) |

| Dative | -ē | -byā | -byō (-byas) | -āi (ahur-āi) | -aēibya (vīr-aēibya) | -aēibyō (yasn-aēibyō) |

| Ablative | -at | -byā | -byō | -āt (yasn-āt) | -aēibya (vīr-aēibya) | -aēibyō (yasn-aēibyō) |

| Genitive | -ō (-as) | -å | -ąm | -ahe (ahur-ahe) | -ayå (vīr-ayå) | -anąm (yasn-anąm) |

| Locative | -i | -ō, -yō | -su, -hu, -šva | -e (yesn-e) | -ayō (zast-ayō) | -aēšu (vīr-aēšu), -aēšva |

Verbs

| Person | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | -mi | -vahi | -mahi |

| 2nd | -hi | -tha | -tha |

| 3rd | -ti | -tō, -thō | -ṇti |

Sample text

| Latin alphabet |

Avestan alphabet |

Gujarati script approximation |

English Translation[10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| ahiiā. yāsā. nəmaŋhā. ustānazastō.1 rafəδrahiiā.maniiə̄uš.2 mazdā.3 pouruuīm.4 spəṇtahiiā. aṣ̌ā. vīspə̄ṇg.5 š́iiaoϑanā.6vaŋhə̄uš. xratūm.7 manaŋhō. yā. xṣ̌nəuuīṣ̌ā.8 gə̄ušcā. uruuānəm.9:: (du. bār)::ahiiā. yāsā. nəmaŋhā. ustānazastō. rafəδrahiiā.maniiə̄uš. mazdā. pouruuīm. spəṇtahiiā. aṣ̌ā. vīspə̄ṇg. š́iiaoϑanā.vaŋhə̄uš. xratūm. manaŋhō. yā. xṣ̌nəuuīṣ̌ā. gə̄ušcā. uruuānəm.:: |

|

અહીઆ। યાસા। નામંગહા। ઉસ્તાનજ઼સ્તો।૧ રફ઼ાધરહીઆ।મનીઆઉસ્̌।૨ મજ઼્દા।૩ પોઉરુઉઈમ્।૪ સ્પાણ્તહીઆ। અષ્̌આ। વીસ્પાણ્ગ્।૫ સ્̌́ઇઇઅઓથઅના।૬વંગહાઉસ્̌। ક્સરતૂમ્।૭ મનંગહો। યા। ક્સષ્̌નાઉઉઈષ્̌આ।૮ ગાઉસ્̌ચા। ઉરુઉઆનામ્।૯:: (દુ। બાર્)::અહીઆ। યાસા। નામંગહા। ઉસ્તાનજ઼સ્તો। રફ઼ાધરહીઆ।મનીઆઉસ્̌। મજ઼્દા। પોઉરુઉઈમ્। સ્પાણ્તહીઆ। અષ્̌આ। વીસ્પાણ્ગ્। સ્̌́ઇઇઅઓથઅના।વવંગહાઉસ્̌। ક્સરતૂમ્। મનંગહો। યા। ક્સષ્̌નાઉઉઈષ્̌આ। ગાઉસ્̌ચા। ઉરુઉઆનામ્।:: |

With outspread hands in petition for that help, O Mazda, I will pray for the works of the holy spirit, O thou the Right, whereby I may please the will of Good Thought and the Ox-Soul. |

Example phrases

The following phrases were phonetically transcribed from Avestan:[11]

| Avestan | English | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| tapaiti | It's hot | Can also mean "he is hot" or "she is hot" (in temperature) |

| šiiauuaθa | You move | |

| vō vatāmi | I understand you | |

| mā vātaiiaθa | You teach me | Literally: "You let me understand" |

| dim naiiehi | Thou leadest him/her | |

| dim vō nāiiaiieiti | He/she lets you lead him/her | Present tense |

| mā barahi | Thou carryest me | |

| nō baraiti | He/she carries us | |

| θβā dim bāraiiāmahi | We let him/her carry thee | Present tense |

| drauuāmahi | We run | |

| dīš drāuuaiiāmahi | We let them run | Present tense |

| θβā hacāmi | I follow thee | |

| dīš hācaiieinti | They accompany them | Literally: "They let them follow" |

| ramaiti | He rests | |

| θβā rāmaiiemi | I calm thee | Literally: "I let thee rest" |

See also

Notes

- "It is impossible to attribute a precise geographical location to the language of the Avesta... With the exception of an important study by P. Tedesco (1921 [...]), who advances the theory of an 'Avestan homeland' in northwestern Iran, Iranian scholars of the twentieth century have looked increasingly to eastern Iran for the origins of the Avestan language and today there is general agreement that the area in question was in eastern Iran—a fact that emerges clearly from every passage in the Avesta that sheds any light on its historical and geographical background."[5]

References

- Wells, John C. (1990), Longman pronunciation dictionary, Harlow, England: Longman, p. 53, ISBN 0-582-05383-8 entry "Avestan"

- Witzel, Michael. "THE HOME OF THE ARYANS" (PDF). Harvard University. p. 10. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

Since the evidence of Young Avestan place names so clearly points to a more eastern location, the Avesta is again understood, nowadays, as an East Iranian text, whose area of composition comprised – at least – Sīstån/Arachosia, Herat, Merw and Bactria.

- Mallory, J. P. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture. page 653. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5. entry "Yazd culture".

- Hoffmann, Karl (1989), "Avestan language", Encyclopedia Iranica, 3, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 47–52.

- Gnoli, Gherardo (1989), "Avestan geography", Encyclopedia Iranica, 3, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 44–47.

- Encyclopaedia Iranica: EASTERN IRANIAN LANGUAGES. By Nicholas Sims-Williams

- Hoffmann, K. Encyclopaedia Iranica. AVESTAN LANGUAGE. III. The grammar of Avestan.: "The morphology of Avestan nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and verbs is, like that of the closely related Old Persian, inherited from Proto-Indo-European via Proto-Indo-Iranian (Proto-Aryan), and agrees largely with that of Vedic, the oldest known form of Indo-Aryan. The interpretation of the transmitted Avestan texts presents in many cases considerable difficulty for various reasons, both with respect to their contexts and their grammar. Accordingly, systematic comparison with Vedic is of much assistance in determining and explaining Avestan grammatical forms."

- Morgenstierne, G. Encyclopaedia Iranica: AFGHANISTAN vi. Paṧto "it seems that the Old Iranic ancestor dialect of Paṧtō must have been close to that of the Gathas."

- Hale, Mark (2004). "Avestan". In Roger D. Woodard (ed.). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56256-2.

- "AVESTA: YASNA: Sacred Liturgy and Gathas/Hymns of Zarathushtra". avesta.org.

- Lubotsky, Alexander (2010). Van Sanskriet tot Spijkerschrift: Breinbrekers uit alle talen [From Sanskrit to Cuneiform: Brain teasers from all languages] (in Dutch). Amsterdam University Press. pp. 18, 69–71. ISBN 978-9089641793. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

Sources

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (1988), A Grammar of Gatha-Avestan, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-08332-4.

- Hoffmann, Karl; Forssman, Bernhard (1996), Avestische Laut- und Flexionslehre, Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft 84, Institut fur Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck, ISBN 3-85124-652-7.

- Kellens, Jean (1990), "Avestan syntax", Encyclopedia Iranica, 3/sup, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul

- Skjærvø, Prod Oktor (2006), Old Avestan, fas.harvard.edu.

- Skjærvø, Prod Oktor (2006), Introduction to Young Avestan, fas.harvard.edu.

- Vaan, Michiel (2014), Introduction to Avestan (Brill Introductions to Indo-European Languages, Band 1), Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-25809-9.

External links

- Encyclopedia Avestica, an online etymological glossary covering most of the corpus of the language

- Information on Avestan language at avesta.org

- Old Iranian Online (including Old and Young Avestan) by Scott L. Harvey and Jonathan Slocum, free online lessons at the Linguistics Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Old Avestan and Young Avestan at Harvard University

- Text samples and Avesta Corpus at TITUS.

- Hoffmann, Karl. "Avestan language". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- Boyce, Mary. "Avestan people". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- glottothèque - Ancient Indo-European Grammars online, an online collection of introductory videos to Ancient Indo-European languages produced by the University of Göttingen