Saka language

Saka or Sakan, was a variety of Eastern Iranian languages, attested from the ancient Buddhist kingdoms of Khotan, Kashgar and Tumshuq in the Tarim Basin, in what is now Southern Xinjiang, China. It is a Middle Iranian language.[2] The two kingdoms differed in dialect, their speech known as Khotanese and Tumshuqese.

| Saka | |

|---|---|

| Khotanese, Tumshuqese | |

| Native to | Kingdom of Khotan, Tumshuq, Murtuq and Shule Kingdom[1] |

| Region | Tarim Basin (current China) |

| Ethnicity | Saka |

| Era | 100 BC – 1000 AD |

| Dialects |

|

| Brahmi, Kharosthi | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | kho |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:kho – Khotanesextq – Tumshuqese |

kho (Khotanese) | |

xtq (Tumshuqese) | |

| Glottolog | saka1298 |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Saka rulers of Western India, such as the Indo-Scythians and Western Satraps spoke practically the same language.[3]

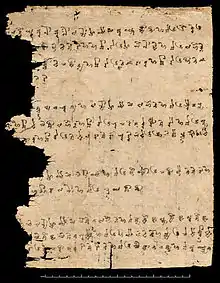

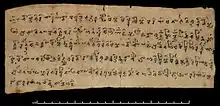

Documents on wood and paper were written in modified Brahmi script with the addition of extra characters over time and unusual conjuncts such as ys for z.[4] The documents date from the fourth to the eleventh century. Tumshuqese was more archaic than Khotanese,[5] but it is much less understood because it appears in fewer manuscripts compared to Khotanese. Both dialects share features with modern Pashto and Wakhi. The language was known as "Hvatanai" in contemporary documents.[6] Many Prakrit terms were borrowed from Khotanese into the Tocharian languages.[7]

History

The two known dialects of Saka are associated with a movement of the Scythians. No invasion of the region is recorded in Chinese records and one theory is that two tribes of the Saka, speaking the two dialects, settled in the region in about 200 BC before the Chinese accounts commence.[8]

The Saka language became extinct after invading Turkic Muslims conquered the Kingdom of Khotan in the Islamicisation and Turkicisation of Xinjiang.

In the 11th century, it was remarked by Mahmud al-Kashgari that the people of Khotan still had their own language and script and did not know Turkic well.[9][10] According to Kashgari some non-Turkic languages like the Kanchaki and Sogdian were still used in some areas.[11] It is believed that the Saka language group was what Kanchaki belonged to.[12] It is believed that the Tarim Basin became linguistically Turkified by the end of the 11th century.[13]

Classification

Khotanese and Tumshuqese are closely related Eastern Iranian languages.[14]

Texts

Other than an inscription from Issyk kurgan that it is tentatively identified as Khotanese (although written in Kharosthi), all of the surviving documents originate from Khotan or Tumshuq. Khotanese is attested from over 2,300 texts[15] preserved among the Dunhuang manuscripts, as opposed to just 15 texts[16] in Tumshuqese. These were deciphered by Harold Walter Bailey.[17] The earliest texts, from the fourth century, are mostly religious documents. There were several viharas in the Kingdom of Khotan and Buddhist translations are common at all periods of the documents. There are many reports to the royal court (called haṣḍa aurāsa) which are of historical importance, as well as private documents. An example of a document is Or.6400/2.3.

Notes

- Mallory, J.P. "Bronze Age languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Expedition. 52 (3): 44–53. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- "Saka language". britannica.com.

- Diringer, David (1948). Alphabet A Key To The History Of Mankind. p. 350.

- Bailey, H W (1970). "The Ancient Kingdom of Khotan". British Institute of Persian Studies. 8: 65–72. doi:10.2307/4299633. JSTOR 4299633.

- Masson], [editors, A.H. Dani, V.M. (1992). History of civilizations of Central Asia. Paris: UNESCO. p. 283. ISBN 92-3-103211-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Bailey, H W (December 1939). "The Rama Story in Khotanese". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 59 (4): 460. doi:10.2307/594480. JSTOR 594480.

- Litvinsky 1999: 432

- Bailey, H W (1970). "The Ancient Kingdom of Khotan". British Institute of Persian Studies. 8: 68.

- http://journals.manas.edu.kg/mjtc/oldarchives/2004/17_781-2049-1-PB.pdf

- Scott Cameron Levi; Ron Sela (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- Scott Cameron Levi; Ron Sela (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- Ahmad Hasan Dani; B. A. Litvinsky; Unesco (1 January 1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. pp. 283–. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- Akiner (28 October 2013). Cultural Change & Continuity In. Routledge. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-136-15034-0.

- Ronald Emmerick, "Khotanese and Tumshuqese", in Gernot Windfuhr, ed., The Iranian Languages, Routledge, 2009

- https://unicode.org/L2/L2015/15022-khotanese.pdf

- "BRĀHMĪ – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- "BAILEY, HAROLD WALTER – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

Sources

International Dunhuang Project

- A Turkish-Khotanese Vocabulary H. W. Bailey Bulletin of the ..

- Bailey, H. W.. 1944. “A Turkish-khotanese Vocabulary”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 11 (2). Cambridge University Press: 290–96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/609315.

Further reading

- ""Prothetic h-" in Khotanese and the reconstruction of Proto-Iranic" (PDF). Martin Kummel. Script and Reconstruction in Linguistic History―Univerzita Karlova v Praze, March 2020.

- Bailey, H W (1979) Dictionary of Khotan Saka, Cambridge University Press

- Encyclopædia Iranica "Iranian Languages" http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/central-asia-xiii

- Emmerick, R. E., & Pulleyblank, E. G. (1993). A Chinese text in Central Asian Brahmi script: new evidence for the pronunciation of Late Middle Chinese and Khotanese. Roma: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. (On connections between Chinese and Khotanese, such as loan words and pronunciations)

- Litvinsky, Boris Abramovich; Vorobyova-Desyatovskaya, M.I (1999). "Religions and religious movements". History of civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 421–448. ISBN 8120815408.

| Look up Khotanese in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |