Parsis

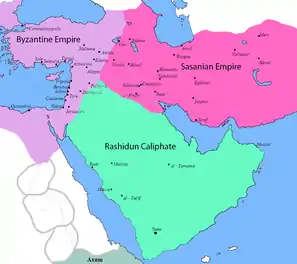

Parsis (/ˈpɑːrsiː/) or Parsees (lit. 'Persian' in the Persian language), are an ethnoreligious group who migrated to the Indian subcontinent from Persia during the Muslim conquest of Persia of 633–654 CE; one of two such groups to have done so, with the other being Iranis. Zoroastrianism is the ethnic religion of the Parsi people. According to the Qissa-i Sanjan, Parsis migrated from the Sasanian Empire to Gujarat, where they were given refuge between the 8th and 10th centuries CE to escape persecution following the Muslim conquests.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

"A Parsi Lady" watercolour painting by M. V. Dhurandhar, c. 1928 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 69,000 (2014)[1][2] | |

| 1,092[3][4] | |

| Languages | |

| English (Indian or Pakistani dialects), Gujarati and Hindi–Urdu | |

| Religion | |

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

|

|

|

At the time of the Muslim conquest of Persia (also known as Iran), the dominant religion of the region (then ruled by the Sasanian Empire) was Zoroastrianism. Many Iranians, such as Babak Khorramdin, rebelled against the Muslim conquerors in Persia for almost 200 years,[12] while other Iranians (who are now called Parsis since their migration to the Indian subcontinent) chose to preserve their religious identities by fleeing from Persia to India during this time.[13]

The word Parsi is derived from the Persian language, and literally translates to Persian (Modern Standard Persian: پارسیان, 'Pārsiān' – i.e. 'Pārsi').[14] Farsi, which is used as the local defining name for the Persian language, is the Arabized form of the word Parsi; the language sees widespread use in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and other regions of the former Persian empires.

The long presence of the Parsis in India distinguishes them from the much more recently-arrived smaller Zoroastrian Indian community of Iranis, who are mostly descendants of the Zoroastrians who fled the repression of the Qajar dynasty and the general socio-political tumult of late 19th- and early 20th-century Iran.[15] D. L. Sheth, the former director of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), lists Indian communities that constituted the middle class and were traditionally "urban and professional" (following professions like doctors, lawyers, teachers, engineers, etc.) immediately after Indian independence in 1947. This list included the Kashmiri Pandits, the Nagar Brahmins from Gujarat, the Brahmins from Southern India, the Punjabi Khatris and Kayasthas from Northern India, the Chitpawans and CKPs from Maharashtra; Bengali Probasis and Bhadraloks, the Parsis, as well as the upper echelons of the Muslim and Christian communities throughout India. According to P. K. Verma, "Education was a common thread that bound together this pan-Indian elite"; almost all of the members of these communities could read and write in English and were educated beyond regular schooling institutions.[16][17][18] As such, Parsis are considered to be a model minority in India.

Definition and identity

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica,

Parsi, also spelled Parsee, member of a group of followers in India of the Persian prophet Zoroaster. The Parsis, whose name means "Persians", are descended from Persian Zoroastrians who emigrated to India to avoid religious persecution by the Muslims. They live chiefly in Mumbai and in a few towns and villages mostly to the south of Mumbai, but also a few minorities nearby in Karachi (Pakistan) and Chennai. There is a sizeable Parsee population in Pune as well in Bangalore. A few Parsee families also reside in Kolkata and Hyderabad. Although they are not, strictly speaking, a caste, since they are not Hindus, they form a well-defined community. The exact date of the Parsi migration is unknown. According to tradition, the Parsis initially settled at Hormuz on the Persian Gulf but finding themselves still persecuted they set sail for India, arriving in the 8th century. The migration may, in fact, have taken place as late as the 10th century, or in both. They settled first at Diu in Kathiawar but soon moved to South Gujarāt, where they remained for about 800 years as a small agricultural community.[19]

The term Pārsi, which in the Persian language is a demonym meaning "inhabitant of Pārs" and hence "ethnic Persian", is not attested in Indian Zoroastrian texts until the 17th century. Until that time, such texts consistently use the Persian-origin terms Zartoshti "Zoroastrian" or Vehdin "[of] the good religion". The 12th-century Sixteen Shlokas, a Sanskrit text in praise of the Parsis,[20] is the earliest attested use of the term as an identifier for Indian Zoroastrians.

The first reference to the Parsis in a European language is from 1322, when a French monk, Jordanus, briefly refers to their presence in Thane and Bharuch. Subsequently, the term appears in the journals of many European travelers, first French and Portuguese, later English, all of whom used a Europeanized version of an apparently local language term. For example, Portuguese physician Garcia de Orta observed in 1563 that "there are merchants ... in the kingdom of Cambaia ... known as Esparcis. We Portuguese call them Jews, but they are not so. They are Gentios." In an early 20th-century legal ruling (see self-perceptions, below), Justices Davar and Beaman asserted (1909:540) that "Parsi" was also a term used in Iran to refer to Zoroastrians.[21][22] notes that in much the same way as the word "Hindu" was used by Iranians to refer to anyone from the Indian subcontinent, "Parsi" was used by the Indians to refer to anyone from Greater Iran, irrespective of whether they were actually ethnic Persian people. In any case, the term "Parsi" itself is "not necessarily an indication of their Iranian or 'Persian' origin, but rather as indicator – manifest as several properties – of ethnic identity".[23] Moreover, if heredity were the only factor in a determination of ethnicity, the Parsis would count as Parthians according to the Qissa-i Sanjan.[22]

The term "Parseeism" or "Parsiism", is attributed to Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron, who in the 1750s, when the word "Zoroastrianism" had yet to be coined, made the first detailed report of the Parsis and of Zoroastrianism, therein mistakenly assuming that the Parsis were the only remaining followers of the religion.

In addition to above, the term "Parsi" existed even before they moved to India:

- The earliest reference to the Parsis is found in the Assyrian inscription of Shalmaneser III (circa 854-824 BC).

- Darius the Great (521-486 BC) establishes this fact when he records his Parsi ancestry for posterity, “parsa parsahya puthra ariya ariyachitra”, meaning, “a Parsi, the son of a Parsi, an Aryan, of Aryan family (Inscription at Naqsh-i-Rustam, near Persepolis, Iran).

- In Outlines of Parsi History, Dasturji Hormazdyar Dastur Kayoji Mirza, Bombay 1987, pp. 3-4 writes, “According to the Pahlavi text of Karnamak i Artakhshir i Papakan, the Indian astrologer refers to Artakhshir (Sasanian king, and the founder of the Empire) as khvatay parsikan ‘the king of the Parsis’.

- Herodotus and Xenophon, the two great historians who lived in the third and fourth centuries BC referred to Iranians as Parsis.[24]

Origins

In ancient Persia, Zoroaster taught that good (Ohrmazd) and evil (Angra Mainyu) were opposite forces and the battle between them is more or less evenly matched. A person should always be vigilant to align with forces of light. According to the asha or the righteousness and druj or the wickedness, the person has chosen in his life they will be judged at the Chinvat bridge to grant passage to Paradise, Hammistagan (A limbo area) or Hell by a sword. A personified form of the soul that represents the person’s deeds takes the adjudged to their destination and they will abide there until the final apocalypse. After the final battle between good and evil, every soul’s walk through a river of fire ordeal for burning of their dross and together they receive a post resurrection paradise. The Zoroastrian holy book, called the Avesta, was written in the Avestan language, which is closely related to Vedic Sanskrit.

The Qissa-i Sanjan is a tale of the journey of the Parsis to India from Iran. It says they fled for reasons of religious freedom and they were allowed to settle in India thanks to the goodwill of a local prince. However, the Parsi community had to abide by three rules: they had to speak the local language, follow local marriage customs, and not carry any weapons. After showing the many similarities between their faith and local beliefs, the early community was granted a plot of land on which to build a fire temple.

As an ethnic community

Over the centuries since the first Zoroastrians arrived in India, the Parsis have integrated themselves into Indian society while simultaneously maintaining or developing their own distinct customs and traditions (and thus ethnic identity). This in turn has given the Parsi community a rather peculiar standing: they are Indians in terms of national affiliation, language and history, but not typically Indian in terms of consanguinity or ethnicity, cultural, behavioural and religious practices. Genealogical DNA tests to determine purity of lineage have brought mixed results. One study supports the Parsi contention that they have maintained their Persian roots by avoiding intermarriage with local populations. In that 2002 study of the Y-chromosome (patrilineal) DNA of the Parsis of Pakistan, it was determined that Parsis are genetically closer to Iranians than to their neighbours.[26]

A 2004 study in which Parsi mitochondrial DNA (matrilineal) was compared with that of the Iranians and Gujaratis determined that Parsis are genetically closer to Gujaratis than to Iranians. Taking the 2002 study into account, the authors of the 2004 study suggested "a male-mediated migration of the ancestors of the present-day Parsi population, where they admixed with local females [...] leading ultimately to the loss of mtDNA of Iranian origin".[27] A study was conducted in 2017 which found that Parsis are genetically closer to Neolithic Iranians than to modern Iranians, who have witnessed a more recent wave of admixture from the Near East and that there were “48% South-Asian-specific mitochondrial lineages among the ancient samples, which might have resulted from the assimilation of local females during the initial settlement.”[28]

Self-perceptions

The definition of who is, and is not, a Parsi is a matter of great contention within the Zoroastrian community in India. It is generally accepted that a Parsi is a person who:

- (a) is directly descended from the original Persian refugees, and

- (b) has been formally admitted into the Zoroastrian religion, through the navjote ceremony.

In this sense, Parsi is an ethno-religious designator, whose definition is of contention among its members, similar to the contention over who is a Jew in the West.

Some members of the community additionally contend that a child must have a Parsi father to be eligible for introduction into the faith, but this assertion is considered by most to be a violation of the Zoroastrian tenets of gender equality and may be a remnant of an old legal definition of the term Parsi.

An oft-quoted legal definition of Parsi is based on a 1909 ruling (since nullified) that not only stipulated that a person could not become a Parsi by converting to the Zoroastrian faith but also noted:

the Parsi community consists of: a) Parsis who are descended from the original Persian emigrants and who are born of both Zoroastrian parents and who profess the Zoroastrian religion; b) Iranis [here meaning Iranians, not the other group of Indian Zoroastrians] professing the Zoroastrian religion; c) the children of Parsi fathers by alien mothers who have been duly and properly admitted into the religion.[29]

This definition was overturned several times. The equality principles of the Indian Constitution void the patrilineal restrictions expressed in the third clause. The second clause was contested and overturned in 1948.[30] On appeal in 1950, the 1948 ruling was upheld and the entire 1909 definition was deemed an obiter dictum – a collateral opinion and not legally binding (re-affirmed in 1966).[31][32])

There is a growing voice within the community that if indeed equality must be re-established then the only acceptable solution is to allow a child to be initiated into the faith only if both parents are Parsi.

Nonetheless, the opinion that the 1909 ruling is legally binding continues to persist, even among the better-read and moderate Parsis.

Population

According to the 2011 Census of India, there are 57,264 Parsis in India.[34][35] According to the National Commission for Minorities, there are a "variety of causes that are responsible for this steady decline in the population of the community", the most significant of which were childlessness and migration-[36] Demographic trends project that by the year 2020 the Parsis will number only 23,000. The Parsis will then cease to be called a community and will be labeled a 'tribe'.[37]

One-fifth of the decrease in population is attributed to migration.[38] A slower birthrate than deathrate accounts for the rest: as of 2001, Parsis over the age of 60 make up for 31% of the community. Only 4.7% of the Parsi community are under 6 years of age, which translates to 7 births per year per 1000 individuals.[39] Concerns have been raised in recent years over the rapidly declining population of the Parsi community in India.[40]

Other demographic statistics

The gender ratio among Parsis is unusual: as of 2001, the ratio of males to females was 1000 males to 1050 females (up from 1024 in 1991), due primarily to the high median age of the population (elderly women are more common than elderly men). As of 2001 the national average in India was 1000 males to 933 females.

Parsis have a high literacy rate; as of 2001, the literacy rate is 97.9%, the highest of any Indian community (the national average was 64.8%). 96.1% of Parsis reside in urban areas (the national average is 27.8%). Parsis mother tongue is Gujarati.

In the Greater Mumbai area, where the density of Parsis is highest, about 10% of Parsi females and about 20% of Parsi males do not marry.[41]

History

Arrival in the Indian sub-continent

According to the Qissa-i Sanjan, the only existing account of the early years of Zoroastrian refugees in India composed at least six centuries after their tentative date of arrival, the first group of immigrants originated from Greater Khorasan.[5] This historical region of Central Asia is in part in northeastern Iran, where it constitutes modern Khorasan Province, part of western/northern Afghanistan, and in part in three Central-Asian republics namely Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

According to the Qissa, the immigrants were granted permission to stay by the local ruler, Jadi Rana, on the condition that they adopt the local language (Gujarati) and that their women adopt local dress (the sari).[42] The refugees accepted the conditions and founded the settlement of Sanjan, which is said to have been named after the city of their origin (Sanjan, near Merv, modern Turkmenistan).[5] This first group was followed by a second group from Greater Khorasan within five years of the first, and this time having religious implements with them (the alat). In addition to these Khorasanis or Kohistanis "mountain folk", as the two initial groups are said to have been initially called,[43] at least one other group is said to have come overland from Sari, Iran.[44]

Although the Sanjan group are believed to have been the first permanent settlers, the precise date of their arrival is a matter of conjecture. All estimates are based on the Qissa, which is vague or contradictory with respect to some elapsed periods. Consequently, three possible dates – 716, 765, and 936 – have been proposed as the year of landing, and the disagreement has been the cause of "many an intense battle ... amongst Parsis".[45] Since dates are not specifically mentioned in Parsi texts prior to the 18th century, any date of arrival is perforce a matter of speculation. The importance of the Qissa lies in any case not so much in its reconstruction of events than in its depiction of the Parsis – in the way they have come to view themselves – and in their relationship to the dominant culture. As such, the text plays a crucial role in shaping Parsi identity. But, "even if one comes to the conclusion that the chronicle based on verbal transmission is not more than a legend, it still remains without doubt an extremely informative document for Parsee historiography."[46]

The Sanjan Zoroastrians were certainly not the first Zoroastrians on the subcontinent. Sindh touching Balochistan, the easternmost periphery of the Iranian world, too had once been under coastal administration of the Sasanian Empire (226-651), which consequently maintained outposts there. Even following the loss of Sindh, the Iranians continued to play a major role in the trade links between the east and west. The 9th-century Arab historiographer Al-Masudi briefly notes Zoroastrians with fire temples in al-Hind and in al-Sindh.[47] There is evidence of individual Parsis residing in Sindh in the tenth and twelfth centuries, but the current modern community is thought to date from British arrival in Sindh.[48] Moreover, for the Iranians, the harbours of Gujarat lay on the maritime routes that complemented the overland Silk Road and there were extensive trade relations between the two regions. The contact between Iranians and Indians was already well established even prior to the Common Era, and both the Puranas and the Mahabharata use the term Parasikas to refer to the peoples west of the Indus River.[49]

"Parsi legends regarding their ancestors' migration to India depict a beleaguered band of religious refugees escaping the new rule post the Muslim conquests in order to preserve their ancient faith."[49][50][6][7][8] However, while Parsi settlements definitely arose along the western coast of the Indian subcontinent following the Arab conquest of Iran, it is not possible to state with certainty that these migrations occurred as a result of religious persecution against Zoroastrians. If the "traditional" 8th century date (as deduced from the Qissa) is considered valid, it must be assumed "that the migration began while Zoroastrianism was still the predominant religion in Iran [and] economic factors predominated the initial decision to migrate."[49] This would have been particularly the case if – as the Qissa suggests – the first Parsis originally came from the north-east (i.e. Central Asia) and had previously been dependent on Silk Road trade.[21] Even so, in the 17th century, Henry Lord, a chaplain with the English East India Company, noted that the Parsis came to India seeking "liberty of conscience" but simultaneously arrived as "merchantmen bound for the shores of India, in course of trade and merchandise." The fact that Muslims charged non-Muslims higher duties when trading from Muslim-held ports may be interpreted to be a form of religious persecution, but this being the only reason to migrate appears unlikely.

Early years

The Qissa has little to say about the events that followed the establishment of Sanjan, and restricts itself to a brief note on the establishment of the "Fire of Victory" (Middle Persian: Atash Bahram) at Sanjan and its subsequent move to Navsari. According to Dhalla, the next several centuries were "full of hardships" (sic) before Zoroastrianism "gained a real foothold in India and secured for its adherents some means of livelihood in this new country of their adoption".[51]

Two centuries after their landing, the Parsis began to settle in other parts of Gujarat, which led to "difficulties in defining the limits of priestly jurisdiction."[52] These problems were resolved by 1290 through the division of Gujarat into five panthaks (districts), each under the jurisdiction of one priestly family and their descendants. (Continuing disputes regarding jurisdiction over the Atash Bahram led to the fire being moved to Udvada in 1742, where today jurisdiction is shared in rotation among the five panthak families.)

Inscriptions at the Kanheri Caves near Mumbai suggest that at least until the early 11th century, Middle Persian was still the literary language of the hereditary Zoroastrian priesthood. Nonetheless, aside from the Qissa and the Kanheri inscriptions, there is little evidence of the Parsis until the 12th and 13th century, when "masterly"[53] Sanskrit translations and transcriptions of the Avesta and its commentaries began to be prepared. From these translations Dhalla infers that "religious studies were prosecuted with great zeal at this period" and that the command of Middle Persian and Sanskrit among the clerics "was of a superior order".[53]

From the 13th century to the late 16th century, the Zoroastrian priests of Gujarat sent (in all) twenty-two requests for religious guidance to their co-religionists in Iran, presumably because they considered the Iranian Zoroastrians "better informed on religious matters than themselves, and must have preserved the old-time tradition more faithfully than they themselves did".[54] These transmissions and their replies – assiduously preserved by the community as the rivayats (epistles) – span the years 1478–1766 and deal with both religious and social subjects. From a superficial 21st century point of view, some of these ithoter ("questions") are remarkably trivial – for instance, Rivayat 376: whether ink prepared by a non-Zoroastrian is suitable for copying Avestan language texts – but they provide a discerning insight into the fears and anxieties of the early modern Zoroastrians. Thus, the question of the ink is symptomatic of the fear of assimilation and the loss of identity, a theme that dominates the questions posed and continues to be an issue into the 21st century. So also the question of conversion of Juddins (non-Zoroastrians) to Zoroastrianism, to which the reply (R237, R238) was: acceptable, even meritorious.[55]

Nonetheless, "the precarious condition in which they lived for a considerable period made it impracticable for them to keep up their former proselytizing zeal. The instinctive fear of disintegration and absorption in the vast multitudes among whom they lived created in them a spirit of exclusiveness and a strong desire to preserve the racial characteristics and distinctive features of their community. Living in an atmosphere surcharged with the Hindu caste system, they felt that their own safety lay in encircling their fold by rigid caste barriers".[56] Even so, at some point (possibly shortly after their arrival in India), the Zoroastrians – perhaps determining that the social stratification that they had brought with them was unsustainable in the small community – did away with all but the hereditary priesthood (called the asronih in Sassanid Iran). The remaining estates – the (r)atheshtarih (nobility, soldiers, and civil servants), vastaryoshih (farmers and herdsmen), hutokshih (artisans and labourers) – were folded into an all-comprehensive class today known as the behdini ("followers of daena", for which "good religion" is one translation). This change would have far reaching consequences. For one, it opened the gene pool to some extent since until that time inter-class marriages were exceedingly rare (this would continue to be a problem for the priesthood until the 20th century). For another, it did away with the boundaries along occupational lines, a factor that would endear the Parsis to the 18th- and 19th-century colonial authorities who had little patience for the unpredictable complications of the Hindu caste system (such as when a clerk from one caste would not deal with a clerk from another).

Age of opportunity

Following the commercial treaty in the early 17th century between Mughal emperor Jahangir and James I of England, the East India Company obtained the exclusive rights to reside and build factories in Surat and other areas. Many Parsis, who until then had been living in farming communities throughout Gujarat, moved to the English-run settlements to take the new jobs offered. In 1668 the English East India Company leased the Seven Islands of Bombay from Charles II of England. The company found the deep harbour on the east coast of the islands to be ideal for setting up their first port in the sub-continent, and in 1687 they transferred their headquarters from Surat to the fledgling settlement. The Parsis followed and soon began to occupy posts of trust in connection with government and public works.[57]

Where literacy had previously been the exclusive domain of the priesthood, in the era of the British Raj, the British schools in India provided the new Parsi youth with the means not only to learn to read and write but also to be educated in the greater sense of the term and become familiar with the quirks of the British establishment. These capabilities were enormously useful to Parsis since they allowed them to "represent themselves as being like the British," which they did "more diligently and effectively than perhaps any other South Asian community".[58] While the colonial authorities often saw the other Indians "as passive, ignorant, irrational, outwardly submissive but inwardly guileful",[59] the Parsis were seen to have the traits that the authorities tended to ascribe to themselves. Johan Albrecht de Mandelslo (1638) saw them as "diligent", "conscientious", and "skillful" in their mercantile pursuits. Similar observations would be made by James Mackintosh, Recorder of Bombay from 1804 to 1811, who noted that "the Parsees are a small remnant of one of the mightiest nations of the ancient world, who, flying from persecution into India, were for many ages lost in obscurity and poverty, till at length they met a just government under which they speedily rose to be one of the most popular mercantile bodies in Asia".[60]

One of these was an enterprising agent named Rustom Maneck. In 1702, Maneck, who had probably already amassed a fortune under the Dutch and Portuguese, was appointed the first broker to the East India Company (acquiring the name "Seth" in the process), and in the following years "he and his Parsi associates widened the occupational and financial horizons of the larger Parsi community".[61] Thus, by the mid-18th century, the brokerage houses of the Bombay Presidency were almost all in Parsi hands. As James Forbes, the Collector of Broach (now Bharuch), would note in his Oriental Memoirs (1770): "many of the principal merchants and owners of ships at Bombay and Surat are Parsees." "Active, robust, prudent and persevering, they now form a very valuable part of the Company's subjects on the western shores of Hindustan where they are highly esteemed".[60]In the 18th century, Parsis with their skills in ship building and trade greatly benefited with trade between India and China.The trade was mainly in timber, silk, cotton and opium. For example Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy acquired most of his wealth through trade in cotton and opium[62] Gradually certain families "acquired wealth and prominence (Sorabji, Modi, Cama, Wadia, Jeejeebhoy, Readymoney, Dadyseth, Petit, Patel, Mehta, Allbless, Tata, etc.), many of which would be noted for their participation in the public life of the city, and for their various educational, industrial, and charitable enterprises."[63][64]).

Through his largesse, Maneck helped establish the infrastructure that was necessary for the Parsis to set themselves up in Bombay and in doing so "established Bombay as the primary centre of Parsi habitation and work in the 1720s".[61] Following the political and economic isolation of Surat in the 1720s and 1730s that resulted from troubles between the (remnant) Mughal authorities and the increasingly dominant Marathas, a number of Parsi families from Surat migrated to the new city. While in 1700 "fewer than a handful of individuals appear as merchants in any records; by mid-century, Parsis engaged in commerce constituted one of important commercial groups in Bombay".[65] Maneck's generosity is incidentally also the first documented instance of Parsi philanthropy. In 1689, Anglican chaplain John Ovington reported that in Surat the family "assist the poor and are ready to provide for the sustenance and comfort of such as want it. Their universal kindness, either employing such as are ready and able to work, or bestowing a seasonable bounteous charity to such as are infirm and miserable, leave no man destitute of relief, nor suffer a beggar in all their tribe".[66]

_in_Bombay_1873.jpg.webp)

In 1728 Rustom's eldest son Naoroz (later Naorojee) founded the Bombay Parsi Panchayet (in the sense of an instrument for self-governance and not in the sense of the trust it is today) to assist newly arriving Parsis in religious, social, legal and financial matters. Using their vast resources, the Maneck Seth family gave their time, energy and not inconsiderable financial resources to the Parsi community, with the result that by the mid-18th century, the Panchayat was the accepted means for Parsis to cope with the exigencies of urban life and the recognized instrument for regulating the affairs of the community.[67] Nonetheless, by 1838 the Panchayat was under attack for impropriety and nepotism. In 1855 the Bombay Times noted that the Panchayat was utterly without the moral or legal authority to enforce its statutes (the Bundobusts or codes of conduct) and the council soon ceased to be considered representative of the community.[68] In the wake of a July 1856 ruling by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council that it had no jurisdiction over the Parsis in matters of marriage and divorce, the Panchayat was reduced to little more than a Government-recognized "Parsi Matrimonial Court". Although the Panchayat would eventually be reestablished as the administrator of community property, it ultimately ceased to be an instrument for self-governance.[69]

At about the same time as the role of the Panchayat was declining, a number of other institutions arose that would replace the Panchayat's role in contributing to the sense of social cohesiveness that the community desperately sought. By the mid-19th century, the Parsis were keenly aware that their numbers were declining and saw education as a possible solution to the problem. In 1842 Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy established the Parsi Benevolent Fund with the aim of improving, through education, the condition of the impoverished Parsis still living in Surat and its environs. In 1849 the Parsis established their first school (co-educational, which was a novelty at the time, but would soon be split into separate schools for boys and girls) and the education movement quickened. The number of Parsi schools multiplied, but other schools and colleges were also freely attended.[70] Accompanied by better education and social cohesiveness, the community's sense of distinctiveness grew, and in 1854 Dinshaw Maneckji Petit founded the Persian Zoroastrian Amelioration Fund with the aim of improving conditions for his less fortunate co-religionists in Iran. The fund succeeded in convincing a number of Iranian Zoroastrians to emigrate to India (where they are known today as Iranis) and the efforts of its emissary Maneckji Limji Hataria may have been instrumental in obtaining a remission of the jizya for their co-religionists in 1882.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Parsis had emerged as "the foremost people in India in matters educational, industrial, and social. They came in the vanguard of progress, amassed vast fortunes, and munificently gave away large sums in charity".[71] Near the end of the 19th century, the total number of Parsis in colonial India was 85,397, of which 48,507 lived in Bombay, constituting around 6.7% of the total population of the city, according to the 1881 census.[72] This would be the last time that the Parsis would be considered a numerically significant minority in the city.

Nonetheless, the legacy of the 19th century was a sense of self-awareness as a community. The typically Parsi cultural symbols of the 17th and 18th centuries such as language (a Parsi variant of Gujarati), arts, crafts, and sartorial habits developed into Parsi theatre, literature, newspapers, magazines, and schools. The Parsis now ran community medical centres, ambulance corps, Scouting troops, clubs, and Masonic Lodges. They had their own charitable foundations, housing estates, legal institutions, courts, and governance. They were no longer weavers and petty merchants, but now were established and ran banks, mills, heavy industry, shipyards, and shipping companies. Moreover, even while maintaining their own cultural identity they did not fail to recognize themselves as nationally Indian, as Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Asian to occupy a seat in the British Parliament would note: "Whether I am a Hindu, a Mohammedan, a Parsi, a Christian, or of any other creed, I am above all an Indian. Our country is India; our nationality is Indian".[73] At the time of Indian independence movement, the Parsis opposed the partition of India.[74]

Religious practices

The main components of Zoroastrianism as practiced by the Parsi community are the concepts of purity and pollution (nasu), initiation (navjot), daily prayers, worship at Fire Temples, marriage, funerals, and general worship.

Purity and pollution

The balance between good and evil is correlated to the idea of purity and pollution. Purity is held to be of the very essence of godliness. Pollution's very point is to destroy purity through the death of a human. In order to adhere to purity it is the duty of Parsis to continue to preserve purity within their body as God created them. A Zoroastrian priest spends his entire life dedicated to following a holy life.

Navjote

Zoroastrians are not initiated by infant baptism. A child is initiated into the faith when he or she is old enough to enter into the faith as the child requires to recite some prayers along with the priest at the time of Navjote ceremony ideally before they hit puberty. Though there is no actual age before which a child must be initiated into the faith (preferably after 7 years), Navjote cannot be performed on an adult.

The initiation begins with a ritual bath, then a spiritual cleansing prayer; the child changes into white pajama pants, a shawl, and a small cap. Following introductory prayers, the child is given the sacred items that are associated with Zoroastrianism: a sacred shirt and cord, sudre, and kusti. The child then faces the main priest and fire is brought in to represent God. Once the priest finishes with the prayers, the child’s initiation is complete and he or she is now a part of the community and religion.

Marriage

Marriage is very important to the members of the Parsi community, believing that in order to continue the expansion of God’s kingdom they must procreate. Up until the mid-19th century child marriages were common even though the idea of child marriage was not part of the religious doctrine. Consequently, when social reform started happening in India, the Parsi community discontinued the practice. There are, however, rising problems over the availability of brides. More and more women in the Parsi community are becoming well educated and are therefore either delaying marriage or not partaking at all. Women within the Parsi community in India are ninety-seven percent literate; forty-two percent have completed high school or college and twenty-nine percent have an occupation in which they earn a substantial amount of money. The wedding ceremony begins much like the initiation with a cleansing bath. The bride and groom then travel to the wedding in florally decorated cars. The priests from both families facilitate the wedding. The couple begins by facing one another with a sheet to block their view of one another. Wool is passed over the two seven times to bind them together. The two are then supposed to throw rice to their partner symbolizing dominance. The religious element comes in next when the two sit side by side to face the priest.

Funerals

The pollution that is associated with death has to be handled carefully. A separate part of the home is designated to house the corpse for funeral proceedings before being taken away. The priest comes to say prayers that are for the cleansing of sins and to affirm the faith of the deceased. Fire is brought to the room and prayers are begun. The body is washed and inserted clean within a sudre and kusti. The ceremony then begins, and a circle is drawn around the body into which only the bearers may enter. As they proceed to the cemetery they walk in pairs and are connected by white fabric. A dog is essential in the funeral process because it is able to see death. The body is taken to the tower of death where the vultures feed on it. Once the bones are bleached by the sun they are pushed into the circular opening in the center. The mourning process is four days long, and rather than creating graves for the dead, charities are established in honor of the person.

Temples

.jpg.webp)

Zoroastrian festivals were originally held outside in the open air; temples were not common until later. Most of the temples were built by wealthy Parsis who needed centers that housed purity. As stated before, fire is considered to represent the presence of Ahura Mazda, and there are two distinct differences for the types of fire for the different temples. The first type of temple is the Atash Behram, which is the highest level of fire. The fire is prepared for an entire year before it can be installed, and once it is, it is cared for to the highest possible degree. There are only eight such temples located within India. The second type of fire temple is called a Dar-i Mihr, and the preparation process is not as intense. There are about 160 of these located throughout India.

Factions within the community

Calendrical differences

This section contains information specific to the Parsi calendar. For information on the calendar used by the Zoroastrians for religious purposes, including details on its history and its variations, see Zoroastrian calendar.

Until about the 12th century, all Zoroastrians followed the same 365-day religious calendar, which had remained largely unmodified since the calendar reforms of Ardashir I (r. 226-241 AD). Since that calendar did not compensate for the fractional days that go to make up a full solar year, with time it was no longer accordant with the seasons.

Sometime between 1125 and 1250 (cf. Boyce 1970, p. 537), the Parsis inserted an embolismic month to level out the accumulating fractional days. However, the Parsis were the only Zoroastrians to do so (and did it only once), with the result that, from then on, the calendar in use by the Parsis and the calendar in use by Zoroastrians elsewhere diverged by a matter of thirty days. The calendars still had the same name, Shahenshahi (imperial), presumably because none were aware that the calendars were no longer the same.

In 1745 the Parsis in and around Surat switched to the Kadmi or Kadimi calendar on the recommendation of their priests who were convinced that the calendar in use in the ancient homeland must be correct. Moreover, they denigrated the Shahenshahi calendar as being "royalist".

In 1906 attempts to bring the two factions together resulted in the introduction of a third calendar based on an 11th-century Seljuk model: the Fasili, or Fasli, calendar had leap days intercalated every four years and it had a New Year's day that fell on the day of the vernal equinox. Although it was the only calendar always in harmony with the seasons, most members of the Parsi community rejected it on the grounds that it was not in accord with the injunctions expressed in Zoroastrian tradition (Dēnkard 3.419).

Today the majority of Parsis are adherents of the Parsi version of the Shahenshahi calendar although the Kadmi calendar does have its adherents among the Parsi communities of Surat and Bharuch. The Fasli calendar does not have a significant following among Parsis, but, by virtue of being compatible with the Bastani calendar (an Iranian development with the same salient features as the Fasli calendar), it is predominant among the Zoroastrians of Iran.

Effect of the calendar disputes

Since some of the Avesta prayers contain references to the names of the months, and some other prayers are used only at specific times of the year, the issue of which calendar is "correct" also has theological ramifications.

To further complicate matters, in the late 18th century (or early 19th century) a highly influential head-priest and staunch proponent of the Kadmi calendar, Phiroze Kaus Dastur of the Dadyseth Atash-Behram in Bombay, became convinced that the pronunciation of prayers as recited by visitors from Iran was correct, while the pronunciation as used by the Parsis was not. He accordingly went on to alter some (but not all) of the prayers, which in due course came to be accepted by all adherents of the Kadmi calendar as the more ancient (and thus presumably correct). However, scholars of Avestan language and linguistics attribute the difference in pronunciation to a vowel-shift that occurred only in Iran and that the Iranian pronunciation as adopted by the Kadmis is actually more recent than the pronunciation used by the non-Kadmi Parsis.

The calendar disputes were not always purely academic, either. In the 1780s, emotions over the controversy ran so high that violence occasionally erupted. In 1783 a Shahenshahi resident of Bharuch named Homaji Jamshedji was sentenced to death for kicking a young Kadmi woman and so causing her to miscarry.

Of the eight Atash-Behrams (the highest grade of fire temple) in India, three follow the Kadmi pronunciation and calendar, the other five are Shahenshahi. The Fassalis do not have their own Atash-Behram.

Ilm-e-Kshnoom

The Ilm-e-Kshnoom ('science of ecstasy', or 'science of bliss') is a school of Parsi-Zoroastrian philosophy based on a mystic and esoteric, rather than literal, interpretation of religious texts. According to adherents of the sect, they are followers of the Zoroastrian faith as preserved by a clan of 2000 individuals called the Saheb-e-Dilan ('Masters of the Heart') who are said to live in complete isolation in the mountainous recesses of the Caucasus (alternatively, in the Alborz range, around Mount Damavand).

There are few obvious indications that a Parsi might be a follower of the Kshnoom. Although their Kusti prayers are very similar to those used by the Fassalis, like the rest of the Parsi community the followers of Kshnoom are divided with respect to which calendar they observe. There are also other minor differences in their recitation of the liturgy, such as repetition of some sections of the longer prayers. Nonetheless, the Kshnoom are extremely conservative in their ideology and prefer isolation even with respect to other Parsis.

The largest community of followers of the Kshnoom lives in Jogeshwari, a suburb of Bombay, where they have their own fire temple (Behramshah Nowroji Shroff Daremeher), their own housing colony (Behram Baug) and their own newspaper (Parsi Pukar). There is a smaller concentration of adherents in Surat, where the sect was founded in the last decades of the 19th century.

Issues relating to the deceased

It has been traditional, in Mumbai and Karachi at least, for dead Parsis to be taken to the Towers of Silence where the corpses are quickly eaten by the city's vultures. The reason given for this practice is that earth, fire, and water are considered sacred elements which should not be defiled by the dead. Therefore, burial and cremation have always been prohibited in Parsi culture. However, in modern day Mumbai and Karachi the population of vultures has drastically reduced due to extensive urbanization and the unintended consequence of treating humans and livestock with antibiotics,[75] and the anti-inflammatory diclofenac, which harm vultures and have led to the Indian vulture crisis.[76] As a result, the bodies of the deceased are taking much longer to decompose. Solar panels have been installed in the Towers of Silence to speed up the decomposition process, but this has been only partially successful especially during monsoons. In Peshawar a Parsi graveyard was established in the late 19th century, which still exists; this cemetery is unique as there is no Tower of Silence. Nevertheless, the majority of Parsis still use the traditional method of disposing of their loved ones and consider this as the last act of charity by the deceased on earth.

The Tower of Silence in Mumbai is located at Malabar Hill. In Karachi, the Tower of Silence is located in Parsi Colony, near the Chanesar Goth and Mehmoodabad localities.[77]

Archaeogenetics

The genetic studies of Parsis of Pakistan show sharp contrast between genetic data obtained from mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and Y-chromosome DNA (Y-DNA), different from most populations. Historical records suggests that they had moved from Iran to Gujarat, India and then to Mumbai and Karachi, Pakistan. According to Y-DNA, they resemble the Iranian population, which supports historical records. When the mtDNA pool is compared to Iranians and Gujaratis (their putative parental populations), it contrasted Y-DNA data. About 60% of their maternal gene pool originates from South Asian haplogroups, which is just 7% in Iranians. Parsis have a high frequency of haplogroup M (55%), similar to Indians, which is just 1.7% in combined Iranian sample. The studies suggest sharp contrast between the maternal and paternal component of Parsis. Due to high diversity in Y-DNA and mtDNA lineages, the strong drift effect is unlikely even though they had a small population. The studies suggest a male-mediated migration of Parsi ancestors from Iran to Gujarat where they admixed with the local female population during initial settlements, which ultimately resulted in loss of Iranian mtDNA.[78][79]

A study published in Genome Biology based on high density SNP data has shown that the Parsis are genetically closer to Iranian populations than to their South Asian neighbours. They also share the highest number of haplotypes with present-day Iranians; the admixture of the Parsis with Indian populations was estimated have occurred approximately 1,200 years ago. It is also found that Parsis are genetically closer to Neolithic Iranians than to modern Iranians who had recently received some genes from the Near East.[79]

Parsis have been shown to have high rates of breast cancer[80] bladder cancer, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and Parkinson's disease.[81]

Prominent Parsis

The Parsis have made considerable contributions to the history and development of India, all the more remarkable considering their small numbers. As the maxim "Parsi, thy name is charity" alludes to, their most prominent contribution is their philanthropy.

Although their people's name Parsi comes from the Persian-language word for a Persian person, in Sanskrit the term means "one who gives alms".[10][11] Mahatma Gandhi would note in a much misquoted statement,[82] "I am proud of my country, India, for having produced the splendid Zoroastrian stock, in numbers beneath contempt, but in charity and philanthropy perhaps unequaled and certainly unsurpassed."[83] Several landmarks in Mumbai are named after Parsis, including Nariman Point. The Malabar Hill in Mumbai, is a home to several prominent Parsis. Parsis prominent in the Indian independence movement include Pherozeshah Mehta, Dadabhai Naoroji, and Bhikaiji Cama.

Particularly notable Parsis in the fields of science and industry include physicist Homi J. Bhabha, Homi N. Sethna, J. R. D. Tata and Jamsetji Tata, regarded as the "Father of Indian Industry". Karachi-based businessman Byram Dinshawji Avari is the founder of Avari Group of companies, and is a twice Asian Games gold medalist.[84] The families Godrej, Tata, Petit, Cowasjee and Wadia are important industrial Parsi families.

Other Parsi businessmen are Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata, J. R. D. Tata, Dinshaw Maneckji Petit, Ness Wadia, Neville Wadia, Jehangir Wadia and Nusli Wadia—all of them related through marriage to Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. Mohammad Ali Jinnah's wife Rattanbai Petit, was born into two of the Parsi Petit–Tata families, and their daughter Dina Jinnah was married to Parsi industrialist Neville Wadia, the scion of the Wadia family. The husband of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and son-in-law of Jawaharlal Nehru, Feroze Gandhi, was a Parsi with ancestral roots in Bharuch.

The Parsi community has given India several distinguished military officers. Field Marshal Sam Hormusji Framji Jamshedji Manekshaw, Military Cross, the architect of India's victory in the 1971 war, was the first officer of the Indian Army to be appointed a Field Marshal. Admiral Jal Cursetji was the first Parsi to be appointed Chief of the Naval Staff of the Indian Navy. Air Marshal Aspy Engineer served as India's second Chief of Air Staff, post-independence, and Air Chief Marshal. Fali Homi Major served as the 18th Chief of Air Staff. Vice Admiral RF Contractor served as the 17th Chief of the Indian Coast Guard. Lieutenant Colonel Ardeshir Burjorji Tarapore was killed in action in the 1965 Indo-Pakistan war and was posthumously awarded the Param Vir Chakra, India's highest military award for gallantry in action. Lieutenant General FN Bilimoria was a senior officer of the Indian Army and the father of Lord Karan Bilimoria, founder of the Cobra Beer company.

Particularly notable Parsis in other areas of achievement include cricketers Farokh Engineer and Polly Umrigar, rock star Freddie Mercury, composer Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji and conductor Zubin Mehta; cultural studies theorist Homi K. Bhabha; screenwriter and photographer Sooni Taraporevala; authors Rohinton Mistry, Firdaus Kanga, Bapsi Sidhwa, Ardashir Vakil and Pakistani investigative journalist Ardeshir Cowasjee; actor Boman Irani; educator Jamshed Bharucha, India's first woman photo-journalist Homai Vyarawalla; Actresses Nina Wadia, Sanaya Irani and Persis Khambatta are Parsi who appear primarily in Bollywood films and television serials. Naxalite leader and intellectual Kobad Ghandy is a Parsi. Dorab Patel was Pakistan's first Parsi Supreme Court Justice. Fali S Nariman is a constitutional expert and noted jurist. Soli Sorabjee is a prominent Indian jurist and former Attorney-General of India. Rattana Pestonji was a Parsi living in Thailand who helped develop Thai cinema. Another famous Parsi is the Indian-born American actor Erick Avari, best known for his roles in science-fiction films and television.

References

Citations

- (26 November 2014). "India's declining Parsi population". Al Jazeera.

- Dean Nelson. "India's dwindling Parsi population to be boosted with fertility clinics". The Telegraph.

- "Two decades from now, Pakistan will have no Parsis".

- Desmukh, Fahad (28 November 2012). "The Parsi Community in Karachi, Pakistan". Public Radio International.

- Hodivala 1920, p. 88.

- Boyce 2001, p. 148.

- Lambton 1981, p. 205.

- Nigosian 1993, p. 42.

- Khanbaghi 2006, p. 17.

- Jackson 1906, p. 27

- Bleeker & Widengren 1971, p. 212

- Akram, A. I.; al-Mehri, A. B. (September 1, 2009). The Muslim Conquest of Persia. Maktabah Publications. ISBN 9780954866532.

- PARSI COMMUNITIES i. EARLY HISTORY – Encyclopaedia Iranica. Iranicaonline.org (2008-07-20). Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- Parsee, n. and adj. - Oxford English Dictionary. oed.com. Retrieved on 2015-03-03.

- Ganesh, Kamala (2008). "Intra-community Dissent and Dialogue: The Bombay Parsis and the Zoroastrian Diaspora". Sociological Bulletin. 57 (3): 315–336. doi:10.1177/0038022920080301. JSTOR 23620804. S2CID 148248437.

- Pavan K. Varma (2007). The Great Indian Middle class. Penguin Books. p. 28. ISBN 9780143103257.

...its main adherents came from those in government service, qualified professionals such as doctors, engineers and lawyers, business entrepreneurs, teachers in schools in the bigger cities and in the institutes of higher education, journalists [etc]...The upper castes dominated the Indian middle class. Prominent among its members were Punjabi Khatris, Kashmiri Pandits and South Indian brahmins. Then there were the 'traditional urban-oriented professional castes such as the Nagars of Gujarat, the Chitpawans and the Ckps (Chandrasenya Kayastha Prabhus)s of Maharashtra and the Kayasthas of North India. Also included were the old elite groups that emerged during the colonial rule: the Probasi and the Bhadralok Bengalis, the Parsis and the upper crusts of Muslim and Christian communities. Education was a common thread that bound together this pan Indian elite... But almost all its members spoke and wrote English and had had some education beyond school

- "Social Action, Volume 50". Indian Social Institute. 2000: 72. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "D.L. Sheth".

- Parsi (people) - Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- Parsi legend attributes it to a Hindu author; cf. Paymaster 1954, p. 8 incorrectly attributes the text to a Zoroastrian priest

- Stausberg 2002, p. I.373.

- Boyce 2002, p. 105.

- Stausberg 2002, p. I. 373.

- Jamshed Irani v. Banu Irani (1966) 68 Bom. L.R. 794

- Qamar et al. 2002, p. 1119.

- Quintana-Murci et al. 2004, p. 840.

- Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Ayub, Qasim; Rai, Niraj; Prakash, Satya; Mushrif-Tripathy, Veena; Mezzavilla, Massimo; Pathak, Ajai Kumar; Tamang, Rakesh; Firasat, Sadaf; Reidla, Maere; Karmin, Monika; Rani, Deepa Selvi; Reddy, Alla G.; Parik, Jüri; Metspalu, Ene; Rootsi, Siiri; Dalal, Kurush; Khaliq, Shagufta; Mehdi, Syed Qasim; Singh, Lalji; Metspalu, Mait; Kivisild, Toomas; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Villems, Richard; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy (2017). ""Like sugar in milk": Reconstructing the genetic history of the Parsi population". Genome Biology. 18 (1): 110. doi:10.1186/s13059-017-1244-9. PMC 5470188. PMID 28615043.

- Sir Dinsha Manekji Petit v. Sir Jamsetji Jijibhai 1909.

- Sarwar Merwan Yezdiar v. Merwan Rashid Yezdiar 1948.

- Merwan Rashid Yezdiar v. Sarwar Merwan Yezdiar 1950.

- Jamshed Irani v. Banu Irani 1966.

- Chaubey G, Ayub Q, Rai N, Prakash S, Mushrif-Tripathy V, Mezzavilla M, et al. (2017). ""Like sugar in milk": reconstructing the genetic history of the Parsi population". Genome Biol. 18 (1): 110. doi:10.1186/s13059-017-1244-9. PMC 5470188. PMID 28615043.

- "Where we belong: The fight of Parsi women in interfaith marriages". October 24, 2017.

- "Parsi population dips by 22 per cent between 2001-2011: study". The Hindu. July 25, 2016.

- Roy & Unisa 2004, pp. 8, 21.

- Taraporevala 2000, p. 9.

- Roy & Unisa 2004, p. 21.

- Roy & Unisa 2004, p. 14.

- "Saving India's Parsis". BBC.

- Roy & Unisa 2004, pp. 18, 19.

- Hodivala 1920.

- Vimadalal 1979, p. 2.

- Paymaster 1954.

- Taraporevala 2000.

- Kulke 1978, p. 25.

- Stausberg 2002, p. I.374.

- John R. Hinnells (April 28, 2005). The Zoroastrian Diaspora:Religion and Migration: Religion and Migration. OUP Oxford. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-19-826759-1.

- Maneck 1997, p. 15.

- Paymaster 1954, pp. 2–3.

- Dhalla 1938, p. 447.

- Kulke 1978, p. 29.

- Dhalla 1938, p. 448.

- Dhalla 1938, p. 457.

- Dhalla 1938, pp. 474–475.

- Dhalla 1938, p. 474.

- Palsetia 2001, pp. 47–57.

- Luhrmann 2002, p. 861.

- Luhrmann 1994, p. 333.

- Darukhanawala & Jeejeebhoy 1938, p. 33.

- White 1991, p. 304.

- Palsetia, Jesse S. (2001). The Parsis of India : preservation of identity in Bombay City. Leiden ; Boston ; Köln: Brill. pp. 53–56. ISBN 9789004121140.

- Hull 1913.

- Palsetia 2001, pp. 37–45, 62-64, 128-140, 334-135.

- White 1991, p. 312.

- Ovington 1929, p. 216.

- Karaka 1884, pp. 215–217.

- Dobbin 1970, pp. 150–151.

- Palsetia 2001, pp. 223–225.

- Palsetia 2001, pp. 135–139.

- Dhalla 1948, p. 483.

- Karaka, Dosabhai Framji (1884). History of the Parsis. 1. London: Macmillian and Co. pp. 91–93. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Ralhan 2002, p. 1101.

- "Asia and the Americas". Asia and the Americas. Asia Press. 46: 212. 1946.

Many Muslim organizations are opposed to it. Every non-Muslim, whether he is a Hindu or Sikh or Christian or Parsi, is opposed to it. Essentially the sentiment in favor of partition has grown in the areas where Muslims are in a small minority, areas which, in any event, would remain undetached from the rest of India. Muslims in provinces where they are in a majority have been less influenced by it; naturally, for they can stand on their own feet and have no reason to fear other groups. It is least evident in the Northwest Frontier Province (95 per cent Muslim) where the Pathans are brave and self-reliant and have no fear complex. Thus, oddly enough, the Muslim League's proposal to partition India finds far less response in the Muslim areas sought to be partitioned than in the Muslim minority areas which are unaffected by it.

- Cellular and humoral immunodepression in vultures feeding upon medicated livestock carrion. Rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- News Release. The Peregrine Fund (2012-08-23). Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- Tower of Silence, Karachi

- Quintana-Murci, Lluís; Chaix, Raphaëlle; Wells, R. Spencer; Behar, Doron M.; Sayar, Hamid; Scozzari, Rosaria; Rengo, Chiara; Al-Zahery, Nadia; Semino, Ornella (2004). "Where West Meets East: The Complex mtDNA Landscape of the Southwest and Central Asian Corridor". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 827–845. doi:10.1086/383236. PMC 1181978. PMID 15077202.

- Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Ayub, Qasim; Rai, Niraj; Prakash, Satya; Mushrif-Tripathy, Veena; Mezzavilla, Massimo; Pathak, Ajai Kumar; Tamang, Rakesh; Firasat, Sadaf (June 14, 2017). ""Like sugar in milk": reconstructing the genetic history of the Parsi population". Genome Biology. 18 (1): 110. doi:10.1186/s13059-017-1244-9. ISSN 1474-760X. PMC 5470188. PMID 28615043.

- "High rate of cancer puts Parsis under microscope". The Independent. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- Dhavendra Kumar (September 15, 2012). Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-2231-9.

- Can Zoroastrians save their faith?. Parsi Khabar (2010-01-06). Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- Rivetna 2002.

- JAMSHEDJI TATA Founder of TATA Industries

Sources

- "Parsi-Religion and Expressive Culture". Countries and their Cultures. Advameg, Inc.

- "A brief introduction to Zoroastrianism". Kwintessentials. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- Baird, Robert (2009). Religion in Modern India (4th ed.). New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors.

- Boyce, M. (1970), "On the Calendar of the Zoroastrian Feasts", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 33 (3): 513–539, doi:10.1017/S0041977X00126540, JSTOR 614520

- Boyce, M. (July 2002), "The Parthians", in Godrej, P.J. (ed.), A Zoroastrian Tapestry, New York: Mapin, ISBN 978-1-890206-22-2

- Darukhanawala, H.; Jeejeebhoy, J (1938), Parsi Lustre on Indian Soil, Vol. I, Bombay: G. Claridge

- Dhalla, M. (1938), History of Zoroastrianism, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-404-12806-7

- Dobbin, C. (1970), "The Parsi Panchayat in Bombay City in the Nineteenth Century", Modern Asian Studies, 4 (2): 149–164, doi:10.1017/S0026749X00005102, JSTOR 311609

- Eliade, M.; Couliano, I.; Wiesner, H. (1991), The Eliade Guide to World Religions, New York: Harper Collins, ISBN 978-0-06-062145-2

- Hinnells, John R. (2005), The Zoroastrian Diaspora: Religion and Migration, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-826759-1

- Hodivala, S. (1920), Studies in Parsi History, Bombay

- Hull, E. (1913), "Parsis", Catholic Encyclopaedia, 11, New York: Robert Appleton Company

- Jamshed Irani v. Banu Irani (1966), 68 blr 794, Justice Mody

- Karaka, D. F. (1884), History of the Parsis: Including Their Manners, Customs, Religion, and Present Position, 1, London: Macmillan and Co

- Kulke, E. (1978), The Parsees in India: A Minority as Agent of Social Change (2nd ed.), New Delhi: Vikas Pub. House

- Luhrmann, T.M. (June 1994), "The Good Parsi: The Postcolonial 'Feminization' of a Colonial Elite", Man, 29 (2): 333–357, doi:10.2307/2804477, JSTOR 2804477

- Luhrmann, Tanya M. (August 2002), "Evil in the Sands of Time: Theology and Identity Politics among the Zoroastrian Parsis", The Journal of Asian Studies, 61 (3): 861–889, doi:10.2307/3096349, ISSN 0021-9118, JSTOR 3096349, S2CID 163092265

- Maneck, Susan Stiles (1997), The Death of Ahriman: Culture, Identity, and Theological Change Among the Parsis of India, Bombay: K.R. Cama Oriental Institute

- Nanavutty, P. (1970), The Parsis, New Delhi: National Book Trust

- Ovington, J. (1929), Rawlinson, H.G. (ed.), A Voyage to Surat in the Year 1689, London: Humphrey Milford, ISBN 978-81-206-0945-7

- Palsetia, Jesse S. (2001), The Parsis of India, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-12114-0.

- Parsiana (February 2006), "How trust-worthy?", Parsiana (48)

- Paymaster, R. (1954), Early History of the Parsees in India, Bombay: Zarthoshti Dharam Sambandhi

- Sir Dinsha Manekji Petit v. Sir Jamsetji Jijibhai (1909), 33 ILR 509 and 11 BLR 85, Justices Dinshaw Davar and Frank Beaman

- Qamar, R.; Ayub, Q.; Mohyuddin, A.; Helgason, A.; Mazhar, Kehkashan; Mansoor, Atika; Zerjal, Tatiana; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Mehdi, S. Qasim (2002), "Y-chromosomal DNA variation in Pakistan", American Journal of Human Genetics, 70 (5): 1107–1124, doi:10.1086/339929, PMC 447589, PMID 11898125

- Quintana-Murci, L.; Chaix, Raphaëlle; Wells, R. Spencer; Behar, Doron M.; Sayar, Hamid; Scozzari, Rosaria; Rengo, Chiara; Al-Zahery, Nadia; et al. (May 2004), "Where West Meets East: The Complex mtDNA Landscape of the Southwest and Central Asian Corridor", American Journal of Human Genetics, 74 (5): 827–845, doi:10.1086/383236, PMC 1181978, PMID 15077202, archived from the original on May 9, 2008

- Ralhan, Om Prakash (2002), "Indian National Congress", Encyclopaedia of Political Parties, New Delhi: Anmol Publications, ISBN 978-81-7488-865-5.

- Random House (1993), "Parsi", Random House Unabridged Dictionary (2nd ed.), New York: Random House

- Rivetna, Roshan, ed. (2002), The Legacy of Zarathushtra: An Introduction to the Religion, History and Culture of the Zarathushtis, Hinsdale: Federation of the Zoroastrian Associations of North America

- Roy, T.K.; Unisa, S.; Bhatt, M. (2004), Growth of the Parsi population in India, Mumbai: National Commission for Minorities, archived from the original on November 8, 2006

- Stausberg, M. (2002). Die Religion Zarathushtras (in German). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag.

- Taraporevala, S. (2000), Zoroastrians of India. Parsis: A Photographic Journey, Bombay: Good Books, ISBN 978-81-901216-0-6, archived from the original on February 14, 2006, retrieved February 21, 2006

- White, D. (May 1991), "From Crisis to Community Definition:The Dynamics of Eighteenth-Century Parsi Philanthropy", Modern Asian Studies, 25 (2): 303–320, doi:10.1017/S0026749X00010696, JSTOR 312514

- Sarwar Merwan Yezdiar v. Merwan Rashid Yezdiar (1948), Parsi Matrimonial Court, Justice Coyaji

- Merwan Rashid Yezdiar v. Sarwar Merwan Yezdiar (1950), 52 blr 876, Justices Chagla and Gajendragadkar

Further reading

- Naoroji, Dadabhai (1861), The Parsee Religion, University of London

- Haug, Martin. (1878) Essays on the Sacred Language, Writings, and Religion of the Parsis

- Karaka, Dosabhai Framjee (1884), History of the Parsis – Including their manners, customs, religion and present position. (Vol. 1), Macmillan & Co., London

- Karaka, Dosabhai Framjee (1884), History of the Parsis – Including their manners, customs, religion and present position. (Vol. 2), Macmillan & Co., London

- Karkaria, Bachi (January 9, 2016). "Why is India's wealthy Parsi community vanishing?". BBC.

- Marashi, Afshin. "Exile and the Nation: The Parsi Community of India and the Making of Modern Iran". University of Texas Press, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parsi. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Parsis |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Parsees. |

- Parsis at Curlie

- "Govt launches scheme to arrest decline in Parsi population". Hindustan Times. July 27, 2010. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011.

- Parsis – a photographic journey—online book

- "Falling Indian minority hopes romance can stop decline"—BBC News

- The Story of Parsi Enterprise