Bahay na bato

Bahay na bato (Tagalog, literally "house of stone") is a type of building originating during the Philippines' Spanish Colonial period. It is an updated version of the traditional bahay kubo. Its design has evolved throughout the ages, but still maintains the bahay kubo's architectural basis which corresponds to the tropical climate, stormy season, and earthquake-prone environment of the whole archipelago of the Philippines and fuses it with the influence of Spanish colonizers and Chinese traders. Thus created was a hybrid of Austronesian, Spanish, and Chinese architecture with American influence during the American era, supporting the fact that the Philippines is a result of these cultures mixing together. Its most common appearance is that of an elevated, overhanging wooden upper-story nipa hut (with balustrades, ventanillas, and capiz shell sliding windows) that stands on Spanish-style solid stone blocks or bricks and posts as foundation instead of just wood, bamboo stilts, or timber posts. Roofing is either Chinese tiled roof or thatch (nipa, sago palm, or cogon), of which many today are being replaced by galvanized or other modern roofing. It followed the bahay kubo's arrangements such as open ventilation and elevated apartments used as living space with the ground floor used for storerooms, cellars, and other business purposes. Like bahay kubo, much of this ground level was reserved for storage; in business districts, some spaces were rented to shops. Horses for carriages were housed in stables called caballerizas.[1] Bahay na bato had a rectangular plan that reflected vernacular Austronesian Filipino traditional houses integrated with Spanish style.[2]

It was popular among the elite or middle-class, and integrated the characteristics of the nipa hut with the style, culture and technology of Chinese and Spanish architecture. The 19th century was the golden age of these houses, when wealthy Filipinos built fine houses all over the archipelago.

The same architectural style was used for Philippines' Spanish-era convents, monasteries, schools, hotels, factories, and hospitals, and with some of the American-era Gabaldon school buildings, all with few adjustments.[3] This architecture is still used during the American colonization of the Philippines. After the Second World War, building these houses declined and eventually stopped in favor of post-World War II modern architecture.

Today, these houses are more commonly called ancestral houses, due to most ancestral houses in the Philippines being of bahay na bato architecture.

Etymology

Though the Filipino term bahay na bato means "house of stone", these houses are not fully made up of stone; some are even dominated more by wooden materials, and some more modern ones use concrete materials. The name got applied to the architecture as generations pass by, because contrary to its predecessor bahay kubo, which are fully made of organic materials, it uses stone materials.[3]

History

Precolonial Philippine architecture is based on the traditional stilt houses of the Austronesian people of Southeast Asia. The first buildings during the early years of Spanish occupation were of wood and bamboo, materials with which the pre-Hispanic indigenous Filipinos had been working expertly since early times known as bahay kubo (later named by the Americans as "nipa hut"). Bahay kubo's roofs were of nipa palm or cogon grass. In its most basic form, the house consisted of four walls enclosing one or more rooms, with the whole structure raised above ground on stilts. Its resemblance to a cube earned its description in Spanish, cubo. Clusters of these wooden houses clearly were predisposed to fire.[3]

The Spaniards then quickly introduced the idea of building more permanent communities with the church and government center as a focal points. By the mid-1580s, through the efforts of Domingo Salazar, the first bishop of Manila, and of the Jesuit Antonio Sedeño, edifices began to be constructed of stone. Fr. Sedeño built the first stone building, which was the residence of Bishop Salazar. By 1587, Governor General Santiago de Vera required all buildings in Manila to be built of stone. For this purpose, the Chinese and the indigenous Filipinos were taught how to quarry and dress stone, how to prepare and use mortar, and how to mold bricks. Thus began what has been called the first golden age of building in stone. This new community setup made construction using heavier, more permanent materials desirable. Some of these materials included bricks, mortar, tiles and stone. Glowing accounts of towering palaces and splendid mansions reached the peninsula. However, the ambitious plans of the Spaniards were dashed in 1645 when a terrible earthquake struck Manila.[3]

The twin dangers of fire and earthquake gave rise to another type of architecture. Finding European construction styles impractical in local conditions, Spanish and Filipino builders quickly adapted the characteristics of the bahay kubo of the natives and applied it to Spanish Colonial architecture. This type of construction was soon called bahay na bato or as Jesuit Ignacio Alzina calls it, "arquitectura mestiza" or “mixed architecture”.[3]

Under more than three centuries of Spanish initiative, buildings of wood, stone, and brick were constructed all over the archipelago, from the Batanes Islands in the north to Tawi-Tawi in the south, from Palawan in the west to Samar in the east.[3]

During the Second World War, many of these houses were destroyed by both the American and Japanese forces.

Styles

Different styles depend on each house's individual appearance. For example, some Bahay na bato do not have ventanillas, some do not have Capiz windows, and some lack both. Some have galvanized roofs, some have tiled roofs, and some have nipa or cogon roofs. First-level walls may be made of bricks, adobe stones, or coral stones; more modern structures uses concrete or wood. Although retaining the basic form, the 19th-century bahay na bato reflected changing tastes through the incorporation of motifs from the prevalent styles.

Houses like the Vega Ancestral House that have almost fully wooden materials even to the first level walls are still considered Bahay na bato; the name Bahay na bato was applied to this architecture as generations passed by, as most of these houses use stone materials, contrary to the precolonial era that used no stones at all. The same principle applies to the nipa hut – not all nipa huts use nipa materials; some use cogon. Its local name, bahay kubo, means "cube house", though not all are of a cubic shape.[3]

These houses have an unprecedented mixing and matching of architectural styles, such that a Bahay na bato can have Neogothic and Neo-Mudejar (Neo-Moorish) details in the same corners — that is, on top of the Baroque (which may be of a particular style, e.g. the spare-by-comparison Viennese Secessionist style). These quaint mixes give the Bahay na bato an architectural style that evolved from both East and West, and thus makes it truly Filipino, as it corresponds to Philippine history of being a melting pot of east and west.[4] Although retaining the basic form, the 19th-century bahay na bato reflected changing tastes through the incorporation of motifs from the prevalent styles such as Victorian. Neoclassical decorations included columns, pilaster, caryatids, Atlases and friezes adopted from Greek and Roman architecture. The dawn of Art Nouveau era also has a big influence on the mixing of styles and aesthetics of these houses. Many latter Bahay na bato adapted the modernist designs such as Art Deco during Art Deco era and the shortly, Post-War Modernist designs, many of which was only a product of loosely restored Bahay na bato after the war that eventually led to its decline.[3] Style may also vary by area. Each region evolved its own building style, which were in many cases dependent on the materials available. As construction techniques were developed, quarries opened, and kilns constructed, various parts of the country began to show a preference for specific building materials.[3] As a result, Bahay na bato has several variations along ethnic lines. The Bahay na bato in Cebu, for example, differs from the one in Samar.

The Ivatans in Batanes, however, have a very different Bahay na bato called Sinadumparan. This house is Native Ivatan architecture in principle, adopted to Philippine' Spanish colonial construction technology. Sinadumparan's main house, Rakuh, is very similar to the traditional Bahay na bato on the mainland. and has a crossbred appearance between Ivatan traditional house'and Bahay na bato from the mainland.

Examples of regional variants:

Metro Manila

Manila, the capital of the Philippines, has one of the most diverse style of Bahay na bato, ranging from the early period of Spanish colonization to the American era. Many were destroyed by World War II. However, the Metro Manila area still has one of the largest concentration of Bahay na Bato houses.[3] Most of the buildings in Manila and Central Luzon were of adobe, a volcanic tuff quarried from the hills which is entirely different from the material of the same name found in Latin America (adobe in those Hispanic countries refers to mud and straw formed into rectangular blocks which are then dried in the sun).[3]

The largest, fanciest, and most prestigious companies were eventually established along a nearby street called the Escolta; by the second half of the 19th century this was the most important commercial district in the country. The opening of Manila as a free port encouraged British, Germans, French, and other foreigners to set up businesses on the Escolta and adjacent streets, and the majestic Bahay na Bato buildings were built.[3]

Inside the old walled city of Intramuros

Inside the old walled city of Intramuros Casa Manila

Casa Manila Kapitan Moy Ancestral house in Marikina

Kapitan Moy Ancestral house in Marikina

Northern Luzon

Edralin Ancestral house House has the typical wooden upper half and solid lower half of many Bahay na bato in the Philippines except the lower half is made with bricks typical to Ilocos

Edralin Ancestral house House has the typical wooden upper half and solid lower half of many Bahay na bato in the Philippines except the lower half is made with bricks typical to Ilocos Cariño ancestral house in Candon, Ilocos Sur

Cariño ancestral house in Candon, Ilocos Sur

The Northern region have some of the best preserved Bahay na bato in the whole of Philippines. The unique style of the north, commonly in the Ilocos Region, usually bases its design on brick materials, common in Bahay na bato, churches and other constructed buildings, walls, monuments and fortification of the area.[3]

Brick was the essential building material in northern Luzon; houses and churches of brick were also built in scattered areas of the Archipelago, all the way down to Jolo, Sulu.[3] Unique designs of the north may include having the facade walls of the second level made up of stone material in many buildings, rather than the more common wooden second level facade. However, it still remains faithful to the Nipa hut principle. These non-wooden (stone) second level facade walls style are also present in some of the Bahay na bato of other regions besides the north, like the 1730 Jesuit house of Cebu in Visayas.[3] The wooden second level facade Bahay na bato are still present in the North.[3]

In Vigan, capital of Ilocos Sur, many home owners chose to build both stories in brick, which was available in large quantities. With the massive walls, the volada disappeared in many residences and the kitchen became an extension in stone, with vents piercing the walls to let out smoke.

Calabarzon

Calabarzon is a region with some of the best preserved heritage houses. Towns along the coasts of Luzon, especially in Batangas, used roughly hewn blocks of coral and Adobe stone.[3]

Marcela Agoncillo house

Marcela Agoncillo house Taal Batangas old house

Taal Batangas old house Felipe Agoncillo House

Felipe Agoncillo House Cuenca Ancestral house

Cuenca Ancestral house

Central Luzon

The Bahay na bato in Bulacan and many in Central Luzon are famous for their carvings. The most famous ones are in the Malolos, in its heritage core where ancestral houses are located.[3] Since adobe lends itself to sculpture, houses in Bulacan had facades decorated with carved flowers, leaves, and religious symbols.[3]

Bicol

Many constructions in the Bicol peninsula took advantage of the abundant volcanic stone.[3]

Juban Sorosogon

Juban Sorosogon

Visayas

Panares Ancestral house

Panares Ancestral house Yap-Sandiego Ancestral house

Yap-Sandiego Ancestral house

Most Bahay na batos' foundations in Visayas are coral stone material though many are still adobe and bricks. Cebu, Bohol, Negros and Iloilo are famous for their Bahay na bato houses.[3] Throughout the Visayas, the craft of cutting stone or coral was virtually elevated into a fine art, with blocks fitting so precisely into each other that not even a razor blade could be inserted between blocks. The material was so durable that it did not have to be protected with a layer of paletada. This art was brought by the Visayan settlers to the coastal towns of Mindanao.[3]

Batanes

Ivatan people of Batanes have a very different style of Bahay na bato. They are called Sinadumparan. As the islands of Batanes was absorbed to the colonial nation the Philippines much later through Spanish conquest, the Sinadumparan was developed much laters as well. Combining Pre-colonial Ivatan style and Colonial Filipino style (Bahay na bato). Sinadumpraran house has two buildings; One is kitchen and Another is the living area building called Rakuh. The Filipino colonial style (Bahay na bato) influence is very evident in the Rakuh building.

Other buildings

Many convents, monasteries, schools, hospitals, offices, stations, etc. also adapted the Bahay Kubo architecture to the Spanish colonial style. As a result, many of these buildings ends up being a Bahay na bato as well, with very few differences such as size and proportion.

Examples of such buildings include the University of Santo Tomas (Intramuros), Colegio de Santa Rosa Manila, San Juan De Dios Hospital, Tutuban Station, AMOSUP hospital, Hotel de Oriente in Binondo, Malacañan Palace and many other church convents which are still standing today.[3]

Examples:

.jpg.webp) Malacañang Palace (Philippine president's palace)

Malacañang Palace (Philippine president's palace)

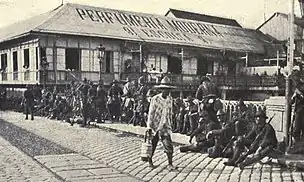

Tutuban Train Station, 1890s

Tutuban Train Station, 1890s Old San Juan De Letran

Old San Juan De Letran

.jpg.webp) Zamboanga City hall

Zamboanga City hall El Amanecer Building

El Amanecer Building Hotel De Oriente

Hotel De Oriente Museo De Loboc/Convent

Museo De Loboc/Convent Taal, Batangas Convent

Taal, Batangas Convent

Parts of Bahay na bato

Facade with volada, ventanilla and capiz window

Facade with volada, ventanilla and capiz windowJust like any other architectures, different features of Bahay na bato varies depending on each individual buildings, which would mean some houses would lack or have some of these features than the others:

- Accessoria – Apartment-type dwelling characterized by common party walls shared by adjoining units with a separate door in front of each

- Aljibe – Cistern

- Antesal – Caida

- Aparador de tres lunas – Armoire with three sections

- Arko – Arch

- Azotea – Open-air balcony beside the kitchen that housed a cistern (aljibe) and the bathroom, and was usually a work area

- Atlas, Atlantes – A column,pilaster and other decorative features in the shape of a man

- Balconaje, Balcon – Balcony

- Banggera – A wooden dish rack that extends outside the kitchen window. After the dishes are washed, they are placed here to be air-dried. The inverted cups are placed on the ends of the wooden sticks and the plates are placed in between or above the slats. On the far left is a tapayan/banga, an earthenware jar that keeps water cool.

- Bañera – Bathtub

- Baño – Bathroom

- Barandillas – railing or balustrade (usually wooden)

- Barrigones – "Buntis" (or bombere, pregnant) grillworks on windows, to accommodate planters

- Batalan – Rear part of house used for washing and water storage, with a flooring often made of slatted bamboo; more a part of a bahay kubo (but may be present as well at the rear of a bahay na bato)

- Baul mond – Traveling trunk

- Bentwood beech chairs and other furniture – Imported dark wood furniture

- Brackets – Series of often diagonal braces placed in support of the volada on the second floor

- Butaka – A version of silla perezosa with no leg rests

- Caida – Landing on the upper entrance hall; foyer of the second floor; also called "antesala"

- Calado – Lace-style fretwork or latticework used to adorn room dividers and to allow air to circulate

- Capilla – Long bench, a staple item in the caida

- Capital – Topmost member of a column (or pilaster) mediating between the column and the load"

- Capiz Windows – (Often) sliding window made of capiz shells cut into squares

Bahay na Bato interiorCaryatid – A sculpted female figure serving as an architectural support taking the place of a Pilaster, column or a pillar etc. supporting an entablature on her head

Bahay na Bato interiorCaryatid – A sculpted female figure serving as an architectural support taking the place of a Pilaster, column or a pillar etc. supporting an entablature on her head kama or Bed

kama or Bed- Clerestory – Any high windows above eye level for the purpose of bringing outside light, fresh air, or both into the inner space

- Cocina – Kitchen, which was typically built separately from the house

- Colonette – A small, thin decorative column supporting a beam (horizontal timber) or lintel (beam spanning a door or window)

- Comedor – Dining room

- Comun – Toilet; also called "latrina"

- Corbel – A projection jutting out from a wall to support a structure above it; also "braces"

- Cornice – A ledge or generally any horizontal decorative molding that crowns a building or furniture element

- Court, courtyard – A space enclosed by walls and is open to the sky; has azotea or balconaje

- Cuartos – Rooms

- Cuatro aguas – Hip roof, which has more corners and angles, making it stronger than the dos aguas (gable) or high-pitched roof due to stronger aerodynamics (i.e., more wind resistance); also has the advantage of providing an overhang, which is effective for protecting the house from rainwater and from direct sunlight

- Dapugan – A platform in the kitchen where the kalan or clay stove is placed

- Despacho – Office; also "oficina"

- Dispensa – Pantry

- Dos aguas – Gable or high-pitched roof

- Dougong – A simplified and localized Filipino version of the ones in China. Chinese neighboring cultures evolved different variation and localized versions of this, one such example aside from Filipino Dougong is the Japanese Tokyō Brackets.

- Eave – Bottom edge of a roof

- Engaged column – Column in support of the roof above

- Entresuelo – Mezzanine; literally meaning "between floors", this is the area where clients, tenants or estate managers (if the owner was a rich landowner) wait before being admitted to the oficina (office)

- Escalera – Stairway

- Escritorio – A large chest of drawers, commonly adorned with inlay work

- Estante – Dining room cabinet where chinaware and silverware are displayed

- Facade – Front

- Finial – A usually foliated ornament forming an upper extremity

- Fresquera – Storage room for salted food, etc.; placed on the wall of the house facing outside

- Gable – The part of a wall that encloses the end of a pitched roof

Stair

Stair Sala

Sala - Gallinera – Literally, "chicken seat"; "usually found outside the oficina of a landowner; coming from the Spanish word 'gallo' (chicken), this church bench-inspired settee is used for farmers to place chickens on the cage underneath in exchange for paying cash" (Old Manila Nostalgia blog)

- Gargoyle – A carved stone grotesque with a spout designed to convey water from a roof and away from the side of a building, thereby preventing rainwater from running down masonry walls and eroding the mortar between

- Gingerbread trim, running trim – 19th century Victorian style of fancifully cut and pierced frieze boards, scrolled brackets, sawn balusters, and braced arches, to transform simple frame cottages into one-of-a-kind homes; usually attached to the eaves to make it more decorative and to curving iron rods that help support the media agua

- Kama – Four-poster bed

- Kama ni Ah Tay – A once popular signature four-poster bed design that was carved by a famous Chinese furniture maker named Eduardo Ah Tay. To have this bed was considered a symbol of status during the Spanish era.[5]

- Kantoneras (brackets) – Either plain calado cut-outs or fully carved embellishments usually placed where beams and columns intersect especially under the soffit or overhanging ceiling outside house; also seen to decorate door or window openings, hallways or simply dividing spaces

Zaguan

Zaguan - Lansenas – Kitchen sideboards

- Latrina – Comun

- Load-bearing wall – Wall used in place of posts to bear weight

- Machuca tiles (formerly known as "baldozas mosaicas") – colorful Mediterranean-style cement tiles used for the zaguan flooring, often in harlequin pattern; manufactured by the Machuca company; another brand is Majolica

- Mascaron – An architectural ornament representing a face or head, human or animal, that is often grotesque or frightening

- Media aguas – Canopy or roof shed, consisting of a piece of metal roof that protects the window from rain or heat; not to be confused with awning

- Mirador – Lighthouse; lookout tower

- Moulding, molding – A strip of material (such as wood or metal) with some design or pattern that is used as a decoration on a wall, on the edge of a table, etc.

- Oratorio – Prayer room with an altar of santos

- Painted metal sheet ceiling – Pressed tin or copper ceiling from maybe late Victorian to early American colonial period, to prevent decay by moisture or worms (or even mouse)

Old containers

Old containers - Paminggalan – A cabinet where leftover food and preserves are stored. The doors of the cabinet have slats so that it can absorb air and room temperature inside. To avoid ants from coming up and getting to the food, the legs of the cabinet are placed on containers filled with kerosene or any liquid.

- Pasamano – Window ledge

- Persiana – Louver window

- Piedra china – Chinese stone used to pave the floor of the zaguan

- Pilaster – False pillar used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function

- Platera – Aparador or cabinet for kitchenware (chiefly china)

- Porte cochere – Horse carriage porch or portico at the main entrance

- Portico – "(From Italian) a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls"

- Puerta – "Door of the entrada principal (main entrance)"

- Puertita – "small cut door that is part of the puerta"

- Pugon – Clay oven

- Punkah – Ceiling cloth fan

- Sala mayor – Main living room, place for late-afternoon parties called tertulias and dances called bailes

- Sala menor – Secondary living room

- Sillas Americanas – "American chairs, considered the Monobloc chairs of their time (due to ubiquity)"

- Silla perezosa – Lazy chair

- Solihiya – Typical wicker weave pattern in furniture

- Stained glass – "Glass colored or stained (as by fusing metallic oxides into it) for decorative applications (as in windows)"

- Transom – "Transverse horizontal structural beam or bar" often in floral tracery design

- Trompe-l'œil – "A style of painting in which things are painted in a way that makes them look like real objects"

- Tumba-tumba – Philippine rocking chair

- Tympanum – triangular decorative wall surface over an entrance, door or window

- Valance – "A length of decorative drapery hung above a window to screen the curtain fittings"

- Ventana – "Wooden window panel that uses a grid pattern with flattened Capiz shell pane"; often in sliding style, as opposed to flinging out

Some Bahay na Bato are falling into abandonment.

Some Bahay na Bato are falling into abandonment. - Ventanilla – Literally 'small window'; "sliding panels between the floor and windows" to allow more air and light; "usually protected by balustrades which can either be wooden or wrought iron grills"

- Volada – "An enclosed overhanging balcony"; "a gallery (along the elaborate system of windows) which protects the rooms from the heat of the sun"

- Yerong pukpok – Gingerbread trim

- Zaguan – Ground floor (literally "passageway" in Arabic) to accommodate horse carriages and carrozas (processional carriages)[4]

See also

- History of the Philippines

- Culture of the Philippines

- Architecture of the Philippines

- Nipa hut

- Ancestral houses of the Philippines

- Earthquake Baroque

- Outline of classical architecture

- Rumah adat

- Rumah Melayu

- Spanish Colonial architecture

- Chinese architecture

- Sino-Portuguese architecture

- Shophouse

- Hanok

Citations

- http://nlpdl.nlp.gov.ph:81/CC01/NLP00VM052mcd/v2/v3.pdf Archived 2017-09-23 at the Wayback Machine The Spanish Colonial Tradition.

- Kim, Young Hoon; Lim, Sooyoung (2013). "A Study on the Spatial Composition influenced by climatic conditions in 19C Bahay na Bato around Cebu city in Philippines". Journal of the Korea Institute of Ecological Architecture and Environment. 13 (6): 29–37. doi:10.12813/kieae.2013.13.6.029.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- https://www.scribd.com/document/252360021/Bahay-Na-Bato Bahay na bato.

- http://filipiniana101.blogspot.com/2014/03/list-parts-of-bahay-na-bato.html List Parts of bahay na bato

- Old Manila Nostalgia blog

References

- Ahlborn, Richard. "Spanish-Philippine Churches: An Interpretation." Exchange News Quarterly (October–December 1958).

- ________. "The Spanish Churches of Central Luzon (I)." Philippine Studies, Vol. VIII (October 1960), 802–813.

- El Archipielago. Washington DC: Government Printing Press, 1900.

- Bañas, Raymundo C. A Brief Sketch of Philippine Catholic Churches. Manila: The Author, 1937.

- Castañeda, Dominador. Art in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines, 1964.

- "Christian Beginnings in Ilocandia." Ilocos Review, Vol. II, Nos. 1–2 (January December 1971).

- Cordero-Fernando, Gilda, ed. "The House With No Nails." In Turn of the Century. Manila: GCF Books, 1978.

- Coseteng, Alicia M.L. Spanish Churches in the Philippines. Manila: Mercury Press, 1972.

- Diaz-Trechuelo, Lourdes. Arquitectura Española en Filipinas (1565–1800). Sevilla: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos de Sevilla, 1959.

- Galende, Pedro. Angels in Stone: The Architecture of Augustinian Churches in the Philippines. Manila: C. Formoso Publishing, 1987.

- Gomez Piñol, Emilio. Aspectos generales de la relacion entre el arte Indo Portugues y el Hispano Filipino. Seminario de Historia de America: Universidad de Sevilla, 1973.

- Gonzales, Jose Ma. Labor evangelica y civilizadora de los religiosos Dominicos en Pangasinan (1587–1898). Manila: University of Santo Tomas Press, 1946.

- Gonzales, Julio. The Batanes Islands. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Press, 1969.

- Hargrove, Thomas R. "Submerged Spanish-Era Towns in Lake Taal, Philippines: An Underwater and Archival Investigation of a Legend." International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration, Vol. XV, No. 4 (1986): 323–337.

- Hargrove, Thomas R. The Mysteries of Taal. Manila: Bookmark Inc., 1991.

- Hornedo, Florentino H. "The Tumauini Church: Praise of Sublime Labor in Clay." Filipino Times, 23 February-1 March and 2–8 March 1987, 1, 5, 7 and 1, 6 respectively.

- Huerta, Felix de. Estado geografico, topografico, estadistico, historico-religioso de la santa y apostolica provincia de San Gregorio Magno. Manila: Imprenta de los Amigos del Pais, 1855.

- Javellana, Rene. Wood and Stone for God’s Greater Glory: Jesuit Art and Architecture in the Philippines. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1991.

- Jorde, Elviro P. Catalogo de los religiosos perteniente a la provincia del Smo. Nombre de Jesus de Filipinas desde su fundacion hasta nuestros dias. Manila: 1901.

- Jose, Regalado Trota. "How to Recognize Rococo Art." Art Collector (September 1984).

- ________. "Felix Roxas and the Gothicizing of Earthquake Baroque." 1030 Hidalgo. Vol. II. Manila: MARA Inc., 1986, 7–26.

- ________. Simbahan: Church Art in Colonial Philippines, 1565–1898. Makati: Ayala Museum, 1991.

- Kelemen, Pal. Baroque and Rococo in Latin America. 1st ed. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1951. 2nd ed. New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1967.

- ________. Art of the Americas—Ancient and Hispanic, with a Comparative Chapter on the Philippines. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1969.

- Kubler, George and Martin Soria. Art and Architecture in Spain and Portugal and their American Dominions 1500 to 1800. Great Britain: Penguin Books Ltd., 1959.

- Klassen, Winand. Architecture in the Philippines: Filipino Building in a Cross Cultural Context. Cebu City: University of San Carlos, 1986.

- Legarda, Benito F. "Angels in Clay: The Typical Cagayan Church Style." Filipinas Journal of Science and Culture, Vol. II. Makati: Filipinas Foundation, 1981.

- Lopez, Renato. "History of Santa Barbara in Pangasinan during the Spanish Time." Ilocos Review, Vol. XVI (1984): 75–133.

- Marco Dorta, Enrique. Arte en America y Filipinas Ars Hispaniae: Historia Universal del Arte Hispanico. 21 Madrid: Editorial Plus-Ultra, 1973.

- Merino, Luis. Arquitectura y urbanismo en el siglo XIX, estudios sobre el municipio de Manila. Vol. II. Manila: Centro Cultural de España and the Intramuros Administration, 1987.

- Mojares, Resil B. Casa Gorodo in Cebu—Urban Residence in a Philippine Province, 1860–1920. Cebu: Ramon Aboitiz Foundation Inc., 1983.

- Niño, Andres G. San Agustin of Manila. Manila: The Augustinian Monastery, 1975.

- Orlina, Paulina Gahol. Taal. n.d., 1976. Brochure.

- Pigafetta, Antonio. "First Voyage Around the World" (1525). In The Philippine Islands: 1493- 1898. Vol. XXXIII, 27-267. Edited by Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson. Cleveland, Ohio: A.H. Clark Co., 1903–1909. Reprinted, Mandaluyong, Rizal: Cacho Hermanos, 1973.

- Reed, Robert R. Colonial Manila. The Context of Hispanic Urbanism and Process of Morphogenesis. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

- Repetti, William C. Pictorial Records and Traces of the Society of Jesus in the Philippine Islands and Guam Prior to 1768. Manila: Manila Observatory, 1938.

- Roces, Alfredo R., ed. Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation. Vols. I-X. Manila: Lahing Pilipino Publishing Inc., 1977–1978.

- Rodriguez, Isacio R. The Augustinian Monastery of Intramuros. Translated by Pedro Galende. Makati: Colegio de San Agustin, 1976.

- Smith, Winfield Scott III, ed. Art of the Philippines, 1521–1957. Manila: The Art Association of the Philippines Inc., 1958.

- "Witnesses to Past Presences." Augustinian Mirror (April 1956), 41–58.

- Zialcita, Fernando N. and Martin I. Tinio Jr. Philippine Ancestral Houses 1810 1930. Quezon City: GCF Books, 1980.

- Zobel de Ayala, Fernando. Philippine Religious Imagery. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila, 1963.