Chinese architecture

Chinese architecture demonstrates an architectural style that developed over millennia in China, before spreading out to influence architecture throughout East Asia. Since the solidification of the style in the early imperial period, the structural principles of Chinese architecture have remained largely unchanged, the main changes being only the decorative details. Starting with the Tang dynasty, Chinese architecture has had a major influence on the architectural styles of Japan, Korea, Mongolia, and Vietnam, and a varying amount of influence on the architectural styles of Southeast and South Asia including Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and The Philippines.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8] Chinese architecture is typified by various features; such as, bilateral symmetry, use of enclosed open spaces, the incorporation of ideas related to feng shui such as directional hierarchies, a horizontal emphasis, and allusion to various cosmological, mythological, or other symbolism. Chinese architecture traditionally classifies structures according to type, ranging from pagodas to palaces. In part because of an emphasis on the use of wood, a relatively perishable material, and due to a de-emphasis on major monumental structures built of less-organic but more durable materials, much of the historical knowledge of Chinese architecture derives from surviving miniature models in ceramic and published planning diagrams and specifications. Some of the architecture of China shows the influence of other types or styles from outside of China, such as the influences on mosque structures originating in the Middle East. Although displaying certain unifying aspects, rather than being completely homogeneous, Chinese architecture has many types of variation based on status or affiliation, such as dependence on whether the structures were constructed for emperors, commoners, or used for religious purposes. Other variations in Chinese architecture are shown in the varying styles associated with different geographic regions and in ethnic architectural design.

The architecture of China is as old as Chinese civilization. From every source of information—literary, graphic, exemplary—there is strong evidence testifying to the fact that the Chinese have always enjoyed an indigenous system of construction that has retained its principal characteristics from prehistoric times to the present day. Over the vast area from Chinese Turkistan to Japan, from Manchuria to the northern half of French Indochina, the same system of construction is prevalent; and this was the area of Chinese cultural influence. That this system of construction could perpetuate itself for more than four thousand years over such a vast territory and still remain a living architecture, retaining its principal characteristics in spite of repeated foreign invasions—military, intellectual, and spiritual—is a phenomenon comparable only to the continuity of the civilization of which it is an integral part.

Throughout the 20th century, Chinese architects have attempted to combine traditional Chinese designs into modern architecture (usually government), with great success. Moreover, the pressure for urban development throughout contemporary China required higher speed of construction and higher floor area ratio, which means that in the great cities the demand for traditional Chinese buildings, which are normally less than 3 levels, has declined in favor of modern architecture. However, the traditional skills of Chinese architecture, including major and minor carpentry, masonry, and stonemasonry, are still applied to the construction of vernacular architecture in the vast rural area in China.

History

Neolithic and early antiquity

Chinese civilizational cultures developed in the plains along the numerous rivers that emptied into the Bohai and Hongzhow bays. The most prominent of these rivers, the Yellow and the Yangtze, hosted a complex fabric of villages. The climate was warmer and more humid than today, allowing for millet to be grown in the north and rice in the south. There was, however, no single "origin" of the Chinese civilization. Instead, there was a gradual multinuclear development between the years 4000 and 2000 BC – from village communities to what anthropologists call cultures to small but well-organized states. 2 of the more important cultures were the Hongshan culture (4700–2900 BC) to the north of Bohai Bay in Inner Mongolia and Hebei Province and the contemporaneous Yangshao culture (5000–3000 BC) in Henan Province. Between the 2, and developing later, was the Longshan culture (3000–2000 BC) in the central and lower Yellow River valley. These combined areas gave rise to thousands of small states and proto-states by 3000 BC. Some continued to share a common ritual center that linked the communities to a single symbolic order, but others developed along more independent lines. All was not peaceful, and the emergence of walled cities during this time is a clear indication that the political landscape was very much in flux.

The Hongshan culture of Inner Mongolia (located along the Laoha, Yingjin, and Daling rivers that empty into Bohai Bay) was scattered over a large area but had a single, common ritual center that consisted of at least 14 burial mounds and altars over several hill ridges. It dates from around 3500 BC but could have been founded ever earlier. Although there is no evidence of village settlements nearby, its size is much larger than one clan or village could support. In other words, though rituals would have been performed here for the elites, the large area implies that audiences for the ritual would have encompassed all the villages of the Hongshan. As a sacred landscape, the center might also have attracted supplicants from even further afield.

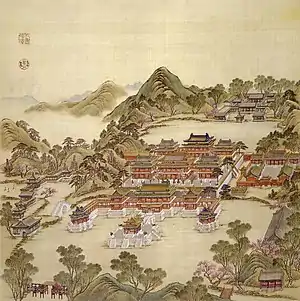

Features

The rectangular compound shown above has two sections of courtyards. The buildings on the axle line include central entrance, four-pointed pavilion, mountain-shaped front hall, artificial mountain and ponds, eight-pointed pavilion and mountain-shaped retiring quarters. The two sides of the central axle are arranged with corridor rooms symmetrically.

Architectural bilateral symmetry

.jpg.webp)

A very important feature in Chinese architecture is its emphasis on articulation and bilateral symmetry, which signifies balance. Bilateral symmetry and the articulation of buildings are found everywhere in Chinese architecture, from palace complexes to humble farmhouses. When possible, plans for renovation and extension of a house will often try to maintain this symmetry provided that there is enough capital to do so.[10] Secondary elements are positioned either side of main structures as two wings to maintain overall bilateral symmetry. The buildings are typically planned to contain an even number of columns in a structure to produce an odd number of bays (間). With the inclusion of a main door to a building in the center bay, symmetry is maintained.

In contrast to the buildings, the Chinese gardens tend to be asymmetrical. The principle underlying the garden's composition is to create enduring flow.[11] The design of the classic Chinese garden is based on the ideology of "Nature and Man in One", as opposed to the home itself, which is a symbol of the human sphere co-existing with, but separate from nature. So, the arrangement is as flexible as possible to let people feel they are surrounded by and in harmony with nature. The two essential elements of the garden are hill stones and water. The hill stones mean the pursuit of immortality and water represents emptiness and existence. The mountain belongs to yang (static beauty) and the water belongs to yin (dynamic wonder). They depend on each other and complete the whole nature.[12]

Enclosure

In much of traditional Chinese architecture, buildings or building complexes take up an entire property but enclose open spaces within themselves. These enclosed spaces come in two forms, the:[10]

- Courtyard (院): The use of open courtyards is a common feature in many types of Chinese architectures. This is best exemplified in the Siheyuan, which has consisted of an empty space surrounded by buildings connected with one another either directly or through verandas.

- "Sky well" (天井): Although large open courtyards are less commonly found in southern Chinese architecture, the concept of an "open space" surrounded by buildings, which is seen in northern courtyard complexes, can be seen in the southern building structure known as the "sky well". This structure is essentially a relatively enclosed courtyard formed from the intersections of closely spaced buildings and offer small opening to the sky through the roof space from the floor up.

These enclosures serve in temperature regulation and in venting the building complexes. Northern courtyards are typically open and facing the south to allow the maximum exposure of the building windows and walls to the sun while keeping the cold northern winds out. Southern sky wells are relatively small and serves to collect rain water from the roof tops. They perform the same duties as the Roman impluvium while restricting the amount of sunlight that enters the building. Sky wells also serve as vents for rising hot air, which draws cool air from the lower stories of the house and allows for exchange of cool air with the outside.

A skywell in a Fujian temple with enclosing halls and bays on four sides.

A skywell in a Fujian temple with enclosing halls and bays on four sides. A mid-20th-century colonial style Taiwanese building containing a skywell.

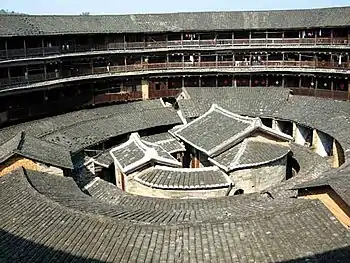

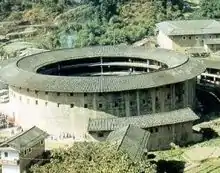

A mid-20th-century colonial style Taiwanese building containing a skywell. A tulou outer building encloses a smaller circular building, which encloses an ancestral hall and courtyard in the center.

A tulou outer building encloses a smaller circular building, which encloses an ancestral hall and courtyard in the center. A dugout dwelling enclosing an underground courtyard.

A dugout dwelling enclosing an underground courtyard. An enclosing courtyard on four sides from the Astor Court in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA.

An enclosing courtyard on four sides from the Astor Court in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA.

Hierarchy

The projected hierarchy and importance and uses of buildings in traditional Chinese architecture are based on the strict placement of buildings in a property/complex. Buildings with doors facing the front of the property are considered more important than those facing the sides. Buildings facing away from the front of the property are the least important.

South-facing buildings in the rear and more private location of the property with higher exposure to sunlight are held in higher esteem and reserved for elder members of the family or ancestral plaques. Buildings facing east and west are generally for junior members or branches of the family, while buildings near the front are typically for servants and hired help.[13]

Front-facing buildings in the back of properties are used particularly for rooms of celebratory rites and for the placement of ancestral halls and plaques. In multiple courtyard complexes, central courtyards and their buildings are considered more important than peripheral ones, the latter typically being used as storage or servants’ rooms or kitchens.[10]

Horizontal emphasis

Classical Chinese buildings, especially those of the wealthy, are built with an emphasis on breadth and less on height, featuring an enclosed heavy platform and a large roof that floats over this base, with the vertical walls not well emphasized. Buildings that were too high and large were considered unsightly, and therefore generally avoided.[14] Chinese architecture stresses the visual impact of the width of the buildings, using sheer scale to inspire awe in visitors.[15] This preference contrasts Western architecture, which tends to grow in height and depth. This often meant that pagodas towered above all other buildings in the skyline of a Chinese city.[16]

The halls and palaces in the Forbidden City, have rather low ceilings when compared to equivalent stately buildings in the West, but their external appearances suggest the all-embracing nature of imperial China. These ideas have found their way into modern Western architecture, for example through the work of Jørn Utzon.[17]

Cosmological concepts

Chinese architecture from early times used concepts from Chinese cosmology such as feng shui (geomancy) and Taoism to organize construction and layout from common residences to imperial and religious structures.[10] This includes the use of:

- Screen walls to face the main entrance of the house, which stems from the belief that evil things travel in straight lines.

- Talismans and imagery of good fortune:

- Door gods displayed on doorways to ward off evil and encourage the flow of good fortune

- Three anthropomorphic figures representing Fu Lu Shou (福祿壽 fú-lù-shòu) stars are prominently displayed, sometimes with the proclamation "the three stars are present" (三星宅 sān-xīng-zhài)

- Animals and fruits that symbolize good fortune and prosperity, such as bats and pomegranates, respectively. The association is often done through rebuses.

- Orienting the structure with its back to elevated landscape and ensuring that there is water in the front. Considerations are also made such that the generally windowless back of the structure faces the north, where the wind is coldest in the winter.

- Ponds, pools, wells, and other water sources are usually built into the structure.

- Aligning a building along a north/south axis, with the building facing south and the two sides facing east and west respectively.[16]

The use of certain colors, numbers and the cardinal directions in traditional Chinese architecture reflected the belief in a type of immanence, where the nature of a thing could be wholly contained in its own form. Beijing and Chang'an are examples of traditional Chinese town planning that represents these cosmological concepts.

Architectural types

There are various types of Chinese architecture. Some of these relate to the associated use of the structures, such as whether they were built for royals, commoners, or the religious.

Commoners

Due to primarily wooden construction and poor maintenance, far fewer examples of commoner's homes survive to this day compared to those of nobles. According to Matthew Korman, the average commoner's home did not change much, even centuries after the establishment of the universal style, such as early-20th-century homes, were very similar to late and mid imperial homes in layout and construction.[16]

These homes, be they those of bureaucrats, merchants or farmers, tended to follow a set pattern: the center of the building would be a shrine for the deities and the ancestors, which would also be used during festivities. On its two sides were bedrooms for the elders; the two wings of the building (known as "guardian dragons" by the Chinese) were for the junior members of the family, as well as the living room, the dining room, and the kitchen, although sometimes the living room could be very close to the center.[18]

Sometimes the extended families became so large that one or even two extra pairs of "wings" had to be built. This resulted in a U-shaped building, with a courtyard suitable for farm work.[16] Merchants and bureaucrats, however, preferred to close off the front with an imposing front gate. All buildings were legally regulated, and the law held that the number of stories, the length of the building and the colours used depended on the owner's class.

Some commoners living in areas plagued by bandits built communal fortresses called Tulou for protection. Often favoured by the Hakka in Fujian and Jiangxi, the design of Tulou also shows the Chinese ancient philosophy of harmony between people and environment. People used local materials to build the walls with rammed earth. There is no window to the outside on the lower two floors for defense, but it's open on the inside with a common courtyard and lets people get together easily.[19]

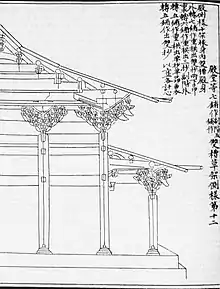

Imperial

There were certain architectural features that were reserved solely for buildings built for the Emperor of China. One example is the use of yellow roof tiles, yellow having been the Imperial color; yellow roof tiles still adorn most of the buildings within the Forbidden City. The Temple of Heaven, however, uses blue roof tiles to symbolize the sky. The roofs are almost invariably supported by brackets ("dougong"), a feature shared only with the largest of religious buildings. The wooden columns of the buildings, as well as the surfaces of the walls, tend to be red in color. Black is also a famous color often used in pagodas. It was believed that the gods are inspired by the black color to descend to the earth.

The Chinese 5-clawed dragon, adopted by the first Ming emperor for his personal use, was used as decoration on the beams, pillars, and on the doors on Imperial architecture. Curiously, the dragon was never used on roofs of imperial buildings.

Only the buildings used by the imperial family were allowed to have nine jian (間, space between two columns); only the gates used by the Emperor could have five arches, with the centre one, of course, being reserved for the Emperor himself. The ancient Chinese favored the color red. The buildings faced south because the north had a cold wind.

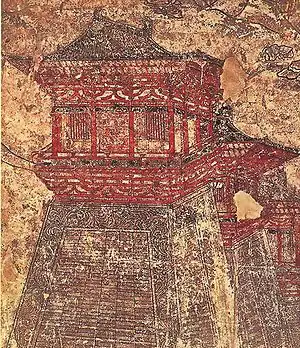

A tomb chamber of Luoyang, built during the Eastern Han Dynasty (AD 25–220) with incised wall decorations

A tomb chamber of Luoyang, built during the Eastern Han Dynasty (AD 25–220) with incised wall decorations The Great Red Gate at the Ming tombs near Beijing, built in the 15th century

The Great Red Gate at the Ming tombs near Beijing, built in the 15th century The yellow roof tiles and red wall in the Forbidden City (Palace Museum) grounds in Beijing, built during the Yongle era (1402–1424) of the Ming dynasty

The yellow roof tiles and red wall in the Forbidden City (Palace Museum) grounds in Beijing, built during the Yongle era (1402–1424) of the Ming dynasty

Beijing became the capital of China after the Mongol invasion of the 13th century, completing the easterly migration of the Chinese capital begun since the Jin dynasty. The Ming uprising in 1368 reasserted Chinese authority and fixed Beijing as the seat of imperial power for the next five centuries. The Emperor and the Empress lived in palaces on the central axis of the Forbidden City, the Crown Prince at the eastern side, and the concubines at the back (therefore the numerous imperial concubines were often referred to as "The Back Palace Three Thousand"). However, during the mid-Qing dynasty, the Emperor's residence was moved to the western side of the complex. It is misleading to speak of an axis in the Western sense of a visual perspective ordering facades, rather the Chinese axis is a line of privilege, usually built upon, regulating access—there are no vistas, but a series of gates and pavilions.

Numerology heavily influenced Imperial Architecture, hence the use of nine in much of construction (nine being the greatest single digit number) and the reason why the Forbidden City in Beijing is said to have 9,999.9 rooms—just short of the mythical 10,000 rooms in heaven. The importance of the East (the direction of the rising sun) in orienting and siting Imperial buildings is a form of solar worship found in many ancient cultures, where there is the notion of Ruler being affiliated with the Sun.

The tombs and mausoleums of imperial family members, such as the 8th-century Tang dynasty tombs at the Qianling Mausoleum, can also be counted as part of the imperial tradition in architecture. These above-ground earthen mounds and pyramids had subterranean shaft-and-vault structures that were lined with brick walls since at least the Warring States period (481–221 BC).[20]

Religious

Generally speaking, Buddhist architecture follows the imperial style. A large Buddhist monastery normally has a front hall, housing the statues of the Four Heavenly Kings, followed by a great hall, housing the statues of the Buddhas. Accommodations for the monks and the nuns are located at the two sides. Some of the greatest examples of this come from the 18th-century Puning Temple and Putuo Zongcheng Temple. Buddhist monasteries sometimes also have pagodas, which may house the relics of the Gautama Buddha; older pagodas tend to be four-sided, while later pagodas usually have eight sides.

Daoist architecture, on the other hand, usually follows the commoners' style. The main entrance is, however, usually at the side, out of superstition about demons which might try to enter the premise (see feng shui.) In contrast to the Buddhists, in a Daoist temple the main deity is located in the main hall at the front, the lesser deities in the back hall and at the sides. This is because Chinese people believe that even after the body has died, the soul is still alive. From the Han grave design, it shows the forces of cosmic yin and yang, the two forces from the heaven and earth that creates eternity.[21]

The tallest pre-modern building in China was built for both religious and martial purposes. The Liaodi Pagoda of 1055 AD stands at a height of 84 m (276 ft), and although it served as the crowning pagoda of the Kaiyuan monastery in old Dingzhou, Hebei, it was also used as a military watchtower for Song dynasty soldiers to observe potential Liao dynasty enemy movements.

The architecture of the mosques and gongbei tomb shrines of China's Muslims often combines traditional Chinese styles with Middle Eastern influences.

Gallery

A group of temples at the top of Mount Taishan, where structures have been built at the site since the 3rd century BC during the Han dynasty

A group of temples at the top of Mount Taishan, where structures have been built at the site since the 3rd century BC during the Han dynasty

Lianhuashan (lit. "lotus flower mountain") Temple in Dalian

Lianhuashan (lit. "lotus flower mountain") Temple in Dalian Songjiang Square Pagoda, built in the 11th century

Songjiang Square Pagoda, built in the 11th century The Nine Pinnacle Pagoda, built in the 8th century during the Tang dynasty

The Nine Pinnacle Pagoda, built in the 8th century during the Tang dynasty

The Fogong Temple Pagoda, located in Ying county, Shanxi province, built in 1056 during the Liao dynasty, is the oldest existent fully wooden pagoda in China

The Fogong Temple Pagoda, located in Ying county, Shanxi province, built in 1056 during the Liao dynasty, is the oldest existent fully wooden pagoda in China

The Songyue Pagoda, built in 523 AD during the Northern and Southern dynasties

The Songyue Pagoda, built in 523 AD during the Northern and Southern dynasties

A timber hall built in 857 during the Tang dynasty,[22] located at the Buddhist Foguang Temple in Mount Wutai, Shanxi

A timber hall built in 857 during the Tang dynasty,[22] located at the Buddhist Foguang Temple in Mount Wutai, Shanxi

Urban planning

Chinese urban planning is based on fengshui geomancy and the well-field system of land division, both used since the Neolithic age. The basic well-field diagram is overlaid with the luoshu, a magic square divided into 9 sub-squares, and linked with Chinese numerology.[23] In Southern Song dynasty (1131AD), the design of Hongcun city in Anhui was based around "harmony between man and nature", facing south and surrounded by mountains and water. According to the theory of the traditional Chinese fengshui geomancy, it is a carefully planned ancient village and show the Human-Nature Intergraded Ecological Planning concept.[24]

Since wars happened in northern China very often, people moved to southern China. The building method of a courtyard house was adapted to southern China. The village of Tungyuan in Fujian Province is a good example of a planned settlement that shows the Chinese feng shui elements – psychological self-defense and building structure – in the form of material self-defense.[25]

Construction

Materials and history

Wood was originally utilised as a primary building material because it was very common. Also, Chinese people trust that life is connecting with nature and humans should interact with animated things, therefore wood was favored as opposed to stone, which was associated with the homes of the dead.[26] However, unlike other building construction materials, old wooden structures often do not survive because they are more vulnerable to weathering and fires and are naturally subjected to rotting over time. Although now-nonexistent wooden residential towers, watchtowers, and pagodas predated it by centuries, the Songyue Pagoda built in 523 is the oldest extant pagoda in China; its use of brick instead of wood had much to do with its endurance throughout the centuries. From the Tang dynasty (618–907) onwards, brick and stone architecture gradually became more common and replaced wooden edifices. The earliest examples of this transition can be seen in building projects such as the Zhaozhou Bridge completed in 605 or the Xumi Pagoda built in 636, yet stone and brick architecture is known to have been used in subterranean tomb architecture of earlier dynasties.

In the early 20th century there were no known fully wood-constructed Tang Dynasty buildings that still existed; the oldest so far discovered was the 1931 find of Guanyin Pavilion at Dule Monastery, dated 984 during the Song.[3] This was until the architectural historians Liang Sicheng (1901–1972), Lin Huiyin (1904–1955), Mo Zongjiang (1916–1999), and (1902 – c. 1960s) discovered that the Great East Hall of Foguang Temple on Mount Wutai in Shanxi was reliably dated to the year 857 in June 1937.[3] The groundfloor dimensions for this monastic hall measures 34 by 17.66 m (111.5 by 57.9 ft).[30] A year after the discovery at Foguang, the main hall of nearby Nanchan Temple on Mount Wutai was reliably dated to the year 782,[31] while a total of six Tang era wooden buildings have been found by the 21st century.[32] The oldest existent fully wooden pagoda that has survived intact is the Pagoda of Fogong Temple of the Liao dynasty, located in Ying County of Shanxi. While the East Hall of Foguang Temple features only seven types of bracket arms in its construction, the 11th-century Pagoda of Fogong Temple features a total of fifty-four.[33]

The earliest walls and platforms in China were of rammed earth construction, and over time brick and stone became more frequently used. This can be seen in ancient sections of the Great Wall of China, while the brick and stone Great Wall seen today is a renovation of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

Structure

- Foundations: Most buildings are typically raised on raised platforms (臺基) as their foundations. Vertical structural beams may rest on raised stone pedestals (柱础) which occasionally rest on piles. In lower class construction, the platforms are constructed of rammed earth platforms that are unpaved or paved with brick or ceramics. In the simplest cases vertical structural beams are driven into the ground directly. Upper class constructions typically have high raised stone paved rammed earth or stone foundations with ornately carved heavy stone pedestals for supporting large vertical structural beams.[13] The vertical beams rest and remain on their pedestals solely by friction and the pressure exerted by the building structure.[34]

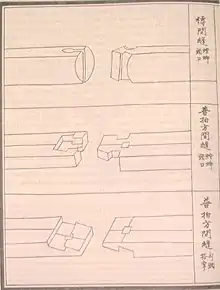

- Structural beams: Use of large structural timbers for primary support of the roof of a building. Wooden timber, usually large trimmed logs, are used as load-bearing columns and lateral beams for framing buildings and supporting the roofs. These beams are connected to each other directly or, in larger and higher class structures, tied indirectly together through the use of brackets. These structural timbers are prominently displayed in finished structures. It is not definitively known how the ancient builders raised the huge wooden load bearing columns into position.

- Structural connections: Timber frames are typically constructed with joinery and dowelling alone, seldom with the use of glue or nails. These types of semi-rigid structural joints allow the timber structure to resist bending and torsion while under high compression.[13] Structural stability is further ensured through the use of heavy beams and roofs, which weighs the structure down.[34] The lack of glue or nails in joinery, the use of non-rigid support such as dougong, and the used of wood as structural members allow the buildings to slide, flex, and hinge while absorbing shock, vibration, and groundshift from earthquakes without significant damage to its structure.[13] Dougong has a special function. The rich people applied valuable materials to decorate the Dougong for displaying their wealth. The common people used artwork to express their appreciation to the house.[35]

- Walls: The common use of curtain walls or door panels to delineate rooms or enclose a building, with the general de-emphasis of load-bearing walls in most higher class construction. However, with the reduction in availability of trees in the later dynasties for building structures, the use of load-bearing walls in non-governmental or religious construction increased, with brick and stone being commonly used.

- Roofs: Flat roofs are uncommon while gabled roofs are almost omnipresent in traditional Chinese architecture. Roofs are either built on roof cross-beams or rest directly on vertical structural beams. In higher class construction, roof supporting beams are supported through complex dougong bracketing systems that indirectly connect them to the primary structural beams.[13] Three main types of roofs are found:

- Straight inclined: Roofs with a single incline. These are the most economical type of roofing and are most prevalent in commoner architectures.

- Multi-inclined: Roofs with 2 or more sections of incline. These roofs are used in higher class constructions, from the dwellings of wealthy commoners to palaces.

- Sweeping: Roofs with a sweeping curvature that rises at the corners of the roof. This type of roof construction is usually reserved for temples and palaces although it may also be found in the homes of the wealthy. In the former cases, the ridges of the roof are usually highly decorated with ceramic figurines.

- Roof apex: The roof apex of a large hall is usually topped with a ridge of tiles and statues for both decorative purposes as well as to weigh down the layers of roofing tiles for stability. These ridges are often well decorated, especially for religious or palatial structures. In some regions of China, the ridges are sometimes extended or incorporated into the walls of the building to form matouqiang (horse-head walls), which serve as a fire deterrent from drifting embers.

- Roof top decorations: Symbolism can be found from colors of the eaves, roofing materials and roof top decorations. Gold/yellow is an auspicious (good) color, imperial roofs are gold or yellow. They are usually used by the emperor. Green roofs symbolize bamboo shafts, which, in turn, represent youth and longevity.[36]

Classification by structure

Chinese classifications for architecture include:

- 亭 (Chinese: 亭; pinyin: Tíng) ting (Chinese pavilions)

- 臺 (simplified Chinese: 台; traditional Chinese: 臺; pinyin: Taí) tai (terraces)

- 樓 (simplified Chinese: 楼; traditional Chinese: 樓; pinyin: Lóu) lou (multistory buildings)

- 閣 (simplified Chinese: 阁; traditional Chinese: 閣; pinyin: Gé) ge (two-story pavilions)

- 軒 (轩) xuan (verandas with windows)

- 塔 ta (Chinese pagodas)

- 榭 xie (pavilions or houses on terraces)

- 屋 wu (Rooms along roofed corridors)

- 斗拱 (Chinese: 斗拱; pinyin: Dǒugǒng) dougong interlocking wooden brackets, often used in clusters to support roofs and add ornamentation.

- 藻井 Caisson domed or coffered ceiling

- 宮 (simplified Chinese: 宫; traditional Chinese: 宮; pinyin: Gōng) palaces, larger buildings used as imperial residences, temples, or centers for cultural activities.

Miniature models

Although mostly only ruins of brick and rammed earth walls and towers from ancient China (i.e. before the 6th century AD) have survived, information on ancient Chinese architecture (especially wooden architecture) can be discerned from more or less realistic clay models of buildings created by the ancient Chinese as funerary items. This is similar to the paper joss houses burned in some modern Chinese funerals. The following models were made during the Han Dynasty (202 BC – AD 220):

A pottery palace from the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220)

A pottery palace from the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220) Two residential towers joined by a bridge, pottery miniature, Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220)

Two residential towers joined by a bridge, pottery miniature, Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220) A pottery tower from the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220)

A pottery tower from the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220) A ceramic model of a house with a courtyard, from the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220)

A ceramic model of a house with a courtyard, from the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220)

A pottery tower from the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220)

A pottery tower from the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220)

During the Jin dynasty (265–420) and the Six Dynasties, miniature models of buildings or entire architectural ensembles were often made to decorate the tops of the so-called "soul vases" (hunping), found in many tombs of that period.[37]

Gender in Chinese homes and society

Beyond the physically creative architecture techniques that the Chinese used, there was an "imaginary architecture"[38] that was implemented into a Chinese house. This imaginary architecture projected three major principles, that display a different set of messages about the relations between its inhabitants, the cosmos, and society at large, that each depicts a gender power imbalance.[38]

The first design principle was that the Chinese house was the embodiment of Neo-Confucian values. The values of the home incorporated prominently social values, collaborative values of loyalty, and values of respect and service. The values were depicted through how the Chinese home represented generations, gender, and age. Unlike western homes, the Chinese home was not a private space or a place separated from the state. It was a smaller community in itself. A place that sheltered a clan's or family's patrilineal kinship. It was quite common for houses to shelter "five generations under one roof."[38] In this patrilineal kinship, there are heavily influenced social concepts of Confucianist values from the Five Relationships between "ruler and subject, father and child, husband and wife, elder and younger brother and friends."[38]There is a large emphasis on the unequal relationship between the superior and subordinate. In the case of the relationship between husband and wife, it clearly was male-dominated. Despite this, the husband was still responsible for treating the partner with kindness, consideration, and understanding.

The second aspect was that the Chinese house was a cosmic space. The house was designed as a shelter to thwart away evil influences by channeling cosmic energies (qi) through means of incorporating Feng shui (also known as geomancy). Depending on the season, astral cycle, landscape's configuration of hills, rocks, trees, and water streams, and the house's arrangement, orientation, and details of roofs or gates, an arbitrary amount of energy would be produced. However, since the cosmic energy was such an arbitrary concept, it would be used in both moral and immoral ways. The moral way is by adding Feng shui to a local community temple. Yet, it other times Feng shui would be used competitively to raise the value of one's house at the expense of others. For example, if someone built a part of their house against the norm, their house would be considered a threat. Since it was throwing off the cosmic energy. In one detailed account, a fight broke out over Feng shui.[39]Additionally, this methodology was also incorporated inside the home. Symmetry, orientations, arrangements of objects, and cleanliness were important factors to cosmic energy. Even in poorer homes cleanliness and tidiness were highly desired since it would compensate for the cramped quarters. Sweeping was a daily task that was thought to be an act of purifying the room of pollutions such as dirt. As the Chinese historian, Sima Guang writes, "The servants of the inner and outer quarters and the concubines all rise at the first crow of the cock. After combing their hair, washing, and getting dressed, the male servants should sweep the halls and front courtyard; the doorman and older servants should sweep the middle courtyard, while the maids sweep the living quarters, arrange tables and chairs, and prepare for the toilet of the master and mistress." Through cleaning, the gender segregation of the Chinese household can be seen.[38]

The third component was that the house was a space of culture, by depicting the Chinese view of humanity. The house was a domestic domain that marked the separation of the undomesticated world. Commonly symbolized through walls and gates. Gates were first a physical barrier and second a kind of notice board for the outside world. Walls were the boundaries of a patriarchal domain. The home culture was also a place where family rules could be enforced, causing divides in the upbringing of the inhabitants. Most commonly, there was a wide gender distinction. Women were often hidden away within the inner walls to do wifely domestic duties. While men would be house representatives. In terms of the marriage duties, "Men would grow up, marry and likely die in the house win which he, his father and paternal grandfather had been born and in which his mother would live until her death. Women would leave their natal home on marriage to become a stranger in a new house."[38] Women wouldn't be accepted into a new home until they sired a child. Often new brides would be treated badly by the senior members of a household. In extreme cases, junior brides were treated like unpaid servants and forced to do unpleasant chores. Additionally, to women, marriage was thought of as a descent into hell. "The analogy of the wedding process with death is made explicit: the bride describes herself as being prepared for death, and the wedding process as the crossing of the yellow river that is the boundary between this life and the next. Shes appeals for justice, citing the valuable and unrecognized contribution she has made to her family. Her language is bitter and unrestrained, and she even curses the matchmaker and her future husband's family. Such lamenting can take place only within her parents' household and must cease halfway on the road to her new home, when the invisible boundary has been crossed."[38] As a result of this, men and women faced two vastly different lives.

The confinement of women was a method of controlling their sexuality. It was thought that women needed to be controlled so that they may not get pregnant by an outsider and then try to claim a state in the male's domain. In addition, wives were often represented as "gossiping troublemakers eager to stir up strife between otherwise devoted brothers, the root of family discord, requiring strict patriarchal control."[38]As a result, they were untrusted and were always considered to be involved in an illicit sexual relationship if they were in the company of another male.

Even though a couple would be married, husbands and wives did not stay in the same private room for long. During the day, men would go out or work in their studies so that they can avoid any unnecessary contact with female relatives. Women weren't allowed to leave the inner perimeter. If a woman had to leave the inner perimeter, they must cover their face with a veil or her sleeve. However, the inner quarters did provide women with some control over the patriarchal order. Since they had their own private room that men were not usually permitted to enter.

On all social levels and aspects of the Chinese home, the seclusion of women was ingrained into society. A married woman was a virtually a prisoner in her husband's domain while the husband "never had to leave his parents or his home, he knew which lineage and which landscape he belonged to from the time he began to understand the world."[38]

Influence from outside of China

Despite largely being self-developing, there have been periods where Chinese architecture received significant influence from abroad, particularly during conquest dynasties such as the Yuan and Qing, who tended to be more outward-looking.[40] The ruins of the Yuan capital of Khanbaliq under the Forbidden City in Beijing were analysed by scholars to be both distinct from previous styles and influential to many later architecture. Additionally the import of many Muslim officials, architects and scholars from the Islamic world during the Yuan led to an influx of Islamic design elements, especially in Chinese mosques.[41]

The Zhenghai Mosque in Ningbo city, Zhejiang province is a type of Islamic Architecture which appeared in China during the Song dynasty (990 AD). When the Arabic traders arrived at the big commercial city of Ningbo and settled down there, they spread the Muslim culture and built a mosque. Later, more mosques were built around Beijing.[42][43] The case itself is found in the mosques of Xi'an such as Xi'an Great Mosque and Daxuexi Alley Mosque.[44] Beijing's Mosques also follow essentially the norms of Chinese planning,[45] layout, design, and traditional wooden structure.[44][46][47]

There are many miniature pagodas in Northeast China. They were built by Buddhists during the Liao dynasty (907–1125), and the dynasty supported the practice of Buddhism. They developed some new types of Buddhist architecture building with bricks. Thus, one can find many such pagodas from Hebei Province to Beijing and Inner Mongolia.[48]

Influence on neighboring Asian countries

Chinese architecture has been influential in varying degrees in the development of the architecture of many neighboring East Asian countries. After the Tang dynasty, the era when much Chinese culture was imported en masse by neighboring nations, Chinese architecture has had a major influence on the architectural styles of Japan, Korea, Mongolia, and Vietnam where the East Asian hip-and-gable roof design is ubiquitous.[2][3][1]

Chinese architecture also has underlying influences in the architecture of various Southeast Asian countries. Certain Chinese architectural techniques were adopted by Thai artisans after trade commenced with the Yuan and Ming dynasty towards Thai architecture. Certain temple and palace roof tops were also built in Chinese-style and Chinese-style buildings can be found in Ayutthaya a nod towards the large numbers of Chinese shipbuilders, sailors and traders who came to the country.[5] In Indonesia, mosques bearing Chinese influence can be found in certain parts of the country. This influence is recent in comparison to other parts of Asia and is largely due to the sizable Chinese Indonesian community.[4]

In South Asia, Chinese architecture has played a significant role in shaping Sri Lankan architecture, alongside influences from India and other parts of Southeast Asia.[6][7] The Kandyan roof style, for example bears many similarities to the East Asian hip-and-gable roof technique which has its origins in China.[49]

The Chinese-origin guardian lion is also found in front of Buddhist temples, buildings and some Hindu temples (in Nepal) across Asia including Japan, Korea, Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Cambodia and Laos.[50]

Regional variation

There is considerable regional variance in traditional Chinese architecture, some of which are very divergent from general layouts. Several of the more notable regional styles include:

Shanxi architecture

Shanxi preserves the oldest wooden structures in China from Tang dynasty, including the Foguang Temple and Nanchan Temple. Yungang Grottoes in Datong and numerous Buddhist temples in the sacred Mount Wutai exemplify the religious architectures of China. Shanxi family compounds are representative of vernacular architecture in North China. In the mountainous areas of Shanxi, yaodong is a type of earth shelter that are commonly found.

Yungang Grottoes, Datong, China.

Yungang Grottoes, Datong, China. Temples in Mount Wutai

Temples in Mount Wutai The Grand East Hall of the Foguang Temple in Mount Wutai

The Grand East Hall of the Foguang Temple in Mount Wutai Birdview of the Zunsheng Temple in Mount Wutai

Birdview of the Zunsheng Temple in Mount Wutai Goddess Temple of Jinci, Taiyuan

Goddess Temple of Jinci, Taiyuan Pingyao City Wall

Pingyao City Wall A market street in Pingyao ancient city

A market street in Pingyao ancient city Wang Family Compound, in Lingshi

Wang Family Compound, in Lingshi Qiao Family Compound, Jingyi Court in Qi County

Qiao Family Compound, Jingyi Court in Qi County Chang Family Studies, Yuci

Chang Family Studies, Yuci Yaodong in Lingshi County, Shanxi

Yaodong in Lingshi County, Shanxi

Lingnan (Cantonese) architecture

The classical Lingnan architecture is used primarily in the southern province of Guangdong and the eastern half of the neighboring Guangxi. It is noted for its use of carvings and sculptures for decorations, green brick, balconies, "Cold alleys", "Narrow doors", and many other characteristics adaptive to the subtropical region.

The Ho Ancestral Hall in Panyu, Guangzhou; Built in 14th century, it utilizes manner door – a second door behind the main one, which is related to Cantonese Feng shui culture.

The Ho Ancestral Hall in Panyu, Guangzhou; Built in 14th century, it utilizes manner door – a second door behind the main one, which is related to Cantonese Feng shui culture. Chan Clan Academy in Gwongzau is often cited as a representative example of Lingnan architecture.

Chan Clan Academy in Gwongzau is often cited as a representative example of Lingnan architecture. A cold alley in Chan Clan Academy; A "Narrow Door" leads to the next alley.

A cold alley in Chan Clan Academy; A "Narrow Door" leads to the next alley. A monument in honor of the Cantonese folk hero Wong Fei-hung, in Foshan.

A monument in honor of the Cantonese folk hero Wong Fei-hung, in Foshan. Most Hongkongese are of Cantonese origin. Thus, Hong Kong naturally has a lot of buildings of classical Lingnan style. Pictured is a Mazu temple in Shek Pai Wan, Hong Kong.

Most Hongkongese are of Cantonese origin. Thus, Hong Kong naturally has a lot of buildings of classical Lingnan style. Pictured is a Mazu temple in Shek Pai Wan, Hong Kong.

Minnan (Hokkien) architecture

Minnan architecture, or Hokkien architecture, refers to the architectural style of the Hoklo people, the Han Chinese group who have been the dominant demographic of most of Fujian and Taiwan. This style is noted for its use of swallowtail roofs (heavily decorated upward-curving roof ridges) and "cut porcelain carving" for decorations.[51]

Cut porcelain carving decorations above the main door of Nanfeng Ancestral Temple.

Cut porcelain carving decorations above the main door of Nanfeng Ancestral Temple. A Mazu temple in Chiayi City, Taiwan.

A Mazu temple in Chiayi City, Taiwan.

Front entrance of Thian Hock Keng Temple, Singapore.

Front entrance of Thian Hock Keng Temple, Singapore.

Hakka architecture

Hakka people have been noted for building very distinctive walled villages in order to protect themselves from clan wars.

Gan architecture

The Gan Chinese-speaking province of Jiangxi is noted for its distinct style, making use of bricks, wood, and stones as materials, primarily erected with wooden frames.

Jiangxi's indigenous architecture – Liukeng village.

Jiangxi's indigenous architecture – Liukeng village. A "Pai tau uk" (牌頭屋) in Nanchang, Jiangxi.

A "Pai tau uk" (牌頭屋) in Nanchang, Jiangxi.

Yaodong architecture

The Jin Chinese cultural area of Shanxi and northern Shaanxi are noted for carving their homes into the sides of mountains. The soft rock of the Loess Plateau in this region makes for an excellent insulating material.

Tibetan architecture

See also

References

Citations

- L. Carrington Goodrich (2007). A Short History of the Chinese People. Sturgis Press. ISBN 978-1406769760.

- McCannon, John (19 March 2018). Barron's how to Prepare for the AP World History Examination. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 9780764118166. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. "The Tang Architectural Icon and the Politics of Chinese Architectural History," The Art Bulletin (Volume 86, Number 2, 2004): 228–254. Page 228.

- Formichi, Chiara (1 October 2013). Religious Pluralism, State and Society in Asia. Routledge. ISBN 9781134575428. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- Sthapitanond, Nithi; Mertens, Brian (19 March 2018). Architecture of Thailand: A Guide to Tradition and Contemporary Forms. Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 9789814260862. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- Winks, Robin (21 October 1999). The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume V: Historiography. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191542411. Retrieved 19 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- Bandaranayake, S. D. (19 March 1974). Sinhalese Monastic Architecture: The Viháras of Anurádhapura. BRILL. ISBN 9004039929. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- ddmdomag (9 April 2013). "Filipino-Chinese Coalitions". openthedorr. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Liang Sicheng, year 12, A pictorial history of Chinese architecture : a study of the development of its structural system and the evolution of its types, ed. by Wilma Fairbank, Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press.

- Knapp, Ronald G. (2006), Chinese Houses: The Architectural Heritage of a Nation, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8048-3537-4

- Handler, Sarah (19 January 2005), Ming Furniture in the Light of Chinese Architecture, Ten Speed Press

- Cui, Huaizu, and Qingqing Hu (2015), Creation and Appreciation of “Nature and Man in One” and Chinese Classic Beauty of Garden – Taking the Suzhou classic garden as an example, (https://www.shs-conferences.org/articles/shsconf/abs/2015/04/shsconf_icmetm2015_02001/shsconf_icmetm2015_02001.html Archived 2 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine). Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

- 浙江长城纪实文化传播公司 (2004), 中国古建筑, 齊魯音像出版社出版发行, ISBN 978-7-88408-237-7, OCLC 057661389

- Li, Yih-yuan (1979). "Chinese Geomancy and Ancestor Worship: A Further Discussion". Ancestors. DE GRUYTER MOUTON. pp. 329–338. doi:10.1515/9783110805314.329. ISBN 9783110805314.

- "Twelve. Typical Design Features of Ming Palaces and Altars in Beijing". Traditional Chinese Architecture. Princeton University Press. 31 January 2017. pp. 315–348. doi:10.1515/9781400885138-018. ISBN 9781400885138.

- Kohrman, Matthew (March 1998). "Technology and Gender: Fabrics of Power in Late Imperial China:Technology and Gender: Fabrics of Power in Late Imperial China". American Anthropologist. 100 (1): 236. doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.1.236.1. ISSN 0002-7294.

- Weston, Richard (2002). Utzon. Edition Blondal. p. 221. ISBN 978-87-88978-98-8.

- Cassault, Andre (1987). The Beijing Courtyard House. Open House International.

- Wang, Shao-Sen; Li, Su-Yu; and Shi-Jie Liao (2012). The Genes of Tulou: A Study on the Preservation and Sustainable Development of Tulou (http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/4/12/3377/htm Archived 4 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine). Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

- Guo, Qinghua. "Tomb Architecture of Dynastic China: Old and New Questions," Architectural History (Volume 47, 2004): 1–24. Page 12.

- Suhadolnik, Nataša Vampelj (2011). Han Mural Tombs: Reflection of Correlative Cosmology through Mural Paintings (https://revije.ff.uni-lj.si/as/article/view/2870 Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine). Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 4.0 License.

- Steinhardt (2004), 228–229.

- Schinz, 1996

- Zheng, Shanwen; Han, Baolong; Wang, Dang; and Zhiyun Ouyang (2018). Ecological Wisdom and Inspiration Underlying the Planning and Construction of Ancient Human Settlements: Case Study of Hongcun UNESCO World Heritage Site in China (http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/5/1345 Archived 17 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine). Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

- Jin, Xia; and Shang-chia Chiou (2015). Architectural Features and Preservation of Ancient Residential Complexes of the Changs in Xiangan, Xiamen, page 455 (https://www.int-arch-photogramm-remote-sens-spatial-inf-sci.net/XL-5-W7/453/2015/isprsarchives-XL-5-W7-453-2015.pdf Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine). Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

- Li, Lin; Tang, Lei; Zhu, Haihong; Zhang, Hang; Yang, Fan; and Wenmin Qin (2017). Semantic 3D Modeling Based on CityGML for Ancient Chinese-Style Architectural Roofs of Digital Heritage (http://www.mdpi.com/2220-9964/6/5/132/htm Archived 9 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine). Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

- Liu, Xujie (2002). "The Qin and Han Dynasties" in Chinese Architecture, 33–60. Edited by Nancy S. Steinhardt. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09559-7. Page 55.

- Steinhardt, Nancy N. (2005). "Pleasure tower model," in Recarving China's Past: Art, Archaeology, and Architecture of the 'Wu Family Shrines', 275–281. Edited by Naomi Noble Richard. New Haven and London: Yale University Press and Princeton University Art Museum. ISBN 0-300-10797-8. Pages 279–280.

- Wang Xudang, Li Zuixiong, and Zhang Lu (2010). "Condition, Conservation, and Reinforcement of the Yumen Pass and Hecang Earthen Ruins Near Dunhuang", in Neville Agnew (ed), Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China, June 28 – July 3, 2004, 351–357. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, J. Paul Getty Trust. ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1, pp 351–352.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. "The Tang Architectural Icon and the Politics of Chinese Architectural History," The Art Bulletin (Volume 86, Number 2, 2004): 228–254. Page 233.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. "The Tang Architectural Icon and the politics of Chinese Architectural History," The Art Bulletin (Volume 86, Number 2, 2004): 228–254. Page 228–229.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. "The Tang Architectural Icon and the Politics of Chinese Architectural History," The Art Bulletin (Volume 86, Number 2, 2004): 228–254. Page 238.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. "Liao: An Architectural Tradition in the Making," Artibus Asiae (Volume 54, Number 1/2, 1994): 5–39. Page 13.

- YU, Maohong; ODA, Yoshiya; FANG, Dongping; ZHAO, Junhai (2008), "Advances in structural mechanics of Chinese ancient architectures", Front. Archit. Civ. Eng. China, 2 (1): 1–25, doi:10.1007/s11709-008-0002-1, S2CID 108454838

- Jin, Xia; and Shang-chia Chiou (2015). Architectural Features and Preservation of Ancient Residential Complexes of the Changs in Xiangan, Xiamen, page 458 (https://www.int-arch-photogramm-remote-sens-spatial-inf-sci.net/XL-5-W7/453/2015/isprsarchives-XL-5-W7-453-2015.pdf Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine). Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dien, Albert E. (2007), Six dynasties civilization, Early Chinese civilization series, Yale University Press, pp. 214–215, ISBN 978-0-300-07404-8

- Bray, Francesca (1997). Technology and gender: fabrics of power in late imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press. hdl:2027/heb.02385.0001.001.

- Freedman, Maurice (1969). "Geomancy. Proceedings of the Royal Anthropological Institute". Proceedings of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Royal Anthropological Institute (1968): 5–15. doi:10.2307/3031743. JSTOR 3031703.

- James-Chakraborty, Kathleen (1 January 2014). "Ming and Qing China". Architecture since 1400. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 1–15. doi:10.5749/minnesota/9780816673964.003.0001. ISBN 9780816673964.

- Hou, Renzhi (2014). "Khanbaliq (1267–1368) of the Yüan Dynasty (1260–1368)". An Historical Geography of Peiping. China Academic Library. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 75–94. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55321-9_7. ISBN 9783642553202.

- Hagras, Hamada (2017). [103.17.76.13/index.php/JIA/article/view/3851/pdf "An Ancient Mosque in Ningbo, China "Historical and Architectural Study""] Check

|url=value (help). Journal of Islamic Architecture. 4 (3): 102–113. doi:10.18860/jia.v4i3.3851. - Hagras, Hamada Muhammed (2017). An Ancient Mosque In Ningbo, China “Historical And Architectural Study” (http://ejournal.uin-malang.ac.id/index.php/JIA/article/view/3851 Archived 2 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine). Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 4.0 License.

- Hagras, Hamada Muhammed (2019). "Xi'an Daxuexi Alley Mosque: Historical and Architectural Study". Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies. 9: 97–113. doi:10.21608/ejars.2019.38462.

- Hagras, Hamada Muhammed (22 May 2019). "Steles and Inscribed stones of the Beijing's mosques "archaeological study". Castle. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- Hagras, Hamada Muhammed (2016). "Chinese Traditional Courtyard Mosques: Beijing Madian Mosque". The Ages. 2.

- Hagras, Hamada Muhammed (2017). "Untraditional style of Chinese Courtyard Type Mosques: Beijing Tongzhou Mosque". The Ages. 2.

- Kim, Youn-mi (2017). Virtual Pilgrimage and Virtual Geography: Power of Liao Miniature Pagodas (907–1125) (http://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/8/10/206/htm Archived 17 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine). Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

- Paranavitana, Senarat; Prematilleka, Leelananda; Leeuw, Johanna Engelberta van Lohuizen-De (19 March 1978). Senarat Paranavitana Commemoration Volume. BRILL. ISBN 9004054553. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Monster Monday: Guardian Lions". kgorman.ca. 22 January 2013. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Hongyin, X. (2009). Research on the comparison of the Minnan new jiageng architecture [J]. Fujian Architecture & Construction, 5, 008.

Sources

- Liang, Ssu-ch'eng 1984, A pictorial history of Chinese architecture: a study of the development of its structural system and the evolution of its types, ed. by Wilma Fairbanks, Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press

- Schinz, Alfred (1996), The magic square: cities in ancient China, Edition Axel Menges, p. 428, ISBN 978-3-930698-02-8

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. "Liao: An Architectural Tradition in the Making," Artibus Asiae (Volume 54, Number 1/2, 1994): 5–39.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. "The Tang Architectural Icon and the Politics of Chinese Architectural History," The Art Bulletin (Volume 86, Number 2, 2004): 228–254.

- Weston, Richard. 2002. Utzon : inspiration, vision, architecture. Hellerup: Blondal.

Further reading

- Fletcher, Banister; Cruickshank, Dan, Sir Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture, Architectural Press, 20th edition, 1996 (first published 1896). ISBN 0-7506-2267-9. Cf. Part Four, Chapter 24.

- Sickman L and Soper A. The Art and Architecture of China (Penguin Books, 1956).

- KNAPP, RONALD G. (2000). CHINA'S OLD DWELLINGS. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2075-6. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Genovese Paolo Vincenzo Harmony in Space. Introduction to Chinese Architecture (Libria, 2017) ISBN 88-6764-121-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of China. |

- Yin Yu Tang: A Chinese Home To explore an in depth look into the ancient architecture of the Huang family's domestic life in China, the Yin Yu Tang house offers an interactive view of the typical domestic architecture of the Qing dynasty.

- Herbert Offen Research Collection An excellent bibliography of publicly accessible books and manuscripts on Chinese architecture.

- Islamic Architecture in China Introduction to the Chinese Mosques in South, West, and North respectively

- Chinese Vernacular Architecture & General Chinese Architecture—Web Links Chinese Vernacular Architecture & General Chinese Architecture—Web Links

- Chinese Residential Houses Ten types of Chinese residential houses

- Asian Historical Architecture

- Web Resources of Chinese Architecture History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)