Battle of Sidi Bou Zid

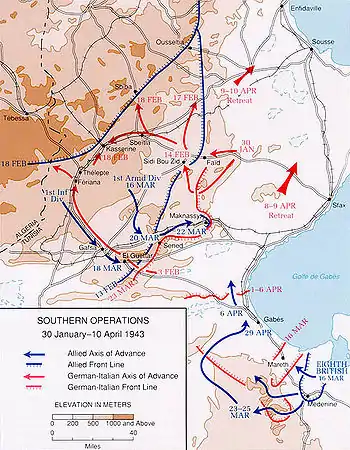

The Battle of Sidi Bou Zid (Unternehmen Frühlingswind/Operation Spring Breeze) took place during the Tunisia Campaign from 14–17 February 1943, in World War II. The battle was fought around Sidi Bou Zid, where a large number of US Army units were mauled by German and Italian forces. It resulted in the Axis forces recapturing the strategically important town of Sbeitla in central Tunisia.

| Battle of Sidi Bou Zid | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Tunisia Campaign of World War II | |||||||

Tunisian Campaign, January–April 1943 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2,546 missing 103 tanks[1] | |||||||

Sidi Bou Zid Sidi Bou Zid in Tunisia | |||||||

The battle was planned by the Germans to be a two-part offensive-defensive operation against US positions in western Tunisia. Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen von Arnim commanded several experienced combat units, including the 10th Panzer Division and the 21st Panzer Division of the 5th Panzer Army, which were to sweep north and west towards the Kasserine Pass, while another battle group attacked Sidi Bou Zid from the south. Facing the attack was the II US Corps under Major General Lloyd Fredendall.

In a few days, the Axis attack forced the II US Corps to take up new defensive positions outside Sbiba. Axis troops were then given time to consolidate their new front line west of Sbeitla. The success of the offensive led the German High Command to conclude that despite being well equipped, American forces were no match for experienced Axis combat troops.

Background

The Allied attempt to capture Tunis, in late 1942 after Operation Torch, had failed, and since the year end a lull had settled on the theatre, as both sides paused to rebuild their strength. Hans-Jürgen von Arnim had been given command of the Axis forces defending Tunisia and reinforcements led to the force being named the 5th Panzer Army (5.Panzer-Armee). Arnim chose to maintain the initiative gained when the Allies had been driven back the previous year by making spoiling attacks to keep his intentions hidden.

In January 1943, the German-Italian Panzer Army (Deutsch-Italienische Panzerarmee) commanded by General Erwin Rommel, had retreated to the Mareth Line, a line of defensive fortifications near the coastal town of Medenine in southern Tunisia, built by the French before the war. The Axis forces joined and in the Sidi Bou Zid area there were elements from both armies, among them the 21st Panzer Division of the Afrika Korps, transferred from German-Italian Panzer Army, and the 10th Panzer Division from the 5th Panzer Army.

Most of Tunisia was under Axis occupation but in November 1942, the Eastern Dorsale of the Atlas Mountains had been captured by the Allies.[2] The Eastern Dorsale was held by elements of the inexperienced II US Corps (Lieutenant-General Lloyd Fredendall) and the poorly equipped French XIX Corps (Alphonse Juin). Fredendall made Tebessa, over 80 mi (130 km) back, his headquarters and rarely visited the front.[3] In the absence of intelligence as to Axis intentions, Fredendall dispersed his forces to cover all eventualities, which left his units too far apart for mutual support. At Sidi Bou Zid, he had overruled his divisional commanders and ordered the defensive dispositions without studying the ground. Sidi Bou Zid was defended by the 34th US Infantry Division 168th Regimental Combat Team (RCT) (Colonel Thomas Drake) and the tanks of the 1st US Armored Division Combat Command A (CC A). Fredendall had caused most of this force to be placed in defensive "islands" on high ground, which risked defeat in detail.[4]

Rommel was conscious of the danger of an attack by the Allies on the Eastern Dorsale towards the coast, about 60 mi (97 km) to the east, which could divide the Axis forces and isolate the German-Italian Panzer Army from its line of supply from Tunis. On 30 January, Arnim had sent the 21st Panzer Division to attack the Faid Pass, held by the French XIX Corps. Fredendall had reacted slowly, and Arnim's troops had overcome fierce French resistance and achieved their objectives while inflicting heavy casualties.

Prelude

German plan

Two offensive-defensive operations were planned, with Unternehmen Frühlingswind to be conducted by the 10th and 21st Panzer divisions against US positions at Sidi Bou Zid, west of Faïd, after which the 21st Panzer Division would join a battlegroup of the 1st Italian Army to attack Gafsa in Unternehmen Morgenluft and the 10th Panzer Division moved north for an attack west of Kairouan. Unternehmen Frühlingswind was to begin from 12–14 February.[5]

Battle

At 04:00 on 14 February four battle groups totalling 140 German tanks drawn from 10th and 21st Panzer divisions (Lieutenant General Heinz Ziegler), advanced through Faïd and Maizila passes, sites that General Dwight D. Eisenhower had inspected three hours earlier, to attack Sidi Bou Zid.[4] The attack started with tanks of the 10th Panzer Division under the cover of a sandstorm advancing westward from Faïd in two battle groups (the Reimann and Gerhardt groups). Elements of CC A tried to delay the German advance by firing a 105 mm M101 howitzer mounted on an M4 Sherman tank. The Germans responded by shelling the American battle positions with 88mm guns. By 10 a.m. the Germans had circled Djebel Lessouda (defended by Lessouda Force, an armoured battalion group commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John K. Waters, George S. Patton's son-in-law) and joined up north of Sidi Bou Zid.[6]

Kampfgruppe Schütte and Kampfgruppe Stenckhoff of the 21st Panzer Division had secured the Maizila Pass to the south and Kampfgruppe Schütte headed north to engage two battalions of the 168th RCT[7] on Djebel Ksaira while Kampfgruppe Stenckhoff headed north-west to Bir el Hafey in order to swing round and make the approach to Sidi Bou Zid from the west during the afternoon. Under heavy shelling from the Kampfgruppe Schütte, Colonel Thomas Drake requested permission to retreat, which was denied by Fredendall, who ordered him to hold his positions and wait for reinforcements, which never arrived. By 5 p.m. Kampfgruppe Stenckhoff and the 10th Panzer Division had attacked CC A which had been driven nearly 15 miles (24 km) west to Djebel Hamra, with the loss of 44 tanks and many guns. The infantry were marooned on the high ground at Djebel Lessouda, Djebel Ksaira and Djebel Garet Hadid.[8]

During the night the 1st US Armored Division commander Orlando Ward moved up Combat Command C (CC C) to Djebel Hamra, to counter-attack Sidi Bou Zid on 15 February but the attack was over flat exposed country and was bombed and strafed early in the move, then found itself between the two Panzer divisions, with more than 80 Panzer IV, Panzer III and Tiger I tanks.[9] CC C retreated, losing 46 medium tanks, 130 vehicles and 9 self-propelled guns, narrowly regaining the position at Djebel Hamra. By the evening, Arnim had ordered three of the battle groups to head towards Sbeitla and were engaged by the remnants of CC A and CC C which were forced back. On 16 February, helped by intensive air support, they drove back the fresh Combat Command B (CC B) and entered Sbeitla.[10]

Aftermath

The experienced Germans performed well and caused many US losses before General Anderson, who had been appointed to co-ordinate Allied operations in Tunisia, ordered an Allied withdrawal on 17 February. The left (northern) flank of the First Army retreated from a line from Fondouk to Faïd and Gafsa to better defensive positions in front of Sbiba and Tebessa. Eisenhower blamed himself for trying to do too much and the sudden French collapse in the central mountains. Confusing and overlapping command arrangements made things worse. When the II US Corps was forced out of Sbeitla on 17 February and Axis forces converged on Kasserine, the Axis lack of unity of command and unclear objectives had a similar effect on Axis operations.[11]

The poor performance of the Allies during the actions of late January and the first half of February, as well as at the later Battle of the Kasserine Pass led the Axis commanders to conclude that, while US units were well equipped, they were inferior in leadership and tactics. This became received wisdom among the Axis forces and resulted in a later underestimation of Allied capabilities as they gained experience and replaced poor commanders.

Footnotes

- Anderson 1993, p. 16.

- Billings 1990.

- Porch 2005, p. 383.

- Watson 2007, p. 75.

- Hinsley 1994, pp. 276–277.

- Playfair et al. 2004, pp. 290–291.

- Watson 2007, p. 76.

- Playfair et al. 2004, p. 291.

- Watson 2007, p. 77.

- Playfair et al. 2004, pp. 291–294.

- Howard 1972, pp. 344–345.

References

- Anderson, Charles R. (1993). Tunisia 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. WWII Campaigns. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 0-16-038106-1. CMH Pub 72-12.

- Billings, Linwood W. (1990). "The Tunisian Task Force". Historicaltextarchive.com. Archived from the original on 2007-03-09. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- Hinsley, F. H. (1994) [1993]. British Intelligence in the Second World War. Its influence on Strategy and Operations. History of the Second World War. abridged edition (2nd rev. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630961-7.

- Howard, M. (1972). Grand Strategy: August 1942 – September 1943. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. IV. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630075-1.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; Molony, Brigadier C. J. C.; Flynn, Captain F. C. (RN) & Gleave, Group Captain T. P. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1966]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Destruction of the Axis Forces in Africa. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. IV. Uckfield: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-068-9.

- Porch, Douglas (2005) [2004]. Hitler's Mediterranean Gamble (Cassell Military Paperbacks ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-304-36705-4.

- Watson, Bruce Allen (2007) [1999]. Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942–43. Stackpole Military History. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6.

Further reading

- Bedell, A. D.; Arregui, A.; Boccolucci, D. J.; Cassetori, M. H.; Chandler, R. V. (1984). "Battle Analysis of the Battle of Sidi Bou Zid, Tunisia, North Africa. Defensive, Encircled Forces, 14 February 1943" (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, KS: Army Command and General Staff College Combat Studies Institute. OCLC 831708957. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- Howe, G. F. (1991) [1957]. Northwest Africa: Seizing the Initiative in the West. United States Army in World War II: Mediterranean Theatre of Operations (repr. ed.). Washington: Department of the Army. ISBN 978-0-16-001911-1. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Sidi Bou Zid. |