Battle of Alam el Halfa

The Battle of Alam el Halfa took place between 30 August and 5 September 1942 south of El Alamein during the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War. Panzerarmee Afrika (Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel), attempted an envelopment of the British Eighth Army (Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery). In Unternehmen Brandung (Operation Surf), the last big Axis offensive of the Western Desert Campaign, Rommel intended to defeat the Eighth Army before Allied reinforcements arrived.

| Battle of Alam el Halfa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War | |||||||

.png.webp) Map of the battlefield (in German) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

XIII Corps (Eighth Army): 4 divisions |

Panzer Army Africa: 6 divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1,750 killed, wounded or captured[1] 68 tanks[1] 67 aircraft[2] |

2,900 killed, wounded or captured[1] 49 tanks[1] 36 aircraft 60 guns[1] 400 transport vehicles[1] | ||||||

Montgomery knew of Axis intentions through Ultra signals intercepts and left a gap in the southern sector of the front, knowing that Rommel planned to attack there and deployed the bulk of his armour and artillery around Alam el Halfa Ridge, 20 miles (32 km) behind the front. Unlike in previous engagements, Montgomery ordered that the tanks were to be used as anti-tank guns, remaining in their defensive positions on the ridge. When Axis attacks on the ridge failed and short on supplies, Rommel ordered a withdrawal. The 2nd New Zealand Division conducted Operation Beresford against Italian positions, which was a costly failure.

Montgomery chose not to exploit his defensive victory, preferring to continue the methodical build up of strength for his autumn offensive, the Second Battle of El Alamein. Rommel claimed that British air superiority determined the result, being unaware of British Ultra intelligence. Rommel adapted to the increasing Allied dominance in the air by keeping his forces dispersed. With the failure at Alam Halfa, the Axis forces in Africa lost the initiative and Axis strategic aims in Africa were no longer possible.

Background

A lull followed the Axis failure in the First Battle of El Alamein and the counterattacks by the Eighth Army (General Sir Claude Auchinleck) in July 1942. At Alamein, the Axis supply position was precarious because the main supply ports of Benghazi and Tobruk were 800 mi (1,300 km) and 400 mi (640 km) from the front and Tripoli—1,200 mi (1,900 km) away—was almost redundant because of its distance from the front.[3] The original Axis plan for the Battle of Gazala in June had been to capture Tobruk then pause for six weeks on the Egyptian frontier to prepare an invasion of Egypt. The magnitude of the Axis victory at Gazala led Rommel to pursue the Eighth Army to deny the Allies time to organise another defensive front west of Cairo and the Suez Canal. Axis air forces which had been allocated to Operation Herkules, an attack on Malta, were diverted into Egypt.[4]

The British in Malta were able to rebuild their strength to resume attacks on Axis supply convoys to North Africa. From mid-August there was a big increase in Axis losses at sea, notably from a reinforced Mediterranean submarine force.[4] At the end of August, the Axis forces had been reinforced by troops flown from Crete but were short of supplies, notably ammunition and petrol.[5][6] There was a recovery in the armoured strength of Panzerarmee Afrika in August, German tank strength rising from 133 "runners" to 234 and the number of Italian runners increased from 96 to 281 (of which 234 were medium tanks).[7] Luftwaffe strength increased to 298 aircraft from 210 before the Battle of Gazala and the Italian number rising to 460 aircraft.[7]

General Sir Harold Alexander—the new Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of Middle East Command—had only a short distance from the supply bases and ports in Egypt to the front line but supplies from Britain, the Commonwealth and the United States still took a long time to arrive. By the summer of 1942, equipment receipts began to increase, notably of new Sherman tanks and six-pounder anti-tank guns to supplement obsolete two-pounders. The RAF and associated air forces under command, supported by new American squadrons maintained a considerable degree of air superiority.[6] Sources of military intelligence were integrated and by mid August, British and Allied forces were benefiting from tactically useful information.[8]

German intelligence had warned Rommel of the arrival of a 100,000 long tons (100,000 t) Allied convoy bringing new vehicles for the Allies in Egypt; reinforcements for the British would tilt the balance of advantage against the Axis.[9][10] Rommel demanded from the Italian Comando Supremo in Rome 6,000 short tons (5,400 t) of fuel and 2,500 short tons (2,300 t) of ammunition before attacking at the end of the month but by 29 August, over 50 percent of the supply ships from Italy had been sunk and only 1,500 short tons (1,400 t) of fuel had arrived at Tobruk. Rommel had to gamble on a quick victory before the increasing power of the Eighth Army made defeat inevitable. After Albert Kesselring had agreed to lend some Luftwaffe fuel, Rommel had enough for 150 mi (240 km) per vehicle with the troops and 250 mi (400 km) for other vehicles.[11]

Prelude

Plan

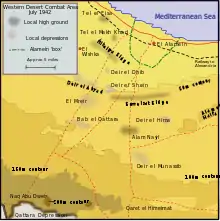

At El Alamein an attack by the Axis would have to pass between the coast and the Qattara Depression about 40 mi (64 km) to the south and impassable for tanks. The Eighth Army defences were quite strong but Rommel believed that the south end between Munassib and Qaret El Himeimat, was lightly held and not extensively mined.[12] One account indicated the northern and central sectors of the front were so strongly fortified that the southern stretch of 15 mi (24 km) between the New Zealand "box" on the Alam Nayil Ridge and the Qattara Depression, was the only place where an attack could quickly succeed. Since surprise in location was impossible, Rommel had to depend on achieving surprise by time and speed. By rapidly breaking through in the south, Axis forces might get astride the Eighth Army supply routes, throw it off balance and disorganise its defence.[13]

Rommel planned a night attack to be well beyond the Eighth Army minefields before sunrise. In the north, the XXI Infantry Corps (XXI Corpo d'Armata, Generale Enea Navarini) comprising the "Trento" and "Bologna" Divisions, the XXXI Guastatori (Sappers) Battalion, the German 164th Light Division and elements of the Ramcke Parachute Brigade, was to conduct a frontal demonstration to fix the defenders. The main attack was to be led by the 15th Panzer Division and the 21st Panzer Division and the 90th Light Division to the south which would turn north once through the British minefields.[13] The Eighth Army would be surrounded and destroyed, leaving the Axis forces with a promenade through Egypt to the Suez Canal.[14][15]

Allied defences

British Ultra decrypts had anticipated an Axis attack[16][17] and Auchinleck set out the basic defensive plan with several contingencies for defensive works around Alexandria and Cairo in case Axis armour broke through. On 13 August, command of the Eighth Army passed to Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery. After visiting the front, Montgomery ordered that the contingency plans be destroyed and emphasised his intention to hold the ground around Alamein at all costs.[18] In the northern sector, just south of Ruweisat Ridge to the coast, XXX Corps (Lieutenant-General William Ramsden) comprising the 9th Australian Division, the 1st South African Infantry Division and the 5th Indian Infantry Division with the 23rd Armoured Brigade in reserve was deployed behind minefields.[19][20]

XIII Corps (Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks) held the ground south of Ruweisat Ridge. The 2nd New Zealand Division was deployed on a 5 mi (8.0 km) front south of the ridge in the New Zealand Box, which formed a corner to the main defences with its hinge of the higher ground at Alam Nayil. Since the featureless southern sector was hard to defend against an armoured attack, Montgomery chose to hold lightly the 12 mi (19 km) front from the New Zealand Box to Qaret el Himeimat on the edge of the Qattara Depression, to encourage Rommel to take the bait and attack there. This gap would be mined and wired; the 7th Motor Brigade Group and 4th Light Armoured Brigade (7th Armoured Division) would cover the minefields but withdraw when necessary.[21]

The attackers would meet the main defensive positions when they swung north and approached the Alam el Halfa ridge, behind the Eighth Army front. The bulk of the British medium tanks (in 22nd Armoured Brigade) and anti-tank units were dug in to wait for the Axis attack. Behind the British armour, on the high ground to the north east would be two infantry brigades of the 44th (Home Counties) Division and concentrations of divisional and corps artillery.[22] The 10th Armoured Division had been refitting in the Nile Delta with General Grant tanks with the effective 75 millimetres (2.95 in) main gun and would reinforce the Alam El Halfa position when available. Most of the 8th Armoured Brigade had arrived by 30 August and took post to manoeuvre on the left of 22nd Armoured Brigade and on the flank of the enemy's expected advance.[23][19] Once Montgomery had seen the Axis dispositions after the initial advance, he released the 23rd Armoured Brigade, in XXX Corps reserve at the eastern end of Ruweisat Ridge, to XIII Corps, attached to the 10th Armoured Division. By 13:00 on 31 August, 100 Valentine tanks had moved to fill the gap between 22nd Armoured Brigade and the New Zealanders.[24]

Battle

30/31 August

The attack started on the night of 30 August, taking advantage of a full moon. From the start, things went wrong for Rommel; the RAF spotted the Axis vehicle concentrations and unleashed several air attacks on them. Fairey Albacores of the Royal Navy dropped flares to illuminate targets for Vickers Wellington medium bombers and for the artillery;[25] also, the minefields that were thought to be thin turned out to be deep. The British units covering the minefields were the two brigades of the 7th Armoured Division (7th Motor and 4th Armoured), whose orders were to inflict maximum casualties before retiring. This they did, and the Axis losses began to rise. They included General Walther Nehring, the Afrika Korps commander, wounded in an air raid, and General Georg von Bismarck, commander of the 21st Panzer Division, killed by a mine explosion.[26]

31 August

Despite these difficulties, Rommel's forces were through the minefields by midday the next day and had wheeled left and were drawn up ready to make the main attack originally scheduled for 06:00.[27] The late running of the planned schedule and the continued harassing flank attacks from the 7th Armoured Division had forced them to turn north into Montgomery's flank further west than originally planned and directly toward the prepared defences on Alam el Halfa. At 13:00, the 15th Panzer Division set off, followed an hour later by 21st Panzer. The Allied units holding the ridge were the British 22nd Armoured Brigade with 92 Grants and 74 light tanks, supported by anti-tank units with six-pounder guns and the artillery of the 44th (Home Counties) Division and the 2nd New Zealand Division.[28]

The Axis forces had approximately 200 gun-armed tanks in the two Panzer divisions and 240 in the two Italian armoured divisions. The Italian tanks were mostly obsolete models, with the exception of the Semovente da 75/18, which could defeat Allied medium tanks using HEAT ammunition, which could penetrate 70 mm of armour at 50 meters.[29] The Germans had 74 up-armoured Panzer IIIs with long-barrelled 50 mm (1.97 in) guns (Pz.Kpfw III Ausf.L) and 27 Panzer IVs with long 75 mm guns (Pz.Kpfw IV Ausf.F2).[30] The British had 700 tanks at the front, of which 160 were Grants. Only 500 of the British tanks were engaged in the armoured battle, which was brief.[31]

As the Panzer divisions approached the ridge, the Panzer IV F2 tanks opened fire at long range and destroyed several British tanks. The British Grants were handicapped by their hull-mounted guns that prevented them from firing from hull-down positions. When the Germans came into range, they were exposed to the fire of the brigade and their tanks were hard hit. An attempt to outflank the British was thwarted by anti-tank guns and with night beginning to fall and fuel running short because of the delays and heavy consumption over the bad 'going', General Gustav von Vaerst, the Afrika Korps commander, ordered the Panzers to pull back. During this engagement, the Germans lost 22 tanks and the British 21.[32]

There had also been hard infantry fighting. In the central sector, the Italians of the 25th Infantry Division "Bologna" and German Infantry Regiment 433 attacked several Indian, South African and New Zealand units on Ruweisat Ridge, and managed to capture Point 211 but were later driven off by a counter-attack.[33] Although the Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45 refers to the Italo-German infantry action as simply 'feints',[34] Captain Cyril Falls, a British military historian, wrote that it was a strong counter-attack requiring an equal response.[lower-alpha 1]

1–2 September

The night of 31 August – 1 September brought no respite for the Axis forces, as the Albacore and Wellington bombers returned to the attack, concentrating on the Axis supply lines. This added to Rommel's supply difficulties as Allied action had sunk over 50 percent of the 5,000 long tons (5,100 t) of petrol promised to him by Mussolini.[36] On 1 September the 21st Panzer Division was inactive (probably because of a lack of fuel) and operations were limited to an attack by the 15th Panzer Division toward the eastern flank of the 22nd Armoured Brigade.[24] The attack started at dawn but was quickly stopped by a flank attack from the 8th Armoured Brigade. The Germans suffered little, as the British were under orders to spare their tanks for the coming offensive but they could make no headway either and were heavily shelled.[37] The 133rd Armoured Division Littorio and 132nd Armoured Division Ariete had moved up on the left of the Afrika Korps and the 90th Light Division and elements of Italian X Corps had drawn up to face the southern flank of the New Zealand box.[24] Air raids continued throughout the day and night and on the morning of 2 September, realising his offensive had failed and that staying in the salient would only add to his losses, Rommel decided to withdraw.[38]

Axis withdrawal

In a message to Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), Rommel justified his decision to abandon the offensive by the lack of fuel, Allied air superiority and the loss of surprise.[39] On 2 September, Armoured cars of the 4/8th Hussars (4th Armoured Brigade) attacked 300 Axis supply lorries near Himeimat, destroying 57 and Italian armoured units had to be moved to protect Axis supply lines. In the air the Desert Air Force (DAF) flew 167 bomber and 501 fighter sorties.[38] Montgomery realised the Afrika Korps was about to withdraw and planned attacks by the 7th Armoured Division and the 2nd New Zealand Division (Lieutenant-General Bernard Freyberg) under the proviso that they were to avoid excessive losses. The 7th Armoured Division managed harassment raids but the New Zealand Division attacked with the experienced 5th New Zealand Brigade, the new 132nd Infantry Brigade (Brigadier C. B. Robertson) of the 44th (Home Counties) Division under command and tank support from the 46th Royal Tank regiment (46th RTR, 23rd Army Tank Brigade).[40]

3–4 September, Operation Beresford

Operation Beresford began at 22:30 on 3. September. The 5th New Zealand Brigade on the left inflicted many casualties on the Italian defenders and defeated Axis counter-attacks the next morning.[40] The Axis defenders were alerted by diversionary raids by the 6th New Zealand Brigade (Brigadier George Clifton) on the right flank of the 132nd Infantry Brigade which was an hour late arriving on their start line. The attack was a costly failure; the Valentine tanks of the 46th RTR got lost in the dark and ran onto a minefield where twelve were knocked out. The 90th Light Division inflicted 697 casualties on the 132nd Infantry Brigade and 275 casualties on the New Zealanders.[41] Robertson was wounded and Clifton was captured by a patrol of the X Battalion of the Italian "Folgore" Division.[42] The vigorous Axis defence suggested to Freyberg that another attack was unlikely to succeed and advised that the troops should be withdrawn from their very exposed positions and the operation called off. Montgomery and Horrocks agreed and the troops were withdrawn on the night of 4 September.[42] Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein wrote later,

An attack by our Luftwaffe against the 10th Indian Div [sic], which was in the assembly area for a counter attack against the centre of the front, caused the units which were assembled there to scatter to the winds. Also, all other attacks launched by other units against our flanks, especially the New Zealanders, were too weak to be able to effect a penetration—they could be repulsed. A night attack conducted against the X Italian Corps resulted in especially high losses for the British. Countless enemy dead lay on the battlefield and 200 prisoners were taken among whom was Gen (sic) Clifton, commanding general of the 6th New Zealand Brigade.

— Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein[23]

5 September

The position north of the New Zealand Division was held by 5th Indian Infantry Division, relieved by the 4th Indian Infantry Division on 9 September. After this failure against the Folgore Division, the Afrika Korps retired unhindered, except for attacks by the DAF, which flew 957 sorties in 24 hours.[43] By 5 September, the Axis units were back almost on their starting positions and the battle was over.

Aftermath

During the Battle of Alam el Halfa, the Allies suffered 1,750 casualties, compared to 2,930 for the Axis. The Allies lost more tanks than the Axis but for the first time in this campaign there was no great disproportion in tank losses. Constant harassment by the RAF cost the Panzerarmee Afrika many transport vehicles.[1] The battle was the last big offensive undertaken by the Axis in North Africa and the superior firepower of the Allies and their mastery of the skies brought them victory.[1] There has been criticism of Montgomery's leadership during the battle, especially his choice to avoid losses, which prevented the British tank formations from trying to finish off the Afrika Korps when it was strung out between the minefields and Alam Halfa.[44] Friedrich von Mellenthin in Panzer Battles painted a dramatic picture of Panzer divisions, paralysed by lack of fuel, under constant bombardment and awaiting a British onslaught.[45]

Montgomery pointed out that the Eighth Army was in a process of reformation with the arrival of new, untrained units and was not ready to take the offensive. Nor was his army yet prepared for a 1,600 mi (2,600 km) pursuit were they to break through, which had caused both sides to fail to end the desert campaign, after gaining tactical success. Montgomery did not want his tanks wasted on futile attacks against Rommel's anti-tank screen, something that had frequently happened in the past, handing the initiative to the Axis forces. Rommel complained to Kesselring, "The swine isn't attacking!".[46] Montgomery's refusal kept his forces intact and the Eighth Army accumulated supplies for the offensive in October that came to be known as the Second Battle of El Alamein.[47]

Notes

- "In the centre of the British front a good Italian division, the Bologna, delivered a strong attack on the Ruweisat Ridge, and a considerable counter-attack was required to expel it from the footing it gained."[35]

Citations

- Watson (2007), p. 14

- Buffetaut pp. 90–91

- Playfair, 2004, p. 379

- Hinsley, pp. 418–419

- Playfair, 2004, pp. 338, 379

- Playfair, 2004, p. 392

- Hinsley, p. 412

- Hinsley, pp. 410–411

- Carver p. 48

- Fraser p. 351

- Playfair, 2004, p. 382

- Watson p. 12

- Fraser pp. 355–357

- Carver p. 49

- Stumpf 2001, p. 755.

- Smith, Kevin D. (July–August 2002). "The contribution of Intelligence at the Battle of Alam Halfa". Military Review. pp. 74–77.

Only a few days before the battle, Ultra confirmed that Montgomery's estimate of Rommel's intentions was correct.

- Harper, Glyn (2017). The battle for North Africa : El Alamein and the turning point for World War II. p. 95. ISBN 9780253031433.

- Watson p. 10

- Playfair, 2004, p. 384

- Fraser p. 354

- Fraser pp. 354–355

- Walker 1967 p. 45

- Roberts and BayerleinArchived 2007-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Playfair, 2004, p. 387

- Watson p. 13

- Lewin p. 157

- Playfair, 2004, p. 386

- Carver p. 58

- Cappellano, p. 35

- Jentz. Panzertruppen 1

- Liddell Hart 1970 p.

- Carver p. 62

- German Attack at El Alamein: August 31 – September 5, 1942" from Tactical and Technical Trends

- Murphy, 1966, p. 358

- Falls 1948, p. 262

- Lightbody, p. 142

- Fraser p. 359

- Carver p. 67

- Playfair, 2004, p. 388

- Barr, pp. 245–246

- Carver p. 70; Playfair, 2004, p. 389

- Playfair, 2004, p. 389

- Buffetaut p. 90

- Carver p. 181

- Mellenthin 1956, p. 103.

- Walker, 1967, p. 180

- Fraser p. 360

References

- Barr, N. (2005). Pendulum of War: The Three Battles of Alamein. Woodstock: Overlook Press. ISBN 1-58567-655-1.

- Beretta, Davide (1997). Batterie semoventi, alzo zero: quelli di El Alamein [Self-propelled Batteries, Point Blank of El Alamein]. Milano: Mursia. ISBN 88-425-2179-5.

- Boog, H.; Rahn, R.; Stumpf, R.; Wegner, B. (2001). "(Part V) The War in the Mediterranean Area 1942–1943: Operations in North Africa and the Central Mediterranean. 2. The Battle of Alam Halfa (30 August–6 September 1942)". In Osers, E. (ed.). The Global War: Widening of the Conflict into a World War and the Shift of the Initiative 1941–1943 (Edited by the Militărgeschichtliches Forschungsamt [Research Institute for Military History] Potsdam, Germany). Germany and the Second World War. VI. Translated by Osers, E.; Brownjohn, J.; Crampton, P.; Willmot, L. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 748–764. ISBN 0-19-822888-0.

- Buffetaut, Yves (1995). Operation Supercharge-La seconde bataille d'El Alamein [Operation Supercharge: The Second Battle of El Alamein]. Les grandes batailles de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Collection hors-série Militaria (in French). Paris: Histoire Et Collections. OCLC 464158829.

- Cappellano, Filippo (2012). Italian Medium Tanks: 1939–45. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84908-775-9.

- Carver, Michael (1962). El Alamein. Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-84022-220-4.

- Conetta, Carl; Knight, Charles; Unterseher, Lutz (September 1997). "Defensive Military Structures in Action: Historical Examples". Confidence-Building Defense: A Comprehensive Approach to Security & Stability in the New Era, Study Group on Alternative Security Policy and Project on Defense Alternatives. 1994. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Commonwealth Institute. OCLC 45377322.

- Cox, Sebastian; Gray, Peter (2002). Air Power History: Turning Points from Kitty Hawk to Kosovo. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-8257-8.

- Fraser, David (1993). Knight's Cross: A Life of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-638384-X.

- Falls, Cyril (1948). "Aftermath of War: The Eights Army from Alamein to Sangro". The Illustrated London News. The Illustrated London News & Sketch. 212 (5672–5684). ISSN 0019-2422.

- Hinsley, F. H.; Thomas, E. E.; Ransom, C. F. G.; Knight, R. C. (1981). British Intelligence in the Second World War. Its influence on Strategy and Operations. II. London: HMSO. ISBN 0-11-630934-2.

- Lightbody, Bradley (2004). The Second World War: Ambitions to Nemesis. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22404-7.

- Mellenthin, Friedrich Wilhem von (1956). Panzer Battles: A Study of the Employment of Armour in the Second World War. Translated by Turner, L. C. F. New York: Ballantine. OCLC 638823584.

- Murphy, W. E. (1966) [1966]. 2nd New Zealand Divisional Artillery. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945. Wellington: War History Branch. OCLC 226971027.

- Naveh, Shimon (1997) [1991]. In Pursuit of Military Excellence; The Evolution of Operational Theory. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-4727-6.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; with Flynn RN, Captain F. C.; Molony, Brigadier C. J. C. & Gleave, Group Captain T. P. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1960]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: British Fortunes reach their Lowest Ebb (September 1941 to September 1942). History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. III. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-067-X.

- Roberts, Major-General G. P. B.; Bayerlein, Generalleutnant Fritz. Basil Liddell Hart (ed.). "U.S. Combat Studies Institute Battle Report: Alam Halfa". Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- Walker, Ronald (1967). "Chapter 11, Summary of the Battle". Alam Halfa and Alamein. The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945. New Zealand Historical Publications Branch, Wellington. pp. 165–181. OCLC 893102.

- Watson, Bruce Allen (2007) [1999]. Exit Rommel. Mechanicsburg PA: Stackpole. ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6.

Further reading

- Montanari, Mario (2007). The Three Battles of El Alamein (June–November 1942 Parte Prima. Translated by Doré, Dominique (online scan abbr. trans, Le operazioni in Africa Settentrionale vol III ed.). Roma: L'Ufficio Storico dello Stato Maggiore dell'Esercito. ISBN 978-88-87940-79-4. Retrieved 11 December 2019 – via issuu.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Alam el Halfa. |