Brahmaputra River

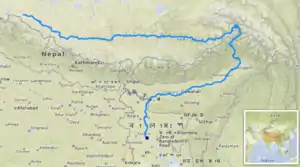

The Brahmaputra (/ˌbrɑːməˈpuːtrə/), called Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet, Siang/Dihang River in Arunachal Pradesh and Luit, Dilao[2] in Assam, is a trans-boundary river which flows through Tibet, India and Bangladesh.[lower-alpha 1] It is the 9th largest river in the world by discharge, and the 15th longest.

| Brahmaputra Dilao, Lauhitya | |

|---|---|

The Brahmaputra in Guwahati, Assam, India | |

| |

| Etymology | Sanskrit; Brahmaputra for Son (Putra) of Brahmā |

| Native name | ব্রহ্মপুত্র নদ |

| Location | |

| Countries | |

| Autonomous Region | Tibet |

| Cities | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Angsi Glacier, Manasarovar |

| • location | Himalayas |

| • coordinates | 30°23′N 82°0′E |

| • elevation | 5,210 m (17,090 ft) |

| Mouth | Ganges |

• location | Ganges Delta |

• coordinates | 25°13′24″N 89°41′41″E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | Mapped 3,969 km (2,466 mi).[1] Actual 4,696 km (2,918 mi). |

| Basin size | 712,035 km2 (274,918 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 19,800 m3/s (700,000 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 100,000 m3/s (3,500,000 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Lhasa River, Nyang River, Parlung Zangbo, Lohit River, Dhansiri River, Kolong River |

| • right | Kameng River, Manas River, Beki River, Raidak River, Jaldhaka River, Teesta River, Subansiri River |

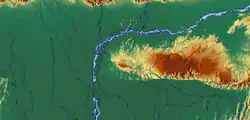

With its origin in the Manasarovar Lake region, near the Mount Kailash, located on the northern side of the Himalayas in Burang County of Tibet as the Yarlung Tsangpo River,[1] it flows along southern Tibet to break through the Himalayas in great gorges (including the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon) and into Arunachal Pradesh (India).[4] It flows southwest through the Assam Valley as Brahmaputra and south through Bangladesh as the Jamuna (not to be mistaken with Yamuna of India). In the vast Ganges Delta, it merges with the Padma, the popular name of the river Ganges in Bangladesh, and finally, after merging with Padma, it becomes the Meghna and from here, it flows as Meghna river before emptying into the Bay of Bengal.[5]

About 4,696 km (2,918 mi)[1] long, the Brahmaputra is an important river for irrigation and transportation in the region. The average depth [perhaps width?] of the river is 140 m (450 ft) and maximum depth is 370 m (1,200 ft). The river is prone to catastrophic flooding in the Spring when the Himalayan snow melts. The average discharge of the river is about 19,800 m3/s (700,000 cu ft/s),[4] and floods reach about 100,000 m3/s (3,500,000 cu ft/s).[6] It is a classic example of a braided river and is highly susceptible to channel migration and avulsion.[7] It is also one of the few rivers in the world that exhibits a tidal bore. It is navigable for most of its length.

The river drains the Himalayan east of the Indo-Nepal border, south-central portion of the Tibetan plateau above the Ganga basin, south-eastern portion of Tibet, the Patkai-Bum hills, the northern slopes of the Meghalaya hills, the Assam plains, and the northern portion of Bangladesh. The basin, especially south of Tibet, is characterized by high levels of rainfall. Kangchenjunga (8,586 m) is the only peak above 8,000 m, hence is the highest point within the Brahmaputra basin.

The Brahmaputra's upper course was long unknown, and its identity with the Yarlung Tsangpo was only established by exploration in 1884–86. This river is often called the Tsangpo-Brahmaputra river.

The lower reaches are sacred to Hindus. While most rivers on the Indian subcontinent have female names, this river has a rare male name. Brahmaputra means "son of Brahma" in Sanskrit.[8]

Geography

Tibet

The upper reaches of the Brahmaputra River, known as the Yarlung Tsangpo from the Tibetan language, originates on the Angsi Glacier, near Mount Kailash, located on the northern side of the Himalayas in Burang County of Tibet. The source of the river was earlier thought to be on the Chemayungdung glacier, which covers the slopes of the Himalayas about 97 km (60 mi) southeast of Lake Manasarovar in southwestern Tibet. The river is 3,969 km (2,466 mi) long, and its drainage area is 712,035 km2 (274,918 sq mi) according to the new findings, while previous documents showed its length varied from 2,916 km (1,812 mi) to 3,364 km (2,090 mi)and its drainage area between 520,000 and 1.73 million km2. This finding has been given by Liu Shaochuang, a researcher with the Institute of Remote Sensing Applications under the analysis using expeditions and satellite imagery from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).[1][9]

From its source, the river runs for nearly 1,100 km (680 mi) in a generally easterly direction between the main range of the Himalayas to the south and the Kailas Range to the north.

In Tibet, the Tsangpo receives a number of tributaries. The most important left-bank tributaries are the Raka Zangbo (Raka Tsangpo), which joins the river west of Xigazê (Shigatse), and the Lhasa (Kyi), which flows past the Tibetan capital of Lhasa and joins the Tsangpo at Qüxü. The Nyang River joins the Tsangpo from the north at Zela (Tsela Dzong). On the right bank, a second river called the Nyang Qu (Nyang Chu) meets the Tsangpo at Xigazê.

After passing Pi (Pe) in Tibet, the river turns suddenly to the north and northeast and cuts a course through a succession of great narrow gorges between the mountainous massifs of Gyala Peri and Namcha Barwa in a series of rapids and cascades. Thereafter, the river turns south and southwest and flows through a deep gorge (the "Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon") across the eastern extremity of the Himalayas with canyon walls that extend upward for 5,000 m (16,000 ft) and more on each side. During that stretch, the river enters northern Arunachal Pradesh state in northeastern India, where it is known as the Dihang (or Siang) River, and turns more southerly.

Assam and adjoining region

The Yarlung Tsangpo enters the state of Arunachal Pradesh in India, where it is called Siang. It makes a very rapid descent from its original height in Tibet and finally appears in the plains, where it is called Dihang. It flows for about 35 km (22 mi) southward after which, it is joined by the Dibang River and the Lohit River at the head of the Assam Valley. Below the Lohit, the river is called Brahmaputra and Doima (mother of water) and Burlung-Buthur by native Bodo tribals, it then enters the state of Assam, and becomes very wide—as wide as 20 km (12 mi) in parts of Assam.

The Dihang, winding out of the mountains, turns towards the southeast and descends into a low-lying basin as it enters northeastern Assam state. Just west of the town of Sadiya, the river again turns to the southwest and is joined by two mountain streams, the Lohit, and the Dibang. Below that confluence, about 1,450 km (900 mi) from the Bay of Bengal, the river becomes known conventionally as the Brahmaputra ("Son of Brahma"). In Assam, the river is mighty, even in the dry season, and during the rains, its banks are more than 8 km (5.0 mi) apart. As the river follows its braided 700 km (430 mi) course through the valley, it receives several rapidly flowing Himalayan streams, including the Subansiri, Kameng, Bhareli, Dhansiri, Manas, Champamati, Saralbhanga, and Sankosh Rivers. The main tributaries from the hills and from the plateau to the south are the Burhi Dihing, the Disang, the Dikhu, and the Kopili.

Between Dibrugarh and Lakhimpur Districts, the river divides into two channels—the northern Kherkutia channel and the southern Brahmaputra channel. The two channels join again about 100 km (62 mi) downstream, forming the Majuli island, which is the largest river island in the world.[10] At Guwahati, near the ancient pilgrimage centre of Hajo, the Brahmaputra cuts through the rocks of the Shillong Plateau, and is at its narrowest at 1 km (1,100 yd) bank-to-bank. The terrain of this area made it logistically ideal for the Battle of Saraighat, the military confrontation between the Mughal Empire and the Ahom Kingdom in March 1671. The first combined railroad/roadway bridge across the Brahmaputra was constructed at Saraighat. It was opened to traffic in April 1962.

The environment of the Brahmaputra floodplains in Assam have been described as the Brahmaputra Valley semi-evergreen forests ecoregion.

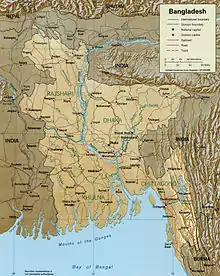

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, the Brahmaputra is joined by the Teesta River (or Tista), one of its largest tributaries. Below the Tista, the Brahmaputra splits into two distributary branches. The western branch, which contains the majority of the river's flow, continues due south as the Jamuna (Jomuna) to merge with the lower Ganga, called the Padma River (Pôdda). The eastern branch, formerly the larger, but now much smaller, is called the lower or Old Brahmaputra (Brommoputro). It curves southeast to join the Meghna River near Dhaka. The Padma and Meghna converge near Chandpur and flow out into the Bay of Bengal. This final part of the river is called Meghna.

The Brahmaputra enters the plains of Bangladesh after turning south around the Garo Hills below Dhuburi, India. After flowing past Chilmari, Bangladesh, it is joined on its right bank by the Tista River and then follows a 240 km (150-mi) course due south as the Jamuna River. (South of Gaibanda, the Old Brahmaputra leaves the left bank of the mainstream and flows past Jamalpur and Mymensingh to join the Meghna River at Bhairab Bazar.) Before its confluence with the Ganga, the Jamuna receives the combined waters of the Baral, Atrai, and Hurasagar Rivers on its right bank and becomes the point of departure of the large Dhaleswari River on its left bank. A tributary of the Dhaleswari, the Buriganga ("Old Ganga"), flows past Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, and joins the Meghna River above Munshiganj.

The Jamuna joins with the Ganga north of Goalundo Ghat, below which, as the Padma, their combined waters flow to the southeast for a distance of about 120 km (75 mi). After several smaller channels branch off to feed the Ganga-Brahmaputra delta to the south, the main body of the Padma reaches its confluence with the Meghna River near Chandpur and then enters the Bay of Bengal through the Meghna estuary and lesser channels flowing through the delta. The growth of the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta is dominated by tidal processes.

The Ganga Delta, fed by the waters of numerous rivers, including the Ganga and Brahmaputra, is 59,570 square kilometres (23,000 sq mi) the largest river deltas in the world.[11]

Basin characteristics

The basin of the Brahmaputra river is 651 334 km2 and it is a good example of a braided river and meanders quite a bit and frequently forms temporary sand bars. A region of significant tectonic activity has developed in the Jamuna River and is associated with the Himalayan uplift and development of the Bengal foredeep. Several researchers have hypothesized that the underlying structural control on the location of the major river systems of Bangladesh. A zone of 'structural weakness' along the present course of the Ganga-Jamuna-Padma Rivers due to either a subsiding trough or a fault at depth has been observed by Morgan and Melntire. (1959). Scijmonsbergen (1999) contends that width changes in the Jamuna may respond to these faults and they may also cause increased sedimentation upstream of the fault. He presented a few images to argue that a fault downstream of the Bangabandhu Multipurpose Bridge has affected channel migration. Huge accumulations of sediment that have been fed from Himalayan erosion has been produced due to the deepening of the Bengal Basin, with the thickness of sediment above the Precambrian basement increasing from a few hundred meters in the shelf region to over 18 km in the Bengal foredeep to the south. The tectonic and climatic context for the large water and sediment discharges in the rivers of Bangladesh was set by the ongoing subsidence in the Bengal Basin, combined with high rates of Himalayan uplift. The control of uplift and subsidence is, however, clear. The courses of the Jamuna and Ganga Rivers are first-order controls due to the fact that they are most influenced by the uplifted Plcistoccnc terraces of the Barind and Madhupur tracts.[12]

Hydrology

The Ganga-Brahmaputra system has the third-greatest average discharge of the world's rivers—roughly 30,770 m3 (1,086,500 ft3) per second; and the river Brahmaputra alone supplies about 19,800 m3 (700,000 ft3) per second of the total discharge. The rivers' combined suspended sediment load of about 1.87 billion tonnes (1.84 billion tons) per year is the world's highest.[4][13]

In the past, the lower course of the Brahmaputra was different and passed through the Jamalpur and Mymensingh districts. In an 8.8 magnitude earthquake on 2 April 1762, however, the main channel of the Brahmaputra at Bhahadurabad point was switched southwards and opened as Jamuna due to the result of tectonic uplift of the Madhupur tract.[14]

Climate

Rising temperature is one of the major cause of snow-melting at the upper Brahmaputra catchment.[15] The discharge of the river Brahmaputra is highly affected by the melting of snow at the upper part of its catchment. Then of river flow due to the melting of snow in the river Brahmaputra basin affects the downstream discharge of the river. This increase in discharge due to the significant retreat of snow gives rise to severe catastrophic problems such as flood and erosion. The weather is a cold and harsh climate.

Discharge

The Brahmaputra River is characterized by its significant rates of sediment discharge, the large and variable flows, along with its rapid channel aggradations and accelerated rates of basin denudation. Over time, the deepening of the Bengal Basin caused by erosion will result in the increase in hydraulic radius, and hence allowing for the huge accumulation of sediments fed from the Himalayan erosion by efficient sediment transportation. The thickness of the sediment accumulated above the Precambrian basement has increased over the years from a few hundred meters to over 18 km in the Bengal fore-deep to the south. The ongoing subsidence of the Bengal Basin and the high rate of Himalayan uplift continues to contribute to the large water and sediment discharges of fine sand and silt, with 1% clay, in the Brahmaputra River.

Climatic change plays a crucial role in affecting the basin hydrology. Throughout the year, there is a significant rise in hydrograph, with a broad peak between July and September. The Brahmaputra River experiences two high-water seasons, one in early summer caused by snowmelt in the mountains, and one in late summer caused by runoff from monsoon rains. The river flow is strongly influenced by snow and ice melting of the glaciers, which are located mainly on the eastern Himalaya regions in the upstream parts of the basin. The snow and glacier melt contribution to the total annual runoff is about 27%, while the annual rainfall contributes to about 1.9m and 19,830 m3 /s of discharge. The highest recorded daily discharge in the Brahmaputra at Pandu was 72,726 m3 /s August 1962 while the lowest was 1,757 m3 /s in February 1968. The increased rates of snow and glacial melt are likely to increase summer flows in some river systems for a few decades, followed by a reduction in flow as the glaciers disappear and snowfall diminishes. This is particularly true for the dry season when water availability is crucial for the irrigation systems.

Floodplain evolution

The course of the Brahmaputra River has changed drastically in the past two and a half centuries, moving its river course westwards for a distance of about 80 km (50 mi), leaving its old river course, appropriately named the old Brahmaputra river, behind. In the past, the floodplain of the old river course had soils which were more properly formed compared to graded sediments on the operating Jamuna river.This change of river course resulted in modifications to the soil-forming process, which include acidification, the breakdown of clays and buildup of organic matter, with the soils showing an increasing amount of biotic homogenization, mottling, the coating around Peds and maturing soil arrangement, shape and pattern. In the future, the consequences of local ground subsidence coupled with flood prevention propositions, for instance, localised breakwaters, that increase flood-plain water depths outside the water breakers, may alter the water levels of the floodplains. Throughout the years, bars, scroll bars, and sand dunes are formed at the edge of the flood plain by deposition. The height difference of the channel topography is often not more than 1m-2m. Furthermore, flooding over the history of the river has caused the formation of river levees due to deposition from the overbank flow. The height difference between the levee top and the surrounding floodplains is typically 1m along small channels and 2-3m along major channels. Crevasse splay, a sedimentary fluvial deposit which forms when a stream breaks its natural or artificial levees and deposits sediment on a floodplain, are often formed due to a breach in the levee, forming a lobe of sediments which progrades onto the adjacent floodplain. Lastly, flood basins are often formed between the levees of adjacent rivers.

Flooding

During the monsoon season (June–October), floods are a very common occurrence. Deforestation in the Brahmaputra watershed has resulted in increased siltation levels, flash floods, and soil erosion in critical downstream habitat, such as the Kaziranga National Park in middle Assam. Occasionally, massive flooding causes huge losses to crops, life, and property. Periodic flooding is a natural phenomenon which is ecologically important because it helps maintain the lowland grasslands and associated wildlife. Periodic floods also deposit fresh alluvium, replenishing the fertile soil of the Brahmaputra River Valley. Thus flooding, agriculture, and agricultural practices are closely connected.[16][17][18]

The effects of flooding can be devastating and cause significant damage to crops and houses, serious bank erosive with consequent loss of homesteads, school and land, and loss of many lives, livestock, and fisheries. During the 1998 flood, over 70% of the land area of Bangladesh was inundated, affecting 31 million people and 1 million homesteads. In the 1998 flood which had an unusually long duration from July to September, claimed 918 human lives and was responsible for damaging 16 00 and 6000 km of roads and embankments respectively, and affecting 6000 km2 of standing crops. The 2004 floods, over 25% of the population of Bangladesh or 36 million people, were affected by the floods; 800 lives were lost; 952 000 houses were destroyed and 1.4 million were badly damaged; 24 000 educational institutions were affected including the destruction of 1200 primary schools, 2 million governments and private tube wells were affected, over 3 million latrines were damaged or washed away, this increases the risks of waterborne diseases including diarrhea and cholera. Also, 1.1 M ha of the rice crop was submerged and lost before it could be harvested, with 7% of the yearly aus (early season) rice crop lost; 270 000 ha of grazing land was affected, 5600 livestock perished together with 254 00 poultry and 63 MT of lost fish production.

Flood-control measures are taken by the water resource department and the Brahmaputra Board, but until now the flood problem remains unsolved. At least a third of the land of Majuli island has been eroded by the river. Recently, it is suggested that a highway protected by concrete mat along the river bank and excavation of the river bed can curb this menace. This project, named the Brahmaputra River Restoration Project, is yet to be implemented by the government. Recently the Central Government approved the construction of Brahmaputra Express Highways.

Channel morphology

The course of the Brahmaputra River has changed dramatically over the past 250 years, with evidence of large-scale avulsion, in the period 1776–1850, of 80 km from east of the Madhupur tract to the west of it. Prior to 1843, the Brahmaputra flowed within the channel now termed the "old Brahmaputra". The banks of the river are mostly weakly cohesive sand and silts, which usually erodes through large scale slab failure, where previously deposited materials undergo scour and bank erosion during flood periods. Presently, the river's erosion rate has decreased to 30m per year as compared to 150m per year from 1973 to 1992. This erosion has, however, destroyed so much land that it has caused 0.7 million people to become homeless due to loss of land.

Several studies have discussed the reasons for the avulsion of the river into its present course, and have suggested a number of reasons including tectonic activity, switches in the upstream course of the Teesta River, the influence of increased discharge, catastrophic floods and river capture into an old river course. From an analysis of maps of the river between 1776 and 1843, it was concluded in a study that the river avulsion was more likely gradual than catastrophic and sudden, and may have been generated by bank erosion, perhaps around a large mid-channel bar, causing a diversion of the channel into the existing floodplain channel.

The Brahmaputra channel is governed by the peak and low flow periods during which its bed undergoes tremendous modification. The Brahmaputra's bank line migration is inconsistent with time. The Brahmaputra river bed has widened significantly since 1916 and appears to be shifting more towards the south than towards the north. Together with the contemporary slow migration of the river, the left bank is being eroded away faster than the right bank.[19]

River engineering

The Brahmaputra River experiences high levels of bank erosion (usually via slab failure) and channel migration caused by its strong current, lack of riverbank vegetation, and loose sand and silt which compose its banks. It is thus difficult to build permanent structures on the river, and protective structures designed to limit the river's erosional effects often face numerous issues during and after construction. In fact, a 2004 report[20] by the Bangladesh Disaster and Emergency Sub-Group (BDER) has stated that several of such protective systems have 'just failed'. However, some progress has been made in the form of construction works which stabilize sections of the river, albeit the need for heavy maintenance. The Bangabandhu Bridge, the only bridge to span the river's major distributary, the Jamuna, was thus opened in June 1998. Constructed at a narrow braid belt of the river, it is 4.8 km long with a platform 18.5 m wide, and it is used to carry railroad traffic as well as gas, power and telecommunication lines. Due to the variable nature of the river, the prediction of the river's future course is crucial in planning upstream engineering to prevent flooding on the bridge.

China had built the Zangmu Dam in the upper course of the Brahmaputra River in the Tibet region and it was operationalised on 13 October 2015.[21]

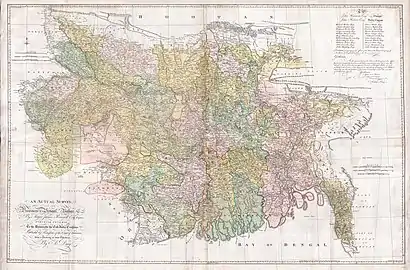

History

Earlier history

The Kachari group called the river "Dilao", "Tilao".[22] Early Greek accounts of Curtius and Strabo give its name as Dyardanes (Ancient greek Δυαρδάνης) and Oidanes.[23] In the past, the course of the lower Brahmaputra was different and passed through the Jamalpur and Mymensingh districts. Some water still flows through that course, now called the Old Brahmaputra, as a distributary of the main channel.

A question about the river system in Bangladesh is when and why the Brahmaputra changed its main course, at the site of the Jamuna and the "Old Brahmaputra" fork that can be seen by comparing modern maps to historic maps before the 1800s.[24] The Brahmaputra likely flowed directly south along its present main channel for much of the time since the last glacial maximum, switching back and forth between the two courses several times throughout the Holocene.

One idea about the most recent avulsion is that the change in the course of the main waters of the Brahmaputra took place suddenly in 1787, the year of the heavy flooding of the river Tista.

In the middle of the 18th century, at least three fair-sized streams flowed between the Rajshahi and Dhaka Divisions, viz., the Daokoba, a branch of the Tista, the Monash or Konai, and the Salangi. The Lahajang and the Elengjany were also important rivers. In Renault's time, the Brahmaputra as a first step towards securing a more direct course to the sea by leaving the Mahdupur Jungle to the east began to send a considerable volume of water down the Jinai or Jabuna from Jamalpur into the Monash and Salangi. These rivers gradually coalesced and kept shifting to the west till they met the Daokoba, which was showing an equally rapid tendency to cut towards the east. The junction of these rivers gave the Brahmaputra a course worthy of her immense power, and the rivers to right and left silted up. In Renault's Altas they very much resemble the rivers of Jessore, which dried up after the hundred-mouthed Ganga had cut her new channel to join the Meghna at the south of the Munshiganj subdivision.

In 1809, Francis Buchanan-Hamilton wrote that the new channel between Bhawanipur and Dewanranj "was scarcely inferior to the mighty river, and threatens to sweep away the intermediate country". By 1830, the old channel had been reduced to its present insignificance. It was navigable by country boats throughout the year and by launches only during rains, but at the point as low as Jamalpur it was formidable throughout the cold weather. Similar was the position for two or three months just below Mymensingh also.

International cooperation

The waters of the River Brahmaputra are shared by China, India, and Bangladesh. In the 1990s and 2000s, there was repeated speculation that mentioned Chinese plans to build a dam at the Great Bend, with a view to diverting the waters to the north of the country. This has been denied by the Chinese government for many years.[25] At the Kathmandu Workshop of Strategic Foresight Group in August 2009 on Water Security in the Himalayan Region, which brought together in a rare development leading hydrologists from the basin countries, the Chinese scientists argued that it was not feasible for China to undertake such a diversion.[26] However, on 22 April 2010, China confirmed that it was indeed building the Zangmu Dam on the Brahmaputra in Tibet,[25] but assured India that the project would not have any significant effect on the downstream flow to India.[27] This claim has also been reiterated by the Government of India, in an attempt to assuage domestic criticism of Chinese dam construction on the river, but is one that remains hotly debated.[28] Recent years have seen an intensification of grassroots opposition, especially in the state of Assam, against Chinese upstream dam building, as well as growing criticism of the Indian government for its perceived failure to respond appropriately to Chinese hydropower plans.[29]

In a meeting of scientists at Dhaka at 2010, 25 leading experts from the basin countries issued a Dhaka Declaration on Water Security[30] calling for the exchange of information in low-flow periods, and other means of collaboration. Even though the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention does not prevent any of the basin countries from building a dam upstream, customary law offers some relief to the lower riparian countries. There is also the potential for China, India, and Bangladesh to cooperate on transboundary water navigation.

Significance to people

The lives of many millions of Indian and Bangladeshi citizens are reliant on the Brahmaputra river. Its delta is home to 130 million people and 600 000 people live on the riverine islands. These people rely on the annual 'normal' flood to bring moisture and fresh sediments to the floodplain soils, hence providing the necessities for agricultural and marine farming. In fact, two of the three seasonal rice varieties (aus and aman) cannot survive without the floodwater. Furthermore, the fish caught both on the floodplain during flood season and from the many floodplain ponds are the main source of protein for many rural populations.

Development

Dams and hydropower projects

Bridges

India

Current bridges

From east to west till Parshuram Kund, then from southwest to northeast from Parshuram Kund to Patum, finally from east to southwest from Parshuram Kund to Burhidhing:

- Sankosh Bridge near Gossaigaon on tributary of Brahmaputra on West Bengal-Assam border. 675 meters.

- Sankosh Railway Bridge near Gossaigaon on tributary of Brahmaputra on West Bengal-Assam border. 675 meters

- Chilarai Bridge near Rupsi Airport on tributary of Brahmaputra. 625 meters

- Golakganj Bridge just south of Chilarai Bridge near Rupsi Airport on tributary of Brahmaputra. 575 meters.

- Old Saraighat Bridge, road and rail bridge near Guwahati in Assam. 1.483 km

- New Saraighat Bridge, road bridge near Guwahati in Assam. 1.521 km

- Kolia Bhomora Setu, road bridge near Tezpur in Assam, 3.015 km

- Naranarayan Setu, road and rail bridge near Bongaigaon in Assam, 2.284 km

- Bogibeel Bridge, road and rail bridge near Dibrugarh in Assam, 4.94 km

- Dhola–Sadiya Bridge (Bhupen Hazarika Bridge), road bridge on Brahmaputra's River Lohit tributary near Chongkham in Assam, 9.15 km long

- Dibang River Bridge, road bridge on Brahmaputra's River Lohit tributary in Arunachal Pradesh, 6.2 km long connects Bomjir and Malek

- Parshuram Kund road bridge on Brahmaputra's Lohit river tributary in Arunachal Pradesh, 2.6 km long

- Silluk-Dambuk Bridge, road bridge in Arunachal Pradesh on Brahmaputra's Lohit river tributary between Silluk-Dambuk. 4.4 km long.

- Ranaghat Bridge on Brahmaputra at Pasighat in Arunachal Pradesh. 3.3 km long

- Patum Bridge on Brahmaputra's tributary near Aalo (formerly Along) in Arunachal Pradesh. 1.681 km

- Wakro Bridge, road bridge on Brahmaputra's tributary Lohit river in Arunachal Pradesh, 1.444 km

- Nao-Dihing Bridge road bridge on Brahmaputra's tributary Dihing river near Margherita, Assam and Ledo in Assam. 2.052 km long

- NEEPCO Bridge road bridge on Brahmaputra's tributary Buriding river near Jeypore, Assam. 1.936 km long

- Naharkatiya Bridge road bridge on Brahmaputra's tributary Dihing river near Naharkatiya in Assam. 961 meters long

- Burhidhing Railway Bridge road bridge on Brahmaputra's tributary Dihing river near Khowang in Assam. 916 meters long.

Planned bridges

In addition to Dhubri-Phulbari bridge, five new bridges were announced in December 2017 by India's Highway Minister Nitin Gadkari.[31][32] From east to west:

- Dhubri-Phulbari bridge, road and rail bridge in Assam, near tri-junction of east Meghalaya, east Assam and north Bangladesh[31][32] 19.00 km

- Guwahati-North Guwahati[31][32] 1.90 km

- Bhomoraguri-Tezpur Bridge between Bhomoraguri-Tezpur in Assam[32] 3.249 km

- Numaligarh-Gohpur Bridge between Gohpur-Numaligarh in Assam[31][32] 4.41 km

- Jorhat-Nematighat bridge between Jorhat-Tezpur in Assam[31][32] 4.0 km

- Disangmukh-Tekeliphuta Bridge between Disangmukh-Tekeliphuta near Sivasagar in Assam[31][32] 2.8 km

- Louit-Khablu Bridge (perhaps it is one of the bridge with different name among the above?)[31] 5.29 km

Under-river tunnel

- Gohpur–Numaligarh under-river tunnel[33]

Bangladesh

- Present bridges in Bangladesh

- Bangabandhu Bridge (formerly Jamuna Bridge), road and rail bridge

- Padma Bridge, road and rail bridge on Padma River tributary of Brahmaputra

- Lalon Shah Bridge road bridge on Padma River tributary of Brahmaputra

- Hardinge Bridge, rail bridge on Padma River next to Lalon Shah Bridge

- Planned bridges in Bangladesh

- Gaibandha-Bakshiganj Bridge, road and rail bridge to connect existing rail and road heads at Gaibandha-Bakshiganj on ether side of the river

- Siraiganj-Tangail Bridge, road and rail bridge to connect existing rail and road heads at Siraiganj-Tangail on ether side of the river

See also

- BrahMos (missile) – A missile named partly after the Brahmaputra River

- Brahmaputra-class frigate

- Dhola-Sadiya bridge

- List of rivers of Asia

- List of rivers of Assam

- List of rivers of Bangladesh

- List of rivers of China

- List of rivers of India

References

Notes

- As such, it is known by various names in the region: Assamese: লুইত luit [luɪt], ব্ৰহ্মপুত্ৰ নৈ Brohmoputro noi, ব্ৰহ্মপুত্ৰ নদ (the tatsama 'নদ' nod, masculine form of the tatsama 'নদী' nodi "river") Brohmoputro [bɹɔɦmɔputɹɔ]; Sanskrit: ब्रह्मपुत्र, IAST: Brahmaputra; Tibetan: ཡར་ཀླུངས་གཙང་པོ་, Wylie: yar klung gtsang po Yarlung Tsangpo; simplified Chinese: 布拉马普特拉河; traditional Chinese: 布拉馬普特拉河; pinyin: Bùlāmǎpǔtèlā Hé. It is also called Tsangpo-Brahmaputra and red river of India (when referring to the whole river including the stretch within the Tibet Autonomous Region).[3]

- "Scientists pinpoint sources of four major international rivers". Xinhua News Agency. 22 August 2011. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- Boruah, Sanjib (1999). India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality.

-

Michael Buckley (30 March 2015). "The Price of Damming Tibet's Rivers". The New York Times. p. A25. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

Two of the continent’s wildest rivers have their sources in Tibet: the Salween and the Brahmaputra. Though they are under threat from retreating glaciers, a more immediate concern is Chinese engineering plans. A cascade of five large dams is planned for both the Salween, which now flows freely, and the Brahmaputra, where one dam is already operational.

- "Brahmaputra River". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- "Brahmaputra River Flowing Down From Himalayas Towards Bay of Bengal". Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- "Water Resources of Bangladesh". FAO. Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- Catling, David (1992). Rice in deep water. International Rice Research Institute. p. 177. ISBN 978-971-22-0005-2. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 80.

- "China maps Brahmaputra source, course". Assam Tribune. 24 August 2011. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- Majuli, River Island. "Largest river island". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- Singh, Vijay P.; Sharma, Nayan; C. Shekhar; P. Ojha (2004). The Brahmaputra Basin Water Resources. Springer. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-4020-1737-7. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Gupta, Avijit (2008). Large Rivers: Geomorphology and Management. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-0-470-72371-5. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- The Geography of India: Sacred and Historic Places. Britannica Educational Publishing. 2010. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-1-61530-202-4. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- Suess, Eduard (1904). The face of the earth: (Das antlitz der erde). Clarendon press. pp. 50–. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Barman, Swapnali; Bhattacharjya, R. K. (2015). "Change in snow cover area of Brahmaputra river basin and its sensitivity to temperature". Environmental Systems Research. 4. doi:10.1186/s40068-015-0043-0.

- Das, D.C. 2000. Agricultural Landuse and Productivity Pattern in Lower Brahmaputra valley (1970–71 and 1994–95). PhD Thesis, Department of Geography, North Eastern Hill University, Shillong.

- Mipun, B.S. 1989. Impact of Migrants and Agricultural Changes in the Lower Brahmaputra Valley : A Case Study of Darrang District. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Department of Geography, North Eastern Hill University, Shillong.

- Shrivastava, R.J.; Heinen, J.T. (2005). "Migration and Home Gardens in the Brahmaputra Valley, Assam, India". Journal of Ecological Anthropology. 9: 20–34. doi:10.5038/2162-4593.9.1.2.

- Gilfellon, George; Sarma, Jogendra; Gohain, K. (August 2003). "Channel and Bed Morphology of a Part of the Brahmaputra River in Assam". Journal of the Geological Society of India. 62.

- Monsoon Floods 2004: Post Flood Needs Assessment Summary Report (PDF). Bangladesh Disaster and Emergency Sub-Group (BDER) (Report). Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2004. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- "China operationalizes biggest dam on Brahmaputra in Tibet". The Times of India. 13 October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Syed, Dr. M.H; Bright, P.S. Assam General Knowledge. ISBN 9788171994519.

- Burnell, A. C.; Yule, Henry (24 October 2018). Hobson-Jobson: Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words And Phrases. Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-136-60332-7.

- e.g. Rennell, 1776; Rennel, 1787

- "China admits to Brahmaputra project". The Economic Times. 22 April 2010. Archived from the original on 26 April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- MacArthur Foundation, Asian Security Initiative Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Chinese dam will not impact the flow of Brahmaputra: Krishna". The Indian Express. 22 April 2010. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- BBC (20 March 2014). "Megadams: Battle on the Brahmaputra". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- Yeophantong, Pichamon (2017). "River activism, policy entrepreneurship and transboundary water disputes in Asia". Water International. 42 (2): 163–186. doi:10.1080/02508060.2017.1279041. S2CID 157181000.

- "The New Nation, Bangladesh, 17 January 2010". Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- Nitin Gadkari flags off cargo movement on Brahmaputra Archived 2 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Economic Times, 29 December 2017.

- Fencing to be over by December: Sonowal

- Chaturvedi, Amit, ed. (14 July 2020). "Centre gives in-principle approval for tunnel under the Brahmaputra amid tension with China: Report". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Press Information Bureau". www.pib.nic.in. Government of India. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

Citations

- Rahaman, M. M.; Varis, O. (2009). "Integrated Water Management of the Brahmaputra Basin: Perspectives and Hope for Regional Development". Natural Resources Forum. 33 (1): 60–75. doi:10.1111/j.1477-8947.2009.01209.x.

- Sarma, J N (2005). "Fluvial process and morphology of the Brahmaputra River in Assam, India". Geomorphology. 70 (3–4): 226–256. Bibcode:2005Geomo..70..226S. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2005.02.007.

- Ribhaba Bharali. The Brahmaputra River Restoration Project. Published in Assamese Pratidin, Amar Assam in October 2012.

Further reading

- Bibliography on Water Resources and International Law. Peace Palace Library

- Rivers of Dhemaji and Dhakuakhana

- Background to Brahmaputra Flood Scenario

- The Mighty Brahmaputra

- Principal Rivers of Assam

- "The Brahmaputra", a detailed study of the river by renowned writer Arup Dutta. (Published by National Book Trust, New Delhi, India)

- Émilie Crémin. Entre mobilité et sédentarité : les Mising, « peuple du fleuve », face à l'endiguement du Brahmapoutre (Assam, Inde du Nord-Est). Milieux et Changements globaux. Université Paris 8 Vincennes Saint-Denis, 2014. Français. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01139754

- My Trip of Mighty Brahmaputra (in Gujarati)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brahmaputra. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Brahmaputra. |