Boeing 727

The Boeing 727 is an American narrow-body airliner produced by Boeing Commercial Airplanes. After the heavy 707 quad-jet was introduced in 1958, Boeing addressed the demand for shorter flight lengths from smaller airports. On December 5, 1960, the 727 was launched with 40 orders each from United Airlines and Eastern Air Lines. The first 727-100 rolled out November 27, 1962, first flew on February 9, 1963, and entered service with Eastern on February 1, 1964.

| Boeing 727 | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| A stretched 727-200 of Iberia | |

| Role | Narrow-body airliner |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Boeing Commercial Airplanes |

| First flight | February 9, 1963[1] |

| Introduction | February 1, 1964, with Eastern Air Lines |

| Status | Limited to freighters and executive use[lower-alpha 1] |

| Primary users | Líneas Aéreas Suramericanas Kalitta Charters Total Linhas Aereas |

| Produced | 1962–1984 |

| Number built | 1,832[3] |

Boeing's only trijet is powered by Pratt & Whitney JT8D low-bypass turbofans below a T-tail, one on each side of the rear fuselage and a center one fed through an S-duct. It shares its six-abreast upper fuselage cross-section and cockpit with the 707. The 133 ft (40.5 m) long 727-100 typically carries 106 passengers in two classes over 2,250 nmi (4,170 km), or 129 in a single class. Launched in 1965, the stretched 727-200 flew in July 1967 and entered service with Northeast Airlines that December. The 20 ft (6.1 m) longer variant typically carries 134 passengers in two classes over 2,550 nmi (4,720 km), or 155 in a single class. Besides the airliner accommodation, a freighter and a Quick Change convertible version were offered.

The 727 was used for many domestic flights and on some international flights within its range. Airport noise regulations have led to hush kit installations. Its last commercial passenger flight was in January 2019. It was succeeded by the 757-200 and larger variants of the 737. As of May 2020, a total of 13 Boeing 727s (1× 727-100s and 12× -200s) were in commercial service with 6 airlines, plus one in government and private use. There have been 118 fatal incidents involving the Boeing 727. Production ended in September 1984 with 1,832 having been built.

Development

.jpg.webp)

The Boeing 727 design was a compromise among United Airlines, American Airlines, and Eastern Air Lines; each of the three had developed requirements for a jet airliner to serve smaller cities with shorter runways and fewer passengers.[4] United Airlines requested a four-engine aircraft for its flights to high-altitude airports, especially its hub at Stapleton International Airport in Denver, Colorado.[4] American Airlines, which was operating the four-engined Boeing 707 and Boeing 720, requested a twin-engined aircraft for efficiency. Eastern Airlines wanted a third engine for its overwater flights to the Caribbean, since at that time twin-engine commercial flights were limited by regulations to routes with 60-minute maximum flying time to an airport (see ETOPS). Eventually, the three airlines agreed on a trijet design for the new aircraft.[4]

In 1959, Lord Douglas, chairman of British European Airways (BEA), suggested that Boeing and de Havilland Aircraft Company (later Hawker Siddeley) work together on their trijet designs, the 727 and D.H.121 Trident, respectively.[5] The two designs had a similar layout, the 727 being slightly larger. At that time Boeing intended to use three Allison AR963 turbofan engines, license-built versions of the Rolls-Royce RB163 Spey used by the Trident.[6][7] Boeing and de Havilland each sent engineers to the other company's locations to evaluate each other's designs, but Boeing eventually decided against the joint venture.[8] De Havilland had wanted Boeing to license-build the D.H.121, while Boeing felt that the aircraft needed to be designed for the American market, with six-abreast seating and the ability to use runways as short as 4,500 feet (1,400 m).[9]

In 1960, Pratt & Whitney was looking for a customer for its new JT8D turbofan design study, based on its J52 (JT8A) turbojet,[10] while United and Eastern were interested in a Pratt & Whitney alternative to the RB163 Spey.[11] Once Pratt & Whitney agreed to go ahead with development of the JT8D, Eddie Rickenbacker, chairman of the board of Eastern, told Boeing that the airline preferred the JT8D for its 727s. Boeing had not offered the JT8D, as it was about 1,000 lb (450 kg) heavier than the RB163, though slightly more powerful; the RB163 was also further along in development than the JT8D. Boeing reluctantly agreed to offer the JT8D as an option on the 727, and it later became the sole powerplant.[12]

With high-lift devices[13] on its wing, the 727 could use shorter runways than most earlier jets (e.g. the 4800-ft runway at Key West International Airport).

Later 727 models were stretched to carry more passengers[14] and replaced earlier jet airliners such as the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8, as well as aging propeller airliners such as the DC-4, DC-6, DC-7, and the Lockheed Constellations on short- and medium-haul routes.

For over a decade, more 727s were built per year than any other jet airliner; in 1984, production ended with 1,832 built[3] and 1,831 delivered, the highest total for any jet airliner until the 737 surpassed it in the early 1990s.[15]

Design

The airliner's middle engine (engine 2) at the very rear of the fuselage gets air from an inlet ahead of the vertical fin through an S-shaped duct.[16] This S-duct proved to be troublesome in that flow distortion in the duct induced a surge in the centerline engine on the take-off of the first flight of the 727-100.[17] This was fixed by the addition of several large vortex generators in the inside of the first bend of the duct.

The 727 was designed for smaller airports, so independence from ground facilities was an important requirement. This led to one of the 727's most distinctive features: the built-in airstair that opens from the rear underbelly of the fuselage, which initially could be opened in flight.[13] Hijacker D. B. Cooper used this hatch when he parachuted from the back of a 727, as it was flying over the Pacific Northwest. Boeing subsequently modified the design with the Cooper vane so that the airstair could not be lowered in flight.[18] Another innovation was the auxiliary power unit (APU), which allowed electrical and air-conditioning systems to run independently of a ground-based power supply, and without having to start one of the main engines. An unusual design feature is that the APU is mounted in a hole in the keel beam web, in the main landing gear bay.[17] The 727 is equipped with a retractable tailskid that is designed to protect the aircraft in the event of an over-rotation on takeoff. The 727's fuselage has an outer diameter of 148 inches (3.8 m). This allows six-abreast seating (three per side) and a single aisle when 18-inch (46 cm) wide coach-class seats are installed. An unusual feature of the fuselage is the 10-inch (25 cm) difference between the lower lobe forward and aft of the wing as the higher fuselage height of the center section was simply retained towards the rear.

Nosewheel brakes were available as an option to reduce braking distance on landing, which provided reduction in braking distances of up to 150 m (490 ft).[19]

The 727 proved to be such a reliable and versatile airliner that it came to form the core of many startup airlines' fleets. The 727 was successful with airlines worldwide partly because it could use smaller runways while still flying medium-range routes. This allowed airlines to carry passengers from cities with large populations, but smaller airports to worldwide tourist destinations. One of the features that gave the 727 its ability to land on shorter runways was its clean wing design.[13] With no wing-mounted engines, leading-edge devices (Krueger, or hinged, flaps on the inner wing and extendable leading edge slats out to the wingtip) and trailing-edge lift enhancement equipment (triple-slotted,[20] fowler flaps) could be used on the entire wing. Together, these high-lift devices produced a maximum wing lift coefficient of 3.0 (based on the flap-retracted wing area).[17] The 727 was stable at very low speeds compared to other early jets, but some domestic carriers learned after review of various accidents that the 40-degree flap setting could result in a higher-than-desired sink rate or a stall on final approach. These carriers' Pilots' Operation Handbooks disallowed using more than 30° of flaps on the 727, even going so far as installing plates on the flap lever slot to prevent selection of more than 30° of flaps.

Noise

JT8D-1 through -17 engines

The 727 is one of the noisiest commercial jetliners, categorized as Stage 2 by the U.S. Noise Control Act of 1972, which mandated the gradual introduction of quieter Stage 3 aircraft. The 727's JT8D jet engines use older low-bypass turbofan technology, whereas Stage 3 aircraft use the more efficient and quieter high-bypass turbofan design. When the Stage 3 requirement was being proposed, Boeing engineers analyzed the possibility of incorporating quieter engines on the 727. They determined that the JT8D-200 engine could be used on the two side-mounted pylons. The JT8D-200 engines are much quieter than the original JT8D-1 through -17 variant engines that power the 727, as well as more fuel efficient due to the higher bypass ratio, but the structural changes to fit the larger-diameter engine (49.2 inches (125 cm) fan diameter in the JT8D-200 compared to 39.9 inches (101 cm) in the JT8D-1 through -17) into the fuselage at the number two engine location were prohibitive.

Current regulations require that a 727, or any other Stage 2 noise jetliner in commercial service must be retrofitted with a hush kit to reduce engine noise to Stage 3 levels to continue to fly in U.S airspace. These regulations have been in effect since December 31, 1999. One such hush kit is offered by FedEx,[21] and has been purchased by over 60 customers.[22] Aftermarket winglet kits, originally developed by Valsan Partners and later marketed by Quiet Wing Corp. have been installed on many 727s to reduce noise at lower speeds, as well as to reduce fuel consumption.[23] In addition, Raisbeck Engineering developed packages to enable 727s to meet the Stage 3 noise requirements. These packages managed to get light- and medium-weight 727s to meet Stage 3 with simple changes to the flap and slat schedules. For heavier-weight 727s, exhaust mixers must be added to meet Stage 3.[23] American Airlines ordered and took delivery of 52 Raisbeck 727 Stage 3 systems. Other customers included TWA, Pan Am, Air Algérie, TAME, and many smaller airlines.[24][25]

Since September 1, 2010, 727 jetliners (including those with a hush kit) are banned from some Australian airports because they are too loud.[26]

Operational history

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

In addition to domestic flights of medium range, the 727 was popular with international passenger airlines.[14] The range of flights it could cover (and the additional safety added by the third engine) meant that the 727 proved efficient for short- to medium-range international flights in areas around the world. Prior to its introduction, four-engined jets or propeller-driven airliners were required for transoceanic service.

The 727 also proved popular with cargo and charter airlines. FedEx Express introduced 727s in 1978.[27] The 727s were the backbone of its fleet until the 2000s; FedEx began replacing them with Boeing 757s in 2007.[27] Many cargo airlines worldwide employ the 727 as a workhorse, since, as it is being phased out of U.S. domestic service because of noise regulations, it becomes available to overseas users in areas where such noise regulations have not yet been instituted. Charter airlines Sun Country, Champion Air, and Ryan International Airlines all started with 727 aircraft.

The 727 had some military uses, as well. Since the aft stair could be opened in flight, the Central Intelligence Agency used them to drop agents and supplies behind enemy lines in Vietnam.[28]

The 727 has proven to be popular where the airline serves airports with gravel, or otherwise lightly improved, runways. The Canadian airline First Air, for example, previously used a 727-100C to serve the communities of Resolute Bay and Arctic Bay in Nunavut, whose Resolute Bay Airport and former Nanisivik Airport both have gravel runways. The high-mounted engines greatly reduce the risk of foreign object damage.

A military version, the Boeing C-22, was operated as a medium-range transport aircraft by the Air National Guard and National Guard Bureau to airlift personnel. A total of three C-22Bs were in use, all assigned to the 201st Airlift Squadron, District of Columbia Air National Guard.[29]

At the start of the 21st century, the 727 remained in service with a few large airlines. Faced with higher fuel costs, lower passenger volumes due to the post-9/11 economic climate, increasing restrictions on airport noise, and the extra expenses of maintaining older planes and paying flight engineers' salaries, most major airlines phased out their 727s; they were replaced by twin-engined aircraft, which are quieter and more fuel-efficient. Modern airliners also have a smaller flight deck crew of two pilots, while the 727 required two pilots and a flight engineer. Delta Air Lines, the last major U.S. carrier to do so, retired its last 727 from scheduled service in April 2003. Northwest Airlines retired its last 727 from charter service in June 2003. Many airlines replaced their 727s with either the 737-800 or the Airbus A320; both are close in size to the 727-200. As of July 2013, a total of 109 Boeing 727s (5× 727-100s and 104× -200s) were in commercial service with 34 airlines;[30] three years later, the total had fallen to 64 airframes (4× 727-100s and 60× -200s) with 26 airlines.[31]

On March 2, 2016, the first 727 produced (N7001U), which first flew on February 9, 1963, made a flight to a museum after extensive restoration. The 727-100 had carried about three million passengers during its years of service. Originally a prototype, it was later sold to United Airlines, which donated it to the Museum of Flight in Seattle in 1991. The jet was restored over 25 years by the museum and was ferried from Paine Field in Everett, Washington to Boeing Field in Seattle, where it was put on permanent display at the Aviation Pavilion.[32][33][34] The Federal Aviation Administration granted the museum a special permit for the 15-minute flight. The museum's previous 727-223, tail number N874AA, was donated to the National Airline History Museum in Kansas City and will be flown to its new home once FAA ferry approval is granted.[35]

On January 13, 2019, the last commercial passenger flight of a Boeing 727 was flown between Zahedan and Tehran by Iran Aseman Airlines.[2]

Variants

Data from: Boeing Aircraft since 1916[36]

The two series of 727 are the initial -100 (originally only two figures as in -30), which was launched in 1960 and entered service in February 1964, and the -200 series, which was launched in 1965 and entered service in December 1967.

727-100

%252C_USA_-_Air_Force_AN1131866.jpg.webp)

The first 727-100 (N7001U) flew on February 9, 1963.[32] FAA type approval was awarded on December 24 of that year, with initial delivery to United Airlines on October 29, 1963, to allow pilot training to commence. The first 727 passenger service was flown by Eastern Air Lines on February 1, 1964, between Miami, Washington, DC, and Philadelphia.

A total of 571 Boeing 727-00/100 series aircraft were delivered (407 -100s, 53 -100Cs, and 111 -100QCs), the last in October 1972. One 727-100 was retained by Boeing, bringing total production to 572.[37]

The -100 designation was assigned retroactively to distinguish the original short-body version. Actual aircraft followed a "727-00" pattern. Aircraft were delivered for United Airlines as 727-22, for American Airlines as 727-23, and so on (not -122, -123, etc.) and these designations were retained even after the advent of the 727-200.

- 727-100C

Convertible passenger cargo version, additional freight door and strengthened floor and floor beams, three alternative fits:

- 94 mixed-class passengers

- 52 mixed-class passengers and four cargo pallets (22,700 pounds; 10,300 kg)

- Eight cargo pallets (38,000 pounds; 17,000 kg)

- 727-100QC

QC stands for Quick Change. This is similar to the convertible version with a roller-bearing floor for palletised galley and seating and/or cargo to allow much faster changeover time (30 minutes).

%252C_United_Parcel_Service_(UPS)_JP5926976.jpg.webp)

- 727-100QF

QF stands for Quiet Freighter. A cargo conversion for United Parcel Service, these were re-engined with Stage 3-compliant Rolls-Royce Tay turbofans.

- Boeing C-22A

- A single 727-30 acquired from the Federal Aviation Administration, this aircraft was originally delivered to Lufthansa. It served mostly with United States Southern Command flying from Panama City / Howard Air Force Base.

- Boeing C-22B

- Four 727-35 aircraft were acquired from National Airlines by the United States Air Force for transporting Air National Guard and National Guard personnel.

727-200

A stretched version of the 727-100, the -200 is 20 feet (6.1 m) longer (153 feet 2 inches;46.69 m) than the -100 (133 feet 2 inches;40.59 m). A 10-ft (3-m) fuselage section ("plug") was added in front of the wings and another 10-ft fuselage section was added behind them. The wing span and height remain the same on both the -100 and -200 (108 and 34 feet (33 and 10 m), respectively). The original 727-200 had the same maximum gross weight as the 727-100; however, as the aircraft evolved, a series of higher gross weights and more powerful engines were introduced along with other improvements, and from line number 881, 727-200s are dubbed -200 Advanced. The aircraft gross weight eventually increased from 169,000 to 209,500 pounds (76,700 to 95,000 kg) for the latest versions. The dorsal intake of the number-two engine was also redesigned to be round in shape, rather than oval as it was on the -100 series.

The first 727-200 flew on July 27, 1967, and received FAA certification on November 30, 1967. The first delivery was made on December 14, 1967, to Northeast Airlines. A total of 310 727-200s were delivered before the -200 was replaced on the production line by the 727-200 Advanced in 1972.

- 727-200C

A convertible passenger cargo version, only one was built.

- 727-200 Advanced

The Advanced version of the 727-200 was introduced in 1970.[38] More powerful engines, fuel capacity and MTOW (185,800–210,000 lb or 84.3–95.3 t) increased the range from 1,930 to 2,550 nmi (3,570 to 4,720 km) or by 32%.[39] After the first delivery in mid-1972, Boeing eventually raised production to more than a hundred per year to meet demand by the late 1970s. Of the passenger model of the 727-200 Advanced, a total of 935 were delivered, after which it had to give way to a new generation of aircraft.

.jpg.webp)

- 727-200F Advanced

A freighter version of the 727-200 Advanced became available in 1981, designated the Series 200F Advanced. Powered by Pratt & Whitney JT8D-17A engines, it featured a strengthened fuselage structure, an 11 ft 2 in (3.40 m) by 7 ft 2 in (2.18 m) forward main deck freight door, and a windowless cabin. Fifteen of these aircraft were built, all for Federal Express. This was the last production variant of the 727 to be developed by Boeing; the last 727 aircraft completed by Boeing was a 727-200F Advanced.

.jpg.webp)

- Super 27

Certificated by Valsan Partners in December 1988 and marketed by Goodrich from 1997, the side engines are replaced by more efficient, quieter JT8D-217C/219, and the center engine gain an hush kit for $8.6 million (2000): fuel consumption is reduced by 10-12%, range and restricted airfield performance are improved.[40] Later marketed by Quiet Wing Technologies in Redmond, Washington, speed was increased by 50 mph (80 km/h), and Winglets were added to some of these aircraft to increase fuel efficiency.

- Boeing C-22C

- A single 727-212 aircraft was operated by the USAF.

Proposed

- 727-300

A proposed 169 seat version was developed in consultation with United Airlines in 1972, which initially expressed an interest in ordering 50 aircraft. There was also interest from Indian Airlines for a one-class version with 180 seats. The fuselage would have been lengthened by 18 feet (5.5 m) and the undercarriage strengthened. The three engines would have been replaced by two more powerful JT8D-217 engines under the T tail.[41][42] Many cockpit components would have been common with 737-200 and improved engine management systems would have eliminated the need for the flight engineer. United did not proceed with its order and Indian Airlines instead ordered the larger Airbus A300, so the project was cancelled in 1976.[43]

- 727-400

A concept with a 155 feet (47 m) fuselage and two high bypass turbofan engines under the wings (but retaining the T tail) was proposed in 1977. More compact systems, a redesign of the internal space and removing the need for the flight engineer would have increased the capacity to 189 seats in two class configuration. After only a few months the concept was developed into the Boeing 7N7 design which eventually became the Boeing 757.[44]

Operators

Commercial operators

.jpg.webp)

As of May 2020, there were 13 Boeing 727s (1× 727-100s and 12× -200s) in commercial service with 6 airlines, plus one in government and private use. Iran Aseman Airlines, the last passenger airline operator, made the last scheduled 727 passenger flight on 13 January 2019.[45] These operators have five or more aircraft for cargo as of July 2018:[46]

- Kalitta Charters (6)

- LAS Cargo (6)

- Serve Air (5)

T2 Aviation Ltd uses 2 modified former FedEx 727-200 freighters, operated by 2 Excel Aviation, equipped with oil dispersal tanks and spray booms to respond to oil spills.[47]

Zero Gravity Corporation uses a modified 727-200 in reduced-gravity passenger carrying operations.[48]

Colombian cargo carrier Aerosucre uses two 727-200s, registered HK-5216 and HK-5239, in addition to Total Linhas Aéreas, who also uses 3 727-200Fs.

Government, military, and other operators

.jpg.webp)

In addition, the 727 has seen sporadic government use, having flown for the Belgian, Yugoslav, Mexican, New Zealand, and Panama air forces, among the small group of government agencies that have used it.

- Afghan Air Force – Three being acquired from Ariana Afghan Airlines[49]

- Bolivian Air Force (Transporte Aereo Militar) (1)

- Burkina Faso Air Force (1)

- Colombian government

- Colombian Air Force (2)

- Force Aérienne du Congo (4)

- Iraqi government, Salah Aldin (1)

- Mexican Air Force (5) retired in 2017

- Federal Preventive Police (4)

- Royal New Zealand Air Force (3) retired in 2003

- United States Air Force – formerly used as a military transport, designated the C-22.

Private aircraft

A number of 727s have been outfitted for use as private aircraft, especially since the early 1990s when major airlines began to eliminate older 727-100 models from their fleet.[51] Donald Trump traveled in a former American Airlines 727-100 with dining room, bedroom and shower facilities known as Trump Force One before upgrading to a larger Boeing 757 in 2009;[52] Peter Nygård acquired a 727-100 for private use in 2005.[53] American Financier Jeffrey Epstein owned a private 727 nicknamed the "Lolita Express".[54] The Gettys bought N311AG from Revlon in 1986, and Gordon Getty acquired the aircraft in 2001.[55]

Accidents and incidents

As of January 2019, a total of 351 incidents involving 727s had occurred, including 119 hull-loss accidents[56] resulting in a total of 4,211 fatalities.[57]

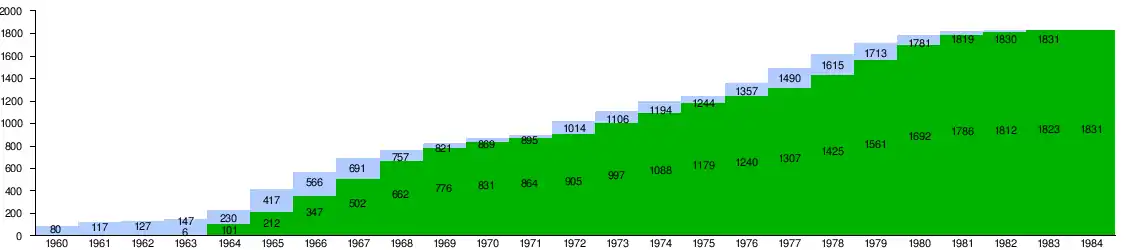

Orders and deliveries

| Year | Total | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | 1979 | 1978 | 1977 | 1976 | 1975 | 1974 | 1973 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orders | 1,831 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 38 | 68 | 98 | 125 | 133 | 113 | 50 | 88 | 92 |

| Deliveries | 1,831 | 8 | 11 | 26 | 94 | 131 | 136 | 118 | 67 | 61 | 91 | 91 | 92 |

| Year | 1972 | 1971 | 1970 | 1969 | 1968 | 1967 | 1966 | 1965 | 1964 | 1963 | 1962 | 1961 | 1960 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orders | 119 | 26 | 48 | 64 | 66 | 125 | 149 | 187 | 83 | 20 | 10 | 37 | 80 |

| Deliveries | 41 | 33 | 55 | 114 | 160 | 155 | 135 | 111 | 95 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

Source: Data from Boeing, through the end of production[58]

Boeing 727 orders and deliveries (cumulative, by year):

Orders

Deliveries

Model summary

| Model Series | ICAO code[59] | Orders | Deliveries |

|---|---|---|---|

| 727-100 | B721/R721[lower-alpha 2] | 407 | 407 |

| 727-100C | B721 | 164 | 164 |

| 727-200 | B722 | 1245 | 1245 |

| 727-200F | B722/R722[lower-alpha 2] | 15 | 15 |

| Total | 1831 | 1831 | |

Source: Boeing[58]

Aircraft on display

There are a comparatively large number of surviving retired 727s, largely as a result of donation by FedEx of 84 of them to various institutions. The vast majority of the aircraft were given to university aviation maintenance programs. All but 5 are located within the United States.[60]

- N7001U – 727-022 on static display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. It was the first 727 completed. It departed from Paine Field in Everett, Washington and landed at the museum on March 2, 2016.[61][62]

- N7017U – 727 on static display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois. It was donated by United Airlines. It features cut away sections showing airplane framework and lavatory, cockpit view, and a few rows of seating.[63][64]

- N186FE – 727-100 on static display at Owens Community College in Perrysburg, Ohio. It formerly operated by FedEx and donated by the company in 2007.[65][66]

- N199FE – 727-173C on static display at the Kansas Aviation Museum in Wichita, Kansas. It was formerly operated by FedEx as N199FE.[67][68]

- N113FE Jarrod – 727-022C in storage at the National Museum of Commercial Aviation in Atlanta, Georgia. It was formerly operated by FedEx as N113FE, and by United Airlines before that as N7437U.[69]

- N265SE Paul – 727-200 on static display at the Florida Air Museum in Lakeland, Florida. It was formerly operated by FedEx.[70][71]

- N492FE Two Bears – 727-227 on static display with the University of Alaska at Merrill Field in Anchorage, Alaska. It was formerly operated by FedEx and was donated by the company on February 26, 2013.[72][73][74][75]

- N874AA – 727-223 stored for the Airline History Museum at Boeing Field in Seattle, Washington.[76]

- NZ7272 - 727-22C nose is currently stored at the Air Force Museum of New Zealand in Christchurch, New Zealand and is yet to go on display.

- G-BNNI Lady Patricia – 727-276 last flown by Sabre Airways in 2000. Purchased by 727 Communications, an advertising company in Skanderborg, Denmark, it now serves as a conference room and billboard at their offices.[77][78]

Specifications

| Variant | 727-100 | 727-200 |

|---|---|---|

| Flight crew[80] | three: pilot, copilot, and flight engineer | |

| Two-class seats | 106: 16F@38", 90Y@34" | 134: 20F@38", 114Y@34" |

| One-class seats | 125@34" | 155@34" |

| Exit limit[80] | 131 | 189 |

| Length | 133ft2in / 40.59m | 153ft2in / 46.68m |

| Height | 34ft3in / 10.44m | 34ft11in / 10.65m |

| Cabin width | 140in / 3.56m | |

| Wingspan | 108 ft / 32.92m | |

| Wing[39] | 1,650 sq ft (153 m2), 32° sweep | |

| MTOW | 169,000 lb / 76,700 kg | 172,000 lb / 78,100 kg Adv. 209,500 lb / 95,100 kg |

| OEW | 87,696 lb / 39,800 kg | 97,650 lb / 44,330 kg Adv. 100,700 lb / 45,720 kg |

| Fuel capacity | 7,680gal / 29,069L | 8,090USgal / 30,620L Adv. 10,585USgal / 40,060L |

| Engines ×3 | Pratt & Whitney JT8D-1/7/9 | JT8D-7/9/11 (Adv.: -9/15/17/17R) |

| Thrust ×3 | 14,000–14,500 lbf (62–64 kN) | 14,000–15,000 lbf (62–67 kN) Adv. 14,500–17,400 lbf (64–77 kN) |

| Range[lower-alpha 3] | 2,250 nmi (4,170 km) | 1,900 nmi (3,500 km) Adv. 2,550 nmi (4,720 km) |

| Take-off[lower-alpha 4] | 8,300 ft (2,500 m) | 8,400 ft (2,600 m) Adv. 10,100 ft (3,100 m) |

| MMO[80] | Mach 0.9 (961 km/h; 519 kn) | |

| Cruise | 495 kn/ 917 km/h / Mach 0.86[81] | 865–953 km/h / 467-515kt [82] |

| Ceiling[80] | 42,000 ft (13,000 m) | |

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

Notes

- Retired from airline passenger use in January 2019[2]

- R721/R722 refers to Super 27 variants.

- Two-class passengers

- MTOW, SL, ISA

References

- "727 Commerciat transport : Historical Snapshot". Boeing.

- Guy, Jack (January 22, 2019). "Boeing's famous trijet 727 makes last commercial flight". CNN.

- "727 Family". Boeing Commercial Airplanes. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

By January 1983, orders reached 1,831. One Boeing-owned test airplane brought the grand total to 1,832.

- "Commercial Jets". Modern Marvels. Season A149. January 16, 2001. approx. 15 minutes in.

- Connors 2010, p. 355

- Technical Editor (December 16, 1960). "Analysing the 727". Flight. Vol. 78 no. 2071. Retrieved April 1, 2015 – via Flightglobal Archive.

- Alastair Pugh (December 30, 1960). "Boeing's Trimotor". Flight. Vol. 78 no. 2073. Retrieved April 1, 2015 – via Flightglobal Archive.

- Connors 2010, p. 357

- "Talking to Mr Beall: Boeing's Senior Vice-President in London". Flight. Reed Business Information. October 4, 1960. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- Connors 2010, pp. 348–349

- Connors 2010, p. 350

- Connors 2010, p. 352

- Eden, Paul. (Ed). Civil Aircraft Today. 2008: Amber Books, pp. 72–3.

- Eden 2008, pp. 74–5.

- Norris and Wagner. Modern Boeing Jetliners, pp. 12–3. Motorbooks International, 1999.

- "Boeing 727 series. Aircraft & Powerplant Corner."

- Case Study in Aircraft Design; the Boeing 727, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Professional Study Series, September 1978.

- Bruce Schneier (2003). Beyond Fear: Thinking Sensibly about Security in an Uncertain World. p. 82. ISBN 0-387-02620-7.

- Lufthansa. Operating Manual Boeing 727, pp. 1.4.32-1, 4.3.4-2.

- "Boeing 727". Boeing. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- "Boeing 727 - Stage 3 Kits". fedex.com. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- "Case Study - Plane Quiet". fedex.com. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- "Hushkit Survey" (PDF). Flight International. Vol. 159 no. 4789. July 13, 2001. p. 41.

- James Raisbeck. "Breathing New Technology into Aviation". Archived from the original on June 27, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- "Boeing 727 Stage 3 Noise Reduction Kits". Archived from the original on June 3, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Creedy, Steve (March 30, 2010). "Noisy Boeing 727s will be banned". News Corporation. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- "End of an Era as FedEx Express Retires Last B727". FedEx.com. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Himmelsbach & Worcester 1986, p. 43.

- Frawley, Gerard (2002). The International Directory of Military Aircraft, 2002–2003. Fyshwick, ACT, Australia: Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd. ISBN 1-875671-55-2.

- "World Airliner Census". Flight International. Vol. 184 no. 5403. August 13, 2013. pp. 40–58 [49].

- FlightGlobal (2017). World Airliner Census (PDF). p. 34. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- Farris, Brandon; King, Royal Scott. "Iconic first Boeing 727 makes final flight". CNN. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- Siebenmark, Jerry (March 2, 2016). "Final Flight of First 727 Planned for Wednesday". Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- Siebenmark, Jerry (March 3, 2016). "Wichitans made parts for, flew on Boeing 727". Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- "Boeing 727-223". National Airline History Museum. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- Bowers, Peter M. (June 1989). Boeing Aircraft since 1916. USA: Naval Institute Press. pp. 481–492. ISBN 978-3-8228-9663-1.

- Airclaims Jet Programs 1995

- Gilchrist, p.62

- "727-100/200" (PDF). Startup. Boeing. 2007.

- "Hushkit Survey" (PDF). Flight International. Vol. 159 no. 4789. July 13, 2001. p. 42.

- "American Aviation Historical Society Journal". American Aviation Historical Society. 1999: 121. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Mark Wagner (1998). Boeing Jetliners. Barnes & Noble. p. 67. ISBN 1610607066.

- "Asia Defense Journal". Vikrant Group. 1977. p. 22.

- "Shortlines". Aviation Week & Space Technology. 107: 4. 1977.

- Falcus, Matt (January 14, 2019). "Iran Aseman Retires Last Scheduled Boeing 727". Airport Spotting Blog. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- "World Airline Census 2018". Flightglobal.com. July 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- "Lines of Business: T2". 2Excel Aviation. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- "Zero Gravity Corporation: The Experience". Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- "Afghan AF acquires 3 Boeing 727s". Air Forces Monthly. Key Publishing: 30. December 2014.

- "Djibouti Air Force gets two Y-12s; Dauphin helicopters". defenceWeb. 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- "REBUILDING SECOND-HAND 727'S". The New York Times. November 7, 1981. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- "Inside Donald Trump's private jet - The exterior (1) - CNNMoney.com". money.cnn.com. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- "NYGARD Corporate site". corporate.nygard.com. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- Ostler, Catherine. "Jeffrey Epstein: The Sex Offender Who Mixes With Princes and Premiers". Newsweek. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- https://www.jetphotos.com/info/727-20512

- "Boeing 727 Accident summary", Aviation-Safety.net, May 5, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Boeing 727 Accident Statistics", Aviation-Safety.net, December 3, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "727 Model Summary". Boeing Commercial Airplanes. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- "ICAO Document 8643". International Civil Aviation Organization. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- Bostick, Brian (November 24, 2014). "Interactive Map: Retired FedEx Boeing 727s Dot The Globe". Aviation Week Network. Penton. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- "Boeing 727-022". The Museum of Flight. The Museum of Flight. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Farris, Brandon (March 3, 2016). "The First Boeing 727 Prepares For a Last Flight". Airways News. Airways International, Inc. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- "United Airlines Boeing 727." Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. Retrieved: 19 December 2016.

- "Airframe Dossier - Boeing 727-22, c/n 18309, c/r N7017U". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- "FedEx Donates Boeing 727 Aircraft to Owens Community College". Owens Community College. Owens Community College. April 19, 2007. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- "Airframe Dossier - Boeing B727 / C-22, c/n 18872, c/r N186FE". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- "Boeing 727". Kansas Aviation Museum. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- "Airframe Dossier - Boeing 727-173C, c/n 19509, c/r N199FE". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- "FEDEX 727-022C; S/N 19894". National Museum of Commercial Aviation. National Museum of Commercial Aviation. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- "EXHIBITS". Sun 'n Fun. SUN 'n FUN. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- "N265FE Federal Express (FedEx) Boeing 727-200 - cn 21671 / 1523". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Mondor, Colleen (May 31, 2016). "Small Alaska airport makes room for FedEx 727". adn.com. Alaska Dispatch Publishing. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- "UAA welcomes donated Boeing 727 jet from FedEx". Green & Gold News. February 25, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- Erickson, Evan (March 12, 2013). "The Eagle Has Landed At Merrill Field: FedEx Donates Boeing 727 To Aviation Program". The Northern Light. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- "N492FE Federal Express (FedEx) Boeing 727-200 - cn 21530 / 1446". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- "BOEING 727-223". Airline History Museum. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- "VH-TBK Boeing 727-276A". www.aussieairliners.org. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- "G-BNNI | Boeing 727-276(Adv) | 727 Communication | Soren Madsen | JetPhotos". JetPhotos. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- "727 Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning" (PDF). Boeing. May 2011.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet" (PDF). FAA. February 20, 1991. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- Gerard Frawley. "727-100 aircraft technical data & specifications". The International Directory of Civil Aircraft.

- Gerard Frawley. "727-200 aircraft technical data & specifications". The International Directory of Civil Aircraft.

- Connors, Jack (2010). The Engines of Pratt & Whitney: A Technical History. Reston. Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. ISBN 978-1-60086-711-8.

- Himmelsbach, Ralph P.; Worcester, Thomas K. (1986). Norjak: The Investigation of D. B. Cooper. West Linn, Oregon: Norjak Project. ISBN 978-0-9617415-0-1.

- Gilchrist, Peter (1996). Modern Civil Aircraft 13: Boeing 727. Shepperton, United Kingdom: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 0-7110-2081-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- "727 Commerciat transport : Historical Snapshot". Boeing.

- 727 prototype on rbogash.com

- Boeing-727.com site

- Fatal Boeing 727 Events on Airsafe.com

- "Boeing jet has new appearance". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). (AP photo). November 2, 1962. p. 2B.

- Murdo Morrison (November 28, 2014). "Soldiering on: 10 veteran airliner types still in service". Flightglobal.

- Guy Norris (January 16, 2015). "727 And The Birth Of Boeing's 'Family' Plan (1962)". Aviation Week. From The Archives.

|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}|style="width:calc(100% / 67);"|{{#invoke:String|pos|{{{1}}}|4}}