Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault

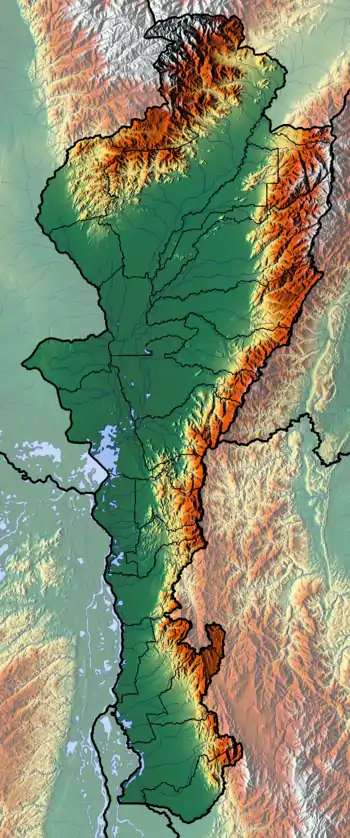

The Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault (BSMF, BSF) or Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault System (Spanish: (Sistema de) Falla(s) de Bucaramanga-Santa Marta) is a major oblique transpressional sinistral strike-slip fault (wrench fault) in the departments of Magdalena, Cesar, Norte de Santander and Santander in northern Colombia. The fault system is composed of two main outcropping segments, named Santa Marta and Bucaramanga Faults, and an intermediate Algarrobo Fault segment in the subsurface. The system has a total length of 674 kilometres (419 mi) and runs along an average north-northwest to south-southeast strike of 341 ± 23 from the Caribbean coast west of Santa Marta to the northern area of the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes.

| Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault | |

|---|---|

| Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault System (Sistema de) Falla(s) de Bucaramanga-Santa Marta | |

View of the Bucaramanga Fault along Bucaramanga | |

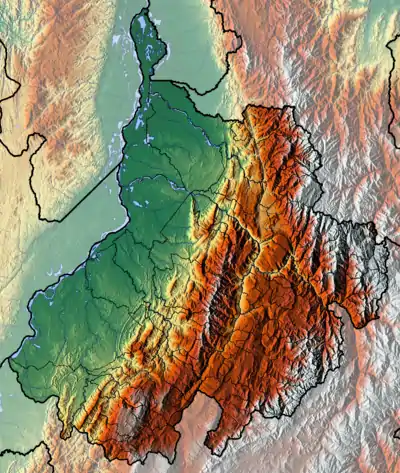

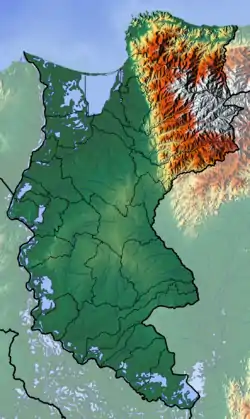

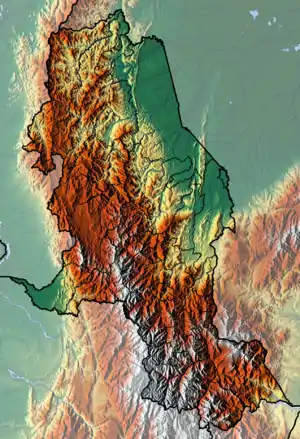

Location of the fault in Colombia  Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault (Santander Department) | |

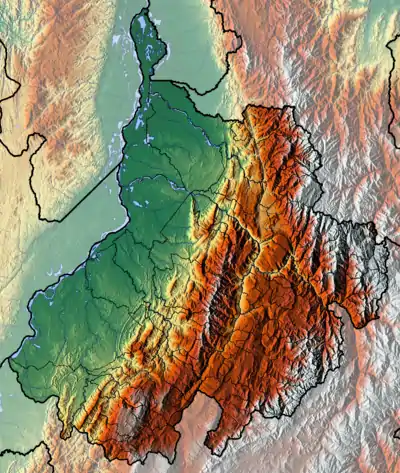

Topographic map of northern Colombia showing the fault | |

| Etymology | Bucaramanga, Santa Marta |

| Coordinates | 7°05′25″N 73°05′15″W |

| Country | Colombia |

| Region | Caribbean, Andean |

| State | Magdalena, Cesar, Norte de Santander, Santander |

| Cities | Santa Marta, El Paso, Bucaramanga, Floridablanca, Piedecuesta |

| Characteristics | |

| Elevation | 1–1,500 m (3.3–4,921.3 ft) |

| Range | Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta Eastern Ranges Andes |

| Part of | Andean faults |

| Segments | Santa Marta, Algarrobo, Bucaramanga Faults |

| Length | 674 km (419 mi) |

| Strike | 341 ± 23 (NNW-SSE) |

| Displacement | 110 km (68 mi) |

| Tectonics | |

| Plate | South American Plate |

| Status | Active |

| Earthquakes | Pre-Columbian era (~1020 AD) |

| Type | Strike-slip fault |

| Movement | Sinistral |

| Rock units | Caribbean, La Guajira, Tahamí & Chibcha Terranes |

| Age | Neogene-Holocene |

| Orogeny | Andean |

The fault system is a major bounding fault for various sedimentary basins and igneous and metamorphic complexes. The northern Santa Marta Fault segment separates the Sinú-San Jacinto Basin and Lower Magdalena Valley in the west from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta to the east. The buried Algarrobo Fault segment forms the boundary between the Lower Magdalena Valley and northern Middle Magdalena Valley to the west and the Cesar-Ranchería Basin in the east. The Bucaramanga Fault segment separates the middle part of the Middle Magdalena Valley in the west from the Santander Massif in the east.

The fault system bounds and cuts the four largest terranes of the North Andes Plate; the La Guajira, Caribbean and Tahamí Terranes along the Santa Marta section and intraterrane movement in the Andean Chibcha Terrane. Studies of the fault segments have shown the fault was active in the pre-Columbian era, around the year 1020, when the area around Bucaramanga was inhabited by the Guane. Various seismic events analysed to have occurred during the Holocene of the Bucaramanga Fault segment lead to the conclusion the fault is active.

Description

The Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault is a major fault system which extends for a total distance of 674 kilometres (419 mi) from the Colombian Caribbean coast to the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes to as far as about 6.5° N, south of the capital of Santander, Bucaramanga. The fault system, with an average strike of 341 ± 23 degrees, is a major wrench fault with a sinistral (left-lateral) displacement ranging from 45 to 110 kilometres (28 to 68 mi) and a fault slip rate of 0.01 to 0.2 millimetres (0.00039 to 0.00787 in) per year.[1] The Santa Marta Fault forms the boundary between several distinct geological provinces: it is the western limit of the Santa Marta Massif with the Sinú-San Jacinto Basin, farther to the south the fault separates the Lower Magdalena Valley and northern Middle Magdalena Valley from the Cesar-Ranchería Basin. The Santander Massif is separated from the central part of the Middle Magdalena Valley along the southern Bucaramanga Fault segment of the fault system.[2]

The fault divides the northern part of the Eastern Ranges in two structurally distinct regions. The Andean uplifted eastern block mainly comprises crystalline igneous and metamorphic rocks of Paleozoic and pre-Cambrian age, with lesser amounts of Jurassic, Triassic and Tertiary sedimentary rocks. In the western downthrown block, predominately sedimentary rocks of Quaternary and Tertiary age are found, with lesser amounts of Cretaceous and Jurassic rocks. The northern half of the fault is partially covered by Quaternary deposits in the Cesar and Magdalena valleys.[2]

Segments

The fault is divided into three segments; the main Bucaramanga Fault segment in the south, the Algarrobo Fault in the central section,[3] and the main Santa Marta Fault segment in the northern part of the fault system.[4][5][6] Between the two main outcropping segments, the Algarrobo Fault is present in the subsurface, overlain by Quaternary sediments.[7][8][9][10][11] The urban centre of the major coal producing municipality El Paso, Cesar is located right above the fault.[9] The fault reappears at surface east of Tamalameque, Cesar, where it continues south-southeastward into the Eastern Ranges in the departments of Norte de Santander and Santander.[12][13][14][15][16][17] The fault can be traced until San Andrés, Santander.[18] The Bucaramanga Fault possibly continues as the compressional Boyacá and Soapaga Faults on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense.[19]

Municipalities

| Municipality bold is capital |

Department | Altitude of urban centre |

Inhabitants 2015 |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Marta | Magdalena | 0 m (0 ft) | 466,000 | |

| Ciénaga | Magdalena | 10 m (33 ft) | 104,897 | |

| Zona Bananera | Magdalena | 30 m (98 ft) | 60,524 | |

| Aracataca | Magdalena | 40 m (130 ft) | 39,473 | |

| Fundación | Magdalena | 10 m (33 ft) | 57,344 | |

| Algarrobo | Magdalena | 24 m (79 ft) | 12,576 | |

| El Copey | Cesar | 180 m (590 ft) | 27,212 | |

| Bosconia | Cesar | 200 m (660 ft) | 37,248 | |

| El Paso | Cesar | 36 m (118 ft) | 22,832 | |

| Chiriguaná | Cesar | 40 m (130 ft) | 19,650 | |

| Curumaní | Cesar | 112 m (367 ft) | 24,367 | |

| Chimichagua | Cesar | 49 m (161 ft) | 30,658 | |

| Pailitas | Cesar | 77 m (253 ft) | 17,166 | |

| Pelaya | Cesar | 50 m (160 ft) | 17,910 | |

| La Gloria | Cesar | 50 m (160 ft) | 12,938 | |

| El Carmen | Norte de Santander | 761 m (2,497 ft) | 14,005 | |

| Teorama | Norte de Santander | 72 m (236 ft) | 21,524 | |

| González | Cesar | 1,240 m (4,070 ft) | 6990 | |

| Ocaña | Norte de Santander | 1,202 m (3,944 ft) | 98,992 | |

| San Martín | Cesar | 119 m (390 ft) | 18,548 | |

| San Alberto | Cesar | 125 m (410 ft) | 24,653 | |

| Ábrego | Norte de Santander | 1,398 m (4,587 ft) | 38,627 | |

| La Esperanza | Norte de Santander | 1,566 m (5,138 ft) | 12,012 | |

| Cáchira | Norte de Santander | 2,025 m (6,644 ft) | 10,970 | |

| El Playón | Santander | 469 m (1,539 ft) | 11,776 | |

| Rionegro | Santander | 590 m (1,940 ft) | 27,114 | |

| Bucaramanga | Santander | 959 m (3,146 ft) | 528,575 | |

| Floridablanca | Santander | 925 m (3,035 ft) | 266,669 | |

| Piedecuesta | Santander | 1,005 m (3,297 ft) | 156,167 | |

| Cepitá | Santander | 660 m (2,170 ft) | 1865 | |

| San Andrés | Santander | 1,777 m (5,830 ft) | 8540 | |

Tectonic setting

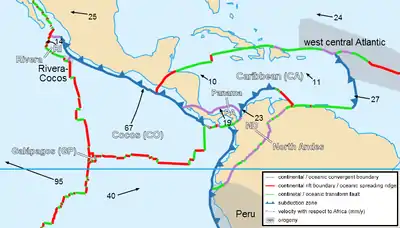

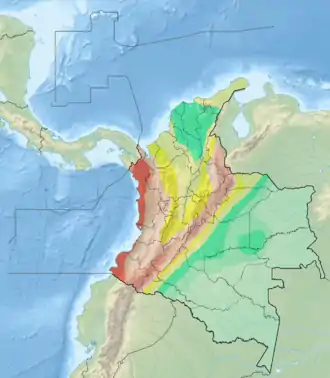

The Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault system is located in northwestern South America, on the North Andes Plate, where the 20 ± 2 millimetres (0.787 ± 0.079 in)/yr east to southeastward moving Caribbean,[52] 60 mm (2.4 in)/yr eastward subducting Malpelo,[53] and South American Plates converge. Since Early Mesozoic times, the western portion of Colombia was subjected to different episodes of subduction, accretion and collision, at the boundaries of the South America continental and the oceanic Farallon, Nazca, and Caribbean Plates and various island arcs.[54] The interaction of the plate tectonic movements formed the Northern Andean Block, separated from the Maracaibo Block by the Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault.[55] The Northern Andean Block is subdivided into tectonic realms, with the Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault separating the Central Continental Sub-plate Realm in the west from the Maracaibo Sub-plate Realm in the east.[56] It has been suggested that these two realms are dominated by respectively Nazca and Caribbean Plate subduction.[57] The compressional stress regime caused the formation of the oblique sinistral Bucaramanga-Santa Marta Fault and dextral Oca and Boconó Faults.[58]

The interplay between the Santa Marta and Oca Faults produced offshore Caribbean platforms and valleys north of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta near Taganga.[59] Uplift along the western margin of the Santa Marta Fault probably commenced in the Pliocene.[60]

The Bucaramanga Fault intersects with the Boconó Fault at the Santander Massif.[61] In this area, the top of the subducting slab has been estimated at an initial depth of approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi), then a horizontal part for about 50 kilometres (31 mi), and a farther descending section to reach a depth of around 200 kilometres (120 mi). The slab section, called Bucaramanga slab, here has a dip that continues to the oceanic crust of the Caribbean seafloor. Towards the north of the Bucaramanga Nest or Swarm, in a north-south area approximately 200 kilometres (120 mi) in length, a well-defined Wadati-Benioff Zone extending to 175 kilometres (109 mi) depth has been identified.[62]

Activity

A study published in 2009 about the Bucaramanga segment of the fault system revealed that the fault had eight episodes of activity during the late Holocene.[63] The most recent activity has been inferred to have been around the year 1020.[64] During this pre-Columbian era, the area around Bucaramanga was inhabited by the indigenous Guane. The authors consider the Bucaramanga Fault therefore as active.[63]

Other faults in the seismically active zone, named Bucaramanga Nest, produced 27 earthquakes of magnitudes 4.0 to 5.3 between May 2012 and January 2013.[65]

Panorama

Notes and references

Notes

- 2017 population data

- 2016 population data

References

- Jiménez Díaz, 2013, p.56

- Paris et al., 2000, p.10

- Cuéllar et al., 2012, p.77

- Plancha 11, 1998

- Plancha 18, 1999

- Plancha 19, 2007

- Plancha 26, 2007

- Plancha 33, 2007

- Plancha 40, 2002

- Plancha 47, 2001

- Plancha 55, 2006

- Plancha 65, 1994

- Plancha 66, 2009

- Plancha 76, 1980

- Plancha 86, 1981

- Plancha 97, 1981

- Plancha 120, 1977

- Plancha 136, 1984

- Sánchez et al., 2012, p.3008

- DANE, 2015, p.29

- (in Spanish) Official website Santa Marta

- (in Spanish) Official website Ciénaga

- (in Spanish) Official website Zona Bananera

- (in Spanish) Official website Aracataca

- (in Spanish) Official website Fundación

- (in Spanish) Official website Algarrobo

- (in Spanish) Official website El Copey

- (in Spanish) Official website Bosconia

- (in Spanish) Official website El Paso, Cesar

- (in Spanish) Official website Chiriguaná

- (in Spanish) Official website Curumaní

- (in Spanish) Official website Chimichagua

- (in Spanish) Official website Pailitas

- (in Spanish) Official website Pelaya

- (in Spanish) Official website La Gloria, Cesar

- (in Spanish) Official website El Carmen

- (in Spanish) Official website Teorama

- (in Spanish) Official website González, Cesar

- (in Spanish) Official website Ocaña

- (in Spanish) Official website San Martín, Cesar

- (in Spanish) Official website San Alberto, Cesar

- (in Spanish) Official website Ábrego

- (in Spanish) Official website La Esperanza

- (in Spanish) Official website Cáchira

- (in Spanish) Official website El Playón

- (in Spanish) Official website Rionegro

- (in Spanish) Official website Bucaramanga

- (in Spanish) Official website Floridablanca

- (in Spanish) Official website Piedecuesta

- (in Spanish) Official website Cepitá

- (in Spanish) Official website San Andrés

- Egbue et al., 2014, p.9

- Colmenares & Zoback, 2003, p.721

- Nevistic et al., 2003, p.132

- Colmenares & Zoback, 2003, p.722

- Cediel et al., 2003, p.818

- Yarce et al., 2014, p.57

- Idárraga García et al., 2011, p.44

- Posada Posada et al., 2012, p.103

- Idárraga García et al., 2011, p.57

- Diederix et al., 2009, p.19

- Colmenares & Zoback, 2003, p.723

- Diederix et al., 2009, p.23

- Diederix et al., 2009, p.21

- Perico & Perico, 2014, p.6

Bibliography

- Cediel, Fabio; Robert P. Shaw, and Carlos Cáceres. 2003. Tectonic Assembly of the Northern Andean Block - The Circum-Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean: Hydrocarbon habitats, basin formation, and plate tectonics. AAPG Memoir 79. 815–848.

- Colmenares, Lourdes, and Mark D. Zoback. 2003. Stress field and seismotectonics of northern South America. Geology 31. 721–724.

- Cuéllar Cárdenas, Mario Andrés; Julián Andrés López Isaza; Jairo Alonso Osorio Naranjo, and Edgar Joaquín Carrillo Lombana. 2012. Análisis estructural del segmento Bucaramanga del Sistema de Fallas de Bucaramanga (SFB) entre los municipios de Pailitas y Curumaní, Cesar - Colombia. Boletín de Geología, Universidad Industrial de Santander 34. 73–101. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Diederix, Hans; Catalina Hernández M.; Eliana Torres J.; Jairo Alonso Osorio, and Paola Botero. 2009. Resultados preliminares del primer estudio paleosismológico a lo largo de la Falla de Bucaramanga, Colombia. Ingeniería, Investigación y Desarrollo, UPTC 9. 18–23. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Egbue, Obi; James Kellogg; Hector Aguirre, and Carolina Torres. 2014. Evolution of the stress and strain fields in the Eastern Cordillera, Colombia. Journal of Structural Geology 58. 8–21.

- Idárraga García, Javier; Blanca Oliva Posada, and Georgina Guzmán. 2011. Geomorfología de la zona costera adyacente al piedemonte occidental de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta entre los sectores de Pozos Colorados y el Río Córdoba, Caribe Colombiano. Boletín de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras, INVEMAR 40. 41–58.

- Jiménez Díaz, Giovanny. 2013. Relationship between curved thrust belts, rift inversion, oblique convergence and strike-slip faulting - an example of Eastern Cordillera in Colombia (PhD thesis), 1–106. Università di Roma.

- Nevistic, A.V.; E.A. Rossello; C.E. Haring; G. Covellone; F. Bettini; H. Rodríguez; R. Salay; C. Colo, and L. Araque, E. Castro, C. Pinilla, C.P. Bordarampé. 2003. The Andean Santander-Oriental Tectonic Syntaxis: A first-order pattern controlling exploration play-model concepts in Colombia, 130–134. VIII Simposio Bolivariano - Exploración Petrolera en las Cuencas Subandinas.

- Paris, Gabriel; Michael N. Machette; Richard L. Dart, and Kathleen M. Haller. 2000. Map and Database of Quaternary Faults and Folds in Colombia and its Offshore Regions, 1–66. USGS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Perico Martínez, Néstor Rafael, and Néstor Rafael Perico Granados. 2014. Caracterización y recurrencia sísmica del Nido de Bucaramanga, 1–19. V Congreso Internacional de Ingeniería Civil, Universidad Santo Tomás Seccional Tunja.

- Posada Posada, Blanca Oliva; Carlos A. Andrade, and Yves-François Thomas. 2012. Estructura del subsuelo de la plataforma continental aledaña a las estribaciones de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, bahías de Taganga, Santa Marta y Gaira. Boletín Científico, CIOH 30. 93–104.

- Sánchez, Javier; Brian K. Horton; Eliseo Tesón; Andrés Mora; Richard A. Ketcham, and Daniel F. Stockli. 2012. Kinematic evolution of Andean fold-thrust structures along the boundary between the Eastern Cordillera and Middle Magdalena Valley basin, Colombia. Tectonics 31. 1–24. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Various, Authors. 2016. Informe de coyuntura económica regional - Departamento de Magdalena, 1–99. DANE. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Yarce, Jefferson; Gaspar Monsalve; Thorsten W. Becker; Agustín Cardona; Esteban Poveda; Daniel Alvira, and Oswaldo Ordoñez Carmona. 2014. Seismological observations in Northwestern South America: Evidence for two subduction segments, contrasting crustal thicknesses and upper mantle flow. Tectonophysics 637. 57–67.

Maps

- Hernández, Marina, and Jairo Clavijo. 1998. Plancha 11 - Santa Marta - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Hernández, Marina, and Iván Maldonado. 1999. Plancha 18 - Ciénaga - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Colmenares, Fabio; Milena Mesa; Jairo Roncancio; Edgar Arciniegas; Pablo Pedraza; Agustín Cardona; César Silva; Jhoamna Romero, and Sonia Alvarado and Oscar Romero, Felipe Vargas, Carlos Santamaría. 2007. Plancha 19 - Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Colmenares, Fabio; Milena Mesa; Jairo Roncancio; Edgar Arciniegas; Pablo Pedraza; Agustín Cardona; César Silva; Jhoamna Romero, and Sonia Alvarado and Oscar Romero, Felipe Vargas, Carlos Santamaría. 2007. Plancha 26 - Pueblobello - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Colmenares, Fabio; Milena Mesa; Jairo Roncancio; Edgar Arciniegas; Pablo Pedraza; Agustín Cardona; César Silva; Jhoamna Romero, and Sonia Alvarado and Oscar Romero, Felipe Vargas, Carlos Santamaría. 2007. Plancha 33 - El Copey - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- González, Javier; Jairo Clavijo; Marina Hernández, and Carlos García. 2002. Plancha 40 - Bosconia - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Hernández, Marina; Jairo Clavijo, and Javier González. 2001. Plancha 47 - Chiriguaná - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Bernal Vargas, Luis Enrique, and Luis Carlos Mantilla Figueroa. 2006. Plancha 55 - El Banco - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Royero, José María; Jairo Clavijo; Hernando Mendoza; Gonzalo Barbosa; G. Vargas; R.E. Bernal, and P. Ferreira. 1994. Plancha 65 - Tamalameque - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Daconte, Rommel; Rosalba Salinas; José María Royero; Jairo Clavijo; Alfonso Arias; Luz S. Carvajal; Martín E. López; Leonidas Angarita, and Hernando Mendoza. 2009. Plancha 66 - Miraflores - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Daconte, Rommel, and Rosalba Salinas. 1980. Plancha 76 - Ocaña - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Vargas, Rodrigo, and Alfonso Arias. 1981. Plancha 86 - Ábrego - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Vargas, Rodrigo, and Alfonso Arias. 1981. Plancha 97 - Cáchira - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Ward, Dwight E.; Richard Goldsmith; Andrés Jimeno; Jaime Cruz; Hernán Restrepo, and Eduardo Gómez. 1977. Plancha 120 - Bucaramanga - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.

- Vargas, Rodrigo; Alfonso Arias; Luis Jaramillo, and Noel Tellez. 1984. Plancha 136 - Málaga - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-20.