Hispania Baetica

Hispania Baetica, often abbreviated Baetica, was one of three Roman provinces in Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula). Baetica was bordered to the west by Lusitania, and to the northeast by Hispania Tarraconensis. Baetica remained one of the basic divisions of Hispania under the Visigoths down to 711. Baetica was part of Al-Andalus under the Moors in the 8th century and approximately corresponds to modern Andalusia.

| Provincia Hispania Baetica | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of the Roman Empire | |||||||

| 14 BC–5th century | |||||||

.svg.png.webp) The Roman province of Hispania Baetica, c. 125 AD | |||||||

| Capital | Corduba | ||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||||

• Established | 14 BC | ||||||

• Visigothic conquest | 5th century | ||||||

| |||||||

Name

In Latin, Baetica is an adjectival form of Baetis, the Roman name for the Guadalquivir River, whose fertile valley formed one of the most important parts of the province.

History

Before Romanization, the mountainous area that was to become Baetica was occupied by several settled Iberian tribal groups. Celtic influence was not as strong as it was in the Celtiberian north. According to the geographer Claudius Ptolemy, the indigenes were the powerful Turdetani, in the valley of the Guadalquivir in the west, bordering on Lusitania, and the partly Hellenized Turduli with their city Baelo, in the hinterland behind the coastal Phoenician trading colonies, whose Punic inhabitants Ptolemy termed the "Bastuli". Phoenician Gadira (Cadiz) was on an island against the coast of Hispania Baetica. Other important Iberians were the Bastetani, who occupied the Almería and mountainous Granada regions. Towards the southeast, Punic influence spread from the Carthaginian cities on the coast: New Carthage (Roman Cartago Nova, modern Cartagena), Abdera and Malaca (Málaga).

Some of the Iberian cities retained their pre-Indo-European names in Baetica throughout the Roman era. Granada was called Eliberri, Illiberis and Illiber by the Romans; in Basque, "iri-berri" or "ili-berri", still signifies "new town".

The south of the Iberian peninsula was agriculturally rich, providing for export of wine, olive oil and the fermented fish sauce called garum that were staples of the Mediterranean diet, and its products formed part of the western Mediterranean trade economy even before it submitted to Rome in 206 BC. After the defeat of Carthage in the Second Punic War, which found its casus belli on the coast of Baetica at Saguntum, Hispania was significantly Romanized in the course of the 2nd century BC, following the uprising initiated by the Turdetani in 197. The central and north-eastern Celtiberians soon followed suit. It took Cato the Elder, who became consul in 195 BC and was given the command of the whole peninsula to put down the rebellion in the northeast and the lower Ebro valley. He then marched southwards and put down a revolt by the Turdetani. Cato returned to Rome in 194, leaving two praetors in charge of the two Iberian provinces. In the late Roman Republic, Hispania remained divided like Gaul into a "Nearer" and a "Farther" province, as experienced marching overland from Gaul: Hispania Citerior (the Ebro region), and Ulterior (the Guadalquivir region). The battles in Hispania during the 1st century BC were largely confined to the north.

In the reorganization of the Empire in 14 BC, when Hispania was remade into the three Imperial provinces, Baetica was governed by a proconsul who had formerly been a praetor. Fortune smiled on rich Baetica, which was Baetica Felix, and a dynamic, upwardly-mobile social and economic middling stratum developed there, which absorbed freed slaves and far outnumbered the rich elite. The Senatorial province of Baetica became so secure that no Roman legion was required to be permanently stationed there. Legio VII Gemina was permanently stationed to the north, in Hispania Tarraconensis.

Hispania Baetica was divided into four conventūs, which were territorial divisions like judicial circuits, where the chief men met together at major centers, at fixed times of year, under the eye of the proconsul, to oversee the administration of justice: the conventus Gaditanus (of Gades, or Cádiz), Cordubensis (of Cordoba), Astigitanus (of Astigi, or Écija), and Hispalensis (of Hispalis, or Seville). As the towns became the permanent seats of standing courts during the later Empire, the conventūs were superseded (Justinian's Code, i.40.6) and the term conventus is lastly applied to certain bodies of Roman citizens living in a province, forming a sort of enfranchised corporation, and representing the Roman people in their district as a kind of gentry; and it was from among these that proconsuls generally took their assistants. So in spite of some social upsets, as when Septimius Severus put to death a number of leading Baetians— including women — the elite in Baetica remained a stable class for centuries.

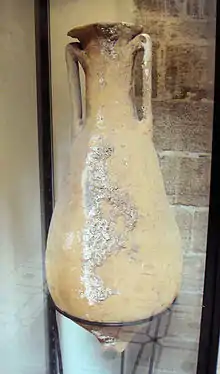

Columella, who wrote a twelve volume treatise on all aspects of Roman farming and knew viticulture, came from Baetica. The vast olive plantations of Baetica shipped olive oil from the coastal ports by sea to supply Roman legions in Germania. Amphoras from Baetica have been found everywhere in the Western Roman empire. It was to keep Roman legions supplied by sea routes that the Empire needed to control the distant coasts of Lusitania and the northern Atlantic coast of Hispania.

Baetica was rich and utterly Romanized, facts that the Emperor Vespasian was rewarding when he granted the Ius latii that extended the rights pertaining to Roman citizenship (latinitas) to the inhabitants of Hispania, an honor that secured the loyalty of the Baetian elite and its middle class. The Roman Emperor Trajan, the first emperor of provincial birth, came from Baetica, though of Italian stock,[1] and his kinsman and successor Hadrian came from a family residing in Baetica, though Hadrian himself was born at Rome (which some say he made up). Baetia was Roman until the brief invasion of the Vandals and Alans passed through in the 5th century, followed by the more permanent kingdom of the Visigoths. The province formed part of the Exarchate of Africa and was joined to Mauretania Tingitana after Belisarius' reconquest of Africa. The Catholic bishops of Baetica, solidly backed by their local population, were able to convert the Arian Visigoth king Reccared and his nobles. In the 8th century the Islamic Berbers ("Moors") of North Africa established the Caliphate of Cordoba, conquering Baetica. The region was known to them as "al-Andalus".

The early 20th-century composer Manuel de Falla wrote a Fantasía Bética for piano, using Andalusian melodies.

Governors

- Marcus Ulpius Traianus, before 67[2]

- Lucius Lucullus, late 70s[3]

- [? Marcus] Sempronius Fuscus, 78/79[4]

- Gaius Cornelius Gallicanus, 79/80

- Lucius Antistius Rusticus, 83/84

- Baebius Massa, 91/92

- Galeo Tettienus Severus Marcus Eppuleius Proculus Tiberius Caepio Hispo, 95/96

- ? Gallus 96/97

- Gaius Caecilius Classicus, 97/98

- Quintus Baebius Macer, 100/101

- Instanius Rufus, 101/102

- ? Lustricius Bruttianus, before 107

- [? Titus] Calestrius Tiro, 107/108

- Egnatius Taurinus, between 117 and 138

- ? Gaius Julius Proculus, 122/123

- Publius Tullius Varro, 123/124

- Lucius Flavius Arrianus, before 129

- Gaius Javolenus Calvinus, between 138 and 143[5]

- Aelius Marcianus, between 138 and 161

- Publius Statius Paullus Postumus Junior, middle of the 2nd century

- Publius Cornelius Anullinus, proconsul c. 170/171

- Gaius Aufidius Victorinus, tenure began 171

- Aulus Caecina Tacitus, first half 3rd century[6]

- L. Sempronius O[...] Celsus [Servi]lius Fabianus, first half 3rd century[7]

- Quintus Pomponius Munat[ianus?] Clodianus, middle of the 3rd century[8]

References

Citations

- Arnold Blumberg, "Great Leaders, Great Tyrants? Contemporary Views of World Rulers who Made History", 1995, Greenwood Publishing Group, p.315

- Paul Leunissen, "Direct Promotions from Proconsul to Consul under the Principate", Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 89 (1991), p. 236

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia 9.48

- Unless otherwise noted, governors from 78/79 to 136/137 are taken from Werner Eck, "Jahres- und Provinzialfasten der senatorischen Statthalter von 69/70 bis 138/139", Chiron, 12 (1982), pp. 281–362; 13 (1983), pp. 147–237.

- Unless otherwise noted, the governors from 138 through 180 are taken from Géza Alföldy, Konsulat und Senatorenstand unter der Antoninen (Bonn: Rudolf Habelt Verlag, 1977), pp. 262f

- Leunissen, "Direct promotions", p. 249

- CIL VI, 15113

- Leunissen, "Direct promotions", pp. 249f

Bibliography

- Carmen Castillo García, Prosopographia Baetica (Collective biographies of Baetica), 1968[1]

- Carmen Castillo García, Städte und Personen der Baetica (Settlements in Baetica), 1975[2]

- A.T. Fear, Rome and Baetica: Urbanization in Southern Spain, C. 50 BC – AD 150 in the series "Oxford Classical Monographs".

- Evan Haley, Baetica Felix: People and Prosperity in Southern Spain from Caesar to Septimius Severus, (excerpt from the Introduction).

- El Housin Helal Ouriachen, 2009, La ciudad bética durante la Antigüedad Tardía. Persistencias y mutaciones locales en relación con la realidad urbana del Mediterraneo y del Atlántico, Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Granada, Granada.

External links

- "Baetica, the great olive oil producer"

- Detailed map of the Pre-Roman Peoples of Iberia (around 200 BC)

- García, Carmen Castillo (1968). Prosopographia Baetica (in Spanish). Universidad de Navarra.

- Castillo, Carmen (1975). Städte und Personen der Baetica (in German). de Gruyter.