Diauehi

Diauehi or Daiaeni[1] (Urartian Diauekhi, Assyrian Diaeni, Greek Taochoi, Armenian Tayk, Georgian Tao) was a tribal union of possibly proto-Armenian,[2][3] Hurrian[4][5][6][7][8] or proto-Kartvelian[9][10][11][12][13][14] groups, located in northeastern Anatolia, that was formed in the 12th century BC in the post-Hittite period. It is mentioned in the Urartian inscriptions.[13] It is usually (though not always) identified with the Yonjalu inscription of the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I's third year (1118 BC).

| History of Georgia |

|---|

|

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Armenia |

Coat of Arms of Armenia |

| Timeline |

According to Robert H. Hewson and Nicholas Adontz, the Daiaeni of Assyrian records lived between Palu and either Taron (modern Mush Province) or Lake Van. They then moved north to Vanand (modern Kars Province), where they battled the Urartians and later encountered Greek mercenaries, including Xenophon. They subsequently moved further northwest.[15]

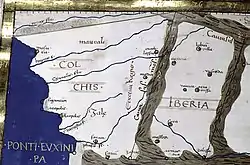

Although the exact geographic extent of Diauehi is still unclear, many scholars place it in the Pasinler Plain in today's northeastern Turkey, while others locate it in the Armenian–Georgian marchlands as it follows the Kura River. Most probably, the core of the Diauehi lands may have extended from the headwaters of the Euphrates into the river valleys of Çoruh to Oltu. The Urartian sources speak of Diauehi's three key cities – Zua, Utu and Sasilu; Zua is frequently identified with Zivin Kale and Utu is probably modern Oltu, while Sasilu is sometimes linked to the early medieval Georgian toponym Sasire, near Tortomi (present-day Tortum, Turkey).[16] The region roughly corresponded to the previous Hayasa-Azzi territory.

Archibald Sayce suggested that Daiaeni was named after an eponymous founder, Diaus.[17] Diauehi is a possible locus of Proto-Kartvelian; it has been described as an "important tribal formation of possible proto-Georgians" by Ronald Grigor Suny (1994).[18]

This federation was powerful enough to counter the Assyrian forays, although in 1112 BC its king, Sien, was defeated by Tiglath-Pileser I (who listed the kingdom as the northernmost point of Nairi[19]). He was captured and later released on terms of vassalage. In 845 BC, Shalmaneser III finally subdued Diauehi and downgraded its king, Asia, to a client ruler.

King Asia of Diauehi (850–825 BC) was forced to submit to the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III in 845 BC, after the latter had overrun Urartu and made a foray into Diauehi. In the early 8th century, Diauehi became the target of the newly emerged regional power of Urartu. Both Menua (810–785 BC) and Argishti I (785–763 BC) campaigned against the Diauehi kingdom. Argishti I defeated King Utupursi(ni), annexing his possessions and in exchange of his life, Utupursi(ni) was forced to pay a tribute including a variety of metals and livestock.[20]

References

- Henri J. M. Claessen; Peter Skalnik; Walter de Gruyter (Jan 1, 1978). The Early State. Mouton Publishers. p. 259. ISBN 9783110813326.

- Hrach Martirosyan (2014). "Origins and Historical Development of the Armenian Language". Leiden University: 9. Retrieved 9 October 2019. p. 8.

- A.V. Dumikyan (2016). "Taik in The Assyrian and Biainian Cuneiform Inscriptions, Ancient Greek and Early Medieval Armenian Sources (the Interpretations of the 19th Century French Armenologists)" Fundamental Armenology No. 2 4.

- Б. А. Арутюнян (1998). "К вопросу об этнической принадлежности населения бассейна реки Чорох в VII—IV вв. до н. э." (PDF). Историко-филологический журнал № 1–2 . С. 233–246. ISSN 0135-0536. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

233. «...К примеру, Г. Тиранян считал, что племена саспейров или эсперитов, фасианов и халдайев (халдеев) или халибов имели, вероятно, картвельское или грузинское происхождение, а таохи — хурритское происхождение.»

246. «Подытоживая вышесказанное, мы приходим к выводу, что бассейн реки Чорох в VII—VII веках до н.э. был населён скифскими племенами, подчинившими местное армянское население, а в районе устья реки Чорох — грузинские племена. Во второй половине I тысячелетия до н.э. они, в основном, оказались в водовороте формирования армянского народа и были арменезированы.» - М. А. Агларов. Дагестан в эпоху великого переселения народов: этногенетические исследования. Институт истории, археологии и этнографии Дагестанского научного центра РАН. p. 191.

31. «Среди специалистов существует мнение, что диаухи-таохи являлись хурритским племенем.»

- М. С. Капица; Л. Б. Алаев; К. З. Ашрафян (1997). "Глава XXIX. Закавказье и сопредельные страны в период эллинизма". История Востока: Восток в древности. Восточная литература. 1. М. p. 530.

«Западное протогрузинское объединение Колхида существовало самостоятельно давно; уже в VIII в. до х.э. оно предположительно унаследовало северные земли уничтоженного урартами хурритского государства таохов, расположенные в долине р. Чорох.»

- А. В. Седов (2004). История древнего Востока. М: Восточная литература. p. 872. ISBN 5020183881.

- И. М. Дьяконов (1968). "Глава II. История Армянского нагорья в эпоху бронзы и раннего железа". Предыстория армянского народа: История Арм. нагорья с 1500 по 500 г. до н. э. Хурриты, лувийцы, протоармяне. Ер.: АН Арм. ССР. p. 120.

«Этническая принадлежность Дайаэни не вполне ясна; Г. А. Меликишвили считает их хурритским племенем, и это весьма вероятно. Но Дайаэни просуществовало до VIII в. до н.э., а следовательно, грузиноязычные халды-халибы, засвидетельствованные западнее, возможно, уже с IX в., должны были бы пройти здесь, скорее всего, раньше его образования, — по всей вероятности, в начале XII в. до н.э...»

- Georgia. (2006). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 14, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service

- Phoenix: The Peoples of the Hills: Ancient Ararat and Caucasus by Charles Burney, David Marshall Lang, Phoenix Press; New Ed edition (December 31, 2001)

- Prince Mikasa no Miya Takahito: Essays on Ancient Anatolia in the Second Millennium B.C. p141

- C. Burney, Die Bergvölker Vorderasiens, Essen 1975, 274

- A. G. Sagona. Archaeology at the North-East Anatolian Frontier, p. 30.

- R. G. Suny. The Making of the Georgian Nation, p. 6.

- Robert. H. Hewson. The Geography of Ananias of Širak: Ašxarhacʻoycʻ, the Long and the Short Recensions. 1992. p. 207. https://archive.org/stream/TheGeographyOfAnaniasOfSirak/The%20Geography%20of%20Ananias%20of%20Sirak_djvu.txt

- G. L. Kavtaradze. An Attempt to Interpret Some Anatolian and Caucasian Ethnonyms of the Classical Sources, p. 80f.

- A.H. Sayce. Cambridge Ancient History, vol. XX. (1925). pp. 169–186.

- Ronald Grigor Suny (1 January 1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation. Indiana University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-253-20915-3.

- "Translation of the Phrygian language". maravot.com.

- Çiftçi, Ali (2017). The Socio-Economic Organisation of the Urartian Kingdom. Brill. pp. 123–125. ISBN 9789004347588.

Further reading

- Antonio Sagona, Claudia Sagona, Archaeology At The North-east Anatolian Frontier, I: An Historical Geography And A Field Survey of the Bayburt Province (Ancient Near Eastern Studies) (Hardcover), Peeters (January 30, 2005), ISBN 90-429-1390-8

- Georgia. (2006). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 14, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service

- Kavtaradze, G. L., "An Attempt to Interpret Some Anatolian and Caucasian Ethnonyms of the Classical Sources", Sprache und Kultur, # 3 (Staatliche Ilia Tschawtschawadse Universitaet Tbilisi für Sprache und Kultur Institut zur Erforschung des westlichen Denkens). Tbilisi, 2002. G. L. Kavtaradze. An Attempt to Interpret Some Anatolian and Caucasian Ethnonyms of the Classical Sources | Anatolia | Hittites

- Melikishvili, G. A., "Diauehi". The Bulletin of Ancient History, vol. 4, 1950. (Publication in Russian)

- (in Russian) С. Д. Гоготидзе, Локализация «стран» Даиаэн-Диаоха.