Cash coins in art

Cash coins are a type of historical Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Ryukyuan, and Vietnamese coin design that was the main basic design for the Chinese cash, Japanese mon, Korean mun, Ryukyuan mon, and Vietnamese văn currencies. The cash coin became the main standard currency of China in 221 BC with the Ban Liang (半兩) and would produced until 1912 AD there with the Minguo Tongbao (民國通寶), the last series of cash coins produced in the world were the French Indochinese Bảo Đại Thông Bảo (保大通寶) during the 1940s.[1] Cash coins are round coins with a square centre hole.[2] It is commonly believed that the early round coins of the Warring States period resembled the ancient jade circles (璧環) which symbolised the supposed round shape of the sky, while the centre hole in this analogy is said to represent the planet earth (天圓地方).[2] The body of these early round coins was called their "flesh" (肉) and the central hole was known as "the good" (好).[2]

| Cash coins in art | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 銅錢紋 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 铜钱纹 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | copper coin motif | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 金錢紋 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 金钱纹 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | gold coin motif | ||||||

| |||||||

While cash coins are no longer produced as official currency today, they remain a common motif in the countries where they once circulated and among the diaspora of those communities. Most commonly cash coins are associated with "good luck" and "wealth" today and are commonly known as "Chinese lucky coins" because of their usage in charms and feng shui. Cash coins also appear in fortune telling and traditional Chinese medicine. Furthermore, cash coins are often found in the logos and emblems of financial institutions in East Asia and Vietnam because of their association with "wealth" and their historical value.

Amulets

Cash coin designs are commonly used as a basic design for various amulets, talismans, and charms throughout the far east, these coin-like amulets often include the general design of cash coins but with different inscriptions.[3][4] Some amulets and charms include may also include images of cash coins as they are associated with "wealth".[5][6] Sometimes images of sycees, another form of ancient Chinese coinage, are used as a symbol in amulets, talismans, and charms for "wealth".[7]

In amulets cash coins can be a symbol not just of "wealth and prosperity", but also the word "before" and of completeness.[5] The latter is because the Mandarin Chinese word for "coin" (錢, qián) sounds like "before" (前, qián).[5] An archaic Mandarin Chinese term for coins (泉, quán) sounds like the word for "complete" (全, quán).[5]

In the island of Bali, Indonesia Pis Bolong (Chinese cash coins) are used as coin-charms and while both authentic and fake Chinese cash coins are used in various rituals and ceremonies by the Balinese Hindu community and used to make souvenir items for tourists, there exist many local versions of the Pis Bolong which are in fact amulets based on these cash coins.[8] It is common for traditional Balinese families to have 200 pieces of Pis Bolong in their household to the point that cash coins could be found in almost every corner of every traditional household on the island.[9]

Architecture

_01.jpg.webp)

Liu Song dynasty tomb

On August 13, 2013 a video broadcast by Hubei TV (HBTV 湖北网台) had revealed the discovery of an ancient tomb dating back to the Liu Song dynasty (Northern and Southern dynasties period) somewhere in June 2013, the tomb was unearthed at a construction site in the city of Xiangyang, Hubei.[10] At this tomb several of its brick display images of Chinese cash coins. Other bricks inside of this tomb display the Chinese character "Wang" (王, "King").[10] According to Liang Chao (梁超), an archaeologist with the Xiangyang Archaeology Institute (襄阳市考古研究所) the bricks with the Chinese character "王" was probably the "logo" or "emblem" of the craftsman who constructed the bricks that were used to make the tomb, and note that perhaps Wang might have been a famous brand of tomb bricks during the Liu Song dynasty period.[10] The owner of the tomb was identified by two bricks which contain the inscription "Nanyang Zong" (南陽宗, nán yáng zōng), which note that the owner was named "Zong" (宗) and originated from the city of Nanyang, Henan.[10] The tomb was identified to have been constructed in the year 461 by an inscription on a brick which reads "Song Da Ming Wu Nian Zao" (宋大明五年造, "Built in the 5th year of the Da Ming reign of the State of Song").[10]

Not a single artifact was discovered inside of the Liu Sog dynasty era tomb which indicates that tomb robbers had looted it sometime in the distant past before its rediscovery.[10]

Luo City Wall

During the Tang dynasty and later the Kingdom of Min periods a city wall in present-day Fuzhou, Fujian was constructed under Wang Shenzhi.[11] The wall is made from bricks that display the design of an ancient Chinese cash coin.[11] Construction of the wall began in the year 901 during the Tang dynasty and continued during the Kingdom of Min.[11]

In the year 2012, about 1,100 years after its construction this wall was unearthed in Fuzhou.[11] Historical records specifically mention the unusual cash coin design on the bricks used to build the "Luo city wall" (羅城, luó chéng) which is how archaeologists managed to identify the wall.[11] Further confirmation that the archaeological find is indeed the famous "Luo City wall" constructed by the Kingdom of Min was later obtained when other bricks at the site were discovered to have the Chinese characters "威武軍" (wēi wǔ jūn), which translates into English as the "Powerful Army", incorporated into their design.[11] Wei Wu Jun was the name of the army Wang Shenzhi commanded.[11] In 2012 the unearthed portions of the "Luo City wall" measures about 74 meters in length and around 8 meters in width.[11]

According to historical records, the "Luo City wall" was severely damaged in battle during the Song dynasty period.[11] During the People's Republic of China period the site where the "Luo City wall" once stood was used as a rubbish dump and would later become the location of a transport station.[11]

Fangyuan Mansion

The famous Taiwanese architect Chu-Yuan Lee had designed the Fangyuan Building (方圓大廈, fāng yuán dà shà) in the city of Shenyang, Liaoning, which was completed in the year 2001.[12] The 25-storey high-rise building is shaped like a stack of ancient Chinese cash coins.[12] The Fangyuan Mansion has been described as one of the world's ugliest buildings.[13][14]

The Fangyuan Mansion has been compared to the later made Guangzhou Circle due to its similar design features.[15]

Taipei 101

The Taipei 101, which was officially classified as the world's tallest building from its opening in 2004 until the 2008 completion of the Shanghai World Financial Center in Shanghai, China,[16][17][18][19] located in the city of Taipei, features a number of designs that are intended to attract good luck, among these architectural features are giant gold coins, in the shape of ancient Chinese cash coins, that adorn all four sides at the base of the tower.[20][21]

Other lucky symbols from traditional Chinese culture incorporated into the design of the Taipei 101 include the fact that the building is divided into eight separate segments, which is an intentional lucky number choice because the number 8 in Mandarin Chinese sounds like the Mandarin word that means "wealthy".[21][20] Furthermore, dragons and "auspicious clouds" decorate the skyscrapers corners.[21]

Bank logos

Several logos of Chinese banks incorporate cash coins into their designs, this is because cash coins have become a cultural icon in China, and the cash coin motif has been incorporated in the logo design of a number of major banks.[22] Some banks also incorporate other forms of ancient Chinese coinage into the designs of their emblems, for example the logo of the People's Bank of China is based on spade money from the Warring States Period.[22]

- The logo of the Bank of China includes in its design the archetypal cash coin motif.[22] It changes the design by instead of incorporating a simple square centre hole, it uses a stylised version of the Chinese character "中" (Zhōng, meaning "middle" or "centre") as an abbreviation for "中國" (Zhōngguó, "central state").[22]

- The logo of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China uses the standard cash coin motif, but instead of having a square centre hole, it uses a stylised version of the Chinese character "工", which translates into English as "commercial".[22] The stylised centre can also be interpreted as being a capital version of the Latin letter "I", representing the English word "industrial".[22] The "centre hole" of the cash coin motif of the logo therefore represents the essence of the bank's name both in English and in Mandarin, the "Industrial and Commercial Bank of China".[22]

- The logo of the China Construction Bank incorporates two Chinese cash coins, which are placed side-by-side with a slight overlap, this overlap gives the image a three-dimensional effect.[22] Furthermore, small piece of the circular design of the cash coins has been removed so that they resemble two of the Latin letter "C".[22] The two "C's" in this design stand for the English name of the bank, "China Construction".[22]

- The logo of the Huaxia Bank incporates the cash coin design by using white space rather than colouring it in.[22] The white space surrounds a gray square and is enclosed by an auspicious red border based on a "jade dragon" from the Hongshan Culture.[22]

The logos of a number of Vietnamese banks incorporate cash coin designs, these include the logos of the VietinBank, National Citizen Bank (Ngân Hàng Quốc Dân), Orient Commercial Joint Stock Bank, and SeABank among others.[23][24]

Banknotes

Imperial Chinese banknotes that were denominated in strings of cash coins often featured designs depicting physical strings of cash coins to showcase their nominal value, usually the higher their denomination was the more cash coins were displayed on the paper note.[25][26][27]

A Tang dynasty era Kaiyuan Tongbao (開元通寳) cash coin appears on the reverse side of a 2010 Hong Kong banknote issued by the Standard Chartered Bank with a face value of $1,000.[28][29]

Bronze mirrors

It was reported on January 5, 2012 a bronze mirror incorporating a cash coin design were discovered during the excavation of a Song dynasty period tomb in Longwan Zhen (龙湾镇), Qianjiang, Hubei.[30][31]

Ceramics

Chinese cash coins were used decoratively and symbolically at least as early as the Han dynasty period, and cash coin designs have been incised into the body of Chinese ceramics as early the Song dynasty period, such as with the Yaozhou meiping vase.[32] But the usage of cash coin designs became more popular during the Ming dynasty period.[32] During the 17th century cash coin-like "base-marks", or dikuan (底款), began to appear using the era names and reign titles of the contemporary monarch.[32] Some of these base-marks are presented in a similar manner as cash coins and may contain inscriptions like Changming Fugui (長命富貴), while others are direct imitations of cash coins and may even include cash coin inscriptions like Hongwu Tongbao (洪武通寶).[32]

Commemorative coins

In 2008 France issued two commemorative coins that featured an image of a Kan'ei Tsūhō (寛永通寳) cash coin on its reverse, one was a silver coin with a nominal value of €1.50 and the other was a gold coin with a nominal value of €10.[33][34]

Flags and banners

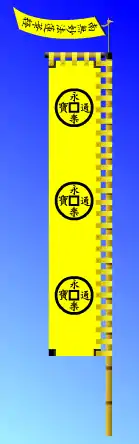

Oda Nobunaga

On the 5th month of the year Eiroku 3 (永禄三, or 1560 in the Gregorian calendar), daimyō Oda Nobunaga was preparing for the Battle of Okehazama and while he had an army of forty thousand men, he could only gather around two and a half thousand soldiers for this decisive battle, Oda Nobunaga then went to pray for a victorious military campaign at the nearby Atsuta-jingū, he asked the Gods to show him a sign that his prayers would be answered and while looking at a handful of Eiraku Tsūhō (永樂通寶) cash coins decided to throw them in the air, when they fell back on the ground they all landed with heads up, he took this as a sign that the Gods would bless him and informed his men that they shall be victorious as they Gods favoured them.[35] After winning the battle he used the Eiraku Tsūhō as a motif for his nobori (a type of flag or banner) and then he had these Eiraku Tsūhō coins inlayed on the tsuba of the sword which he carried during the battle.[35] After Oda Nobunaga's forces were victorious his retainer Hayashi Hidesada said that the Gods must've really spoken through these coins to which Nobunaga replied by saying the Zen Buddhist proverb "I only know that I'm okay with what I got" (吾唯知足, ware tada taru o shiru) and presented to him an Eiraku Tsūhō coin of which both the obverse and reverse sides were heads.[35] Family crests with this proverb written around a square hole resembling a cash coin are not uncommon among military families.[35] Another possibility as to why Oda Nobunaga used Eiraku Tsūhō cash coins as a motif on his nobori was because Eiraku Tsūhō were originally all imported from Ming China during the Muromachi period and spread throughout Japan as the de facto currency, speculation has it that Nobunaga tried to emulate this by having Eiraku Tsūhō as his emblem meaning that his power too shall spread throughout Japan.[35]

The tsuba Oda Nobunaga was carrying during his military campaigns which had the Eiraku Tsūhō inlayed into it was nicknamed the "invincibility tsuba" (まけずの鍔) as he had won all battles he had fought while carrying that tsuba.[35] The Eiraku Tsūhō are divided on this tsuba with 6 being on the omote and 7 of them are displayed on the ura side. This tsuba was declared to be a kokuhō (national treasure) in 1920.[35]

Food and beverages

Doncha

Doncha (돈차; lit. "money tea"),[36] also called jeoncha (전차; 錢茶; lit. "money tea"),[37][38][39] is a cash coin-shaped post-fermented tea produced in Korea. Tea leaves for doncha are hand-picked in May, from the tea plants that grow wild somewhere on the southern coast of the Korean peninsula.[40] Although roasting is the most common method of tea processing in Korea,[41][42] doncha processing starts with steaming the tea leaves.[43] Twelve hours after the harvest, tea leaves are steamed in a gamasot, a traditional cauldron.[39][40] Steamed leaves are then pounded in a jeolgu, a traditional mortar, or a maetdol, a traditional millstone.[38][40] the tea is then shaped into round lumps and sun-dried.[40] Once dried, a hole is made in the center of each lump of tea and they attain the characteristic shape of yeopjeon ("leaf coin" or "cash coin") from which their name is derived.[40] The tea is then fermented for at least six months as aging helps to develop an enriched flavor and aroma, though sometimes fermentation can last for over twenty years.[39][40]

Medals and medallions

- In 1999 artist Mariam Fountain created the Millennium Medal, a "good luck symbol" for the new millennium, its circular shape symbolises the heavens and the medal features a person looking through the square centre hole symbolising the planet earth, the person embraces both the new day and the wide world.[44][45] People wore this medal on January 1st, 2000 as "a prize" for just "being there" during the turn of the millennium.[44] A card initially accompanying the medals for those who purchased it had the statement: "to be worn and polished from hand to hand for the next 1000 years". It notes that the details of the Millennium Medal will eventually be rubbed away, which will accentuate the quintessential symbol of the planet earth and the heavens.[44] The design of the Millennium Medal was later used for the Parisian Franco-British Lawyers Society medal in 2002.[44]

Native American and Alaska natives art

.jpg.webp)

Tlingit body armour

The Tlingits used a body armour made from Chinese cash coins, these coins were introduced by Russian traders from Qing China between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries who traded them for animal skins which were in turn traded with the Chinese for tea, silk, and porcelain by these European traders. The Tlingits believed that these cash coins would protect them from knife attacks and guns used by other indigenous American tribes and Russians. Some Tlingit body armours are completely covered in Qing dynasty era cash coins while others have them sewn in chevron patterns. One Russian account from a battle with the Tlingits in 1792 states "bullets were useless against the Tlingit armour", however this would've more likely be attributed to the inaccuracy of contemporary Russian smoothbore muskets than the body armour and the Chinese coins might've played a more important role in psychological warfare than have any practical application on the battlefield. Other than on their armour the Tlingits also used Chinese cash coins on masks and ceremonial robes such as the Gitxsan dancing cape as these coins were used as a symbol of wealth representing a powerful far away country. The cash coins used by the Tlingit are all from the Qing dynasty are bear inscriptions of the Shunzhi, Kangxi, and Yongzheng Emperors.[46][47][48][49][50]

Playing cards

The earliest Chinese playing cards included designs with a different numbers of cash coins shown on each card.[51] Money-suited decks typically contain 38 cards in four suits, all of which are based on money: cash / coins (tong, 銅/同, ("copper", as in copper-alloy cash coins) or bing, 餅/并, ("cake", as in a cake of silver) or tong 筒 ("bamboo tube").), strings of coins (either suo 索 ("strings of cash") or tiao 條/条 ("strings")), myriads of strings (wan 萬/万, usually accompanied with images of human figures or portraits, sometimes these were heavily abstracted), and tens of myriads (of strings, of coins - 十萬貫).[52][53] The smallest value depict one cash coin per card and the largest one depict ten strings of ten cash coins.[51]

The money-suited cards are believed by some scholars to be an ancestor of the four-suited decks of Islamic and European playing cards.[53]

Sand-drawings

There is a "coin-shaped sand-drawing" or Zenigata suna-e (銭形砂絵) based on the Japanese Kan'ei Tsūhō (寛永通寳) cash coins whose origins date back to 1633 in the Kotohiki Park which lies in Kan'onji, Kagawa Prefecture.[54]

Statues and sculptures

Baoshan National Mining Park

In 2013 a sculpture of a Kaiyuan Tongbao (開元通寳) with a diameter of 24 meters (or 78.7 feet) and a thickness of 3.8 meters (or 12.5 feet) was constructed to be displayed at the Baoshan National Mining Park (宝山国家矿山工园) theme park in the Guiyang Prefecture of Chenzhou, Hunan.[55][56] The sculpture is notably of a Huichang Kaiyuan Tongbao with the Gui (桂) mint mark.[55]

Wuhan

There is a 10 meter tall Kaiyuan Tongbao-shaped door which stands on a bridge in the Jiangxia District of Wuhan, Hubei.[57][58]

Changsha

There are two large sculptures of Kaiyuan Tongbao cash coins at the entrance of the "Exhibition of Chinese Ancient Coins" (traditional Chinese: 中國歷代錢幣展; simplified Chinese: 中国历代钱币展; pinyin: Zhōngguó lìdài qiánbì zhǎn) held at the Ouyang Xun Cultural Park (traditional Chinese: 歐陽詢文化園; simplified Chinese: 欧阳询文化园; pinyin: Ōuyáng xún wénhuà yuán), which is located in Shutang, Wangcheng District, Changsha, Hunan, where on August 17, 1992 by Mr. Ceng Jingyi (traditional Chinese: 曾敬儀; simplified Chinese: 曾敬仪; pinyin: Céng Jìngyí), a retired teacher and coin collector, had unearthed the world's only known authentic specimen of a Tang dynasty period clay mould.[59][60][61]

Store signs

Cash coin designs are sometimes incorporated in Chinese store signs, known as zhāo pái (招牌).[12] Store signs started appearing in China during the Song dynasty period, and by the Ming and Manchu Qing dynasties Chinese shops had developed several types of store signs to help establish their identity.[12] The earliest known Chinese store signs only consisted of a simple piece of cloth with some Traditional Chinese characters on it which was hung at front of the shop's door.[12] These early Chinese store signs would often, only have things like "tea house", "restaurant", or "drugstore" written on them, while some store signs would have the name of the shop or shop owner on it.[12] Other types of imperial Chinese store displayed a sample of the product being sold by the shop to help identify it.[12] For example, a shoe store might hang a shoe from a pole to show that they sell shoes or a tobacco store may display a large wooden model of a tobacco leaf to indicate that they sold tobacco products.[12]

Another type of Chinese store sign design from this period that became popular was those that included symbols of "good luck" and "prosperity", rather than displaying what line of the business the shop was involved in.[12] These store signs would often be based on ancient Chinese cash coins or display an image of Caishen (the Chinese God of Wealth).[12] While store signs shaped like cash coins were common in the past, in modern Chinese metropolises they have become increasingly rare.[12] Cash coin store signs may still be found in Chinese villages and often don't display any symbols associated with the business, often simply displaying cash coin inscriptions and in some cases Chinese numismatic charm inscriptions like Shouxi Facai (壽喜發財, shòu xǐ fā cái) which translates into English as "longevity, happiness, and make a fortune".[12]

Token coins

Plantation tokens in the Dutch East Indies

The Sennah Rubber Co. Ltd. on the island of Sumatra, Netherlands East Indies issued machine-struck token coins that were shaped like cash coins.[62] These tokens were made of brass and were denominated in 5 liters of rice (Dutch: 5 liter rijst).[62] They were 30 millimeters in diameter and had a square central hole that was 8.4 millimeters in diameter.[62]

Yanshoutang pharmacy tokens

In the year 1933 the Yanshoutang (延壽堂) pharmacy in the city of Tianjin issued token coins that were shaped like cash coins.[63] These pharmacy tokens were made from silver and were Ø 32 millimeters.[63] The large obverse inscription around the square centre hole reads Yan Nian Yi Shou (延年益壽) which translates into English as "To live an extended life".[63] The top of the obverse side of the token has the text Yanshoutang Yaopu (延壽堂藥鋪) which means "Yanshoutang pharmacy" written from right to left inside of the rim of the coin.[63] The bottom of the reverse side reads Tianjin Fajie Majialou Nan (天津法界馬家樓南) which translates into English to "South of the Ma (馬) family building, French concession of Tianjin".[63] The large reverse inscription of these silver pharmacy tokens around the square centre hole read Yi Yuan Qian Zeng (一元錢贈), which translates into English as "Gift of 1 yuan".[63] At the top part of the rim it reads Yishi Bo Qi Sun Shengchang Faming (醫士伯岐孫盛昌發明) written from right to left which translates into English as "Doctor Bo Qi and Sun Shengchang inventors", while the inscription at the bottom of the rim reads Kaishi Jinian (開始紀念), which translates as "Commemorating the opening".[63] On the right and left side of the rim are Chinese characters Gui-You (癸酉) which indicates that it was produced in 1933.[63]

Tong-in Market Yeopjeon tokens

At the Tong-in Market (통인시장), a small market that was established in 1941 during the Japanese occupation period for Seoul's Japanese residents outside of the Gyeongbok Palace, people can purchase token coins shaped like yeopjeon ("leaf coins", the Korean tern for cash coins) at shops which are members of the "Dosirak Café" (도시락) project to spend at around 70 food stores and restaurants. The shops where these yeopjeon tokens can be spent have a sign stating "通 도시락 cafe" and these tokens can be bought in strings of 10 yeopjeon. A single one of these yeopjeon tokens cost ₩500 in 2014.[64][65]

Shingi Tongbo

At the Shingi market (신기시장, 新起市場 or 新基市場) located in the city of Incheon, South Korea cash coin-shaped token coins made from brass can be used to pay for items.[66] These tokens have the obverse inscription Shingi Tongbo (新起通寶) and the reverse inscription O Baek (五百, written from left to right), these Chinese characters indicate that each Shingi Tongbo token is equivalent to ₩ 500 (which was valued at $ 0.40 in the year 2019).[66] Foreign visitors are given 6 Shingi Tongbo token coins free of charge when entering the market (as of 2019),[66] tourists are given these cash coin-shaped tokens so that they can experience trading with ancient money.[67]

Furthermore, the entrance to the Shingi market is shaped like an elongated cash coin with the Chinese characters inscribed on it on both ends of the sign and the name of the market written in Hangul in the middle.[66]

Mikazuki-mura Edo coins

Cash coin tokens are used at the Mikazuki-mura (三日月村) theme park located in the Gunma Prefecture, Kantō region.[68] The theme park is based on a rural village during the Bakumatsu (the late Edo period) and includes a number of attractions such as a house filled with Ninja tricks.[68] On the premises of the Mikazuki-mura theme park visitors have to use "Edo coins" to make purchases as well as to pay for the attractions.[69][68] These tokens are purchased at a price of 100 yen (円) for 1 mon (文).[69] The tokens are identical to the historical Edo period Kan'ei Tsūhō (寛永通寳) and Tenpō Tsūhō (天保通寳) cash coins, but contain the text "三日月村" (Mikazuki-mura) written very small on their reverse sides.[69]

Video games

The Tenpō Tsūhō (天保通寳) is a collectable item in the 2013 American video game Tomb Raider, which can be obtained inside the Cliffside Bunker on Yamatai.[70][71]

Zodiacs

The Chinese zodiac "rat" (鼠) is often depicted holding a cash coin.[72] This is because in Chinese folklore, there is a story that once upon a time, five beautiful fairies descended to the world of the mortals and had disguised as rats.[72] These fairies in rat form then gathered sycees and cash coins, and later gave all these treasures to the people.[72] This is why the rats from the Year of the Rat (鼠年) are sometimes referred to as "money-gathering rats".[72]

Gallery

.jpg.webp)

A Balinese statuette of a woman made from Qing dynasty period cash coins on display at the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam.

A Balinese statuette of a woman made from Qing dynasty period cash coins on display at the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam._01.jpg.webp) A 1 dollar banknote issued by the Shanghai branch of the China Specie Bank Ltd. in 1922, note that the cash coin inscription reads Zhonghua Guobao (中華國寶), which translates into English as "Chinese national treasure".

A 1 dollar banknote issued by the Shanghai branch of the China Specie Bank Ltd. in 1922, note that the cash coin inscription reads Zhonghua Guobao (中華國寶), which translates into English as "Chinese national treasure"._01.jpg.webp) A 5 dollars banknote issued by the Shanghai branch of the China Specie Bank Ltd. in 1922, note that the cash coin inscription reads Zhonghua Guobao (中華國寶), which translates into English as "Chinese national treasure".

A 5 dollars banknote issued by the Shanghai branch of the China Specie Bank Ltd. in 1922, note that the cash coin inscription reads Zhonghua Guobao (中華國寶), which translates into English as "Chinese national treasure". An Industrial and Commercial Bank of China branch office in Altai City, Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang.

An Industrial and Commercial Bank of China branch office in Altai City, Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang.

.jpg.webp) A photograph of a young Wishram woman in bridal garb. Note the Qing dynasty cash coins in her headdress.

A photograph of a young Wishram woman in bridal garb. Note the Qing dynasty cash coins in her headdress. Tlingit body armour made with Chinese cash coins on display at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States.

Tlingit body armour made with Chinese cash coins on display at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. The coin-shaped sand-drawing" or Zenigata suna-e (銭形砂絵) based on the Japanese Kan'ei Tsūhō (寛永通寳) cash coins whose origins date back to 1633 in the Kotohiki Park which lies in Kan'onji, Kagawa Prefecture.

The coin-shaped sand-drawing" or Zenigata suna-e (銭形砂絵) based on the Japanese Kan'ei Tsūhō (寛永通寳) cash coins whose origins date back to 1633 in the Kotohiki Park which lies in Kan'onji, Kagawa Prefecture. The former flag of Kan'onji, Kagawa.

The former flag of Kan'onji, Kagawa. The former emblem of Kan'onji, Kagawa.

The former emblem of Kan'onji, Kagawa. The mon (紋 "family crest") of the Sengoku clan.

The mon (紋 "family crest") of the Sengoku clan.

References

- "Sapeque and Sapeque-Like Coins in Cochinchina and Indochina (交趾支那和印度支那穿孔錢幣)". Howard A. Daniel III (The Journal of East Asian Numismatics – Second issue). 20 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "huanqian 圜錢, round coins of the Warring States and the Qin Periods". By Ulrich Theobald (Chinaknowledge). 24 June 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "Chinese Charm Inscriptions". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 16 November 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Craig Greenbaum (2006). "Amulets of Viet Nam (Bùa Việt-Nam - 越南符銭)". Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "The Hidden or Implied Meaning of Chinese Charm Symbols - 諧音寓意 - Differences between Chinese Coins and Chinese Charms". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 16 November 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- China Buddhist Encyclopedia The Hidden or Implied Meaning of Chinese Charm Symbols copied from Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). Retrieved: 1 April 2020.

- "Not Being Greedy Is a Treasure". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 6 January 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Bali Around (Bali Hotels and Travel Guide by Baliaround.com). (2008). "Chinese Coins in Balinese Life". Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Uang-Kedaluwarsa (January 2010). "Mengenal Koin gobob" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- "Bricks with Coin Design Discovered in Southern Dynasty Tomb". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 30 August 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Coin Design Discovered on Wall Bricks from Kingdom of Min". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 22 February 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "Store Signs of Ancient Chinese Coins". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 11 September 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Bunny Wong (29 October 2009). "The World's Ugliest Buildings". Travel + Leisure Group. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

This 25-floor office building, finished in 2001 in the northeastern capital of Liaoning Province, is a weird mishmash of ideas. One is a reference to old Chinese coins, which have square cutouts—just like the structure’s square center. Other parts of the design are like a garden-variety corporate building, with a concrete base and, on the sides, steel rims with glass grooves. The Ugly Truth: Princeton-educated Taiwanese architect C. Y. Lee, who designed Taipei 101 (the world’s tallest building until last year), wanted to meld East and West. In this creation, urban concrete-and-steel commercial structure meets ancient Chinese currency.

- Fauna (12 January 2012). "Shengyang Fangyuan Makes CNN's World's 10 Ugliest Buildings List". chinaSMACK. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Guangzhou Circle building - what, where, how". gohongkong.about.com. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- "World's fastest elevator: In Taiwan, the skyscraper's elevator travels at 60 km/h". Toronto Star. 23 January 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- 2001-10: Wins the contract for Taipei 101 (101 levels, 508 meters), then the world's tallest building. History - Company - Samsung C&T

- "Building Taipei 101". 18 January 2013.

- "Samsung C&T". Lakhta Center.

- Ciaran McEneaney (8 January 2019). "A Brief History of Taiwan's Taipei 101". The Culture Trip (Theculturetrip.com). Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- Avery Trufelman (19 April 2016). "Episode 209 - Supertall 101". 99% Invisivle. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Chinese Coins and Bank Logos". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 10 February 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Unlisted (December 2016). "Ý nghĩa đằng sau logo của các ngân hàng Việt Nam" (in Vietnamese). GiangBLOG. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Unlisted (10 September 2015). "Tổng hợp logo của các ngân hàng tại Việt Nam (phần 2)" (in Vietnamese). Designs.vn. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- John E. Sandrock (2018). "Ancient Chinese Cash Notes - The World's First Paper Money - Part II" (PDF). The Currency Collector. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Google Arts & Culture - Chinese Ming Banknote from the collection of the British Museum. Retrieved: 14 September 2018.

- The British Museum - Ming dynasty paper money: scientific analysis -The inclusion of a fourteenth-century Ming note in “A History of the World in 100 Objects” has brought unprecedented attention to these objects by Dr. Helen Wang. Retrieved: 14 September 2018.

- Standard Chartered Bank (Hong Kong). "Standard Chartered Bank (Hong Kong) Limited 2010 New Series Hong Kong Banknotes" (PDF). Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Sarah Lazarus (25 October 2014). "Henry Steiner: the king of graphic design - You've seen Henry Steiner's work. It stares at you from billboards, banks and other buildings - it's even lurking in your pocket. Sarah Lazarus meets the father of Hong Kong graphic design as he celebrates his company's 50th anniversary". Post Magazine. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- "Chinese Coin Mirror Discovered in Song Dynasty Tomb". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 5 January 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- 荆楚网 (5 January 2012). "潜江发掘一座宋代墓葬 出土十多种年号钱币" (in Chinese). China News Hubei. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Dr. Helen Wang (29 March 2020). "75. Chinese coins and reign/base marks on ceramics". Chinese Money Matters (The British Museum). Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Numista 1½ Euro Kan'ei Tsuho. Retrieved: 04 July 2018.

- Die €uro-Münzen (2016 edition). Publisher: Gietl Verlag. Page = 223. (in German).

- "The "invincibility tsuba"". by Markus Sesko (Markus Sesko - Translation and Research Services for Japanese Art and Antiques.). 30 May 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- "doncha" 돈차. Standard Korean Language Dictionary. National Institute of Korean Language. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- "jeoncha" 전차. Standard Korean Language Dictionary. National Institute of Korean Language. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- 이, 영근 (9 April 2014). "[국내여행]그 분을 만나러 가는 여행…장흥돈차 청태전 복원 주인공 '김수희'". Maeil Business Newspaper (in Korean). Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- "Don Tea". Slow Food Foundation. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- 김, 성윤 (2 October 2013). "[오늘의 세상] '맛의 방주(사라질 위기에 처한 먹거리를 보존하려 만든 목록)'에 오른 돈차(엽전 모양으로 빚은 茶)·烏鷄(온몸이 검은 닭)… 한국 토종 먹거리의 재발견". The Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- 정, 동효; 윤, 백현; 이, 영희, eds. (2012). "deokkeum-cha" 덖음차. 차생활문화대전 (in Korean). Seoul: Hong Ik Jae. ISBN 9788971433515. Retrieved 22 March 2017 – via Naver.

- 정, 동효; 윤, 백현; 이, 영희, eds. (2012). "bucho-cha" 부초차. 차생활문화대전 (in Korean). Seoul: Hong Ik Jae. ISBN 9788971433515. Retrieved 22 March 2017 – via Naver.

- 정, 동효; 윤, 백현; 이, 영희, eds. (2012). "jeungje-cha" 증제차. 차생활문화대전 (in Korean). Seoul: Hong Ik Jae. ISBN 9788971433515. Retrieved 22 March 2017 – via Naver.

- Dr. Helen Wang (17 August 2018). "53. The Millenium Medal, by Marian Fountain". Chinese Money Matters (The British Museum). Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Pièces chinoises by Laurent Zylberman. Published: 20 Août 2018. Retrieved: 01 April 2020. (in French).

- "Body Armor Made of Old Chinese Coins". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 1 February 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "27. Chinese coins on Tlingit armour". Chinese Money Matters (The British Museum). 11 September 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Alaskan Tlingit Body Armor Made of Coins". Everett Millman (Gainesville News – Precious Metal, Financial, and Commodities News). 23 September 2017. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Ancient Chinese Coin Brought Good Luck in Yukon". Rossella Lorenzi (for the Discovery Channel) – Hosted on NBC News. 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "17th-century Chinese coin found in Yukon - Russian traders linked China with First Nations". CBC News. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- Heather (2021). "History of Chinese Playing Cards". Learn Chinese History™ - Where the Middle Kingdom comes alive.™. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Chinese Money-Suited Playing Cards". The Mahjong Tile Set - This site has had 1524094 hits since 19/04/2013. 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Dan Nosowitz (13 July 2020). "Playing Cards Around the World and Through the Ages. - The complicated lineage of our ubiquitous decks". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Hello Japan Zenigata Sand Painting (Kotohiki Park). Retrieved: 04 July 2018.

- Gary Ashkenazy ( גארי אשכנזי ) (3 September 2013). "World's Largest Copper Coin Sculpture". Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- News.Changsha.cn (30 August 2013). "世界最大铜钱币雕塑落户郴州桂阳 直径24米。" (in Chinese). Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Photograph: VCG/VCG via Getty Images. (18 May 2016). "The odd, odd world we live in!". Rediff.com. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Houze Song, Derek Scissors, and Yukon Huang (24 May 2016). "Is China on a Path to Debt Ruin? There's still a chance to avoid the worst. It depends on how bold the government is willing to be". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 6 April 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "'Kai Yuan Tong Bao' Clay Mould". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 18 January 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- 曾敬仪 (January 1993). "湖南望城出土开元通宝残陶范" (in Chinese). 同方知网数字出版技术股份有限公司. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Unlisted (6 January 2015). "77岁钱痴收藏7000枚古钱币 含夏商时代贝币(图)" (in Chinese). Sina Corp. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Baldwin's Hong Kong Coin Auction (23 August 2012). "COINS. INDONESIA – SUMATRA. Plantation Tokens. Sennah Rubber Co Ltd: Brass 5-Liter ryst (rice), 30mm, square central hole 8.4mm (LaWe 433 RRR). Good fine. - Estimate: US$140-180". NumisBids. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- François Thierry de Crussol (蒂埃里) (14 September 2015). "Jeton de la pharmacie Yanshoutang 延壽堂 (Tien-tsin 天津). - Yanshoutang 延壽堂 Pharmacy token (Tianjin)" (in French). TransAsiart. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Jeon Han, Sohn JiAe (4 March 2014). "Tongin Market draws tourists to the heart of Seoul". Korea.net. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- Wanderluster (28 November 2014). "Tong-in Market Dosirak Cafe: $5 Korean Lunchbox. (The Calm Chronicle - Your South Korea & World Travel Guides Curated by a Wanderluster. - By Pheuron Korea: Street Food & Markets, Seoul, Seoul: Gyeongbok Palace area, South Korea - November 28, 2014)". Pheurontay. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- "Shingi Market". Hotel Skypark Incheon Songdo. 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Unlisted (2020). "The Best Markets In Incheon, South Korea § Shin Gi Market". The Culture Trip. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- All around GUNMA (Filled with tons of information about Gunma) (September 2014). "This month's recommendation - Mikazuki-mura". Gunma Association of Tourism, Local Products & International Exchange (International Relations). Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- 大吉 (11 June 2014). "2014年06月11日 - 珍品!?寛永通宝を買い取りました!- こんにちは!- 本日は先日買取させて頂いた珍商品をご紹介します。- 寛永通宝 (三日月村)" (in Japanese). Kaitori-Daikichi.jp. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Arte-Factual: 100 Mon Coin (Tomb Raider 2013)". Kelly M. (The Archeology of Tomb Raider). 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017.

- IGN 100 Mon Coin (Tomb Raider 2013) Imagine Games Network (Ziff Davis, LLC – j2 Global, Inc.) Retrieved: 11 June 2017.

- Huang Zhiling (3 March 2020). "Exquisite design marks Year of the Rat mug by award-winning designer". China Daily (Chinese Communist Party Central Committee Propaganda Department). Retrieved 1 April 2020.

Sources

- Hartill, David (September 22, 2005). Cast Chinese Coins. Trafford, United Kingdom: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1412054669.

- Hartill, David, Qing cash, Royal Numismatic Society Special Publication 37, London, 2003.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cash coins in art. |

.jpg.webp)

_-_Art-Hanoi_01.jpg.webp)