Christian Democratic People's Party of Switzerland

The Christian Democratic People's Party of Switzerland (German: Christlichdemokratische Volkspartei der Schweiz, CVP; French: Parti démocrate-chrétien, PDC; Italian: Partito Popolare Democratico, PPD; Romansh: ![]() Partida cristiandemocratica Svizra , PCD) was a Christian-democratic political party in Switzerland.[8] On January 1, 2021, the party merged with the Conservative Democratic Party of Switzerland (BDP) to form The Center, which will operate at the federal level. The party will continue to exist at the cantonal level as individual local and regional parties determine their status.

Partida cristiandemocratica Svizra , PCD) was a Christian-democratic political party in Switzerland.[8] On January 1, 2021, the party merged with the Conservative Democratic Party of Switzerland (BDP) to form The Center, which will operate at the federal level. The party will continue to exist at the cantonal level as individual local and regional parties determine their status.

| |

| President | Gerhard Pfister |

| Vice Presidents | Ida Glanzmann, Charles Juillard |

| General Secretary | Gianna Luzio |

| Members in Federal Council | Viola Amherd |

| Founded | 1912 |

| Dissolved | 31 December 2020 |

| Merged into | The Center |

| Headquarters | Hirschengraben 9 CH-3011 Bern |

| Youth wing | Young CVP |

| Membership (2015) | 100,000[1] |

| Ideology | Christian democracy[2] Social conservatism Support for EU Bilateral Accords |

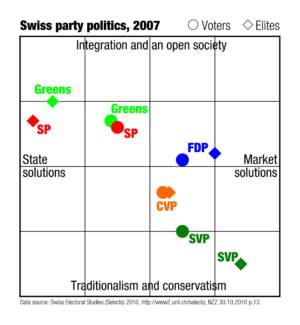

| Political position | Centre[3][4][5] to centre-right[6][7] |

| European affiliation | European People's Party (associate) |

| Colours | Orange |

| Federal Council | 1 / 7 |

| National Council | 25 / 200 |

| Council of States | 13 / 46 |

| Cantonal executives | 40 / 154 |

| Cantonal legislatures | 435 / 2,609 |

| Website | |

| www | |

Its 28 seats in the National Council and 13 seats in the Council of States merged into the new party as has its single seat . It has one seat on the Swiss Federal Council, which was held by Viola Amherd.

The party was founded as the Catholic Conservative Party in 1912. The party peaked in the 1950s, having three members of the Federal Council (1954–58) before agreeing to the Magic formula. It adopted its current name in 1970. From 1979 to 2003, the party's vote declined, mostly in the favour of the Swiss People's Party, and the party was reduced to one Federal Councillor at the 2003 election.

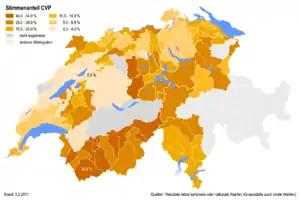

The party sits in the centre to centre-right of the political spectrum, advocating Christian democracy, the social market economy, and moderate social conservatism. The party was strongest in Catholic rural areas, particularly Central Switzerland and Valais.

History

In 1912 the Catholic-Conservative Party of Switzerland (German: Katholisch-Konservative Partei der Schweiz) was founded. From 1919 on, the party occupied two out of the seven seats in the cabinet. Aided by the political climate of the postwar period, the party experienced its peak in the 1950s: It was represented by the biggest parliamentary delegation in the national assembly, and from 1954 to 1958 the party occupied three out of seven seats in the cabinet. Nonetheless, the party had to relinquish the third seat in favor of the 'Magic formula', which was introduced to the cabinet in 1959. In 1957 it changed its name to the Conservative-Christian-Social People's Party (German: Konservativ-Christlichsoziale Volkspartei) and to its current name in 1970. In the ensuing decades, the Catholic voter base dissolved somewhat. The reduction of the voter base, in addition to less cohesion among politicians in the party, led to six successive losses in federal elections after 1980.

The party lost its support over a number of years. Beginning in the 1990s, conservative voters from former strongholds of the CVP switched to vote for the right-wing populist Swiss People's Party. From the 1995 election to the 2019 election, the CVP's vote share decreased from 16.8% to 11.4%.[9] After the 2003 election, Ruth Metzler of the CVP, was replaced by Christoph Blocher of the Swiss People's Party on the Federal Council, leaving the CVP with only one seat in the country's executive.[10]

CVP President Gerhard Pfister and BDP President Martin Landolt, the leader of the Conservative Democratic Party, had ongoing discussions about a merger throughout 2020.[11][12] In 2020, Pfister announced that the national CVP would undergo a change in branding with a new name and logo as part of a merger with the BDP. The party proposed to change the name to "The Center" or "The Alliance of the Center" (German: Die Mitte, CVP; French: Le Centre, PDC; Italian: Alleanza del Centro, PPD; Romansh: Allianza dal Center) which is the name of the parliamentary group that the CVP shares with the other center-right parties, the Conservative Democratic Party of Switzerland and the Evangelical People's Party of Switzerland. [13] The merger was ratified by a vote of the entire party in November 2020. Cantonal parties were not required to adopt the new name if they do not wish to do so.[9] Pfister estimated that a new center-right party could obtain up to 20% of the vote in future elections.[14]

Party platform

In its party platform, the CVP described itself as a centrist party. The CVP fostered a social market economy in which a balance is struck between economic liberalism and social justice. The expansion of the party in the Protestant-dominated cantons, in which the CVP uphold rather centrist policies, stands in contrast to the traditional role of the CVP as the leading party in rather Catholic-dominated cantons of central Switzerland, and the cantons of Valais. There, the electorate was mostly socially conservative.

The CVP had three main policies in the political centre:

- The CVP uphold the social market economy. It supports exporting industries, more spending on education, research and development. It also aims at combating the black market and tax evasion. In order to increase efficiency and incentives, the CVP calls for the reduction and streamlining of bureaucratic procedures and government agencies, low taxation for family enterprises and those who offer vocational education and internships. The CVP calls for equal wages and job opportunities for both men and women.

- The CVP called for flexible working times, childcare, and affordable housing.

- The CVP aimed at ensuring social security. The CVP calls for reforms of the social security system, by raising taxes on demerit goods (e.g. tobacco taxes) to generate more revenues for the pension funds. The retirement age of 65 should also be upheld. The public health care system shall be streamlined by a reduction of waiting times of medical procedures, in order to ensure equitable services. The CVP also promotes workfare as the primary means to combat unemployment.

Popular support

Following continuing losses in the federal parliamentary elections until 2003, in December 2003, the party lost one of its two seats in the four-party coalition government, the Swiss Federal Council, to the Swiss People's Party. The CVP holds roughly 12% of the popular vote.

After the national election in late 2003, it held 28 seats (out of 200) in the Swiss National Council (first chamber of the Swiss parliament); 15 (out of 46) in the Council of States (second chamber, and the largest party in this chamber) and 1 out of 7 seats in the Swiss Federal Council (executive body).

In 2005, it held 20.7% of the seats in the Swiss Cantonal governments and 16.7% in the Swiss Cantonal parliaments (index "BADAC", weighted with the population and number of seats). At the last legislative national elections, 22 October 2007, the party won 14.6% of the popular vote and 31 out of 200 seats in the National Council lower house.[16] This was a gain of 3 seats, ending the long-term decline of the party and it was the only one of the four largest parties besides the Swiss People's Party to gain votes and seats.

In the Federal Assembly, the CVP formerly sat in a bloc in the Christian Democrats/EPP/glp Group, along with the Evangelical People's Party and Green Liberal Party.[17]

Election results

| Year | Votes | % | Seats | +/- |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 | 71,668 | 21.1 | 37 / 189 |

|

| 1917 | 84,784 | 16.4 | 42 / 189 |

|

| 1919 | 156,702 | 21.0 | 41 / 189 |

|

| 1922 | 153,836 | 20.9 | 44 / 198 |

|

| 1925 | 155,467 | 20.9 | 42 / 198 |

|

| 1928 | 172,516 | 21.4 | 46 / 198 |

|

| 1931 | 184,602 | 21.4 | 44 / 187 |

|

| 1935 | 185,052 | 20.3 | 42 / 187 |

|

| 1939 | 105,018 | 17.0 | 43 / 187 |

|

| 1943 | 182,916 | 20.8 | 43 / 194 |

|

| 1947 | 203,202 | 21.2 | 44 / 194 |

|

| 1951 | 216,616 | 22.5 | 48 / 196 |

|

| 1955 | 226,122 | 23.2 | 47 / 196 |

|

| 1959 | 229,088 | 23.3 | 47 / 196 |

|

| 1963 | 225,160 | 23.4 | 48 / 200 |

|

| 1967 | 219,184 | 22.1 | 45 / 200 |

|

| 1971 | 407,225 | 20.4 | 44 / 200 |

|

| 1975 | 407,286 | 21.1 | 46 / 200 |

|

| 1979 | 390,281 | 21.3 | 44 / 200 |

|

| 1983 | 396,281 | 20.2 | 42 / 200 |

|

| 1987 | 378,822 | 19.6 | 42 / 200 |

|

| 1991 | 367,928 | 18.0 | 35 / 200 |

|

| 1995 | 319,972 | 16.8 | 34 / 200 |

|

| 1999 | 309,118 | 15.8 | 35 / 200 |

|

| 2003 | 301,652 | 14.4 | 28 / 200 |

|

| 2007 | 335,623 | 14.5 | 31 / 200 |

|

| 2011 | 300,544 | 12.3 | 28 / 200 |

|

| 2015 | 293,653 | 11.6 | 27 / 200 |

|

| 2019 | 275,842 | 11.4 | 25 / 200 |

Party strength over time

| Canton | 1971 | 1975 | 1979 | 1983 | 1987 | 1991 | 1995 | 1999 | 2003 | 2007 | 2011 | 2015 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switzerland | 20.3 | 21.1 | 21.3 | 20.2 | 19.6 | 18.0 | 16.8 | 15.9 | 14.4 | 14.5 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 11.4 |

| Zürich | 9.5 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 5.9 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 7.6 | 5.0 | 4.2 | 4.4 |

| Bern | 5.3 | 5.3 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 4.7 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Luzern | 48.8 | 50.1 | 50.4 | 49.6 | 47.0 | 48.6 | 37.3 | 33.8 | 29.5 | 30.2 | 27.1 | 23.9 | 25.5 |

| Uri | *a | 18.6 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 26.8 | 39.2 |

| Schwyz | 38.5 | 46.4 | 49.4 | 46.6 | 36.9 | 32.8 | 27.4 | 27.3 | 23.4 | 20.1 | 20.6 | 19.5 | 18.4 |

| Obwalden | 67.0 | 97.1 | 95.7 | 91.0 | 51.7 | 95.3 | 94.2 | * | 66.4 | 32.5 | * | * | 36.7 |

| Nidwalden | 97.2 | 97.6 | 49.5 | 97.2 | 96.9 | 97.7 | 32.1 | * | * | * | * | * | 35.8 |

| Glarus | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Zug | * | 39.4 | 34.1 | 39.9 | 34.2 | 34.2 | 27.1 | 26.4 | 22.9 | 23.3 | 24.3 | 26.4 | 23.8 |

| Fribourg | 41.5 | 46.9 | 39.9 | 37.9 | 37.7 | 36.8 | 36.0 | 33.7 | 25.4 | 24.8 | 20.3 | 22.7 | 17.8 |

| Solothurn | 27.7 | 26.0 | 27.6 | 26.7 | 25.1 | 22.2 | 21.5 | 21.4 | 21.0 | 20.4 | 17.9 | 14.8 | 14.2 |

| Basel-Stadt | 11.2 | 12.1 | 13.9 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 10.4 | 9.7 | 8.6 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 4.6 |

| Basel-Landschaft | 13.3 | 13.3 | 11.5 | 10.8 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 11.7 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 11.4 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 8.5 |

| Schaffhausen | 8.0 | * | * | 6.3 | * | * | * | * | 2.7 | * | 5.2 | * | 2.1 |

| Appenzell A.Rh. | * | 14.1 | * | 14.5 | * | 16.7 | 9.5 | * | * | * | 10.6 | * | * |

| Appenzell I.Rh. | 96.1 | 98.3 | 97.2 | 95.6 | 91.8 | 98.7 | 85.4 | 73.5 | 69.2 | 84.6 | 76.1 | 76.3 | 61.3 |

| St. Gallen | 44.0 | 43.3 | 44.1 | 40.8 | 39.4 | 35.8 | 31.0 | 26.2 | 22.2 | 21.4 | 20.3 | 16.6 | 18.8 |

| Graubünden | 37.3 | 35.9 | 35.5 | 33.3 | 28.5 | 25.6 | 26.9 | 25.6 | 23.7 | 20.3 | 16.6 | 16.8 | 16.3 |

| Aargau | 20.0 | 20.6 | 22.5 | 21.5 | 18.9 | 14.5 | 14.2 | 16.3 | 15.6 | 13.5 | 10.6 | 8.6 | 9.9 |

| Thurgau | 23.4 | 22.3 | 24.6 | 21.6 | 20.4 | 16.5 | 13.0 | 15.7 | 16.5 | 15.2 | 14.4 | 13.1 | 12.7 |

| Ticino | 34.8 | 35.7 | 34.1 | 34.0 | 38.2 | 26.9 | 28.4 | 25.9 | 24.6 | 24.1 | 20.0 | 20.1 | 18.2 |

| Vaud | 5.3 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 5.6 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 2.4 |

| Valais | 61.5 | 59.7 | 58.8 | 57.5 | 58.7 | 54.3 | 54.8 | 51.4 | 47.9 | 44.9 | 39.9 | 39.8 | 34.8 |

| Neuchâtel | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 4.2 |

| Genève | 13.8 | 14.7 | 14.0 | 12.3 | 14.6 | 14.5 | 13.4 | 14.1 | 11.8 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 12.1 | 7.7 |

| Jura | b | b | 37.7 | 25.1 | 33.0 | 36.0 | 38.2 | 39.2 | 39.5 | 25.0 | 33.2 | 27.6 | 22.8 |

Presidents

- 1986–1992 Eva Segmüller, St. Gallen

- 1992–1994 Carlo Schmid-Sutter, Appenzell Innerrhoden

- 1994–1997 Anton Cottier, Fribourg

- 1997–2001 Adalbert Durrer, Obwalden

- 2001–2004 Philipp Stähelin, Thurgau

- 2004–2006 Doris Leuthard, Aargau

- 2006-2016 Christophe Darbellay, Valais

- 2016–2020 Gerhard Pfister, Zug

Secretaries-General

- 1988–1992 Iwan Rickenbacher

- 1992–1997 Raymond Loretan

- 1997–2001 Hilmar Gernet

- 2001–2008 Reto Nause

- 2009–2012 Tim Frey

- 2012–2018 Béatrice Wertli

- 2018–2020 Gianna Luzio

Notes and references

- The Swiss Confederation – A Brief Guide. Federal Chancellery. 2015. p. 19. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2019). "Switzerland". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Altermatt, Urs (2013). CVP: Von der katholischen Milieupartei zur Partei der bürgerlichen Mitte. Die Parteien in Bewegung: Nachbarschaft und Konflikte. Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung. pp. 36–37.

- Burlacu, Diana; Tóka, Gábor (2014). Policy-based Voting and the Type of Democracy. Elections and Democracy: Representation and Accountability. Oxford University Press.

- Budge, Ian; Keman, Hans; McDonald, Michael D.; Pennings, Paul (2012). Organizing Democratic Choice: Party Representation Over Time. Oxford University Press. p. 134.

- Damir Skenderovic (2009). The Radical Right in Switzerland: Continuity and Change, 1945-2000. Berghahn Books. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-84545-948-2. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Freedom House (1 December 2011). Freedom in the World 2011: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 649. ISBN 978-1-4422-0996-1.

- Philip Manow; Kees van Kersbergen (2009). Religion and the Western Welfare State—The Theoretical Context. Religion, Class Coalitions, and Welfare States. Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-521-89791-4. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- "Die CVP soll neu «Die Mitte» heissen" (in German). SRF. 4 September 2020.

- "Assemblée du PDC: «Le Centre peut atteindre 20% et se renforcer à l'exécutif en 2027»". Le Nouvelliste (in French). 5 September 2020.

- "BDP will mit Statutenänderung Weg für Fusion ebnen" (in German). Nau.ch. 5 September 2020.

- "Martin Landolt und Gerhard Pfister bereiten BDP-CVP-Fusion vor" (in German). Nau.ch. 28 May 2020.

- "CVP soll neu «Die Mitte» heissen" (in German). Telebasel. 4 September 2020.

- "«Die Mitte»: CVP präsentiert neuen Namen und Logo". Nau.ch (in German). 4 September 2020.

- The data is based on research by Philipp Leimgruber (University of Bern), Dominik Hangartner (Washington University) and Lucas Leemann (Columbia University), as part of the University of Lausanne's Swiss Electoral Studies (Selects), http://www2.unil.ch/selects%5B%5D, as published in Comparing Candidates and Citizens in the Ideological Space, Swiss Political Science Review 16(3) pp. 499-531(33). The graphical representation of the data is based on a graphic published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung of 30 October 2010, p.13.

- Nationalrat 2007

- Archived 3 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Nationalratswahlen: Kantonale Parteistärke (Kanton = 100%) (Report). Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 29 November 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

| Part of a series on |

| Christian Democracy |

|---|

|

|

Further reading

- Gees, Thomas (2004). Michael Gehler; Wolfram Kaiser (eds.). Successful as a 'Go Between': The Conservative People's Party in Switzerland. Christian Democracy in Europe since 1945. Routledge. pp. 33–46. ISBN 0-7146-5662-3.

- Rölli-Alkemper, Lukas (2004). Wolfram Kaiser; Helmut Wohnout (eds.). Catholics between Emancipation and Integration: The Conservative People's Party in Switzerland. Political Catholicism in Europe 1918-45. Routledge. pp. 53–64. ISBN 0-7146-5650-X.