Switzerland–European Union relations

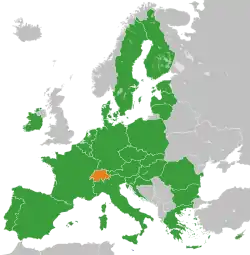

Switzerland is not a member state of the European Union (EU). It is associated with the Union through a series of bilateral treaties in which Switzerland has adopted various provisions of European Union law in order to participate in the Union's single market, without joining as a member state. All but one (the microstate Liechtenstein) of Switzerland's neighbouring countries are EU member states.

| |

EU |

Switzerland |

|---|---|

Comparison

| Population | 447,206,135[1] | 8,570,146 (2019 estimate)[2] |

| Area | 4,324,782 km2 (1,669,808 sq mi)[3] | 41,285 km2 (15,940 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 115/km2 (300/sq mi) | 207/km2 (536.1/sq mi) |

| Capital | Brussels (de facto) | None (de jure), Bern (de facto) |

| Global cities[4] | Paris, Amsterdam, Milan, Frankfurt, Madrid, Brussels, Warsaw, Stockholm, Vienna, Dublin, Luxembourg, Munich, Lisbon, Prague | Zürich |

| Government | Supranational parliamentary democracy based on the European treaties[5] | Federal semi-direct democracy under a multi-party assembly-independent[6][7] directorial republic |

| First Leader | High Authority President Jean Monnet | Jonas Furrer (First president of the confederation) |

| Current Leader | Charles Michel (President of the European Council) Ursula von der Leyen (President of the European Commission) David Sassoli (President of the European Parliament) |

Guy Parmelin (President) Ignazio Cassis (Vice President) Walter Thurnherr (Federal Chancellor) |

| Official languages | 24 official languages, of which 3 considered "procedural" (English, French and German)[8] | German, French, Italian, Romansh |

| Main Religions | 72% Christianity (48% Roman Catholicism, 12% Protestantism,

8% Eastern Orthodoxy, 4% Other Christianity), 23% non-Religious, 3% Other, 2% Islam |

65.5% Christianity (35.8% Roman Catholic, 23.8% Swiss Reformed, 5.9% Other Christian), 26.3% No religion, 5.3% Islam, 1.6% Others, 1.3% Unknown[9] |

| Ethnic groups | Germans (ca. 83 million),[10] French (ca. 67 million),

Italians (ca. 60 million), Spanish (ca. 47 million), Poles (ca. 46 million), Romanians (ca. 16 million), Dutch (ca. 13 million), Greeks (ca. 11 million), Portuguese (ca. 11 million), and others |

|

| GDP (nominal) | $16.477 trillion, $31,801 per capita | $584 billion, $67,557 per capita |

Trade

The European Union is Switzerland's largest trading partner, and Switzerland is the EU's fourth largest trading partner, after the United Kingdom, U.S. and China. Switzerland accounts for 5.2% of the EU's imports; mainly chemicals, medicinal products, machinery, instruments and time pieces. In terms of services, the EU's exports to Switzerland amounted to €67.0 billion in 2008 while imports from Switzerland stood at €47.2 billion.[11]

Treaties

Switzerland signed a free-trade agreement with the then European Economic Community in 1972, which entered into force in 1973.[12]

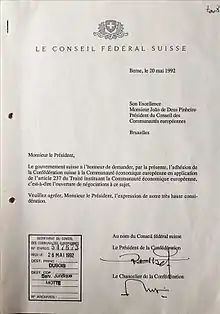

Switzerland is a member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), and took part in negotiating the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement with the European Union. It signed the agreement on 2 May 1992, and submitted an application for accession to the EU on 20 May 1992. However, after a Swiss referendum held on 6 December 1992 rejected EEA membership by 50.3% to 49.7%,[13] the Swiss government decided to suspend negotiations for EU membership until further notice. These did not resume and in 2016, Switzerland formally withdrew its application for EU membership.[14][15]

In 1994, Switzerland and the EU started negotiations about a special relationship outside the EEA. Switzerland wanted to safeguard the economic integration with the EU that the EEA treaty would have permitted, while purging the relationship of the points of contention that had led to the people rejecting the referendum. Swiss politicians stressed the bilateral nature of these negotiations, where negotiations were conducted between two equal partners and not between 16, 26, 28 or 29, as is the case for EU treaty negotiations.

These negotiations resulted in a total of ten treaties, negotiated in two phases, the sum of which makes a large share of EU law applicable to Switzerland. The treaties are:

- Bilateral I agreements (signed 1999, in effect 1 June 2002)

- Free movement of people

- Air traffic

- Road traffic

- Agriculture

- Technical trade barriers

- Public procurement

- Science

- Bilateral II agreements

- Security and asylum and Schengen membership

- Cooperation in fraud pursuits

- Final stipulations in open questions about agriculture, environment, media, education, care of the elderly, statistics and services.

The Bilateral I agreements are expressed to be mutually dependent. If any one of them is denounced or not renewed, they all cease to apply. According to the preamble of the EU decision ratifying the agreements:

The seven agreements are intimately linked to one another by the requirement that they are to come into force at the same time and that they are to cease to apply at the same time, six months after the receipt of a non-renewal or denunciation notice concerning any one of them.[16]

This is referred to as the "guillotine clause". While the bilateral approach theoretically safeguards the right to refuse the application of new EU rules to Switzerland, in practice the scope to do so is limited by the clause. The agreement on the European Economic Area contains a similar clause.

Prior to 2014, the bilateral approach, as it is called in Switzerland, was consistently supported by the Swiss people in referendums. It allows the Swiss to keep a sense of sovereignty, due to arrangements when changes in EU law will only apply after the EU–Swiss Joint Committee decides so in consensus.[17][18] It also limits the EU influence to the ten areas, where the EEA includes more areas, with more exceptions than the EEA has.

From the perspective of the EU, the treaties contain largely the same content as the EEA treaties, making Switzerland a virtual member of the EEA. Most EU law applies universally throughout the EU, the EEA and Switzerland, providing most of the conditions of the free movement of people, goods, services and capital that apply to the member states. Switzerland pays into the EU budget. Switzerland has extended the bilateral treaties to new EU member states; each extension required the approval of Swiss voters in a referendum.

In a referendum on 5 June 2005, Swiss voters agreed, by a 55% majority, to join the Schengen Area. This came into effect on 12 December 2008.[19]

In 2009, the Swiss voted to extend the free movement of people to Bulgaria and Romania by 59.6% in favour to 40.4% against.[20] While the EU Directive 2004/38/EC on the right to move and reside freely does not apply to Switzerland, the Swiss-EU bilateral agreement on the free movement of people contains the same rights both for Swiss and EEA nationals, and their family members.[21]

By 2010, Switzerland had amassed around 210 trade treaties with the EU. Following the institutional changes in the EU–particularly regarding foreign policy and the increased role of the European Parliament–European Council President Herman Van Rompuy and Swiss President Doris Leuthard expressed a desire to "reset" EU-Swiss relations with an easier and cleaner way of applying EU law in Switzerland.[22] In December 2012, the Council of the European Union declared that there will be no further treaties on single market issues unless Switzerland and EU agree on a new legal framework similar to the EEA that, among others, would bind Switzerland more closely to the evolving EU legislation.[23] José Manuel Barroso, the President of the European Commission, later affirmed this position. However, a second referendum on Swiss EEA membership isn't expected,[13] and the Swiss public remains opposed to joining.[24]

Schengen Agreement

In 2009, Switzerland became a participant in the Schengen Area with the acceptance of an association agreement by popular referendum in 2005.[25] This means that there are no passport controls on Switzerland's borders with its neighbours though customs controls continue to apply.

2014 referendum

In a referendum in February 2014, the Swiss voters narrowly approved a proposal to limit the freedom of movement of foreign citizens to Switzerland. The European Commission said it would have to examine the implications of the result on EU–Swiss relations since literal implementation would invoke the guillotine clause.[26]

On 22 December 2016, Switzerland and the EU concluded an agreement whereby a new Swiss law (in response to the referendum) would require Swiss employers to take on any job seekers (whether Swiss nationals or non-Swiss citizens registered in Swiss job agencies) whilst continuing to observe the free movement of EU citizens into Switzerland thus allowing them to work there.[27]

Swiss financial contributions

Since 2008, Switzerland has contributed CHF 1.3 billion towards various projects designed to reduce the economic and social disparities in an enlarged EU.[28] One example of how this money is used is Legionowo railway station, Poland, which is being built with CHF 9.6 million from the Swiss budget.[29]

Proposed framework accord

Negotiations between Switzerland and the European Commission on an institutional framework accord began in 2014 and concluded in November 2018. On 7 December 2018, the Swiss Federal Council decided to neither accept nor decline the negotiated accord, instead opting for a public consultation.[30] The negotiated accord[31] would cover five areas of existing agreements between the EU and Switzerland made in 1999:

- free movement of persons

- air transport

- carriage of goods and passengers by rail and road

- trade in agricultural products

- mutual recognition of standards

Notably, the accord would facilitate EU law in these fields to be readily transposed into Swiss law, and the European Court of Justice would be the final and binding arbiter on disputes in these fields. If the accord were accepted by Switzerland, the country would be in a similar position with regard to imposition of EU law (albeit only in the above five fields) as that in the other EFTA countries which are members of the EEA. Further to matters of sovereignty, specific concerns raised in Switzerland include possible impact on state aid law on the cantonal banks, the potential for transposition of the Citizens’ Rights Directive into Swiss law (and any resulting impact on social welfare for example) and the possible impact on wages enjoyed in the country. Accepting the accord is considered by the Commission to be necessary to allow Swiss access to new fields of the European single market, including the electricity market and stock exchange equivalence.[30]

By June 2019, the Swiss Federal Council found no meaningful compromise neither with the internal consulting partners, such as Swiss labour unions and business representatives, nor with the outgoing EU-commission president Jean-Claude Juncker. EU-member countries have also expressed that no further compromise on the text of the proposed framework accord with Switzerland would be possible. As a result, Brussels did not extend its stock market equivalence to the Swiss stock exchange because of this breakdown of Swiss-EU negotiations, and for a counter-measure, the Swiss Federal Council ordinance from November 2018 was implemented, limiting the future exchange of most EU-traded Swiss stocks to the SIX Swiss Exchange in Zurich.[32][33]

Chronology of the Swiss votes

Chronology of Swiss votes about the European Union:[35][36]

- 3 December 1972: free trade agreement with the European Communities is approved by 72.5% of voters

- 6 December 1992: joining the European Economic Area is rejected by 50.3% of voters. This vote strongly highlighted the cultural divide between the German- and the French-speaking cantons, the Röstigraben. The only German-speaking cantons voting for the EEA were Basel-Stadt and Basel-Landschaft, which border on France and Germany.

- 8 June 1997: the federal popular initiative "negotiations concerning EU membership: let the people decide!" on requiring the approval of a referendum and the Cantons to launch accession negotiations with the EU (« Négociations d'adhésion à l'UE : que le peuple décide ! ») is rejected by 74.1% of voters.

- 21 May 2000: the Bilateral agreements with the EU are accepted by 67.2% of voters.

- 4 March 2001: the federal popular initiative "yes to Europe!" (« Oui à l'Europe ! ») on opening accession negotiations with the EU is rejected by 76.8% of voters.

- 5 June 2005: the Schengen Agreement and the Dublin Regulation are approved by 54.6% of voters.

- 25 September 2005: the extension of the free movement of persons to the ten new members of the European Union is accepted by 56.0% of voters.

- 26 November 2006: a cohesion contribution of one billion for the ten new member states of the European Union (Eastern Europe Cooperation Act) is approved by 53.4% of voters.

- 8 February 2009: the extension of the free movement of persons to new EU members Bulgaria and Romania is approved by 59.61% of voters.

- 17 May 2009: introduction of biometric passports, as required by the Schengen acquis, is approved by 50.15% of voters.

- 17 June 2012: the federal popular initiative "international agreements: let the people speak!" (« Accords internationaux : la parole au peuple ! ») on requiring all international treaties to be approved in a referendum launched by the Campaign for an Independent and Neutral Switzerland is rejected by 75.3% of voters.

- 9 February 2014: the federal popular initiative "against mass immigration", which would limit the free movement of people from EU member states, is accepted by 50.3% of voters.

- 27 September 2020: the popular initiative "For moderate immigration", which would require the government to withdraw from the 1999 Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons and prevent the conclusion of future agreements which grant the free movement of people to foreign nationals, is rejected by 61.7% of voters.

Among these thirteen votes, three are against further integration with the EU or for reversing integration with the EU (6 December 1992, 4 March 2001, and 9 February 2014); the other ten are votes in favour of either deepening or maintaining integration between Switzerland and the European Union.[35]

Proposals for EU membership

Switzerland took part in negotiating the EEA agreement with the EU and signed the agreement on 2 May 1992 and submitted an application for accession to the EU on 20 May 1992. A Swiss referendum held on 6 December 1992 rejected EEA membership. As a consequence, the Swiss Government suspended negotiations for EU accession until further notice. With the ratification of the second round of bilateral treaties, the Swiss Federal Council downgraded their characterisation of a full EU membership of Switzerland from a "strategic goal" to an "option" in 2006. Membership continued to be the objective of the government and was a "long-term aim" of the Federal Council until 2016, when Switzerland's frozen application was withdrawn.[37][38] The motion was passed by the Council of States and then by the Federal Council in June.[39][40][15] In a letter dated 27 July the Federal Council informed the Presidency of the Council of the European Union that it was withdrawing its application.[41]

Concerns about loss of neutrality and sovereignty are the key issues against membership for some citizens. A 2018 survey of public opinion in Switzerland found only 3% considered that joining the EU was a feasible option.[42]

The popular initiative entitled "Yes to Europe!", calling for the opening of immediate negotiations for EU membership, was rejected in a 4 March 2001 referendum by 76.8% and all cantons.[43][44] The Swiss Federal Council, which was in favour of EU membership, had advised the population to vote against this referendum, since the preconditions for the opening of negotiations had not been met.

The Swiss federal government has recently undergone several substantial U-turns in policy, however, concerning specific agreements with the EU on freedom of movement for workers and areas concerning tax evasion have been addressed within the Swiss banking system. This was a result of the first Switzerland–EU summit in May 2004 where nine bilateral agreements were signed. Romano Prodi, former President of the European Commission, said the agreements "moved Switzerland closer to Europe." Joseph Deiss of the Swiss Federal Council said, "We might not be at the very centre of Europe but we're definitely at the heart of Europe". He continued, "We're beginning a new era of relations between our two entities."[45]

The Swiss population agreed to their country's participation in the Schengen Agreement and joined the area in December 2008.[46]

The result of the referendum on extending the freedom of movement of people to Bulgaria and Romania, which joined the EU on 1 January 2007 caused Switzerland to breach its obligations to the EU. The Swiss government declared in September 2009 that bilateral treaties are not solutions and the membership debate has to be examined again[47] while the left-wing Green Party and the Social Democratic Party stated that they would renew their push for EU membership for Switzerland.[48]

In the February 2014 Swiss immigration referendum, a federal popular initiative "against mass immigration", Swiss voters narrowly approved measures limiting the freedom of movement of foreign citizens to Switzerland. The European Commission said it would have to examine the implications of the result on EU–Swiss relations.[26] Due to the refusal of Switzerland to grant Croatia free movement of persons, the EU accepted Switzerland's access to the Erasmus+ student mobility program only as a "partner country", as opposed to a "programme country", and the EU froze negotiations on access to the EU electricity market. On 4 March 2016, Switzerland and the EU signed a treaty that extends the agreement on the free movement of people to Croatia, which led to Switzerland's full readmission into Horizon 2020, a European funding framework for research and development.[49][50] The treaty was ratified by the National Council on 26 April[51] on the condition that a solution be found to an impasse on implementing the 2014 referendum.[52] The treaty was passed in December 2016.[52] This allowed Switzerland to rejoin Horizon 2020 on 1 January 2017.

Foreign policy

In the field of foreign and security policy, Switzerland and the EU have no overarching agreements. But in its Security Report 2000, the Swiss Federal Council announced the importance of contributing to stability and peace beyond Switzerland's borders and of building an international community of common values. Subsequently, Switzerland started to collaborate in projects of EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). Switzerland has contributed staff or material to EU peace keeping and security missions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kosovo, Macedonia and Aceh in Indonesia.

Close cooperation has also been established in the area of international sanctions. As of 2006, Switzerland has adopted five EU sanctions that were instituted outside of the United Nations. Those affected the former Republic of Yugoslavia (1998), Myanmar (2000), Zimbabwe (2002), Uzbekistan (2006) and Belarus (2006).[53]

Use of the euro in Switzerland

The currency of Switzerland is the Swiss franc. Switzerland (with Liechtenstein) is in the unusual position of being surrounded by countries that use the euro. As a result, the euro is de facto accepted in many places, especially near borders and in tourist regions. Swiss Federal Railways accept euros, both at ticket counters and in automatic ticket machines.[54] Also many public phones, vending machines or ticket machines accept euro coins. Many shops and smaller businesses that accept euros take notes only, and give change in Swiss francs, usually at a less favourable exchange rate than banks. Many bank cash machines issue euros at the traded exchange rate as well as Swiss francs.

On 6 September 2011, the Swiss franc effectively became fixed against the euro: the Franc had always floated independently until its currency appreciation became unacceptable during the eurozone debt crisis. The Swiss National Bank set an CHF/EUR peg that involved a minimum exchange rate of 1.20 francs to the euro, with no upper bound in place. The Bank committed to maintaining this exchange rate to ensure stability. The peg was abandoned on 15 January 2015, when renewed upward pressure on the Swiss franc exceeded the Bank's level of tolerance.[55]

Diplomatic relations between Switzerland and EU member states

| Country | Date of first diplomatic relations | Swiss embassy | Reciprocal embassy | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Ages (by 1513) |

Vienna. Honorary consulates: Bregenz, Graz, Innsbruck, Klagenfurt, Linz, Salzburg. |

Bern. Consulate General: Zurich; honorary consulates: Basel, Chur, Geneva, Lausanne, Lugano, Lucerne, St. Gallen. |

Joint organization of Euro 2008, 165 km of common border. | |

| 1838[57] | Brussels. Honorary consulate: Wilrijk (Antwerp).[58] |

Bern. Consulate General: Geneva; honorary consulates: Basel, Lugano, Neuchâtel, St. Gallen, Zurich.[59] |

Swiss Mission to EU and NATO in Brussels.[60] | |

| 1905[Note 1] | Sofia. | Bern. | ||

| 1991[63] | Zagreb. Consulate: Split. |

Bern. Consulates: Zurich, Lugano. |

Switzerland recognized Croatia in early 1992 shortly after it gained independence in 1991. | |

| 1960[Note 2] | Nicosia.[Note 3] | Rome (Italy). Consulates General: Geneva, Zurich. |

||

| 1993.[66] | Prague. | Bern. Honorary consulates: Basel, Zurich, Locarno. |

||

| 1945[68] | Copenhagen.[Note 4] | Bern. | ||

| 1938, 1991[Note 5] | Consulate General of Switzerland in Tallinn | Vienna (Austria). Honorary consulate: Zurich. |

||

| 1926[Note 6] | Helsinki. | Bern. Honorary consulate general: Zurich; honorary consulates: Basel, Geneva, Lausanne, Lugano, Luzern. |

||

| 1430[Note 7] | Paris. Consulates General: Bordeaux, Lyon, Marseille, Strasbourg. |

Bern. Consulates General: Geneva, Zurich. |

573 km of common borders. | |

| 1871 | Berlin. Consulates General: Frankfurt, Munich, Stuttgart. |

Bern. Consulate General: Geneva. |

334 km of common border. | |

| 1830 | Athens. Consulates: Thessaloniki, Corfu, Patras, Rhodes. |

Bern. Consulate General Geneva. Honorary consulates: Zurich, Lugano. |

||

| Budapest. | Bern. Honorary consulates: Geneva, Zurich, 2 in Zug. |

See also Hungarian diaspora.[Note 8] | ||

| 1922 | Dublin. | Bern. Honorary consulate: Zurich. |

||

| 1868[76] | Rome. Consulates General: Genoa, Milan; honorary consulates: Bari, Bergamo, Bologna, Cagliari, Catania, Florence, Naples, Padua, Reggio Calabria, Trieste, Turin, Venice. |

Bern. Consulates General: Basel, Geneva, Lugano, Zurich; consulate: St. Gallen. |

See also Linguistic geography of Switzerland. 740 km of common borders. | |

| 1921, 1991[Note 9] | Riga. | Vienna (Austria). Honorary consulate: Zurich. |

||

| 1921, 1991 | Riga. Consulate General: Vilnius. |

Bern. Honorary consulates: Geneva, Viganello. |

||

| 1938[79] | Luxembourg.[80] | Bern. | ||

| 1937[83] | Honorary Consulate General: Valletta.[Note 10] | Rome (Italy). Honorary consulates: Lugano, Zurich. |

||

| 1917[84] | The Hague. Consulates General: Amsterdam, Rotterdam; honorary consulates: San Nicolaas in Aruba, Willemstad in Curaçao.[85] |

Bern. Consulates General: Geneva, Zurich; honorary consulates: Basel, Porza.[86] |

Before 1917, through London.[68] | |

| Warsaw.[87] | Bern.[88] | |||

| 1855[89] | Lisbon.[90] | Bern. Consulates General: Zurich, Grand-Saconnex Consulates: Lugano, Sion[91] |

||

| 1911, 1962[Note 11] | Bucharest. | Bern. | ||

| 1993 | Bratislava. | Bern. Honorary consulate: Zurich. |

||

| 1992[94] | Ljubljana.[Note 12] | Bern. | Switzerland recognized Slovenia in early 1992 shortly after it gained independence in 1991. | |

| Middle Ages[95] (by 1513) |

Madrid[96] | Bern[97] | ||

| 1887[98] | Stockholm.[99] | Bern Consulates General: Basel, Lausanne. Consulates: Geneva, Lugano, Zurich.[100] |

See also

Notes

- Switzerland officially recognized Bulgaria on 28 November 1879.

- Year of proclamation of Republic of Cyprus.

- Switzerland had a consular agency in Cyprus since 1937. In 1983 this became a Consulate General and in 1990 an embassy.

- Before 1945: Swiss Legation in Stockholm (Sweden); 1945–1957: Swiss Legation in Copenhagen.

- Switzerland recognised Estonia on 22 April 1922, and diplomatic relations started in 1938. Switzerland never recognised the annexation of Estonia by the Soviet Union and re-recognised Estonia on 28 August 1991. Diplomatic relations were restored on 4 September 1991.

- Switzerland acknowledged Finland on 11 January 1918. Diplomatic relations between them were established on 29 January 1926.

- Permanent since 1522.

- There are between 20,000 and 25,000 Hungarians who live in Switzerland; most of them came after the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

- Switzerland recognised the Latvian state on 23 April 1921. Switzerland never recognised the incorporation of Latvia into the USSR. Both countries renewed their diplomatic relations on 4 September 1991.

- Honorary consulate since 1937; upgraded 2003.

- Legacies since 1911. Embassies since 24 December 1962.

- Since 2001.

References

- "Population on 1 January". Eurostat. European Commission. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- "Bevölkerungsbestand am Ende des 2. Quartal 2019" [Recent monthly and quarterly figures: provisional data] (XLS) (official statistics) (in German, French, and Italian). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO), Swiss Confederation. 19 September 2019. 1155-1500. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- "Field Listing – Area". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Cities ranked "alpha" in 2020 by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network. https://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2020t.html

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved 2015-01-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Shugart, Matthew Søberg (December 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns". French Politics. 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. S2CID 73642272.

- Elgie, Robert (2016). "Government Systems, Party Politics, and Institutional Engineering in the Round". Insight Turkey. 18 (4): 79–92. ISSN 1302-177X. JSTOR 26300453.

- "European Commission - PRESS RELEASES - Press release - Frequently asked questions on languages in Europe". europa.eu. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- "Religions" (official statistics). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Federal Statistical Office FSO. 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Population by sex and citizenship". Federal Statistical Office. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- "Switzerland - Trade - European Commission". Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "Summary of Treaty". Treaties office database.

- Miserez, Marc-Andre (2 December 2012). "Switzerland poised to keep EU at arm's length". swissinfo. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "EU membership application not to be withdrawn". swissinfo. 26 October 2005. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- Schreckinger, Ben. "Switzerland withdraws application to join the EU – POLITICO". Politico.eu. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Decision of the Council, and of the Commission as regards the Agreement on Scientific and Technological Cooperation, of 4 April 2002 on the conclusion of seven Agreements with the Swiss Confederation (2002/309/EC, Euratom) OJ L 114, 30.4.2002, p. 1.

- "EUR-Lex - 22011D0702 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu.

- "EUR-Lex - 22012D0195 - EN - EUR-Lex".

- "Entry to Switzerland". Swiss Federal Office for Migration. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- "Schweiz, 8. Februar 2009 : Weiterführung des Freizügigkeitsabkommens zwischen der Schweiz und der Europäischen Gemeinschaft und Ausdehnung auf Bulgarien und Rumänien" (in German). Database and Search Engine for Direct Democracy. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Agreement with the Swiss Federation: free movement of persons". European Commission. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- Pop, Valentina (19 July 2010) EU looking to reset relations with Switzerland, EU Observer

- Council of the European Union, 8 Jan 2013: Council conclusions on EU relations with EFTA countries

- Keiser, Andreas (30 November 2012). "Swiss still prefer bilateral accords with EU". Swissinfo. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Allen M. (March 2009). Switzerland's Schengen entry finally complete. swissinfo.ch; retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Swiss immigration: 50.3% back quotas, final results show". BBC. 9 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- EU and Switzerland agree on free movement – euobserver, 22 Dec 2016

- "The Swiss contribution in brief". www.dfae.admin.ch.

- Transport Center in Legionowo - Switzerland's Contribution to the Enlarged EU - Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, retrieved 12 July 2016

- Swissinfo 7 December 2018

- Swiss Confederation ACCORD FACILITANT LES RELATIONS BILATÉRALES... 23.11.2018

- "EU equivalence assessment of Swiss stock exchanges". ILO.com. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Brüssel soll warten – die Schweiz schiebt den Rahmenvertrag auf die lange Bank (in German). Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Switzerland referendum on the Agreement on the European Economic Area (EEA)". European Election Database.

- "Ce qui nous lie à l'Union européenne", Le Temps, Friday 4 April 2014.

- "Switzerland and the European Union" (PDF) (2nd ed.). Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Swiss Lawmakers Vote to Pull Forgotten EU Application". The Local. 2 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Alexe, Dan (2 March 2016). "Switzerland Withdraws Its Old, Outdated EU Application". New Europe. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Swiss to Withdraw Dormant EU Bid". Swissinfo. 15 June 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- "Switzerland withdraws its application for EU membership". Lenews.ch. 6 December 1992. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "Retrait de la demande d'adhesion de la Suisse a l'UE" (PDF). Swiss Federal Council. 27 July 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- Webwire Credit Suisse Europe Barometer (13 November 2018)

- "Swiss say 'no' to EU". BBC News. 4 March 2001. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- "Votation populaire du 4 mars 2001". Federal Chancellery. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- "Europa.admin.ch". Europa.admin.ch. 14 December 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- "Entry to Switzerland". Swiss Federal Office for Migration. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- "Bundesrat verweist auf Grenzen des bilateralen Wegs", Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German), 23 September 2009.

- "Linke lanciert neue EU-Beitrittsdebatte" (in German). baz.online. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- Franklin, Joshua (4 March 2016). "Swiss, EU Agree to Extend Free Movement Deal to Workers From Croatia". Reuters. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Geiser, Urs (4 March 2016). "Swiss Announce Unilateral Safeguard Clause to Curb Immigration". Swissinfo. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "Swiss Lawmakers Back Croatia Free Movement Treaty". Swissinfo. 26 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "Swiss Extend Free Movement to Croatia After Immigration Vote". Swissinfo. 16 December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- Itten, Anatol (2010): Foreign Policy Cooperation between the EU and Switzerland: Notice of the wind of changes. Saarbrücken: VDM-Verlag.

- "SBB ticket machines accept euros". SBB. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- "Swiss franc soars as Switzerland abandons euro cap". BBC News. 15 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Austria references:

- Austrian Foreign Ministry: list of bilateral treaties with the United Kingdom (in German only)

- Austrian embassy in Bern (in German only)

- Austrian mission in Geneva

- Austrian consulate in Zurich (in German only)

- Honorary Consulate in St; Gallen

- Swiss Department of Foreign Affairs about the relation with Austria

- Swiss Department of Foreign Affairs: list of Swiss representation in Austria

- Swiss embassy in Vienna (in German only)

- "Relations bilatérales". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Représentations suisses". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Représentations en Suisse". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Représentations suisses". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- Bulgaria references:

- Croatia references:

- "MVEP • Date of Recognition and Establishment of Diplomatic Relations". Mvep.hr. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- Cyprus references:

- Czech Republic references:

- "Relations bilatérales". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- Denmark references:

- "Relations bilatérales". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- Estonia references:

- Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs about relations with Switzerland

- Estonian embassy in Vienna (also accredited to Switzerland): about bilateral relations

- Estonian honorary consulate in Zurich (in German only)

- Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs about relations with Estonia

- Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs: Swiss representation in Estonia

- Finland references:

- France references:

- Germany references:

- Hungary references:

- Ireland references:

- Italy references:

- Italian embassy in Bern (in Italian only)

- Italian Consulates General in Basel (in French, German and Italian only)

- Italian Consulates General in Geneva (in French and Italian only)

- Italian Consulates General in Lugano (in Italian only)

- Italian Consulates General in Zurich (in German and Italian only)

- Italian Consulates General in St. Gallen (in German and Italian only)

- Swiss Department of Foreign Affairs about the relations with Italy

- Swiss embassy in Rome (in Italian only)

- Swiss Consulates General in Genoa (in Italian only)

- Swiss Consulates General in Milan (in Italian only)

- "Relations bilatérales". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- Latvia references:

- Lithuania references:

- "Relations bilatérales". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Représentation suisse". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Représentations en Suisse". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- Malta references:

- "Relations bilatérales". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 February 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Error". www.eda.admin.ch. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009.

- "Error". www.eda.admin.ch. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007.

- "Swiss embassy in Warsaw". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Polish embassy in Bern". Berno.polemb.net. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Relations bilatérales". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Représentations suisses". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Représentations en Suisse". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- Slovakia references:

- Slovenia references:

- "Relations bilatérales". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- Relations bilatérales Suisse–Espagne (in Spanish)

- Embajada de Suiza en España (in Spanish)

- Consulado General de Suiza en Barcelona (in Spanish)

- "Relations bilatérales Suisse–Suède". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Représentation suisse en Suède". Eda.admin.ch. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Sweden Abroad". Swedenabroad.com. Retrieved 17 January 2015.