Climate change in South Africa

Climate change has highly impacted South Africa, primarily due to increased temperatures and rainfall variability. Evidence shows that extreme weather events are becoming more prominent due to climate change. [2] This is a critical concern for South Africans as climate change will affect the overall status and wellbeing of the country, for example with regards to water resources. Just like many other parts of the world, climate research showed that the real challenge in South Africa was more related to environmental issues more than developmental ones.[3] The most severe effect will be targeting the water supply, which has huge effects on the agriculture sector.[4] Speedy environmental changes are resulting clear effects on the community and environmental level in different ways and aspects, starting with air quality, to temperature and weather patterns, reaching out to food security and disease burden.[5]

The various effects of climate change on rural communities are expected to include: drought, depletion of water resources and biodiversity, soil erosion, decreased subsistence economies and cessation of cultural activities.[6]

Africa is currently and prospectively suffering from significant heat waves based on the nature of the continent amid the current environmental crisis.[7] South Africa contributes considerable CO2 emissions, being the 14th largest emitter of CO2.[4] Above the global average, South Africa had 9.5 tons of CO2 emissions per capita in 2015.[4] This is in large part due to its energy system relying heavily on coal and oil.[4] As part of its international commitments, South Africa has pledged to peak emissions between 2020 and 2025.[4]

Impacts

There has been different confirmations over climate change effects in South Africa with a rapid decrease in rain fall and noticed high temperature levels along side with flooding disaster in the northern Algeria. This caused around 800 deaths and economic loss of about $400 million, a massive drought in East Africa region which was known to be the worst for ages.[8] Climate change has direct effects on the overall wellbeing and health. These start with the capacity to gain nutrition from land and oceans, to the growth and irritation on the level of infections and various viruses[6] According to the Second Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change, climate change is the top concern for health organizations on the global level in the 21st century.[9] The Climate and Health Alliance 2012 Climate Vulnerability Monitor predicts that the price that we are going to pay once we fail in taking considerable actions in Climate Change issues will exceed 400,000 related mortalities each year, increasing to 700,000 by 2030, and will cost US$1.2 trillion.[10]

Coming to South Africa status with respect to Climate Change it is extremely critical on the level governmental ability to reduce the increasing levels of illnesses.[11] Climate change is expected to raise temperatures in South Africa by 2-3C by mid-century, and 3-4C by the end of the century in an intermediate scenario.[4] Impacts will also include changing rain patterns and increased evaporation, increasing the likelihood of extreme droughts.[4] Popular awareness of these potential impacts increased with the 2018–20 Southern Africa drought and subsequent Cape Town water crisis.[12]

In South Africa, an unfair spreading of healthcare luxuries is clear to notice. Mainly the underprivileged groups have only to only 12% of the nation’s medical professionals.[6]

Agriculture

The main challenge that faces any nation because of climate change is its direct effect on food security. In this sense, Africa is listed as the most vulnerable continent to climate changes.[13] In Ethiopia for example, food production faces a lot of challenges because of climate change. It is noted that there is an increase in the annual production losses to climate changes from year to year.[12]

Agriculture is expected to be negatively impacted by droughts, reduced rainfall, pests, and other changes in the environment due to climate change.[4] Higher temperatures in South Africa[14] and less rainfall will result in limited water resources and changing soil moisture, leading to decreased cropland productivity.[15]

Some predictions show surface water supply could decrease by 60% by the year 2070 in parts of the Western Cape.[16] To reverse the damage caused by land mismanagement, the government has supported a scheme which promotes sustainable development and the use of natural resources.[17]

Maize production, which contributes to a 36% majority of the gross value of South Africa's field crops, has also experienced negative effects due to climate change. The estimated value of the loss, which takes into consideration scenarios with and without the carbon dioxide fertilization effect,[18] ranges between tens and hundreds of millions of lands.[19]

Tourism

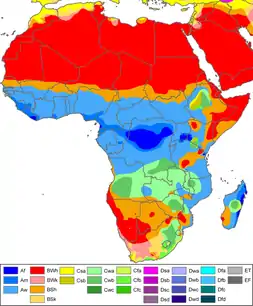

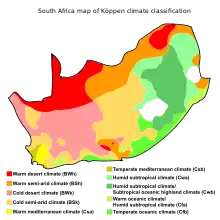

South Africa has an important tourism aspect to look at and give considerable attention to when considering climate change impact. This is a sensitive sector to mention but its importance lies in its vulnerability to climate change that is growing lately.[20] Challenges exceed the fact that there is a need to pave the way for more tourists to come. South Africa's main concern extends to develop poverty mitigation plans resulted from climate change in South Africa.[21] Tourism urged policy makers in Africa to improve job opportunities, economical growth and support different industries. There are different critical challenges facing Tourism sector in South Africa and that was mainly a result of Climate Change effects.[8] In this regard, it is important to notice that the national government in South Africa started to implement new tourism and climate based policies to over come the challenges. [22] It is significant to mention that the general climate in South Africa suffers from varied conditions and changes/ These variations target summer and winter rainfall regions, subtropical areas, and both humid and arid regions. [23]

Greenhouse gas emissions

Like all countries which are party to the Paris Agreement South Africa will report its greenhouse gas inventory to the UNFCCC at least biennially from 2024 at the latest.[24]

Energy sector

South Africa has a large energy sector, being the second-largest economy in Africa.

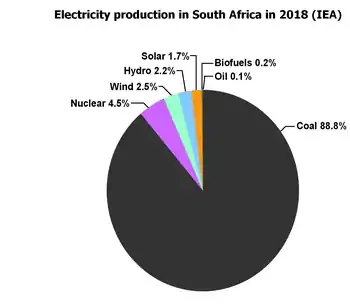

The country consumed 227 TWh of electricity in 2018.[25] The vast majority of South Africa's electricity was produced from coal, with the fuel responsible for 88% of production in 2017.[26] South Africa is the 7th largest coal producer in the world.[26] As of July 2018, South Africa had a coal power generation capacity of 39 gigawatts (GW).[26]

South Africa is planning to shift away from coal in the electricity sector. The country aims to decommission 34 GW of coal-fired power capacity by 2050.[26] It also aims to build at least 20 GW of renewable power generation capacity by 2030.[27]

South Africa is the world's 14th largest emitter of greenhouse gases.[26]

South Africa aims to generate 77,834 megawatts (MW) of electricity by 2030, with new capacity coming significantly from renewable sources to meet emission reduction targets.[28]Renewable energy

Renewable energy in South Africa is energy generated in South Africa from renewable resources, those that naturally replenish themselves—such as sunlight, wind, tides, waves, rain, biomass, and geothermal heat.[29] Renewable energy focuses on four core areas: electricity generation, air and water heating/cooling, transportation, and rural energy services.[30] The energy sector in South Africa is an important component of global energy regimes due to the country's innovation and advances in renewable energy.[31] South Africa's contribution to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is ranked as moderate and its per capita emission rate is higher than the global average. Energy demand within the country is expected to rise steadily and double by 2025.[31]

Of all South African renewable energy sources, solar holds the most potential.[31] Because of the country's geographic location, it receives large amounts of solar energy.[31] Wind energy is also a major potential source of renewable energy.[32] Due to the high wind velocity on the coast of the country, Cape Town has implemented multiple wind farms, which generate significant amounts of energy.[32] Renewable energy systems in the long-term are comparable or cost slightly less than non-renewable sources. Biomass is currently the largest renewable energy contributor in South Africa with 9-14% of the total energy mix.[33] Renewable energy systems are costly to implement in the beginning but provide high economic returns in the long-run.[34]

The two main barriers accompanying renewable energy in South Africa are: the energy innovation system, and the high cost of renewable energy technologies.[31] The Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Procurement Programme (REI4P) suggests that the cost associated with renewable energy will equal the cost of non-renewable energy by 2030.[34] Renewable energy is becoming more efficient, inexpensive, and widely used.[29] South Africa has an abundance of renewable resources that can effectively supply the country's energy.[33]Transportation

.jpg.webp)

The transport sector in South Africa contributes 10.8% of total Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions in the country. Apart from the direct emissions, indirect emissions through the production and transportation of fuels also provide substantial emissions.[35][4] Road transport, in particular, contributes approximately three quarters to total transport emissions.[36]

Political action

The South African government drafted its National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (NCCAS) in 2019. This strategy presents a vision for adapting to climate change and increasing resilience in the country. This strategy also and outlines priority areas for achieving this vision, which includes water resources, agriculture and commercial forestry, health, biodiversity and ecosystems, human settlements, and disaster risk reduction.[2] This strategy was also developed to act on the country's commitment to its obligations in the Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The South African government has committed to a peak of CO2 emissions between 2020 and 2025. South Africa has agreed to working with other signatories of the Paris Agreement to keep temperature increases below 2 °C.[37] However, independent observers have called the current actions by the government insufficient.[4] In part, this failure to act is related to the government ownership of Eskom, which is responsible for much of the coal operation in the country.[4] Similarly, the economy is one of the most energy-intensive in the world although it has not been setting mitigation targets for industry.[4] Catalysing finance and investment to transition to a low carbon economy and society is a major challenge for South Africa.[37]

Public health

Although research is limited to climate change and health in South Africa, there is evidence that climate change will have negative impacts on public health, especially due to the high proportion of vulnerable people.[38] There is already a high burden of disease in South Africa linked to environmental stressors and climate change will exacerbate many of these social and environmental issues.[39] Climate change is projected to threaten public health through increased heat stress, rises in vector-borne diseases and infectious diseases, worsening extreme weather events, a decline in food security, and increased mental health stress.[40] A 2019 survey of literature on adaptation and public health, found that "the volume and quality of research is disappointing, and disproportionate to the threat posed by climate change in South Africa.".[41]

Taking into consideration, Malaria, it is vital to consider discussing it since it is an important concern of morbidity and mortality on sub-Saharan Africa.[42] Temperature has unstable effects on vector-borne disease transmission.[43] In a study conducted on Climate Change and its burdens over the health sector in South Africa in 2019 within 4 areas in Kenya, huge effects were noticed. It showed a unimodal relationship between blood smear positivity for malaria and environmental temperature that peaked at 25°C.This shows the severe effect of temperature rise with respect to health crisis resulting.[44]

References

- Kottek, Markus; Grieser, Jürgen; Beck, Christoph; Rudolf, Bruno; Rubel, Franz (2006-07-10). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". Meteorologische Zeitschrift. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. ISSN 0941-2948.

- Republic of South Africa, National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (NCCAS), Version UE10, 13 November 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/nationalclimatechange_adaptationstrategy_ue10november2019.pdf

- "Impacts of and Adaptation to Climate Change", Climate Change and Technological Options, Vienna: Springer Vienna, pp. 51–58, 2008, doi:10.1007/978-3-211-78203-3_5, ISBN 978-3-211-78202-6, retrieved 2020-11-24

- "The Carbon Brief Profile: South Africa". Carbon Brief. 2018-10-15. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- "International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health". www.mdpi.com. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- "Sustainability". www.mdpi.com. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- Parkes, Ben; Cronin, Jennifer; Dessens, Olivier; Sultan, Benjamin (2019-06-01). "Climate change in Africa: costs of mitigating heat stress". Climatic Change. 154 (3): 461–476. Bibcode:2019ClCh..154..461P. doi:10.1007/s10584-019-02405-w. ISSN 1573-1480. S2CID 159436152.

- "GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites". gtg.webhost.uoradea.ro. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- Watts, Nick; Adger, W. Neil; Agnolucci, Paolo; Blackstock, Jason; Byass, Peter; Cai, Wenjia; Chaytor, Sarah; Colbourn, Tim; Collins, Mat; Cooper, Adam; Cox, Peter M. (2015-11-07). "Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health". The Lancet. 386 (10006): 1861–1914. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60854-6. hdl:10871/17695. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 26111439. S2CID 205979317.

- "Climate Vulnerability Monitor - 2nd Edition - 2012 - CVF DARA". CVF. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- unesdoc.unesco.org https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000223388. Retrieved 2020-11-26. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Likelihood of Cape Town water crisis tripled by climate change – World Weather Attribution". Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- "CAADP to reduce food security emergencies in Africa - World". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- "The best time to go to South Africa's Cape | weather & climate | Expert Africa". www.expertafrica.com. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- Calzadilla, Alvaro; Zhu, Tingju; Rehdanz, Katrin; Tol, Richard S. J.; Ringler, Claudia (2014-05-01). "Climate change and agriculture: Impacts and adaptation options in South Africa". Water Resources and Economics. 5: 24–48. doi:10.1016/j.wre.2014.03.001. ISSN 2212-4284.

- Climate change to create African 'water refugees' – scientists, Reuters Alertnet. Accessed 21 September 2006]. Archived 25 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Department of Agriculture South Africa". Nda.agric.za. Archived from the original on 11 November 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- "The CO2 fertilization effect: higher carbohydrate production and retention as biomass and seed yield". Fao.org. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- J. Turpie; et al. (2002). "Economic Impacts of Climate Change in South Africa: A Preliminary Analysis of Unmitigated Damage Costs" (PDF). Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies Inc. Southern Waters Ecological Research & Consulting & Energy & Development Research Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009.

- Fitchett, Jennifer M.; Grant, Bronwyn; Hoogendoorn, Gijsbert (June 2016). "Climate change threats to two low-lying South African coastal towns: Risks and perceptions". South African Journal of Science. 112 (5–6): 1–9. doi:10.17159/sajs.2016/20150262. ISSN 0038-2353.

- Mugambiwa, Shingirai S.; Tirivangasi, Happy M. (2017). "Climate change: A threat towards achieving 'Sustainable Development Goal number two' (end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture) in South Africa". Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies. 9 (1): 350. doi:10.4102/jamba.v9i1.350. ISSN 1996-1421. PMC 6014178. PMID 29955332.

- "Tourism and Climate Change: Stakeholder Perceptions of At Risk Tourism Segments in South Africa". Euro Economica. 37 (2): 104–118. 2018. ISSN 1582-8859.

- Fitchett, Jennifer M.; Robinson, Dean; Hoogendoorn, Gijsbert (2017-06-03). "Climate suitability for tourism in South Africa". Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 25 (6): 851–867. doi:10.1080/09669582.2016.1251933. ISSN 0966-9582. S2CID 157349642.

- "NDC reporting: making the Paris Agreement Transparency Framework work". Energy Post. 2019-07-19.

- "South Africa - Countries & Regions". IEA. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- "The Carbon Brief Profile: South Africa". Carbon Brief. 2018-10-15. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- "South Africa Energy Outlook – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- "Renewables in, coal out: South Africa's energy forecast". Renewable Energy World. 2019-10-18. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- Ellabban, Omar; Abu-Rub, Haitham; Blaabjerg, Frede (2014-11-01). "Renewable energy resources: Current status, future prospects and their enabling technology". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 39: 748–764. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.113.

- "Renewables 2010 Global Status Report" (PDF). www.ren21.net. September 24, 2010. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Pegels, Anna (2010). "Renewable Energy in South Africa: Potentials, Barriers, and options for support". Energy Policy. 38 (9): 4945–4954. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.03.077.

- Winkler, Harald (2005). "Renewable energy policy in South Africa: policy options for renewable electricity". Energy Policy. 33: 27–38. doi:10.1016/S0301-4215(03)00195-2.

- Banks, Douglas; Schäffler, Jason (2006). "The potential contribution of renewable energy in South Africa". Sustainable Energy & Climate Change Project: 1–116.

- Walwyn, David; Brent, Alan (2015). "Renewable energy gathers steam in South Africa" (PDF). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 41: 390–401. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.08.049. hdl:2263/49731.

- Green Transport Strategy for South Africa: (2018-2050), 2018. Accessed from: https://www.transport.gov.za/documents/11623/89294/Green_Transport_Strategy_2018_2050_onlineversion.pdf/71e19f1d-259e-4c55-9b27-30db418f105a

- Tongwane, Mphethe; Piketh, Stuart; Stevens, Luanne; Ramotubei, Teke (2015-06-01). "Greenhouse gas emissions from road transport in South Africa and Lesotho between 2000 and 2009". Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 37: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2015.02.017. ISSN 1361-9209.

- UNFCCC, South Africa’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), 2015, Accessed: https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/PublishedDocuments/South%20Africa%20First/South%20Africa.pdf

- Chersich, Matthew F.; Wright, Caradee Y.; Venter, Francois; Rees, Helen; Scorgie, Fiona; Erasmus, Barend (September 2018). "Impacts of Climate Change on Health and Wellbeing in South Africa". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15 (9): 1884. doi:10.3390/ijerph15091884. ISSN 1661-7827. PMC 6164733. PMID 30200277.

- Mugambiwa, Shingirai S.; Tirivangasi, Happy M. (2017-02-27). "Climate change: A threat towards achieving 'Sustainable Development Goal number two' (end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture) in South Africa". Jàmbá : Journal of Disaster Risk Studies. 9 (1): 350. doi:10.4102/jamba.v9i1.350. ISSN 2072-845X. PMC 6014178. PMID 29955332.

- Wright, C. Y.; Garland, R. M.; Norval, M.; Vogel, C. (August 2014). "Human health impacts in a changing South African climate". South African Medical Journal. 104 (8): 579–582. doi:10.7196/samj.8603. ISSN 0256-9574. PMID 26307804.

- Chersich, Matthew F.; Wright, Caradee Y. (2019-03-19). "Climate change adaptation in South Africa: a case study on the role of the health sector". Globalization and Health. 15 (1): 22. doi:10.1186/s12992-019-0466-x. ISSN 1744-8603. PMC 6423888. PMID 30890178.

- Bhatt, S.; Weiss, D.J.; Cameron, E.; Bisanzio, D.; Mappin, B.; Dalrymple, U.; Battle, K.; Moyes, C.L.; Henry, A.; Eckhoff, P.A.; Wenger, E.A. (2015-10-08). "The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015". Nature. 526 (7572): 207–211. Bibcode:2015Natur.526..207B. doi:10.1038/nature15535. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 4820050. PMID 26375008.

- Mordecai, Erin A.; Ryan, Sadie J.; Caldwell, Jamie M.; Shah, Melisa M.; Labeaud, A Desiree (2020-09-01). "Climate change could shift disease burden from malaria to arboviruses in Africa". The Lancet Planetary Health. 4 (9): e416–e423. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30178-9. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 7490804. PMID 32918887.

- "The Lancet Planetary Health". www.thelancet.com. Retrieved 2020-11-29.