Cochabamba

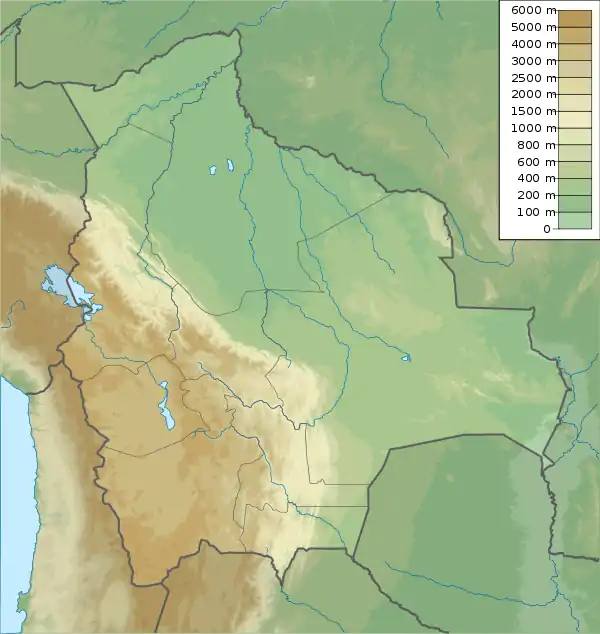

Cochabamba (Aymara: Quchapampa; Quechua: Quchapanpa) is a city and municipality in central Bolivia in a valley in the Andes mountain range. It is the capital of the Cochabamba Department and the fourth largest city in Bolivia, with a population of 630,587 according to the 2012 Bolivian census.[1] Its name is from a compound of the Quechua words qucha "lake" and pampa, "open plain."[2] Residents of the city and the surrounding areas are commonly referred to as cochalas or, more formally, cochabambinos.

Cochabamba

Qhuchapampa | |

|---|---|

City & Municipality | |

CBB | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nicknames: "City of Eternal Spring" "The Garden City" "La Llajta" | |

Cochabamba Location in Bolivia  Cochabamba Cochabamba (South America) | |

| Coordinates: 17°23′S 66°10′W | |

| Country | |

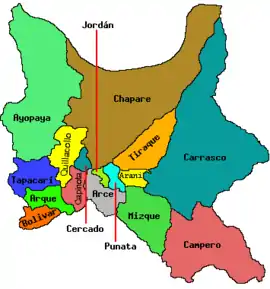

| Department | Cochabamba |

| Province | Cercado Province |

| Municipality | Cochabamba Municipality |

| Founded | August 15, 1571 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Autonomous Government |

| • Mayor | José María Leyes |

| Area | |

| • City & Municipality | 170 km2 (70 sq mi) |

| • Land | 169 km2 (65 sq mi) |

| • Water | 1 km2 (0.4 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 111 km2 (43 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,558 m (8,392 ft) |

| Population (2012 Census)[1] | |

| • Urban | 630,587 |

| • Metro | 1,370,104 |

| Demonym(s) | Cochabambino |

| Climate | BSk |

| Website | Official website |

It is known as the "City of Eternal Spring" or "The Garden City" because of its spring-like temperatures all year round. It is also known as "La Llajta," which means "town" in Quechua.

History

Pre-Inca and Inca

The Cochabamba valley has been inhabited for thousands of years due to its fertile productive soils and mild climate. Archaeological evidence suggests that the initial inhabitants were of indigenous ethnic groups: Tiwanaku, Tupuraya, Mojocoya, Omereque, and Inca inhabited the valley at times before the Spanish arrived.[3]

The area got its name, from Quechua Kochaj-pampa, as part of the Inca civilization. The area was conquered by Topa Inca Yupanqui (ruled 1471-1493). His son Huayna Capac turned Cochabamba into a large production enclave or state farm to serve the Incas. Possibly depopulated during the conquest, Huayna Capac imported 14,000 people, called mitimas, to work the land. The principal crop was maize which could not be grown in much of the high and cold heartland of the Inca Empire. The maize was stored in 2,400 storehouses (qollqas) in the hills overlooking the valley or transported by llama caravan to storage sites in Paria, Cusco, of other Inca administrative centers. Most of the maize was probably used to sustain the Inca army during its campaigns.[4]

Spanish and Bolivian

The first Spanish inhabitant of the valley was Garci Ruiz de Orellana in 1542. He purchased the majority of the land from local tribal chiefs Achata and Consavana through a title registered in 1552 at the Imperial City of Potosí. The price paid was 130 pesos. His residence, known as the House of Mayorazgo, stands in the Cala Cala neighborhood.

The city, called Villa de Oropesa, was founded on 2 August 1571 by order of Viceroy Francisco de Toledo, Count of Oropesa. It was to be an agricultural production centre to provide food and wood[5] for the mining towns of the relatively nearby Altiplano region, particularly Potosí which became one of the largest and richest cities in the world during the 16th and 17th centuries — funding the vast wealth that ultimately made Spain a world power. In fact, Anthropologist Jack Weatherford and others have cited the city of Potosí as the birth of capitalism because of the money it and materialism it provided Spain.[6] Thus, with the silver mining industry in Potosí at its height, Cochabamba thrived during its first centuries. However, the city entered a period of decline during the 18th century as mining began to wane.

In 1786, King Charles III of Spain renamed the city to the 'loyal and valiant' Villa of Cochabamba. This was done to commend the city's pivotal role in suppressing the indigenous rebellions of 1781 in Oruro by sending armed forces to Oruro to quell the uprisings. Since the late 19th century it has again been generally successful as an agricultural centre for Bolivia.

The 1793 census shows that the city had a population of 22,305 persons. There were 12,980 mestizos, 6,368 Spaniards, 1,182 indigenous natives, 1,600 mulattos and 175 African slaves.

In 1812, Cochabamba was the site of a riot against the Spanish Army. On May 27, thousands of women took up arms against the Spanish. According to historian Nathaniel Aguirre: "From Cochabamba, many men have fled. Not one woman. On the hillside, a great clamor. Cochabamba's plebeian women, at bay, fight from the center of a circle of fire. Surrounded by five thousand Spaniards, they resist with battered tin guns and a few arquebuses; and they fight to the last yell, whose echoes will resound throughout the long war for independence. Whenever his army weakens, General Manuel Belgrano will shout those words which never fail to restore courage and spark anger. The general will ask his vacillating soldiers: 'Are the women of Cochabamba present?"[7]

To celebrate their bravery, Bolivia now marks May 27 as Mother's Day.[8]

In 1900, the population was 21,886.

Besides a number of schools and charitable institutions, the Catholic diocese has 55 parishes, 80 churches and chapels, and 160 priests.

In 1998, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreed to give Bolivia a loan of $138 million to control inflation and promote economic growth. However, it only agreed to do so on the condition that Bolivia sell "all remaining public enterprises," including its national oil refineries and the local water company, SEMAPA.[9] In 1999, a group of private investors, specifically the Bechtel Corporation with headquarters in San Francisco, California, United States of America, came together under the name of Aguas del Tunari and bought the rights for the privatization of the city's water.[10] In that same year, the World Bank (WB) refused to subsidize the water to help lower the cost for the people. Then in 2000, the people of Cochabamba began to protest as water priced hiked to a 50% increase that the majority could not afford.[11] The Coalition for the Defense of Water and Life, and its leader Oscar Olivera, started a demonstration in La Plaza 14 de Septiembre also known as La Plaza Principal. The march was meant to be peaceful, but after two days the police used tear gas against the protestors and injured about 175 people and killed 1 and blinded two. Soon after, news reports were made about the protests and the violence.[9] The Defense of Water and Life held an unofficial referendum and 96% of 50,000 people want Aguas del Tunari's contract to terminate, but the government refused. The protests only grew and the entire world began to watch forcing Bechtel to leave its contract and return SEMAPA to the public. Bechtel as well tried to sue the Bolivian government for $50 million but it withdrew its claim shortly after.[11] This event was soon labeled as the Water Wars and became a driving force for anti-globalization projects such as the UN's decision to make water sanitation a human right and privatization of water as unethical in 2010. Additionally, the Water Wars would help spark the next revolt against the privatization of natural gases in 2003 to 2005 that would lead to the removal of two presidents, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada and Carlos Mesa, and the rise of President Evo Morales in 2006.[12]

In January 2007, city dwellers clashed with mostly rural protestors, leaving four dead and over 130 injured. The first democratically elected Prefect of Cochabamba, Manfred Reyes Villa, had allied himself with the leaders of Bolivia's Eastern Departments in a dispute with President Evo Morales over regional autonomy and other political issues. The protestors blockaded the highways, bridges, and main roads, having days earlier set fire to the departmental seat of government, trying to force the resignation of Reyes Villa. Citizens attacked the protestors, breaking the blockade and routing them, while the police did little to stop the violence. Further attempts by the protestors to reinstate the blockade and threaten the government were unsuccessful, but the underlying tensions had not been resolved.

In July 2007, a monument erected by veterans of January's protest movement in honor of those killed and injured by government supporters, was destroyed in the middle of the night, reigniting racial conflicts in the city.

In August 2008, a nationwide referendum was held. The prefect of Cochabamba, Manfred Reyes Villa, was not confirmed by the voters of the department. The mayor of Cochabamba in 2018 is José María Leyes.

Climate

Cochabamba is known for its "Eternal Spring". Neither experiencing the humid heat of Santa Cruz nor the frigid winds of La Paz, Cochabamba experiences a semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSk). The characteristic of the climate is an extended dry season that runs from May until October with a wet season that generally begins in November with the principal rains ending in March.

| Climate data for Cochabamba | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.0 (95.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.6 (87.1) |

32.8 (91.0) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.8 (91.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 23.9 (75.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.6) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.5 (63.5) |

16.4 (61.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

1.7 (35.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 94.0 (3.70) |

68.8 (2.71) |

38.4 (1.51) |

12.7 (0.50) |

2.3 (0.09) |

1.3 (0.05) |

2.5 (0.10) |

7.6 (0.30) |

6.1 (0.24) |

20.8 (0.82) |

38.1 (1.50) |

70.1 (2.76) |

362.7 (14.28) |

| Source: Sistema de Clasificación Bioclimática Mundial[13] | |||||||||||||

People and culture

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1793 | 22,305 | — |

| 1835 | 14,162 | −1.08% |

| 1854 | 35,800 | +5.00% |

| 1900 | 21,886 | −1.06% |

| 1950 | 74,949 | +2.49% |

| 1967 | 137,004 | +3.61% |

| 1992 | 414,307 | +4.53% |

| 2001 | 516,683 | +2.48% |

| 2012 | 630,587 | +1.83% |

| Source: 1793, 1967;[14] 1835;[15] 1854, 1950;[16] 1900;[17] 1992;[18] 2001;[19] 2012[20] | ||

Cochabamba is known as the heart of Bolivia and the gastronomic capital.[21] Traditional cuisine includes: salteñas, chuño, tucumanas, pique macho, silpancho, anticucho, sopa de mani, chicharrón, charke, fricasé, rellenos de papa and many more dishes.[22]

The international street art festival known as the BAU (Bienal de Arte Urbano) has been hosted in Cochabamba every two years since 2011. The festival is organized by proyecto mARTadero, a local cultural center. In 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017 the painting was done in the Villa Coronilla, Geronimo de Osorio neighborhoods. In 2019 the festival focused on the neighborhood Esperanza, on the edge of the Alalay Lake. The festival has featured internationally renowned artists such as Blu (Italy) and Inti (Chile). [23]

Commensurate with other large cities in the Andean highlands of South America, Cochabamba is a city of contrasts. Its central commercial districts, Zona Norte, bounded by Plaza Colón and Plaza 14 de Septiembre, are generally equipped with modern urban amenities and are where the majority of the city's formal business and commercial industries are based. La Cancha, the largest open air market in South America, is also an active place where locals can buy a range of items.[24] An active nightlife is centered around Calle España and along the broad, tree-lined boulevard, El Prado. In contrast, the Zona Sur, a remote area adjacent to the Wilstermann International Airport is visibly impoverished, with adobe homes and unpaved roads, which is often the first impression visitors acquire while commuting into the city.

In 2009, the government under President Evo Morales created a new constitution that declared Spanish and 36 other indigenous languages as the official languages of the country.[25] However, the most widely spoken languages in Cochabamba are Spanish and Quechua. Although the Spanish that is spoken in the Cochabamba region is generally regarded as rather conservative in its phonetics and vocabulary, the use of Quechua terminology (wawa [child] and wistupiku [mouth or twist lips][26]) has been widely incorporated into its standardized form.

As with most cities around the globe, English is increasingly spoken and understood, particularly among business-minded indigenous and repatriated Cochabambinos. English-language instruction has become incorporated into some private schools and universities but is not taught universally, therefore a vast majority of the population does not speak English.

About four-fifths of the population of Bolivia identifies as Catholic.[25]

The city's demographics consist of the following visible groups in order of prevalence: Indigenous (mostly of Quechua and Aymara ethnicity) people, Mestizo, or mixed Indigenous and Spanish European, and people of Spanish (Criollos) and other European descent.

By 2013, the human development index of the Metropolitan region of Cochabamba was 0.801 as a result of a 35% growth in the last 20 years.[27]

Government

Cochabamba, formally the municipality of Cercado, is the capital of Cochabamba department. The city government is divided into executive and legislative branches. The mayor of Cochabamba is the head of the city government, elected by general election for a term of five years. The mayor heads an executive branch, which includes six sub-mayors and a variety of departments comprising 950 functionaries.[28] The 11-member municipal council is the legislative branch.

The current mayor is José María Leyes of the Social Democrat Movement (MDS for its initials in Spanish).

Economy

The area where Cochabamba is situated is commonly referred to as the granary of Bolivia. Its climate is milder than that of the Altiplano region to the west and thus permits extensive agriculture, including grains, potatoes, and coffee in the highlands and sugar cane, cocoa beans, tobacco, and fruit in the Chapare tropical lowlands of the South American Amazon region, an area that had been one of the country's main coca-leaf-producing regions.

Cochabamba is also the industrial hub of Bolivia, producing cars, cleaning products, cosmetics, chemicals, and other items like cement. The economy of Cochabamba is characterized by producing goods and services. Recently, the software industry is becoming increasingly important, with one big company (Jalasoft ) and several small software developers. International companies like GOJA [29] and Assuresoft also have subsidiaries in Cochabamba.[30] Due to this industry growth, Cochabamba is called the "Silicon Valley of Bolivia", with a high demand for professionals immersed in technological careers such as Systems Engineering, Telecommunications and Information Technology.[31]

The airline Boliviana de Aviación has its headquarters in Cochabamba.[32] The defunct airline Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano (LAB Airlines) had its management offices on the grounds of Jorge Wilstermann Airport in Cochabamba.[33][34] In Cochabamba construction has been rapidly increasing in the last couple of years with more than 750 construction sites per year.

Narcotrafic is now controlled in Cochabamba, which used to be related to cocaine dealers several years ago.[35][36][37][38]

Urban transport

The metropolitan area of Cochabamba (Vinto, Tiquipaya, Quillacollo, Colcapirhua, Cochabamba and Sacaba) has an extensive transportation system, which cover all the districts.

There are almost 70 bus and minibus lines, from A to Z, and dozens of minibuses and fixed-route trufis (T.RU.FI, or "taxi con ruta fija") taxi lines. Most lines have GPS system for monitoring and regulation of hour (line 1, line 16, line L, Line 3V, line 20, line 30, etc.). The T.RU.FI service has at least 60 lines; they are identified by signs on the roof of the vehicle showing the route from the initial stop until the final stop, which is also indicated by the line number to which it belongs. The busiest bus lines are:

- Line "Q" (CBBA-QLLO)

- Line "W" (CBBA-QLLO)

- Line "3V"

- Line "B" (Airport)

- Line "K"

- Line "X-10"

- Line "36"

- Line "1"

- Line "30"

- Line "13"

- Line "Z-12" (CBBA-TIQUIPAYA)

And the busiest trufi taxi lines are:

- Taxi Trufi "110"

- Taxi Trufi "260" (Cochabamba-Quillacollo Line)

- Taxi Trufi "270" (Cochabamba-Quillacollo Line)

- Taxi Trufi "103" (Green line and White Line)

- Taxi Trufi "106" (Tiquipaya Line)

- Taxi Trufi "130" (Circular)

- Taxi Trufi "209" (Circular) (Cochabamba-Quillacollo Line)

- Taxi Trufi "123"

- Taxi Trufi "224" (Sacaba Line)

- Taxi Trufi "240" (Sacaba Line)

- Taxi Trufi "244" (Sacaba Line)

- Taxi Trufi "115"

Light Rail

Construction on an interurban light rail network known as Mi Tren linking Cochabamba with Suticollo, El Castillo and San Simon University began in 2017 and is due to be finished in 2020.[39]

Basic services

These companies are nationally recognized:

- Comteco, a company dedicated to the public telephone service to national and district levels, also has Internet service, cable TV, and many others.

- Elfec, the exclusive Cochabamba's electricity distribution company, subsidiary of the state-owned ENDE.

- Semapa, the water distribution and sewerage control company.

- EMSA, the municipal sanitation company, responsible for the pickup, transportation, storage and removed from urban waste produced. EMSA covers 88% of the city and collects 400 tonnes of waste are produced per day.[40] Through the municipal government of Cochabamba, special containers made available throughout the city for the storage of solid waste common. The municipality's sole disposal facility, the K'ara K'ara waste dump (Botadero K'ara K'ara), has been the center of a long-running controversy over pollution of the air and groundwater; it is frequently blockaded by neighboring residents demanding changes.[40]

Media

Cochabamba, as a department with high turnover, have established many media including:

Print media

There are several newspapers in Cochabamba; there is also movement of national and international newspapers, highlighting the following:

- Los Tiempos

- Opinión

- La Voz

- Gente

Radio stations

The main radio stations scattered across the department and the capital are:

- Estrella FM 93,1

- Centro Ltda.

- Mega DJ

- Milenio

- La Voz del Juno

- Kancha Parlaspa

- Bandera Tricolor

- Cochabamba

- Gaviota Dorada

- Del Valle

- San Rafael

- La Voz del Valle - Punata

- Continental

- Oro

- Triunfo Morena

- Epoca

- La Verdad F.M.100.7

- M&D Comunicaciones

- Universal

- Fantástico 97.1

- Panorama FM 90.9

- Punata radio Panorama FM 88.9

- FM-100 Clásica

- FM Stereo 98.7 – La voz de América

- Bethel FFM 95.5

- Ritmo 97.5

- La Triple Nueve 99.9

- La Fabrica de la Musica 107.1

- Magnal de Capinota

- Radios Fides Cochabamba, Punata y Chapare

- CEPRA Pongo Khasa 1,390 AM

- Sonido Lider 95.9 FM Sonido Lider

- Pio XII FM 97.9

- Mundial

- Porvenir

- Radio Cosmos de Bolivia

- CEPRA - Centro de Producción Radiofónica

- CEPRA - Radio Morochota

- Enlace

- Radio HIT 105.7

- Radio Disney Bolivia

Television channels

In the capital and throughout the department there are many television channels that broadcast on a local, provincial, national or international all day or part of it. The transmission towers that transmit channels nationally and internationally are in the high Cala Cala, Villa Moscu or Villa Taquiña.

- Canal 2: Canal 2 Cochabamba Corazón de América (local)

- Canal 4: Red ATB (national)

- Canal 5: Red Bolivisión (national)

- Canal 7: Bolivia TV (Channel of the State)

- Canal 9: Red Uno de Bolivia (national)

- Canal 11: TVU (local)

- Canal 13: Red Unitel (national)

- Canal 15: Cristo Viene la Red (Religious Channel)

- Canal 17: sko TV (local)

- Canal 18: Radio Televisión Popular (RTP) (national)

- Canal 21: Tele C (local)

- Canal 24: Red ADVenir Internacional (Christian Channel/International)

- Canal 26: Metro TV (local)

- Canal 27: Sistema Cristiano de Comunicaciones (local)

- Canal 36: Cadena A (national)

- Canal 39: Univalle TV (local)

- Canal 42: Red PAT (national)

- Canal 48: Red Unitepc (local)

- Canal 51: MTV Cochabamba(local)

- Canal 57: RTL Canal de Noticias(local)

Education

The city is the home of the University of San Simón (UMSS, for "Universidad Mayor de San Simón"), one of the largest and most prominent public universities in Bolivia. UMSS is the second best university in Bolivia according to QS World University Rankings in 2013, but measured by the webmetric scores as the first one during 2013–2017. Among the private universities in Bolivia ranking between the top ten are the Universidad Privada Boliviana (a prestigious business university), Universidad del Valle (strong university in medicine with large enrollment of international students) and Universidad Católica Boliviana "San Pablo". Other well-ranked universities include Escuela Militar de Ingenieria "Antonio Jose de Sucre", Universidad Simón I. Patiño, Universidad de Aquino Bolivia, Universidad Adventista de Bolivia, Universidad Privada Domingo Savio and Universidad Privada Abierta Latinoamericana (UPAL). Cochabamba became the second recipient city of Brazilian students in Bolivia after the city of Santa Cruz, due to the affordable and good living conditions of the city. Also is the home of one of the best schools of Bolivia, Colegio San Agustín

Airport

Cochabamba is served by the modern Jorge Wilstermann International Airport (IATA code CBB), which handles domestic and international flights. It houses the headquarters of Boliviana de Aviación (BOA) Bolivia's national airline and Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano, Bolivia's former national airline. Other domestic airlines that serve the airport include Amaszonas, Ecojet, and Transportes Aéreo Militar.

Neighborhoods

Cochabamba is a steadily emerging market within the Bolivian real estate industry. Since 2010, it became the city with most surface area in construction in Bolivia overpassing Santa Cruz and La Paz. There are many middle and large buildings under construction by 2012. An annual mild climate, abundant greenery, mountain vistas, and a progressive local economy are factors that have contributed to the city's appeal for Bolivian nationals, expatriates and foreigners alike. Historic and affluent neighbourhoods such as Cala Cala, El Mirador, and Lomas de Aranjuez showcase some of the city's most distinguished residences.

- Queru Queru - North

- La Recoleta - North

- Cala Cala - North

- Lomas de Aranjuez - North

- El Mirador - North

- Las Brisas - North

- Sarco - Northwest

- Mayorazgo - Northwest

- Barrio Profesional - Northwest

- America Oeste - Northwest

- Colquiri - Northwest

- Muyurina - Northeast

- Tupuraya - Northeast

- Hippodromo - West

- Villa Busch - West

- Temporal - North

- La Chimba - Southwest

- Aeropuerto - Southwest

- Ticti Norte - Fringe North

- Jaihuayco - South

- Zona sud - South

- Ticti - South

- Valle Hermoso - South

Metropolitan area

Cochabamba is connected with the following towns and cities:

Additional notes of interest

- Cochabamba is also mentioned in the documentary The Corporation, about their fight against privatisation of water by a foreign-owned company, against which the people protested and won. The privatisation had gone to such an extent that even rainwater was not allowed to be collected. Read Cochabamba protests of 2000.

- Cochabamba has been confirmed to be the seat of a future South American Parliament when it is formed by UNASUR. UNASUR has yet to determine what the composition of the Parliament will be, but existing treaties all agree it will meet in Cochabamba.

- Cochabamba was the first place rugby union in Bolivia was formally established.

- Cochabamba was featured as a location in the story in the 1983 film, Scarface. Powerful drug lord Alejandro Sosa resided there, governed large coca plantations and owned cocaine labs where upon further refining, would be shipped to Tony Montana in Florida.

- Cochabamba is the setting of the 2010 movie También la lluvia (Even the rain), which takes place during the water war of 2000. It depicts a crew making a movie about the colonization of Latin America, when the protests against privatization erupt. The film stars Mexican actor Gael García Bernal, and received positive reviews.

- Cochabamba is also the site of several major spammers, as confirmed by the watchdog group Spamhaus.[41]

Migration

Historically, Cochabamba has been a destination for many Bolivians due to relatively improved economic opportunities and a more temperate climate. Former presidents of Bolivia Evo Morales and Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada were both Senators representing Cochabamba, although they were born in Oruro and La Paz respectively and immigrated to Cochabamba at the start of their political careers.

After the road to the eastern city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra was completed in the 1950s, thousands of people from Cochabamba migrated to the lowlands and permanently settled. Many migrants from Cochabamba and their descendants now identify themselves as Cambas after absorbing the regional Bolivian culture of the eastern lowlands, but maintain familiar ties with relatives that remained in Cochabamba.

A large population of Bolivian and Bolivian-descended residents is in the Greater Washington, D.C.-Baltimore–Northern Virginia area of United States (2005 US Census estimates 27,452 +/- 8,883 Bolivians for DC,[42] Virginia,[43] and Maryland[44]); the highest concentration is in Arlington County, Virginia. These figures may represent a census undercount of undocumented Bolivian alien residents. These combined communities have become the centre for recent and established Bolivian immigrants, most of whom are from the department and city of Cochabamba, hence, locally regarded as Little Cochabamba or Arlibamba. Little Cochabamba contains Bolivian-cuisine restaurants and the Escuela Bolivia; a school-within-a-school programme for children and adults. Most of these migrants are Quechua, and come from the municipalities of Tarata, Arbieto, Tolata, Cliza, and Punata. The majority of them first migrated to Argentina before settling in the DC area. https://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/only-bridge-matters-now

A large diaspora of Bolivians occurred when many families had to leave as political exiles persecuted by the political and agrarian reforms instituted by the Movimento Nacional Revolutionario (MNR) starting in 1952. Most migrated to the United States of America, Europe and neighboring South American countries. In the City of San Francisco of Northern California in the United States of America, the Centro Boliviano del Norte de California (Bolivian Center of Northern California) was founded in 1968 as a Non-Profit Organization (ONG) to maintain and develop the Bolivian culture in the USA through the promotion of cultural arts, sports and civic events. https://www.facebook.com/groups/90345332317/ It is the oldest formally established organization of Bolivian immigrants in the USA. An accomplished Bolivian immigrant from Cochabamba of this diaspora was Rosario "Charito" Anaya who was instrumental in establishing in San Francisco the Mission Language and Vocational School (MLVS), a vocational school with its mission of providing vocational training to new immigrants from Latin America. MLVS started at the Centro Social Obrero building in San Francisco (where it currently continues) teaching new immigrants English as a second language and providing secretarial, medical assistant and culinary arts training as well as providing their students employment in banks, hospitals and restaurants. Ms. Anaya was formally recognized as a model citizen by the City of San Francisco.

From the late 1980s to the 1990s, many people from Cochabamba with a low income emigrated to Bergamo, Italy in search of work. Most of the 16,400 (2005 estimate) Bolivians in Bergamo are from Cochabamba which includes both legal and work visa-expired immigrants. This migration is due to the strong relationship between the Roman Catholic Diocese of Bergamo and the Archdiocese of Cochabamba.

Notable residents

- Business people

- Simón Iturri Patiño (1862–1947), mining magnate

- Educators and Intellectuals

- Jaime Escalante, professor and teacher whose life was dramatized in the 1988 film Stand and Deliver

- Renato Prada Oropeza, professor, semiologist, writer

- Musicians & singers

- Edwin Arturo Castellanos Mendoza (b. 1966), musician, artist, politician, Mayor of Cochabamba (2010 - 2015 term)

- Katia Escalera, Soprano

- Gastón Paz Zegarra, (b. 1929). Most regarded Bolivian Opera singer - Baritone

- Jaime Laredo, (b. 1941), classical violinist

- Teófilo Vargas Candia (1866–1961), musician and composer,

[45] author of the Cochabamba Hymn

- Los Kjarkas (since 1965) Cochabambino folk music group, an exemplar of Bolivian traditional music, performers and authors of the famous song "Llorando se Fue", which has been covered internationally

- Literary figures

- Nataniel Aguirre (1843–1888), author.

- Guido Ernesto Cabrerizo (1954), author and poet.

- Adela Zamudio (1874–1925), author and poet, a strong defender of women's rights

- Jesús Lara (1898–1975), author and poet

- Ramon Rocha Monroy (1950-), author, journalist

- Gaby Vallejo Canedo (1941), author, professor of Literature

- Edmundo Paz Soldán - author

- Marcelo Quiroga Santa Cruz (1931–1980), author and prominent politician

- Javier del Granado (1913–1996), poet laureate

- Julia Urquidi (1926-2010), writer, remembered as Mario Vargas Llosa's first wife

- Renato Prada Oropeza (1937–2011), novelist and poet

- Sara Ugarte de Salamanca, poet who had the memorial built to the heroines on 1812

- Óscar Únzaga de la Vega (1916–1959), journalist and historian

- Activists and influential persons

- Klaus Barbie (1913–1991), German SS and Gestapo functionary during the Nazi era.

- Oscar Olivera (1955) Activist, was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2001

Twin towns-Sister cities

Cochabamba has cooperations with:[46]

See also

Notes

- "Ciudades/Comunidades/Centros poblados y Localidades Empadronadas en el Censo de Población y Vivienda 2012". Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia. Archived from the original on 2015-06-12. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha pdf

- Voltaire, Wilson García Mérida,Red. "Huayna Capac, el inca que fundó Cochabamba, por Wilson García Mérida". voltairenet.org. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003), The Incas, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, pp 268-173; La Lone, Mary B. and La Lone, Darrell E. (1987), "The Inca State in the Southern Highlands: State Administrative and Production Enclaves," Ethnohistory, pp. 50-51

- Planet, Lonely. "History of Cochabamba - Lonely Planet Travel Information". www.lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- "For Miners, Increasing Risk on a Mountain at the Heart of Bolivia's Identity". Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- Juan de la Rosa by Nathaniel Aguirre

- Memory of Fire Vol 2: Faces and Masks by Eduardo Galeano p.106

- "FRONTLINE/WORLD . Bolivia - Leasing the Rain . Timeline: Cochabamba Water Revolt | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- de la Fuente, Manuel (2003). "A Personal View: The Water War in Cochabamba, Bolivia: Privatization Triggers an Uprising". Mountain Research and Development. 23 (1): 98–100. doi:10.1659/0276-4741(2003)023[0098:APV]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 3674547.

- "From Water Wars to Water Scarcity: Bolivia's Cautionary Tale". NACLA. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- Forero, Juan. "Who Will Bring Water to the Bolivian Poor?". Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- "Bolivia – Cochabamba". Sistema de Clasificación Bioclimática Mundial. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- "Hitos En La Producción Estadística" [Milestones in Statistical Production] (in Spanish). National Institute of Statistics of Bolivia. 2 November 2011. Archived from the original on 20 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- Zambrana 1986, p. 14

- Mollinedo 1974, p. 58

- Oficina Nacional de Inmigración 1904, p. 145

- "Estadisticas Sociales: Poblacion 1992" [Social Statistics Population 1992] (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia. 2 November 2011. Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2014. Select COCHABAMBA in the Departamento box, CERCADO in the Provincia box, COCHABAMBA (PRIMERA) in the Seccion Muninipal box, and click Ver infomacion to verify data.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2014-01-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.censosbolivia.bo/comunitaria/comunitaria/mpComunitariaVer.aspx?Depto=03&Prov=01&Seccion=01%5B%5D

- "Spanish school Carmen Vega Bolivia". Escuela de español Carmen Vega - Cochabamba- Bolivia. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- Stewart, Harry. "The Best Traditional Foods You Need to Try on Your Trip to Bolivia". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- "Sobre la BAU - About the BAU". BAU. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Moore, Dillon. "La Cancha: An Exuberant Marketplace Experience in Bolivia on Amizade". Amizade. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- "Bolivia - Languages and religion". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- "Wistupiku – Nuestra familia". www.wistupiku.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- https://www.undp.org/content/dam/bolivia/docs/undp_bo_IDH2016.pdf

- Jordán Arandia, Oscar E. (2010-05-30). "Mi compromiso es con Cochabamba". Los Tiempos. Cochabamba. Archived from the original on 2011-09-29. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- https://www.lostiempos.com/oh/actualidad/20180521/raices-bolivianas-goja-mimada-amazoncom

- https://www.assuresoft.com/software-company/contact-us

- http://www.assuresoftcorp.com/blog/growing-demand-engineers-technology

- "Contáctenos Archived 2010-02-08 at the Wayback Machine." Boliviana de Aviación. Retrieved on February 27, 2010.

- "World Airline Directory." Flight International. March 21–27, 2000. 91.

- "Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano's History." Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano. January 9, 2007. Retrieved on February 27, 2010.

- https://www.lostiempos.com/actualidad/pais/20200804/fuerza-antidroga-ejecuta-cinco-operativos-cochabamba-afecta-al-narcotrafico

- https://www.lostiempos.com/actualidad/cochabamba/20200131/fuerza-antidroga-destruye-19-fabricas-cocaina-tropico

- https://www.opinion.com.bo/articulo/policial/felcn-cochabamba-incauta/20200729115212779937.html

- https://www.opinion.com.bo/articulo/policial/felcn-secuestra-mas-32-toneladas-precursores-cochabamba/20200105211924744431.html

- "Empresa ejecutora del tren metropolitano en Cochabamba prevé quitar 18 t de rieles". La Razón. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "Bataderos asfixian a Cochabamba". Los Tiempos. 18 April 2010.

- Spamhaus Blacklist, 2015

- "2005 American Community Survey". US Census Bureau. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- "2005 American Community Survey". US Census Bureau. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- "2005 American Community Survey". US Census Bureau. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- Homenaje de Pentagrama de Recuerdo Archived 2009-03-21 at the Wayback Machine

- "Convenios Internacionales" (official website) (in Spanish). Cochabamba, Bolivia: Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Cochabamba. Archived from the original on 2015-04-04. Retrieved 2015-03-28.

References

- Mollinedo, Arthenio (1974). "Aspectos Generales de la Poblacion Boliviana" [General Aspectos of the Bolivian Population] (PDF) (in Spanish). Bolivian Catholic University—San Pablo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-04. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Oficina Nacional de Inmigración (1904). Censo General de la Población de la República de Bolivia Según el Empadronamiento de 1e. de Septiembre de 1900 [General Census of the Population of the Republic of Bolivia as the Enumeration of September 1st 1900] (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia: JM Gamarra. OCLC 8837699. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- Zambrana, Jorge (1986). La Urbanización de la Ciudad de Cochabamba: Examen Crítico [The Urbanization of the City of Cochabamba: Critical Review] (in Spanish). College of Architects of Bolivia. OCLC 1247798.

External links

- Weather in Cochabamba

- The History of Cochabamba (in Spanish)

- Cbba.info Map of Cochabamba City